physiotherapists

The aim of this evaluator-blinded randomized clinical trial was to determine if manual therapy added to a therapeutic exercise program produced greater improvements than a sham manual therapy added to the same exercise program in patients with non-specific shoulder pain.

Forty-five subjects were randomly allocated into one of three groups:

- manual therapy (glenohumeral mobilization technique and rib-cage technique);

- thoracic sham manual therapy (glenohumeral mobilization technique and rib-cage sham technique);

- sham manual therapy (sham glenohumeral mobilization technique and rib-cage sham technique).

All groups also received a therapeutic exercise program. Pain intensity, disability, and pain-free active shoulder range of motion were measured post-treatment and at 4-week and 12-week follow-ups. Mixed-model analyses of variance and post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were constructed for the analysis of the outcome measures.

All groups reported improved pain intensity, disability, and pain-free active shoulder range of motion. However, there were no between-group differences in these outcome measures.

The authors concluded that the addition of the manual therapy techniques applied in the present study to a therapeutic exercise protocol did not seem to add benefits to the management of subjects with non-specific shoulder pain.

What does that mean?

I think it means that the improvements observed in this study were due to 1) exercise and 2) a range of non-specific effects, and that they were not due to the manual techniques tested.

I cannot say that I find this enormously surprising. But I would also find it unsurprising if fans of these methods would claim that the results show that the physios applied the techniques not correctly.

In any case, I feel this is an interesting study, not least because of its use of sham therapy. But I somehow doubt that the patients were unable to distinguish sham from verum. If so, the study was not patient-blind which obviously is difficult to achieve with manual treatments.

This systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression investigated the effects of individualized interventions, based on exercise alone or combined with psychological treatment, on pain intensity and disability in patients with chronic non-specific low-back pain.

Databases were searched up to January 31, 2022, to retrieve respective randomized clinical trials of individualized and/or personalized and/or stratified exercise interventions with or without psychological treatment compared to any control.

The findings show:

- Fifty-eight studies (n = 10084) were included. At short-term follow-up (12 weeks), low-certainty evidence for pain intensity (SMD -0.28 [95%CI -0.42 to -0.14]) and very low-certainty evidence for disability (-0.17 [-0.31 to -0.02]) indicates superior effects of individualized versus active exercises, and very low-certainty evidence for pain intensity (-0.40; [-0.58 to -0.22])), but not (low-certainty evidence) for disability (-0.18; [-0.22 to 0.01]) compared to passive controls.

- At long-term follow-up (1 year), moderate-certainty evidence for pain intensity (-0.14 [-0.22 to -0.07]) and disability (-0.20 [-0.30 to -0.10]) indicates effects versus passive controls.

Sensitivity analyses indicate that the effects on pain, but not on disability (always short-term and versus active treatments) were robust. Pain reduction caused by individualized exercise treatments in combination with psychological interventions (in particular behavioral-cognitive therapies) (-0.28 [-0.42 to -0.14], low certainty) is of clinical importance.

The certainty of the evidence was downgraded mainly due to evidence of risk of bias, publication bias, and inconsistency that could not be explained. Individualized exercise can treat pain and disability in chronic non-specific low-back pain. The effects in the short term are of clinical importance (relative differences versus active 38% and versus passive interventions 77%), especially in regard to the little extra effort to individualize exercise. Sub-group analysis suggests a combination of individualized exercise (especially motor-control-based treatments) with behavioral therapy interventions to boost effects.

The authors concluded that the relative benefit of individualized exercise therapy on chronic low back pain compared to other active treatments is approximately 38% which is of clinical importance. Still, sustainability of effects (> 12 months) is doubtable. As individualization in exercise therapies is easy to implement, its use should be considered.

