caniosacral therapy

These days, it has become a rare event – I am speaking of me publishing a paper in the peer-reviewed medical literature. But it has just happened: Spanish researchers and I published a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of craniosacral therapy. Here is its abstract:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of craniosacral therapy (CST) in the management of any conditions. Two independent reviewers searched the PubMed, Physiotherapy Evidence Database, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Osteopathic Medicine Digital Library databases in August 2023, and extracted data from randomized controlled trials (RCT) evaluating the clinical effectiveness of CST. The PEDro scale and Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool were used to assess the potential risk of bias in the included studies. The certainty of the evidence of each outcome variable was determined using GRADEpro. Quantitative synthesis was carried out with RevMan 5.4 software using random effect models.

Fifteen RCTs were included in the qualitative and seven in the quantitative synthesis. For musculoskeletal disorders, the qualitative and quantitative synthesis suggested that CST produces no statistically significant or clinically relevant changes in pain and/or disability/impact in patients with headache disorders, neck pain, low back pain, pelvic girdle pain, or fibromyalgia. For non-musculoskeletal disorders, the qualitative and quantitative synthesis showed that CST was not effective for managing infant colic, preterm infants, cerebral palsy, or visual function deficits.

We concluded that the qualitative and quantitative synthesis of the evidence suggest that CST produces no benefits in any of the musculoskeletal or non-musculoskeletal conditions assessed. Two RCTs suggested statistically significant benefits of CST in children. However, both studies are seriously flawed, and their findings are thus likely to be false positive.

So, CST is not really an effective option for any condition.

Not a big surprise! After all, the assumptions on which CST is based fly in the face of science.

Since CST is nonetheless being used by many healthcare professionals, it is, I feel, important to state and re-state that CST is an implausible intervention that is not supported by clinical evidence. Hopefully then, one day, these practitioners will remember that their ethical obligation is to treat their patients not according to their beliefs but according to the best available evidence. And, hopefully, our modest paper will have helped rendering healthcare a little less irrational and somewhat more effective.

Craniosacral therapy (CST) is a widely taught component of osteopathic medical education. It is included in the standard curriculum of osteopathic medical schools, despite controversy surrounding its use. This paper seeks to systematically review randomized clinical trials (RCTs) assessing the clinical effectiveness of CST compared to standard care, sham treatment, or no treatment in adults and children.

A search of Embase, PubMed, and Scopus was conducted on 10/29/2023 with no restriction placed on the date of publication. Additionally, a Google Scholar search was conducted to capture grey literature. Backward citation searching was also implemented. All RCTs employing CST for any clinical outcome were included. Studies not available in English as well as any studies that did not report adequate data for inclusion in a meta-analysis were excluded. Multiple reviewers were used to assess for inclusions, disagreements were settled by consensus. PRISMA guidelines were followed in the reporting of this meta-analysis. Cochrane’s Risk of Bias 2 tool was used to assess for risk of bias. All data were extracted by multiple independent observers. Effect sizes were calculated using a Hedge’s G value (standardized mean difference) and aggregated using random effects models.

The primary study outcome was the effectiveness of CST for selected outcomes as applied to non-healthy adults or children and measured by standardized mean difference effect size. Twenty-four RCTs were included in the final meta-analysis with a total of 1,613 participants. When results were analyzed by primary outcome, no significant effects were found. When secondary outcomes were included, results showed that only Neonate health, structure (g = 0.66, 95% CI [0.30; 1.02], Prediction Interval [-0.73; 2.05]) and Pain, chronic somatic (g = 0.34, 95% CI [0.18; 0.50], Prediction Interval [-0.41; 1.09]) showed statistically significant effects. However, wide prediction intervals and high bias limit the real-world implications of this finding.

The authors concluded that CST did not demonstrate broad significance in this meta-analysis, suggesting limited usefulness in patient care for a wide range of indications.

To this, one should perhaps add that CST is one of those forms of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that is utterly implausible; there is not conceivable mechanism by which CST might work other than a placebo effects. Therefore, the finding that it is ineffective (positive effects on secondary outcomes are most likely due to residual bias and possibly fraud) is hardly surprising. The most sensible conclusion, in my view, is that CST too ridiculous to merit further research because that would, in effect, be an unethical waste of resources.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of craniosacral therapy on different features in migraine patients.

Fifty individuals with migraine were randomly divided into two groups (n = 25 per group):

- craniosacral therapy group (CTG),

- sham control group (SCG).

