kinesiology

Osteopathy is currently regulated in 12 European countries: Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Iceland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Switzerland, and the UK. Other countries such as Belgium and Norway have not fully regulated it. In Austria, osteopathy is not recognized or regulated. The Osteopathic Practitioners Estimates and RAtes (OPERA) project was developed as a Europe-based survey, whereby an updated profile of osteopaths not only provides new data for Austria but also allows comparisons with other European countries.

A voluntary, online-based, closed-ended survey was distributed across Austria in the period between April and August 2020. The original English OPERA questionnaire, composed of 52 questions in seven sections, was translated into German and adapted to the Austrian situation. Recruitment was performed through social media and an e-based campaign.

The survey was completed by 338 individuals (response rate ~26%), of which 239 (71%) were female. The median age of the responders was 40–49 years. Almost all had preliminary healthcare training, mainly in physiotherapy (72%). The majority of respondents were self-employed (88%) and working as sole practitioners (54%). The median number of consultations per week was 21–25 and the majority of respondents scheduled 46–60 minutes for each consultation (69%).

The most commonly used diagnostic techniques were: palpation of position/structure, palpation of tenderness, and visual inspection. The most commonly used treatment techniques were cranial, visceral, and articulatory/mobilization techniques. The majority of patients estimated by respondents consulted an osteopath for musculoskeletal complaints mainly localized in the lumbar and cervical region. Although the majority of respondents experienced a strong osteopathic identity, only a small proportion (17%) advertise themselves exclusively as osteopaths.

The authors concluded that this study represents the first published document to determine the characteristics of the osteopathic practitioners in Austria using large, national data. It provides new information on where, how, and by whom osteopathic care is delivered. The information provided may contribute to the evidence used by stakeholders and policy makers for the future regulation of the profession in Austria.

This paper reveals several findings that are, I think, noteworthy:

- Visceral osteopathy was used often or very often by 84% of the osteopaths.

- Muscle energy techniques were used often or very often by 53% of the osteopaths.

- Techniques applied to the breasts were used by 59% of the osteopaths.

- Vaginal techniques were used by 49% of the osteopaths.

- Rectal techniques were used by 39% of the osteopaths.

- “Taping/kinesiology tape” was used by 40% of osteopaths.

- Applied kinesiology was used by 17% of osteopaths and was by far the most-used diagnostic approach.

Perhaps the most worrying finding of the entire paper is summarized in this sentence: “Informed consent for oral techniques was requested only by 10.4% of respondents, and for genital and rectal techniques by 21.0% and 18.3% respectively.”

I am lost for words!

I fail to understand what meaningful medical purpose the fingers of an osteopath are supposed to have in a patient’s vagina or rectum. Surely, putting them there is a gross violation of medical ethics.

Considering these points, I find it impossible not to conclude that far too many Austrian osteopaths practice treatments that are implausible, unproven, potentially harmful, unethical, and illegal. If patients had the courage to take action, many of these charlatans would probably spend some time in jail.

My new book has just been published. Allow me to try and whet your appetite by showing you the book’s introduction:

“There is no alternative medicine. There is only scientifically proven, evidence-based medicine supported by solid data or unproven medicine, for which scientific evidence is lacking.” These words of Fontanarosa and Lundberg were published 22 years ago.[1] Today, they are as relevant as ever, particularly to the type of healthcare I often call ‘so-called alternative medicine’ (SCAM)[2], and they certainly are relevant to chiropractic.

“There is no alternative medicine. There is only scientifically proven, evidence-based medicine supported by solid data or unproven medicine, for which scientific evidence is lacking.” These words of Fontanarosa and Lundberg were published 22 years ago.[1] Today, they are as relevant as ever, particularly to the type of healthcare I often call ‘so-called alternative medicine’ (SCAM)[2], and they certainly are relevant to chiropractic.

Invented more than 120 years ago by the magnetic healer DD Palmer, chiropractic has had a colourful history. It has now grown into one of the most popular of all SCAMs. Its general acceptance might give the impression that chiropractic, the art of adjusting by hand all subluxations of the three hundred articulations of the human skeletal frame[3], is solidly based on evidence. It is therefore easy to forget that a plethora of fundamental questions about chiropractic remain unanswered.

