methodology

The purpose of this recently published survey was to obtain the demographic profile and educational background of chiropractors with paediatric patients on a multinational scale.

A multinational online cross-sectional demographic survey was conducted over a 15-day period in July 2010. The survey was electronically administered via chiropractic associations in 17 countries, using SurveyMonkey for data acquisition, transfer, and descriptive analysis.

The response rate was 10.1%, and 1498 responses were received from 17 countries on 6 continents. Of these, 90.4% accepted paediatric cases. The average practitioner was male (61.1%) and 41.4 years old, had 13.6 years in practice, and saw 107 patient visits per week. Regarding educational background, 63.4% had a bachelor’s degree or higher in addition to their chiropractic qualification, and 18.4% had a postgraduate certificate or higher in paediatric chiropractic.

The authors from the Anglo-European College of Chiropractic (AECC), Bournemouth University, United Kingdom, drew the following conclusion: this is the first study about chiropractors who treat children from the United Arab Emirates, Peru, Japan, South Africa, and Spain. Although the response rate was low, the results of this multinational survey suggest that pediatric chiropractic care may be a common component of usual chiropractic practice on a multinational level for these respondents.

A survey with a response rate of 10%?

An investigation published 9 years after it has been conducted?

Who at the AECC is responsible for controlling the quality of the research output?

Or is this paper perhaps an attempt to get the AECC into the ‘Guinness Book of Records’ for outstanding research incompetence?

But let’s just for a minute pretend that this paper is of acceptable quality. If the finding that ~90% of chiropractors tread kids is approximately correct, one has to be very concerned indeed.

I am not aware of any good evidence that chiropractic care is effective for paediatric conditions. On the contrary, it can do quite a bit of direct harm! To this, we sadly also have to add the indirect harm many chiropractors cause, for instance, by advising parents against vaccinating their kids.

This clearly begs the question: is it not time to stop these charlatans?

What do you think?

The aim of this systematic review was to determine the efficacy of conventional treatments plus acupuncture versus conventional treatments alone for asthma, using a meta-analysis of all published randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

The researchers included all RCTs in which adult and adolescent patients with asthma (age ≥12 years) were divided into conventional treatments plus acupuncture (A+B) and conventional treatments (B). Nine studies were included. The results showed that A+B could improve the symptom response rate and significantly decrease interleukin-6. However, indices of pulmonary function, including the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) failed to be improved with A+B.

The authors concluded that conventional treatments plus acupuncture are associated with significant benefits for adult and adolescent patients with asthma. Therefore, we suggest the use of conventional treatments plus acupuncture for asthma patients.

I am thankful to the authors for confirming my finding that A+B must always be more/better than B alone (the 2nd sentence of their conclusion is, of course, utter nonsense, but I will leave this aside for today). Here is the short abstract of my 2008 article:

In this article, we test the hypothesis that randomized clinical trials of acupuncture for pain with certain design features (A + B versus B) are likely to generate false positive results. Based on electronic searches in six databases, 13 studies were found that met our inclusion criteria. They all suggested that acupuncture is effective (one only showing a positive trend, all others had significant results). We conclude that the ‘A + B versus B’ design is prone to false positive results and discuss the design features that might prevent or exacerbate this problem.

Even though our paper was on acupuncture for pain, it firmly established the principle that A+B is always more than B. Think of it in monetary terms: let’s say we both have $100; now someone gives me $10 more. Who has more cash? Not difficult, is it?

But why do SCAM-fans not get it?

Why do we see trial after trial and review after review ignoring this simple and obvious fact?

I suspect I know why: it is because the ‘A+B vs B’ study-design never generates a negative result!

But that’s cheating!

And isn’t cheating unethical?

My answer is YES!

(If you want to read a more detailed answer, please read our in-depth analysis here)

The present trial evaluated the efficacy of homeopathic medicines of Melissa officinalis (MO), Phytolacca decandra (PD), and the combination of both in the treatment of possible sleep bruxism (SB) in children (grinding teeth during sleep).

Patients (n = 52) (6.62 ± 1.79 years old) were selected based on the parents report of SB. The study comprised a crossover design that included 4 phases of 30-day treatments (Placebo; MO 12c; PD 12c; and MO 12c + PD 12c), with a wash-out period of 15 days between treatments.

