osteopathy

Today, several UK dailies report about a review of osteopathy just published in BMJ-online. The aim of this paper was to summarise the available clinical evidence on the efficacy and safety of osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) for different conditions. The authors conducted an overview of systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses (MAs). SRs and MAs of randomised controlled trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of OMT for any condition were included.

The literature searches revealed nine SRs or MAs conducted between 2013 and 2020 with 55 primary trials involving 3740 participants. The SRs covered a wide range of conditions including

- acute and chronic non-specific low back pain (NSLBP, four SRs),

- chronic non-specific neck pain (CNSNP, one SR),

- chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP, one SR),

- paediatric (one SR),

- neurological (primary headache, one SR),

- irritable bowel syndrome (IBS, one SR).

Although with different effect sizes and quality of evidence, MAs reported that OMT is more effective than comparators in reducing pain and improving the functional status in acute/chronic NSLBP, CNSNP and CNCP. Due

to the small sample size, presence of conflicting results and high heterogeneity, questionable evidence existed on OMT efficacy for paediatric conditions, primary headaches and IBS. No adverse events were reported in most SRs. The methodological quality of the included SRs was rated low or critically low.

The authors concluded that based on the currently available SRs and MAs, promising evidence suggests the possible effectiveness of OMT for musculoskeletal disorders. Limited and inconclusive evidence occurs for paediatric conditions, primary headache and IBS. Further well-conducted SRs and MAs are needed to confirm and extend the efficacy and safety of OMT.

This paper raises several questions. Here a just the two that bothered me most:

- If the authors had truly wanted to evaluate the SAFETY of OMT (as they state in the abstract), they would have needed to look beyond SRs, MAs or RCTs. We know – and the authors of the overview confirm this – that clinical trials of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) often fail to mention adverse effects. This means that, in order to obtain a more realistic picture, we need to look at case reports, case series and other observational studies. It also means that the positive message about safety generated here is most likely misleading.

- The authors (the lead author is an osteopath) might have noticed that most – if not all – of the positive SRs were published by osteopaths. Their assessments might thus have been less than objective. The authors did not include one of our SRs (because it fell outside their inclusion period). Yet, I do believe that it is one of the few reviews of OMT for musculoskeletal problems that was not done by osteopaths. Therefore, it is worth showing you its abstract here:

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of osteopathy as a treatment option for musculoskeletal pain. Six databases were searched from their inception to August 2010. Only randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were considered if they tested osteopathic manipulation/mobilization against any control intervention or no therapy in human with any musculoskeletal pain in any anatomical location, and if they assessed pain as an outcome measure. The selection of studies, data extraction, and validation were performed independently by two reviewers. Studies of chiropractic manipulations were excluded. Sixteen RCTs met the inclusion criteria. Their methodological quality ranged between 1 and 4 on the Jadad scale (max = 5). Five RCTs suggested that osteopathy compared to various control interventions leads to a significantly stronger reduction of musculoskeletal pain. Eleven RCTs indicated that osteopathy compared to controls generates no change in musculoskeletal pain. Collectively, these data fail to produce compelling evidence for the effectiveness of osteopathy as a treatment of musculoskeletal pain.

It was published 11 years ago. But I have so far not seen compelling evidence that would make me change our conclusion. As I state in the newspapers:

OSTEOPATHY SHOULD BE TAKEN WITH A SIZABLE PINCH OF SALT.

Spinal cord injury after manual manipulation of the cervical spine is rare and has never been described as resulting from a patient performing a self-manual manipulation on his own cervical spine. This seems to be the first well-documented case of this association.

