menopause

Menopausal symptoms are systemic symptoms that are associated with estrogen deficiency after menopause. Although widely practiced, homeopathy remains under-researched in menopausal syndrome in terms of quality evidence, especially in randomized trials. The efficacy of individualized homeopathic medicines (IHMs) was evaluated in this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the treatment of the menopausal syndrome.

Group 1 (n = 30) received IHMs plus concomitant care, while group 2 (n = 30) had placebos plus concomitant care. The primary outcome measures were the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS) total score and the menopause rating scale (MRS) total score. The secondary endpoint was the Utian quality of life (UQOL) total score. Measurements were taken at baseline and every month up to 3 months.

Intention-to-treat sample (n = 60) was analyzed. Group differences were examined by two-way (split-half) repeated-measure analysis of variance, primarily taking into account all the estimates measured at monthly intervals, and secondarily, by unpaired t-tests comparing the estimates obtained individually every month. The level of significance was set at p < 0.025 two-tailed. Between-group differences were nonsignificant statistically—GCS total score (F1, 58 = 1.372, p = 0.246), MRS total score (F1, 58 = 0.720, p = 0.4), and UQOL total scores (F1, 58 = 2.903, p = 0.094). Some of the subscales preferred IHMs significantly against placebos—for example, MRS somatic subscale (F1, 56 = 0.466, p < 0.001), UQOL occupational subscale (F1, 58 = 4.865, p = 0.031), and UQOL health subscale (F1, 58 = 4.971, p = 0.030). Sulfur and Sepia succus were the most frequently prescribed medicines. No harm or serious adverse events were reported from either group.

The authors concluded that, although the primary analysis failed to demonstrate clearly that the treatment was effective beyond placebo, some significant benefits of IHMs over placebo could still be detected in some of the subscales in the secondary analysis.

The article was published in the recently re-named JICM, a journal that, when it was still called JCAM, featured regularly on this blog. As such, the paper is remarkable: who would have thought that this journal might publish a trial of homeopathy with a squarely negative result?

Yes, I know, the surprise is tempered by the fact that the authors make much in the conclusions of their article about the significant findings related to secondary analyses. Should we tell them that these results are all but irrelevant?

Better not!

Menopausal symptoms are a domaine of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), not least because many women are worried about hormone treatments and therefore want ‘something natural’. TCM practitioners are only too keen to offer their services. But do their treatments really work?

This study aimed to analyze the effectiveness of acupuncture combined with Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) on mood disorder symptoms for menopausal women.

A total of 95 qualified Chinese participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups:

- 31 in the acupuncture combined with CHM group (combined group),

- 32 in the acupuncture combined with CHM placebo group (acupuncture group),

- 32 in the CHM combined with sham acupuncture group (CHM group).

The patients were treated for 8 weeks and followed up for 4 weeks. The data were collected using the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS), self-rating depression scale (SDS), self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), and safety index.

The three groups each showed significant decreases in the GCS, SDS, and SAS after treatment (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the effect on the GCS total score and the anxiety domain lasted until the follow-up period in the combined group (p < 0.05). Within the three groups, there was no difference in GCS and SAS between the three groups after treatment (p > 0.05). However, the combined group showed significant improvement in the SDS, compared with both the acupuncture group and the CHM group at 8 weeks and 12 weeks (p < 0.05). No obvious abnormal cases were found in any of the safety indexes.

The authors concluded that the results suggest that either acupuncture, or CHM or combined therapy offer safe improvement of mood disorder symptoms for menopausal women. However, the combination therapy was associated with more stable effects in the follow-up period and a superior effect on improving depression symptoms.

Previous reviews have drawn conclusions that are far less positive, e.g.:

- the observed clinical benefit associated with acupuncture may be due, in part, or in whole to nonspecific effects.

- the evidence gathered was not sufficient to affirm the effectiveness of traditional acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture.

- For natural menopause, one large study has shown acupuncture to be superior to self-care alone in reducing the number of hot flushes and improving the quality of life; five small studies have been unable to demonstrate that the effect of acupuncture is limited to any particular points, as traditional theory would suggest; and one study showed acupuncture was superior to blunt needle for flash frequency but not intensity.

- Sham-controlled RCTs fail to show specific effects of acupuncture for control of menopausal hot flushes.

It seems therefore wise to take the conclusions of the new study with a pinch of salt. The intergroup difference observed in this trial may well be due to residual biases, multiple testing, or coincidence. And the reported intragroup differences are in complete accord with the fact that the employed therapies are mere placebos.

