reviewer bias

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the effectiveness and safety of manual therapy (MT) interventions compared to oral or topical pain medications in the management of neck pain.

The investigators searched from inception to March 2023, in Cochrane Central Register of Controller Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; EBSCO) for randomized controlled trials that examined the effect of manual therapy interventions for neck pain when compared to oral or topical medication in adults with self-reported neck pain, irrespective of radicular findings, specific cause, and associated cervicogenic headaches. Trials with usual care arms were also included if they prescribed medication as part of the usual care and they did not include a manual therapy component. The authors used the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool to assess the potential risk of bias in the included studies, and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) approach to grade the quality of the evidence.

Nine trials with a total of 779 participants were included in the meta-analysis.

- low certainty of evidence was found that MT interventions may be more effective than oral pain medication in pain reduction in the short-term (Standardized Mean Difference: -0.39; 95% CI -0.66 to -0.11; 8 trials, 676 participants),

- moderate certainty of evidence was found that MT interventions may be more effective than oral pain medication in pain reduction in the long-term (Standardized Mean Difference: −0.36; 95% CI −0.55 to −0.17; 6 trials, 567 participants),

- low certainty evidence that the risk of adverse events may be lower for patients who received MT compared to the ones that received oral pain medication (Risk Ratio: 0.59; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.79; 5 trials, 426 participants).

The authors conluded that MT may be more effective for people with neck pain in both short and long-term with a better safety profile regarding adverse events when compared to patients receiving oral pain medications. However, we advise caution when interpreting our safety results due to the different level of reporting strategies in place for MT and medication-induced adverse events. Future MT trials should create and adhere to strict reporting strategies with regards to adverse events to help gain a better understanding on the nature of potential MT-induced adverse events and to ensure patient safety.

Let’s have a look at the primary studies. Here they are with their conclusions (and, where appropriate, my comments in capital letters):

- For participants with acute and subacute neck pain, spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) was more effective than medication in both the short and long term. However, a few instructional sessions of home exercise with (HEA) resulted in similar outcomes at most time points. EXERCISE WAS AS EFFECTIVE AS SMT

- Oral ibuprofen (OI) pharmacologic treatment may reduce pain intensity and disability with respect to neural mobilization (MNNM and CLG) in patients with CP during six weeks. Nevertheless, the non-existence of between-groups ROM differences and possible OI adverse effects should be considered. MEDICATION WAS BETTER THAN MT

- It appears that both treatment strategies (usual care + MT vs usual care) can have equivalent positive influences on headache complaints. Additional studies with larger study populations are needed to draw firm conclusions. Recommendations to increase patient inflow in primary care trials, such as the use of an extended network of participating physicians and of clinical alert software applications, are discussed. MT DOES NOT IMPROVE OUTCOMES

- The consistency of the results provides, in spite of several discussed shortcomings of this pilot study, evidence that in patients with chronic spinal pain syndromes spinal manipulation, if not contraindicated, results in greater improvement than acupuncture and medicine. THIS IS A PILOT STUDY, A TRIAL TESTING FEASIBILITY, NOT EFFECTIVENESS

- The consistency of the results provides, despite some discussed shortcomings of this study, evidence that in patients with chronic spinal pain, manipulation, if not contraindicated, results in greater short-term improvement than acupuncture or medication. However, the data do not strongly support the use of only manipulation, only acupuncture, or only nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for the treatment of chronic spinal pain. The results from this exploratory study need confirmation from future larger studies.

- In daily practice, manual therapy is a favorable treatment option for patients with neck pain compared with physical therapy or continued care by a general practitioner.

- Short-term results (at 7 weeks) have shown that MT speeded recovery compared with GP care and, to a lesser extent, also compared with PT. In the long-term, GP treatment and PT caught up with MT, and differences between the three treatment groups decreased and lost statistical significance at the 13-week and 52-week follow-up. MT IS NOT SUPERIOR [SAME TRIAL AS No 6]

- In this randomized clinical trial, for patients with chronic neck pain, Chuna manual therapy was more effective than usual care in terms of pain and functional recovery at 5 weeks and 1 year after randomization. These results support the need to consider recommending manual therapies as primary care treatments for chronic neck pain.

- In patients with chronic spinal pain syndromes, spinal manipulation, if not contraindicated, may be the only treatment modality of the assessed regimens that provides broad and significant long-term benefit. SAME TRIAL AS No 5

- An impairment-based manual physical therapy and exercise (MTE) program resulted in clinically and statistically significant short- and long-term improvements in pain, disability, and patient-perceived recovery in patients with mechanical neck pain when compared to a program comprising advice, a mobility exercise, and subtherapeutic ultrasound. THIS STUDY DID NOT TEST MT ALONE AND SHOULD NOT HAVE BEEN INCLUDED

I cannot bring myself to characterising this as an overall positive result for MT; anyone who can is guilty of wishful thinking, in my view. The small differences in favor of MT that (some of) the trials report have little to do with the effectiveness of MT itself. They are almost certainly due to the fact that none of these studies were placebo-controlled and double blind (even though this would clearly be possible). In contrast to popping a pill, MT involves extra attention, physical touch, empathy, etc. These factors easily suffice to bring about the small differences that some studies report.