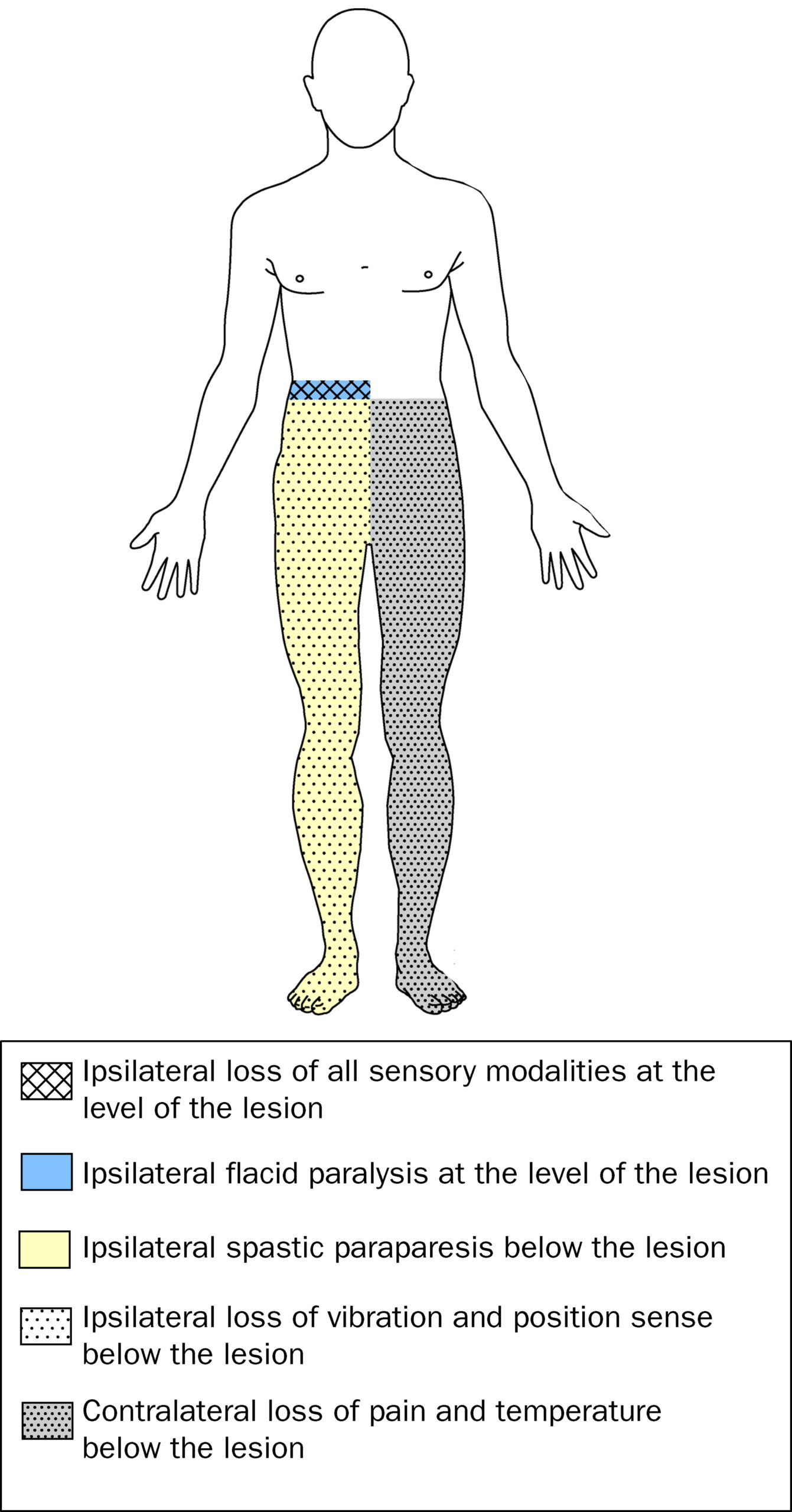

A healthy 29-year-old man developed Brown-Sequard syndrome immediately after performing a manipulation on his own cervical spine. Brown-Sequard syndrome is characterized by a lesion in the spinal cord which results in weakness or paralysis (hemiparaplegia) on one side of the body and a loss of sensation (hemianesthesia) on the opposite side.

Imaging showed large disc herniations at the levels of C4-C5 and C5-C6 with severe cord compression. The patient underwent emergent surgical decompression. He was discharged to an acute rehabilitation hospital, where he made a full functional recovery by postoperative day 8.

The authors concluded that this case highlights the benefit of swift surgical intervention followed by intensive inpatient rehab. It also serves as a warning for those who perform self-cervical manipulation.

I would add that the case also serves as a warning for those who are considering having cervical manipulation from a chiropractor. Such cases have been reported regularly. Here are three of them:

A spinal epidural hematoma is an extremely rare complication of cervical spine manipulation therapy (CSMT). The authors present the case of an adult woman, otherwise in good health, who developed Brown-Séquard syndrome after CSMT. Decompressive surgery performed within 8 hours after the onset of symptoms allowed for complete recovery of the patient’s preoperative neurological deficit. The unique feature of this case was the magnetic resonance image showing increased signal intensity in the paraspinal musculature consistent with a contusion, which probably formed after SMT. The pertinent literature is also reviewed.

Another case was reported of increased signal in the left hemicord at the C4 level on T2-weighted MR images after chiropractic manipulation, consistent with a contusion. The patient displayed clinical features of Brown-Séquard syndrome, which stabilized with immobilization and steroids. Follow-up imaging showed decreased cord swelling with persistent increased signal. After physical therapy, the patient regained strength on the left side, with residual decreased sensation of pain involving the right arm.

