supplements

Turmeric is a commonly used herbal product implicated in causing liver injury. The aim of this case series was to describe the clinical, histologic, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) associations of turmeric-associated liver injury enrolled in the U.S. Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN).

was to describe the clinical, histologic, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) associations of turmeric-associated liver injury enrolled in the U.S. Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN).

All adjudicated cases enrolled in DILIN between 2004-2022 in which turmeric was an implicated product were reviewed. Causality was assessed using a 5-point expert opinion score. Available products were analyzed for the presence of turmeric using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography. Genetic analyses included HLA sequencing.

Ten cases of turmeric-associated liver injury were found, all enrolled since 2011 and six since 2017. Of the 10 cases, 8 were women, 9 were White and the median age was 56 years (range, 35-71). Liver injury was hepatocellular in 9 patients and mixed in one. Liver biopsies in 4 patients showed acute hepatitis or mixed cholestatic-hepatitic injury with eosinophils. Five patients were hospitalized, and one patient died of acute liver failure. Chemical analysis confirmed the presence of turmeric in all 7 products tested; 3 also contained piperine (black pepper). HLA typing demonstrated that 7 patients carried HLA-B*35:01, 2 of whom were homozygous, yielding an allele frequency of 0.450 compared to population controls of 0.056-0.069.

The authors concluded that liver injury due to turmeric appears to be increasing in the United States, perhaps reflecting usage patterns or increased combination with black pepper. Turmeric causes potentially severe liver injury that is typically hepatocellular, with a latency of 1 to 4 months and strong linkage to HLA-B*35:01.

Turmeric or curcumin is said to cause multiple effects, such as inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress, tumor cell proliferation, cell death, and infection. Yet, sound clinical trials to test whether these effects might translate into health benefits are rare. In addition, the bioavailability of oral turmeric supplements is known to be low.

Turmeric has been used in food for millennia and is thus generally considered to be safe. Known adverse effects include gastrointestinal problems such as nausea and diarrhea and allergic reactions. Clearly, the new case series casts considerable doubt on the safety of turmeric. Yet, one ought to point out that the number of cases is low (but, on the other hand under-reporting can be assumed to be high). Furthermore, we should take into account that the quality of commercially available products is often low. One must therefore ask whether the liver injuries were truly caused by turmeric itself or by contaminants.

My conclusion is that turmeric is unquestionably an interesting plant with considerable potential as a medicine. At present, there is much hype surrounding it. Yet, hype is almost always contra-productive. If we want to know the true value of turmeric, we need to solve the bioavailability problem and do much more research into its safety and efficacy for defined conditions.

Yesterday, L’EXPRESS published an interview with me. It was introduced with these words (my translation):

Professor emeritus at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, Edzard Ernst is certainly the best connoisseur of unconventional healing practices. For 25 years, he has been sifting through the scientific evaluation of these so-called “alternative” medicines. With a single goal: to provide an objective view, based on solid evidence, of the reality of the benefits and risks of these therapies. While this former homeopathic doctor initially thought he was bringing them a certain legitimacy, he has become one of their most enlightened critics. It is notable as a result of his work that the British health system, the NHS, gave up covering homeopathy. Since then, he has never ceased to alert us to the abuses and lies associated with these practices. For L’Express, he looks back at the challenges of regulating this vast sector and deciphers the main concepts put forward by “wellness” professionals – holism, detox, prevention, strengthening the immune system, etc.

The interview itself is quite extraordinary, in my view. While UK, US, and German journalists usually are at pains to tone down my often outspoken answers, the French journalists (there were two doing the interview with me) did nothing of the sort. This starts with the title of the piece: “Homeopathy is implausible but energy healing takes the biscuit”.

The overall result is one of the most outspoken interviews of my entire career. Let me offer you a few examples (again my translation):

Why are you so critical of celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow who promote these wellness methods?

Sadly, we have gone from evidence-based medicine to celebrity-based medicine. A celebrity without any medical background becomes infatuated with a certain method. They popularize this form of treatment, very often making money from it. The best example of this is Prince Charles, sorry Charles III, who spent forty years of his life promoting very strange things under the guise of defending alternative medicine. He even tried to market a “detox” tincture, based on artichoke and dandelion, which was quickly withdrawn from the market.

