economic evaluation

THE SUN (…yes, I know! …) reported last Sunday that figures from 20 trusts show they forked out for questionable treatments for more than 3,000 patients. Treatments also including acupuncture and aromatherapy cost a total of £269,000. If the figure is applied across all 120-plus trusts the true cost could be well over £1.5 million. Hull University Teaching Hospitals spent the most, at £170,000.

The Taxpayers’ Alliance, which did the analysis, said: “With long waiting lists, quack remedies cannot be allowed to divert precious resources.” Alternative medicine expert Dr Edzard Ernst said: “The NHS often uses complementary medicine rarely based on good evidence but on lobbying of proponents of quackery.”

End of quote

Whenever I am asked by journalists to provide a critical comment on so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), I have mixed feelings. On the one hand, I find it important to get a rational message out, particularly into certain papers. On the other hand, I dread what they might do with my comment, particularly certain papers. If I had £5 for every time I have been misquoted, I could probably buy a decent second-hand car! This is why I nowadays tend to give my comments in writing via e-mail.

To my relief, THE SUN quoted me (almost) correctly. Almost correctly, but not fully! Here is the question I was asked to respond to: NHS statistics show the health service spending more than £250,000 on complementary and alternative medicines last year. Do you think this is a sensible use of NHS funding? Are the benefits well proven enough to spend taxpayer money on these therapies?

And here is my attempt to respond in a concise way that SUN readers might still understand:

Complementary medicine is an umbrella term for more than 400 treatments and diagnostic techniques. Some of them work but many don’t; some are safe but many are not. If the NHS would spend £250000 – a tiny amount considering the overall expenditure in the NHS – on those few that do generate more good than harm, all might be fine. The problem, I think, is that the NHS currently uses complementary medicine rarely based on good evidence but often based on the lobbying of influential proponents of quackery.

As you see, it is good to deal with requests from journalists in writing!

‘Chiropractic economics’ might be when chiropractors manipulate their bank accounts or tax returns, I thought. But, no, it is a publication! And a weird one at that – it even promotes the crazy idea of maintenance care:

The concept of chiropractic maintenance care has evolved significantly. Initially seen as a method for managing chronic pain, it now includes a broader range of patients and focuses on overall wellness. Modern maintenance care aims to keep patients healthy regardless of their symptoms or history, alleviating and preventing pain through regular, prolonged care. This approach is largely preventive, serving as both secondary and tertiary care. Studies show chiropractic maintenance care often includes diverse treatments such as manual therapy, stress management, nutrition advice and more, with flexible intervals typically around three months. This evolution underscores the importance of evidence-based, individualized patient care. This article shares the evolution of chiropractic maintenance care, looks at what a modern maintenance care appointment can include and explores best practices for DC maintenance care in 2024.

An interview study of Danish chiropractic care showed maintenance care sessions included a range of treatment modalities, including manual treatment and ordinary examinations alongside multiple packages of holistic additions, like stress management, diet, weight loss, advice on ergonomics, exercise and more. In other anecdotal accounts, chiropractic maintenance care seemed to follow a more traditional guideline of lower back pain management and adjustment. The study hypothesized that maintenance care could also help patients from a knowledge perspective, stating, “DCs could obviously play an important role here as ‘back pain coaches,’ as the long-term relationship would ensure knowledge of the patient and trust towards the DC.”

Researchers found that three-month intervals were the most common spacing of maintenance care treatments for patients. Most commonly, patients sought or scheduled chiropractic maintenance care over the course of one to three months.

Chiropractic maintenance care has evolved past simply being a method of ongoing chronic pain management. Today’s patients want to achieve overall wellness, and regular trips to their DC can become a part of that if you work to transition patients into a wellness plan after their acute phase of care is over.

_____________________________

The author of this article seems to have forgotten two little details:

- Chiropractic maintenance care is not supported by sound evidence, particularly in relation to economics (even the above cited paper stated: “We found no studies of cost-effectiveness of Maintenance Care”).

- Chiropractic maintenance only serves one economic purpose: it boosts the chiropractors’ income.

Yes, easy to forget, particularly if your name is ‘Chiropractic Economics’.