Johannes Fleckenstein, the 1st author from the Goethe-University Frankfurt, Institute of Sports Sciences, Department of Sports Medicine and Exercise Physiology, sees in the study “an urgent health policy appeal” to strengthen combined services in care and remuneration. “Compared to other countries, such as the USA, we are in a relatively good position in Germany. For example, we have a lower prescription of strong narcotics such as opiates. But the rate of unnecessary X-ray examinations, which incidentally can also contribute to the chronicity of pain, or inaccurate surgical indications is still very high.”

Personally, I find the findings of this paper rather unsurprising. As a clinician, many years ago, prescribing exercise therapy for low back pain was my daily bread. None of my team would have ever conceived the idea that exercise does not need to be individualized according to the needs and capabilities of each patient. Therefore, I suggest rephrasing the last sentence of the conclusion: As individualization in exercise therapies is easy to implement, its use should be standard procedure.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of craniosacral therapy on different features in migraine patients.

Fifty individuals with migraine were randomly divided into two groups (n = 25 per group):

- craniosacral therapy group (CTG),

- sham control group (SCG).

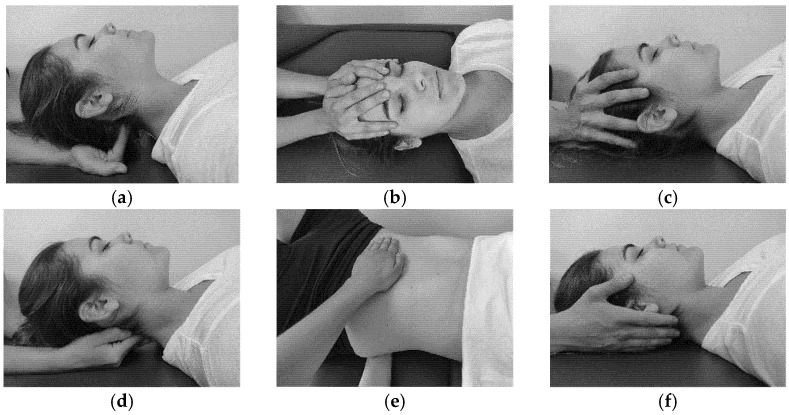

The interventions were carried out with the patient in the supine position. The CTG received a manual therapy treatment focused on the craniosacral region including five techniques, and the SCG received a hands-on placebo intervention. After the intervention, individuals remained supine with a neutral neck and head position for 10 min, to relax and diminish tension after treatment. The techniques were executed by the same experienced physiotherapist in both groups.

The analyzed variables were pain, migraine severity, and frequency of episodes, functional, emotional, and overall disability, medication intake, and self-reported perceived changes, at baseline, after a 4-week intervention, and at an 8-week follow-up.

After the intervention, the CTG significantly reduced pain (p = 0.01), frequency of episodes (p = 0.001), functional (p = 0.001) and overall disability (p = 0.02), and medication intake (p = 0.01), as well as led to a significantly higher self-reported perception of change (p = 0.01), when compared to SCG. The results were maintained at follow-up evaluation in all variables.

The authors concluded that a protocol based on craniosacral therapy is effective in improving pain, frequency of episodes, functional and overall disability, and medication intake in migraineurs. This protocol may be considered as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients.

Sorry, but I disagree!

And I have several reasons for it:

- The study was far too small for such strong conclusions.

- For considering any treatment as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients, we would need at least one independent replication.

- There is no plausible rationale for craniosacral therapy to work for migraine.

- The blinding of patients was not checked, and it is likely that some patients knew what group they belonged to.

- There could have been a considerable influence of the non-blinded therapists on the outcomes.

- There was a near-total absence of a placebo response in the control group.

Altogether, the findings seem far too good to be true.

Aging often contributes to a decrease in physical activity. As age advances, a decrease in muscle mass, muscle strength, and flexibility can impair physical function. One obvious way to prevent these developments might be regular physical exercise.

