acupressure

Whenever a journalist wants to discuss the subject of acupuncture with me, he or she will inevitably ask one question:

DOES ACUPUNCTURE WORK?

It seems a legitimate, obvious and simple question, particularly during ‘Acupuncture Awareness Week‘, and I have heard it hundreds of times. Why then do I hesitate to answer it?

Journalists – like most of us – would like a straight answer, like YES or NO. But straight answers are in short supply, particularly when we are talking about acupuncture.

Let me explain.

Acupuncture is part of ‘Traditional Chinese Medicine’ (TCM). It is said to re-balance the life forces that determine our health. As such it is seen as a panacea, a treatment for all ills. Therefore, the question, does it work?, ought to be more specific: does it work for pain, obesity, fatigue, hair-loss, addiction, anxiety, ADHA, depression, asthma, old age, etc.etc. As we are dealing with virtually thousands of ills, the question, does it work?, quickly explodes into thousands of more specific questions.

But that’s not all!

The question, does acupuncture work?, assumes that we are talking about one therapy. Yet, there are dozens of different acupuncture traditions and sites:

- body acupuncture,

- ear acupuncture,

- tongue acupuncture,

- scalp acupuncture,

- etc., etc.

Then there are dozens of different ways to stimulate acupuncture points:

- needle acupuncture,

- electroacupuncture,

- acupressure,

- moxibustion,

- ultrasound acupuncture,

- laser acupuncture,

- etc., etc.

And then there are, of course, different acupuncture ‘philosophies’ or cultures:

- TCM,

- ‘Western’ acupuncture,

- Korean acupuncture,

- Japanese acupuncture,

- etc., etc.

If we multiply these different options, we surely arrive at thousands of different variations of acupuncture being used for thousands of different conditions.

But this is still not all!

To answer the question, does it work?, we today have easily around 10 000 clinical trials. One might therefore think that, despite the mentioned complexity, we might find several conclusive answers for the more specific questions. But there are very significant obstacles that are in our way:

- most acupuncture trials are of lousy quality;

- most were conducted by lousy researchers who merely aim at showing that acupuncture works rather that testing whether it is effective;

- most originate from China and are published in Chinese which means that most of us cannot access them;

- they get nevertheless included in many of the systematic reviews that are currently being published without non-Chinese speakers ever being able to scrutinise them;

- TCM is a hugely important export article for China which means that political influence is abundant;

- several investigators have noted that virtually 100% of Chinese acupuncture trials report positive results regardless of the condition that is being targeted;

- it has been reported that about 80% of studies emerging from China are fabricated.

Now, I think you understand why I hesitate every time a journalist asks me:

DOES ACUPUNCTURE WORK?

Most journalists do not have the patience to listen to all the complexity this question evokes. Many do not have the intellectual capacity to comprehend an exhaustive reply. But all want to hear a simple and conclusive answer.

So, what do I say in this situation?

Usually, I respond that the answer would depend on who one asks. An acupuncturist is likely to say: YES, OF COURSE, IT DOES! An less biased expert might reply:

IT’S COMPLEX, BUT THE MOST RELIABLE EVIDENCE IS FAR FROM CONVINCING.

Dry needling is a therapy that is akin to acupuncture and trigger point therapy. It is claimed to be safe – but is this true?

Researchers from Ghent presented a series of 4 women aged 28 to 35 who were seen at the emergency department (ED) with post-dry needling pneumothorax between September 2022 and December 2023. None of the patients had any relevant medical history. All had been treated for a painful left shoulder, trapezius muscle or neck region in outpatient physiotherapist practices. At least three different physiotherapists were involved.

One patient presented to the ER on the same day as the dry needling procedure, the others presented the day after. All mentioned thoracic pain and dyspnoea. Clinical examination in all of these patients was unremarkable, as were their vital signs. Diagnosis was confirmed with ultrasound (US) and chest X-ray (CXR) in all patients. The latter exam showed left-sided apical pleural detachment with a median of 3.65 cm in expiration.