How to regulate this sector of wellness and alternative medicines? Today, anyone can present himself as a naturopath or yoga teacher…

Each country has its own regulation, or rather its own lack of regulation. In Germany, for instance, we have the “Heilpraktikter”. Anyone can get this paramedical status, you just have to pass an exam showing that you are not a danger to the public. You can retake this exam as often as you want. Even the dumbest will eventually pass. But these practitioners have an incredible amount of freedom, they even may give infusions and injections. So there is a two-tier health care system, with university-trained doctors and these practitioners.

In France, you have non-medical practitioners who are fighting for recognition. Osteopaths are a good example. They are not officially recognized as a health profession. Many schools have popped up to train them, promising a good income to their students, but today there are too many osteopaths compared to the demand of the patients (knowing that nobody really needs an osteopath to begin with…). Naturopaths are in the same situation.

In Great Britain, osteopaths and chiropractors are regulated by statute. There is even a Royal College dedicated to chiropractic. It’s a bit like having a Royal College for hairdressers! It’s stupid, but we have that. We also have professionals like naturopaths, acupuncturists, or herbalists who have an intermediate status. So it’s a very complex area, depending on the state. It is high time to have more uniform regulations in Europe.

But what would adequate regulation look like?

From my point of view, if you really regulate a profession like homeopaths, it means that these professionals may only practice according to the best scientific evidence available. Which, in practice, means that a homeopath cannot practice homeopathy. This is why these practitioners have a schizophrenic attitude toward regulation. On the one hand, they would like to be recognized to gain credibility. But on the other hand, they know very well that a real regulation would mean that they would have to close shop…

What about the side effects of these practices?

If you ask an alternative practitioner about the risks involved, he or she will take exception. The problem is that there is no system in alternative medicine to monitor side effects and risks. However, there have been cases where chiropractors or acupuncturists have killed people. These cases end up in court, but not in the medical literature. The acupuncturists have no problem saying that a hundred deaths due to acupuncture – a figure that can be found in the scientific literature – is negligible compared to the millions of treatments performed every day in this discipline. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. There are many cases that are not published and therefore not included in the data, because there is no real surveillance system for these disciplines.

Do you see a connection between the wellness sector and conspiracy theories? In the US, we saw that Qanon was thriving in the yoga sector, for example…

Several studies have confirmed these links: people who adhere to conspiracy theories also tend to turn to alternative medicine. If you think about it, alternative medicine is itself a conspiracy theory. It is the idea that conventional medicine, in the name of pharmaceutical interests, in particular, wants to suppress certain treatments, which can therefore only exist in an alternative world. But in reality, the pharmaceutical industry is only too eager to take advantage of this craze for alternative products and well-being. Similarly, universities, hospitals, and other health organizations are all too willing to open their doors to these disciplines, despite the lack of evidence of their effectiveness.

We have repeatedly discussed the issue of detox as used in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and seen that, for a whole range of reasons, it is utter nonsense, e.g.:

- Remember Prince Charles’ ‘Duchy Originals Detox Tincture’?

- Now that you have paid through your nose for the ‘tox’, how about a ‘detox’ through your nose?

- Homotoxicology: ‘the best kept detox secret’? No, it’s even worse than homeopathy!

- Detox is bunk; save your money for something useful, fun or pleasant!

- Scientology detox? No thanks!!!

- ‘DETOX’ = a dangerous and counter-productive illusion

- Have yourself a merry little detox

- It’s beginning to look a lot like DETOX…everywhere I go

But would it not be better to keep toxins from entering the body in the first place?

Yes, you suspected correctly: there are products that claim to do exactly this. Here is a particularly ‘impressive’ one:

ION* Gut Support seals cells in the gut lining, helping to keep toxins out of your body and strengthening the terrain upon which your microbiome can diversify. it uses Humic Extract (from Ancient Soil) and Purified Water.

Humic extract is sourced from ancient soil (roughly 60 million years old), and contains a blend of bacterial metabolites (aka, fulvate) as well as less than 1% of a variety of trace minerals and amino acids including chloride, sodium, lithium, calcium, phosphorus, sulfur, bromide, potassium, iron, antimony, zinc, copper, gold, magnesium, alanine, glycine, histidine, isoleucine, methionine, threonine, and valine.

… the trace minerals in our humic extract are naturally occurring, well below the RDI, and not meant to be used as supplementary to any deficiencies. The truly active compound in humic extract is the fulvate, a unique family of carbon molecules with oxygen-binding sites that are produced by bacteria when they digest nutrients. These molecules are the backbone of the ION* blend, helping with critical functions like cellular and microbial communication and chelation of nutrients.