I wrote this book because I feel that the amount of misinformation on chiropractic is scandalous and demands a critical evaluation of the evidence. The book deals with many questions that consumers often ask:

- How well-established is chiropractic?

- What treatments do chiropractors use?

- What conditions do they treat?

- What claims do they make?

- Are their assumptions reasonable?

- Are chiropractic spinal manipulations effective?

- Are these manipulations safe?

- Do chiropractors behave professionally and ethically?

Am I up to this task, and can you trust my assessments? These are justified questions; let me try to answer them by giving you a brief summary of my professional background.

I grew up in Germany where SCAM is hugely popular. I studied medicine and, as a young doctor, was enthusiastic about SCAM. After several years in basic research, I returned to clinical medicine, became professor of rehabilitation medicine first in Hanover, Germany, and then in Vienna, Austria. In 1993, I was appointed as Chair in Complementary Medicine at the University of Exeter. In this capacity, I built up a multidisciplinary team of scientists conducting research into all sorts of SCAM with one focus on chiropractic. I retired in 2012 and am now an emeritus professor. I have published many peer-reviewed articles on the subject, and I have no conflicts of interest. If my long career has taught me anything, it is this: in the best interest of consumers and patients, we must insist on sound evidence; not opinion, not wishful thinking; evidence.

In critically assessing the issues related to chiropractic, I am guided by the most reliable and up-to-date scientific evidence. The conclusions I reach often suggest that chiropractic is not what it is often cracked up to be. Hundreds of books have been published that disagree. If you are in doubt who to trust, the promoter or the critic of chiropractic, I suggest you ask yourself a simple question: who is more likely to provide impartial information, the chiropractor who makes a living by his trade, or the academic who has researched the subject for the last 30 years?

This book offers an easy to understand, concise and dependable evaluation of chiropractic. It enables you to make up your own mind. I want you to take therapeutic decisions that are reasonable and based on solid evidence. My book should empower you to do just that.

[1] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9820267

[2] https://www.amazon.co.uk/SCAM-So-Called-Alternative-Medicine-Societas/dp/1845409701/ref=pd_rhf_dp_p_img_2?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=449PJJDXNTY60Y418S5J

[3] https://www.amazon.co.uk/Text-Book-Philosophy-Chiropractic-Chiropractors-Adjuster/dp/1635617243/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=DD+Palmer&qid=1581002156&sr=8-1

Chiropractic is hugely popular, we are often told. The fallacious implication is, of course, that popularity can serve as a surrogate measure for effectiveness. In the United States, chiropractors provided 18.6 million clinical services under Medicare in 2015, and overall spending for chiropractic services was estimated at USD $12.5 billion. Elsewhere, chiropractic seems to be less commonly used, and the global situation has not recently been outlined. The authors of this ‘global overview‘ might fill this gap by summarizing the current literature on the utilization of chiropractic services, reasons for seeking care, patient profiles, and assessment and treatment provided.

Systematic searches were conducted in MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Index to Chiropractic Literature from database inception to January 2016. Eligible articles

1) were published in English or French (not all that global then!);

2) were case series, descriptive, cross-sectional, or cohort studies;

3) described patients receiving chiropractic services;

4) reported on the following theme(s): utilization rates of chiropractic services; reasons for attending chiropractic care; profiles of chiropractic patients; or, types of chiropractic services provided.

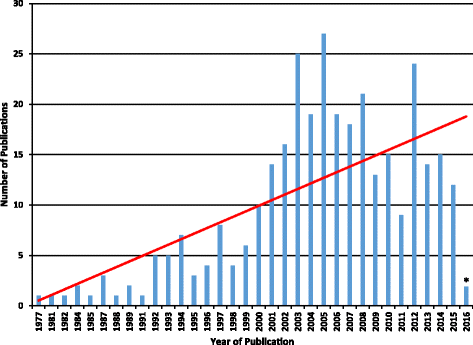

The literature searches retrieved 328 studies (reported in 337 articles) that reported on chiropractic utilization (245 studies), reason for attending chiropractic care (85 studies), patient demographics (130 studies), and assessment and treatment provided (34 studies).

