methodology

As reported, the Bavarian government has set aside almost half a million Euros for research to determine whether the over-use of antibiotics can be reduced by replacing them with homeopathic remedies. Homeopaths in and beyond Germany were delighted, of course, but many experts were bewildered (see also this or this, if you read German).

While the Bavarians are entering the planning stage of this research, I want to elaborate on the question what methodology might be employed for this task. As far as I can see, there are, depending on the precise research questions, various options.

IN VITRO TESTS OF HOMEOPATHICS

The most straight forward way to find out whether homeopathics are an alternative to antibiotics would be to screen them for antibiotic activity. For this, we would take all homeopathic remedies in several potencies that are commonly used, for instance D12 and C30, and add them to bacterial cultures. To cover even part of the range of homeopathic remedies, several thousand such tests would be required. The remedies that show activity in vitro would then be candidates for further clinical tests.

I doubt that this will generate meaningful findings. As homeopaths would probably point out quickly, they never claimed that their remedies have any antibiotic effects. Homeopathics work not via pharmacological mechanisms (there is none), they stimulate the vital force, the immune system, or whatever mystical force you fancy. Faced with the inevitably negative results of in vitro tests, homeopaths would merely shrug their shoulders and say: ‘we told you so’.

ANIMAL MODELS

Thus it might be more constructive to go directly into animal models. Such tests could take several shapes and forms. For instance, scientists could infect animals with a bacterium and subsequently treat one group with a high potency homeopathic remedy and the control group with a placebo. If the homeopathic animals survive, while the controls die, the homeopathic treatment was effective.

Such concepts would run into problems on at least two levels. Firstly, any ethics committee worth its name would refuse to pass such a protocol and argue that it is not ethical to infect and then treat animals with two different types of placebo. Secondly, the homeopathic fraternity would explain that homeopathy must be individualised which cannot be done properly in animals. Faced with the inevitably negative results of such animal studies, homeopaths would merely shrug their shoulders and say: ‘we told you so’.

CLINICAL TRIALS

Homeopathy may, according to some homeopaths, defy in vitro and animal tests, but it is most certainly amenable to being tested in clinical trials. The simplest version of a clinical study would entail randomising a group of patients with bacterial infections – say pneumonia – into receiving either individualised homeopathy or placebo. Possibly, one could add a third group of patients being treated with appropriate antibiotics.

The problem here would again be the ethics; no proper ethic committee would pass such a concept (see above). Another problem might be that even the homeopathic fraternity would oppose such a study. Why? Because all but the most deluded homeopaths know only too well that the result of such a trial would be devastatingly negative for homeopathy.

Therefore, homeopaths are likely to go for a different study design, for instance, one where patients suspected to have a bacterial infection are randomised to two groups of GPs. One group of ‘normal’ GPs would proceed as usual, while the other group are also trained in homeopathy and would be free to give whatever they feel is right for each individual patient. With a bit of luck, the ‘normal’ GPs would over-prescribe antibiotics (because that’s what they are apparently doing routinely), while the homeopathic GPs would often use homeopathics instead.

Such a study would indeed generate a result alleging that the use of homeopathy reduces the use of antibiotics. Of course, to be truly ‘positive’ it would need to exclude any clinical outcome such as time to recovery, because that might not be in favour of homeopathy.

The problem might again be the ethics committee. Assuming they are scientifically switched on, they will see through the futility of a trial designed to produce the desired result. They might also argue that science is not for testing one faulty approach (over-prescribing) against another (homeopathy) and insist that science is about finding the best treatment (which is neither of the two).

There are, of course, many other study designs that could be considered. Generally, they fall into two different categories: if they are rigorous tests of a hypothesis, they are sure to produce a result unfavourable to homeopathy. Such studies will therefore be opposed to by the powerful homeopathic fraternity. If, however, studies are flimsily designed to generate a positive finding, they might be liked by homeopaths, yet rejected by scientists and ethicists.