This, of course, begs the question of whether SCAM has anything else to offer for women suffering from menopausal symptoms. To answer it, I can refer you to one of our systematic reviews:

Some evidence exists in favour of phytosterols and phytostanols for diminishing LDL and total cholesterol in postmenopausal women. Similarly, regular fiber intake is effective in reducing serum total cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women. Clinical evidence also exists on the effectiveness of vitamin K, a combination of calcium and vitamin D or a combination of walking with other weight-bearing exercise in reducing bone mineral density loss and the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal women. Black cohosh appears to be effective therapy for relieving menopausal symptoms, primarily hot flashes, in early menopause. Phytoestrogen extracts, including isoflavones and lignans, appear to have only minimal effect on hot flashes but have other positive health effects, e.g. on plasma lipid levels and bone loss. For other commonly used CAMs, e.g. probiotics, prebiotics, acupuncture, homeopathy and DHEA-S, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are scarce and the evidence is unconvincing. More and better RCTs testing the effectiveness of these treatments are needed.

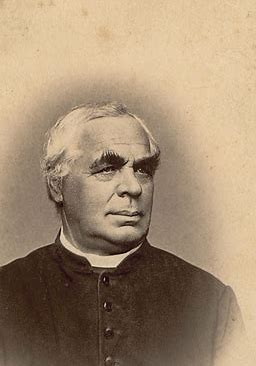

Kneipp therapy goes back to Sebastian Kneipp (1821-1897), a catholic priest who was convinced to have cured himself of tuberculosis by using various hydrotherapies. Kneipp is often considered by many to be ‘the father of naturopathy’. Kneipp therapy consists of hydrotherapy, exercise therapy, nutritional therapy, phototherapy, and ‘order’ therapy (or balance). Kneipp therapy remains popular in Germany where whole spa towns live off this concept.

The obvious question is: does Kneipp therapy work? A team of German investigators has tried to answer it. For this purpose, they conducted a systematic review to evaluate the available evidence on the effect of Kneipp therapy.

A total of 25 sources, including 14 controlled studies (13 of which were randomized), were included. The authors considered almost any type of study, regardless of whether it was a published or unpublished, a controlled or uncontrolled trial. According to EPHPP-QAT, 3 studies were rated as “strong,” 13 as “moderate” and 9 as “weak.” Nine (64%) of the controlled studies reported significant improvements after Kneipp therapy in a between-group comparison in the following conditions:

- chronic venous insufficiency,

- hypertension,

- mild heart failure,

- menopausal complaints,

- sleep disorders in different patient collectives,

- as well as improved immune parameters in healthy subjects.

No significant effects were found in:

- depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients with climacteric complaints,

- quality of life in post-polio syndrome,

- disease-related polyneuropathic complaints,

- the incidence of cold episodes in children.

Eleven uncontrolled studies reported improvements in allergic symptoms, dyspepsia, quality of life, heart rate variability, infections, hypertension, well-being, pain, and polyneuropathic complaints.

The authors concluded that Kneipp therapy seems to be beneficial for numerous symptoms in different patient groups. Future studies should pay even more attention to methodologically careful study planning (control groups, randomisation, adequate case numbers, blinding) to counteract bias.

On the one hand, I applaud the authors. Considering the popularity of Kneipp therapy in Germany, such a review was long overdue. On the other hand, I am somewhat concerned about their conclusions. In my view, they are far too positive:

- almost all studies had significant flaws which means their findings are less than reliable;

- for most indications, there are only one or two studies, and it seems unwarranted to claim that Kneipp therapy is beneficial for numerous symptoms on the basis of such scarce evidence.

My conclusion would therefore be quite different:

Despite its long history and considerable popularity, Kneipp therapy is not supported by enough sound evidence for issuing positive recommendations for its use in any health condition.

Acupuncture is all over the news today. The reason is a study just out in BMJ-Open.

The aim of this new RCT was to investigate the efficacy of a standardised brief acupuncture approach for women with moderate-tosevere menopausal symptoms. Nine Danish primary care practices recruited 70 women with moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms. Nine general practitioners with accredited education in acupuncture administered the treatments.

The acupuncture style was western medical with a standardised approach in the pre-defined acupuncture points CV-3, CV-4, LR-8, SP-6 and SP-9. The intervention group received one treatment for five consecutive weeks. The control group received no acupuncture but was offered treatment after 6 weeks. Outcomes were the differences between the two groups in changes to mean scores using the scales in the MenoScores Questionnaire, measured from baseline to week 6. The primary outcome was the hot flushes scale; the secondary outcomes were the other scales in the questionnaire. All analyses were based on intention-to-treat analysis.