This open-label, randomized trial was intended to evaluate the effects of an integrated yoga module in improving the flexibility, muscle strength, and quality of life (QOL) of older adults. Participants were 96 older adults, aged 60-75 years (64.1 ± 3.95 years). The program was a three-month, yoga-based lifestyle intervention. The participants were randomly allocated to the intervention group (n = 48) or to a waitlisted control group (n = 48). The intervention group underwent three one-hour sessions of yoga weekly, with each session including loosening exercises, asanas, pranayama, and meditation spanning.

At baseline and post-intervention, the following assessments were made:

- spinal flexibility using a sit-and-reach test,

- back and leg strength using a back leg dynamometer,

- handgrip strength (HGS) and endurance (HGE) using a hand-grip dynamometer,

- Older People’s Quality of Life (OPQOL) questionnaire.

Analysis was performed employing Wilcoxon’s Sign Rank tests and Mann-Whitney Tests, using an intention-to-treat approach.

The results show that, compared to the control group, the intervention group experienced a significantly greater increase in spinal flexibility (P < .001), back leg strength (P < .001), HGE (P < .01), and QOL (P < .001) after three months of yoga.

The authors concluded that yoga can be used safely for older adults to improve flexibility, strength, and functional QOL. Larger randomized controlled trials with an active control intervention are warranted.

I agree with the authors that this trial was too small and not properly controlled. I disagree that their study shows yoga to be effective or safe. In fact, the two sentences of the conclusion do not seem to fit together at all.

Is it surprising that doing yoga exercises is better than doing nothing at all?

No!

Is it relevant to demonstrate this fact in an RCT?

No!

If anyone wants to test the value of yoga exercises, they must compare them to conventional exercises. And why don’t they do this? Could it be because they know they would be unlikely to show that yoga is superior?

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are highly prevalent, burdensome, and putatively associated with an altered human resting muscle tone (HRMT). Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is commonly and effectively applied to treat MSDs and reputedly influences the HRMT. Arguably, OMT may modulate alterations in HRMT underlying MSDs. However, there is sparse evidence even for the effect of OMT on HRMT in healthy subjects.

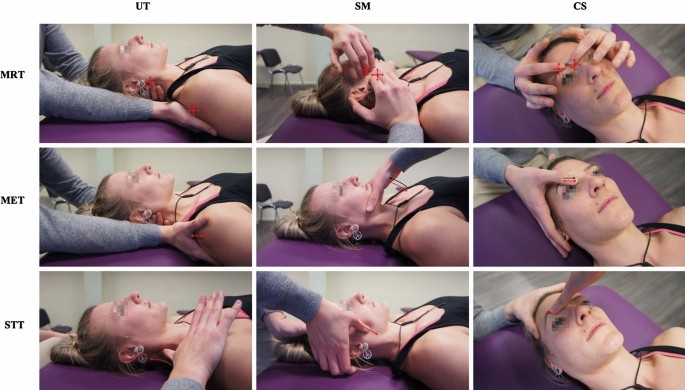

A 3 × 3 factorial randomized trial was performed to investigate the effect of myofascial release (MRT), muscle energy (MET), and soft tissue techniques (STT) on the HRMT of the corrugator supercilii (CS), superficial masseter (SM), and upper trapezius muscles (UT) in healthy subjects in Hamburg, Germany. Participants were randomised into three groups (1:1:1 allocation ratio) receiving treatment, according to different muscle-technique pairings, over the course of three sessions with one-week washout periods. We assessed the effect of osteopathic techniques on muscle tone (F), biomechanical (S, D), and viscoelastic properties (R, C) from baseline to follow-up (primary objective) and tested if specific muscle-technique pairs modulate the effect pre- to post-intervention (secondary objective) using the MyotonPRO (at rest). Ancillary, we investigate if these putative effects may differ between the sexes. Data were analysed using descriptive (mean, standard deviation, and quantiles) and inductive statistics (Bayesian ANOVA). 59 healthy participants were randomised into three groups and two subjects dropped out from one group (n = 20; n = 20; n = 19–2). The CS produced frequent measurement errors and was excluded from analysis. OMT significantly changed F (−0.163 [0.060]; p = 0.008), S (−3.060 [1.563]; p = 0.048), R (0.594 [0.141]; p < 0.001), and C (0.038 [0.017]; p = 0.028) but not D (0.011 [0.017]; p = 0.527). The effect was not significantly modulated by muscle-technique pairings (p > 0.05). Subgroup analysis revealed a significant sex-specific difference for F from baseline to follow-up. No adverse events were reported.