A further case was presented in which such a lesion developed after chiropractic manipulation of the neck. The patient presented with a Brown-Séquard syndrome, which has only rarely been reported in association with cervical epidural hematoma. The correct diagnosis was obtained by computed tomographic scanning. Surgical evacuation of the hematoma was followed by full recovery.

Brown-Séquard syndrome after spinal manipulation seems to be a rare event. Yet, nobody can provide reliable incidence figures because there is no post-marketing surveillance in this area.

This study explored the curative effects of remote home management combined with ‘Feng’s spinal manipulation’ on the treatment of elderly patients with lumbar disc herniation (LDH). (LDH is understood by the investigators to be a condition where lumbar disc degeneration or trauma causes the nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus to protrude towards the spinal canal and to constrict the spinal cord or nerve root.)

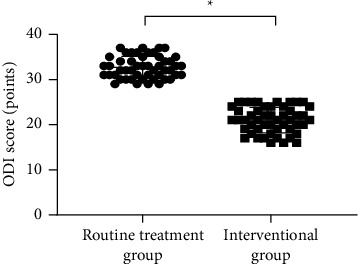

The clinical data of 100 patients with LDH were retrospectively reviewed. The 100 patients were equally divided into a routine treatment group and an interventional group according to the order of admission. The routine treatment group received conventional rehabilitation training, and the interventional group received remote home management combined with Feng’s spinal manipulation. The Oswestry disability index (ODI) and straight leg raising test were adopted for the assessment of the degrees of dysfunction and straight leg raising angles of the two groups after intervention. The curative effects of the two rehabilitation programs were evaluated.

Compared TO the routine treatment group, the interventional group had a remarkably higher excellent and good rate (P < 0.05), a significantly lower average ODI score after intervention (P < 0.001), notably higher straight leg raising angle, surface AEMG (average electromyogram) during stretching and tenderness threshold after intervention (P < 0.001), markedly lower muscular tension, surface AEMG during buckling, and flexion-extension relaxation ratio (FRR; (P < 0.001)), and much higher quality of life scores after intervention (P < 0.001).

The authors concluded that remote home management combined with Feng’s spinal manipulation, as a reliable method to improve the quality of life and the back muscular strength of the elderly patients with LDH, can substantially increase the straight leg raising angle and reduce the degree of dysfunction. Further study is conducive to establishing a better solution for the patients with LDH.

The authors state that “Feng’s spinal manipulation adopts spinal fixed-point rotation reduction to correct the vertebral displacement, and its curative effects have been confirmed in the treatment of sequestered LDH.” This is an odd statement: firstly, there is no vertebral displacement in LDH; secondly, if the treatment had been confirmed to be curative, why conduct this study?

Moreover, I don’t quite understand how the authors conducted a retrospective chart review and equally divide the 100 patients into two groups treated differently. What I do understand, however, is this:

- a retrospective review does not lend itself to conclusions about the effectiveness of any therapy;

- no type of spinal manipulation can hope to cure a lumbar disc degeneration or trauma that causes a herniation of the nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus.

Thus, I recommend we take this study with a sizable pinch of salt.

This paper is an evaluation of the relationship between chiropractic spinal manipulation and medical malpractice. The legal database VerdictSearch was queried using the terms “chiropractor” OR “spinal manipulation” under the classification of “Medical Malpractice” between 1988 and 2018. Cases with chiropractors as defendants were identified. Relevant medicolegal characteristics were obtained, including legal outcome (plaintiff/defense verdict, settlement), payment amount, nature of plaintiff claim, and type and location of the alleged injury.

Forty-eight cases involving chiropractic management in the US were reported. Of these, 93.8% (n = 45) featured allegations involving spinal manipulation. The defense (practitioner) was victorious in 70.8% (n = 34) of cases, with a plaintiff (patient) victory in 20.8% (n = 10) (mean payment $658,487 ± $697,045) and settlement in 8.3% (n = 4) (mean payment $596,667 ± $402,534).

Over-aggressive manipulation was the most frequent allegation (33.3%; 16 cases). A majority of cases alleged neurological injury of the spine as the reason for litigation (66.7%, 32 cases) with 87.5% (28/32) requiring surgery. C5-C6 disc herniation was the most frequently alleged injury (32.4%, 11/34, 83.3% requiring surgery) followed by C6-C7 herniation (26.5%, 9/34, 88.9% requiring surgery). Claims also alleged 7 cases of stroke (14.6%) and 2 rib fractures (4.2%) from manipulation therapy.