At baseline and after each phase, the Visual Analogic Scale (VAS) was used as the primary outcome measure to evaluate the influence of treatments on the reduction of SB. The following additional outcome measures were used: a children’s sleep diary with parent’s/guardian’s perceptions of their children’s sleep quality, the trait of anxiety scale (TAS) to identify changes in children’s anxiety profile, and side effects reports. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Post Hoc LSD test.

Significant reduction of SB was observed in VAS after the use of Placebo (-1.72 ± 0.29), MO (-2.36 ± 0.36), PD (-1.44 ± 0.28) and MO + PD (-2.21 ± 0.30) compared to baseline (4.91 ± 1.87). MO showed better results compared to PD (p = 0.018) and Placebo (p = 0.050), and similar result compared to MO+PD (p = 0.724). The sleep diary results and TAS results were not influenced by any of the treatments. No side effects were observed after treatments.

The authors concluded that MO showed promising results in the treatment of possible sleep bruxism in children, while the association of PD did not improve MO results.

Even if one fully subscribed to the principles of homeopathy, this trial raises several questions:

- Why was it submitted and then published in the journal ‘Phytotherapy’. All the remedies were given as C12 potencies. This has nothing to do with phytomedicine.

- Why was a cross-over design chosen? According to homeopathic theory, a homeopathic treatment has fundamental, long-term effects which last much longer than the wash-out periods between treatment phases. This effectively rules out such a design as a means of testing homeopathy.

- MO is used in phytomedicine to induce sleep and reduce anxiety. According to the homeopathic ‘like cures like’ assumption, this would mean it ought to be used homeopathically to treat sleepiness or for keeping patients awake or for making them anxious. How can it be used for sleep bruxism?

Considering all this, I ask myself: should we trust this study and its findings?

What do you think?

Dengue is a viral infection spread by mosquitoes; it is common in many parts of the world. The symptoms include fever, headache, muscle/joint pain and a red rash. The infection is usually mild and lasts about a week. In rare cases it can be more serious and even life threatening. There’s no specific treatment – except for homeopathy; at least this is what many homeopaths want us to believe.

This article reports the clinical outcomes of integrative homeopathic care in a hospital setting during a severe outbreak of dengue in New Delhi, India, during the period September to December 2015.

Based on preference, 138 patients received a homeopathic medicine along with usual care (H+UC), and 145 patients received usual care (UC) alone. Assessment of thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000/mm3) was the main outcome measure. Kaplan-Meier analysis enabled comparison of the time taken to reach a platelet count of 100,000/mm3.

The results show a statistically significantly greater rise in platelet count on day 1 of follow-up in the H+UC group compared with UC alone. This trend persisted until day 5. The time taken to reach a platelet count of 100,000/mm3 was nearly 2 days earlier in the H+UC group compared with UC alone.

The authors concluded that these results suggest a positive role of adjuvant homeopathy in thrombocytopenia due to dengue. Randomized controlled trials may be conducted to obtain more insight into the comparative effectiveness of this integrative approach.

The design of the study is not able to control for placebo effects. Therefore, the question raised by this study is the following: can an objective parameter like the platelet count be influenced by placebo? The answer is clearly YES.

Why do researchers go to the trouble of conducting such a trial, while omitting both randomisation as well as placebo control? Without such design features the study lacks rigour and its results become meaningless? Why can researchers of Dengue fever run a trial without reporting symptomatic improvements? Could the answer to these questions perhaps be found in the fact that the authors are affiliated to the ‘Central Council for Research in Homoeopathy, New Delhi?

One could argue that this trial – yet another one published in the journal ‘Homeopathy’ – is a waste of resources and patients’ co-operation. Therefore, one might even argue, such a study might be seen as unethical. In any case, I would argue that this study is irrelevant nonsense that should have never seen the light of day.

Power Point therapy (PPT) is not what you might think it is; it is not related to a presentation using power point. Power According to the authors of the so far only study of PPT, it is based on the theories of classic acupuncture, neuromuscular reflexology, and systems theoretical approaches like biocybernetics. It has been developed after four decades of experience by Mr. Gerhard Egger, an Austrian therapist. Hundreds of massage and physiotherapists in Europe were trained to use it, and apply it currently in their practice. The treatment can be easily learned. It is taught by professional PPT therapists to students and patients for self-application in weekend courses, followed by advanced courses for specialists.