And also easy to forget that maintenance care would, of course, require informed consent. How would that look like?

Chiro (C) to patient (P):

If you agree, we will start a program that we call maintenance care.

P: Can you explain?

C: It consists of regular sessions of spinal manipulations.

P: That’s all?

C: No, I will also give you advice on keeping fit and living healthily.

P: Why do I need that?

C: It’s a bit like servicing your car so that it works reliably when you need it.

P: Is it proven to work?

C: Yes, of course, there are tons of evidence to show that a healthy life style is good for you.

P: I know, but I don’t need a chiro for that – what I meant do the manipulations keep my body healthy even if I have no symptoms?

C: The evidence is not really great.

P: And the risks?

C: Well, yes, if I’m honest, spinal manipulations can cause harm.

P: So, to be clear: you ask me to agree to a program that has no proven benefit and might cause harm?

C: I would not put it like that.

P: And how much would it cost?

C: Not much; just a couple of hundred per year.

P: Thanks – but no thanks.

In contemporary healthcare, evidence-based practices are fundamental for ensuring optimal patient outcomes and resource allocation. Essential steps for conducting pharmacoeconomic studies in homeopathy involve study design, intervention identification, comparator selection, outcome measures definition, data collection, cost analysis, effectiveness analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-benefit analysis, sensitivity analysis, reporting, and peer review. While conventional medicine undergoes rigorous pharmacoeconomic evaluations, the field of homeopathy often lacks such scrutiny. However, the importance of pharmacoeconomic studies in homeopathy is increasingly recognized, given its growing integration into modern healthcare systems.

A systematic review was aimed at summarizing the existing economic evaluations of homeopathy. It was conducted by searching electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science) to identify relevant literature using keywords such as “homeopathy,” “pharmacoeconomics,” and “efficacy.” Articles meeting inclusion criteria were assessed for quality using established frameworks like the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS). Data synthesis was conducted thematically, focusing on study objectives, methodologies, findings, and conclusions.

Ten pharmacoeconomic studies within homeopathy were identified, demonstrating varying degrees of compliance with reporting guidelines. While most studies reported costs comprehensively, some lacked methodological transparency, particularly in analytic methods. Heterogeneity was observed in study designs and outcome measures, reflecting the complexity of economic evaluation in homeopathy. Quality of evidence varied, with some studies exhibiting robust methodologies while others had limitations.

The authors concluded that, based on the review, recommendations include promoting homeopathic clinics, providing policy support, adopting collaborative healthcare models, and leveraging India’s homeopathic resources. Pharmacoeconomic studies in homeopathy are crucial for evaluating its economic implications compared to conventional medicine. While certain studies demonstrated methodological rigor, opportunities exist for enhancing consistency, transparency, and quality in economic evaluations. Addressing these challenges is essential for informing decision-making regarding the economic aspects of homeopathic interventions.

The truth is that there are not many economic studies of homeopathy that are worth the paper they were printed on. One of the most rigorous analysis was published by German pro-homeopathy researcher. This study aimed to provide a long-term cost comparison of patients using additional homeopathic treatment (homeopathy group) with patients using usual care (control group) over an observation period of 33 months.

Health claims data from a large statutory health insurance company were analysed from both the societal perspective (primary outcome) and from the statutory health insurance perspective (secondary outcome). To compare costs between patient groups, homeopathy and control patients were matched in a 1:1 ratio using propensity scores. Predictor variables for the propensity scores included health care costs and both medical and demographic variables. Health care costs were analysed using an analysis of covariance, adjusted for baseline costs, between groups both across diagnoses and for specific diagnoses over a period of 33 months. Specific diagnoses included depression, migraine, allergic rhinitis, asthma, atopic dermatitis, and headache.

