arthritis

There is much debate about the usefulness of chiropractic. Specifically, many people doubt that their chiropractic spinal manipulations generate more good than harm, particularly for conditions which are not related to the spine. But do chiropractors treat such conditions frequently and, if yes, what techniques do they employ?

This investigation was aimed at describing the clinical practices of chiropractors in Victoria, Australia. It was a cross-sectional survey of 180 chiropractors in active clinical practice in Victoria who had been randomly selected from the list of 1298 chiropractors registered on Chiropractors Registration Board of Victoria. Twenty-four chiropractors were ineligible, 72 agreed to participate, and 52 completed the study.

Each participating chiropractor documented encounters with up to 100 consecutive patients. For each chiropractor-patient encounter, information collected included patient health profile, patient reasons for encounter, problems and diagnoses, and chiropractic care.

Data were collected on 4464 chiropractor-patient encounters between 11 December 2010 and 28 September 2012. In most (71%) cases, patients were aged 25-64 years; 1% of encounters were with infants. Musculoskeletal reasons for the consultation were described by patients at a rate of 60 per 100 encounters, while maintenance and wellness or check-up reasons were described at a rate of 39 per 100 encounters. Back problems were managed at a rate of 62 per 100 encounters.

The most frequent care provided by the chiropractors was spinal manipulative therapy and massage. The table shows the precise conditions treated

Distribution of problems managed (20 most frequent problems), as reported by chiropractors

| Problem group | No. (%) of recorded diagnoses* (n = 5985) | Rate per 100 encounters (n = 4417) | 95% CI | ICC |

| Back problem | 2757 (46.07%) | 62.42 | (55.24–70.53) | 0.312 |

| Neck problem | 683 (11.41%) | 15.46 | (11.23–21.30) | 0.233 |

| Muscle problem | 434 (7.25%) | 9.83 | (6.64–14.55) | 0.207 |

| Health maintenance or preventive care | 254 (4.24%) | 5.75 | (3.24–10.22) | 0.251 |

| Back syndrome with radiating pain | 215 (3.59%) | 4.87 | (2.91–8.14) | 0.165 |

| Musculoskeletal symptom or complaint, or other | 219 (3.66%) | 4.96 | (2.39–10.28) | 0.350 |

| Headache | 179 (2.99%) | 4.05 | (2.87–5.71) | 0.053 |

| Sprain or strain of joint | 167 (2.79%) | 3.78 | (2.30–6.22) | 0.115 |

| Shoulder problem | 87 (1.45%) | 1.97 | (1.37–2.83) | 0.022 |

| Nerve-related problem | 62 (1.04%) | 1.40 | (0.72–2.75) | 0.072 |

| General symptom or complaint, other | 51 (0.85%) | 1.15 | (0.22–6.06) | 0.407 |

| Bursitis, tendinitis or synovitis | 47 (0.79%) | 1.06 | (0.71–1.60) | 0.011 |

| Kyphosis and scoliosis | 47 (0.79%) | 1.06 | (0.65–1.75) | 0.023 |

| Foot or toe symptom or complaint | 48 (0.80%) | 1.09 | (0.41–2.87) | 0.123 |

| Ankle problem | 46 (0.77%) | 1.04 | (0.40–2.69) | 0.112 |

| Osteoarthrosis, other (not spine) | 39 (0.65%) | 0.88 | (0.51–1.53) | 0.023 |

| Hip symptom or complaint | 35 (0.58%) | 0.79 | (0.53–1.19) | 0.006 |

| Leg or thigh symptom or complaint | 35 (0.58%) | 0.79 | (0.49–1.28) | 0.012 |

| Musculoskeletal injury | 33 (0.55%) | 0.75 | (0.45–1.24) | 0.013 |

| Depression | 29 (0.48%) | 0.66 | (0.10–4.23) | 0.288 |

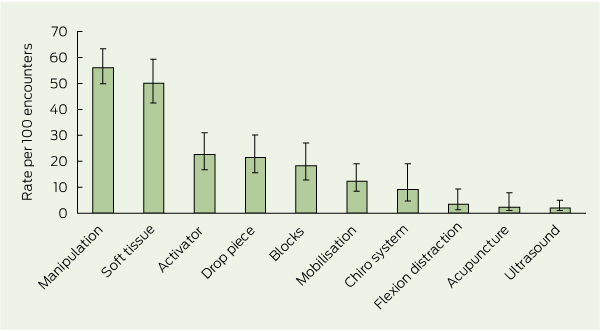

These findings are impressive in that they suggest that most Australian chiropractors treat non-spinal conditions for which there is no evidence that the most frequently used interventions are effective. The treatments employed are depicted in this graph:

Distribution of techniques and care provided by chiropractors, with 95% CI

[Activator = hand-held spring-loaded device that delivers an impulse to the spine. Drop piece = chiropractic treatment table with a segmented drop system which quickly lowers the section of the patient’s body corresponding with the spinal region being treated. Blocks = wedge-shaped blocks placed under the pelvis.

Chiro system = chiropractic system of care, eg, Applied Kinesiology, Sacro-Occipital Technique, Neuroemotional Technique. Flexion distraction = chiropractic treatment table that flexes in the middle to provide traction and mobilisation to the lumbar spine.]

There is no good evidence I know of demonstrating these techniques to be effective for the majority of the conditions listed in the above table.

A similar bone of contention is the frequent use of ‘maintenance’ and ‘wellness’ care. The authors of the article comment: The common use of maintenance and wellness-related terms reflects current debate in the chiropractic profession. “Chiropractic wellness care” is considered by an indeterminate proportion of the profession as an integral part of chiropractic practice, with the belief that regular chiropractic care may have value in maintaining and promoting health, as well as preventing disease. The definition of wellness chiropractic care is controversial, with some chiropractors promoting only spine care as a form of wellness, and others promoting evidence-based health promotion, eg, smoking cessation and weight reduction, alongside spine care. A 2011 consensus process in the chiropractic profession in the United States emphasised that wellness practice must include health promotion and education, and active strategies to foster positive changes in health behaviours. My own systematic review of regular chiropractic care, however, shows that the claimed effects are totally unproven.

One does not need to be overly critical to conclude from all this that the chiropractors surveyed in this investigation earn their daily bread mostly by being economical with the truth regarding the lack of evidence for their actions.

A recently published study by Danish researchers aimed at comparing the effectiveness of a patient education (PEP) programme with or without the added effect of chiropractic manual therapy (MT) to a minimal control intervention (MCI). Its results seem to indicate that chiropractic MT is effective. Is this the result chiropractors have been waiting for?

To answer this question, we need to look at the trial and its methodology in more detail.

A total of 118 patients with clinical and radiographic unilateral hip osteoarthritis (OA) were randomized into one of three groups: PEP, PEP+ MT or MCI. The PEP was taught by a physiotherapist in 5 sessions. The MT was delivered by a chiropractor in 12 sessions, and the MCI included a home stretching programme. The primary outcome measure was the self-reported pain severity on an 11-box numeric rating scale immediately following the 6-week intervention period. Patients were subsequently followed for one year.

The primary analyses included 111 patients. In the PEP+MT group, a statistically and clinically significant reduction in pain severity of 1.9 points was noted compared to the MCI of 1.90. The number needed to treat for PEP+MT was 3. No difference was found between the PEP and the MCI groups. At 12 months, the difference favouring PEP+MT was maintained.

The authors conclude that for primary care patients with osteoarthritis of the hip, a combined intervention of manual therapy and patient education was more effective than a minimal control intervention. Patient education alone was not superior to the minimal control intervention.

This is an interesting, pragmatic trial with a result suggesting that chiropractic MT in combination with PEP is effective in reducing the pain of hip OA. One could easily argue about the small sample size, the need for independent replication etc. However, my main concern is the fact that the findings can be interpreted in not just one but in at least two very different ways.

The obvious explanation would be that chiropractic MT is effective. I am sure that chiropractors would be delighted with this conclusion. But how sure can we be that it would reflect the truth?

I think an alternative explanation is just as (possibly more) plausible: the added time, attention and encouragement provided by the chiropractor (who must have been aware what was at stake and hence highly motivated) was the effective element in the MT-intervention, while the MT per se made little or no difference. The PEP+MT group had no less than 12 sessions with the chiropractor. We can assume that this additional care, compassion, empathy, time, encouragement etc. was a crucial factor in making these patients feel better and in convincing them to adhere more closely to the instructions of the PEP. I speculate that these factors were more important than the actual MT itself in determining the outcome.