It follows that the main conclusion of the authors of the review should be modified:

There is no compelling evidence to show that MT is more effective for people with neck pain in both short and long-term when compared to patients receiving oral pain medications.

The WHO has just released guidelines for non-surgical management of chronic primary low back pain (CPLBP). The guideline considers 37 types of interventions across five intervention classes. With the guidelines, WHO recommends non-surgical interventions to help people experiencing CPLBP. These interventions include:

- education programs that support knowledge and self-care strategies;

- exercise programs;

- some physical therapies, such as spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and massage;

- psychological therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy; and

- medicines, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines.

The guidelines also outline 14 interventions that are not recommended for most people in most contexts. These interventions should not be routinely offered, as WHO evaluation of the available evidence indicate that potential harms likely outweigh the benefits. WHO advises against interventions such as:

- lumbar braces, belts and/or supports;

- some physical therapies, such as traction;

- and some medicines, such as opioid pain killers, which can be associated with overdose and dependence.

As you probably guessed, I am particularly intrigued by the WHO’s positive recommendation for SMT. Here is what the guideline tells us about this specific topic:

Considering all adults, the guideline development group (GDG) judged overall net benefits [of spinal manipulation] across outcomes to range from trivial to moderate while, for older people the benefit was judged to be largely uncertain given the few trials and uncertainty of evidence in this group. Overall, harms were judged to be trivial to small for all adults and uncertain for older people due to lack of evidence.

The GDG commented that while rare, serious adverse events might occur with SMT, particularly in older people (e.g. fragility fracture in people with bone loss), and highlighted that appropriate training and clinical vigilance concerning potential harms are important. The GDG also acknowledged that rare serious adverse events were unlikely to be detected in trials. Some GDG members considered that the balance of benefits to harms favoured SMT due to small to moderate benefits while others felt the balance did not favour SMT, mainly due to the very low certainty evidence for some of the observed benefits.

The GDG judged the overall certainty of evidence to be very low for all adults, and very low for older people, consistent with the systematic review team’s assessment. The GDG judged that there was likely to be important uncertainty or variability among people with CPLBP with respect to their values and preferences, with GDG members noting that some people might prefer manual

therapies such as SMT, due to its “hands-on” nature, while others might not prefer such an approach.

Based on their experience and the evidence presented from the included trials which offered an average of eight treatment sessions, the GDG judged that SMT was likely to be associated with moderate costs, while acknowledging that such costs and the equity impacts from out-of-pocket costs would vary by setting.

The GDG noted that the cost-effectiveness of SMT might not be favourable when patients do not experience symptom improvements early in the treatment course. The GDG judged that in most settings, delivery of SMT would be feasible, although its acceptability was likely to vary across

health workers and people with CPLBP.

The GDG reached a consensus conditional recommendation in favour of SMT on the basis of small to moderate benefits for critical outcomes, predominantly pain and function, and the likelihood of rare adverse events.

The GDG concluded by consensus that the likely short-term benefits outweighed potential harms, and that delivery was feasible in most settings. The conditional nature of the recommendation was informed by variability in acceptability, possible moderate costs, and concerns that equity might be negatively impacted in a user-pays model of financing.

___________________________

This clearly is not a glowing endorsement or recommendation of SMT. Yet, in my view, it is still too positive. In particular, the assessment of harm is woefully deficient. Looking into the finer details, we find how the GDG assessed harms:

WHO commissioned quantitative systematic evidence syntheses of randomized controlled

trials (RCTs) to evaluate the benefits and harms (as reported in included trials) of each of the

prioritized interventions compared with no care (including trials where the effect of an

intervention could be isolated), placebo or usual care for each of the critical outcomes (refer to Table 2 for the PICO criteria for selecting evidence). Research designs other than RCTs

were not considered.

That explains a lot!

It is not possible to establish the harms of SMT (or any other therapy) on the basis of just a few RCTs, particularly because the RCTs in question often fail to report adverse events. I can be sure of this phenomenon because we investigated it via a systematic review:

Objective: To systematically review the reporting of adverse effects in clinical trials of chiropractic manipulation.

Data sources: Six databases were searched from 2000 to July 2011. Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) were considered, if they tested chiropractic manipulations against any control intervention in human patients suffering from any type of clinical condition. The selection of studies, data extraction, and validation were performed independently by two reviewers.

Results: Sixty RCTs had been published. Twenty-nine RCTs did not mention adverse effects at all. Sixteen RCTs reported that no adverse effects had occurred. Complete information on incidence, severity, duration, frequency and method of reporting of adverse effects was included in only one RCT. Conflicts of interests were not mentioned by the majority of authors.

Conclusions: Adverse effects are poorly reported in recent RCTs of chiropractic manipulations.

The GDG did not cite our review (or any other of our articles on the subject) but, as it was published in a very well-known journal, they must have been aware of it. I am afraid that this wilfull ignorance caused the WHO guideline to underestimate the level of harm of SMT. As there is no post-marketing surveillance system for SMT, a realistic assessment of the harm is far from easy and needs to include a carefully weighted summary of all the published reports (such as this one).