Thirty-six patients received the intervention, and 34 were in the control group. Four participants dropped out before week 6. The acupuncture intervention significantly decreased hot flushes, day-and-night sweats, general sweating, menopausal-specific sleeping problems, emotional symptoms, physical symptoms and skin and hair symptoms compared with the control group at the 6-week follow-up. The pattern of decrease in hot flushes, emotional symptoms, skin and hair symptoms was already apparent three weeks into the study. Mild potential adverse effects were reported by four participants, but no severe adverse effects were reported.

The authors concluded that the standardised and brief acupuncture treatment produced a fast and clinically relevant reduction in moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms during the six-week intervention.

The only thing that I find amazing here is the fact the a reputable journal published such a flawed trial arriving at such misleading conclusions.

- The authors call it a ‘pragmatic’ trial. Yet it excluded far too many patients to realistically qualify for this characterisation.

- The trial had no adequate control group, i.e. one that can account for placebo effects. Thus the observed outcomes are entirely in keeping with the powerful placebo effect that acupuncture undeniably has.

- The authors nevertheless conclude that ‘acupuncture treatment produced a fast and clinically relevant reduction’ of symptoms.

- They also state that they used this design because no validated sham acupuncture method exists. This is demonstrably wrong.

- In my view, such misleading statements might even amount to scientific misconduct.

So, what would be the result of a trial that is rigorous and does adequately control for placebo-effects? Luckily, we do not need to rely on speculation here; we have a study to demonstrate the result:

Background: Hot flashes (HFs) affect up to 75% of menopausal women and pose a considerable health and financial burden. Evidence of acupuncture efficacy as an HF treatment is conflicting.

Objective: To assess the efficacy of Chinese medicine acupuncture against sham acupuncture for menopausal HFs.

Design: Stratified, blind (participants, outcome assessors, and investigators, but not treating acupuncturists), parallel, randomized, sham-controlled trial with equal allocation. (Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12611000393954)

Setting: Community in Australia.

Participants: Women older than 40 years in the late menopausal transition or postmenopause with at least 7 moderate HFs daily, meeting criteria for Chinese medicine diagnosis of kidney yin deficiency.

Interventions:10 treatments over 8 weeks of either standardized Chinese medicine needle acupuncture designed to treat kidney yin deficiency or noninsertive sham acupuncture.

Measurements: The primary outcome was HF score at the end of treatment. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, anxiety, depression, and adverse events. Participants were assessed at 4 weeks, the end of treatment, and then 3 and 6 months after the end of treatment. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted with linear mixed-effects models.

Results: 327 women were randomly assigned to acupuncture (n = 163) or sham acupuncture (n = 164). At the end of treatment, 16% of participants in the acupuncture group and 13% in the sham group were lost to follow-up. Mean HF scores at the end of treatment were 15.36 in the acupuncture group and 15.04 in the sham group (mean difference, 0.33 [95% CI, −1.87 to 2.52]; P = 0.77). No serious adverse events were reported.

Limitation: Participants were predominantly Caucasian and did not have breast cancer or surgical menopause.

Conclusion: Chinese medicine acupuncture was not superior to noninsertive sham acupuncture for women with moderately severe menopausal HFs.

My conclusion from all this is simple: acupuncture trials generate positive findings, provided the researchers fail to test it rigorously.

Endocrine therapy (ET) is often used to reduce the risk of recurrence in hormone receptor-expressing disease. It is associated with worsening of climacteric symptoms can therefore have a negative impact on the quality of life (QoL) of those affected. Homeopathy is sometimes recommended for management of hot flushes (HF), and a new study aimed to test whether it is effective.

In this multi-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT, women were included suffering from histologically proven non-metastatic localized breast cancer, with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-Performance Status (ECOG-PS) ≤ 1, treated for at least 1 month with adjuvant ET, and complaining about moderate to severe HF. Patients scheduled for chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, or those with associated pathology known to induce HF were excluded. After a 2- to 4-week placebo administration, patients were randomly assigned to receiving the homeopathic medicine complex Actheane® (arm A) or placebo (arm P). Randomization was stratified by adjuvant ET (taxoxifen/aromatase inhibitor) and recruiting site. HF scores (HFS) were calculated as the mean of HF frequencies before randomization, at 4, and at 8 weeks post-randomization (pre-, 4w,- and 8w-) weighted by a 4-level intensity scale. The primary endpoint was the variation between pre- and 4week-HFS. Secondary endpoints included HFS variation between pre- and 8week-HFS. Compliance and tolerance were assessed 8 weeks after randomization, and QoL and satisfaction were assessed at 4- and 8-week post-randomization.