The authors concluded that litigation claims following chiropractic care predominately alleged neurological injury with consequent surgical management. Plaintiffs primarily alleged overaggressive treatment, though a majority of trials ended in defensive verdicts. Ongoing analysis of malpractice provides a unique lens through which to view this complicated topic.

The fact that the majority of trials ended in defensive verdicts does not surprise me. I once served as an expert witness in a trial against a UK chiropractor. Therefore, I know how difficult it is to demonstrate that the chiropractic intervention – and not anything else – caused the problem. Even cases that seem medically clear-cut, often allow reasonable doubt vis a vis the law.

Apologists will be quick and keen to point out that, in the US, there are many more successful cases brought against real doctors (healthcare professionals who have studied medicine). They are, of course, correct. But, at the same time, they miss the point. Real doctors treat real diseases where the outcomes are sadly often not as hoped. Litigation is then common, particularly in a litigious society like the US. Chiropractors predominantly treat symptoms like back troubles that are essentially benign. To create a fair comparison of litigations against doctors and chiros, one would therefore need to account for the type and severity of the conditions. Such a comparison has – to the best of my knowledge – not been done.

What has been done, however – and I did previously report about it – are comparisons between chiros, osteos, and physios (which seems to be a more level playing field). They show that complaints against chiros top the bill.

No 10-year follow-up study of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for lumbar intervertebral disc herniation (LDH) has so far been published. Therefore, the authors of this paper performed a prospective 10-year follow-up study on the integrated treatment of LDH in Korea.

One hundred and fifty patients from the baseline study, who initially met the LDH diagnostic criteria with a chief complaint of radiating pain and received integrated treatment, were recruited for this follow-up study. The 10-year follow-up was conducted from February 2018 to March 2018 on pain, disability, satisfaction, quality of life, and changes in a herniated disc, muscles, and fat through magnetic resonance imaging.

Sixty-five patients were included in this follow-up study. Visual analogue scale score for lower back pain and radiating leg pain were maintained at a significantly lower level than the baseline level. Significant improvements in Oswestry disability index and quality of life were consistently present. MRI confirmed that disc herniation size was reduced over the 10-year follow-up. In total, 95.38% of the patients were either “satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with the treatment outcomes and 89.23% of the patients claimed their condition “improved” or “highly improved” at the 10-year follow-up.

The authors concluded that the reduced pain and improved disability was maintained over 10 years in patients with LDH who were treated with nonsurgical Korean medical treatment 10 years ago. Nonsurgical traditional Korean medical treatment for LDH produced beneficial long-term effects, but future large-scale randomized controlled trials for LDH are needed.

This study and its conclusion beg several questions:

WHAT DID THE SCAM CONSIST OF?

The answer is not provided in the paper; instead, the authors refer to 3 previous articles where they claim to have published the treatment schedule:

The treatment package included herbal medicine, acupuncture, bee venom pharmacopuncture and Chuna therapy (Korean spinal manipulation). Treatment was conducted once a week for 24 weeks, except herbal medication which was taken twice daily for 24 weeks; (1) Acupuncture: frequently used acupoints (BL23, BL24, BL25, BL31, BL32, BL33, BL34, BL40, BL60, GB30, GV3 and GV4)10 ,11 and the site of pain were selected and the needles were left in situ for 20 min. Sterilised disposable needles (stainless steel, 0.30×40 mm, Dong Bang Acupuncture Co., Korea) were used; (2) Chuna therapy12 ,13: Chuna is a Korean spinal manipulation that includes high-velocity, low-amplitude thrusts to spinal joints slightly beyond the passive range of motion for spinal mobilisation, and manual force to joints within the passive range; (3) Bee venom pharmacopuncture14: 0.5–1 cc of diluted bee venom solution (saline: bee venom ratio, 1000:1) was injected into 4–5 acupoints around the lumbar spine area to a total amount of 1 cc using disposable injection needles (CPL, 1 cc, 26G×1.5 syringe, Shinchang medical Co., Korea); (4) Herbal medicine was taken twice a day in dry powder (2 g) and water extracted decoction form (120 mL) (Ostericum koreanum, Eucommia ulmoides, Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Achyranthes bidentata, Psoralea corylifolia, Peucedanum japonicum, Cibotium barometz, Lycium chinense, Boschniakia rossica, Cuscuta chinensis and Atractylodes japonica). These herbs were selected from herbs frequently prescribed for LBP (or nerve root pain) treatment in Korean medicine and traditional Chinese medicine,15 and the prescription was further developed through clinical practice at Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine.9 In addition, recent investigations report that compounds of C. barometz inhibit osteoclast formation in vitro16 and A. japonica extracts protect osteoblast cells from oxidative stress.17 E. ulmoides has been reported to have osteoclast inhibitive,18 osteoblast-like cell proliferative and bone mineral density enhancing effects.19 Patients were given instructions by their physician at treatment sessions to remain active and continue with daily activities while not aggravating pre-existing symptoms. Also, ample information about the favourable prognosis and encouragement for non-surgical treatment was given.