SURVEYS

A much easier solution to the question ‘does the use of homeopathy reduce the use of antibiotics’ might be to not do a trial at all, but to run a simple survey. For instance, one could retrospectively assess how many antibiotics 100 homeopathic GPs have prescribed during the last year and compare this to the figure of 100 over-prescribing, ‘normal’ GPs. This type of ‘research’ is a sure winner for the homeopaths. Therefore, I predict that they will advocate this or a similarly flawed concept.

Most politicians are scientifically illiterate to such a degree that they might actually agree to finance such a survey and then confuse correlation with causation by triumphantly stating that the use of homeopathy reduces over-prescribing of antibiotics. Few, I fear, will realise that there is only one method for reducing the over-prescribing of antibiotics: remind doctors what they all learnt in medical school, namely to prescribe antibiotics only in cases where they are indicated. And for that we evidently need no homeopathy or other SCAM.

An intercessory prayer (IP) is an intervention characterized by one or more individuals praying for the well-being or a positive outcome of another person. There have been several trials of IP, but the evidence is far from clear-cut. Perhaps this new study will bring clarity?

The goal of this double-blind RCT was to assess the effects of intercessory prayer on psychological, spiritual and biological scores of breast 31 cancer patients who were undergoing radiotherapy (RT). The experimental group was prayed for, while the controla group received no such treatment. The intercessory prayer was performed by a group of six Christians, who prayed daily during 1 h while participant where under RT. The prayers asked for calm, peace, harmony and recovery of health and spiritual well-being of all participants. Data collection was performed in three time points (T0, T1 and T2).

Significant changes were noted in the intra-group analysis, concerning the decrease in spiritual distress score; negative religious/spiritual coping prevailed, while the total religious/spiritual coping increased between the posttest T2 to T0.

The authors concluded that begging a higher being for health recovery is a common practice among people, regardless of their spirituality and religiosity. In this study, this practice was performed through intercessory prayer, which promoted positive health effects, since spiritual distress and negative spiritual coping have reduced. Also, spiritual coping has increased, which means that participants facing difficult situations developed strategies to better cope and solve the problems. Given the results related to the use of intercession prayer, as a complementary therapeutic intervention, holistic nursing care should integrate this intervention, which is included in the Nursing Interventions Classification. Additionally, further evidence and research is needed about the effect of this nursing spiritual intervention in other cultures, in different clinical settings and with larger samples.

The write-up of this study is very poor and most confusing – so much so that I find it hard to make sense of the data provided. If I understand it correctly, the positive findings relate to changes within the experimental group. As RCTs are about compating one group to another, these changes are irrelevant. Therefore (and for several other methodological flaws as well), the conclusion that IP generates positive effects is not warranted by these new findings.

Like all other forms of paranormal healing, IP is implausible and lacks support of clinical effectiveness.

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is a rare but potentially debilitating condition. So far, individualised homeopathy (iHOM) has not been evaluated or reported in any peer-reviewed journal as a treatment option. Here is a recently published case-report of iHOM for BMS.

At the Centre of Complementary Medicine in Bern, Switzerland, a 38-year-old patient with BMS and various co-morbidities was treated with iHOM between July 2014 and August 2018. The treatment involved prescription of individually selected homeopathic single remedies. During follow-up visits, outcome was assessed with two validated questionnaires concerning patient-reported outcomes. To assess whether the documented changes were likely to be associated with the homeopathic intervention, an assessment using the modified Naranjo criteria was performed.

Over an observation period of 4 years, an increasingly beneficial result from iHOM was noted for oral dysaesthesia and pains as well as for the concomitant symptoms.

The authors concluded that considering the multi-factorial aetiology of BMS, a therapeutic approach such as iHOM that integrates the totality of symptoms and complaints of a patient might be of value in cases where an association of psychological factors and the neuralgic complaints is likely.