The science behind ION* lies in strengthening the cellular integrity of your body’s barriers, including not just your gut, but your sinuses and skin as well. Keeping your cells connected keeps these barriers intact, which sets the stage (or “terrain” as we like to call it) for seamless interaction between you and your microbiome.

At ION*, we’re all about connection – starting with the very foundation of our science: tight junction integrity. Tight junctions are the seals between your cells which help to create defensive barriers at the gut, skin, and sinuses. They act intelligently to keep toxins and foreign particles out of the blood stream while also allowing nutrients to enter. These seals are protected by the carbon and mineral metabolites of bacterial digestion.

Unfortunately, tight junction barriers can be degraded with exposure to gluten, glyphosate (the main chemical in commercial herbicides like Roundup), and other environmental insults. ION* has been scientifically shown to promote the strengthening of this barrier through redox signaling, even in the face of those environmental insults.

Your body’s barriers know what to let in (nutrients) and what to ward off (toxins). But the barriers must be strong. ION* works to strengthen your gut, sinus, and skin barriers at a cellular level by fostering tight junction integrity, helping to promote this intelligent defense system at a foundational level.

So much scientific-sounding language can make your head spin.

Which toxins are we talking about?

Are there any clinical studies of the product?

Why is the product so expensive?

What exactly are Humic substances?

I found an answer to only the last question. Humic substances are organic compounds that are important components of humus, the major organic fraction of soil, peat, and coal, and also a constituent of many upland streams, dystrophic lakes, and ocean water.

I imagine that tightening the named junctions – if this is truly a realistic mechanism of action – might interfere with the absorption of all sorts of substances that the body needs for survival. I am, of course, speculating, but one should ask about the risks of using this product (other than the one to the consumer’s bank account).

What we need are clinical studies. And there seem to be none (if anyone knows one, please let me know).

So, what do we call again a health product that makes unsubstantiated claims?

Was it perhaps ‘snake oil’?

The present study was conducted to evaluate the effect of date palm on the sexual function of infertile couples. It was designed as a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted on infertile women and their husbands who referred to infertility clinics in Iran in 2019.

The intervention group was given a palm date capsule and the control group was given a placebo. Data were collected through female sexual function index and International Index of Erectile Function.

The total score of sexual function of females in the intervention group increased significantly from 21.06 ± 2.58 to 27.31 ± 2.59 (P < 0.0001). Also, other areas of sexual function in females (arousal, orgasm, lubrication, pain during intercourse, satisfaction) in the intervention group showed a significant increase compared to females in the control group, which was statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

All areas of male sexual function (erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction and overall satisfaction) significantly increased in the intervention group compared to the control group (P < 0.0001).

The authors concluded that the present study revealed that 1-month consumption of date palm has a positive impact on the sexual function of infertile couples.

In an attempt to explain the rational for this study, the authors state that, since ancient times, date palm has been used in Greece, China and Egypt to treat infertility and increase sexual desire and fertility in females. Rasekh indicated that Palm Pollen is effective in sperm parameters of infertile men. Administering date palm to male rats and measuring the sexual parameters of rats showed an improvement in their sexual function. Studies on animals have shown its effect on the parameters of semen analysis in male animals and increasing hormones.

So, the trial was what might call a ‘long shot’, even a very long one. But that does not render its findings less interesting. If the results could be confirmed, they would certainly have considerable significance.

But can they be confirmed?

I have some doubts.

Two things are remarkable, in my view.

- The study only had subjective endpoints.

- There was as good as no placebo effect in the control group.

How can this be?

One explanation might be that the verum and the placebo capsules were easily identified by their taste of other features. This would then lead to many patients being ‘deblinded’; in other words, the patients on verum would have known and expected to experience an effect, while the patients on placebo would have also known and be disappointed thus not even experiencing a placebo response.

This might be an apt reminder for trialists to include a check of the success of blinding in their list of outcome measures.

Dietary supplements are touted for cognitive protection, but supporting evidence is mixed. COSMOS-Mind tested whether daily administration of cocoa extract (containing 500 mg/day flavanols) versus placebo and a commercial multivitamin-mineral (MVM) versus placebo improved cognition in older women and men.