The authors concluded that OMT modified the HRMT in healthy subjects which may inform future research on MSDs. In detail, MRT, MET, and STT reduced the muscle tone (F), decreased biomechanical (S not D), and increased viscoelastic properties (R and C) of the SM and UT (CS was not measurable). However, the effect on HRMT was not modulated by muscle–technique interaction and showed sex-specific differences only for F.

I think that this study merits a few comments:

- It seems unsurprising that manual manipulation can relax muscles.

- The blinding of the volunteers was compromised because the participants were osteopathy students able to distinguish between the different interventions.

- The mechanisms underlying these reported changes in HRMT following OMT are unclear.

- The effects do not seem to be treatment-specific.

- The treatments used are not typical for osteopathy.

- Manual techniques are loosely defined or standardized.

- The duration of the effect is unknown but probably short.

- The size of the effect is small.

- The clinical relevance of the effect is doubtful.

Many systematic reviews have summarized the evidence on spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for low back pain (LBP) in adults. Much less is known about the older population regarding the effects of SMT. This paper assessed the effects of SMT on pain and function in older adults with chronic LBP in an individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis.

Electronic databases were searched from 2000 until June 2020; reference lists of eligible trials and related reviews were also searched. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were considered if they examined the effects of SMT in adults with chronic LBP compared to interventions recommended in international LBP guidelines. The authors of trials eligible for the IPD meta-analysis were contacted and invited to share data. Two review authors conducted a risk of bias assessment. Primary results were examined in a one-stage mixed model, and a two-stage analysis was conducted in order to confirm the findings. The main outcomes and measures were pain and functional status examined at 4, 13, 26, and 52 weeks.

A total of 10 studies were retrieved, including 786 individuals; 261 were between 65 and 91 years of age. There was moderate-quality evidence that SMT results in similar outcomes at 4 weeks (pain: mean difference [MD] – 2.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] – 5.78 to 0.66; functional status: standardized mean difference [SMD] – 0.18, 95% CI – 0.41 to 0.05). Second-stage and sensitivity analysis confirmed these findings.

The authors concluded that SMT provides similar outcomes to recommended interventions for pain and functional status in the older adult with chronic LBP. SMT should be considered a treatment for this patient population.

This is a fine analysis. Unfortunately, its results are less than fine. Its results confirm what I have been saying ad nauseam: we do not currently have a truly effective therapy for back pain, and most options are as good or as bad as the rest. This is most frustrating for everyone concerned, but it is certainly no reason to promote SMT as usually done by chiropractors or osteopaths.

The only logical solution, in my view, is to use those options that:

- are associated with the least risks,

- are the least expensive,

- are widely available.

However you twist and turn the existing evidence, the application of these criteria does not come up with chiropractic or osteopathy as an optimal solution. The best treatment is therapeutic exercise initially taught by a physiotherapist and subsequently performed as a long-term self-treatment by the patient at home.

When I first saw this, I was expecting something like If Homeopathy Beats Science (Mitchell and Webb) – YouTube : videos (reddit.com). But no, “Acute Care Homeopathy for Medical Professionals” is not a masterpiece by gifted satirists. It is much better; it is for real! In fact, it is a collaboration between the “Academy of Homeopathy Education” (AHE) and the American Institute of Homeopathy (AIH). Together, they published the following announcement:

Education” (AHE) and the American Institute of Homeopathy (AIH). Together, they published the following announcement:

AHE and AIH are pleased to present a customized educational program designed for busy medical professionals interested in enhancing their practice and expanding the treatment tools available with Homeopathy. Grounded in the original theory and philosophy of Homeopathy, AHE’s quality curriculum empowers practitioners and the material’s inspirational delivery encourages further study towards the mastery of Homeopathy for chronic care.