Data from 21,939 patients in the homeopathy group (67.4% females) and 21,861 patients in the control group (67.2% females) were analysed. Health care costs over the 33 months were 12,414 EUR [95% CI 12,022-12,805] in the homeopathy group and 10,428 EUR [95% CI 10,036-10,820] in the control group (p<0.0001). The largest cost differences were attributed to productivity losses (homeopathy: EUR 6,289 [6,118-6,460]; control: EUR 5,498 [5,326-5,670], p<0.0001) and outpatient costs (homeopathy: EUR 1,794 [1,770-1,818]; control: EUR 1,438 [1,414-1,462], p<0.0001). Although the costs of the two groups converged over time, cost differences remained over the full 33 months. For all diagnoses, homeopathy patients generated higher costs than control patients.

The authors concluded that their analysis showed that even when following-up over 33 months, there were still cost differences between groups, with higher costs in the homeopathy group.

SURPRISE, SURPRISE!!!

Homeopathy is not cost-effective.

How could it possibly be? To be cost-effective, a theraapy has to be first of all effective – and that homeopathy is certainly not.

So, why does the avove-cited new paper arrive at a more positive conclusion?

Here are some potential explanations:

The authors of this paper are affiliated to:

- PatilTech Hom Research Solution, Maharashtra, India.

- Samarth Homeopathic Clinic and Research Center, Maharashtra, India.

The paper was published in the largely unknown, 3rd class Journal of Pharmacoeconomics and Pharmaceutical Management.

Most importantly, the authors aknowledge that many of the primary studies had serious methodological problems. However, this did not stop them from taking their data seriously. As a result, we have here another example of the old and well-known rule of systematic reviews:

RUBBISH IN, RUBBISH OUT!

To answer the question posed in the title of this post:

Is homeopathy cost-effective?

NO

This review updated and extended a previous one on the economic impact of homeopathy. A systematic literature search of the terms ‘cost’ and ‘homeopathy’ from January 2012 to July 2022 was performed in electronic databases. Two independent reviewers checked records, extracted data, and assessed study quality using the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list.

Six studies were added to 15 from the previous review. Synthesizing both health outcomes and costs showed homeopathic treatment being at least equally effective for less or similar costs than control in 14 of 21 studies. Three studies found improved outcomes at higher costs, two of which showed cost-effectiveness for homeopathy by incremental analysis. One found similar results and three similar outcomes at higher costs for homeopathy. CHEC values ranged between two and 16, with studies before 2009 having lower values (Mean ± SD: 6.7 ± 3.4) than newer studies (9.4 ± 4.3).

The authors concluded that, although results of the CHEC assessment show a positive chronological development, the favorable cost-effectiveness of homeopathic treatments seen in a small number of high-quality studies is undercut by too many examples of methodologically poor research.

I am always impressed by the fantastic and innovative phraseology that some authors are able to publish in order to avaid calling a spade a spade. The findings of the above analysis clearly fail to be positive. So why not say so? Why not honestly conclude something like this:

Our analysis failed to show conclusive evidence that homeopathy is cost effective.

To find an answer to this question, we need not look all that far. The authors’ affiliations give the game away:

- 1Department of Psychology and Psychotherapy, Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany.

- 2Medical Scientific Services/Medical Affairs, Deutsche Homöopathie-Union DHU-Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany.

- 3Institute of Integrative Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Herdecke, Germany.

- 4Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Another rather funny give-away is the title of the paper: the “…evaluation for…”comes form the authors’ original title (Overview and quality assessment of health economic evaluations for homeopathic therapy: an updated systematic review) and it implies an evaluation in favour of. The correct wording would be “evaluation of”, I think.

I rest my case.