COSMOS-Mind, a large randomized two-by-two factorial 3-year trial, assessed cognition by telephone at baseline and annually. The primary outcome was a global cognition composite formed from mean standardized (z) scores (relative to baseline) from individual tests, including the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status, Word List and Story Recall, Oral Trail-Making, Verbal Fluency, Number Span, and Digit Ordering. Using intention-to-treat, the primary endpoint was change in this composite with 3 years of cocoa extract use. The pre-specified secondary endpoint was change in the composite with 3 years of MVM supplementation. Treatment effects were also examined for executive function and memory composite scores, and in pre-specified subgroups at higher risk for cognitive decline.

A total of 2262 participants were enrolled (mean age = 73y; 60% women; 89% non-Hispanic White), and 92% completed the baseline and at least one annual assessment. Cocoa extract had no effect on global cognition (mean z-score = 0.03, 95% CI: -0.02 to 0.08; P = .28). Daily MVM supplementation, relative to placebo, resulted in a statistically significant benefit on global cognition (mean z = 0.07, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.12; P = .007), and this effect was most pronounced in participants with a history of cardiovascular disease (no history: 0.06, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.11; history: 0.14, 95% CI -0.02 to 0.31; interaction, nominal P = .01). Multivitamin-mineral benefits were also observed for memory and executive function. The cocoa extract by MVM group interaction was not significant for any of the cognitive composites.

The authors concluded that the Cocoa extract did not benefit cognition. However, COSMOS-Mind provides the first evidence from a large, long-term, pragmatic trial to support the potential efficacy of a MVM to improve cognition in older adults. Additional work is needed to confirm these findings in a more diverse cohort and to identify mechanisms to account for MVM effects.

This trial certainly has a few stunning features. For instance, its sample size was impressive and its follow-up period long. But it also has a few weak points. The study was conducted remotely via mail or telephone which means that compliance was impossible to control. Moreover, the outcome measures were subjective, and blinding was not checked. In addition, I fail to see a plausible mechanism of action. Most importantly, the generalizability of the results to the population at large seems questionable. It might make sense that older individuals many of whom might have low vitamin levels can profit from MVM. Whether this is also true for younger people who are well-nourished might be a different matter.

Developing interventions against age-related memory decline and for older adults experiencing neurodegenerative disease is perhaps one of the greatest challenges of our generation. Spermidine supplementation has shown beneficial effects on brain and cognitive health in animal models, and there has been preliminary evidence of memory improvement in individuals with subjective cognitive decline.

This randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial was aimed at determining the effect of longer-term spermidine supplementation on memory performance and biomarkers in this at-risk group. The study was a monocenter trial carried out at an academic clinical research center in Germany. Eligible individuals were aged 60 to 90 years with subjective cognitive decline who were recruited from health care facilities as well as through advertisements in the general population.

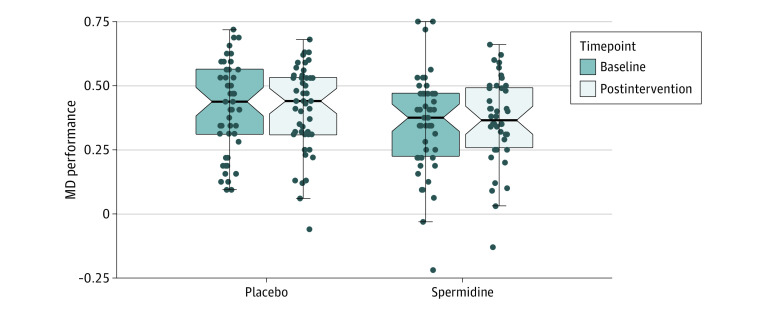

One hundred participants were randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to 12 months of dietary supplementation with either a spermidine-rich dietary supplement extracted from wheat germ (0.9 mg spermidine/d) or placebo (microcrystalline cellulose). Eighty-nine participants (89%) successfully completed the trial. The primary outcome was change in memory performance from baseline to 12-month postintervention assessment (intention-to-treat analysis), operationalized by mnemonic discrimination performance assessed by the Mnemonic Similarity Task. Secondary outcomes included additional neuropsychological, behavioral, and physiological parameters. Safety was assessed in all participants and exploratory per-protocol, as well as subgroup, analyses were performed.