Globally, the median 12-month utilization of chiropractic services was 9.1% (interquartile range (IQR): 6.7%-13.1%) and remained stable between 1980 and 2015. Most patients consulting chiropractors were female (57.0%, IQR: 53.2%-60.0%) with a median age of 43.4 years (IQR: 39.6-48.0), and were employed.

The most common reported reasons for people attending chiropractic care were (median) low back pain (49.7%, IQR: 43.0%-60.2%), neck pain (22.5%, IQR: 16.3%-24.5%), and extremity problems (10.0%, IQR: 4.3%-22.0%). The most common treatment provided by chiropractors included (median) spinal manipulation (79.3%, IQR: 55.4%-91.3%), soft-tissue therapy (35.1%, IQR: 16.5%-52.0%), and formal patient education (31.3%, IQR: 22.6%-65.0%).

The authors concluded that this comprehensive overview on the world-wide state of the chiropractic profession documented trends in the literature over the last four decades. The findings support the diverse nature of chiropractic practice, although common trends emerged.

My interpretation of the data presented is somewhat different from that of the authors. For instance, I fail to share the notion that utilization remained stable over time.

The figure might not be totally conclusive, but I seem to detect a peak in 2005, followed by a decline. Also, as the vast majority of studies originate from the US, I find it difficult to conclude anything about global trends in utilization.

Some of the more remarkable findings of this paper include the fact that 3.1% (IQR: 1.6%-6.1%) of the general population sought chiropractic care for visceral/non-musculoskeletal conditions. Some of the reasons for attending chiropractic care reported by the paediatric population are equally noteworthy: 7% for infections, 5% for asthma, and 5% for stomach problems. Globally, 5% of all consultations were for wellness/maintenance. None of these indications is even remotely evidence-based, of course.

Remarkably, 35% of chiropractors used X-ray diagnostics, and only 31% did a full history of their patients. Spinal manipulation was used by 79%, 31% sold nutritional supplements to their patients, and 10% used applied kinesiology.

In general, this is an informative paper. However, it suffers from a distinct lack of critical input. It seems to skip over almost all areas that might be less than favourable for chiropractors. The reason for this becomes clear, I think, when we read the source of funding for the research: PJHB, AEB, SAM and SDF have received research funding from the Canadian national and provincial chiropractic organizations, either as salary support or for research project funding. JJW received research project funding from the Ontario Chiropractic Association, outside the submitted work. SDF is Deputy Editor-in-Chief for Chiropractic and Manual Therapies; however, he did not have any involvement in the editorial process for this manuscript and was blinded from the editorial system for this paper from submission to decision.

An article by Rabbi Yair Hoffman for the Five Towns Jewish Times caught my eye. Here are a few excerpts:

“I am sorry, Mrs. Ploni, but the muscle testing we performed on you indicates that your compatibility with your spouse is a 1 out of a possible 10 on the scale.”

“Your son being around his father is bad for his energy levels. You should seek to minimize it.”

“Your husband was born normal, but something happened to his energy levels on account of the vaccinations he received as a child. It is not really his fault, but he is not good for you.”

Welcome to the world of Applied Kinesiology (AK) or health Kinesiology… Incredibly, there are people who now base most of their life decisions on something called “muscle testing.” Practitioners believe or state that the body’s energy levels can reveal remarkable information, from when a bride should get married to whether the next Kinesiology appointment should be in one week or two weeks. Prices for a 45 minute appointment can range from $125 to $250 a session. One doctor who is familiar with people who engage in such pursuits remarked, “You have no idea how many inroads this craziness has made in our community.”

… AK (applied kinesiology) is system that evaluates structural, chemical, and mental aspects of health by using “manual muscle testing (MMT)” along with other conventional diagnostic methods. The belief of AK adherents is that every organ dysfunction is accompanied by a weakness in a specific corresponding muscle… Treatments include joint manipulation and mobilization, myofascial, cranial and meridian therapies, clinical nutrition, and dietary counselling. A manual muscle test is conducted by having the patient resist using the target muscle or muscle group while the practitioner applies force the other way. A smooth response is called a “strong muscle” and a response that was not appropriate is called a “weak response.” Like some Ouiji board out of the 1970’s, Applied Kinesiology is used to ask “Yes or No” questions about issues ranging from what type of Parnassa courses one should be taking, to what Torah music tapes one should listen to, to whether a therapist is worthwhile to see or not.