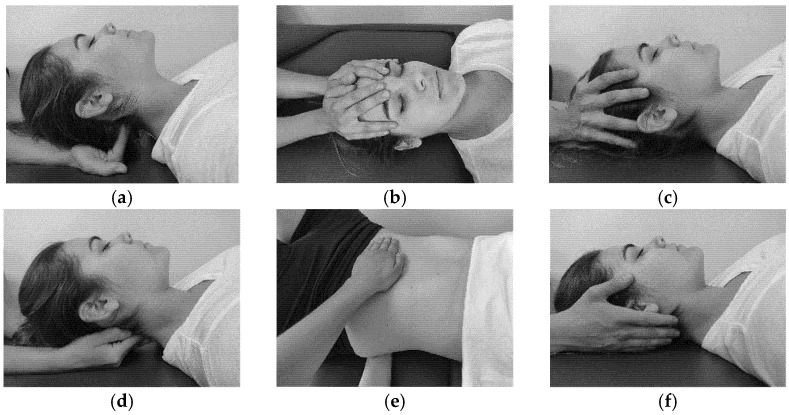

The interventions were carried out with the patient in the supine position. The CTG received a manual therapy treatment focused on the craniosacral region including five techniques, and the SCG received a hands-on placebo intervention. After the intervention, individuals remained supine with a neutral neck and head position for 10 min, to relax and diminish tension after treatment. The techniques were executed by the same experienced physiotherapist in both groups.

The analyzed variables were pain, migraine severity, and frequency of episodes, functional, emotional, and overall disability, medication intake, and self-reported perceived changes, at baseline, after a 4-week intervention, and at an 8-week follow-up.

After the intervention, the CTG significantly reduced pain (p = 0.01), frequency of episodes (p = 0.001), functional (p = 0.001) and overall disability (p = 0.02), and medication intake (p = 0.01), as well as led to a significantly higher self-reported perception of change (p = 0.01), when compared to SCG. The results were maintained at follow-up evaluation in all variables.

The authors concluded that a protocol based on craniosacral therapy is effective in improving pain, frequency of episodes, functional and overall disability, and medication intake in migraineurs. This protocol may be considered as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients.

Sorry, but I disagree!

And I have several reasons for it:

- The study was far too small for such strong conclusions.

- For considering any treatment as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients, we would need at least one independent replication.

- There is no plausible rationale for craniosacral therapy to work for migraine.

- The blinding of patients was not checked, and it is likely that some patients knew what group they belonged to.

- There could have been a considerable influence of the non-blinded therapists on the outcomes.

- There was a near-total absence of a placebo response in the control group.

Altogether, the findings seem far too good to be true.

I recently came across the ‘Sutherland Cranial College of Osteopathy’.

Sutherland Cranial College of Osteopathy?

Really?

I know what osteopathy is but what exactly is a ‘cranial college’?

Perhaps they mean ‘Sutherland College of Cranial Osteopathy’?

Anyway, they explain on their website that:

Cranial Osteopathy uses the same osteopathic principles that were described by Andrew Taylor Still, the founder of Osteopathy. Cranial osteopaths develop a very highly developed sense of palpation that enables them to feel subtle movements and imbalances in body tissues and to very gently support the body to release and re-balance itself. Treatment is so gentle that often patients are quite unaware that anything is happening. But the results of this subtle treatment can be dramatic, and it can benefit whole body health.

Sounds good?

I am sure you are now keen to become an expert in cranial osteopathy. The good news is that the college offers a course where this can be achieved in just 2 days! Here are the details:

This will be a spacious exploration of the nervous system. Neurological dysfunction and conditions feature greatly in our clinical work and this is especially the case in paediatric practice. The focus of this course is how to approach the nervous system in a fundamental way with reference to both current and historical ideas of neurological function. The following areas will be considered:

-

- Attaining stillness and grounding during palpation of the nervous system. It is within stillness that potency resides and when the treatment happens. The placement of attention.

- The pineal and its relationship to the tent, the pineal shift.

- The relations of the clivus and the central importance of the SBS, How do we assess and treat compression?

- The electromagnetic field and potency.

- The suspension of the cord within the spinal canal, the cervical and lumbar expansions.

- Listening posts for the central autonomic network.