A total of 100 participants (51 in the spermidine group and 49 in the placebo group) were included in the analysis (mean [SD] age, 69 [5] years; 49 female participants [49%]). Over 12 months, no significant changes were observed in mnemonic discrimination performance (between-group difference, -0.03; 95% CI, -0.11 to 0.05; P = .47) and secondary outcomes. Exploratory analyses indicated possible beneficial effects of the intervention on inflammation and verbal memory. Adverse events were balanced between groups.

The authors concluded that in this randomized clinical trial, longer-term spermidine supplementation in participants with subjective cognitive decline did not modify memory and biomarkers compared with placebo. Exploratory analyses indicated possible beneficial effects on verbal memory and inflammation that need to be validated in future studies at higher dosage.

The absence of an effect might have, according to the authors, two reasons.

- The daily dose of 0.9 mg spermidine might not have been sufficient to achieve strong effects on memory function and biomarkers in cognitively healthy older individuals.

- The supplementation with dietary spermidine might not act as a memory booster, but rather prevent age-related memory impairment and development of AD, a possibility supported by evidence from animal studies.

I am tempted to add a third one: spermidine might not be effective at all for this indication (or any other condition)!

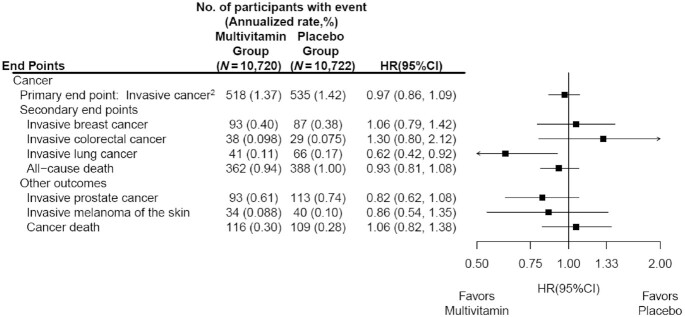

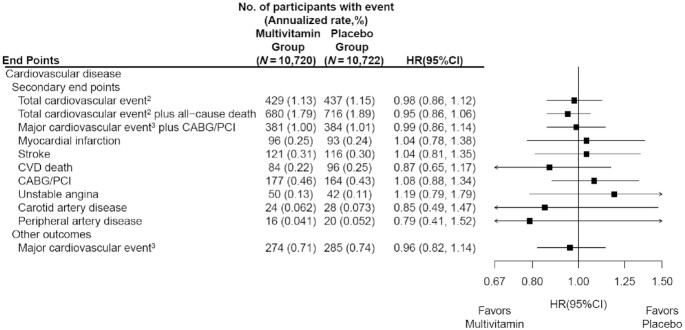

Many older adults commonly take multivitamin-multimineral (MVM) supplements to promote health. Yet, evidence on the use of daily MVMs on invasive cancer is limited.

The objective of this study was therefore to determine if a daily MVM decreases total invasive cancer among older adults. For this purpose, a team of researchers performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2-by-2 factorial trial of a daily MVM and cocoa extract for prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD) among 21,442 US adults (12,666 women aged ≥65 y and 8776 men aged ≥60 y) free of major CVD and recently diagnosed cancer. The intervention phase was from June 2015 through December 2020. This article reports on the MVM intervention.

Participants were randomly assigned to daily MVM or placebo. The primary outcome was total invasive cancer, excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer. Secondary outcomes included major site-specific cancers, total CVD, all-cause mortality, and total cancer risk among those with a baseline history of cancer.

During a median follow-up of 3.6 y, invasive cancer occurred in 518 participants in the MVM group and 535 participants in the placebo group (HR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.86, 1.09; P = 0.57). No significant effect was observed of a daily MVM on breast cancer (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.79, 1.42) or colorectal cancer (HR: 1.30; 95% CI: 0.80, 2.12). The researchers observed a protective effect of a daily MVM on lung cancer (HR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.42, 0.92). The composite CVD outcome occurred in 429 participants in the MVM group and 437 participants in the placebo group (HR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.86, 1.12). MVM use did not significantly affect all-cause mortality (HR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.81, 1.08). There were no safety concerns.

The authors concluded that a daily MVM supplement, compared with placebo, did not significantly reduce the incidence of total cancer among older men and women. Future studies are needed to determine the effects of MVMs on other aging-related outcomes among older adults.