Two patients were managed conservatively. One patient (initial pneumothorax 2.5 cm) was discharged. The US two days later displayed a normally expanded lung. One patient with an initial apical size of 2.8 cm was admitted with 2 litres of oxygen through a nasal canula and discharged from the hospital the next day after US had shown no increase in size. Her control CXR 4 days later showed only minimal pleural detachment measuring 6 mm. The two other patients were treated with US guided needle aspiration. One patient with detachment initially being 4.5 cm showed decreased size of the pneumothorax immediately after aspiration. She was admitted to the respiratory medicine ward and discharged the next day. Control US and CXR after 1 week showed no more signs of pneumothorax. In the other patient, with detachment initially being 5.5 cm, needle aspiration resulted in complete deployment on US immediately after the procedure, but control CXR showed a totally collapsed lung 3 hours later. A small bore chest drain was placed but persistent air leakage was seen. Several trials of clamping the drain resulted in recurrent collapsing of the lung. After CT-scan had shown no structural deformities of the lung, suction was gradually reduced and the drain was successfully removed on the sixth day after placement. The patient was then discharged home. Control CXR 3 weeks later was normal.

The authors concluded that post-dry needling pneumothorax is, contrary to numbers cited in literature, not extremely rare. With rising popularity of the technique we expect complications to occur more often. Patients and referring doctors should be aware of this. In their informed consent practitioners should mention pneumothorax as a considerable risk of dry needling procedures in the neck, shoulder or chest region.

The crucial question, in my view, is this: do the risks of dry-needling out weigh the risks of this form of therapy? Let’s have a look at some of the recent evidence that we discussed on this blog:

- Spinal Manipulation and Electrical Dry Needling for Subacromial Pain Syndrome: A Nonsensical Trial

- Dry needling is useless for rehabilitation after shoulder surgery

- High velocity, low amplitude techniques are not superior to no treatment in the management of tension-type headache

- Which treatments are best for acute and subacute mechanical non-specific low back pain? A systematic review with network meta-analysis

- Acupuncture for chronic pain: the new NICE guideline

- Acupuncture for the Relief of Chronic Pain? A new, thorough synthesis fails to produce strong evidence that acupuncture works

The evidence is clearly mixed and unconvincing. I am not sure whether it is strong enough to afford a positive risk/benefit balance. In other words: dry needling is a therapy that might best be avoided.

After the nationwide huha created by the BBC’s promotion of auriculotherapy and AcuSeeds, it comes as a surprise to learn that, in Kent (UK), the NHS seems to advocate and provide this form of quackery. Here is the text of the patient leaflet:

Kent Community Health, NHS Foundation Trust

Auriculotherapy

This section provides information to patients who might benefit from auriculotherapy, to complement their acupuncture treatment, as part of their chronic pain management plan.

What is auriculotherapy?

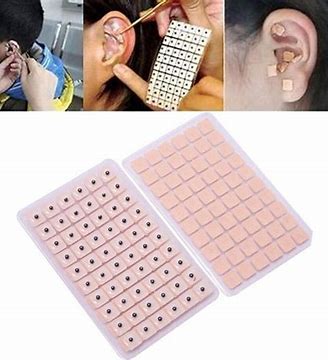

In traditional Chinese medicine, the ear is seen as a microsystem representing the entire body. Auricular acupuncture focuses on ear points that may help a wide variety of conditions including pain. Acupuncture points on the ear are stimulated with fine needles or with earseeds and massage (acupressure).

How does it work?

Recent research has shown that auriculotherapy stimulates the release of natural endorphins, the body’s own feel good chemicals, which may help some patients as part of their chronic pain management plan.

What are earseeds?

Earseeds are traditionally small seeds from the Vaccaria plant, but they can also be made from different types of metal or ceramic. Vaccaria earseeds are held in place over auricular points by a small piece of adhesive tape, or plaster. Applying these small and barely noticeable earseeds between acupuncture treatments allows for patient massage of the auricular points. Earseeds may be left in place for up to a week.

Who can use earseeds?

Earseeds are sometimes used by our Chronic Pain Service to prolong the effects of standard acupuncture treatments and may help some patients to self manage their chronic pain.

How can I get the most out my treatment with earseeds?

It is recommended that the earseeds are massaged two to three times a day or when symptoms occur by applying gentle pressure to the earseeds and massaging in small circles.

Will using earseeds cure my chronic pain?

As with any treatment, earseeds are not a cure but they can reduce pain levels for some patients as part of their chronic pain management programme.