The GDG seems to have been aware of (some of) these problems, yet they ignored them and simply assumed (based on wishful thinking?) that the harms were small or trivial.

Why?

Even the most cursory look at the composition of the GDG, begs the question: could it be that the GDG was highjacked by chiropractors and other experts biased towards SMT?

The more I think of it, the more I feel that this might actually be the case. One committee even listed an expert, Scott Haldeman, as a ‘neurologist’ without disclosing that he foremost is a chiropractor who, for most of his professional life, has promoted SMT in one form or another.

Altogether, the WHO guideline is, in my view, a shameful example of pro-chiropractic bias and an unethical disservice to evidence-based medicine.

When I was still at Exeter, I used to do an average of about 4 peer reviews per week of articles that had been submitted to all sorts of journals for publication. Now I reject most of these invitations and do perhaps just one per month.

Why?

Conducting a peer review is by no means an easy task. You have to realize that the authors have usually put a lot of hard work into their paper and a lot may depend on it in terms of their future. They thus have the right to receive a fair and responsible review. To do the job properly, it took me (even with plenty of experience in reading scientific papers) between 1 and 3 hours per article. Crucially, low-quality articles typically submitted to low-quality journals are more work than papers that adhere to a certain standard.

I do not think that the journal editors who send the submissions out for review appreciate how much work they ask from the reviewers. They normally pay nothing (even if they charge exorbitant handling fees from the authors) and offer you no benefit at all. In addition, many have systems that are more than tedious asking you to register, create a pin number, etc., etc. Then you have to follow certain rules and formats that differ from journal to journal. In a word, they add an administrative burden to the task of reading, understanding, checking a paper, and composing your judgment on it.

All this can be cumbersome but it’s not the reason why I do less and less peer reviews. The true reason is that research papers on so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) are now mostly published in one of the many 3rd class SCAM journals that have recently sprung up. There are so many of them that they, of course, struggle to get enough articles to fill their pages. In turn, this means that they are far too keen to publish anything regardless of its quality or validity. As a consequence, the quality of these articles and their authors are often dismal.

Here is an example of a (rather shocking but not unusual) email I received only today; it might show you what I mean:

Dear Professor!

…

I want to publish some papers in “Areas related to your research field”. Can you help me? I can provide a thank you fee!

For example, I will give you a $2000 thank you fee for helping me write articles. For example, if you add my name to your article, I will give you a $1000 thank you fee. Or I can help you pay for APC.

I know this email is presumptuous, but my friends and I need to publish dozens of papers every year. If you can help me, we can cooperate for a long time. I’m not kidding, I’m very sincere!

If you are offended, please forgive me!

Look forward to your reply!

Warmly Wishes, …

When I do a review for a low-quality SCAM journal and find major defects in an article, my experience has been that the editor then decides to publish it nonetheless. When this happens, I feel frustrated and ask myself: WHY DID THEY ASK FOR MY OPINION IF THEY DO NOT ABIDE BY IT?

Thus I decided that these journals are just as well off without my contributions. So, if you are an editor of a SCAM journal, do me a favor and do not molest me with your invitations to conduct a peer review and

COUNT ME OUT!

Should Acupuncture-Related Therapies be Considered in Prediabetes Control?

No!

If you are pre-diabetic, consult a doctor and follow his/her advice. Do NOT do what acupuncturists or other self-appointed experts tell you. Do NOT become a victim of quackery.

But the authors of a new paper disagree with my view.

So, let’s have a look at the evidence.

Their systematic review was aimed at evaluating the effects and safety of acupuncture-related therapy (AT) interventions on glycemic control for prediabetes. The Chinese researchers searched 14 databases and 5 clinical registry platforms from inception to December 2020. Randomized controlled trials involving AT interventions for managing prediabetes were included.

Of the 855 identified trials, 34 articles were included for qualitative synthesis, 31 of which were included in the final meta-analysis. Compared with usual care, sham intervention, or conventional medicine, AT treatments yielded greater reductions in the primary outcomes, including fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (standard mean difference [SMD] = -0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.06, -0.61; P < .00001), 2-hour plasma glucose (2hPG) (SMD = -0.88; 95% CI, -1.20, -0.57; P < .00001), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (SMD = -0.91; 95% CI, -1.31, -0.51; P < .00001), as well as a greater decline in the secondary outcome, which is the incidence of prediabetes (RR = 1.43; 95% CI, 1.26, 1.63; P < .00001).

The authors concluded that AT is a potential strategy that can contribute to better glycemic control in the management of prediabetes. Because of the substantial clinical heterogeneity, the effect estimates should be interpreted with caution. More research is required for different ethnic groups and long-term effectiveness.

But this is clearly a positive result!

Why do I not believe it?

There are several reasons:

- There is no conceivable mechanism by which AT prevents diabetes.

- The findings heavily rely on Chinese RCTs which are known to be of poor quality and often even fabricated. To trust such research would be a dangerous mistake.

- Many of the primary studies were designed such that they failed to control for non-specific effects of AT. This means that a causal link between AT and the outcome is doubtful.

- The review was published in a 3rd class journal of no impact. Its peer-review system evidently failed.