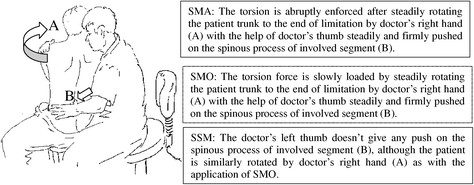

The traditional Korean spinal manipulations used (‘Chuna therapy’ – the references provided for it do NOT refer to this specific way of manipulation) seemed interesting, I thought. Here is an explanation from an unrelated paper:

Chuna, which is a traditional manual therapy practiced by Korean medicine doctors, has been applied to various diseases in Korea. Chuna manual therapy (CMT) is a technique that uses the hand, other parts of the doctor’s body or other supplementary devices such as a table to restore the normal function and structure of pathological somatic tissues by mobilization and manipulation. CMT includes various techniques such as thrust, mobilization, distraction of the spine and joints, and soft tissue release. These techniques were developed by combining aspects of Chinese Tuina, chiropratic, and osteopathic medicine.[13] It has been actively growing in Korea, academically and clinically, since the establishment of the Chuna Society (the Korean Society of Chuna Manual Medicine for Spine and Nerves, KSCMM) in 1991.[14] Recently, Chuna has had its effects nationally recognized and was included in the Korean national health insurance in March 2019.[15]

This almost answers the other questions I had. Almost, but not quite. Here are two more:

- The authors conclude that the SCAM produced beneficial long-term effects. But isn’t it much more likely that the outcomes their uncontrolled observations describe are purely or at least mostly a reflection of the natural history of lumbar disc herniation?

- If I remember correctly, I learned a long time ago in medical school that spinal manipulation is contraindicated in lumbar disc herniation. If that is so, the results might have been better, if the patients of this study had not received any SCAM at all. In other words, are the results perhaps due to firstly the natural history of the condition and secondly to the detrimental effects of the SCAM the investigators applied?

If I am correct, this would then be the 4th article reporting the findings of a SCAM intervention that aggravated lumbar disc herniation.

PS

I know that this is a mere hypothesis but it is at least as plausible as the conclusion drawn by the authors.

Low back pain (LBP) is influenced by interrelated biological, psychological, and social factors, however current back pain management is largely dominated by one-size fits all unimodal treatments. Team based models with multiple provider types from complementary professional disciplines is one way of integrating therapies to address patients’ needs more comprehensively.

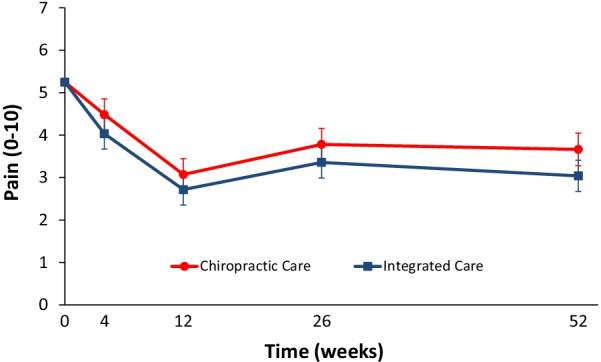

This parallel-group randomized clinical trial conducted from May 2007 to August 2010 aimed to evaluate the relative clinical effectiveness of 12 weeks of monodisciplinary chiropractic care (CC), versus multidisciplinary integrative care (IC), for adults with sub-acute and chronic LBP. The primary outcome was pain intensity and secondary outcomes were disability, improvement, medication use, quality of life, satisfaction, frequency of symptoms, missed work or reduced activities days, fear-avoidance beliefs, self-efficacy, pain coping strategies, and kinesiophobia measured at baseline and 4, 12, 26 and 52 weeks. Linear mixed models were used to analyze outcomes.

