Monthly Archives: April 2018

On this blog, we have seen more than enough evidence of how some proponents of alternative medicine can react when they feel cornered by critics. They often direct vitriol in their direction. Ad hominem attacks are far from being rarities. A more forceful option is to sue them for libel. In my own case, Prince Charles went one decisive step further and made sure that my entire department was closed down. In China, they have recently and dramatically gone even further.

This article in Nature tells the full story:

A Chinese doctor who was arrested after he criticized a best-selling traditional Chinese remedy has been released, after more than three months in detention. Tan Qindong had been held at the Liangcheng county detention centre since January, when police said a post Tan had made on social media damaged the reputation of the traditional medicine and the company that makes it.

On 17 April, a provincial court found the police evidence for the case insufficient. Tan, a former anaesthesiologist who has founded several biomedical companies, was released on bail on that day. Tan, who lives in Guangzhou in southern China, is now awaiting trial. Lawyers familiar with Chinese criminal law told Nature that police have a year to collect more evidence or the case will be dismissed. They say the trial is unlikely to go ahead…

The episode highlights the sensitivities over traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) in China. Although most of these therapies have not been tested for efficacy in randomized clinical trials — and serious side effects have been reported in some1 — TCM has support from the highest levels of government. Criticism of remedies is often blocked on the Internet in China. Some lawyers and physicians worry that Tan’s arrest will make people even more hesitant to criticize traditional therapies…

Tan’s post about a medicine called Hongmao liquor was published on the Chinese social-media app Meipian on 19 December…Three days later, the liquor’s maker, Hongmao Pharmaceuticals in Liangcheng county of Inner Mongolia autonomous region, told local police that Tan had defamed the company. Liangcheng police hired an accountant who estimated that the damage to the company’s reputation was 1.4 million Chinese yuan (US$220,000), according to official state media, the Beijing Youth Daily. In January, Liangcheng police travelled to Guangzhou to arrest Tan and escort him back to Liangcheng, according to a police statement.

Sales of Hongmao liquor reached 1.63 billion yuan in 2016, making it the second best-selling TCM in China that year. It was approved to be sold by licensed TCM shops and physicians in 1992 and approved for sale over the counter in 2003. Hongmao Pharmaceuticals says that the liquor can treat dozens of different disorders, including problems with the spleen, stomach and kidney, as well as backaches…

Hongmao Pharmaceuticals did not respond to Nature’s request for an interview. However, Wang Shengwang, general manager of the production center of Hongmao Liquor, and Han Jun, assistant to the general manager, gave an interview to The Paper on 16 April. The pair said the company did not need not publicize clinical trial data because Hongmao liquor is a “protected TCM composition”. Wang denied allegations in Chinese media that the company pressured the police to pursue Tan or that it dispatched staff to accompany the police…

Xia is worried that the case could further silence public criticism of TCMs, environmental degredation, and other fields where comment from experts is crucial. The Tan arrest “could cause fear among scientists” and dissuade them from posting scientific comments, he says.

END OF QUOTE

On this blog, we have repeatedly discussed concerns over the validity of TCM data/material that comes out of China (see for instance here, here and here). This chilling case, I am afraid, is not prone to increase our confidence.

My friend Gustav Born FRS died on 16 April 2018.

My friend Gustav Born FRS died on 16 April 2018.

Gustav was born into a Jewish family that emigrated from 1930s Goettingen (Germany) to the UK. His father Max, a friend of Einstein, was a physicist who received a Nobel Prize for his work in quantum mechanics. Gustav served in the British forces as a doctor during WW2. After the war, he became a pharmacologist in London and Cambridge who had many achievements to his name. For instance, he discovered the mechanisms through which the body stops bleeding and initiates blood clotting. He also invented the platelet aggregometer that is still used universally to quantify platelet activity and which he never patented so that not he but mankind would benefit from it. Gustav was indefatigable and continued his research for many years after his retirement. His work was crowned with uncounted scientific awards.

There have been numerous, much more detailed obituaries honouring Gustav e. g.:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/apr/26/gustav-born-obituary

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/gustav-born-obituary-gt5k9r8jc

Mine is merely a personal tribute. I met Gustav in the early 1990s while working in Vienna. We became close friends, and he took me under his wings, encouraged me to come to the UK, wrote a glowing reference when I applied for the Exeter post, and gave me moral support whenever I needed it.

After I had moved to the UK, we regularly met, and he even came to my 50th birthday party insisting to make a speech. About 15 years ago, he once attended one of my public lectures on alternative medicine; afterwards his comment was: “you know, your work is going to save lives.” Since my retirement, he kept phoning me at home (apparently Gustav had an irresistible attraction to the telephone) and urged me, usually speaking in German, to arrange a meeting. We always concluded that this must be soon; sadly, however, this did not happen.