So, let’s just forget about this rubbish paper?

If only it were so easy!

Journalists always have a keen interest in exotic treatments that contradict established wisdom. Predictably, they have been reporting about the new review thus confusing or misleading the public. One journalist, for instance, stated:

Acupuncture has been used for thousands of years to treat a variety of illnesses — and now it could also help fight one of the 21st century’s biggest health challenges.

New research from Edith Cowan University has found acupuncture therapy may be a useful tool in avoiding type 2 diabetes.

The team of scientists investigated dozens of studies covering the effects of acupuncture on more than 3600 people with prediabetes. This is a condition marked by higher-than-normal blood glucose levels without being high enough to be diagnosed as diabetes.

According to the findings, acupuncture therapy significantly improved key markers, such as fasting plasma glucose, two-hour plasma glucose, and glycated hemoglobin. Additionally, acupuncture therapy resulted in a greater decline in the incidence of prediabetes.

The review can thus serve as a prime example for demonstrating how irresponsible research has the power to mislead millions. This is why I have often said that poor research is a danger to public health.

And what can be done about this more and more prevalent problem?

The answer is easy: people need to behave more responsibly; this includes:

- trialists,

- review authors,

- editors,

- peer-reviewers,

- journalists.

Yes, the answer is easy in theory – but the practice is far from it!

The Lancet is a top medical journal, no doubt. But even such journals can make mistakes, even big ones, as the Wakefield story illustrates. But sometimes, the mistakes are seemingly minor and so well hidden that the casual reader is unlikely to find them. Such mistakes can nevertheless be equally pernicious, as they might propagate untruths or misunderstandings that have far-reaching consequences.

A recent Lancet paper might be an example of this phenomenon. It is entitled “Management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of cancer“, unquestionably an important subject. Its abstract reads as follows:

_______________________

Improvements in early detection and treatment have led to a growing prevalence of survivors of cancer worldwide.

Models of care fail to address adequately the breadth of physical, psychosocial, and supportive care needs of those who survive cancer. In this Series paper, we summarise the evidence around the management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of adult cancers and how to cover these issues in a consultation. Reviewing the patient’s history of cancer and treatments highlights potential long-term or late effects to consider, and recommended surveillance for recurrence. Physical consequences of specific treatments to identify include cardiac dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, lymphoedema, peripheral neuropathy, and osteoporosis. Immunotherapies can cause specific immune-related effects most commonly in the gastrointestinal tract, endocrine system, skin, and liver. Pain should be screened for and requires assessment of potential causes and non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches to management. Common psychosocial issues, for which there are effective psychological therapies, include fear of recurrence, fatigue, altered sleep and cognition, and effects on sex and intimacy, finances, and employment. Review of lifestyle factors including smoking, obesity, and alcohol is necessary to reduce the risk of recurrence and second cancers. Exercise can improve quality of life and might improve cancer survival; it can also contribute to the management of fatigue, pain, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, and cognitive impairment. Using a supportive care screening tool, such as the Distress Thermometer, can identify specific areas of concern and help prioritise areas to cover in a consultation.

_____________________________

You can see nothing wrong? Me neither! We need to dig deeper into the paper to find what concerns me.

In the actual article, the authors state that “there is good evidence of benefit for … acupuncture …”[1]; the same message was conveyed in one of the tables. In support of these categorical statements, the authors quote the current Cochrane review entitled “Acupuncture for cancer pain in adults”. Its abstract reads as follows:

Background: Forty per cent of individuals with early or intermediate stage cancer and 90% with advanced cancer have moderate to severe pain and up to 70% of patients with cancer pain do not receive adequate pain relief. It has been claimed that acupuncture has a role in management of cancer pain and guidelines exist for treatment of cancer pain with acupuncture. This is an updated version of a Cochrane Review published in Issue 1, 2011, on acupuncture for cancer pain in adults.

Objectives: To evaluate efficacy of acupuncture for relief of cancer-related pain in adults.

Search methods: For this update CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, and SPORTDiscus were searched up to July 2015 including non-English language papers.

Selection criteria: Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated any type of invasive acupuncture for pain directly related to cancer in adults aged 18 years or over.

Data collection and analysis: We planned to pool data to provide an overall measure of effect and to calculate the number needed to treat to benefit, but this was not possible due to heterogeneity. Two review authors (CP, OT) independently extracted data adding it to data extraction sheets. Data sheets were compared and discussed with a third review author (MJ) who acted as arbiter. Data analysis was conducted by CP, OT and MJ.

Main results: We included five RCTs (285 participants). Three studies were included in the original review and two more in the update. The authors of the included studies reported benefits of acupuncture in managing pancreatic cancer pain; no difference between real and sham electroacupuncture for pain associated with ovarian cancer; benefits of acupuncture over conventional medication for late stage unspecified cancer; benefits for auricular (ear) acupuncture over placebo for chronic neuropathic pain related to cancer; and no differences between conventional analgesia and acupuncture within the first 10 days of treatment for stomach carcinoma. All studies had a high risk of bias from inadequate sample size and a low risk of bias associated with random sequence generation. Only three studies had low risk of bias associated with incomplete outcome data, while two studies had low risk of bias associated with allocation concealment and one study had low risk of bias associated with inadequate blinding. The heterogeneity of methodologies, cancer populations and techniques used in the included studies precluded pooling of data and therefore meta-analysis was not carried out. A subgroup analysis on acupuncture for cancer-induced bone pain was not conducted because none of the studies made any reference to bone pain. Studies either reported that there were no adverse events as a result of treatment, or did not report adverse events at all.