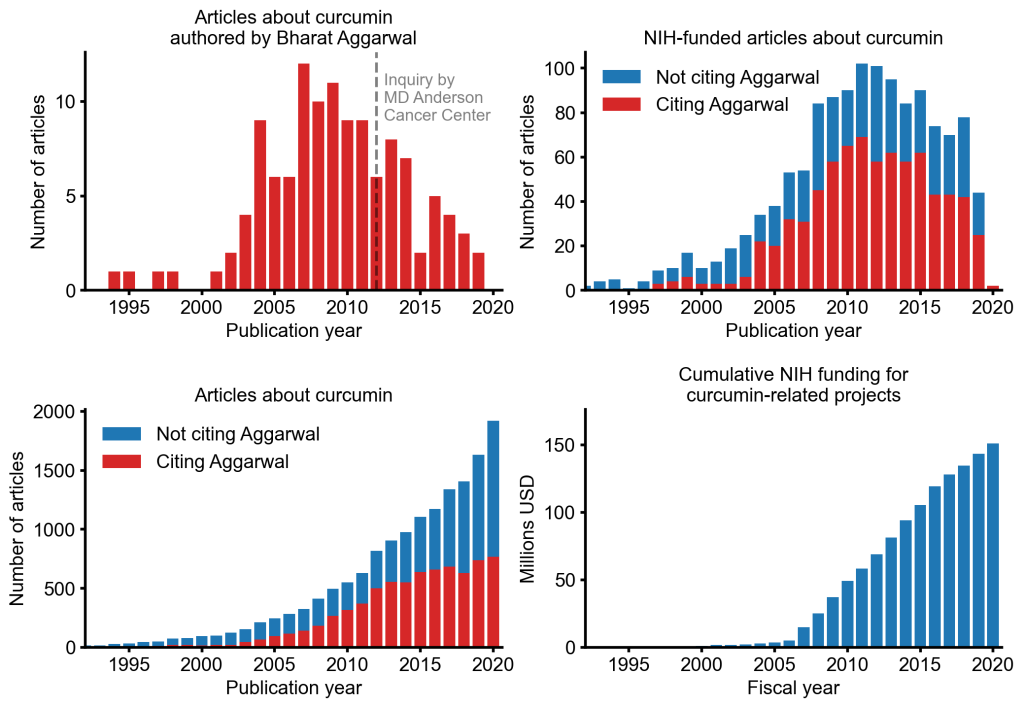

An alarming story of research fraud in the area of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) is unfolding: Bharat B. Aggarwal, the Indian-American biochemist who worked at MD Anderson Cancer Center, focused his research on curcumin, a compound found in turmeric, and authored more than 125 Medline-listed articles about it. They reported that curcumin had therapeutic potential for a variety of diseases, including various cancers, Alzheimer’s disease and, more recently, COVID-19.

The last of these papers, entitled “Curcumin, inflammation, and neurological disorders: How are they linked?”, was publiched only a few months ago. Here is its abstract:

Background: Despite the extensive research in recent years, the current treatment modalities for neurological disorders are suboptimal. Curcumin, a polyphenol found in Curcuma genus, has been shown to mitigate the pathophysiology and clinical sequalae involved in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases.

Methods: We searched PubMed database for relevant publications on curcumin and its uses in treating neurological diseases. We also reviewed relevant clinical trials which appeared on searching PubMed database using ‘Curcumin and clinical trials’.

Results: This review details the pleiotropic immunomodulatory functions and neuroprotective properties of curcumin, its derivatives and formulations in various preclinical and clinical investigations. The effects of curcumin on neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), brain tumors, epilepsy, Huntington’s disorder (HD), ischemia, Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and traumatic brain injury (TBI) with a major focus on associated signalling pathways have been thoroughly discussed.

Conclusion: This review demonstrates curcumin can suppress spinal neuroinflammation by modulating diverse astroglia mediated cascades, ensuring the treatment of neurological disorders.

The Anderson Cancer Center initially appeared to approve of Aggarwal’s work. However, in 2012, following concerns about image manipulation raised by pseudonymous sleuth Juuichi Jigen, MD Anderson Cancer Center launched a research fraud probe against Aggarwal which eventually led to 30 of Aggarwal’s articles being retracted. Moreover, PubPeer commenters have noted irregularities in many publications beyond the 30 that have already been retracted. Aggarwal thus retired from M.D. Anderson in 2015.

Curcumin doesn’t work well as a therapeutic agent for any disease – see, for instance, the summary from Nelson et al. 2017:

“[No] form of curcumin, or its closely related analogues, appears to possess the properties required for a good drug candidate (chemical stability, high water solubility, potent and selective target activity, high bioavailability, broad tissue distribution, stable metabolism, and low toxicity). The in vitro interference properties of curcumin do, however, offer many traps that can trick unprepared researchers into misinterpreting the results of their investigations.”