This is an excellent and important study with clear findings. Nevertheless, the authors insist that several limitations should be considered. First, the COSMOS intervention was relatively short to detect a potential small-to-moderate effect on cancer outcomes given the long duration of time typically required for nutritional interventions to potentially reduce cancer risk. Second, the secondary and exploratory analyses should be interpreted with caution, especially given an overall lack of effect of an MVM on the primary outcome of total invasive cancer. Third, the authors successfully leveraged existing cohorts with mass mailings to expedite recruitment and randomization of 21,442 participants into COSMOS. However, generalizability may be limited, with modest diversity of 10% non-Whites and 2.6% Hispanics plus healthy volunteer bias for participants willing and eligible to enroll in a mail-based clinical trial.

Traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine (TCAM) – as most of my readers know, I prefer the abbreviation SCAM for so-called alternative medicine – refers to a broad range of health practices and products typically not part of the ‘conventional medicine’ system. Its use is substantial among the general population. TCAM products and therapies may be used in addition to, or instead of, conventional medicine approaches, and some have been associated with adverse reactions or other harms.

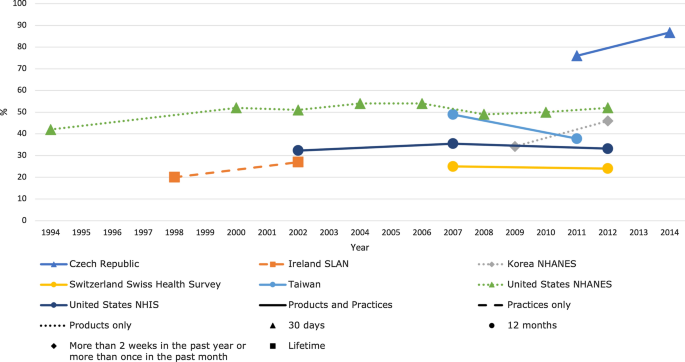

The aims of this systematic review were to identify and examine recently published national studies globally on the prevalence of TCAM use in the general population, to review the research methods used in these studies, and to propose best practices for future studies exploring the prevalence of use of TCAM.

MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and AMED were searched to identify relevant studies published since 2010. Reports describing the prevalence of TCAM use in a national study among the general population were included. The quality of included studies was assessed using a risk of bias tool developed by Hoy et al. Relevant data were extracted and summarised.

Forty studies from 14 countries, comprising 21 national surveys and one cross-national survey, were included. Studies explored the use of TCAM products (e.g. herbal medicines), TCAM practitioners/therapies, or both. Included studies used different TCAM definitions, prevalence time frames and data collection tools, methods and analyses, thereby limiting comparability across studies. The reported prevalence of use of TCAM (products and/or practitioners/therapies) over the previous 12 months was 24–71.3%.

The authors concluded that the reported prevalence of use of TCAM (products and/or practitioners/therapies) is high, but may underestimate use. Published prevalence data varied considerably, at least in part because studies utilise different data collection tools, methods and operational definitions, limiting cross-study comparisons and study reproducibility. For best practice, comprehensive, detailed data on TCAM exposures are needed, and studies should report an operational definition (including the context of TCAM use, products/practices/therapies included and excluded), publish survey questions and describe the data-coding criteria and analysis approach used.

[Trends in prevalence of TCAM use by country for countries with at least two data collection waves from a nationally representative study. For data collected over several years (e.g. 2007–2009), the prevalence data are plotted at the end of the data collection period (e.g. 2009). Solid and perforated lines between consecutive points are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to represent linearity. NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHIS National Health and Interview Survey, SLAN Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition.]

The review discloses that the prevalence reported across countries ranges from 24 to 71%. This huge variability is not very surprising; some of the many reasons for this phenomenon include:

- different TCAM definitions,

- different prevalence time frames,

- different data collection tools,

- different methods of analyzing the data.

Despite these problems, the information summarized in the review is fascinating in several respects. For me, the most interesting message here is this: the plethora of claims that SCAM use is increasing are not supported by sound evidence.