Gustav was a great story-teller. One of his preferred anecdotes related to homeopathy. He recounted (interrupting himself giggling) that, when Einstein and his father once were talking, someone mentioned homeopathy and asked them what they thought of it. Einstein reflected for a little while and then said: “If one were to lock up 10 very clever people in a room and told them they were only allowed out once they had come up with the most stupid idea conceivable, they would soon come up with homeopathy.”

It is therefore not surprising that, when I invited Gustav to contribute a chapter to my book ‘HEALING, HYPE OR HARM?‘, he agreed to write an essay entitled ‘HOMEOPATHY IN CONTEXT’. Here is a short extract from it: What can be done to counteract the persistence of homeopathy? Its unwarranted claims must be continuously exposed. The diversion of public money from the proper purposed of the NHS must be stopped.

I shall miss Gustav for his clear thinking, his wry humour, his unfailing support and fatherly friendship.

The RCC is a relatively new organisation. It is a registered charity claiming to promote “professional excellence, quality and safety in chiropractic… The organisation promotes and supports high standards of education, practice and research, enabling chiropractors to provide, and to be recognised for providing, high quality care for patients.”

I have to admit that I was not impressed by the creation of the RCC and lately have not followed what they are up to – not a lot, I assumed. But now they seem to plan a flurry of most laudable activities:

The Royal College of Chiropractors is developing a range of initiatives designed to help chiropractors actively engage with health promotion, with a particular focus on key areas of public health including physical activity, obesity and mental wellbeing.

Dr Mark Gurden, Chair of the RCC Health Policy Unit, commented:

“Chiropractors are well placed to participate in public health initiatives. Collectively, they have several million opportunities every year in the UK to support people in making positive changes to their general health and wellbeing, as well as helping them manage their musculoskeletal health of course.

Our recent AGM & Winter Conference highlighted the RCC’s intentions to encourage chiropractors to engage with a public health agenda and we are now embarking on a programme to:

- Help chiropractors recognise the importance of their public health role;

- Help chiropractors enhance their knowledge and skills in providing advice and support to patients in key areas of public health through provision of information, guidance and training;

- Help chiropractors measure and recognise the impact they can have in key areas of public health.

To take this work forward, we will be exploring the possibility of launching an RCC Public Health Promotion & Wellbeing Society with a view to establishing a new Specialist Faculty in due course.”

END OF QUOTE

A ‘Public Health Promotion & Wellbeing Society’. Great!

As this must be new ground for the RCC, let me list a few suggestions as to how they could make more meaningful contributions to public health:

- They could tell their members that immunisations are interventions that save millions of lives and are therefore in the interest of public health. Many chiropractors still have a very disturbed attitude towards immunisation: anti-vaccination attitudes still abound within the chiropractic profession. Despite a growing body of evidence about the safety and efficacy of vaccination, many chiropractors do not believe in vaccination, will not recommend it to their patients, and place emphasis on risk rather than benefit. In case you wonder where this odd behaviour comes from, you best look into the history of chiropractic. D. D. Palmer, the magnetic healer who ‘invented’ chiropractic about 120 years ago, left no doubt about his profound disgust for immunisation: “It is the very height of absurdity to strive to ‘protect’ any person from smallpox and other malady by inoculating them with a filthy animal poison… No one will ever pollute the blood of any member of my family unless he cares to walk over my dead body… ” (D. D. Palmer, 1910)

- They could tell their members that chiropractic for children is little else than a dangerous nonsense for the sake of making money. Not only is there ‘not a jot of evidence‘ that it is effective for paediatric conditions, it can also cause serious harm. I fear that this suggestion is unlikely to be well-received by the RCC; they even have something called a ‘Paediatrics Faculty’!

- They could tell their members that making bogus claims is not just naughty but hinders public health. Whenever I look on the Internet, I find more false than true claims made by chiropractors, RCC members or not.

- They could tell their members that informed consent is not an option but an ethical imperative. Actually, the RCC do say something about the issue: The BMJ has highlighted a recent UK Supreme Court ruling that effectively means a doctor can no longer decide what a patient needs to know about the risks of treatment when seeking consent. Doctors will now have to take reasonable care to ensure the patient is aware of any material risks involved in any recommended treatment, and of any reasonable alternative or variant treatments. Furthermore, what counts as material risk can no longer be based on a responsible body of medical opinion, but rather on the view of ‘a reasonable person in the patient’s position’. The BMJ article is available here. The RCC feels it is important for chiropractors to be aware of this development which is relevant to all healthcare professionals. That’s splendid! So, chiropractors are finally being instructed to obtain informed consent from all their patients before starting treatment. This means that patients must be told that spinal manipulation is associated with very serious risks, AND that, in addition, ~ 50% of all patients will suffer from mild to moderate side effects, AND that there are always less risky and more effective treatments available for any condition from other healthcare providers.