This course is open to all licensed healthcare providers— medical, osteopathic, naturopathic, dentists, chiropractors, veterinarians, nurse practitioners, nurses, physician assistants, pharmacologists and pharmacists.

Acute-care homeopathy addresses the challenges of 21st-century medical practice.

Among many things, you’ll learn safe and effective ways to manage pain and mitigate antibiotic overuse with FDA-regulated and approved Homeopathic remedies. AHE delivers an integrated learning experience that combines online real-time classroom experiences culminating in a telehealth based clinical internship allowing participants to study from anywhere in the world.

AHE’s team of Homeopathy experts have taught thousands of students around the globe and are known for unparalleled academic rigor, comprehensive clinical training, and robust research initiatives. AHE ensures that every graduate develops the necessary critical thinking skills in homeopathy case taking, analysis, and prescribing to succeed in practice with confidence and competence.

- Smart and savvy tech support team helps to on-board and train even the most reticent digital participants

- Academic support professionals provide an educational safety-net

- Stellar faculty to inspire confidence and encourage students to achieve their best work

- “Fireside Chats,” forums, and social gatherings build community

- Tried and true administrative systems keep things running smoothly so you can focus on learning Homeopathy.

All AHE students receive Radar Opus, the leading software package used by professional homeopaths worldwide.

Upon completion of the didactic program, practitioners begin an Acute Care Internship through AHE and the Homeopathy Help Network’s Acute Care Telehealth Clinic “Homeopathy Help Now” (HHN) which sees thousands of cases each year. Upon successful completion of the internship, practitioners will be invited to participate in ongoing supervised practice through HHN.

AHE is part of a larger vision to shape the future of Homeopathy: HOHM Foundation and the Homeopathy Help NetworkAll clinical services are delivered in an education and research-driven model. HOHM’s Office of Research has multiple peer-reviewed publications focused on education, practice, and clinical outcomes. HOHM is committed to funding Homeopathy study and research at every level.

The Academy of Homeopathy Education (AHE) operates in conjunction with HOHM Foundation, a 501c3 initiative committed to education, advocacy, and access. The Homeopathy Help Network is a telehealth clinic providing fee-for-service chronic care as well as donation-based acute care through Homeopathy Help Now.

____________________________

I suspect you simply cannot wait to enroll. To learn more about “Acute Care Homeopathy for Medical Professionals” please fill out the form.

… and don’t forget to pay the fee of US$ 5 500.

No, it’s not expensive, if you think about it. After all, acute-care homeopathy addresses the challenges of 21st-century medical practice.

Naprapathy is an odd variation of chiropractic. To be precise, it has been defined as a system of specific examination, diagnostics, manual treatment, and rehabilitation of pain and dysfunction in the neuromusculoskeletal system. It is aimed at restoring the function of the connective tissue, muscle- and neural tissues within or surrounding the spine and other joints. The evidence that it works is wafer-thin. Therefore rigorous studies are of interest.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of manual therapy compared with advice to stay active for working-age persons with nonspecific back and/or neck pain.

The two interventions were:

- a maximum of 6 manual therapy sessions within 6 weeks, including spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage, and stretching, performed by a naprapath (index group),

- information from a physician on the importance to stay active and on how to cope with pain, according to evidence-based advice, on 2 occasions within 3 weeks (control group).