________________________

What the authors of the leaflet forgot to tell the reader is this:

- Auriculotherapy is based on ideas that fly in the face of science.

- The evidence that auriculotherapy works is flimsy, to say the least.

- The evidence earseeds work is even worse.

- To arrive at a positive recommendation, the NHS had to heavily indulge in the pseudo-scientific art of cherry-picking.

- The positive experience that some patients report is due to a placebo response.

- For whichever condition auriculotherapy is used, there are treatments that are much more adequate.

- Advocating auriculotherapy is therefore not in the best interest of the patient.

- Arguably, it is unethical.

- Definitely, it is not what the NHS should be doing.

Dragons’ Den is a British reality television business programme, presented by Evan Davis and based upon the original Japanese series. The show allows several entrepreneurs an opportunity to present their varying business ideas to a panel of five wealthy investors, the “Dragons” of the show’s title, and pitch for financial investment while offering a stake of the company in return.

It has been reported that Giselle Boxer began selling needle-free acupuncture kits for ears after being diagnosed with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). She said the technique had helped improve her own health. Ms Boxer worked for advertising agency before starting her business. A researcher on the show had contacted her to ask if she would like to take part.

Entrepreneur and former footballer Gary Neville was so impressed with her pitch he made her an offer in full before the Dragons had a chance to begin asking questions. She said the impact on the business since the show aired had been “bonkers”. “It’s just been a complete whirlwind,” she said.

The tiny beads are a needle-free form of auriculotherapy, designed to stimulate specific points of the ear to address physical and emotional health concerns. “It completely transformed my life alongside lots and lots of other things like diet, lifestyle changes, meditation, breathwork and movement,” said Ms Boxer. She has since had a child and claimed she was fully healed within a year. “It was like a full overhaul of my life,” Ms Boxer said. Her business, Acu Seeds, sells kits for people to use at home and made a £64,000 profit in its first year, she added.

On the Acu Seed website, we learn the following:

Ear seeds are a form of auriculotherapy, which is the stimulation of specific points of the ear to support physical and emotional health concerns. They are a needle-free form of acupuncture that have been used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for thousands of years. TCM teaches that the ear is a microsystem of the whole body, where certain points on the ear correspond to different organs or body parts. Energy pathways (or ‘qi’ or vital life energy) pass through the ear and ear seeds stimulate specific points which send an abundant flow of energy to the related organ or area that needs attention. Think of it like reflexology, but for the ears instead of feet.

Ear seeds also create continual, gentle pressure on nerve impulses in the ear which send messages to the brain that certain organs or systems need support. The brain will then send signals and chemicals to the rest of the body to support whatever ailments you’re experiencing, releasing endorphins into the bloodstream, relaxing the nervous system, and naturally soothing pain and discomfort. Some people use ear seeds alongside acupuncture treatments as they may help the effects of acupuncture last longer between sessions.

I am impressed by the lingo used here:

- support physical and emotional health concerns – the seeds support the concerns but not the health?

- a needle-free form of acupuncture – sorry, the seeds don’t puncture anything; they exert pressure; therefore it’s called acuPRESSURE.

- have been used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for thousands of years – no, it was invented just a few decades ago by Paul Nogier.

- TCM teaches that the ear is a microsystem of the whole body – TCM teaches plenty of nonsense but not this one.

- Energy pathways (or ‘qi’ or vital life energy) pass through the ear –Qi is nothing more than a figment of the imagination of TCM advocates.

- send an abundant flow of energy to the related organ or area – only if you believe in your own fictional form of physiology.

- Think of it like reflexology – which btw is also nonsense.

- nerve impulses in the ear send messages to the brain that certain organs or systems need support – only if you believe in your own fictional form of physiology.

- The brain will then send signals and chemicals to the rest of the body – only if you believe in your own fictional form of physiology.

- help the effects of acupuncture last longer – help the non-existing effects of acupuncture last longer?

One the website, we also learn what for which conditions the treatment is effective:

Ear seeds may support a broad spectrum of health concerns including anxiety, stress, headaches, digestion, immunity, focus, sleep and fatigue. Our ear seed kits include the protocol ear maps for these eight health concerns and each protocol uses between 3 to 5 ear seeds. Ear seeds have also been found to support with women’s health issues like menstrual issues, libido, fertility, postpartum issues, inflammation, menopause and weight loss. The ear maps for these issues are given in our women’s health ear seed kit bundles. The specific combination of seed placements will support your chosen health concern. Further issues that they may support with are addiction, pain, tinnitus, vertigo, thyroid health and more.