In total, 138 patients were randomized (A, 65; P, 73). Median 4week-HFS absolute variation (A, - 2.9; P, - 2.5 points, p = 0.756) and relative decrease (A, - 17%; P, - 15%, p = 0.629) were not statistically different between the two arms. However, 4week-HFS decreased for 46 (75%) in A vs 48 (68%) patients in P arm. 4week-QoL was stable or improved for respectively 43 (72%) vs 51 (74%) patients (p = 0.470).

The authors concluded that the efficacy endpoint was not reached, and BRN-01 administration was not demonstrated as an efficient treatment to alleviate HF symptoms due to adjuvant ET in breast cancer patients. However, the study drug administration led to decreased HFS with a positive impact on QoL. Without any recommended treatment to treat or alleviate the HF-related disabling symptoms, Actheane® could be a promising option, providing an interesting support for better adherence to ET, thereby reducing the risk of recurrence with a good tolerance profile.

At the start of their abstract, the authors state that homeopathy might allow a better management of hot flushes (HF). Frankly, I fail to see the evidence for this statement. The only study I know of (by a known advocate of homeopathy) showed no effect of homeopathy.

Acthéane is a mixture marketed by Boiron of 5 ingredients:

– Actaea racemosa 4 CH : 0,5 mg

– Arnica montana 4 CH : 0,5 mg

– Glonoinum 4 CH : 0,5 mg

– Lachesis mutus 5 CH : 0,5 mg

– Sanguinaria canadensis 4 CH : 0,5 mg

I am not aware of evidence that this remedy might work.

If there is no plausible rationale for conducting a study, does that not mean it is ethically questionable to do it?

Apart from that, the study seems well-designed. It is not very well presented, but the paper is clear enough. Its results are as one would expect from a rigorous trial of homeopathy. The fact that the authors try to squeeze out some positive messages from this squarely negative study is, of course, pathetic. To mention in the abstract that 4week-HFS decreased for 46 (75%) in A vs 48 (68%) patients (not the primary outcome measure) in P arm is little more than an embarrassing tribute to the sponsor, in my view.

Boiron Canada state on their website that Acteane® is a homeopathic medicine used for the relief of perimenopause and menopause symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, sleep disorders, headache, irritability and mood swings.

The benefits of Acteane, a new solution for women:

The benefits of Acteane, a new solution for women:

• Hormone-free

• Soy-free

• Can be associated with other treatments used during perimenopause

• Non-drowsy

• Chewable tablets

• Does not require water

WILL THEY NOW ADD ‘EFFECT-FREE’ TO THEIR LIST?

The only time we discussed gua sha, it led to one of the most prolonged discussions we ever had on this blog (536 comments so far). It seems to be a topic that excites many. But what precisely is it?

The only time we discussed gua sha, it led to one of the most prolonged discussions we ever had on this blog (536 comments so far). It seems to be a topic that excites many. But what precisely is it?

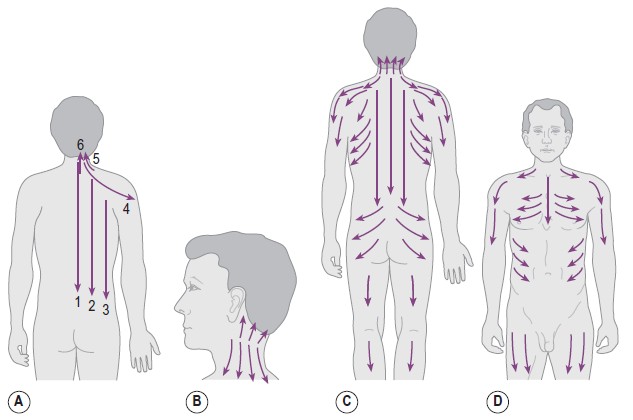

Gua sha, sometimes referred to as “scraping”, “spooning” or “coining”, is a traditional Chinese treatment that has spread to several other Asian countries. It has long been popular in Vietnam and is now also becoming well-known in the West. The treatment consists of scraping the skin with a smooth edge placed against the pre-oiled skin surface, pressed down firmly, and then moved downwards along muscles or meridians. According to its proponents, gua sha stimulates the flow of the vital energy ‘chi’ and releases unhealthy bodily matter from blood stasis within sore, tired, stiff or injured muscle areas.

The technique is practised by TCM practitioners, acupuncturists, massage therapists, physical therapists, physicians and nurses. Practitioners claim that it stimulates blood flow to the treated areas, thus promoting cell metabolism, regeneration and healing. They also assume that it has anti-inflammatory effects and stimulates the immune system.