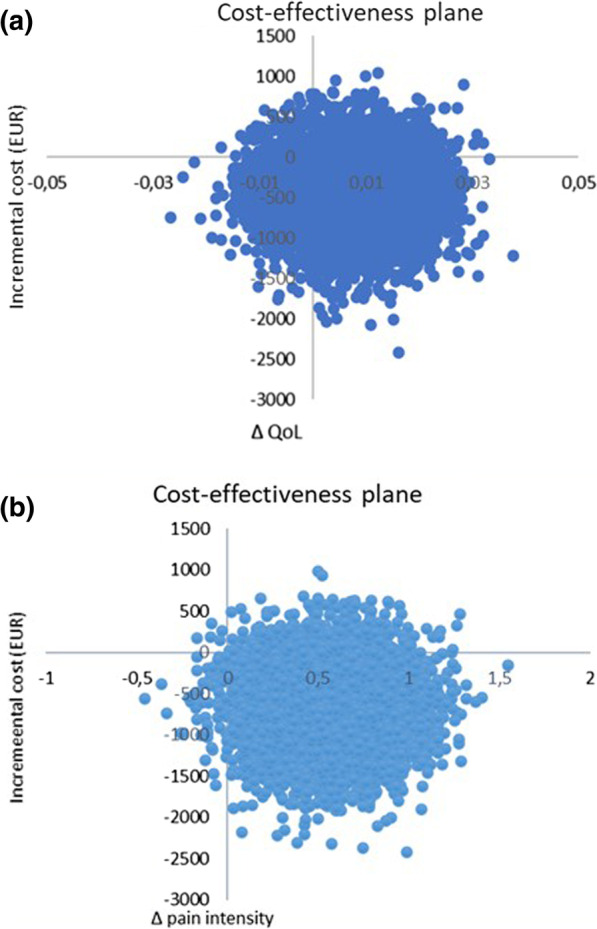

A cost-effectiveness analysis with a societal perspective was performed alongside a randomized controlled trial including 409 persons followed for one year, in 2005. The outcomes were health-related Quality of Life (QoL) encoded from the SF-36 and pain intensity. Direct and indirect costs were calculated based on intervention and medication costs and sickness absence data. An incremental cost per health-related QoL was calculated, and sensitivity analyses were performed.

The difference in QoL gains was 0.007 (95% CI – 0.010 to 0.023) and the mean improvement in pain intensity was 0.6 (95% CI 0.068-1.065) in favor of manual therapy after one year. Concerning the QoL outcome, the differences in mean cost per person were estimated at – 437 EUR (95% CI – 1302 to 371) and for the pain outcome the difference was – 635 EUR (95% CI – 1587 to 246) in favor of manual therapy. The results indicate that manual therapy achieves better outcomes at lower costs compared with advice to stay active. The sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main results.

Cost-effectiveness plane using bootstrapped incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for QoL and pain intensity outcomes

The authors concluded that these results indicate that manual therapy for nonspecific back and/or neck pain is slightly less costly and more beneficial than advice to stay active for this sample of working age persons. Since manual therapy treatment is at least as cost-effective as evidence-based advice from a physician, it may be recommended for neck and low back pain. Further health economic studies that may confirm those findings are warranted.

This is an interesting and well-conducted study. The differences between the groups seem small and of doubtful relevance. The authors acknowledge this fact by stating: “together with the clinical results from previously published studies on the same population the results suggest that manual therapy may be as cost-effective a treatment as evidence-based advice from a physician, for back and neck pain”. Moreover, the data do not convince me that the treatment per se was effective; it might have been the non-specific effects of touch and attention.

I have said it before: there is currently no optimal treatment for neck and back pain. Therefore, the findings even of rigorous cost-effectiveness studies will only generate lukewarm results.