Hawkwood College accommodation

Please be aware that accommodation at Hawkwood will be in shared rooms (single sex). Some single rooms are available on a first-come-first-served basis and will carry a supplement. Requesting a single room is not a guarantee that one will be provided.

£390.00 – £490.00

29 – 30 APRIL 2023 STROUD, UK

This will be a spacious exploration of the nervous system. Neurological dysfunction and conditions feature greatly in our clinical work and this is especially the case in pediatric practice.

_________________________

You see, not even expensive!

Go for it!!!

Oh, I see, you want to know what evidence there is that cranial osteopathy does more good than harm?

Right! Here is what I wrote in my recent book about it:

Craniosacral therapy (or craniosacral osteopathy) is a manual treatment developed by the US osteopath William Sutherland (1873–1953) and further refined by the US osteopath John Upledger (1932–2012) in the 1970s. The treatment consists of gentle touch and palpation of the synarthrodial joints of the skull and sacrum. Practitioners believe that these joints allow enough movement to regulate the pulsation of the cerebrospinal fluid which, in turn, improves what they call ‘primary respiration’. The notion of ‘primary respiration’ is based on the following 5 assumptions:

- inherent motility of the central nervous system

- fluctuation of the cerebrospinal fluid

- mobility of the intracranial and intraspinal dural membranes

- mobility of the cranial bones

- involuntary motion of the sacral bones.

A further assumption is that palpation of the cranium can detect a rhythmic movement of the cranial bones. Gentle pressure is used by the therapist to manipulate the cranial bones to achieve a therapeutic result. The degree of mobility and compliance of the cranial bones is minimal, and therefore, most of these assumptions lack plausibility.

The therapeutic claims made for craniosacral therapy are not supported by sound evidence. A systematic review of all 6 trials of craniosacral therapy concluded that “the notion that CST is associated with more than non‐specific effects is not based on evidence from rigorous RCTs.” Some studies seem to indicate otherwise, but they are of lamentable methodological quality and thus not reliable.

Being such a gentle treatment, craniosacral therapy is particularly popular for infants. But here too, the evidence fails to show effectiveness. A study concluded that “healthy preterm infants undergoing an intervention with craniosacral therapy showed no significant changes in general movements compared to preterm infants without intervention.”

The costs for craniosacral therapy are usually modest but, if the treatment is employed regularly, they can be substantial.

______________________________

As the college states “often patients are quite unaware that anything is happening”. Is it because nothing is happening? According to the evidence, the answer is YES.

So, on second thought, maybe you give the above course a miss?

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the effects and reliability of sham procedures in manual therapy (MT) trials in the treatment of back pain (BP) in order to provide methodological guidance for clinical trial development. Different databases were screened up to 20 August 2020. Randomised clinical trials involving adults affected by BP (cervical and lumbar), acute or chronic, were included. Hand contact sham treatment (ST) was compared with different MT (physiotherapy, chiropractic, osteopathy, massage, kinesiology, and reflexology) and to no treatment. Primary outcomes were BP improvement, the success of blinding, and adverse effect (AE). Secondary outcomes were the number of drop-outs. Dichotomous outcomes were analysed using risk ratio (RR), continuous using mean difference (MD), 95% CIs. The minimal clinically important difference was 30 mm changes in pain score.

A total of 24 trials were included involving 2019 participants. Different manual treatments were provided:

- SM/chiropractic (7 studies, 567 participants).

- Osteopathy (5 trials, 645 participants).

- Kinesiology (1 trial, 58 participants).

- Articular mobilisations (6 trials, 445 participants).

- Muscular release (5 trials, 304 participants).

Very low evidence quality suggests clinically insignificant pain improvement in favour of MT compared with ST (MD 3.86, 95% CI 3.29 to 4.43) and no differences between ST and no treatment (MD -5.84, 95% CI -20.46 to 8.78).ST reliability shows a high percentage of correct detection by participants (ranged from 46.7% to 83.5%), spinal manipulation being the most recognised technique. Low quality of evidence suggests that AE and drop-out rates were similar between ST and MT (RR AE=0.84, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.28, RR drop-outs=0.98, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.25). A similar drop-out rate was reported for no treatment (RR=0.82, 95% 0.43 to 1.55).

Forest plot of comparison ST versus MT in back pain outcome at short term. MT, manual therapy; ST, sham treatment.