The core hypothesis of the PPT system is that various pain syndromes have its origin, among others, in a functional pelvic obliquity. This in turn leads to a static imbalance in the posture of the body. This may result in mechanical strain and possible spinal nerve irritation that may radiate and thus affect dermatomes, myotomes, enterotomes, sclerotomes, and neurotomes of one or more vertebra segments. Therefore, treating reflex zones for the pelvis would reduce and possibly resolve the functional obliquity, improve the statics, and thus cure the pain through improved function. In addition, reflex therapy might be beneficial also in patients with unknown causes of back pain. PPT uses blunt needle tips to apply pressure to specific reflex points on the nose, hand, and feet. PPT has been used for more than 10 years in treating patients with musculoskeletal problems, especially lower back pain.

Sounds more than a little weird?

Yes, I agree.

Perhaps we need some real evidence.

The aim of this RCT was to compare 10 units of PPT of 10 min each, with 10 units of standard physiotherapy of 30 min each. Outcomes were functional scores (Roland Morris Disability, Oswestry, McGill Pain Questionnaire, Linton-Halldén – primary outcome) and health-related quality of life (SF-36), as well as blinded assessments by clinicians (secondary outcome).

Eighty patients consented and were randomized, 41 to PPT, 39 to physiotherapy. Measurements were taken at baseline, after the first and after the last treatment (approximately 5 weeks after enrolment). Multivariate linear models of covariance showed significant effects of time and group and for the quality of life variables also a significant interaction of time by group. Clinician-documented variables showed significant differences at follow-up.

The authors concluded that both physiotherapy and PPT improve subacute low back pain significantly. PPT is likely more effective and should be studied further.

I was tempted to say ‘there is nothing fundamentally wrong with this study’. But then I hesitated and, on second thought, found a few things that do concern me:

- The theory on which PPT is based is not plausible (to put it mildly).

- It would have been easy to conduct a placebo-controlled trial of PPT. The authors justify their odd study design stating this: This was the very first randomized controlled trial of PPT. Therefore, the study has to be considered a pilot. For a pivotal study, a clearly defined primary outcome would have been essential. This was not possible, as no previous experience was able to suggest which outcome would be the best. In my view, this is utter nonsense. Defining the primary outcome of a back pain study is not rocket science; there are plenty of validated measures of pain.

- The study was funded by the Foundation of Natural Sciences and Technical Research in Vaduz, Liechtenstein. I cannot find such an organisation on the Internet.

- The senior author of this study is Prof H Walach who won the prestigious award for pseudoscientist of the year 2012.

- Walach provides no less than three affiliations, including the ‘Change Health Science Institute, Berlin, Germany’. I cannot find such an organisation on the Internet.

- The trial was published in a less than prestigious SCAM journal, ‘Forschende Komplementarmedizin‘ – its editor in-chief: Harald Walach.

So, in view of these concerns, I think PPT might not be nearly as promising as this study implies. Personally, I will wait for an independent replication of Walach’s findings.

This paper notes that, according to the World Naturopathic Federation (WNF), the naturopathic profession is based on two fundamental philosophies of medicine (vitalism and holism) and seven principles of practice (healing power of nature; treat the whole person; treat the cause; first, do no harm; doctor as teacher; health promotion and disease prevention; and wellness). The philosophy, theory, and principles are translated to clinical practice through a range of therapeutic modalities. The WNF has identified seven core modalities: (1) clinical nutrition and diet modification/counselling; (2) applied nutrition (use of dietary supplements, traditional medicines, and natural health care products); (3) herbal medicine; (4) lifestyle counselling; (5) hydrotherapy; (6) homeopathy, including complex homeopathy; and (7) physical modalities (based on the treatment modalities taught and allowed in each jurisdiction, including yoga, naturopathic manipulation, and muscle release techniques).