BMS can have many causes. Some of the possible underlying conditions that can cause BMS include:

- allergies

- hormonal imbalances

- acid reflux

- infections in the mouth

- various medications

- nutritional deficiencies in iron or zinc

- anxiety

- diabetes

Threatemnt of BMS consists of identifying and eliminating the underlying cause. If no cause of BMS can be found, we speak of primary BMS. This condition can be difficult to treat; the following approaches to reduce the severity of the symptoms are being recommended:

- avoiding acidic or spicy foods

- reducing stress

- avoiding any other known food triggers

- exercising regularly

- changing toothpaste

- avoiding mouthwashes containing alcohol

- sucking on ice chips

- avoiding alcohol if it triggers symptoms

- drinking cool liquids throughout the day

- smoking cessation

- eating a balanced diet

- checking medications for potential triggers

The authors of the above case-report state that no efficient treatment of BMS is known. This does not seem to be entirely true. They also seem to think that iHOM benefitted their patient (the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy!). This too is more than doubtful. The natural history of BMS is such that, even if no effective therapy can be found, the condition often disappears after weeks or months.

The authors of the above case-report treated their patient for about 4 years. The devil’s advocate might assume that not only did iHOM contribute nothing to the patient’s improvement, but that it had a detrimental effect on BMS. The data provided are in full agreement with the notion that, without iHOM, the patient would have been symptom-free much quicker.

The use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) are claimed to be associated with preventive health behaviors. However, the role of SCAM use in patients’ health behaviors remains unclear.

This survey aimed to determine the extent to which patients report that SCAM use motivates them to make changes to their health behaviours. For this purpose, a secondary analysis of the 2012 National Health Interview Survey data was undertaken. It involved 10,201 SCAM users living in the US who identified up to three SCAM therapies most important to their health. Analyses assessed the extent to which participants reported that their SCAM use motivated positive health behaviour changes, specifically: eating healthier, eating more organic foods, cutting back/stopping drinking alcohol, cutting back/quitting smoking cigarettes, and/or exercising more regularly.

Overall, 45.4% of SCAM users reported being motivated by SCAM to make positive health behaviour changes, including exercising more regularly (34.9%), eating healthier (31.4%), eating more organic foods (17.2%), reducing/stopping smoking (16.6% of smokers), or reducing/stopping drinking alcohol (8.7% of drinkers). Individual SCAM therapies motivated positive health behaviour changes in 22% (massage) to 81% (special diets) of users. People were more likely to report being motivated to change health behaviours if they were:

- aged 18-64 compared to those aged over 65 years;

- of female gender;

- not in a relationship;

- of Hispanic or Black ethnicity, compared to White;

- reporting at least college education, compared to people with less than high school education;

- without health insurance.

The authors concluded that a sizeable proportion of respondents were motivated by their SCAM use to undertake health behavior changes. CAM practices and practitioners could help improve patients’ health behavior and have potentially significant implications for public health and preventive medicine initiatives; this warrants further research attention.

This seems like an interesting finding! SCAM might be ineffective, but it motivates people to lead a healthier life. Thus SCAM has something to show for itself after all.

Great!

Except, there is another explanation of the results, one that might be much more plausible.

What if some consumers, particularly females who are well-educated and have no health insurance, one day decide that it’s time to do something for their health. Thus they initiate several things:

- they start using SCAM;

- they exercise more regularly;

- they eat more healthily;

- they consume organic food;

- they stop smoking;

- they stop boozing.

The motivation common to all these changes is their determination to do something about their health. Contrary to the authors’ wishful thinking, SCAM has little or even nothing to do with it. The notion was induced by SCAM practitioners who like to think that they play a role in disease prevention, by the leading questions of the interviewer, by recall bias, or by other factors..

What did the wise man say once upon a time?

CORRELATION IS NOT CAUSATION!

Controlled clinical trials are methods for testing whether a treatment works better than whatever the control group is treated with (placebo, a standard therapy, or nothing at all). In order to minimise bias, they ought to be randomised. This means that the allocation of patients to the experimental and the control group must not be by choice but by chance. In the simplest case, a coin might be thrown – heads would signal one, tails the other group.

In so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) where preferences and expectations tend to be powerful, randomisation is particularly important. Without randomisation, the preference of patients for one or the other group would have considerable influence on the result. An ineffective therapy might thus appear to be effective in a biased study. The randomised clinical trial (RCT) is therefore seen as a ‘gold standard’ test of effectiveness, and most researchers of SCAM have realised that they ought to produce such evidence, if they want to be taken seriously.