In total, 201 participants were enrolled. The largest reductions in pain intensity occurred at the end of treatment and were 43% for CC and 47% for IC. The primary analysis found IC to be significantly superior to CC over the 1-year period (P = 0.02). The long-term profile for pain intensity which included data from weeks 4 through 52, showed a significant advantage of 0.5 for IC over CC (95% CI 0.1 to 0.9; P = 0.02; 0 to 10 scale). The short-term profile (weeks 4 to 12) favored IC by 0.4, but was not statistically significant (95% CI – 0.02 to 0.9; P = 0.06). There was also a significant advantage over the long term for IC in some secondary measures (disability, improvement, satisfaction, and low back symptom frequency), but not for others (medication use, quality of life, leg symptom frequency, fear-avoidance beliefs, self-efficacy, active pain coping, and kinesiophobia). No serious adverse events resulted from either of the interventions.

The authors concluded that participants in the IC group tended to have better outcomes than the CC group, however, the magnitude of the group differences was relatively small. Given the resources required to successfully implement multidisciplinary integrative care teams, they may not be worthwhile, compared to monodisciplinary approaches like chiropractic care, for treating LBP.

The obvious question is: what were the exact treatments used in both groups? The authors provide the following explanations:

All participants in the study received 12 weeks of either monodisciplinary chiropractic care (CC) or multidisciplinary team-based integrative care (IC). CC was delivered by a team of chiropractors allowed to utilize any non-proprietary treatment under their scope of practice not shown to be ineffective or harmful including manual spinal manipulation (i.e., high velocity, low amplitude thrust techniques, with or without the assistance of a drop table) and mobilization (i.e., low velocity, low amplitude thrust techniques, with or without the assistance of a flexion-distraction table). Chiropractors also used hot and cold packs, soft tissue massage, teach and supervise exercise, and administer exercise and self-care education materials at their discretion. IC was delivered by a team of six different provider types: acupuncturists, chiropractors, psychologists, exercise therapists, massage therapists, and primary care physicians, with case managers coordinating care delivery. Interventions included acupuncture and Oriental medicine (AOM), spinal manipulation or mobilization (SMT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), exercise therapy (ET), massage therapy (MT), medication (Med), and self-care education (SCE), provided either alone or in combination and delivered by their respective profession. Participants were asked not to seek any additional treatment for their back pain during the intervention period. Standardized forms were used to document the details of treatment, as well as adverse events. It was not possible to blind patients or providers to treatment due to the nature of the study interventions. Patients in both groups received individualized care developed by clinical care teams unique to each intervention arm. Care team training was conducted to develop and support group dynamics and shared clinical decision making. A clinical care pathway, designed to standardize the process of developing recommendations, guided team-based practitioner in both intervention arms. Evidence based treatment plans were based on patient biopsychosocial profiles derived from the history and clinical examination, as well as baseline patient rated outcomes. The pathway has been fully described elsewhere [23]. Case managers facilitated patient care team meetings, held weekly for each intervention group, to discuss enrolled participants and achieve treatment plan recommendation consensus. Participants in both intervention groups were presented individualized treatment plan options generated by the patient care teams, from which they could choose based on their preferences.

This is undoubtedly an interesting study. It begs many questions. The two that puzzle me most are:

- Why publish the results only 12 years after the trial was concluded? The authors provide a weak explanation, but I would argue that it is unethical to sit on a publicly funded study for so long.

- Why did the researchers not include a third group of patients who were treated by their GP like in normal routine?

The 2nd question is, I think, important because the findings could mostly be a reflection of the natural history of LBP. We can probably all agree that, at present, the optimal treatment for LBP has not been found. To me, the results look as though they indicate that it hardly matters how we treat LBP, the outcome is always very similar. If we throw the maximum amount of care at it, the results tend to be marginally better. But, as the authors admit, there comes a point where we have to ask, is it worth the investment?

Perhaps the old wisdom is not entirely wrong (old because I learned it at medical school some 50 years ago): make sure LBP patients keep as active as they can while trying to ignore their pain as best as they can. It’s not a notion that would make many practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) happy – LBP is their No 1 cash cow! – but it would surely save huge amounts of public expenditure.

A multi-disciplinary research team assessed the effectiveness of interventions for acute and subacute non-specific low back pain (NS-LBP) based on pain and disability outcomes. For this purpose, they conducted a systematic review of the literature with network meta-analysis.

They included all 46 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) involving adults with NS-LBP who experienced pain for less than 6 weeks (acute) or between 6 and 12 weeks (subacute). Non-pharmacological treatments (eg, manual therapy) including acupuncture and dry needling or pharmacological treatments for improving pain and/or reducing disability considering any delivery parameters were included. The comparator had to be an inert treatment encompassing sham/placebo treatment or no treatment. The risk of bias was

- low in 9 trials (19.6%),

- unclear in 20 (43.5%),

- high in 17 (36.9%).