The ‘scoping’ review was to summarize the current state of the research evidence for whole-system, multi-modality naturopathic medicine. Studies were included, if they met the following criteria:

- Controlled clinical trials, longitudinal cohort studies, observational trials, or case series involving five or more cases presented in any language

- Human studies

- Multi-modality treatment administered by a naturopath (naturopathic clinician, naturopathic physician) as an intervention

- Non-English language studies in which an English title and abstract provided sufficient information to determine effectiveness

- Case series in which five or more individual cases were pooled and authors provided a summative discussion of the cases in the context of naturopathic medicine

- All human research evaluating the effectiveness of naturopathic medicine, where two or more naturopathic modalities are delivered by naturopathic clinicians, were included in the review.

- Case studies of five or more cases were included.

Thirty-three published studies with a total of 9859 patients met inclusion criteria (11 US; 4 Canadian; 6 German; 7 Indian; 3 Australian; 1 UK; and 1 Japanese) across a range of mainly chronic clinical conditions. A majority of the included studies were observational cohort studies (12 prospective and 8 retrospective), with 11 clinical trials and 2 case series. The studies predominantly showed evidence for the efficacy of naturopathic medicine for the conditions and settings in which they were based. Overall, these studies show naturopathic treatment results in a clinically significant benefit for treatment of hypertension, reduction in metabolic syndrome parameters, and improved cardiac outcomes post-surgery.

The authors concluded that to date, research in whole-system, multi-modality naturopathic medicine shows that it is effective for treating cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal pain, type 2 diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, depression, anxiety, and a range of complex chronic conditions. Overall, these studies show naturopathic treatment results in a clinically significant benefit for treatment of hypertension, reduction in metabolic syndrome parameters, and improved cardiac outcomes post-surgery.

Where to start?

There are many issues here to choose from:

- The definition of naturopathy used in this review may be the one of the WHF, but it has little resemblance to the one used elsewhere. German naturopathic doctors, for instance, would not consider homeopathy to be a naturopathic treatment. They would also not, like the WNF does, subscribe to the long-obsolete humoral theory of disease. The only German professional organisation that is a member of the WNF is thus not one of naturopathic doctors but one of Heilpraktiker (the notorious German lay-practitioner created by the Nazis during the Third Reich).

- A review that includes observational studies and even case series, while drawing far-reaching conclusions on therapeutic effectiveness is, in my view, little more than embarrassing pseudo-science. Such studies are unable to differentiate between specific and non-specific therapeutic effects and therefore can tell us nothing about the effectiveness of a treatment.

- A review on a subject such as naturopathy (an approach which, after all, originated in Europe) that excludes studies not published in English (and without an English abstract providing sufficient information to determine effectiveness) is likely to be incomplete.

- The authors call their review a ‘scoping review’; they nevertheless draw conclusions not about the scope but the effectiveness of naturopathy.

- Many of the studies included in this review do, in fact, not comply with the inclusion criteria set by the review-authors.

- The review does not assess or even comment on the risks of naturopathic treatments.

- Several of the included studies are not investigations of naturopathy but of approaches that squarely fall under the umbrella of integrative or alternative medicine.

- Of the 33 studies included, only 5 were RCTs, and none of these was free of major limitations.

- None of the RCTs have been independently replicated.

- There is a remarkable absence of negative trials suggestion a strong influence of bias.

- The review lacks any trace of critical thinking.

- The authors are affiliated to institutions of naturopathy but declare no conflicts of interest.

- No funding source was named but it seems that it was supported by the WNF; their primary goal is to promote and advance the naturopathic profession.

- The review appeared in the notorious Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Prof Dwyer, the founding president of the Australian ‘Friends of Science in Medicine’, said the study damaged Southern Cross University’s reputation. “At the heart of this is the credibility of Southern Cross University,” he said. “There’s been a stand-off between SCU and the rest of the scientific community in Australia for a number of years and there have been challenges to whether they are really upholding the highest standards of evidence-based medicine.” Professor Dwyer also raised questions about the university’s credibility late last year when it accepted a $10 million donation from vitamin company Blackmore’s to establish a National Centre for Naturopathic Medicine.

My conclusion of naturopathy, as defined by the WNF, is that it is an obsolete form of quackery steeped in concepts of vitalism that should be abandoned sooner rather than later. And my conclusion about the new review agrees with Prof Dwyer’s judgement: it is an embarrassment to all concerned.