The authors concluded that MT does not seem to have clinically relevant effect compared with ST. Similar effects were found with no treatment. The heterogeneousness of sham MT studies and the very low quality of evidence render uncertain these review findings. Future trials should develop reliable kinds of ST, similar to active treatment, to ensure participant blinding and to guarantee a proper sample size for the reliable detection of clinically meaningful treatment effects.

Essentially these findings suggest that the effects patients experience after MT are not due to MT per see but to placebo effects. The review could be criticised because of the somewhat odd mix of MTs lumped together in one analysis. Yet, I think it is fair to point out that most of the studies were of chiropractic and osteopathy. Thus, this review implies that chiropractic and osteopathy are essentially placebo treatments.

The authors of the review also provide this further comment:

Similar findings were found in other reviews conducted on LBP. Ruddock et al included studies where SM was compared with what authors called ‘an effective ST’, namely a credible sham manipulation that physically mimics the SM. Pooled data from four trials showed a very small and not clinically meaningful effect in favour of MT.52

Rubinstein et al 53 compared SM and mobilisation techniques to recommended, non-recommended therapies and to ST. Their findings showed that 5/47 studies included attempted to blind patients to the assigned intervention by providing an ST. Of these five trials, two were judged at unclear risk of participants blinding. The authors also questioned the need for additional studies on this argument, as during the update of their review they found recent small pragmatic studies with high risk of bias. We agree with Rubinstein et al that recent studies included in this review did not show a higher quality of evidence. The development of RCT with similar characteristic will probably not add any proof of evidence on MT and ST effectiveness.53

If we agree that chiropractic and osteopathy are placebo therapies, we might ask whether they should have a place in the management of BP. Considering the considerable risks associated with them, I feel that the answer is obvious and simple:

NO!

I have been sceptical about Craniosacral Therapy (CST) several times (see for instance here, here and here). Now, a new paper might change all this:

The systematic review assessed the evidence of Craniosacral Therapy (CST) for the treatment of chronic pain. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of CST in chronic pain patients were eligible. Pain intensity and functional disability were the primary outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool.

Ten RCTs with a total of 681 patients suffering from neck and back pain, migraine, headache, fibromyalgia, epicondylitis, and pelvic girdle pain were included.

Compared to treatment as usual, CST showed greater post intervention effects on:

- pain intensity (SMD=-0.32, 95%CI=[−0.61,-0.02])

- disability (SMD=-0.58, 95%CI=[−0.92,-0.24]).

Compared to manual/non-manual sham, CST showed greater post intervention effects on:

- pain intensity (SMD=-0.63, 95%CI=[−0.90,-0.37])

- disability (SMD=-0.54, 95%CI=[−0.81,-0.28]) ;

Compared to active manual treatments, CST showed greater post intervention effects on:

- pain intensity (SMD=-0.53, 95%CI=[−0.89,-0.16])

- disability (SMD=-0.58, 95%CI=[−0.95,-0.21]) .

At six months, CST showed greater effects on pain intensity (SMD=-0.59, 95%CI=[−0.99,-0.19]) and disability (SMD=-0.53, 95%CI=[−0.87,-0.19]) versus sham. Secondary outcomes were all significantly more improved in CST patients than in other groups, except for six-month mental quality of life versus sham. Sensitivity analyses revealed robust effects of CST against most risk of bias domains. Five of the 10 RCTs reported safety data. No serious adverse events occurred. Minor adverse events were equally distributed between the groups.

The authors concluded that, in patients with chronic pain, this meta-analysis suggests significant and robust effects of CST on pain and function lasting up to six months. More RCTs strictly following CONSORT are needed to further corroborate the effects and safety of CST on chronic pain.

Robust effects! This looks almost convincing, particularly to an uncritical proponent of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). However, a bit of critical thinking quickly discloses numerous problems, not with this (technically well-made) review, but with the interpretation of its results and the conclusions. Let me mention a few that spring into my mind:

- The literature searches were concluded in August 2018; why publish the paper only in 2020? Meanwhile, there might have been further studies which would render the review outdated even on the day it was published. (I know that there are many reasons for such a delay, but a responsible journal editor must insist on an update of the searches before publication.)

- Comparisons to ‘treatment as usual’ do not control for the potentially important placebo effects of CST and thus tell us nothing about the effectiveness of CST per se.

- The same applies to comparisons to ‘active’ manual treatments and ‘non-manual’ sham (the purpose of a sham is to blind patients; a non-manual sham defies this purpose).