- The RCC could, for the benefit of public health, establish a compulsory register of adverse effects after spinal manipulations and make the data from it available to the public. At present such a register does not exist, and therefore its introduction would be a significant step in the right direction.

- The RCC could make it mandatory for all members to adhere to the above points and establish a mechanism of monitoring their behaviour to make sure that, for the sake of public health, they all do take these issues seriously.

I do realise that the RCC may not currently have the expertise and know-how to adopt my suggestions, as these issues are rather new to them. To support the RCC in their praiseworthy endeavours, I herewith offer to give one or more evidence-based lectures on these subjects (at a date and place of their choice) in an attempt to familiarise the RCC and its members with these important aspects of public health. I also realise that the RCC may not have the funds to pay professorial lecture fees. Therefore, in the interest of both progress and public health, I offer to give these lectures for free.

I can be contacted via this blog.

Reflexology is an alternative therapy that is subjectively pleasant and objectively popular; it has been the subject on this blog before (see also here and here). Reflexologists assume that certain zones on the sole of our feet correspond to certain organs, and that their manual treatment can influence the function of these organs. Thus reflexology is advocated for all sorts of conditions, including infant colic.

The aim of this new study was to explore the effect of reflexology on infantile colic.

A total of 64 babies with colic were included in this study. Following a paediatrician’s diagnosis, two groups (study and control) were created. Socio-demographic data (including mother’s age, educational status, and smoking habits of parents) and medical history of the baby (including gender, birth weight, mode of delivery, time of the onset breastfeeding after birth, and nutrition style) were collected. The Infant Colic Scale (ICS) was used to estimate the colic severity in the infants. Reflexology was applied to the study group by the researcher and their mother 2 days a week for 3 weeks. The babies in the control group did not receive reflexology. Assessments were performed before and after the intervention in both groups.

The results show that the two groups were similar regarding socio-demographic background and medical history. While there was no difference between the groups in ICS scores before application of reflexology, the mean ICS score of the study group was significantly lower than that of control group at the end of the intervention.

The authors concluded that reflexology application for babies suffering from infantile colic may be a promising method to alleviate colic severity.

The authors seem to attribute the outcome to specific effects of reflexology.

However, they are mistaken!

Why?

Because their study does not control for the non-specific effects of the intervention.

Reflexology has not been shown to work for anything (“the best clinical evidence does not demonstrate convincingly reflexology to be an effective treatment for any medical condition“), and there is plenty of evidence to show that holding the baby, massaging it, cuddling it, rocking it or doing just about anything with it will have an effect, e. g.:

…kangaroo care for infants with colic is a promising intervention…

I think, in a way, this is rather good news; we do not need to believe in the hocus-pocus of reflexology in order to help our crying infants.

“In at least one article on chiropractic, Ernst has been shown to be fabricating data. I would not be surprised if he did the same thing with homeopathy. Ernst is a serial scientific liar.”

I saw this remarkable and charming Tweet yesterday. Its author is ‘Dr’ Avery Jenkins. Initially I was unaware of having had contact with him before; but when I checked my emails, I found this correspondence from August 2010:

Dr. Ernst:

Would you be so kind as to provide the full text of your article? Also, when would you be available for an interview for an upcoming feature article?

Thank you.

Avery L. Jenkins, D.C.

I put his title in inverted commas, because it turns out he is a chiropractor and not a medical doctor (but let’s not be petty!).

‘Dr’ Avery Jenkins runs a ‘Center for Alternative Medicine’ in the US: The Center has several features which set it apart from most other alternative medicine facilities, including the Center’s unique Dispensary. Stocked with over 300 herbs and supplements, the Dispensary’s wide range of natural remedies enables Dr. Jenkins to be the only doctor in Connecticut who provides custom herbal formulations for his patients. In our drug testing facility, we can provide on-site testing for drugs of abuse with immediate result reporting. Same-day appointments are available. Dr. Jenkins is also one of the few doctors in the state who has already undergone the federally-mandated training which will be necessary for all Department of Transportation Medical Examiners by 2014. Medical examinations for your Commercial Drivers License will take only 25 minutes, and Dr. Jenkins will provide you with all necessary paperwork.