A new update of the current Cochrane review assessed the benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for the treatment of chronic low back pain. The authors included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effect of spinal manipulation or mobilisation in adults (≥18 years) with chronic low back pain with or without referred pain. Studies that exclusively examined sciatica were excluded.

The effect of SMT was compared with recommended therapies, non-recommended therapies, sham (placebo) SMT, and SMT as an adjuvant therapy. Main outcomes were pain and back specific functional status, examined as mean differences and standardised mean differences (SMD), respectively. Outcomes were examined at 1, 6, and 12 months.

Forty-seven RCTs including a total of 9211 participants were identified. Most trials compared SMT with recommended therapies. In 16 RCTs, the therapists were chiropractors, in 14 they were physiotherapists, and in 5 they were osteopaths. They used high velocity manipulations in 18 RCTs, low velocity manipulations in 12 studies and a combination of the two in 20 trials.

Moderate quality evidence suggested that SMT has similar effects to other recommended therapies for short term pain relief and a small, clinically better improvement in function. High quality evidence suggested that, compared with non-recommended therapies, SMT results in small, not clinically better effects for short term pain relief and small to moderate clinically better improvement in function.

In general, these results were similar for the intermediate and long term outcomes as were the effects of SMT as an adjuvant therapy.

Low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months. Low quality evidence suggested that SMT results in a moderate to strong statistically significant and clinically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically significant better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months.

(Mean difference in reduction of pain at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months (0-100; 0=no pain, 100 maximum pain) for spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) versus recommended therapies in review of the effects of SMT for chronic low back pain. Pooled mean differences calculated by DerSimonian-Laird random effects model.)

About half of the studies examined adverse and serious adverse events, but in most of these it was unclear how and whether these events were registered systematically. Most of the observed adverse events were musculoskeletal related, transient in nature, and of mild to moderate severity. One study with a low risk of selection bias and powered to examine risk (n=183) found no increased risk of an adverse event or duration of the event compared with sham SMT. In one study, the Data Safety Monitoring Board judged one serious adverse event to be possibly related to SMT.

The authors concluded that SMT produces similar effects to recommended therapies for chronic low back pain, whereas SMT seems to be better than non-recommended interventions for improvement in function in the short term. Clinicians should inform their patients of the potential risks of adverse events associated with SMT.

This paper is currently being celebrated (mostly) by chiropractors who think that it vindicates their treatments as being both effective and safe. However, I am not sure that this is entirely true. Here are a few reasons for my scepticism:

- SMT is as good as other recommended treatments for back problems – this may be so but, as no good treatment for back pain has yet been found, this really means is that SMT is as BAD as other recommended therapies.

- If we have a handful of equally good/bad treatments, it stand to reason that we must use other criteria to identify the one that is best suited – criteria like safety and cost. If we do that, it becomes very clear that SMT cannot be named as the treatment of choice.

- Less than half the RCTs reported adverse effects. This means that these studies were violating ethical standards of publication. I do not see how we can trust such deeply flawed trials.

- Any adverse effects of SMT were minor, restricted to the short term and mainly centred on musculoskeletal effects such as soreness and stiffness – this is how some naïve chiro-promoters already comment on the findings of this review. In view of the fact that more than half the studies ‘forgot’ to report adverse events and that two serious adverse events did occur, this is a misleading and potentially dangerous statement and a good example how, in the world of chiropractic, research is often mistaken for marketing.

- Less than half of the studies (45% (n=21/47)) used both an adequate sequence generation and an adequate allocation procedure.

- Only 5 studies (10% (n=5/47)) attempted to blind patients to the assigned intervention by providing a sham treatment, while in one study it was unclear.

- Only about half of the studies (57% (n=27/47)) provided an adequate overview of withdrawals or drop-outs and kept these to a minimum.

- Crucially, this review produced no good evidence to show that SMT has effects beyond placebo. This means the modest effects emerging from some trials can be explained by being due to placebo.