Authors’ conclusions: There is insufficient evidence to judge whether acupuncture is effective in treating cancer pain in adults.

This conclusion is undoubtedly in stark contrast to the categorical statement of the Lancet authors: “there is good evidence of benefit for … acupuncture …“

What should be done to prevent people from getting misled in this way?

- The Lancet should correct the error. It might be tempting to do this by simply exchanging the term ‘good’ with ‘some’. However, this would still be misleading, as there is some evidence for almost any type of bogus therapy.

- Authors, reviewers, and editors should do their job properly and check the original sources of their quotes.

PS

In case someone argued that the Cochrane review is just one of many, here is the conclusion of an overview of 15 systematic reviews on the subject: The … findings emphasized that acupuncture and related therapies alone did not have clinically significant effects at cancer-related pain reduction as compared with analgesic administration alone.

The state of acupuncture research has long puzzled me. The first thing that would strike who looks at it is its phenomenal increase:

- Until around the year 2000, Medline listed about 200 papers per year on the subject.

- From 2005, there was a steep, near-linear increase.

- It peaked in 2020 when we had a record-breaking 20515 acupuncture papers currently listed in Medline.

Which this amount of research, one would expect to get somewhere. In particular, one would hope to slowly know whether acupuncture works and, if so, for which conditions. But this is not the case.

On the contrary, the acupuncture literature is a complete mess in which it gets more and more difficult to differentiate the reliable from the unreliable, the useful from the redundant, and the truth from the lies. Because of this profound confusion, acupuncture fans are able to claim that their pet-therapy is demonstrably effective for a wide range of conditions, while skeptics insist it is a theatrical placebo. The consumer might listen in bewilderment.

Yesterday (18/1/2021), I had a quick (actually, it was not that quick after all) look into what Medline currently lists in terms of new acupuncture research published in 2021 and found a few other things that are remarkable:

- There were already 100 papers dated 2021 (today, there were even 118); that corresponds to about 5 new articles per day and makes acupuncture one of the most research-active areas of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

- Of these 100 papers, only 7 were clinical trials (CTs). In my view, clinical trials would be more important than any other type of research on acupuncture. To see that they amount to just 7% of the total is therefore disappointing.

- Twelve papers were systematic reviews (SRs). It is odd, I find, to see almost twice the amount of SRs than CTs.

- Eighteen papers referred to protocols of studies of SRs. In particular protocols of SRs are useless in my view. It seems to me that the explanation for this plethora of published protocols might be the fact that Chinese researchers are extremely keen to get papers into Western journals; it is an essential boost to their careers.

- Seven papers were surveys. This multitude of survey research is typical for all types of SCAM.

- Twenty-four articles were on basic research. I find basic research into an ancient therapy of questionable clinical use more than a bit strange.

- The rest of the articles were other types of publications and a few were misclassified.

- The vast majority (n = 81) of the 100 papers were authored exclusively by Chinese researchers (and a few Korean). In view of the fact that it has been shown repeatedly that practically all acupuncture studies from China report positive results and that data fabrication seems rife in China, this dominance of China could be concerning indeed.

Yes, I find all this quite concerning. I feel that we are swamped with plenty of pseudo-research on acupuncture that is of doubtful (in many cases very doubtful) reliability. Eventually, this will create an overall picture for the public that is misleading to the extreme (to check the validity of the original research is a monster task and way beyond what even an interested layperson can do).

And what might be the solution? I am not sure I have one. But for starters, I think, that journal editors should get a lot more discerning when it comes to article submissions from (Chinese) acupuncture researchers. My advice to them and everyone else:

if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is!

The medical literature is currently swamped with reviews of acupuncture (and other forms of TCM) trials originating from China. Here is the latest example (but, trust me, there are hundreds more of the same ilk).

The aim of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of scalp, tongue, and Jin’s 3-needle acupuncture for the improvement of post-apoplectic aphasia. PubMed, Cochrane, Embase databases were searched using index words to identify qualifying randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Meta-analyses of odds ratios (OR) or standardized mean differences (SMD) were performed to evaluate the outcomes between investigational (scalp / tongue / Jin’s 3-needle acupuncture) and control (traditional acupuncture; TA and/or rehabilitation training; RT) groups.

Thirty-two RCTs (1310 participants in investigational group and 1270 in control group) were included. Compared to TA, (OR 3.05 [95% CI: 1.77, 5.28]; p<0.00001), tongue acupuncture (OR 3.49 [1.99, 6.11]; p<0.00001), and Jin’s 3-needle therapy (OR 2.47 [1.10, 5.53]; p = 0.03) had significantly better total effective rate. Compared to RT, scalp acupuncture (OR 4.24 [95% CI: 1.68, 10.74]; p = 0.002) and scalp acupuncture with tongue acupuncture (OR 7.36 [3.33, 16.23]; p<0.00001) had significantly better total effective rate. In comparison with TA/RT, scalp acupuncture, tongue acupuncture, scalp acupuncture with tongue acupuncture, and Jin’s three-needling significantly improved ABC, oral expression, comprehension, writing and reading scores.