“They take everything with such seriousness – they look at it as if it is Torah from Sinai,” remarked one person familiar with such patients. One spouse of an AK patient was shocked to hear that a diagnosis was made concerning himself through the muscle testing of his wife – without the practitioner having ever met him… And the lines at the office of the AK practitioner are long. One husband holds a crying baby for three hours, while his wife attends a 45 minute session. Why so long? The AK practitioner let other patients ahead – because of emergency needs…

END OF EXCERPTS

The article is a reminder how much nonsense happens in the name of alternative medicine. AK is one of the modalities that is exemplary:

- it is utterly implausible;

- there is no good evidence that it works.

The only systematic review of AK was published in 2008 by a team known to be strongly in favour of alternative medicine. It included 22 relevant studies. Their methodology was poor. The authors concluded that there is insufficient evidence for diagnostic accuracy within kinesiology, the validity of muscle response and the effectiveness of kinesiology for any condition.

Some AK fans might now say: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence!!! There is no evidence that AK does not work, and therefore we should give it the benefit of the doubt and use it.

This, of course, is absolute BS! Firstly, the onus is on those who claim that AK works to prove their assumption. Secondly, in responsible healthcare, we are obliged to employ those modalities for which the evidence is positive, while avoiding those for which the evidence fails to be positive.

The ‘CHRONICLE OF CHIROPRACTIC’ recently reported on the relentless battle within the chiropractic profession about the issue of ‘subluxation’. Here is (slightly abbreviated) what this publication had to say:

START OF QUOTE

Calling subluxation based chiropractors “unacceptable creatures” chiropractic researcher Keith H Charlton DC, MPhil, MPainMed, PhD, FICC, recently stated “. . . that it is no longer scientifically acceptable for any responsible chiropractic clinician to ever use the word subluxation except as theory . . .” Charlton made the comment to members of the Chiropractic Research Alliance a group of subluxation deniers who routinely disparage the concept of subluxation.

Charlton is a well known “Subluxation Denier” and frequently attacks subluxation based chiropractors in his peer reviewed research papers and on Facebook groups. According to Charlton in a paper published in the journal Chiropractic and Osteopathy: “The dogma of subluxation is perhaps the greatest single barrier to professional development for chiropractors. It skews the practice of the art in directions that bring ridicule from the scientific community and uncertainty among the public.”

On January 5, 2017 Charlton further stated: “We need NOW in 2017 and beyond to get rid of the quacks that do us so much harm. They need to be treated personally and professionally as utterly unacceptable creatures to be shunned and opposed at every turn. Time to get going on cleaning out the trash. And that includes all signs, websites, literature, handouts and speech of staff and chiropractors.”

…Charlton has testified against subluxation based chiropractors in regulatory board actions and appears to revel in it.

In his most recent pronouncement Charlton states that he is okay with subluxation as a “regional spine shape distortion” and asserts that this is a CBP subluxation. This contention is common with subluxation deniers who are willing to accept an orthopedic definition of subluxation absent the neurological component.

…Charlton states he uses the following techniques on his website:

- Applied Kinesiology

- Diversified

- Motion Palpation

- Sacro-Occipital Technique

- Activator

- Logan Basic

When this self-declared scientist was confronted with his use of Applied Kinesiology and these other techniques his response was essentially that he is engaging in a “bait and switch” and that he just has those on his website to get patients who are looking for those things. Charlton lists 21 “research papers” on his curriculum vitae though they are all simply commentaries or reviews not original clinical research. The majority of these opinion pieces are attacks on subluxation and the chiropractors who focus on it.

END OF QUOTE

What does this tell us?

- It seems to me that the ‘anti-subluxation’ movement with in the chiropractic profession is by no means winning the battle against the ‘hard-core subluxationists’.

- Chiropractors cannot resist the temptation to use ad hominem attacks instead of factual arguments. I suppose this is because the latter are in short supply.

- The ‘anti-subluxationists’ present themselves as the evidence-based side of the chiropractic spectrum. This impression might well be erroneous. Giving up the myth of subluxation obviously does not necessarily mean abandoning other forms of quackery.