Here, I am afraid, we might have a major problem:

THERE IS NO GOOD EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT ANY OF THESE CLAIMS!

I thus do wonder whether the venture of Giselle Boxer might be a case for the Advertising Standards Authority.

This study evaluated the effect of ear acupressure (auriculotherapy) on the weight-gaining pattern of overweight women during pregnancy. It was a single-blinded randomized clinical trial conducted between January and September 2022 and took place in health centers of Qom University of Medical Sciences in Iran.

One-hundred thirty overweight pregnant women were selected by a purposeful sampling method and then divided into two groups by block randomization method. In the intervention group, two seeds were placed in the left ear on the metabolism and stomach points, while two seeds were placed in the right ear on the mouth and appetite points. Participants in the intervention group were instructed to press the seeds six times a day, 20 minutes before a meal for five weeks. For the placebo group, the Vaccaria seedless label was placed at the same points as the intervention group.

A digital scale with an accuracy of 0.1 kg was used to weigh the pregnant women during each visit. Descriptive statistics, independent T-test, chi-square, and repeated measure ANOVA (analysis of variance) test were used to check the research objectives.

There was a statistically significant difference between the auriculotherapy and placebo groups immediately after completing the study (1120.68 ± 425.83 vs. 2704.09 ± 344.96 (g); = 0.018), respectively. Also, there was a substantial difference in the weight gain of women two weeks (793.10 ± 278.38 vs. 1090.32 ± 330.31 (g); < 0.001) and four weeks after the intervention (729.31 ± 241.52 vs. 964.51 ± 348.35 (g); < 0.001) between the auriculotherapy and placebo groups.

The authors concluded that the results of the present study indicated the effectiveness of auriculotherapy in controlling the weight gain of overweight pregnant women. This treatment could be used as a safe method, with easy access, and low cost in low-risk pregnancies.

In order to understand these findings, it is worth reading the methods section of the paper. It explains what actually happened with the two groups:

After providing explanations to familiarize the participants with the working method and answering their questions, the participants were requested to be comfortable. The first author who has an auriculotherapy certificate did the intervention. The intervention began by disinfecting both ears with a 70% alcohol solution. After determining the location of metabolism and stomach points in the left ear and mouth and appetite points in the right ear related to weight and appetite control, the researcher placed the seeds on the desired points… The intervention lasted for a total of 5 weeks. The seeds were changed twice a week (once every three days) by the researcher. The participants in the intervention group were taught to press the seeds 6 times a day for one minute each time. The pressure method was to use moderate stimulation with continuous pressure. In the first session, the researcher fully taught the participants the amount of pressure and the duration of it in a practical way and asked them to do this once in her presence to ensure that it was correct. Participants were recommended to do this preferably 20 minutes before eating. The researcher reminded the participants in the intervention group of their daily interventions by phone or text message. Each night, they were asked to check if they had followed the instructions and completed the daily registration checklist. In each seed replacement session, which was performed every three days, the checklist of the previous session was viewed and checked, and a checklist was received every week at the same time as the participants were weighed. Subjects were also emphasized in case of any symptoms of allergies or infections and pain as soon as possible through the contact number provided to them to discuss the issue with the researcher to remove the seeds.

In the placebo group, instead of real seeds, a label without Vaccaria seed (waterproof fabric adhesive) was placed by the researcher at the desired points in both ears, and the participants did not receive training to compress the points. They also did not receive the list of daily pressing points. All follow-ups and replacement of labels were performed in the same way as the intervention group in the placebo group. Finally, all participants were requested to notify the researcher if any seeds or labels were removed for any reason. It should be noted that pregnant mothers were unaware of the nature of the group to which they belonged.

It seems clear, therefore, that the patients were NOT blinded and that the verum patients received different care and more attention/encouragement than the placebo group. This means firstly that the trial was NOT single-blind, as the authors claim. Secondly, it means that the outcomes were most likely NOT due to ear acupressure at all – they were caused by the non-specific effects of expectation, extra attention, etc. which, in turn, motivated the women to better control their weight. Consequently, the conclusions of this study should be re-phrased:

The results of the present study fail to indicate the effectiveness of auriculotherapy in controlling the weight gain of overweight pregnant women.