In my view, such critical considerations regarding the trial methodology are much more than an exercise in splitting hair. They are important in at least two ways.

Firstly, they remind us that clinical trials, whenever possible, should be designed such that they allow only one interpretation of their results. This can sometimes be a problem with pragmatic trials of this nature. It would be wise, I think, to conduct pragmatic trials only of interventions which have previously been proven to work. To the best of my knowledge, chiropractic MT as a treatment for hip OA does not belong to this category.

Secondly, it seems crucial to be aware of such methodological issues and to consider them carefully before research findings are translated into clinical practice. If not, we might end up with therapeutic decisions (or guidelines) which are quite simply not warranted.

I would not be in the least surprised, if chiropractic interest groups were to use the current findings for promoting chiropractic in hip-OA. But what, if the MT per se was ineffective, while the additional care, compassion and encouragement was? In this case, we would not need to recruit (and pay for) chiropractors and put up with the considerable risks chiropractic treatments can entail; we would merely need to modify the PE programme such that patients are better motivated to adhere to it.

As it stands, the new study does not tell us much that is of any practical use. In my view, it is a pragmatic trial which cannot readily be translated into evidence-based practice. It might get interpreted as good news for chiropractic but, in fact, it is not.

In my very first post on this blog, I proudly pronounced that this would not become one of those places where quack-busters have field-day. However, I am aware that, so far, I have not posted many complimentary things about alternative medicine. My ‘excuse’ might be that there are virtually millions of sites where this area is uncritically promoted and very few where an insider dares to express a critical view. In the interest of balance, I thus focus of critical assessments.

Yet I intend, of course, report positive news when I think it is relevant and sound. So, today I shall discuss a new trial which is impressively sound and generates some positive results:

French rheumatologists conducted a prospective, randomised, double blind, parallel group, placebo controlled trial of avocado-soybean-unsaponifiables (ASU). This dietary supplement has complex pharmacological activities and has been used since years for osteoarthritis (OA) and other conditions. The clinical evidence has, so far, been encouraging, albeit not entirely convincing. My own review arrived at the conclusion that “the majority of rigorous trial data available to date suggest that ASU is effective for the symptomatic treatment of OA and more research seems warranted. However, the only real long-term trial yielded a largely negative result”.

For the new trial, patients with symptomatic hip OA and a minimum joint space width (JSW) of the target hip between 1 and 4 mm were randomly assigned to three years of 300 mg/day ASU-E or placebo. The primary outcome was JSW change at year 3, measured radiographically at the narrowest point.

A total of 399 patients were randomised. Their mean baseline JSW was 2.8 mm. There was no significant difference on mean JSW loss, but there was 20% less progressors in the ASU than in the placebo group (40% vs 50%, respectively). No difference was observed in terms of clinical outcomes. Safety was excellent.

The authors concluded that 3 year treatment with ASU reduces the speed of JSW narrowing, indicating a potential structure modifying effect in hip OA. They cautioned that their results require independent confirmation and that the clinical relevance of their findings require further assessment.

I like this study, and here are just a few reasons why:

It reports a massive research effort; I think anyone who has ever attempted a 3-year RCT might agree with this view.

It is rigorous; all the major sources of bias are excluded as far as humanly possible.

It is well-reported; all the essential details are there and anyone who has the skills and funds would be able to attempt an independent replication.

The authors are cautious in their interpretation of the results.

The trial tackles an important clinical problem; OA is common and any treatment that helps without causing significant harm would be more than welcome.

It yielded findings which are positive or at least promising; contrary to what some people seem to believe, I do like good news as much as anyone else.

I WISH THERE WERE MORE ALT MED STUDIES/RESEARCHERS OF THIS CALIBER!

Musculoskeletal and rheumatic conditions, often just called “arthritis” by lay people, bring more patients to alternative practitioners than any other type of disease. It is therefore particularly important to know whether alternative medicines (AMs) demonstrably generate more good than harm for such patients. Most alternative practitioners, of course, firmly believe in what they are doing. But what does the reliable evidence show?