But, knowingly or not, they often fool the system. There are many ways to conduct RCTs that are only seemingly rigorous but, in fact, are mere tricks to make an ineffective SCAM look effective. On this blog, I have often mentioned the A+B versus B study design which can achieve exactly that. Today, I want to discuss another way in which SCAM researchers can fool us (and even themselves) with seemingly rigorous studies: the de-randomised clinical trial (dRCT).

The trick is to use random allocation to the two study groups as described above; this means the researcher can proudly and honestly present his study as an RCT with all the kudos these three letters seem to afford. And subsequent to this randomisation process, the SCAM researcher simply de-randomises the two groups.

To understand how this is done, we need first to be clear about the purpose of randomisation. If done well, it generates two groups of patients that are similar in all factors that might impact on the results of the study. Perhaps the most obvious factor is disease severity; one could easily use other methods to make sure that both groups of an RCT are equally severely ill. But there are many other factors which we cannot always quantify or even know about. By using randomisation, we make sure that there is an similar distribution of ALL of them in the two study groups, even those factors we are not even aware of.

De-randomisation is thus a process whereby the two previously similar groups are made to differ in terms of any factor that impacts on the results of the trial. In SCAM, this is often surprisingly simple.

Let’s use a concrete example. For our study of spiritual healing, the 5 healers had opted during the planning period of the study to treat both the experimental group and the control group. In the experimental group, they wanted to use their full healing power, while in the control group they would not employ it (switch it off, so to speak). It was clear to me that this was likely to lead to de-randomisation: the healers would have (inadvertently or deliberately) behaved differently towards the two groups of patients. Before and during the therapy, they would have raised the expectation of the verum group (via verbal and non-verbal communication), while sending out the opposite signals to the control group. Thus the two previously equal groups would have become unequal in terms of their expectation. And who can deny that expectation is a major determinant of the outcome? Or who can deny that experienced clinicians can manipulate their patients’ expectation?

For our healing study, we therefore chose a different design and did all we could to keep the two groups comparable. Its findings thus turned out to show that healing is not more effective than placebo (It was concluded that a specific effect of face-to-face or distant healing on chronic pain could not be demonstrated over eight treatment sessions in these patients.). Had we not taken these precautions, I am sure the results would have been very different.

In RCTs of some SCAMs, this de-randomisation is difficult to avoid. Think of acupuncture, for instance. Even when using sham needles that do not penetrate the skin, the therapist is aware of the group allocation. Hoping to prove that his beloved acupuncture can be proven to work, acupuncturists will almost automatically de-randomise their patients before and during the therapy in the way described above. This is, I think, the main reason why some of the acupuncture RCTs using non-penetrating sham devices or similar sham-acupuncture methods suggest that acupuncture is more than a placebo therapy. Similar arguments also apply to many other SCAMs, including for instance chiropractic.

There are several ways of minimising this de-randomisation phenomenon. But the only sure way to avoid this de-randomisation is to blind not just the patient but also the therapists (and to check whether both remained blind throughout the study). And that is often not possible or exceedingly difficult in trials of SCAM. Therefore, I suggest we should always keep de-randomisation in mind. Whenever we are confronted with an RCT that suggest a result that is less than plausible, de-randomisation might be a possible explanation.

On this blog, we have often noted that (almost) all TCM trials from China report positive results. Essentially, this means we might as well discard them, because we simply cannot trust their findings. While being asked to comment on a related issue, it occurred to me that this might be not so much different with Korean acupuncture studies. So, I tried to test the hypothesis by running a quick Medline search for Korean acupuncture RCTs. What I found surprised me and eventually turned into a reminder of the importance of critical thinking.

Even though I found pleanty of articles on acupuncture coming out of Korea, my search generated merely 3 RCTs. Here are their conclusions:

The results of this study show that moxibustion (3 sessions/week for 4 weeks) might lower blood pressure in patients with prehypertension or stage I hypertension and treatment frequency might affect effectiveness of moxibustion in BP regulation. Further randomized controlled trials with a large sample size on prehypertension and hypertension should be conducted.