The authors concluded that compared to traditional acupuncture and/or rehabilitation training, scalp acupuncture, tongue acupuncture, and Jin’ 3-needle acupuncture can better improve post-apoplectic aphasia as depicted by the total effective rate, the ABC score, and comprehension, oral expression, repetition, denomination, reading and writing scores. However, quality of the included studies was inadequate and therefore further high-quality studies with lager samples and longer follow-up times and with patient outcomes are necessary to verify the results presented herein. In future studies, researchers should also explore the efficacy and differences between scalp acupuncture, tongue acupuncture and Jin’s 3-needling in the treatment of post-apoplectic aphasia.

I’ll be frank: I find it hard to believe that sticking needles in a patient’s tongue restores her ability to speak. What is more, I do not believe a word of this review and its conclusion. And now I better explain why.

- All the primary studies originate from China, and we have often discussed how untrustworthy such studies are.

- All the primary studies were published in Chinese and cannot therefore be checked by most readers of the review.

- The review authors fail to provide the detail about a formal assessment of the rigour of the included studies; they merely state that their methodological quality was low.

- Only 6 of the 32 studies can be retrieved at all via the links provided in the articles.

- As far as I can find out, some studies do not even exist at all.

- Many of the studies compare acupuncture to unproven therapies such as bloodletting.

- Many do not control for placebo effects.

- Not one of the 32 studies reports findings that are remotely convincing.

I conclude that such reviews are little more than pseudo-scientific propaganda. They seem aim at promoting acupuncture in the West and thus serve the interest of the People’s Republic of China. They pollute our medical literature and undermine the trust in science.

I seriously ask myself, are the editors and reviewers all fast asleep?

The journal ‘BMC Complement Altern Med‘ has, in its 18 years of existence, published almost 4 000 Medline-listed papers. They currently charge £1690 for handling one paper. This would amount to about £6.5 million! But BMC are not alone; as I have pointed out repeatedly, EBCAM is arguably even worse.

And this is, in my view, the real scandal. We are being led up the garden path by people who make a very tidy profit doing so. BMC (and EBCAM) must put an end to this nonsense. Alternatively, PubMed should de-list these publications.

This has been going on for far too long; urgent action is required!

Before a scientific paper gets published in a journal, it is submitted to the process of peer-review. Essentially, this means that the editor sends it to 2 or 3 experts in the field asking them to review the submission. Reviewers usually do not get any reward for this, yet the task they are asked to do can be tedious, difficult and time-consuming. Therefore, most reviewers think carefully before accepting it.

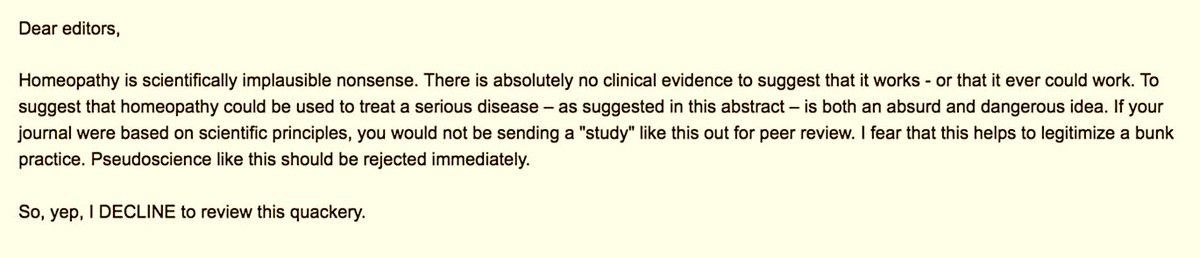

My friend Timothy Caulfield was recently invited by a medical journal to review a study of homeopathy. Here is his response to the editor as posted on Twitter:

I find myself regularly in similar situations. Yet, I have never responded in this way. Here is what I normally do:

- I have a look at the journal itself. If it is one of those SCAM publications, I tend to politely reject the invitation because, in my experience, their review process is farcical and not worth the effort. All too often it has happened that I reviewed a paper that was of very poor quality and thus recommended rejecting it. Yet the editor ignored my expert opinion and published the article nevertheless. This is why, several years ago, I decided enough is enough and no longer consider investing my time is such frustrating work.

- If the journal is of decent standing, I would have a look at the submission the editor sent me. If it makes any sense at all I would consider reviewing it (obviously depending on whether I have the time and the expertise).

- If a decent journal invites me to review a nonsensical paper (I assume that was the case Timothy referred to), I find myself in the same position as my friend Timothy. But, contrary to Timothy, I normally take the trouble to write a critical review of a nonsensical submission. Why? The reason is simple: if I don’t do it, the editor will simply send it to another reviewer. Many journals allow authors to suggest reviewers of their choice. Thus, the editor might send the submission next to the person suggested by the author who most likely will write a favourable review, thus hugely increasing the chances that the paper will be published in a decent journal.