At immediate-term follow-up, for pain decrease, the most efficacious treatments against an inert therapy were:

- exercise (standardised mean difference (SMD) -1.40; 95% confidence interval (CI) -2.41 to -0.40),

- heat wrap (SMD -1.38; 95% CI -2.60 to -0.17),

- opioids (SMD -0.86; 95% CI -1.62 to -0.10),

- manual therapy (SMD -0.72; 95% CI -1.40 to -0.04).

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (SMD -0.53; 95% CI -0.97 to -0.09).

Similar findings were confirmed for disability reduction in non-pharmacological and pharmacological networks, including muscle relaxants (SMD -0.24; 95% CI -0.43 to -0.04). Mild or moderate adverse events were reported in the opioids (65.7%), NSAIDs (54.3%), and steroids (46.9%) trial arms.

The authors concluded that NS-LBP should be managed with non-pharmacological treatments which seem to mitigate pain and disability at immediate-term. Among pharmacological interventions, NSAIDs and muscle relaxants appear to offer the best harm-benefit balance.

The authors point out that previous published systematic reviews on spinal manipulation, exercise, and heat wrap did overlap with theirs: exercise (eg, motor control exercise, McKenzie exercise), heat wrap, and manual therapy (eg, spinal manipulation, mobilization, trigger points or any other technique) were found to reduce pain intensity and disability in adults with acute and subacute phases of NS-LBP.

I would add (as I have done so many times before) that the best approach must be the one that has the most favorable risk/benefit balance. Since spinal manipulation is burdened with considerable harm (as discussed so many times before), exercise and heat wraps seem to be preferable. Or, to put it bluntly:

if you suffer from NS-LBP, see a physio and not osteos or chiros!

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is among the most common types of pain in adults. It is also the domain for many types of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). However, their effectiveness remains questionable, and the optimal approach to CLBP remains elusive. Meditation-based therapies constitute a form of SCAM with high potential for widespread availability.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials evaluated the efficacy of meditation-based therapies for CLBP management. The primary outcomes were pain intensity, quality of life, and pain-related disability; the secondary outcomes were the experienced distress or anxiety and pain bothersomeness in the patients. The PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases were searched for studies published from their inception until July 2021, without language restrictions.

A total of 12 randomized clinical trials with 1153 patients were included. In 10 trials, meditation-based therapies significantly reduced the CLBP pain intensity compared with nonmeditation therapies (standardized mean difference [SMD] -0.27, 95% CI = -0.43 to – 0.12, P = 0.0006). In 7 trials, meditation-based therapies also significantly reduced CLBP bothersomeness compared with nonmeditation therapies (SMD -0.21, 95% CI = -0.34 to – 0.08, P = 0.002). In 3 trials, meditation-based therapies significantly improved patient quality of life compared with nonmeditation therapies (SMD 0.27, 95% CI = 0.17 to 0.37, P < 0.00001).

The authors concluded that meditation-based therapies constitute a safe and effective alternative approach for CLBP management.

The problem with this conclusion is that the primary studies are mostly of poor quality. For instance, they do not control for placebo effects (which is obviously not easy in this case). Thus, we need to take the conclusion with a pinch of salt.

However, since the same limitations apply to chiropractic and osteopathy, and since meditation has far fewer risks than these approaches, I would gladly recommend meditation over manipulative therapies. Or, to put it plainly: in terms of risk/benefit balance, meditation seems preferable to spinal manipulation.

On this blog, I have been regularly discussing the risks of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). In particular, I have often been writing about the risks of chiropractic spinal manipulations.

Why?

Some claim because I have an ax to grind – and, in a way, they are correct: I do feel strongly that consumers should be warned about the risks of all types of SCAM, and when it comes to direct risks, chiropractic happens to feature prominently.

But it’s all based on case reports which are never conclusive and usually not even well done.

This often-voiced chiropractic defense is, of course, is only partly true. But even if it were entirely correct, it would beg the question: WHY?

Why do we have to refer to case reports when discussing the risks of chiropractic? The answer is simple: Because there is no proper system of monitoring its risks.

And why not?