The results of this study show that acupuncture might lower blood pressure in prehypertension and stage I hypertension, and further RCT need 97 participants in each group. The effect of acupuncture on prehypertension and mild hypertension should be confirmed in larger studies.

Bee venom acupuncture combined with physiotherapy remains clinically effective 1 year after treatment and may help improve long-term quality of life in patients with AC of the shoulder.

So yes, according to this mini-analysis, 100% of the acupuncture RCTs from Korea are positive. But the sample size is tiny and I many not have located all RCTs with my ‘rough and ready’ search.

But what are all the other Korean acupuncture articles about?

Many are protocols for RCTs which is puzzling because some of them are now so old that the RCT itself should long have emerged. Could it be that some Korean researchers publish protocols without ever publishing the trial? If so, why? But most are systematic reviews of RCTs of acupuncture. There must be about one order of magnitude more systematic reviews than RCTs!

Why so many?

Perhaps I can contribute to the answer of this question; perhaps I am even guilty of the bonanza.

In the period between 2008 and 2010, I had several Korean co-workers on my team at Exeter, and we regularly conducted systematic reviews of acupuncture for various indications. In fact, the first 6 systematic reviews include my name. This research seems to have created a trend with Korean acupuncture researchers, because ever since they seem unable to stop themselves publishing such articles.

So far so good, a plethora of systematic reviews is not necessarily a bad thing. But looking at the conclusions of these systematic reviews, I seem to notice a worrying trend: while our reviews from the 2008-2010 period arrived at adequately cautious conclusions, the new reviews are distinctly more positive in their conclusions and uncritical in their tone.

Let me explain this by citing the conclusions of the very first (includes me as senior author) and the very last review (does not include me) currently listed in Medline:

penetrating or non-penetrating sham-controlled RCTs failed to show specific effects of acupuncture for pain control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. More rigorous research seems to be warranted.

Electroacupuncture was an effective treatment for MCI [mild cognitive impairment] patients by improving cognitive function. However, the included studies presented a low methodological quality and no adverse effects were reported. Thus, further comprehensive studies with a design in depth are needed to derive significant results.

Now, you might claim that the evidence for acupuncture has overall become more positive over time, and that this phenomenon is the cause for the observed shift. Yet, I don’t see that at all. I very much fear that there is something else going on, something that could be called the suspension of critical thinking.

Whenever I have asked a Chinese researcher why they only publish positive conclusions, the answer was that, in China, it would be most impolite to publish anything that contradicts the views of the researchers’ peers. Therefore, no Chinese researcher would dream of doing it, and consequently, critical thinking is dangerously thin on the ground.

I think that a similar phenomenon might be at the heart of what I observe in the Korean acupuncture literature: while I always tried to make sure that the conclusions were adequately based on the data, the systematic reviews were ok. When my influence disappeared and the reviews were done exclusively by Korean researchers, the pressure of pleasing the Korean peers (and funders) became dominant. I suggest that this is why conclusions now tend to first state that the evidence is positive and subsequently (almost as an after-thought) add that the primary trials were flimsy. The results of this phenomenon could be serious:

- progress is being stifled,

- the public is being misled,

- funds are being wasted,

- the reputation of science is being tarnished.

Of course, the only right way to express this situation goes something like this:

BECAUSE THE QUALITY OF THE PRIMARY TRIALS IS INADEQUATE, THE EFFECTIVENESS OF ACUPUNCTURE REMAINS UNPROVEN.

Some people seem to think that all so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) is ineffective, harmful or both. And some believe that I am hell-bent to make sure that this message gets out there. I recommend that these guys read my latest book or this 2008 article (sadly now out-dated) and find those (admittedly few) SCAMs that demonstrably generate more good than harm.

The truth, as far as this blog is concerned, is that I am constantly on the lookout to review research that shows or suggests that a therapy is effective or a diagnostic technique is valid (if you see such a paper that is sound and new, please let me know). And yesterday, I have been lucky:

This paper has just been presented at the ESC Congress in Paris.