Despite curcumin’s apparent lack of therapeutic promise, the volume of research produced on curcumin grows each year. More than 2,000 studies involving the compound are now published annually. Many of these studies bear signs of fraud and involvement of paper mills. As of 2020, the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) has spent more than 150 million USD funding projects related to curcumin.

This proliferation of research has fueled curcumin’s popularity as a dietary supplement. It is estimated that the global market for curcumin as a supplement is around 30 million USD in 2020.

The damage done by this epic fraud is huge and far-reaching. Hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars, countless hours spent toiling by junior scientists, thousands of laboratory animals sacrificed, thousands of cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials for ineffective treatments, and countless people who have eschewed effective cancer treatment in favor of curcumin, were encouraged by research steeped in lies.

A ‘pragmatic, superiority, open-label, randomised controlled trial’ of sleep restriction therapy versus sleep hygiene has just been published in THE LANCET. Adults with insomnia disorder were recruited from 35 general practices across England and randomly assigned (1:1) using a web-based randomisation programme to either four sessions of nurse-delivered sleep restriction therapy plus a sleep hygiene booklet or a sleep hygiene booklet only. There was no restriction on usual care for either group. Outcomes were assessed at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. The primary endpoint was self-reported insomnia severity at 6 months measured with the insomnia severity index (ISI). The primary analysis included participants according to their allocated group and who contributed at least one outcome measurement. Cost-effectiveness was evaluated from the UK National Health Service and personal social services perspective and expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. The trial was prospectively registered (ISRCTN42499563).

Between Aug 29, 2018, and March 23, 2020 the researchers randomly assigned 642 participants to sleep restriction therapy (n=321) or sleep hygiene (n=321). Mean age was 55·4 years (range 19–88), with 489 (76·2%) participants being female and 153 (23·8%) being male. 580 (90·3%) participants provided data for at least one outcome measurement. At 6 months, mean ISI score was 10·9 (SD 5·5) for sleep restriction therapy and 13·9 (5·2) for sleep hygiene (adjusted mean difference –3·05, 95% CI –3·83 to –2·28; p<0·0001; Cohen’s d –0·74), indicating that participants in the sleep restriction therapy group reported lower insomnia severity than the sleep hygiene group. The incremental cost per QALY gained was £2076, giving a 95·3% probability that treatment was cost-effective at a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000. Eight participants in each group had serious adverse events, none of which were judged to be related to intervention.

The authors concluded that brief nurse-delivered sleep restriction therapy in primary care reduces insomnia symptoms, is likely to be cost-effective, and has the potential to be widely implemented as a first-line treatment for insomnia disorder.

I am frankly amazed that this paper was published in a top journal, like THE LANCET. Let me explain why:

The verum treatment was delivered over four consecutive weeks, involving one brief session per week (two in-person sessions and two sessions over the phone). Session 1 introduced the rationale for sleep restriction therapy alongside a review of sleep diaries, helped participants to select bed and rise times, advised on management of daytime sleepiness (including implications for driving), and discussed barriers to and facilitators of implementation. Session 2, session 3, and session 4 involved reviewing progress, discussion of difficulties with implementation, and titration of the sleep schedule according to a sleep efficiency algorithm.

This means that the verum group received fairly extensive attention, while the control group did not. In other words, a host of non-specific effects are likely to have significantly influenced or even entirely determined the outcome. Despite this rather obvious limitation, the authors fail to discuss any of it. On the contrary, that claim that “we did a definitive test of whether brief sleep restriction therapy delivered in primary care is clinically effective and cost-effective.” This is, in my view, highly misleading and unworthy of THE LANCET. I suggest the conclusions of this trial should be re-formulated as follows:

The brief nurse-delivered sleep restriction, or the additional attention provided exclusively to the patients in the verum group, or a placebo-effect or some other non-specific effect reduced insomnia symptoms.