These effects are said to last for days or weeks after a single treatment. The treatment causes microvascular injuries which are visible as subcutaneous bleeding and redness. Gua sha practitioners make far-reaching therapeutic claims, including that the therapy alleviates pain, prevents infections, treats asthma, detoxifies the body, cures liver problems, reduces stress, and contributes to overall health.

Gua sha is mildly painful, almost invariably leads to unsightly blemishes on the skin which occasionally can become infected and might even be mistaken for physical abuse.

There is little research of gua sha, and the few trials that exist tend to be published in Chinese. But recently, a new paper has emerged that is written in English. The goal of this systematic review was to evaluate the available evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of gua sha for the treatment of patients with perimenopausal syndrome.

A total of 6 RCTs met the inclusion criteria. Most were of low methodological quality. When compared with Western medicine therapy alone, meta-analysis of 5 RCTs indicated favorable statistically significant effects of gua sha plus Western medicine. Moreover, study participants who received Gua Sha therapy plus Western medicine therapy showed significantly greater improvements in serum levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) compared to participants in the Western medicine therapy group.

The authors concluded that preliminary evidence supported the hypothesis that Gua Sha therapy effectively improved the treatment efficacy in patients with perimenopausal syndrome. Additional studies will be required to elucidate optimal frequency and dosage of Gua Sha.

This sounds as though gua sha is a reasonable therapy.

Yet, I think this notion is worth being critically analysed. Here are some caveats that spring into my mind:

- Gua sha lacks biological plausibility.

- The reviewed trials are too flawed to allow any firm conclusions.

- As most are published in Chinese, non-Chinese speakers have no possibility to evaluate them.

- The studies originate from China where close to 100% of TCM trials report positive results.

- In my view, this means they are less than trustworthy.

- The authors of the above-cited review are all from China and might not be willing, able or allowed to publish a critical paper on this subject.

- The review was published in Complement Ther Clin Pract., a journal not known for its high scientific standards or critical stance towards TCM.

So, is gua sha a reasonable therapy?

I let you make this judgement.

Acupuncture for hot flushes?

What next?

I know, to rational thinkers this sounds bizarre – but, actually, there are quite a few studies on the subject. Enough evidence for me to have published not one but four different systematic reviews on the subject.

The first (2009) concluded that “the evidence is not convincing to suggest acupuncture is an effective treatment of hot flash in patients with breast cancer. Further research is required to investigate whether there are specific effects of acupuncture for treating hot flash in patients with breast cancer.”

The second (also 2009) concluded that “sham-controlled RCTs fail to show specific effects of acupuncture for control of menopausal hot flushes. More rigorous research seems warranted.”

The third (again 2009) concluded that “the evidence is not convincing to suggest acupuncture is an effective treatment for hot flush in patients with prostate cancer. Further research is required to investigate whether acupuncture has hot-flush-specific effects.”

The fourth (2013), a Cochrane review, “found insufficient evidence to determine whether acupuncture is effective for controlling menopausal vasomotor symptoms. When we compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture, there was no evidence of a significant difference in their effect on menopausal vasomotor symptoms. When we compared acupuncture with no treatment there appeared to be a benefit from acupuncture, but acupuncture appeared to be less effective than HT. These findings should be treated with great caution as the evidence was low or very low quality and the studies comparing acupuncture versus no treatment or HT were not controlled with sham acupuncture or placebo HT. Data on adverse effects were lacking.”

And now, there is a new systematic review; its aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture for treatment of hot flash in women with breast cancer. The searches identified 12 relevant articles for inclusion. The meta-analysis without any subgroup or moderator failed to show favorable effects of acupuncture on reducing the frequency of hot flashes after intervention (n = 680, SMD = − 0.478, 95 % CI −0.397 to 0.241, P = 0.632) but exhibited marked heterogeneity of the results (Q value = 83.200, P = 0.000, I^2 = 83.17, τ^2 = 0.310). The authors concluded that “the meta-analysis used had contradictory results and yielded no convincing evidence to suggest that acupuncture was an effective treatment of hot flash in patients with breast cancer. Multi-central studies including large sample size are required to investigate the efficiency of acupuncture for treating hot flash in patients with breast cancer.”

What follows from all this?

- The collective evidence does NOT seem to suggest that acupuncture is a promising treatment for hot flushes of any aetiology.