Researchers from the ‘Complementary and Integrative Medicine Research, Primary Medical Care, University of Southampton’ conducted a study of Professional Kinesiology Practice (PKP) What? Yes, PKP! This is a not widely known alternative method.

According to its proponents, it is unique and a complete kinesiology system… It was developed by a medical doctor, Dr Bruce Dewe and his wife Joan Dewe in the 1980s and has been taught since then in over 16 countries around the world with great success… Kinesiology is a unique and truly holistic science and on the cutting edge of energy medicine. It uses muscle monitoring as a biofeedback system to identify the underlying cause of blockage from the person’s subconscious mind via the nervous system. Muscle monitoring is used to access information from the person’s “biocomputer”, the brain, in relation to the problem or issue and also guides the practitioner to find the priority correction in order to stimulate the person’s innate healing capacity and support their physiology to return to normal function. Kinesiology is unique as it looks beyond symptoms. It recognizes the flows of energy within the body not only relate to the muscles but to every tissue and organ that make the human body a living ever changing organism. These energy flows can be evaluated by testing the function of the muscles, which in turn reflect the body’s overall state of structural, chemical, emotional and spiritual balance. In this way kinesiology taps into energies that the more conventional modalities overlook and helps remove all the guesswork, doubt and hard work of subjective diagnostics. This is a revolutionary way to communicate with the body/mind connection. Through muscle monitoring and the use of over 300 fingermodes we can detect and correct the cause of the problem and effect a long lasting change for better health and wellbeing. Our posture could be considered to be the visual display unit from our internal bio-computer. Our posture / life energy improves as we upgrade the way we respond to life’s constant challenges and demands.

You do not understand? Let me make it crystal clear by citing another PKP-site:

PKP is a phenomenological practice – this means practitioners use manual muscle testing to demonstrate to the client how much or how little they are able to move in relation to their problem. PKP practitioners have tests for more than 100 muscles, and dozens of other tests that they do so they can clearly show you how your movement is affected by your problem. This muscle story shows a person how their life is unfolding, and it also helps to guide on how to transcend the situation and design a future which is more in alignment with nature and the laws of the cosmos… PKP is about living life more wisely.

In case you still have not understood what PKP is, you might have to watch this youtube clip. And now that everyone knows what it is, let us have a look at the new study.

According to its authors, it was an exploratory, pragmatic single-blind, 3-arm randomised sham-controlled pilot trial with waiting list control (WLC) which was conducted in the setting of a UK private practice. Seventy participants scoring ≥4 on the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) were randomised to real or sham PKP receiving one treatment weekly for 5 weeks or a WLC. WLC’s were re-randomised to real or sham after 6 weeks. The main outcome measure was a change in RMDQ from baseline to end of 5 weeks of real or sham PKP.

The results show an effect size of 0.7 for real PKP which was significantly different to sham. Compared to WLC, both real and sham groups had significant RMDQ improvements. Practitioner empathy (CARE) and patient enablement (PEI) did not predict outcome; holistic health beliefs (CAMBI) did, though. The sham treatment appeared credible; patients did not guess treatment allocation. Three patients reported minor adverse reactions.

From these data, the authors conclude that real treatment was significantly different from sham demonstrating a moderate specific effect of PKP; both were better than WLC indicating a substantial non-specific and contextual treatment effect. A larger definitive study would be appropriate with nested qualitative work to help understand the mechanisms involved in PKP.

So, PKP has a small specific effect in addition to generating a sizable placebo-effect? Somehow, I doubt it! This was, according to its authors, a pilot study. Such an investigation should not evaluate the effectiveness of a treatment but the feasibility of the protocol. Even if we disregard this detail, I assume that the results indicate the effects of PKP to be essentially due to placebo. The small effect which the authors label as “specific” is, in my view, almost certainly caused by residual confounding and hidden biases.

One could also go one step further and say that any treatment that is shrouded in pseudo-scientific language and has zero plausibility is an ill-conceived candidate for a clinical trial of this nature. If it should be tested at all – and thus cost money, effort and patient-participation – a rigorous study should be designed and conducted not by apologists of the intervention but by more level-headed scientists.