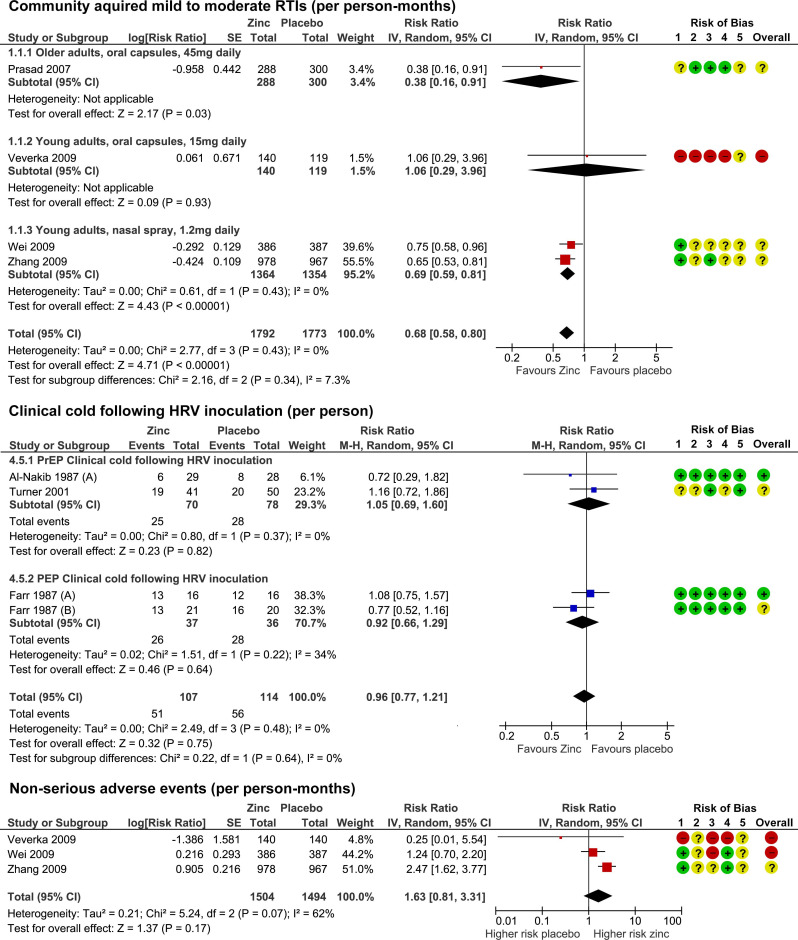

Zinc has been in the limelight recently. The reason is that it has been recommended as a preventative and/or treatment of COVID infections. The basis for such recommendations has been some trial evidence suggesting it is effective for viral respiratory tract infections (RTIs). But the evidence has been full of contradictions which means, we need a systematic review that critically evaluated the totality of the available data.

This systematic review was aimed at evaluating the benefits and risks of zinc formulations compared with controls for the prevention or treatment of acute RTIs in adults.

Seventeen English and Chinese databases were searched in April/May 2020 for randomized clinical trials (RCTs), and from April/May 2020 to August 2020 for SARS-CoV-2 RCTs. Cochrane rapid review methods were applied. Quality appraisals used the Risk of Bias 2.0 and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Twenty-eight RCTs with 5446 participants were identified. None were specific to SARS-CoV-2. Compared with placebo, oral or intranasal zinc prevented 5 RTIs per 100 person-months (95% CI 1 to 8, numbers needed to treat (NNT)=20, moderate-certainty/quality). Sublingual zinc did not prevent clinical colds following human rhinovirus inoculations (relative risk, RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.21, moderate-certainty/quality). On average, symptoms resolved 2 days earlier with sublingual or intranasal zinc compared with placebo (95% CI 0.61 to 3.50, very low-certainty/quality) and 19 more adults per 100 were likely to remain symptomatic on day 7 without zinc (95% CI 2 to 38, NNT=5, low-certainty/quality). There were clinically significant reductions in day 3 symptom severity scores (mean difference, MD -1.20 points, 95% CI -0.66 to -1.74, low-certainty/quality), but not average daily symptom severity scores (standardised MD -0.15, 95% CI -0.43 to 0.13, low-certainty/quality). Non-serious adverse events (AEs) (eg, nausea, mouth/nasal irritation) were higher (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.69, NNHarm=7, moderate-certainty/quality). Compared with active controls, there were no differences in illness duration or AEs (low-certainty/quality). No serious AEs were reported in the 25 RCTs that monitored them (low-certainty/quality).

The authors concluded that in adult populations unlikely to be zinc deficient, there was some evidence suggesting zinc might prevent RTIs symptoms and shorten duration. Non-serious AEs may limit tolerability for some. The comparative efficacy/effectiveness of different zinc formulations and doses were unclear. The GRADE-certainty/quality of the evidence was limited by a high risk of bias, small sample sizes and/or heterogeneity. Further research, including SARS-CoV-2 clinical trials is warranted.