In addition, I feel that the researchers, supervisors, peer-reviewers, editors should all bow their heads in shame for trying to mislead us.

My ‘ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME‘ (the group of people who have managed to publish nothing but positive findings about a dubious therapy) currently consists of 20 members (unless I have forgotten somone, which is possible, of course):

- Jorge Vas (acupuncture, Spain)

- Wane Jonas (homeopathy, US)

- Harald Walach (various SCAMs, Germany)

- Andreas Michalsen ( various SCAMs, Germany)

- Jennifer Jacobs (homeopath, US)

- Jenise Pellow (homeopath, South Africa)

- Adrian White (acupuncturist, UK)

- Michael Frass (homeopath, Austria)

- Jens Behnke (research officer, Germany)

- John Weeks (editor of JCAM, US)

- Deepak Chopra (entrepreneur, US)

- Cheryl Hawk (US chiropractor)

- David Peters (osteopathy, homeopathy, UK)

- Nicola Robinson (TCM, UK)

- Peter Fisher (homeopathy, UK)

- Simon Mills (herbal medicine, UK)

- Gustav Dobos (various SCAMs, Germany)

- Claudia Witt (homeopathy, Germany/Switzerland)

- George Lewith (acupuncture, UK)

- John Licciardone (osteopathy, US)

Today, it is time to add the 21st member. My last post was about a weird study co-authored by someone who struck me as truly remarkable. Terry Oleson is employed by the Department of Traditional Oriental Medicine, Emperor’s College of Traditional Oriental Medicine, Santa Monica, CA, USA. On ‘research gate‘, he describes his expertise as follows:

- Cognitive Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Biological Psychology

- Clinical Trials

- Addiction Medicine

- Allied Health Science

Oleson received his BA in Biology from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1967, his MA in Psychology from California State University at Long Beach in 1971, and his PhD from UC Irvine in 1973. He went on to conduct a postdoctoral scholarship at UCLA at that time, where he conducted pioneering research in auricular diagnosis and auriculotherapy. Since many years, Oleson has published on auricular acupuncture and acupressure, at least one book and the papers listed below. This is an oddly dubious and biologically implausible so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Terry Oleson – whom I never knowingly met in person – and his research are all the more remarkable: in his hands auricular therapy seems to work of just about everything:

- Effect of auricular acupressure on postpartum blues: A randomized sham controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2023 Aug;52:101762. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2023.101762. Epub 2023 Apr 10.PMID: 37060791

- Auriculotherapy stimulation for neuro-rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation. 2002;17(1):49-62.PMID: 12016347

- Acupuncture: the search for biologic evidence with functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography techniques. J Altern Complement Med. 2002 Aug;8(4):399-401. doi: 10.1089/107555302760253577.PMID: 12230898

- Commentary on auricular acupuncture for cocaine abuse. J Altern Complement Med. 2002 Apr;8(2):123-5. doi: 10.1089/107555302317371406.PMID: 12013511

- Clinical Commentary on an Auricular Marker Associated with COVID-19. Med Acupunct. 2020 Aug 1;32(4):176-177. doi: 10.1089/acu.2020.29152.com. Epub 2020 Aug 13.PMID: 32913483

- Comparison of Auricular Therapy with Sham in Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2020 Jun;26(6):515-520. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0477. Epub 2020 May 20.PMID: 32434376

- Application of Polyvagal Theory to Auricular Acupuncture.Oleson T.Med Acupunct. 2018 Jun 1;30(3):123-125. doi: 10.1089/acu.2018.29085.tol.PMID: 29937963

- The effect of ear acupressure (auriculotherapy) on sexual function of lactating women: protocol of a randomized sham controlled trial. Trials. 2020 Aug 20;21(1):729. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04663-x.PMID: 32819441

- Randomized controlled study of premenstrual symptoms treated with ear, hand, and foot reflexology. Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Dec;82(6):906-11.PMID: 8233263

-

Auricular electrical stimulation and dental pain threshold. Anesth Prog. 1993;40(1):14-9.PMID: 8185085