Alternatively, one could just conclude from this study that poor science can make it even into the best medical journals – a problem only too well known in the realm of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services alleges that Jason James of the James Healthcare & Associates clinic in Iowa, USA — along with his wife, Deanna James, the clinic’s co-owner and office manager — filed dozens of claims with Medicare for a disposable acupuncture device, which is not covered by Medicare, as if it were a surgically implanted device for which Medicare can be billed. According to the lawsuit, more than 180 such claims were filed. Beginning in 2016, the lawsuit alleges, the clinic began offering an electro-acupuncture device referred to as a “P-Stim.” When used as designed, the P-Stim device is affixed behind a patient’s ear using an adhesive. The device delivers intermittent electrical pulses through a single-use, battery-powered attachment for several days until the battery runs out and the device is thrown away.

Because Medicare does not reimburse medical providers for the use of such devices, DHHS alleges that some doctors and clinics have billed Medicare for the P-Stim device using a code number that only applies to a surgically implanted neurostimulator. The use of an actual neurostimulator is reimbursed by Medicare at approximately $6,000 per claim, while P-Stim devices were purchased by the Keokuk clinic for just $667, DHHS alleges. The department alleges James knew his billings were fraudulent as the P-Stim device is “nowhere close to even resembling genuine implantable neurostimulators” and does not require surgery.

The lawsuit alleges that on June 15, 2016, when Jason James was contemplating the use of P-Stim devices at the Keokuk clinic, he sent a text message to P-Stim sales representative Mark Kaiser, asking, “Is there a limit on how many Neurostims can be done on one day? Don’t wanna do so many that gives Medicare a red flag on first day. Thanks.” After realizing the “large profit windfall” that could result from the billing practice, DHHS’s lawsuit alleges, James “told Mark Kaiser not to mention the Medicare reimbursement rate to his nurse practitioner or staff – only his office manager and biller needed that information.” James then pressured clinic employees to heavily market the P-Stim devices to patients, even if those patients were not agreeable or, after trying it, were reluctant to continue the treatment, the lawsuit claims.

In October 2016, the clinic’s supplier of P-Stim devices sent the clinic an email stating the company had “no position on what the proper coding might be for this device if billed to a third-party payer” such as an insurer or Medicare, according to the lawsuit. The company advised the clinic to “consult a certified biller/coder and/or attorney to ensure compliance.” According to the lawsuit, James then sent Kaiser a text message asking, “Should we be concerned?”

DHHS alleges the clinic’s initial reimbursement claims were submitted to Medicare through a nurse practitioner and were denied for payment due to the lack of a trained physician’s involvement. In response, the clinic hired Dr. Robert Schneider, an Iowa-licensed physician, to work at the clinic for the sole purpose of enabling James Healthcare & Associates to bill Medicare for the P-Stim devices, the lawsuit claims. James then informed Kaiser he had a goal of billing Medicare for 20 devices per month, which would generate roughly $125,573 of monthly income, the lawsuit alleges. The lawsuit also alleges Dr. Schneider rarely saw clinic patients in person, consulting with them instead through Facebook Live.

In April 2017, Medicare allegedly initiated a review of the clinic’s medical records, triggering additional communications between James and Kaiser. At one point, James allegedly wrote to Kaiser and said he had figured out why Medicare was auditing the clinic. “Anything over $7,500 is automatically audited for my area,” he wrote, according to the lawsuit. “We are now charging $7,450 to remove the audit.”

The clinic ultimately submitted 188 false claims to Medicare seeking reimbursement for the P-Stim devices, DHHS alleges, with Medicare paying out $4,100 and $6,300 per claim, for a total loss of $1,028,800. DHHS is suing the clinic under the federal False Claims Act and is seeking trebled damages of more than $3 million, plus a civil penalty of up to $4.2 million.

An attorney for the clinic, Michael Khouri, said Wednesday he believe the federal government’s lawsuit was filed in error because a settlement in the case had already been reached. However, the assistant U.S. attorney handling the case said no settlement in the case had been finalized and the lawsuit was not filed in error.

Previous legal cases

In 2015, the Iowa Board of Chiropractic charged Jason James with knowingly making fraudulent or untrue representations in connection with his practice, engaging in conduct that was harmful or detrimental to the public, and making untruthful statements in advertising. The board alleged James told patients they would be able to stop taking diabetes medication through the use of a diet and nutrition program, and that he had claimed to be providing extensive laboratory tests when not all of the tests for which he billed were ever conducted. The board also claimed James referred patients to a medical professional who was not licensed to practice in Iowa. The case was resolved with a settlement agreement in which James agreed to pay a $500 penalty and complete 10 hours of education in marketing and ethics.