- This leaves us with exactly two trials employing a sham that might have been sufficiently credible to be able to fool patients into believing that they were receiving the verum.

- One of these trials (ref 44) is far too flimsy to be taken seriously: it was tiny (n=23), did not adequately blind patients, and failed to mention adverse effects (thus violating research ethics [I cannot take such trials seriously]).

- The other trial (ref 41) is by the same research group as the review, and the authors award themselves a higher quality score than any other of the primary studies (perhaps even correctly, because the other trials are even worse). Yet, their study has considerable weaknesses which they fail to discuss: it was small (n=54), there was no check to see whether patient-blinding was successful, and – as with all the CST studies – the therapist was, of course, no blind. The latter point is crucial, I think, because patients can easily be influenced by the therapists via verbal or non-verbal communication to report the findings favoured by the therapist. This means that the small effects seen in such studies are likely to be due to this residual bias and thus have nothing to do with the intervention per se.

- Despite the fact that the review findings depend critically on their own primary study, the authors of the review declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Considering all this plus the rather important fact that CST completely lacks biological plausibility, I do not think that the conclusions of the review are warranted. I much prefer the ones from my own systematic review of 2012. It included 6 RCTs (all of which were burdened with a high risk of bias) and concluded that the notion that CST is associated with more than non‐specific effects is not based on evidence from rigorous RCTs.

So, why do the review authors first go to the trouble of conducting a technically sound systematic review and meta-analysis and then fail utterly to interpret its findings critically? I might have an answer to this question. Back in 2016, I included the head of this research group, Gustav Dobos, into my ‘hall of fame’ because he is one of the many SCAM researchers who never seem to publish a negative result. This is what I then wrote about him:

Dobos seems to be an ‘all-rounder’ whose research tackles a wide range of alternative treatments. That is perhaps unremarkable – but what I do find remarkable is the impression that, whatever he researches, the results turn out to be pretty positive. This might imply one of two things, in my view:

- all alternative therapies are effective,

- the ‘Trustworthiness Index’ of Prof Dobos is unusual.

I let my readers chose which possibility they deem to be more likely.

As most of us know, the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) can be problematic; its use in children is often most problematic:

- There are hardly any SCAMs that have been shown to work for paediatric conditions.

- Most SCAMs can cause considerable harm to children.

- Some might even amount to child abuse.

- Most SCAM practitioners lack adequate training to treat children.

- Many SCAM providers offer dangerous advice to parents.

- Parents are sometimes unable to differentiate between nonsense and medicine.

- Informed consent can present a trick subject when treating children.

In this context, the statement from the ‘Spanish Association Of Paediatrics Medicines Committee’ is of particular value and importance:

Currently, there are some therapies that are being practiced without adjusting to the available scientific evidence. The terminology is confusing, encompassing terms such as “alternative medicine”, “natural medicine”, “complementary medicine”, “pseudoscience” or “pseudo-therapies”. The Medicines Committee of the Spanish Association of Paediatrics considers that no health professional should recommend treatments not supported by scientific evidence. Also, diagnostic and therapeutic actions should be always based on protocols and clinical practice guidelines. Health authorities and judicial system should regulate and regularize the use of alternative medicines in children, warning parents and prescribers of possible sanctions in those cases in which the clinical evolution is not satisfactory, as well responsibilities are required for the practice of traditional medicine, for health professionals who act without complying with the “lex artis ad hoc”, and for the parents who do not fulfill their duties of custody and protection. In addition, it considers that, as already has happened, Professional Associations should also sanction, or at least reprobate or correct, those health professionals who, under a scientific recognition obtained by a university degree, promote the use of therapies far from the scientific method and current evidence, especially in those cases in which it is recommended to replace conventional treatment with pseudo-therapy, and in any case if said substitution leads to a clinical worsening that could have been avoided.

Of course, not all SCAM professions focus on children. The following, however, treat children regularly:

- acupuncturists

- anthroposophical doctors

- chiropractors

- craniosacral therapists

- energy healers

- herbalists

- homeopaths

- naturopaths

- osteopaths

I believe that all SCAM providers who treat children should consider the above statement very carefully. They must ask themselves whether there is good evidence that their treatments generate more good than harm for their patients. If the answer is not positive, they should stop. If they don’t, they should realise that they behave unethically and quite possibly even illegally.