On this blog, we have seen repeatedly that even top journal occasionally publish rubbish papers. Perhaps they do so because well-intentioned experts react in the way my friend Timothy did above (as he failed to tell us what journal invited him, I might be wrong).

If we want pseudoscience to disappear, we are fighting a lost battle. It will always rear its ugly head in third class journals. This is lamentable, but perhaps not so disastrous: by publishing little else than rubbish, these SCAM journals discredit themselves and will eventually be read only by pseudoscientists.

But we can do our bit to get rid of pseudoscience in decent journals. For this to happen, I think, rational thinkers need to accept invitations from such journals and do a proper review. And, of course, they can add to it a sentence or two about the futility of reviewing nonsense.

I am sure Timothy and I both want to eliminate pseudoscience as much as possible. In other words, we are in agreement about the aim, yet we differ in our approach. The question is: which is more effective?

I remember reading this paper entitled ‘Comparison of acupuncture and other drugs for chronic constipation: A network meta-analysis’ when it first came out. I considered discussing it on my blog, but then decided against it for a range of reasons which I shall explain below. The abstract of the original meta-analysis is copied below:

The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and side effects of acupuncture, sham acupuncture and drugs in the treatment of chronic constipation. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of acupuncture and drugs for chronic constipation were comprehensively retrieved from electronic databases (such as PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, CNKI, Wanfang Database, VIP Database and CBM) up to December 2017. Additional references were obtained from review articles. With quality evaluations and data extraction, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was performed using a random-effects model under a frequentist framework. A total of 40 studies (n = 11032) were included: 39 were high-quality studies and 1 was a low-quality study. NMA showed that (1) acupuncture improved the symptoms of chronic constipation more effectively than drugs; (2) the ranking of treatments in terms of efficacy in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome was acupuncture, polyethylene glycol, lactulose, linaclotide, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, prucalopride, sham acupuncture, tegaserod, and placebo; (3) the ranking of side effects were as follows: lactulose, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, polyethylene glycol, prucalopride, linaclotide, placebo and tegaserod; and (4) the most commonly used acupuncture point for chronic constipation was ST25. Acupuncture is more effective than drugs in improving chronic constipation and has the least side effects. In the future, large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to prove this. Sham acupuncture may have curative effects that are greater than the placebo effect. In the future, it is necessary to perform high-quality studies to support this finding. Polyethylene glycol also has acceptable curative effects with fewer side effects than other drugs.

END OF 1st QUOTE

This meta-analysis has now been retracted. Here is what the journal editors have to say about the retraction:

After publication of this article [1], concerns were raised about the scientific validity of the meta-analysis and whether it provided a rigorous and accurate assessment of published clinical studies on the efficacy of acupuncture or drug-based interventions for improving chronic constipation. The PLOS ONE Editors re-assessed the article in collaboration with a member of our Editorial Board and noted several concerns including the following:

- Acupuncture and related terms are not mentioned in the literature search terms, there are no listed inclusion or exclusion criteria related to acupuncture, and the outcome measures were not clearly defined in terms of reproducible clinical measures.

- The study included acupuncture and electroacupuncture studies, though this was not clearly discussed or reported in the Title, Methods, or Results.

- In the “Routine paired meta-analysis” section, both acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups were reported as showing improvement in symptoms compared with placebo. This finding and its implications for the conclusions of the article were not discussed clearly.

- Several included studies did not meet the reported inclusion criteria requiring that studies use adult participants and assess treatments of >2 weeks in duration.

- Data extraction errors were identified by comparing the dataset used in the meta-analysis (S1 Table) with details reported in the original research articles. Errors included aspects of the study design such as the experimental groups included in the study, the number of study arms in the trial, number of participants, and treatment duration. There are also several errors in the Reference list.

- With regard to side effects, 22 out of 40 studies were noted as having reported side effects. It was not made clear whether side effects were assessed as outcome measures for the other 18 studies, i.e. did the authors collect data clarifying that there were no side effects or was this outcome measure not assessed or reported in the original article. Without this clarification the conclusion comparing side effect frequencies is not well supported.

- The network geometry presented in Fig 5 is not correct and misrepresents some of the study designs, for example showing two-arm studies as three-arm studies.

- The overall results of the meta-analysis are strongly reliant on the evidence comparing acupuncture versus lactulose treatment. Several of the trials that assessed this comparison were poorly reported, and the meta-analysis dataset pertaining to these trials contained data extraction errors. Furthermore, potential bias in studies assessing lactulose efficacy in acupuncture trials versus lactulose efficacy in other trials was not sufficiently addressed.

While some of the above issues could be addressed with additional clarifications and corrections to the text, the concerns about study inclusion, the accuracy with which the primary studies’ research designs and data were represented in the meta-analysis, and the reporting quality of included studies directly impact the validity and accuracy of the dataset underlying the meta-analysis. As a consequence, we consider that the overall conclusions of the study are not reliable. In light of these issues, the PLOS ONE Editors retract the article. We apologize that these issues were not adequately addressed during pre-publication peer review.