In 2019, Schneider sued the clinic for failing to comply with the terms of his employment agreement. Court exhibits indicate the agreement stipulated that Schneider was to work no more than two days per month and would collect $2,000 for each day worked, plus $250 per month for consulting, plus “$250 per device over six per calendar month.” In March 2020, a jury ruled in favor of the clinic and found that it had not breached its employment agreement with Schneider.

_________________________

Before some chiropractors now claim that such cases represent just a few rotten apples in a big basket of essentially honest chiropractors, let me remind them of a few previous posts:

- A $2.6M Insurance Fraud by Chiropractors and Doctors?

- Fraud and sex offences by chiropractors

- Chiropractic therapy for gastrointestinal diseases. Evidence of scientific misconduct?

- Twenty Things Most Chiropractors Won’t Tell You

- The Dark Side of Chiropractic Care

- Chiropractic subluxation: the myth must be kept alive

- CHIROPRACTIC: an early and delightful critique

- Students of chiropractic condemn the ‘unacceptable behaviour’ of some chiropractors and their professional organisations

- Far too many chiropractors believe that vaccinations do not have a positive effect on public health

- Chiropractor is in the dock for not wearing a mask

- “The uncensored truth” about COVID-19 vaccines” … as told by some chiro loons

To put it bluntly: chiropractic was founded by a crook on a bunch of lies and unethical behavior, so it is hardly surprising that today the profession has a problem with ethics and honesty.

In the UK – this post is mainly for UK readers – journalists and opinion leaders are currently falling over themselves reporting about a major breakthrough: an Alzheimer’s drug has been shown to slow the disease by around 36%. “After 20 years with no new Alzheimer’s disease drugs in the UK, we now have two potential new drugs in 12 just months,” wrote Dr Richard Oakley, associate director at the Alzheimer’s Society. And the Daily Mail headlined: “New drug which claims to slow mental decline caused by Alzheimer’s by 36% could spell ‘the beginning of the end’ for the degenerative brain disease”.

That’s excellent news!

Many people will have made a sigh of relief!

So, why does it make me angry?

Once we listen to the news more closely we learn that:

- the drug only works for patients who are diagnosed early;

- for an early diagnosis, we need a PET scan;

- the UK hardly has any PET scanners, in fact, we have the lowest number among developed countries;

- these scanners are very expensive;

- the costs for the new drug are as yet unknown but will also be high.

Collectively these facts mean that we have a major advance in healthcare that could help many patients. At the same time, we all know that this is mere theory and that the practice will be very different.

Why?

- Because the NHS has been run down and is on its knees.

- Because our government will again say that they have invested xy millions into this area.

- The statement might be true or not, but in any case, the funds will be far too little.

- The UK has become a country where some patients suffering from severe toothache currently resort to pulling out their own teeth at home with pairs of pliers.

- In the foreseeable future, the NHS will not be allocated the money to invest in sufficient numbers of PET scans (not to mention the funds to buy the new and expensive drug).

In other words, the UK celebrates yet another medical advance raising many people’s expectations, while everyone in the know is well aware of the fact that the UK public will not benefit from it.

Does that not make you angry too?

Yesterday, the NHS turned 75, and virtually all the newspapers have joined in the chorus singing its praise.

RIGHTLY SO!

The idea of nationalized healthcare free for all at the point of delivery is undoubtedly a good one. I’d even say that, for a civilized country, it is an essential concept. The notion that an individual who had the misfortune to fall ill might have to ruin his/her livelihood to get treated is absurd and obscene to me.

The NHS was created the same year that I was born. Even though I did not grow up in the UK, I cannot imagine a healthcare system where people have to pay to get or stay healthy. To me, ‘free’ – it is, of course not free at all but merely free at the point of delivery – is a human right just as freedom of speech or the right to a good education.