Its authors are: A Pandey (1), N Huq (1), M Chapman (1), A Fongang (1), P Poirier (2)

(1) Cambridge Cardiac Care Centre – Cambridge – Canada

(2) Université Laval, Faculté de Pharmacie – Laval – Canada

Here is the abstract in full:

Yes, this study was small, too small to draw far-reaching conclusions. And no, we don’t know what precisely ‘yoga’ entailed (we need to wait for the full publication to get this information plus all the other details needed to evaluate the study properly). Yet, this is surely promising: yoga has few adverse effects, is liked by many consumers, and could potentially help millions to reduce their cardiovascular risk. What is more, there is at least some encouraging previous evidence.

But what I like most about this abstract is the fact that the authors are sufficiently cautious in their conclusions and even state ‘if these results are validated…’

SCAM-researchers, please take note!

The journal NATURE has just published an excellent article by Andrew D. Oxman and an alliance of 24 leading scientists outlining the importance and key concepts of critical thinking in healthcare and beyond. The authors state that the Key Concepts for Informed Choices is not a checklist. It is a starting point. Although we have organized the ideas into three groups (claims, comparisons and choices), they can be used to develop learning resources that include any combination of these, presented in any order. We hope that the concepts will prove useful to people who help others to think critically about what evidence to trust and what to do, including those who teach critical thinking and those responsible for communicating research findings.

Here I take the liberty of citing a short excerpt from this paper:

CLAIMS:

Claims about effects should be supported by evidence from fair comparisons. Other claims are not necessarily wrong, but there is an insufficient basis for believing them.

Claims should not assume that interventions are safe, effective or certain.

- Interventions can cause harm as well as benefits.

- Large, dramatic effects are rare.

- We can rarely, if ever, be certain about the effects of interventions.

Seemingly logical assumptions are not a sufficient basis for claims.

- Beliefs alone about how interventions work are not reliable predictors of the presence or size of effects.

- An outcome may be associated with an intervention but not caused by it.

- More data are not necessarily better data.

- The results of one study considered in isolation can be misleading.

- Widely used interventions or those that have been used for decades are not necessarily beneficial or safe.

- Interventions that are new or technologically impressive might not be better than available alternatives.

- Increasing the amount of an intervention does not necessarily increase its benefits and might cause harm.

Trust in a source alone is not a sufficient basis for believing a claim.

- Competing interests can result in misleading claims.

- Personal experiences or anecdotes alone are an unreliable basis for most claims.

- Opinions of experts, authorities, celebrities or other respected individuals are not solely a reliable basis for claims.

- Peer review and publication by a journal do not guarantee that comparisons have been fair.

COMPARISONS:

Studies should make fair comparisons, designed to minimize the risk of systematic errors (biases) and random errors (the play of chance).

Comparisons of interventions should be fair.

- Comparison groups and conditions should be as similar as possible.

- Indirect comparisons of interventions across different studies can be misleading.

- The people, groups or conditions being compared should be treated similarly, apart from the interventions being studied.

- Outcomes should be assessed in the same way in the groups or conditions being compared.

- Outcomes should be assessed using methods that have been shown to be reliable.

- It is important to assess outcomes in all (or nearly all) the people or subjects in a study.

- When random allocation is used, people’s or subjects’ outcomes should be counted in the group to which they were allocated.

Syntheses of studies should be reliable.

- Reviews of studies comparing interventions should use systematic methods.

- Failure to consider unpublished results of fair comparisons can bias estimates of effects.

- Comparisons of interventions might be sensitive to underlying assumptions.

Descriptions should reflect the size of effects and the risk of being misled by chance.

- Verbal descriptions of the size of effects alone can be misleading.

- Small studies might be misleading.

- Confidence intervals should be reported for estimates of effects.

- Deeming results to be ‘statistically significant’ or ‘non-significant’ can be misleading.

- Lack of evidence for a difference is not the same as evidence of no difference.