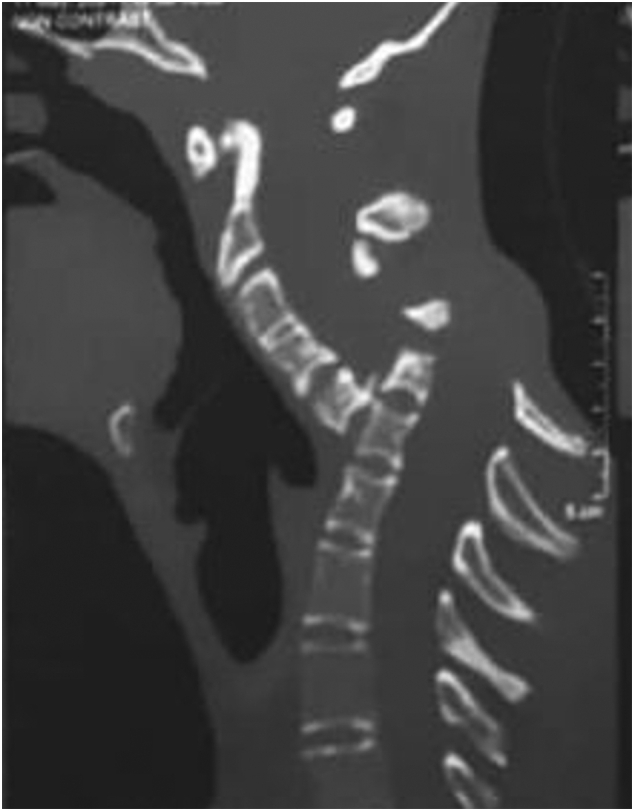

Spondyloptosis is a grade V spondylolisthesis – a vertebra having slipped so far with respect to the vertebra below that the two endplates are no longer congruent. It is usually seen in the lower lumbar spine but rarely can be seen in other spinal regions as well. Spondyloptosis is most commonly caused by trauma. It is defined as the dislocation of the spinal column in which the spondyloptotic vertebral body is either anteriorly or posteriorly displaced (>100%) on the adjacent vertebral body. Only a few cases of cervical spondyloptosis have been reported. The cervical cord injury in most patients is complete and irreversible. In most cases of cervical spondyloptosis, regardless of whether there is a neurologic deficit or not, reduction and stabilization of the fracture-dislocation is the management of choice

The case of a 16-year-old boy was reported who had been diagnosed with spondyloptosis of the cervical spine at the C5-6 level with a neurologic deficit following cervical manipulation by a traditional massage therapist. He could not move his upper and lower extremities, but the sensory and autonomic function was spared. The pre-operative American Spinal Cord Injury Association (ASIA) Score was B with SF-36 at 25%, and Karnofsky’s score was 40%. The patient was disabled and required special care and assistance.

The surgeons performed anterior decompression, cervical corpectomy at the level of C6 and lower part of C5, deformity correction, cage insertion, bone grafting, and stabilization with an anterior cervical plate. The patient’s objective functional score had increased after six months of follow-up and assessed objectively with the ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) E or (excellent), an SF-36 score of 94%, and a Karnofsky score of 90%. The patient could carry on his regular activity with only minor signs or symptoms of the condition.

The authors concluded that this case report highlights severe complications following cervical manipulation, a summary of the clinical presentation, surgical treatment choices, and a review of the relevant literature. In addition, the sequential improvement of the patient’s functional outcome after surgical correction will be discussed.

This is a dramatic and interesting case. Looking at the above pre-operative CT scan, I am not sure how the patient could have survived. I am also not aware of previous similar cases. This does, however, not mean they don’t exist. Perhaps most affected patients simply died without being diagnosed. So, do we need to add spondyloptosis to the (hopefully) rare but severe complications of spinal manipulation?

I know, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is not really a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) but it is used by many SCAM practitioners and pain patients. It is, therefore, worth knowing whether it works.