- The new paper is unimpressive, in my view. I don’t see the necessity for it, particularly as it fails to include a formal assessment of the methodological quality of the primary studies (contrary to what the authors state in the abstract) and because it merely includes articles published in English (with a therapy like acupuncture, such a strategy seems ridiculous, in my view).

- I predict that future studies will suggest an effect – as long as they are designed such that they are open to bias.

- Rigorous trials are likely to show an effect beyond placebo.

- My own reviews typically state that MORE RESEARCH IS NEEDED. I regret such statements and would today no longer issue them.

Yes, we discussed this study on a previous blog post. But, as it is ‘ACUPUNCTURE AWARENESS WEEK’ in the UK, and because of another reason (which will become clear in a minute) I decided to revisit the trial.

In case you have forgotten, here is its abstract once again:

Background: Hot flashes (HFs) affect up to 75% of menopausal women and pose a considerable health and financial burden. Evidence of acupuncture efficacy as an HF treatment is conflicting.

Objective: To assess the efficacy of Chinese medicine acupuncture against sham acupuncture for menopausal HFs.

Design: Stratified, blind (participants, outcome assessors, and investigators, but not treating acupuncturists), parallel, randomized, sham-controlled trial with equal allocation. (Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12611000393954)

Setting: Community in Australia.

Participants: Women older than 40 years in the late menopausal transition or postmenopause with at least 7 moderate HFs daily, meeting criteria for Chinese medicine diagnosis of kidney yin deficiency.

Interventions: 10 treatments over 8 weeks of either standardized Chinese medicine needle acupuncture designed to treat kidney yin deficiency or noninsertive sham acupuncture.

Measurements: The primary outcome was HF score at the end of treatment. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, anxiety, depression, and adverse events. Participants were assessed at 4 weeks, the end of treatment, and then 3 and 6 months after the end of treatment. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted with linear mixed-effects models.

Results: 327 women were randomly assigned to acupuncture (n = 163) or sham acupuncture (n = 164). At the end of treatment, 16% of participants in the acupuncture group and 13% in the sham group were lost to follow-up. Mean HF scores at the end of treatment were 15.36 in the acupuncture group and 15.04 in the sham group (mean difference, 0.33 [95% CI, −1.87 to 2.52]; P = 0.77). No serious adverse events were reported.

Limitation: Participants were predominantly Caucasian and did not have breast cancer or surgical menopause.

Conclusion: Chinese medicine acupuncture was not superior to noninsertive sham acupuncture for women with moderately severe menopausal HFs.

When I first discussed this trial, I commented that the trial has several strengths: it includes a large sample size and the patients were adequately blinded to eliminate the effects of expectations. It was published in a top journal, and we can therefore assume that it was properly peer-reviewed. Combined with the evidence from our previous systematic review, this indicates that acupuncture has no effect beyond placebo.

The reason for bringing it up again is that a comment about the study has recently appeared, not just any old comment but one from the British Medical Acupuncture Society. It is, in my view, gratifying and interesting. It was published on ‘facebook’ and is therefore in danger of getting forgotten. I hope to preserve it by citing it in full.

Here it is:

A large rigorous trial published in a prestigious general medical journal, and the usual mantra rings out – acupuncture is no better than sham. In this case there was not a fraction of difference from a non-penetrating sham in a two-armed trial with over 300 women. Ok,…so we have known for some time that we really need 400 in each arm to demonstrate the usual difference over sham seen in meta-analysis in pain conditions, but there really was not even a sniff of a difference here. So is that it for acupuncture in hot flushes? Well, we have a 40% symptom reduction in both groups, and a strong conviction from some practitioners that it really seems to work. Is 40% enough for a strong conviction? I have heard some dramatic stories from medical acupuncturist colleagues that really would be hard to dismiss as non-specific effects, and from others I have heard relative ambivalence about the effects in hot flushes.

Personally I always try to consider mechanisms, and I wish researchers in the field would do the same before embarking on their trials. That is not intended as a criticism of this trial, but some consideration of mechanisms might allow us to explain all our data, including the contribution of this trial.

Acupuncture has recognised effects that are local to the needle, in the spinal cord (mainly in the segments stimulated) and in the brain (as well as humoral effects in CSF and blood). The latter are probably the mildest of the three categories, and require the best group of patient responders for them to be observable in clinical practice.

Menopausal hot flushes are explained by the effects of reduced oestrogens on the thermoregulatory centre in the anterior hypothalamus. It is certainly plausible that the neuro-inhibitory effects of endogenous opioids such as beta-endorphin, which we know can be released by acupuncture stimulation in experimental settings, could stablise neurones in the anterior hypothalamus that have become irritable due to a sudden drop in oestrogens.