The good ‘doctor’ also publishes a blog, and there I found a post from 2016 entirely dedicated to me. Here is an excerpt:

.. bias and hidden agendas come up in the research on alternative medicine and chiropractic in particular. Mostly this occurs in the form of journal articles using research that has been hand-crafted to make chiropractic spinal manipulation appear dangerous — when, in fact, you have a higher risk of serious injury while driving to your chiropractor’s office than you do of any treatment you receive while you’re there.

A case in point is the article, “Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review,” authored by Edzard Ernst, and published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 2007. Ernst concludes that, based on his review, “in the interest of patient safety we should reconsider our policy towards the routine use of spinal manipulation.”

This conclusion throws up several red flags, beginning with the fact that it flies in the face of most of the already-published, extensive research which shows that chiropractic care is one of the safest interventions, and in fact, is safer than medical alternatives.

For example, an examination of injuries resulting from neck adjustments over a 10-year period found that they rarely, if ever, cause strokes, and lumbar adjustments by chiropractors have been deemed by one of the largest studies ever performed to be safer and more effective than medical treatment.

So the sudden appearance of this study claiming that chiropractic care should be stopped altogether seems a bit odd.

As it turns out, the data is odd as well.

In 2012, a researcher at Macquarie University in Australia, set out to replicate Ernst’s study. What he found was shocking.

This subsequent study stated that “a review of the original case reports and case series papers described by Ernst found numerous errors or inconsistencies,” including changing the sex and age of patients, misrepresenting patients’ response to adverse events, and claiming that interventions were performed by chiropractors, when no chiropractor was even involved in the case.

“In 11 cases of the 21…that Ernst reported as [spinal manipulative therapy] administered by chiropractors, it is unlikely that the person was a qualified chiropractor,” the review found.

What is interesting here is that Edzard Ernst is no rookie in academic publishing. In fact, he is a retired professor and founder of two medical journals. What are the odds that a man with this level of experience could overlook so many errors in his own data?

The likelihood of Ernst accidentally allowing so many errors into his article is extremely small. It is far more likely that Ernst selected, prepared, and presented the data to make it fit a predetermined conclusion.

So, Ernst’s article is either extremely poor science, or witheringly inept fraud. I’ll let the reader draw their own conclusion.

Interestingly enough, being called out on his antics has not stopped Ernst from disseminating equally ridiculous research in an unprofessional manner. Just a few days ago, Ernst frantically called attention to another alleged chiropractic mishap, this one resulting in a massive brain injury.

Not only has he not learned his lesson yet, Ernst tried the same old sleight of hand again. The brain injury, as it turns out, didn’t happen until a week after the “chiropractic” adjustment, making it highly unlikely, if not impossible, for the adjustment to have caused the injury in the first place. Secondly, the adjustment wasn’t even performed by a chiropractor. As the original paper points out, “cervical manipulation is still widely practiced in massage parlors and barbers in the Middle East.” The original article makes no claim that the neck adjustment (which couldn’t have caused the problem in the first place) was actually performed by a chiropractor.

It is truly a shame that fiction published by people like Ernst has had the effect of preventing many people from getting the care they need. I can only hope that someday the biomedical research community can shed its childish biases so that we all might be better served by their findings.

END OF QUOTE

Here I will not deal with the criticism a Australian chiropractor published in a chiro-journal 5 years after my 2007 article (which incidentally was not primarily about chiropractic but about spinal manipulation). Suffice to say that my article did NOT contain ‘fabricated’ data. A full re-analysis would be far too tedious, for my taste (especially as criticism of it has been discussed in all of 7 ‘letters to the editor’ soon after its publication)

- Adverse effects of spinal manipulation. [J R Soc Med. 2007]

- Adverse effects of spinal manipulation. [J R Soc Med. 2007]

- Adverse effects of spinal manipulation. [J R Soc Med. 2007]

- Adverse effects of spinal manipulation. [J R Soc Med. 2007]

- Adverse effects of spinal manipulation. [J R Soc Med. 2007]

- Adverse effects of spinal manipulation. [J R Soc Med. 2007]

- Adverse effects of spinal manipulation. [J R Soc Med. 2007]

I will, however, address ‘Dr’ Avery Jenkins’ second allegation related to my recent (‘frantic’) blog-post. I will do this by simply copying the abstract of the paper in question:

Background: Multivessel cervical dissection with cortical sparing is exceptional in clinical practice. Case presentation: A 55-year-old man presented with acute-onset neck pain with associated sudden onset right-sided hemiparesis and dysphasia after chiropractic* manipulation for chronic neck pain. Results and Discussion: Magnetic resonance imaging revealed bilateral internal carotid artery dissection and left extracranial vertebral artery dissection with bilateral anterior cerebral artery territory infarctions and large cortical-sparing left middle cerebral artery infarction. This suggests the presence of functionally patent and interconnecting leptomeningeal anastomoses between cerebral arteries, which may provide sufficient blood flow to salvage penumbral regions when a supplying artery is occluded. Conclusion: Chiropractic* cervical manipulation can result in catastrophic vascular lesions preventable if these practices are limited to highly specialized personnel under very specific situations.