CHOICES:

What to do depends on judgements about the problem, the relevance (applicability or transferability) of evidence available and the balance of expected benefits, harm and costs.

Problems, goals and options should be defined.

- The problem should be diagnosed or described correctly.

- The goals and options should be acceptable and feasible.

Available evidence should be relevant.

- Attention should focus on important, not surrogate, outcomes of interventions.

- There should not be important differences between the people in studies and those to whom the study results will be applied.

- The interventions compared should be similar to those of interest.

- The circumstances in which the interventions were compared should be similar to those of interest.

Expected pros should outweigh cons.

- Weigh the benefits and savings against the harm and costs of acting or not.

- Consider how these are valued, their certainty and how they are distributed.

- Important uncertainties about the effects of interventions should be reduced by further fair comparisons.

__________________________________________________________________________

END OF QUOTE

I have nothing to add to this, except perhaps to point out how very relevant all of this, of course, is for SCAM and to warmly recommend you study the full text of this brilliant paper.

John Dormandy was a consultant vascular surgeon, researcher, and medical educator best known for innovative work on the diagnosis and management of peripheral arterial disease. He had a leading role in developing, and garnering international support for, uniform guidelines that had a major impact on vascular care among specialists.

The Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus on Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC) was published in 2000.1 Dormandy, a former president of clinical medicine at the Royal Society of Medicine, was the genial force behind it, steering cooperation between medical and surgical society experts in Europe and North America.

“TASC became the standard for describing the severity of the problem that patients had and then defining what options there were to try and treat them,” says Alison Halliday, professor of vascular surgery at Oxford University who worked with Dormandy at St George’s Hospital, London. “It was the first time anybody had tried to get this general view on the complex picture of lower limb artery disease,” she says.

…

After stumbling across this totally unexpected obituary in the BMJ, I was deeply saddened. John was a close friend and mentor; I admired and loved him. He has influenced my life more than anyone else.

Our paths first crossed in 1979 when I applied for a post in his lab at St George’s Hospital, London. Even though I had never really envisaged a career in research, I wanted this job badly. At the time, I had been working as a SHO in a psychiatric hospital and was most unhappy. All I wished at that stage was to get out of psychiatry.

John offered me the position (mainly because of my MD thesis in blood clotting, I think) which was to run his haemorheology (the study of the flow properties of blood) lab. At the time, St Georges consisted of a research tract, a library, a squash court and a mega-building site for the main hospital.

John’s supervision was more than relaxed. As he was a busy surgeon then operating at a different site, I saw him only about once per fortnight, usually for less than 5 minutes. John gave me plenty of time to read (and to play squash!). As he was one of the world leader in haemorheology research, the lab was always full with foreign visitors who wanted to learn our methodologies. We all learnt from each other and had a great time!

After about two years, I had become a budding scientist. John’s mentoring had been minimal but nevertheless most effective. After I left to go back to Germany and finish my clinical training, we stayed in contact. In Munich, I managed to build up my own lab and continued to do haemorheology research. We thus met regularly, published papers and a book together, organised conferences, etc. It was during this time that my former boss became my friend.

Later, he also visited us in Vienna several times, and when I told him that I wanted to come back to England to do research in alternative medicine, he was puzzled but remained supportive (even wrote one of the two references that got me the Exeter job). I think he initially felt this might be a waste of a talent, but he soon changed his mind when he saw what I was up to.

John was one of the most original thinkers I have ever met. His intellect was as sharp as a razor and as fast as lightening. His research activities (>220 Medline listed papers) focussed on haemorheology, vascular surgery and multi-national mega-trials. And, of course, he had a wicket sense of humour. When he had become the clinical director of St George’s, he had to implement a strict no-smoking policy throughout the hospital. Being an enthusiastic cigar smoker, this presented somewhat of a problem for him. The solution was simple: at the entrance of his office John put a sign ‘You are now leaving the premises of St George’s Hospital’.