Cranio-sacral therapy is firstly implausible, and secondly it lacks evidence of effectiveness (see for instance here, here, here and here). Yet, some researchers are nevertheless not deterred to test it in clinical trials. While this fact alone might be seen as embarrassing, the study below is a particular and personal embarrassment to me, in fact, I am shocked by it and write these lines with considerable regret.

Why? Bear with me, I will explain later.

The purpose of this trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field in temporomandibular disorders. Forty female subjects with temporomandibular disorders lasting at least three months were included. At enrollment, subjects were randomly assigned into two groups: (1) osteopathic manipulative treatment group (n=20) and (2) osteopathy in the cranial field [craniosacral therapy for you and me] group (n=20). Examinations were performed at baseline (E0) and at the end of the last treatment (E1), and consisted of subjective pain intensity with the Visual Analog Scale, Helkimo Index and SF-36 Health Survey. Subjects had five treatments, once a week. 36 subjects completed the study.

Patients in both groups showed significant reduction in Visual Analog Scale score (osteopathic manipulative treatment group: p = 0.001; osteopathy in the cranial field group: p< 0.001), Helkimo Index (osteopathic manipulative treatment group: p = 0.02; osteopathy in the cranial field group: p = 0.003) and a significant improvement in the SF-36 Health Survey – subscale “Bodily Pain” (osteopathic manipulative treatment group: p = 0.04; osteopathy in the cranial field group: p = 0.007) after five treatments (E1). All subjects (n = 36) also showed significant improvements in the above named parameters after five treatments (E1): Visual Analog Scale score (p< 0.001), Helkimo Index (p< 0.001), SF-36 Health Survey – subscale “Bodily Pain” (p = 0.001). The differences between the two groups were not statistically significant for any of the three endpoints.

The authors concluded that both therapeutic modalities had similar clinical results. The findings of this pilot trial support the use of osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field as an effective treatment modality in patients with temporomandibular disorders. The positive results in both treatment groups should encourage further research on osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field and support the importance of an interdisciplinary collaboration in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Implications for rehabilitation Temporomandibular disorders are the second most prevalent musculoskeletal condition with a negative impact on physical and psychological factors. There are a variety of options to treat temporomandibular disorders. This pilot study demonstrates the reduction of pain, the improvement of temporomandibular joint dysfunction and the positive impact on quality of life after osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field. Our findings support the use of osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field and should encourage further research on osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Rehabilitation experts should consider osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field as a beneficial treatment option for temporomandibular disorders.

This study has so many flaws that I don’t know where to begin. Here are some of the more obvious ones:

- There is, as already mentioned, no rationale for this study. I can see no reason why craniosacral therapy should work for the condition. Without such a rationale, the study should never even have been conceived.

- Technically, this RCTs an equivalence study comparing one therapy against another. As such it needs to be much larger to generate a meaningful result and it also would require a different statistical approach.

- The authors mislabelled their trial a ‘pilot study’. However, a pilot study “is a preliminary small-scale study that researchers conduct in order to help them decide how best to conduct a large-scale research project. Using a pilot study, a researcher can identify or refine a research question, figure out what methods are best for pursuing it, and estimate how much time and resources will be necessary to complete the larger version, among other things.” It is not normally a study suited for evaluating the effectiveness of a therapy.

- Any trial that compares one therapy of unknown effectiveness to another of unknown effectiveness is a complete and utter nonsense. Equivalent studies can only ever make sense, if one of the two treatments is of proven effectiveness – think of it as a mathematical equation: one equation with two unknowns is unsolvable.

- Controlled studies such as RCTs are for comparing the outcomes of two or more groups, and only between-group differences are meaningful results of such trials.

- The ‘positive results’ which the authors mention in their conclusions are meaningless because they are based on such within-group changes and nobody can know what caused them: the natural history of the condition, regression towards the mean, placebo-effects, or other non-specific effects – take your pick.

- The conclusions are a bonanza of nonsensical platitudes and misleading claims which do not follow from the data.

As regular readers of this blog will doubtlessly have noticed, I have seen plenty of similarly flawed pseudo-research before – so, why does this paper upset me so much? The reason is personal, I am afraid: even though I do not know any of the authors in person, I know their institution more than well. The study comes from the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Medical University of Vienna, Austria. I was head of this department before I left in 1993 to take up the Exeter post. And I had hoped that, even after 25 years, a bit of the spirit, attitude, knowhow, critical thinking and scientific rigor – all of which I tried so hard to implant in my Viennese department at the time – would have survived.