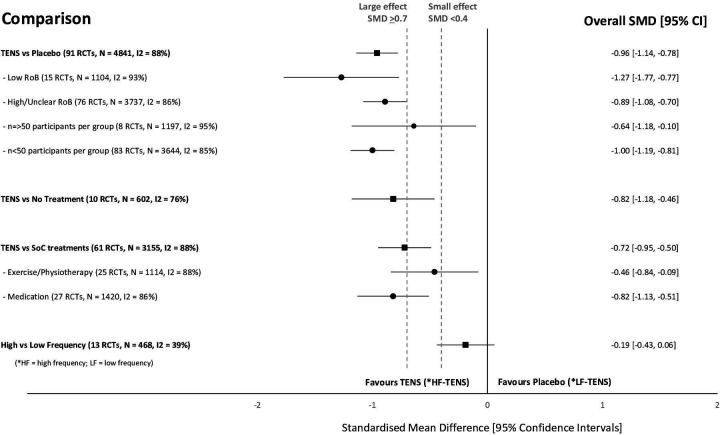

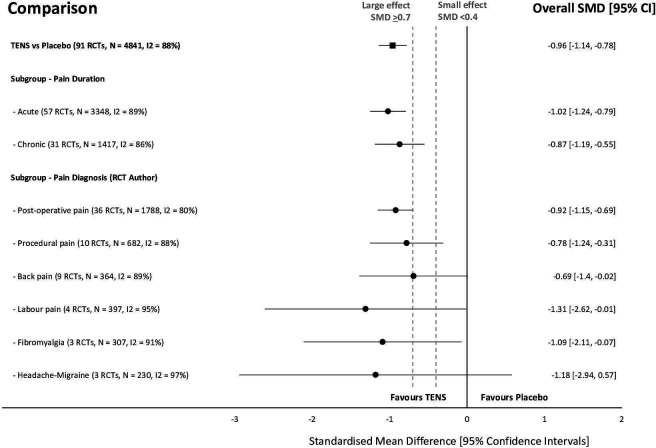

This systematic review investigated the efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for the relief of pain in adults. All randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were considered which compared strong non-painful TENS at or close to the site of pain versus placebo or other treatments in adults with pain, irrespective of diagnosis.

Reviewers independently screened, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias (RoB, Cochrane tool) and certainty of evidence (Grading and Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation). The outcome measures were the mean pain intensity and the proportions of participants achieving reductions of pain intensity (≥30% or >50%) during or immediately after TENS. Random effect models were used to calculate standardized mean differences (SMD) and risk ratios. Subgroup analyses were related to trial methodology and characteristics of pain.

The review included 381 RCTs (24 532 participants). Pain intensity was lower during or immediately after TENS compared with placebo (91 RCTs, 92 samples, n=4841, SMD=-0·96 (95% CI -1·14 to -0·78), moderate-certainty evidence). Methodological (eg, RoB, sample size) and pain characteristics (eg, acute vs chronic, diagnosis) did not modify the effect. Pain intensity was lower during or immediately after TENS compared with pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments used as part of standard of care (61 RCTs, 61 samples, n=3155, SMD = -0·72 (95% CI -0·95 to -0·50], low-certainty evidence). Levels of evidence were downgraded because of small-sized trials contributing to imprecision in magnitude estimates. Data were limited for other outcomes including adverse events which were poorly reported, generally mild, and not different from comparators.

The authors concluded that there was moderate-certainty evidence that pain intensity is lower during or immediately after TENS compared with placebo and without serious adverse events.

This is an impressive review, not least because of its rigorous methodology and the large number of included trials. Its results are clear and convincing. In the words of the authors: “TENS should be considered in a similar manner to rubbing, cooling or warming the skin to provide symptomatic relief of pain via neuromodulation. One advantage of TENS is that users can adjust electrical characteristics to produce a wide variety of TENS sensations such as pulsate and paraesthesiae to combat the dynamic nature of pain. Consequently, patients need to learn how to use a systematic process of trial and error to select electrode positions and electrical characteristics to optimise benefits and minimise problems on a moment to moment basis.”