I saw John last in February this year. My wife and I had invited him for dinner, and when I phoned him to confirm the booking he said: ‘We only need a table for three; Klari (his wife) won’t join us, she died just before Christmas.’ I know how he must have suffered but, in typical Dormandy style, he tried to dissimulate and make light of his bereavement. During dinner he told me about the book he had just published: ‘Not a bestseller, in fact, it’s probably the most boring book you can find’. He then explained the concept of his next book, a history of medicine seen through the medical histories of famous people, and asked, ‘What’s your next one?’, ‘It’s called ‘Don’t believe what you think’, ‘Marvellous title!’, he exclaimed.

We parted that evening saying ‘see you soon’.

I will miss my friend vey badly.

Many so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) traditions have their very own diagnostic techniques, unknown to conventional clinicians. Think, for instance, of:

- iridology,

- applied kinesiology,

- tongue diagnosis,

- pulse diagnosis,

- Kirlean photography,

- live blood cell analysis,

- the Vega test,

- dowsing.

(Those interested in more detail can find a critical assessment of these and other diagnostic SCAM methods in my new book.)

And what about homeopathy?

Yes, homeopathy is also a diagnostic method.

Let me explain.

According to Hahnemann’s classical homeopathy, the homeopath should not be interested in conventional diagnostic labels. Instead, classical homeopaths are focussed on the symptoms and characteristics of the patient. They conduct a lengthy history to learn all about them, and they show little or no interest in a physical examination of their patient or other diagnostic procedures. Once they are confident to have all the information they need, they try to find the optimal homeopathic remedy.

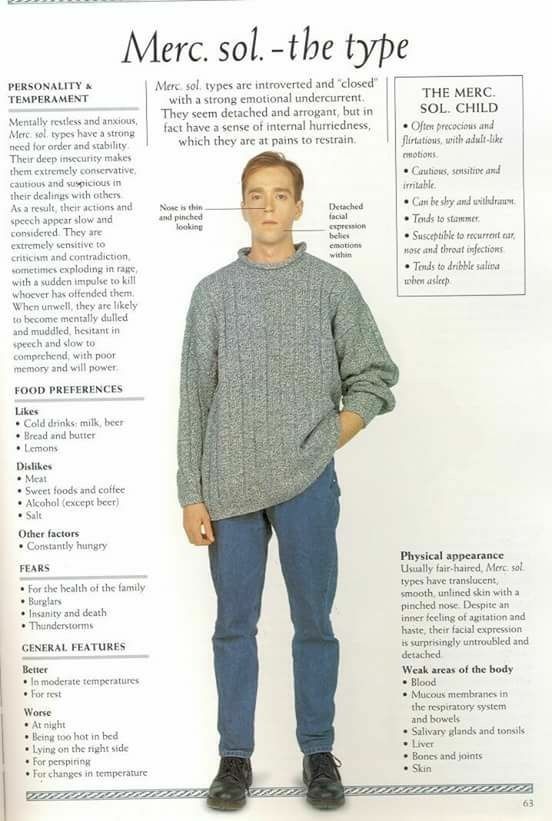

This is done by matching the symptoms with the drug pictures of homeopathic remedies. Any homeopathic drug picture is essentially based on what has been noted in homeopathic provings where healthy volunteers take a remedy and monitor all that symptoms, sensations and feelings they experience subsequently. Here is an example:

The perfect match is what homeopaths thrive to find with their long and tedious procedure of taking a history. And the perfectly matching homeopathic remedy is essentially the homeopathic diagnosis.

The perfect match is what homeopaths thrive to find with their long and tedious procedure of taking a history. And the perfectly matching homeopathic remedy is essentially the homeopathic diagnosis.

Now, here is the thing: most SCAM diagnostic techniques have been tested (and found to be useless), but homeopathy as a diagnostic tool has – as far as I know – never been submitted to any rigorous tests (if you know otherwise, please let me know). And this, of course, begs an important question: is it right – ethical, legal, moral – to use homeopathy without such evidence being available?

The simplest such test would be quite easy to conduct: one would send the same patient to 10 or 20 experienced homeopaths and see how many of them prescribe the same remedy.

Simple! But I shudder to think what such an experiment might reveal.