- The lead author of this review (SMR), a chiropractor, does not seem to be free of important conflicts of interest: SMR received personal grants from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), the European Centre for Chiropractic Research Excellence (ECCRE), the Belgian Chiropractic Association (BVC) and the Netherlands Chiropractic Association (NCA) for his position at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He also received funding for a research project on chiropractic care for the elderly from the European Centre for Chiropractic Research and Excellence (ECCRE).

- The second author (AdeZ) who also is a chiropractor received a grant from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), for an independent study on the effects of SMT.

After carefully considering the new review, my conclusion is the same as stated often before: SMT is not supported by convincing evidence for back (or other) problems and does not qualify as the treatment of choice.

“Most of the supplement market is bogus,” Paul Clayton*, a nutritional scientist, told the Observer. “It’s not a good model when you have businesses selling products they don’t understand and cannot be proven to be effective in clinical trials. It has encouraged the development of a lot of products that have no other value than placebo – not to knock placebo, but I want more than hype and hope.” So, Dr Clayton took a job advising Lyma, a product which is currently being promoted as “the world’s first super supplement” at £199 for a one-month’s supply.

Lyma is a dietary supplement that contains a multitude of ingredients all of which are well known and available in many other supplements costing only a fraction of Lyma. The ingredients include:

- kreatinin,

- turmeric,

- Ashwagandha,

- citicoline,

- lycopene,

- vitamin D3.

Apparently, these ingredients are manufactured in special (and patented) ways to optimise their bioavailabity. According to the website, the ingredients of LYMA have all been clinically trialled with proven efficacy at levels provided within the LYMA supplement… Unless the ingredient has been clinically trialled, and peer reviewed there may be limited (if any) benefit to the body. LYMA’s revolutionary formulation is the most advanced and proven super supplement in the world, bringing together eight outstanding ingredients – seven of which are patented – to support health, wellbeing and beauty. Each ingredient has been selected for its efficacy, purity, quality, bioavailability, stability and ultimately, on the results of clinical studies.

The therapeutic claims made for the product are numerous:

- it will improve your hair, skin and nails (80% improvement in skin smoothness, 30% increase in skin moisture, 17% increase in skin elasticity, 12% reduction in wrinkle depth, 47% increase in hair strength & 35% decrease in hair loss)

- it will support energy levels in both the body and the brain (increase in brain membrane turnover by 26% and increase brain energy by 14%),

- it will improve cognitive function,

- it will enhance endurance (cardiorespiratory endurance increased by 13% compared to a placebo),

- it will improve quality of life,

- it will improve sleep (reducing insomnia by 70%),

- it will improve immunity,

- it will reduce inflammation,

- it will improve your memory,

- it will improve osteoporosis (reduce risk of osteoporosis by 37%).

These claims are backed up by 197 clinical trials, we are being told.

If true, this would be truly sensational – but is it true?

I asked the Lyma firm for the 197 original studies, and they very kindly sent me dozens papers which all referred to the single ingredients listed above. I emailed again and asked whether there are any studies of Lyma with all its ingredients in one supplement. Then I was told that they are ‘looking into a trial on the final Lyma formula‘.

I take this to mean that not a single trial of Lyma has been conducted. In this case, how do we be sure the mixture works? How can we know that the 197 studies have not been cherry-picked? How can we be sure that there are no interactions between the active constituents?

The response from Lyma quoted the above-mentioned Dr Paul Clayton stating this: “In regard to LYMA, clinical trials at this stage are not necessary. The whole point of LYMA is that each ingredient has already been extensively trialled, and validated. They have selected the best of the best ingredients, and amalgamated them; to enable consumers to take them all in a convenient format. You can quite easily go out and purchase all the ingredients separately. They aren’t easy to find, and it would mean swallowing up to 12 tablets and capsules a day; but the choice is always yours.”

It’s kind, to leave the choice to us, rather than forcing us to spend £199 each month on the world’s first super-supplement. Very kind indeed!

Having the choice, I might think again.

I might even assemble the world’s maximally evidence-based, extra super-supplement myself, one that is supported by many more than 197 peer-reviewed papers. To not directly compete with Lyma, I could use entirely different ingredients. Perhaps I should take the following five:

- Vitamin C (it has over 61 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Vitanin E (it has over 42 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Collagen (it has over 210 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Coffee (it has over 14 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Aloe vera (it has over 3 000 Medline listed articles to its name).