The authors provide a short comment on the assumed mode of action of zinc. The rationale for topical intranasal and sublingual zinc is based on the in vitro effects of zinc ions that can inhibit viral replication, stabilize cell membranes and reduce mucosal inflammation. Other conceivable mechanisms include the activation of T lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes.

The authors also remind us to be cautious: clinicians and consumers need to be aware that considerable uncertainty remains regarding the clinical efficacy of different zinc formulations, doses, and administration routes, and the extent to which efficacy might be influenced by the ever changing epidemiology of the viruses that cause RTIs. The largest body of evidence comes from sublingual lozenges and zinc gluconate and acetate salts, suggesting these are suitable choices. Yet, this does not mean that other administration routes and zinc salts are less effective. The new evidence on the prophylactic effects of low-dose nasal sprays adds weight to the otherwise inconclusive findings from the handful of RCTs evaluating zinc nasal sprays or gels for acute treatment. A minimum therapeutic dose for zinc is also yet to be determined. An earlier review suggested the minimum dose for sublingual lozenges is 75 mg. However, the present analysis does not support this conclusion. Furthermore, a daily oral dose of 15 mg has been shown to upregulate lymphocytes within days, so it is plausible that much lower doses might also be effective.

I had totally forgotten this amusing little episode: According to THE GUARDIAN, Jacob Rees-Mogg (JRM) once tweeted that I should be locked up in the Tower of London!

If you are not from the UK, you may not know this Member of Parliament. So, let me explain.

JRM is the MP for North East Somerset and currently the ‘Minister for Brexit Opportunities and Government Efficiency’. His personal net worth is estimated to be well over £100 million. I probably don’t need to add much more about JRM; there is plenty about him on the Internet and on social media, for instance, this little gem:

Some of JRM’s medically relevant voting records are revealing:

- He voted against raising welfare benefits five times in 2013.

- He voted against higher benefits over long periods for those unable to work as a result of an illness or disability: 14 votes over 5 years.

- Between 2012-2016, he voted 52 times to reduce the spending on welfare benefits.

- He voted to exempt pubs and clubs where food is not served from the smoking ban in October 2010.

- He voted against a law to make private vehicles smoke-free if a child is present.

- He voted against allowing terminally ill people to be given assistance in ending their lives.

Wikipedia mentions that Rees-Mogg is against abortion in all circumstances, stating: “life begins at the point of conception. With same-sex marriage, that is something that people are doing for themselves. With abortion, that is what people are doing to the unborn child.” In September 2017, he expressed “a great sadness” on hearing about how online retailers had reduced pricing of emergency contraception.

In October 2017, it was reported that Somerset Capital Management, of which Rees-Mogg was a partner, had invested £5m in Kalbe Farma, a company that produces and markets misoprostol pills designed to treat stomach ulcers but widely used in illegal abortions in Indonesia. Rees-Mogg defended the investment by arguing that the company in question “obeys Indonesian law so it’s a legitimate investment and there’s no hypocrisy. The law in Indonesia would satisfy the Vatican”. Several days later, it was reported that the same company also held shares in FDC, a company that sold drugs used as part of legal abortions in India. Somerset Capital Management subsequently sold the shares it had held in FDC. Rees-Mogg said: “I am glad to say it’s a stock that we no longer hold. I would not try to defend investing in companies that did things I believe are morally wrong”.

In a nutshell, JRM seems to stand for pretty much everything that I am against. But that is no reason to send me to the Tower of London. So, what exactly was JRM referring to when he wanted me locked up?

The Guardian article explains: At a press conference to mark his retirement [Ernst] agreed with a Daily Mail reporter’s suggestion that the Prince of Wales is a “snake-oil salesman”. In the living room of his house in Suffolk he unpacks the label with the precision on which he prides himself. “He’s a man, he owns a firm that sells this stuff, and I have no qualms at all defending the notion that a tincture of dandelion and artichoke [Duchy Herbals detox remedy] doesn’t do anything to detoxify your body and therefore it is a snake oil.” Far from regretting the choice of words and the controversy it has generated, he appears to relish it.

Looking back at all this bizarre story, I am surprised that JRM did not advocate chopping my head off in the Tower of London. He must have been in a benevolent mood that day!