Perhaps I was wrong.

Recently, the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) together with the UK General Osteopathic Council (GOsC) have sent new guidance to over 4,800 UK osteopaths on the GOsC register. The guidance covers marketing claims for pregnant women, children and babies. It also provides examples of what kind of claims can, and can’t, be made for these patient groups.

Regulated by statute, osteopaths may offer advice on, diagnosis of and treatment for conditions only if they hold convincing evidence. Claims for treating conditions specific to pregnant women, children and babies are not supported by the evidence available to date.

The new ASA guidance is intended to help osteopaths talk about the healthcare they provide in a way that complies with the Advertising Codes and to protect consumers from being misled. It provides some basic principles and many examples of claims that are, and aren’t, acceptable. The ASA hopes it will provide greater clarity to osteopaths on how to advertise osteopathic care for pregnant women, children and babies responsibly.

Specifically, the guidance points out that “osteopaths may make claims to treat general as well as specific patient populations, including pregnant women, children and babies, provided they are qualified to do so. Osteopaths may not claim to treat conditions or symptoms presented as specific to these groups (e.g. colic, growing pains, morning sickness) unless the ASA or CAP has seen evidence for the efficacy of osteopathy for the particular condition claimed, or for which the advertiser holds suitable substantiation. Osteopaths may refer to the provision of general health advice to specific patient populations, providing they do not make implied and unsubstantiated treatment claims for conditions.”

Examples of claims previously made by UK osteopaths which are “unlikely to be acceptable” include:

- Osteopaths often work with lactation consultations where babies are having difficulty feeding.

- Osteopaths are qualified to advise and treat patients across the full breadth of primary care practice.

- Osteopaths often work with crying, unsettled babies.

- Birth is a stressful process for babies.

- Babies’ skulls are susceptible to strain or moulding, leading to asymmetrical or flattened head shapes. This usually resolves quickly but can sometimes be retained. Osteopathy can help.

- If your baby suffers from excessive crying, sometimes known as colic, osteopathy might help.

- Children often complain of growing pains in their muscles and joints; your osteopath can treat these pains.

- Osteopathy can help your baby recover from the trauma of birth; I will gently massage your baby’s skull.

- Midwives often recommend an osteopathic check-up for babies after birth.

- Osteopathy can help with breast soreness or mastitis after birth.

- If your baby is having difficulty breastfeeding, osteopathy might be able to help.

- Many pregnant women experience pain in the pelvic girdle area. Osteopaths offer safe, gentle manipulation and stretches.

- Many pregnant women find osteopathy relieves common symptoms such as nausea and heartburn.

- Use of osteopathy can limit perineum or pelvic floor trauma.

- If your baby suffers from constipation then osteopathy could help.

- Osteopathy can also play an important preventative role in the care of a baby, child or teenager and bring the body back to a state of balance in health.

- In assessing a newborn baby, an osteopath checks for asymmetry or tension in the pelvis, spine and head, and ensures that a good breathing pattern has been established.

- Cranial osteopathy releases stresses and strains in the skull and throughout the body.

- Osteopaths can feel involuntary motion and mechanisms within the body.

- Cranial osteopathy aims to reduce restrictions in movement.

Elsewhere in the ASA announcement, we find the statement that “The effectiveness of osteopathy for treating some conditions is underpinned by robust evidence”. The two examples provided are rheumatic pain and joint pain. I have to say I was mystified by this. I am not aware of robust evidence for these two indications. Perhaps someone could help me out here and provide some references?

The only condition for which there is enough encouraging evidence is, as far, as I know low back pain – and even here I would not call the evidence ‘robust’. Am I mistaken? If you think so, please supply the evidence with links to the references.

But, in general, the new guidance is certainly a step in the right direction. Now we have to wait and see whether osteopaths change their advertising and behaviour accordingly and what happens to those who don’t.