I could then claim that my extra super-supplement is supported by some 300 000 scientific articles plus 1 000 clinical studies (I am confident I could cherry-pick 1 000 positive trials from the 300 000 papers). Consequently, I would not just charge £199 but £999 for a month’s supply.

But this would be wrong, misleading, even bogus!!!, I hear you object.

On the one hand, I agree.

On the other hand, as Paul Clayton rightly pointed out: Most of the supplement market is bogus.

*If my memory serves me right, I met Paul many years ago when he was a consultant for Boots (if my memory fails me, I might need to order some Lyma).

A recent blog-post pointed out that the usefulness of yoga in primary care is doubtful. Now we have new data to shed some light on this issue.

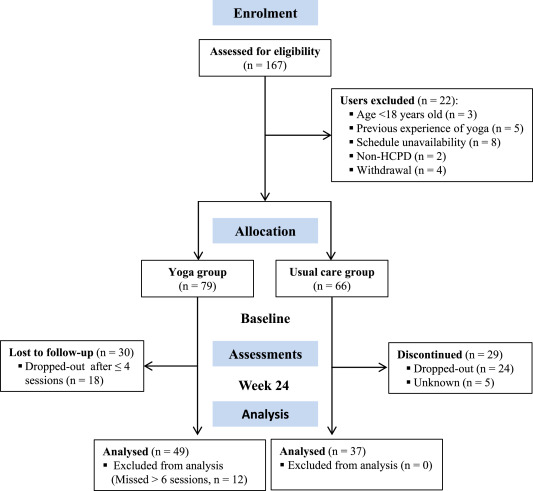

The new paper reports a ‘prospective, longitudinal, quasi-experimental study‘. Yoga group (n= 49) underwent 24-weeks program of one-hour yoga sessions. The control group had no yoga.

Participation was voluntary and the enrolment strategy was based on invitations by health professionals and advertising in the community (e.g., local newspaper, health unit website and posters). Users willing to participate were invited to complete a registration form to verify eligibility criteria.

The endpoints of the study were:

- quality of life,

- psychological distress,

- satisfaction level,

- adherence rate.

The yoga routine consisted of breathing exercises, progressive articular and myofascial warming-up, followed by surya namascar (sun salutation sequence; adapted to the physical condition of each participant), alignment exercises, and postural awareness. Practice also included soft twists of the spine, reversed and balance postures, as well as concentration exercises. During the sessions, the instructor discussed some ethical guidelines of yoga, as for example, non-violence (ahimsa) and truthfulness (satya), to allow the participant to have a safer and integrated practice. In addition, the participants were encouraged to develop their awareness of the present moment and their body sensations, through a continuous process of self-consciousness, keeping a distance between body sensations and the emotional experience. The instructor emphasized the connection between breathing and movement. Each session ended with a guided deep relaxation (yoga nidra; 5–10 min), followed by a meditation practice (5–10 min).

The results of the study showed that the patients in the yoga group experienced a significant improvement in all domains of quality of life and a reduction of psychological distress. Linear regression analysis showed that yoga significantly improved psychological quality of life.

The authors concluded that yoga in primary care is feasible, safe and has a satisfactory adherence, as well as a positive effect on psychological quality of life of participants.

Are the authors’ conclusions correct?

I think not!

Here are some reasons for my judgement:

- The study was far to small to justify far-reaching conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of yoga.

- There were relatively high numbers of drop-outs, as seen in the graph above. Despite this fact, no intention to treat analysis was used.

- There was no randomisation, and therefore the two groups were probably not comparable.

- Participants of the experimental group chose to have yoga; their expectations thus influenced the outcomes.

- There was no attempt to control for placebo effects.

- The conclusion that yoga is safe would require a sample size that is several dimensions larger than 49.

In conclusion, this study fails to show that yoga has any value in primary care.

PS

Oh, I almost forgot: and yoga is also satanic, of course (just like reading Harry Potter!).

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease characterized by recurring flares altered by periods of inactive disease and remission, affecting physical and psychological aspects and quality of life (QoL). The aim of this study was to determine the therapeutic benefits of soft non-manipulative osteopathic techniques in patients with CD.