LZ disagreed with the retraction. YM and XD did not respond.

END OF 2nd QUOTE

Let me start by explaining why I initially decided not to discuss this paper on my blog. Already the first sentence of the abstract put me off, and an entire chorus of alarm-bells started ringing once I read further.

- A meta-analysis is not a ‘study’ in my book, and I am somewhat weary of researchers who employ odd or unprecise language.

- We all know (and I have discussed it repeatedly) that studies of acupuncture frequently fail to report adverse effects (in doing this, their authors violate research ethics!). So, how can it be a credible aim of a meta-analysis to compare side-effects in the absence of adequate reporting?

- The methodology of a network meta-analysis is complex and I know not a lot about it.

- Several things seemed ‘too good to be true’, for instance, the funnel-plot and the overall finding that acupuncture is the best of all therapeutic options.

- Looking at the references, I quickly confirmed my suspicion that most of the primary studies were in Chinese.

In retrospect, I am glad I did not tackle the task of criticising this paper; I would probably have made not nearly such a good job of it as PLOS ONE eventually did. But it was only after someone raised concerns that the paper was re-reviewed and all the defects outlined above came to light.

While some of my concerns listed above may have been trivial, my last point is the one that troubles me a lot. As it also related to dozens of Cochrane reviews which currently come out of China, it is worth our attention, I think. The problem, as I see it, is as follows:

- Chinese (acupuncture, TCM and perhaps also other) trials are almost invariably reporting positive findings, as we have discussed ad nauseam on this blog.

- Data fabrication seems to be rife in China.

- This means that there is good reason to be suspicious of such trials.

- Many of the reviews that currently flood the literature are based predominantly on primary studies published in Chinese.

- Unless one is able to read Chinese, there is no way of evaluating these papers.

- Therefore reviewers of journal submissions tend to rely on what the Chinese review authors write about the primary studies.

- As data fabrication seems to be rife in China, this trust might often not be justified.

- At the same time, Chinese researchers are VERY keen to publish in top Western journals (this is considered a great boost to their career).

- The consequence of all this is that reviews of this nature might be misleading, even if they are published in top journals.

I have been struggling with this problem for many years and have tried my best to alert people to it. However, it does not seem that my efforts had even the slightest success. The stream of such reviews has only increased and is now a true worry (at least for me). My suspicion – and I stress that it is merely that – is that, if one would rigorously re-evaluate these reviews, their majority would need to be retracted just as the above paper. That would mean that hundreds of papers would disappear because they are misleading, a thought that should give everyone interested in reliable evidence sleepless nights!

So, what can be done?

Personally, I now distrust all of these papers, but I admit, that is not a good, constructive solution. It would be better if Journal editors (including, of course, those at the Cochrane Collaboration) would allocate such submissions to reviewers who:

- are demonstrably able to conduct a CRITICAL analysis of the paper in question,

- can read Chinese,

- have no conflicts of interest.

In the case of an acupuncture review, this would narrow it down to perhaps just a handful of experts worldwide. This probably means that my suggestion is simply not feasible.

But what other choice do we have?

One could oblige the authors of all submissions to include full and authorised English translations of non-English articles. I think this might work, but it is, of course, tedious and expensive. In view of the size of the problem (I estimate that there must be around 1 000 reviews out there to which the problem applies), I do not see a better solution.

(I would truly be thankful, if someone had a better one and would tell us)

Did you know that I falsified my qualifications?

Neither did I!

But this is exactly what has been posted on Amazon as a review of my book HOMEOPATHY, THE UNDILUTED FACTS. The Amazon review in question is dated 7 August 2018 and authored by ‘Paul’. As it might not be there for long (because it is clearly abusive) I copied it for you:

Edzard Ernst falsified his qualifications to get a job as a professor. When the university found out they fired him. This book is as false as the Mr Ernst

Over the years, I have received so many insults that I stared to collect them and began to quite like them. I even posted selections on this blog (see for instance here and here). Some are really funny and others are enlightening because they reflect on the mind-set of the authors. All of them show that the author has run out of arguments; thus they really are little tiny victories over unreason, I think.

But, somehow, this new one is different. It is actionable, no doubt, and contains an unusual amount of untruths in so few words.

- I never falsified anything and certainly not my qualification (which is that of a doctor of medicine). If I had, I would be writing these lines from behind bars.

- And if I had done such a thing, I would not have done it ‘to get a job as a professor’ – I had twice been appointed to professorships before I came to the UK (Hannover and Vienna).

- My university did not find out, mainly because there was nothing to find out.

- They did not fire me, but I went into early retirement. Subsequently, they even re-appointed me for several months.

- My book is not false; I don’t even know what a ‘false book’ is (is it a book that is not really a book but something else?).

- And finally, for Paul, I am not Mr Ernst, but Prof Ernst.

I don’t know who Paul is. And I don’t know whether he has even read the book he pretends to be commenting on (from what I see, I think this is very unlikely). I am sure, however, that he did not read my memoir where all these things are explained in full detail. And I certainly do not hope he ever reads it – if he did, he might claim:

This book is as false as the Mr Ernst