Chiropractors claim it is because the risks are non-existent or very rare or only minor or negligible compared to the risks of other therapies. This, I fear, is false. But how can I substantiate my fear? Perhaps by listing a few posts I have previously published on the direct risks of chiropractic spinal manipulation. Here is a list (probably not entirely complete):

- Chiropractic manipulations are a risk factor for vertebral artery dissections

- Vertebral artery dissection after chiropractic manipulation: yet another case

- The risks of (chiropractic) spinal manipulative therapy in children under 10 years

- A risk-benefit assessment of (chiropractic) neck manipulation

- The risk of (chiropractic) spinal manipulations: a new article

- New data on the risk of stroke due to chiropractic spinal manipulation

- The risks of manual therapies like chiropractic seem to out-weigh the benefits

- One chiropractic treatment followed by two strokes

- An outstanding article on the subject of harms of chiropractic

- Death by chiropractic neck manipulation? More details on the Lawler case

- Severe adverse effects of chiropractic in children Another serious complication after chiropractic manipulation; best to avoid neck manipulations altogether, I think

- Ophthalmic Adverse Effects after Chiropractic Neck Manipulation

- Is chiropractic treatment safe?

- Cervical artery dissection and stroke related to chiropractic manipulation

- We have an ethical, legal and moral duty to discourage chiropractic neck manipulations

- Cerebral Haemorrhage Following Chiropractic ‘Activator’ Treatment

- Vertebral artery dissection after chiropractic manipulation: yet another case

- Horner Syndrome after chiropractic spinal manipulation

- Phrenic nerve injury: a rare but serious complication of chiropractic neck manipulation

- Chiropractic neck manipulation can cause stroke

- Chiropractic and other manipulative therapies can also harm children

- Complications after chiropractic manipulations: probably rare but certainly serious

- Disc herniation after chiropractic

- Evidence for a causal link between chiropractic treatment and adverse effects

- More on the risks of spinal manipulation

- The risk of neck manipulation

- “As soon as the chiropractor manipulated my neck, everything went black”

- Spinal epidural haematoma after neck manipulation

- New review confirms: neck manipulations are dangerous

- Top model died ‘as a result of visiting a chiropractor’

- Another wheelchair filled with the help of a chiropractor

- Spinal manipulation: a treatment to die for?

Of course, one can argue about the conclusiveness of this or that case report, but I feel that the collective evidence discussed in these posts makes my point abundantly clear:

chiropractic spinal manipulation is not safe.

Vertebral artery dissection is an uncommon, but potentially fatal, vascular event. This case aimed to describe the pathogenesis and clinical presentation of vertebral artery dissection in a term pregnant patient. Moreover, the authors focused on the differential diagnosis, reviewing the available evidence.

A 39-year-old Caucasian woman presented at 38 + 4 weeks of gestation with a short-term history of vertigo, nausea, and vomiting. Symptoms appeared a few days after cervical spine manipulation by an osteopathic specialist. Urgent magnetic resonance imaging of the head was obtained and revealed an ischemic lesion of the right posterolateral portion of the brain bulb. A subsequent computed tomography angiographic scan of the head and neck showed a right vertebral artery dissection. Based on the correlation of the neurological manifestations and imaging findings, a diagnosis of vertebral artery dissection was established. The patient started low-dose acetylsalicylic acid and prophylactic enoxaparin following an urgent cesarean section.

Right vertebral artery dissection with ischemia in the posterolateral medulla oblongata. In DWI (a) and ADC map (b) the arrow shows a punctate, shiny ischemic lesion, with typical reduction of ADC in the right posterolateral medulla oblongata. c and d CT angiography (axial and 3D reformat, c and d, respectively) showing a focal dissection of the V2 distal segment of the right vertebral artery, with the arrow in figure c pointing to the dissection. e MRI angiography (time of flight, TOF) showing the absence of visualization of right PICA.

The authors concluded that vertebral artery dissection is a rare but potential cause of neurologic impairments in pregnancy and during the postpartum period. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis for women who present with headache and/or vertigo. Women with a history of migraines, hypertension, or autoimmune disorders in pregnancy are at higher risk, as well as following cervical spine manipulations. Prompt diagnosis and management of vertebral artery dissection are essential to ensure favorable outcomes.

In the discussion section, the authors point out that the incidence of VAD in pregnancy is twice as common as in the rest of the female population. They also mention that a review of the literature regarding adverse effects of spinal manipulation in the pregnant and postpartum periods identified adverse events in five pregnant women and two postpartum women. The authors also include a table that summarizes all cases of VAD reported both prior and after delivery, with 24 cases distributed with a prevalence during the postpartum period (19 of the 24 cases). The clinical presentation of these cases is varied, with a higher frequency of headaches, vertigo, and diplopia, and the risk factors most represented are hypertension and migraines.

The authors finish with this advice: practitioners who do spinal manipulations should be aware of the possible complications of neck manipulation in pregnancy and the postpartum period, particularly in mothers with underlying medical disorders that may predispose to vessel fragility and VAD.

I would add advice of a different nature: consumers should always question whether the risks of any intervention outweigh its benefit. In the case of neck manipulations, the answer is not positive.