So are endogenous opioids always released by acupuncture? Well, they and their effects seem to be measurable in experiments that use what I call proper acupuncture. That is, strong stimulation to deep somatic tissue. In the laboratory, and indeed in my clinic, this is only usually achieved in a palatable manner by electroacupuncture to muscle, although repeated manual stimulation every few minutes may have similar effects.

Ee et al used a relatively gentle acupuncture protocol, so they may have only generated measurable effects, based on mechanistic speculation, in the most responsive patients, perhaps less than 10%.

What does all this tell us? Well this trial clearly demonstrates that gentle acupuncture protocols generate effects in women with hot flushes via context rather than penetrating needling. In conditions that rely on central effects, I think we still need to consider stronger stimulation protocols and enriched enrollment in trials, ie preselecting responders before randomisation.

In my original comment I also predicted: “One does not need to be a clairvoyant to predict that acupuncturists will now find what they perceive as a flaw in the new study and claim that its results were false-negative.”

I am so glad Mike Cummings and the BMAS rushed to prove me right.

It’s so nice to know one can rely on someone in these uncertain times!

In 2009, we published a systematic review of studies testing acupuncture as a treatment of menopausal hot flushes. We searched the literature using 17 databases from inception to October 10, 2008, without language restrictions. We only included randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of acupuncture versus sham acupuncture. Their methodological quality was assessed using the modified Jadad score. In total, six RCTs could be included. Four RCTs compared the effects of acupuncture with penetrating sham acupuncture on non-acupuncture points. All of these trials failed to show specific effects on menopausal hot flush frequency, severity or index. One RCT found no effects of acupuncture on hot flush frequency and severity compared with penetrating sham acupuncture on acupuncture points that are not relevant for the treatment of hot flushes. The remaining RCT tested acupuncture against non-penetrating acupuncture on non-acupuncture points. Its results suggested favourable effects of acupuncture on menopausal hot flush severity. However, this study was too small to generate reliable findings. At the time, we concluded that sham-controlled RCTs fail to show specific effects of acupuncture for control of menopausal hot flushes. We also argued that more rigorous research is warranted.

It seems that such research has just become available.

The aim of a brand-new study – a stratified, blind (participants, outcome assessors, and investigators, but not treating acupuncturists were blinded to treatment allocation), parallel, randomized, sham-controlled trial with equal allocation – was to assess the efficacy of Chinese medicine acupuncture against sham acupuncture for menopausal hot flushes (HFs). It was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Women older than 40 years were recruited; they had to be in the late menopausal transition or postmenopause with at least 7 moderate HFs daily, meeting criteria for Chinese medicine diagnosis of kidney yin deficiency. These patients received 10 treatments over 8 weeks of either standardized Chinese medicine needle acupuncture designed to treat ‘kidney yin deficiency’ or they got the same amount of non-insertive sham acupuncture. The primary outcome was HF score at the end of treatment. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, anxiety, depression, and adverse events. Participants were assessed at 4 weeks, the end of treatment, and then 3 and 6 months after the end of treatment. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted with linear mixed-effects models.

In total, 327 women were randomly assigned to acupuncture (n = 163) or sham acupuncture (n = 164). At the end of treatment, 16% of participants in the acupuncture group and 13% in the sham group were lost to follow-up. Mean HF scores at the end of treatment period were 15.36 in the acupuncture group and 15.04 in the sham group. No serious adverse events were reported.

The authors concluded that Chinese medicine acupuncture was not superior to non-insertive sham acupuncture for women with moderately severe menopausal HFs.

The trial has several strengths: it includes a large sample size and the patients were adequately blinded to eliminate the effects of expectations. It was published in a top journal, and we can therefore assume that it was properly peer-reviewed. Combined with the evidence from our previous systematic review, this indicates that acupuncture has no effect beyond placebo.

In other words: ACUPUNCTURE IS NOTHING BUT A THEATRICAL PLACEBO.

One does not need to be a clairvoyant to predict that acupuncturists will now find what they perceive as a flaw in the new study and claim that its results were false-negative. Subsequently they will probably conduct their own trial which, because it is wide open to bias, will generate the finding they were hoping for.

This sequence of poor quality positive and high quality negative studies could go on ad infinitum.

This begs the question: how can such wasteful pseudo-research be stopped?

In theory, applications to ethics committees for research that is not aimed at answering open and important questions should get rejected. In practice, however, this is unlikely to happen. In my experience, the main reason preventing such actions is that, when it comes to alternative medicine, ethics committees tend to be too lenient (attempting to be ‘politically correct’), too uninterested (thinking that alternative medicine is not really a serious area of research) and too uninformed (failing to insist on a rigorous assessment of the already available evidence).