*my emphasis

With this, I rest my case.

The only question to be answered now is this: TO SUE OR NOT TO SUE?

What do you think?

Gosh, we in the UK needed that boost of jingoism (at least, if you are white, non-Jewish and equipped with a British passport)! But it’s all very well to rejoice at the news that we have a new little Windsor. With all the joy and celebration, we must not forget that the blue-blooded infant might be in considerable danger!

I am sure that chiropractors know what I am talking about.

KISS (Kinematic Imbalance due to Suboccipital Strain) is a term being used to describe a possible causal relation between imbalance in the upper neck joints in infants and symptoms like postural asymmetry, development of asymmetric motion patterns, hip problems, sleeping and eating disorders. Chiropractors are particularly fond of KISS. It is a problem that chiropractors tend to diagnose in new-borns.

This website explains further:

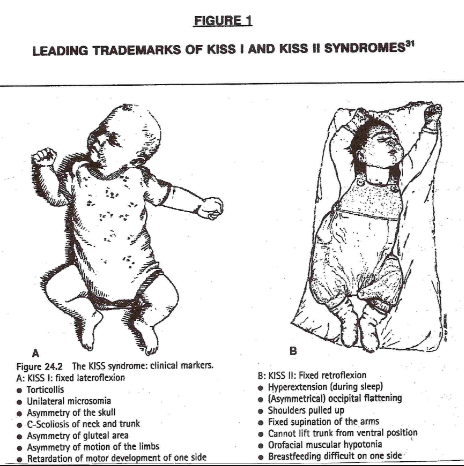

The kinematic imbalances brought on by the suboccipital strain at birth give rise to a concept in which symptoms and signs associated with the cervical spine manifest themselves into two easily recognizable clinical presentations. The leading characteristic is a fixed lateroflexion [called KISS I] or fixed retroflexion [KISS II]. KISS I may be associated with torticollis, asymmetry of the skull, C–scoliosis of the neck and trunk, asymmetry of the gluteal area and of the limbs, and retardation of the motor development of one side. KISS II, on the other hand, displays hyperextension during sleep, occipital flattening that may be asymmetrical, hunching of the shoulders, fixed supination of the arms, orofacial muscular hypotonia, failure to lift the trunk from a ventral position, and difficulty in breast feeding on one side. [34] The leading trademarks of both KISS I and KISS II are illustrated in Figure 1. [31]

In essence, these birth experiences lay the groundwork for rationalizing the wisdom of providing chiropractic healthcare to the pediatric population…

END OF QUOTE

KISS must, of course, be treated with chiropractic spinal manipulation: the manual adjustment is the most common, followed by an instrument adjustment. This removes the neurological stress, re-balances the muscles and normal head position. Usually a dramatic change can be seen directly after the appropriate adjustment has been given…

Don’t frown! We all know that we can trust our chiropractors.

Evidence?

Do you have to insist on being a spoil-sport?

Alright, alright, the evidence tells a different story. A systematic review concluded that, given the absence of evidence of beneficial effects of spinal manipulation in infants and in view of its potential risks, manual therapy, chiropractic and osteopathy should not be used in infants with the KISS-syndrome, except within the context of randomised double-blind controlled trials.

And this means I now must worry for a slightly different reason: we all know that the new baby was born into a very special family – a family that seems to embrace every quackery available! I can just see the baby’s grandfather recruiting a whole range of anti-vaccinationists, tree-huggers, spoon-benders, homeopaths, faith healers and chiropractors to look after the new-born.

By Jove, one does worry about one’s Royals!

Have you ever wondered whether doctors who practice homeopathy are different from those who don’t.

Silly question, of course they are! But how do they differ?

Having practised homeopathy myself during my very early days as a physician, I have often thought about this issue. My personal (and not very flattering) impressions were noted in my memoir where I describe my experience working in a German homeopathic hospital:

… some of my colleagues used homeopathy and other alternative approaches because they could not quite cope with the often exceedingly high demands of conventional medicine. It is almost understandable that, if a physician was having trouble comprehending the multifactorial causes and mechanisms of disease and illness, or for one reason or another could not master the equally complex process of reaching a diagnosis or finding an effective therapy, it might be tempting instead to employ notions such as dowsing, homeopathy or acupuncture, whose theoretical basis, unsullied by the inconvenient absolutes of science, was immeasurably more easy to grasp.