To find out, ‘Arthritis Research UK’ has sponsored a massive project lasting several years to review the literature and critically evaluate the trial data. They convened a panel of experts (I was one of them) to evaluate all the clinical trials that are available in 4 specific clinical areas. The results for those forms of AM that are to be taken by mouth or applied topically have been published some time ago, now the report, especially written for lay people, on those treatments that are practitioner-based has been published. It covers the following 25 modalities:

Acupuncture

Alexander technique

Aromatherapy

Autogenic training

Biofeedback

Chiropractic (spinal manipulation)

Copper bracelets

Craniosacral therapy

Crystal healing

Feldenkrais

Kinesiology (applied kinesiology)

Healing therapies

Hypnotherapy

Imagery

Magnet therapy (static magnets)

Massage

Meditation

Music therapy

Osteopathy (spinal manipulation)

Qigong (internal qigong)

Reflexology

Relaxation therapy

Shiatsu

Tai chi

Yoga

Our findings are somewhat disappointing: only very few treatments were shown to be effective.

In the case of rheumatoid arthritis, 24 trials were included with a total of 1,500 patients. The totality of this evidence failed to provide convincing evidence that any form of AM is effective for this particular condition.

For osteoarthritis, 53 trials with a total of ~6,000 patients were available. They showed reasonably sound evidence only for two treatments: Tai chi and acupuncture.

Fifty trials were included with a total of ~3,000 patients suffering from fibromyalgia. The results provided weak evidence for Tai chi and relaxation-therapies, as well as more conclusive evidence for acupuncture and massage therapy.

Low back pain had attracted more research than any of the other diseases: 75 trials with ~11,600 patients. The evidence for Alexander Technique, osteopathy and relaxation therapies was promising by not ultimately convincing, and reasonably good evidence in support of yoga and acupuncture was also found.

The majority of the experts felt that the therapies in question did not frequently cause harm, but there were two important exceptions: osteopathy and chiropractic. For both, the report noted the existence of frequent yet mild, as well as serious but rare adverse effects.

As virtually all osteopaths and chiropractors earn their living by treating patients with musculoskeletal problems, the report comes as an embarrassment for these two professions. In particular, our conclusions about chiropractic were quite clear:

There are serious doubts as to whether chiropractic works for the conditions considered here: the trial evidence suggests that it’s not effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia and there’s only little evidence that it’s effective in osteoarthritis or chronic low back pain. There’s currently no evidence for rheumatoid arthritis.

Our point that chiropractic is not demonstrably effective for chronic back pain deserves some further comment, I think. It seems to be in contradiction to the guideline by NICE, as chiropractors will surely be quick to point out. How can this be?

One explanation is that, since the NICE-guidelines were drawn up, new evidence has emerged which was not positive. The recent Cochrane review, for instance, concludes that spinal manipulation “is no more effective for acute low-back pain than inert interventions, sham SMT or as adjunct therapy”

Another explanation could be that the experts on the panel writing the NICE-guideline were less than impartial towards chiropractic and thus arrived at false-positive or over-optimistic conclusions.

Chiropractors might say that my presence on the ‘Arthritis Research’-panel suggests that we were biased against chiropractic. If anything, the opposite is true: firstly, I am not even aware of having a bias against chiropractic, and no chiropractor has ever demonstrated otherwise; all I ever aim at( in my scientific publications) is to produce fair, unbiased but critical assessments of the existing evidence. Secondly, I was only one of a total of 9 panel members. As the following list shows, the panel included three experts in AM, and most sceptics would probably categorise two of them (Lewith and MacPherson) as being clearly pro-AM:

Professor Michael Doherty – professor of rheumatology, University of Nottingham

Professor Edzard Ernst – emeritus professor of complementary medicine, Peninsula Medical School

Margaret Fisken – patient representative, Aberdeenshire

Dr Gareth Jones (project lead) – senior lecturer in epidemiology, University of Aberdeen

Professor George Lewith – professor of health research, University of Southampton

Dr Hugh MacPherson – senior research fellow in health sciences, University of York

Professor Gary Macfarlane (chair of committee) – professor of epidemiology, University of Aberdeen

Professor Julius Sim – professor of health care research, Keele University

Jane Tadman – representative from Arthritis Research UK, Chesterfield

What can we conclude from all that? I think it is safe to say that the evidence for practitioner-based AMs as a treatment of the 4 named conditions is disappointing. In particular, chiropractic is not a demonstrably effective therapy for any of them. This, of course begs the question, for what condition is chiropractic proven to work! I am not aware of any, are you?