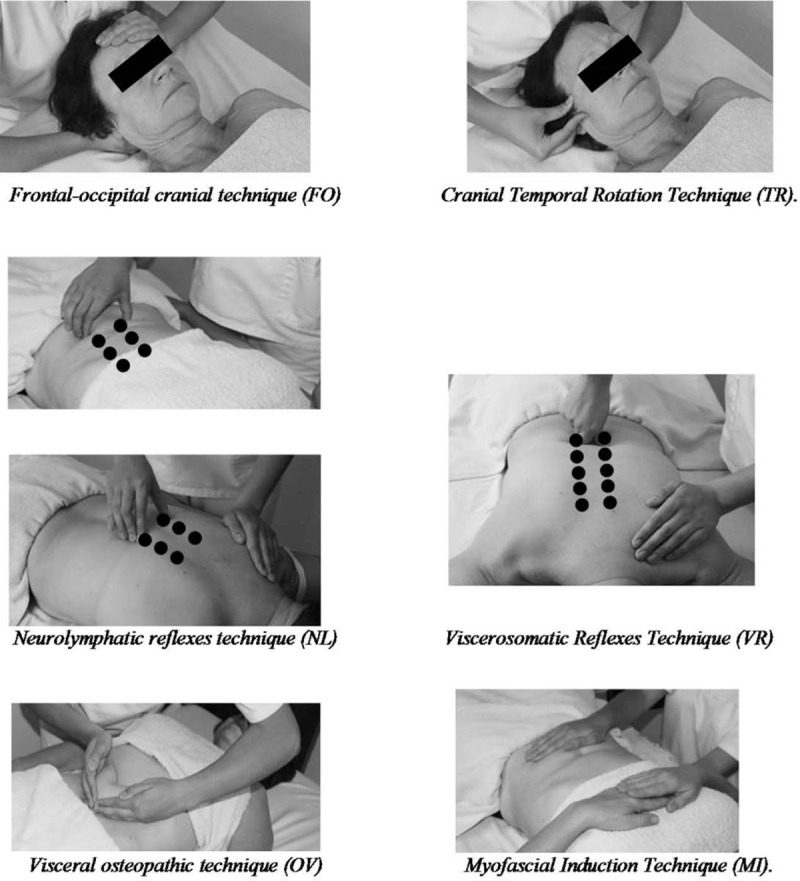

A randomized controlled trial was performed. It included 30 individuals with CD who were divided into 2 groups: 16 in the experimental group (EG) and 14 in the control group (CG). The EG was treated with the 6 manual techniques depicted below. All patients were advised to continue their prescribed medications and diets. The intervention period lasted 30 days (1 session every 10 days). Pain, global quality of life (GQoL) and QoL specific for CD (QoLCD) were assessed before and after the intervention. Anxiety and depression levels were measured at the beginning of the study.

A significant effect was observed of the treatment in both the physical and task subscales of the GQoL and also in the QoLCD but not in pain score. When the intensity of pain was taken into consideration in the analysis of the EG, there was a significantly greater increment in the QoLCD after treatment in people without pain than in those with pain. The improvements in GQoL were independent from the disease status.

The authors concluded that soft, non-manipulative osteopathic treatment is effective in improving overall and physical-related QoL in CD patients, regardless of the phase of the disease. Pain is an important factor that inversely correlates with the improvements in QoL.

Where to begin?

Here are some of the most obvious flaws of this study:

- It was far too small for drawing any far-reaching conclusions.

- Because the sample size was so small, randomisation failed to create two comparable groups.

- Sub-group analyses are based on even smaller samples and thus even less meaningful.

- The authors call their trial a ‘single-blind’ study but, in fact, neither the patients nor the therapists (physiotherapists) were blind.

- The researchers were physiotherapists, their treatments were mostly physiotherapy. It is therefore puzzling why they repeatedly call them ‘osteopathic’.

- It also seems unclear why these and not some other soft tissue techniques were employed.

- The CG did not receive additional treatment at all; no attempt was thus made to control for placebo effects.

- The stated aim to determine the therapeutic benefits… seems to be a clue that this study was never aimed at rigorously testing the effectiveness of the treatments.

My conclusion therefore is (yet again) that poor science has the potential to mislead and thus harm us all.