Some of my colleagues in the homeopathic hospital were clearly not cut out to be “real” doctors. Even a very junior doctor like me could not help noticing this somewhat embarrassing fact…

But this is anecdote and not evidence!

So, where is the evidence?

It was published last week and made headlines in many UK daily papers.

Our study was aimed at finding out whether English GP practices that prescribe any homeopathic preparations might differ in their prescribing of other drugs. We identified practices that made any homeopathy prescriptions over six months of data. We measured associations with four prescribing and two practice quality indicators using multivariable logistic regression.

Only 8.5% of practices (644) prescribed homeopathy between December 2016 and May 2017. Practices in the worst-scoring quartile for a composite measure of prescribing quality were 2.1 times more likely to prescribe homeopathy than those in the best category. Aggregate savings from the subset of these measures where a cost saving could be calculated were also strongly associated. Of practices spending the most on medicines identified as ‘low value’ by NHS England, 12.8% prescribed homeopathy, compared to 3.9% for lowest spenders. Of practices in the worst category for aggregated price-per-unit cost savings, 12.7% prescribed homeopathy, compared to 3.5% in the best category. Practice quality outcomes framework scores and patient recommendation rates were not associated with prescribing homeopathy.

We concluded that even infrequent homeopathy prescribing is strongly associated with poor performance on a range of prescribing quality measures, but not with overall patient recommendation or quality outcomes framework score. The association is unlikely to be a direct causal relationship, but may reflect underlying practice features, such as the extent of respect for evidence-based practice, or poorer stewardship of the prescribing budget.

Since our study was reported in almost all of the UK newspapers, it comes as no surprise that, in the interest of ‘journalistic balance’, homeopaths were invited to give their ‘expert’ opinions on our work.

Margaret Wyllie, head of the British Homeopathic Association, was quoted commenting: “This is another example of how real patient experience and health outcomes are so often discounted, when in actuality they should be the primary driver for research to improve our NHS services. This study provides no useful evidence about homeopathy, or about prescribing, and gives absolutely no data that can improve the health of people in the UK.”

The Faculty of Homeopathy was equally unhappy about our study and stated: “The study did not include any measures of patient outcomes, so it doesn’t tell us how the use of homeopathy in English general practice correlates with patients doing well or badly, nor with how many drugs they use.”

Cristal Summer from the Society of Homeopathy said that our research was just a rubbish bit of a study.

Peter Fisher, the Queen’s homeopath and the president of the Faculty of Homeopathy, stated: “We don’t know if these measures correlate with what matters to patients – whether they get better and have side-effects.”

A study aimed at determining whether GP practices that prescribe homeopathic preparations differ in their prescribing habits from those that do not prescribe homeopathics can hardly address these questions, Peter. A test of washing machines can hardly tell us much about the punctuality of trains. And an investigation into the risks of bungee jumping will not inform us about the benefits of regular exercise. Call me biased, but to me these comments indicate mainly one thing: HOMEOPATHS SEEM TO HAVE GREAT DIFFICULTIES UNDERSTANDING SCIENTIFIC PAPERS.

I much prefer the witty remarks of Catherine Bennett in yesterday’s Observer: Homeopath-GPs, naturally, have mustered in response and challenge Goldacre’s findings, with a concern for methodology that could easily give the impression that there is some evidential basis for their parallel system, beyond the fact that the Prince of Wales likes it. In fairness to Charles, his upbringing is to blame. But what is the doctors’ excuse?

Amongst all the implausible treatments to be found under the umbrella of ‘alternative medicine’, Reiki might be one of the worst, i. e. least plausible and outright bizarre (see for instance here, here and here). But this has never stopped enthusiasts from playing scientists and conducting some more pseudo-science.

This new study examined the immediate symptom relief from a single reiki or massage session in a hospitalized population at a rural academic medical centre. It was designed as a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on demographic, clinical, process, and quality of life for hospitalized patients receiving massage therapy or reiki. Hospitalized patients requesting or referred to the healing arts team received either a massage or reiki session and completed pre- and post-therapy symptom questionnaires. Differences between pre- and post-sessions in pain, nausea, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and overall well-being were recorded using an 11-point Likert scale.

Patients reported symptom relief with both reiki and massage therapy. Reiki improved fatigue and anxiety more than massage. Pain, nausea, depression, and well being changes were not different between reiki and massage encounters. Immediate symptom relief was similar for cancer and non-cancer patients for both reiki and massage therapy and did not vary based on age, gender, length of session, and baseline symptoms.