WATCH THIS SPACE

Cranio-sacral therapy has been a subject on this blog before, for instance here, here and here. The authors of this single-blind, randomized trial explain in the introduction of their paper that “cranio-sacral therapy is an alternative and complementary therapy based on the theory that restricted movement at the cranial sutures of the skull negatively affect rhythmic impulses conveyed through the cerebral spinal fluid from the cranium to the sacrum. Restriction within the cranio-sacral system can affect its components: the brain, spinal cord, and protective membranes. The brain is said to produce involuntary, rhythmic movements within the skull. This movement involves dilation and contraction of the ventricles of the brain, which produce the circulation of the cerebral spinal fluid. The theory states that this fluctuation mechanism causes reciprocal tension within the membranes, transmitting motion to the cranial bones and the sacrum. Cranio-sacral therapy and cranial osteopathic manual therapy originate from the observations made by William G. Sutherland, who said that the bones of the human skeleton have mobility. These techniques are based mainly on the study of anatomic and physiologic mechanisms in the skull and their relation to the body as a whole, which includes a system of diagnostic and therapeutic techniques aimed at treatment and prevention of diseases. These techniques are based on the so-called primary respiratory movement, which is manifested in the mobility of the cranial bones, sacrum, dura, central nervous system, and cerebrospinal fluid. The main difference between the two therapies is that cranial osteopathy, in addition to a phase that works in the direction of the lesion (called the functional phase), also uses a phase that worsens the injury, which is called structural phase.”

With this study, the researchers wanted to evaluate the effects of cranio-sacral therapy on disability, pain intensity, quality of life, and mobility in patients with low back pain. Sixty-four patients with chronic non-specific low back pain were assigned to an experimental group receiving 10 sessions of craniosacral therapy, or to the control group receiving 10 sessions of classic massage. Craniosacral therapy took 50 minutes and was conducted as follows: With pelvic diaphragm release, palms are placed in transverse position on the superior aspect of the pubic bone, under the L5–S1 sacrum, and finger pads are placed on spinal processes. With respiratory diaphragm release, palms are placed transverse under T12/L1 so that the spine lies along the start of fingers and the border of palm, and the anterior hand is placed on the breastbone. For thoracic inlet release, the thumb and index finger are placed on the opposite sides of the clavicle, with the posterior hand/palm of the hand cupping C7/T1. For the hyoid release, the thumb and index finger are placed on the hyoid, with the index finger on the occiput and the cupping finger pads on the cervical vertebrae. With the sacral technique for stabilizing L5/sacrum, the fingers contact the sulcus and the palm of the hand is in contact with the distal part of the sacral bone. The non-dominant hand of the therapist rested over the pelvis, with one hand on one iliac crest and the elbow/forearm of the other side over the other iliac crest. For CV-4 still point induction, thenar pads are placed under the occipital protuberance, avoiding mastoid sutures. Classic massage protocol was compounded by the following sequence techniques of soft tissue massage on the low back: effleurage, petrissage, friction, and kneading. The maneuvers are performed with surface pressure, followed by deep pressure and ending with surface pressure again. The techniques took 30 minutes.

Disability (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire RMQ, and Oswestry Disability Index) was the primary endpoint. Other outcome measures included the pain intensity (10-point numeric pain rating scale), kinesiophobia (Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia), isometric endurance of trunk flexor muscles (McQuade test), lumbar mobility in flexion, hemoglobin oxygen saturation, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hemodynamic measures (cardiac index), and biochemical analyses of interstitial fluid. All outcomes were measured at baseline, after treatment, and one-month follow-up.

No statistically significant differences were seen between groups for the main outcome of the study, the RMQ. However, patients receiving craniosacral therapy experienced greater improvement in pain intensity (p ≤ 0.008), hemoglobin oxygen saturation (p ≤ 0.028), and systolic blood pressure (p ≤ 0.029) at immediate- and medium-term and serum potassium (p = 0.023) level and magnesium (p = 0.012) at short-term than those receiving classic massage.

The authors concluded that 10 sessions of cranio-sacral therapy resulted in a statistically greater improvement in pain intensity, hemoglobin oxygen saturation, systolic blood pressure, serum potassium, and magnesium level than did 10 sessions of classic massage in patients with low back pain.

Given the results of this study, the conclusion is surprising. The primary outcome measure failed to show an inter-group difference; in other words, the results of this RCT were essentially negative. To use secondary endpoints – most of which are irrelevant for the study’s aim – in order to draw a positive conclusion seems odd, if not misleading. These positive findings are most likely due to the lack of patient-blinding or to the 200 min longer attention received by the verum patients. They are thus next to meaningless.

In my view, this publication is yet another example of an attempt to turn a negative into a positive result. This phenomenon seems embarrassingly frequent in alternative medicine. It goes without saying that it is not just misleading but also dishonest and unethical.