Hot flushes are a big problem; they are not life-threatening, of course, but they do make life a misery for countless menopausal women. Hormone therapy is effective, but many women have gone off the idea since we know that hormone therapy might increase their risk of getting cancer and cardiovascular disease. So, what does work and is also risk-free? Acupuncture?

Together with researchers from Quebec, we wanted to determine whether acupuncture is effective for reducing hot flushes and for improving the quality of life of menopausal women. We decided to do this in form of a Cochrane review which was just published.

We searched 16 electronic databases in order to identify all relevant studies and included all RCTs comparing any type of acupuncture to no treatment/control or other treatments. Sixteen studies, with a total of 1155 women, were eligible for inclusion. Three review authors independently assessed trial eligibility and quality, and extracted data. We pooled data where appropriate.

Eight studies compared acupuncture versus sham acupuncture. No significant difference was found between the groups for hot flush frequency, but flushes were significantly less severe in the acupuncture group, with a small effect size. There was substantial heterogeneity for both these outcomes. In a post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding studies of women with breast cancer, heterogeneity was reduced to 0% for hot flush frequency and 34% for hot flush severity and there was no significant difference between the groups for either outcome. Three studies compared acupuncture with hormone therapy, and acupuncture turned out to be associated with significantly more frequent hot flushes. There was no significant difference between the groups for hot flush severity. One study compared electro-acupuncture with relaxation, and there was no significant difference between the groups for either hot flush frequency or hot flush severity. Four studies compared acupuncture with waiting list or no intervention. Traditional acupuncture was significantly more effective in reducing hot flush frequency, and was also significantly more effective in reducing hot flush severity. The effect size was moderate in both cases.

For quality of life measures, acupuncture was significantly less effective than HT, but traditional acupuncture was significantly more effective than no intervention. There was no significant difference between acupuncture and other comparators for quality of life. Data on adverse effects were lacking.

Our conclusion: We found insufficient evidence to determine whether acupuncture is effective for controlling menopausal vasomotor symptoms. When we compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture, there was no evidence of a significant difference in their effect on menopausal vasomotor symptoms. When we compared acupuncture with no treatment there appeared to be a benefit from acupuncture, but acupuncture appeared to be less effective than HT. These findings should be treated with great caution as the evidence was low or very low quality and the studies comparing acupuncture versus no treatment or HT were not controlled with sham acupuncture or placebo HT. Data on adverse effects were lacking.

I still have to meet an acupuncturist who is not convinced that acupuncture is not an effective treatment for hot flushes. You only need to go on the Internet to see the claims that are being made along those lines. Yet this review shows quite clearly that it is not better than placebo. It also demonstrates that studies which do suggest an effect do so because they fail to adequately control for a placebo response. This means that the benefit patients and therapists observe in routine clinical practice is not due to the acupuncture per se, but to the placebo-effect.

And what could be wrong with that? Quite a bit, is my answer; here are just 4 things that immediately spring into my mind:

1) Arguably, it is dishonest and unethical to use a placebo on ill patients in routine clinical practice and charge for it pretending it is a specific and effective treatment.

2) Placebo-effects are unreliable, small and usually of short duration.

3) In order to generate a placebo-effect, I don’t need a placebo-therapy; an effective one administered with compassion does that too (and generates specific effects on top of that).

4) Not all placebos are risk-free. Acupuncture, for instance, has been associated with serious complications.

The last point is interesting also in the context of our finding that the RCTs analysed failed to mention adverse-effects. This is a phenomenon we observe regularly in studies of alternative medicine: trialists tend to violate the most fundamental rules of research ethics by simply ignoring the need to report adverse-effects. In plain English, this is called ‘scientific misconduct’. Consequently, we find very little published evidence on this issue, and enthusiasts claim their treatment is risk-free, simply because no risks are being reported. Yet one wonders to what extend systematic under-reporting is the cause of that impression!

So, what about the legion of acupuncturists who earn a good part of their living by recommending to their patients acupuncture for hot flushes?

They may, of course, not know about the evidence which shows that it is not more than a placebo. Would this be ok then? No, emphatically no! All clinicians have a duty to be up to date regarding the scientific evidence in relation to the treatments they use. A therapist who does not abide by this fundamental rule of medical ethics is, in my view, a fraud. On the other hand, some acupuncturists might be well aware of the evidence and employ acupuncture nevertheless; after all, it brings good money! Well, I would say that such a therapist is a fraud too.