The authors concluded that reiki and massage clinically provide similar improvements in pain, nausea, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and overall well-being while reiki improved fatigue and anxiety more than massage therapy in a heterogeneous hospitalized patient population. Controlled trials should be considered to validate the data.

Don’t I just adore this little addendum to the conclusions, “controlled trials should be considered to validate the data” ?

The thing is, there is nothing to validate here!

The outcomes are not due to the specific effects of Reiki or massage; they are almost certainly caused by:

- the extra attention,

- the expectation of patients,

- the verbal or non-verbal suggestions of the therapists,

- the regression towards the mean,

- the natural history of the condition,

- the concomitant therapies administered in parallel,

- the placebo effect,

- social desirability.

Such pseudo-research only can only serve one purpose: to mislead (some of) us into thinking that treatments such as Reiki might work.

What journal would be so utterly devoid of critical analysis to publish such unethical nonsense?

Ahh … it’s our old friend the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine

Say no more!

Osteopathy is an odd alternative therapy. In many parts of the world it is popular; the profession differs dramatically from country to country; and there is not a single condition for which we could say that osteopathy out-performs other options. No wonder then that osteopaths would be more than happy to find a new area where they could practice their skills.

Perhaps surgical care is such an area?

The aim of this systematic review was to present an overview of published research articles within the subject field of osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) in surgical care. The authors evaluated peer-reviewed research articles published in osteopathic journals during the period 1990 to 2017. In total, 10 articles were identified.

Previous research has been conducted within the areas of abdominal, thoracic, gynecological, and/or orthopedic surgery. The studies included outcomes such as pain, analgesia consumption, length of hospital stay, and range of motion. Heterogeneity was identified in usage of osteopathic techniques, treatment duration, and occurrence, as well as in the osteopath’s experience.

The authors concluded that despite the small number of research articles within this field, both positive effects as well as the absence of such effects were identified. Overall, there was a heterogeneity concerning surgical contexts, diagnoses, signs and symptoms, as well as surgical phases in current interprofessional osteopathic publications. In this era of multimodal surgical care, the authors concluded, there is an urgent need to evaluate OMT in this context of care and with a proper research approach.

This is an odd conclusion, if there ever was one!

The facts are fairly straight forward:

- Osteopaths would like to expand into the area of surgical care [mainly, I suspect, because it would be good for business]

- There is no plausible reason why OMT should be beneficial in this setting.

- Osteopaths are not well-trained for looking after surgical patients.

- Physiotherapists, however, are and therefore there is no need for osteopaths on surgical wards.

- The evidence is extremely scarce.

- The available trials are of poor quality.

- Their results are contradictory.

- Therefore there is no reliable evidence to show that OMT is effective.

The correct conclusion of this review should thus be as follows:

THE AVAILABLE EVIDENCE FAILS TO SHOW EFFECTIVENESS OF OMT. THEREFORE THIS APPROACH CANNOT BE RECOMMENDED.

End of story.

I have often criticised papers published by chiropractors.

Not today!

This article is excellent and I therefore quote extensively from it.

The objective of this systematic review was to investigate, if there is any evidence that spinal manipulations/chiropractic care can be used in primary prevention (PP) and/or early secondary prevention in diseases other than musculoskeletal conditions. The authors conducted extensive literature searches to locate all studies in this area. Of the 13.099 titles scrutinized, 13 articles were included (8 clinical studies and 5 population studies). They dealt with various disorders of public health importance such as diastolic blood pressure, blood test immunological markers, and mortality. Only two clinical studies could be used for data synthesis. None showed any effect of spinal manipulation/chiropractic treatment.

The authors concluded that they found no evidence in the literature of an effect of chiropractic treatment in the scope of PP or early secondary prevention for disease in general. Chiropractors have to assume their role as evidence-based clinicians and the leaders of the profession must accept that it is harmful to the profession to imply a public health importance in relation to the prevention of such diseases through manipulative therapy/chiropractic treatment.

In addition to this courageous conclusion (the paper is authored by a chiropractor and published in a chiro journal), the authors make the following comments:

Beliefs that a spinal subluxation can cause a multitude of diseases and that its removal can prevent them is clearly at odds with present-day concepts, as the aetiology of most diseases today is considered to be multi-causal, rarely mono-causal. It therefore seems naïve when chiropractors attempt to control the combined effects of environmental, social, biological including genetic as well as noxious lifestyle factors through the simple treatment of the spine. In addition, there is presently no obvious emphasis on the spine and the peripheral nervous system as the governing organ in relation to most pathologies of the human body.