- Rapid narcotic detoxification in chronic pain patients treated with auricular electroacupuncture and naloxone. Int J Addict. 1985 Sep;20(9):1347-60. doi: 10.3109/10826088509047771.PMID: 2867052

- Investigation of the effects of naloxone upon acupuncture analgesia. Pain. 1984 Jun;19(2):201-4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90872-8.PMID: 6462730

- Electroacupuncture & auricular electrial stimulation. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 1983;2(4):22-6. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.1983.5005987.PMID: 19493718

- An experimental evaluation of auricular diagnosis: the somatotopic mapping or musculoskeletal pain at ear acupuncture points. Pain. 1980 Apr;8(2):217-229. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90009-7.PMID: 7402685

14 papers about a dodgy SCAM without the hint of a negative finding! I hope we can all agree that this achievement makes Terry a worthy member of my ‘HALL OF FAME’, a group of people who, like Terry, have been able to publish nothing but positive findings about the most dubious SCAMs.

Welcome Terry!

Women experience more problems in their sexual functioning after childbirth. Due to the high prevalence of sexual problems during the lactation period, the World Health Organization suggests that measures are needed to improve women’s sexual functioning during breastfeeding. This study investigated the effect of auricular acupressure on sexual functioning among lactating women.

A randomized, sham-controlled trial was conducted between October 2019 to March 2020 in urban comprehensive health centers of Qazvin, Iran. Seventy-six women who had been lactating between six months and one year postpartum were randomly assigned to auricular acupressure group (n=38) or sham control group (n=38) using a balanced block randomization method. The intervention group received ear acupressure in 10 sessions (at four-day intervals) and control group received the sham intervention at the same intervals. Sexual functioning was the primary outcome of the study (assessed using the Female Sexual Function Index) before and at three time points post-intervention (immediately after, one month after, and two months after). The secondary outcome was sexual quality of life assessed using Sexual Quality of Life-Female Version.

Auricular acupressure had a large effect on female sexual functioning at all three post-intervention time points:

- immediately after the intervention (adjusted mean difference [95% CI]: 8.37 [6.27; 10.46] with Cohen’s d [95% CI]: 1.81[1.28; 2.34]),

- one month after the intervention (adjusted mean difference [95% CI]: 8.44 [6.41; 10.48] with Cohen’s d [95% CI]: 2.01 [1.46; 2.56]),

- two months after the intervention (adjusted mean difference [95% CI]: 7.43 [5.12; 9.71] with Cohen’s d [95% CI]: 1.57 [1.06; 2.08]).

Acupressure significantly increased participants’ sexual quality of life on the Sexual Quality of Life-Female scale by 13.73 points in the intervention group compared to the control group (p<0.001). The effect size of intervention for female sexual quality was large (adjusted Cohen’s d [95% CI]: 1.09 [0.58; 1.59]). Weekly frequency of sexual intercourse in the intervention group significantly increased compared to sham control group (p<0.001). These changes were clinically significant for sexual functioning and sexual quality of life.

The authors concluded that auricular acupressure was effective in increasing quality of sexual life and sexual functioning among lactating women. Although further research is needed to confirm the efficacy of auricular acupressure, based on the present study’s findings, the use of auricular acupressure by women’s healthcare providers after childbirth is recommended.

One possible explanation for this result is that the study was de-blinded; the sham treatment might not have been distinguished from the verum, or the verbal and/or non-verbal communications between the therapist and the patients contributed to a de-blinding effect. As the sucess of blinding was not reported and probably not even tested, we cannot know. The authors explain that auricular acupressure might improve both endocrine function (increased sex hormones including androgens and estrogens) and its physiological consequences (e.g., vaginal dryness, and vaginal epithelial atrophy), as well as reducing fatigue and insomnia problems (which might increase sexual desire).