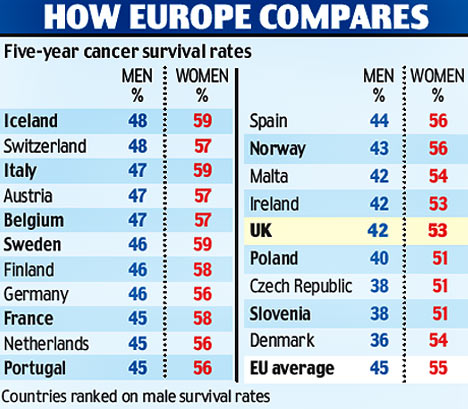

While reading some of what has been written about the NHS’s 75th birthday, I came across more platitudes than I care to remember. Yes, we are all ever so proud of the NHS but we would be even more proud if our NHS did work adequately. I find it somewhat hypocritical to sing the praise of a system that is clearly not functioning nearly as well as that of comparable European countries (where patients also don’t have to pay out of their own pocket for healthcare). I also find it sickening to listen to politicians paying lip service, while doing little to fundamentally change things. And I find it enraging to see how the conservatives have systematically under-funded the NHS, while pretending to support it adequately.

While reading some of what has been written about the NHS’s 75th birthday, I came across more platitudes than I care to remember. Yes, we are all ever so proud of the NHS but we would be even more proud if our NHS did work adequately. I find it somewhat hypocritical to sing the praise of a system that is clearly not functioning nearly as well as that of comparable European countries (where patients also don’t have to pay out of their own pocket for healthcare). I also find it sickening to listen to politicians paying lip service, while doing little to fundamentally change things. And I find it enraging to see how the conservatives have systematically under-funded the NHS, while pretending to support it adequately.

How can we be truly proud of the NHS when it seems to be dying a slow and agonizing death due to political neglect? In the UK, politicians like to be ‘world beating’ with everything, and I am sure some Tories want you to believe that, under their leadership, a world-beating healthcare system has been established in the UK.

Let me tell you: it’s not true. I have personal experience with the healthcare systems of 5 different nations and worked as a doctor in 3 of them. In Austria, France, and Germany for instance, the system is significantly better and no patient’s finances are ruined through illness.

Now there is talk about reform – yet again! Let us please not look towards the US when thinking of reforming the NHS. I have lived for a while in America and can tell you one thing: when it comes to healthcare, the US is not a civilized country. If reform of the NHS is again on the cards, let us please look towards the more civilized parts of the world!

Exceptionally, this post is unrelated to so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). It addresses a new and worrisome development in UK healthcare. The UK has fewer doctors per population than most other developed countries. This shortage has now reached a level where it puts patients in danger. Recently, the government has unveiled a new NHS plan aimed to fix the problem.

The apprenticeship scheme could allow one in 10 doctors to start work without a traditional medical degree, straight after their A-levels. A third of nurses are also expected to be trained under the “radical new approach”. It is the centerpiece of a long-delayed NHS workforce strategy, following warnings that staff shortages in England could reach half a million without action to find new ways to train and recruit health workers. Amanda Pritchard, the head of NHS England, said: “This radical new approach could see tens of thousands of school-leavers becoming doctors and nurses or other key healthcare roles, after being trained on the job over the next 25 years.” She added that the plan offered a “once-in-a-generation opportunity to put the NHS on a sustainable footing”.

The “medical doctor degree apprenticeship” involves the same training and standards as traditional education routes, including a medical degree and all the requirements of the General Medical Council. Candidates will be expected to have similar A-levels as those for medical school, with qualifications in sciences, as well as options for graduates with non-medical degrees. The key difference behind such models is that apprentice medics would be available on the wards almost immediately, working under supervision, while being paid.

The medical degree apprenticeship is due to launch this autumn.

_______________________________

I am impressed!

Sadly, not in a positive way.

In fact, I cannot remember having ever heard of a more stupid idea for dealing with doctor shortages.

As incompetent amateurs, do the Tories really think that a similar level of incompetence might work also in healthcare?

Such shortages have happened before.

They are regrettable and need swift and firm action.

The only countermeasure that works is to train more doctors.

REAL DOCTORS!