The ‘subluxation model’ can be summarized through several concepts, each with its obvious weakness. According to the first three, (i) disturbances in the spine (frequently called ‘subluxations’) exist and (ii) these can cause a multitude of diseases. (iii) These subluxations can be detected in a chiropractic examination, even before symptoms arise. However, to date, the subluxation has been elusive, as there is no proof for its existence. Statements that there is a causal link between subluxations and various diseases should therefore not be made. The fourth and fifth concepts deal with the treatment, namely (iv) that chiropractic adjustments can remove subluxations, (v) resulting in improved health status. However, even if there were an improvement of a condition following treatment, this does not mean that the underlying theory is correct. In other words, any improvement may or may not be caused by the treatment, and even if so, it does not automatically validate the underlying theory that subluxations cause disease…

Although at first look there appears to be a literature on this subject, it is apparent that most authors lack knowledge in research methodology. The two methodologically acceptable studies in our review were found in PubMed, whereas most of the others were identified in the non-indexed literature. We therefore conclude that it may not be worthwhile in the future to search extensively the non-indexed chiropractic literature for high quality research articles.

One misunderstanding requires some explanations; case reports are usually not considered suitable evidence for effect of treatment, even if the cases relate to patients who ‘recovered’ with treatment. The reasons for this are multiple, such as:

- Individual cases, usually picked out on the basis of their uniqueness, do not reflect general patterns.

- Individual successful cases, even if correctly interpreted must be validated in a ‘proper’ research design, which usually means that presumed effect must be tested in a properly powered and designed randomized controlled trial.

- One or two successful cases may reflect a true but very unusual recovery, and such cases are more likely to be written up and published as clinicians do not take the time to marvel over and spend time on writing and publishing all the other unsuccessful treatment attempts.

- Recovery may be co-incidental, caused by some other aspect in the patient’s life or it may simply reflect the natural course of the disease, such as natural remission or the regression towards the mean, which in human physiology means that low values tend to increase and high values decrease over time.

- Cases are usually captured at the end because the results indicate success, meaning that the clinical file has to be reconstructed, because tests were used for clinical reasons and not for research reasons (i.e. recorded by the treating clinician during an ordinary clinical session) and therefore usually not objective and reproducible.

- The presumed results of the treatment of the disease is communicated from the patient to the treating clinician and not to a third, neutral person and obviously this link is not blinded, so the clinician is both biased in favour of his own treatment and aware of which treatment was given, and so is the patient, which may result in overly positive reporting. The patient wants to please the sympathetic clinician and the clinician is proud of his own work and overestimates the results.

- The long-term effects are usually not known.

- Further, and most importantly, there is no control group, so it is impossible to compare the results to an untreated or otherwise treated person or group of persons.

Nevertheless, it is common to see case reports in some research journals and in communities with readers/practitioners without a firmly established research culture it is often considered a good thing to ‘start’ by publishing case reports.

Case reports are useful for other reasons, such as indicating the need for further clinical studies in a specific patient population, describing a clinical presentation or treatment approach, explaining particular procedures, discussing cases, and referring to the evidence behind a clinical process, but they should not be used to make people believe that there is an effect of treatment…

For groups of chiropractors, prevention of disease through chiropractic treatment makes perfect sense, yet the credible literature is void of evidence thereof. Still, the majority of chiropractors practising this way probably believe that there is plenty of evidence in the literature. Clearly, if the chiropractic profession wishes to maintain credibility, it is time seriously to face this issue. Presently, there seems to be no reason why political associations and educational institutions should recommend spinal care to prevent disease in general, unless relevant and acceptable research evidence can be produced to support such activities. In order to be allowed to continue this practice, proper and relevant research is therefore needed…

All chiropractors who want to update their knowledge or to have an evidence-based practice will search new information on the internet. If they are not trained to read the scientific literature, they might trust any article. In this situation, it is logical that the ‘believers’ will choose ‘attractive’ articles and trust the results, without checking the quality of the studies. It is therefore important to educate chiropractors to become relatively competent consumers of research, so they will not assume that every published article is a verity in itself…

END OF QUOTES

YES, YES YES!!!

I am so glad that some experts within the chiropractic community are now publishing statements like these.

This was long overdue.

How was it possible that so many chiropractors so far failed to become competent consumers of research?

Do they and their professional organisations not know that this is deeply unethical?

Actually, I fear they do and did so for a long time.

Why then did they not do anything about it ages ago?

I fear, the answer is as easy as it is disappointing:

If chiropractors systematically trained to become research-competent, the chiropractic profession would cease to exist; they would become a limited version of physiotherapists. There is simply not enough positive evidence to justify chiropractic. In other words, as chiropractic wants to survive, it has little choice other than remaining ignorant of the current best evidence.