Personally, I find this VERY hard to believe. Auricular acupressure or auriculotherapy, as it is also called, was invented by Paul Nogier in the 1950s. Its assumptions are not in line with our knowledge of anatomy and physiology. The different maps used by proponents of auriculotherapy show embarrassing disagreements. The therapy is being promoted as a treatment for many conditions. However, the clinical evidence that it might be effective is weak, not least because many of the clinical trials are of low quality and thus unreliable. One of the first rigorous tests of auriculotherapy was published in 1984 by one of the most prominent researchers of pain, R. Melzack. Here is the abstract[2]:

Enthusiastic reports of the effectiveness of electrical stimulation of the outer ear for the relief of pain (“auriculotherapy”) have led to increasing use of the procedure. In the present study, auriculotherapy was evaluated in 36 patients suffering from chronic pain, using a controlled crossover design. The first experiment compared the effects of stimulation of designated auriculotherapy points, and of control points unrelated to the painful area. A second experiment compared stimulation of designated points with a no-stimulation placebo control. Pain-relief scores obtained with the McGill Pain Questionnaire failed to show any differences in either experiment. It is concluded that auriculotherapy is not an effective therapeutic procedure for chronic pain.

Today we have an abundance of clinical trials of this therapy. Their results are by no means uniform. It is therefore best not to rely on single studies but on systematic reviews that include the evidence from all reliable trials. Our review concluded that “because of the paucity and of the poor quality of the data, the evidence for the effectiveness of auricular therapy for the symptomatic treatment of insomnia is limited. Further, rigorously designed trials are warranted to confirm these results.”[3] Other, less rigorous reviews arrive at more positive conclusions; due to the often poor quality of the primary studies, they should, however, be interpreted with great caution.[4]

The most frequently reported adverse events of auriculotherapy include local skin irritation and discomfort, mild tenderness or pain, and dizziness. Most of these events were transient, mild, and tolerable, and no serious adverse events were identified.[5]

In view of all this, I think that we need much more and much better evidence for auricular acupressure to be recommended for ANY condition.

[1] Wirz-Ridolfi A. The History of Ear Acupuncture and Ear Cartography: Why Precise Mapping of Auricular Points Is Important. Med Acupunct. 2019 Jun 1;31(3):145-156. doi: 10.1089/acu.2019.1349.

[2] Melzack, R., & Katz, J. (1984). Auriculotherapy fails to relieve chronic pain. A controlled crossover study. JAMA, 251(8), 1041–1043.

[3] Lee MS, Shin BC, Suen LK, Park TY, Ernst E (2008) Auricular acupuncture for insomnia: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 62(11):1744–1752.

[4] Usichenko, T. I., Hua, K., Cummings, M., Nowak, A., Hahnenkamp, K., Brinkhaus, B., & Dietzel, J. (2022). Auricular stimulation for preoperative anxiety – A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Journal of clinical anesthesia, 76, 110581.

[5] Tan JY, Molassiotis A, Wang T, Suen LK (2014) Adverse events of auricular therapy: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014:506758

This study investigated the potential benefits of auricular point acupressure on cerebrovascular function and stroke prevention among adults with a high risk of stroke.

A randomized controlled study was performed with 105 adults at high risk for stroke between March and July 2021. Participants were randomly allocated to receive either

- auricular point acupressure with basic lifestyle interventions (n = 53) or

- basic lifestyle interventions alone (n = 52) for 2 weeks.

The primary outcome was the kinematic and dynamic indices of cerebrovascular function, as well as the CVHP score at week 2, measured by the Doppler ultrasonography and pressure transducer on carotids.

Of the 105 patients, 86 finished the study. At week 2, the auricular point acupressure therapy with lifestyle intervention group had higher kinematic indices, cerebrovascular hemodynamic parameters score, and lower dynamic indices than the lifestyle intervention group.

The authors concluded that ccerebrovascular function and cerebrovascular hemodynamic parameters score were greater improved among the participants undergoing auricular point acupressure combined with lifestyle interventions than lifestyle interventions alone. Hence, the auricular point acupressure can assist the stroke prevention.

Acupuncture is a doubtful therapy.

Acupressure is even more questionable.

Ear acupressure is outright implausible.

The authors discuss that the physiological mechanism underlying the effect of APA therapy on cerebrovascular hemodynamic function is not fully understood at present. There may be two possible explanations.

- First, a previous study has demonstrated that auricular acupuncture can directly increase mean blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery.

- Second, cerebrovascular hemodynamic function is indirectly influenced by the effect of APA therapy on blood pressure.

I think there is a much simpler explanation: the observed effects are directly or indirectly due to placebo. As regular listeners of this blog know only too well by now, the A+B versus B study design cannot account for placebo effects. Sadly, the authors of this study hardly discuss this explanation – that’s why they had to publish their findings in just about the worst SCAM journal of them all: EBCAM.

Acupuncture is questionable.

Acupressure is highly questionable.

Auricular acupressure is extremely questionable.

This study investigated the effect of auricular acupressure on the severity of postpartum blues. A randomized sham-controlled trial was conducted from February to November 2021, with 74 participants who were randomly allocated into two groups of either routine care + auricular acupressure (n = 37), or routine care + sham control (n = 37). Vacaria seeds with special non-latex adhesives were used to perform auricular acupressure on seven ear acupoints. There were two intervention sessions with an interval of five days. In the sham group, special non-latex adhesives without vacaria seeds were attached in the same acupoints as the intervention group. The severity of postpartum blues, fatigue, maternal-infant attachment, and postpartum depression was assessed.

Auricular acupressure was associated with a significant effect in the reduction of postpartum blues on the 10th and 15th days after childbirth (SMD = −2.77 and −2.15 respectively), postpartum depression on the 21st day after childbirth (SMD = −0.74), and maternal fatigue on 10th, 15th and 21st days after childbirth (SMD = −2.07, −1.30 and −1.32, respectively). Also, the maternal-infant attachment was increased significantly on the 21st day after childbirth (SMD = 1.95).

The authors concluded that auricular acupressure was effective in reducing postpartum blues and depression, reducing maternal fatigue, and increasing maternal-infant attachment in the short-term after childbirth.

Let me put my doubts about these conclusions in the form of a few questions:

- If you had sticky tape on your ear, would you sometimes touch it?

- If you touched it, would you feel whether a vacaria seed was contained in it or not?

- Would you, therefore, say that such a trial could be properly blinded (not to forget the therapists who were, of course, in the know)?

- If the trial was thus de-blinded, would you claim that patient expectation did not influence the outcomes?

If you answered all of these questions with NO, you are – like I – of the opinion that the results of this trial could have easily been brought about, not by the alleged effects of acupressure, but by placebo and other non-specific effects.

Given the high prevalence of burdensome symptoms in palliative care (PC) and the increasing use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) therapies, research is needed to determine how often and what types of SCAM therapies providers recommend to manage symptoms in PC.

This survey documented recommendation rates of SCAM for target symptoms and assessed if, SCAM use varies by provider characteristics. The investigators conducted US nationwide surveys of MDs, DOs, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners working in PC.

Participants (N = 404) were mostly female (71.3%), MDs/DOs (74.9%), and cared for adults (90.4%). Providers recommended SCAM an average of 6.8 times per month (95% CI: 6.0-7.6) and used an average of 5.1 (95% CI: 4.9-5.3) out of 10 listed SCAM modalities. Respondents recommended mostly:

- mind-body medicines (e.g., meditation, biofeedback),

- massage,

- acupuncture/acupressure.

The most targeted symptoms included:

- pain,

- anxiety,

- mood disturbances,

- distress.

Recommendation frequencies for specific modality-for-symptom combinations ranged from little use (e.g. aromatherapy for constipation) to occasional use (e.g. mind-body interventions for psychiatric symptoms). Finally, recommendation rates increased as a function of pediatric practice, noninpatient practice setting, provider age, and proportion of effort spent delivering palliative care.

The authors concluded that to the best of our knowledge, this is the first national survey to characterize PC providers’ SCAM recommendation behaviors and assess specific therapies and common target symptoms. Providers recommended a broad range of SCAM but do so less frequently than patients report using SCAM. These findings should be of interest to any provider caring for patients with serious illness.

Initially, one might feel encouraged by these data. Mind-body therapies are indeed supported by reasonably sound evidence for the symptoms listed. The evidence is, however, not convincing for many other forms of SCAM, in particular massage or acupuncture/acupressure. So encouragement is quickly followed by disappointment.

Some people might say that in PC one must not insist on good evidence: if the patient wants it, why not? But the point is that there are several forms of SCAMs that are backed by good evidence for use in PC. So, why not follow the evidence and use those? It seems to me that it is not in the patients’ best interest to disregard the evidence in medicine – and this, of course, includes PC.