Monthly Archives: March 2019

A new update of the current Cochrane review assessed the benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for the treatment of chronic low back pain. The authors included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effect of spinal manipulation or mobilisation in adults (≥18 years) with chronic low back pain with or without referred pain. Studies that exclusively examined sciatica were excluded.

The effect of SMT was compared with recommended therapies, non-recommended therapies, sham (placebo) SMT, and SMT as an adjuvant therapy. Main outcomes were pain and back specific functional status, examined as mean differences and standardised mean differences (SMD), respectively. Outcomes were examined at 1, 6, and 12 months.

Forty-seven RCTs including a total of 9211 participants were identified. Most trials compared SMT with recommended therapies. In 16 RCTs, the therapists were chiropractors, in 14 they were physiotherapists, and in 5 they were osteopaths. They used high velocity manipulations in 18 RCTs, low velocity manipulations in 12 studies and a combination of the two in 20 trials.

Moderate quality evidence suggested that SMT has similar effects to other recommended therapies for short term pain relief and a small, clinically better improvement in function. High quality evidence suggested that, compared with non-recommended therapies, SMT results in small, not clinically better effects for short term pain relief and small to moderate clinically better improvement in function.

In general, these results were similar for the intermediate and long term outcomes as were the effects of SMT as an adjuvant therapy.

Low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months. Low quality evidence suggested that SMT results in a moderate to strong statistically significant and clinically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically significant better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months.

(Mean difference in reduction of pain at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months (0-100; 0=no pain, 100 maximum pain) for spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) versus recommended therapies in review of the effects of SMT for chronic low back pain. Pooled mean differences calculated by DerSimonian-Laird random effects model.)

About half of the studies examined adverse and serious adverse events, but in most of these it was unclear how and whether these events were registered systematically. Most of the observed adverse events were musculoskeletal related, transient in nature, and of mild to moderate severity. One study with a low risk of selection bias and powered to examine risk (n=183) found no increased risk of an adverse event or duration of the event compared with sham SMT. In one study, the Data Safety Monitoring Board judged one serious adverse event to be possibly related to SMT.

The authors concluded that SMT produces similar effects to recommended therapies for chronic low back pain, whereas SMT seems to be better than non-recommended interventions for improvement in function in the short term. Clinicians should inform their patients of the potential risks of adverse events associated with SMT.

This paper is currently being celebrated (mostly) by chiropractors who think that it vindicates their treatments as being both effective and safe. However, I am not sure that this is entirely true. Here are a few reasons for my scepticism:

- SMT is as good as other recommended treatments for back problems – this may be so but, as no good treatment for back pain has yet been found, this really means is that SMT is as BAD as other recommended therapies.

- If we have a handful of equally good/bad treatments, it stand to reason that we must use other criteria to identify the one that is best suited – criteria like safety and cost. If we do that, it becomes very clear that SMT cannot be named as the treatment of choice.

- Less than half the RCTs reported adverse effects. This means that these studies were violating ethical standards of publication. I do not see how we can trust such deeply flawed trials.

- Any adverse effects of SMT were minor, restricted to the short term and mainly centred on musculoskeletal effects such as soreness and stiffness – this is how some naïve chiro-promoters already comment on the findings of this review. In view of the fact that more than half the studies ‘forgot’ to report adverse events and that two serious adverse events did occur, this is a misleading and potentially dangerous statement and a good example how, in the world of chiropractic, research is often mistaken for marketing.

- Less than half of the studies (45% (n=21/47)) used both an adequate sequence generation and an adequate allocation procedure.

- Only 5 studies (10% (n=5/47)) attempted to blind patients to the assigned intervention by providing a sham treatment, while in one study it was unclear.

- Only about half of the studies (57% (n=27/47)) provided an adequate overview of withdrawals or drop-outs and kept these to a minimum.

- Crucially, this review produced no good evidence to show that SMT has effects beyond placebo. This means the modest effects emerging from some trials can be explained by being due to placebo.

- The lead author of this review (SMR), a chiropractor, does not seem to be free of important conflicts of interest: SMR received personal grants from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), the European Centre for Chiropractic Research Excellence (ECCRE), the Belgian Chiropractic Association (BVC) and the Netherlands Chiropractic Association (NCA) for his position at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He also received funding for a research project on chiropractic care for the elderly from the European Centre for Chiropractic Research and Excellence (ECCRE).

- The second author (AdeZ) who also is a chiropractor received a grant from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), for an independent study on the effects of SMT.

After carefully considering the new review, my conclusion is the same as stated often before: SMT is not supported by convincing evidence for back (or other) problems and does not qualify as the treatment of choice.

I ought to admit to a conflict of interest regarding today’s post:

I am not a fan of Mr Corbyn!

He fooled us prior to the Referendum claiming he was backing Remain and subsequently campaigned less than half-heartedly for it. Not least thanks to him and his sham of a campaign Leave won the referendum. Subsequently, the UK embarked on a bonanza of self-destruction and a frenzy of xenophobia which changed the UK beyond recognition. Currently, Mr Corbyn is doing the same trick again. He had to concede in the Labour manifesto that his party would eventually support a People’s Vote, and now he bends over backwards to avoid doing anything remotely like it. This strategy, together with his rather non-transparent stance on anti-Semitism does it for me. I could not vote for Corbyn in a million years now.

NOTHING TO DO WITH ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE!, I hear you exclaim.

Yes, you are right – but this has:

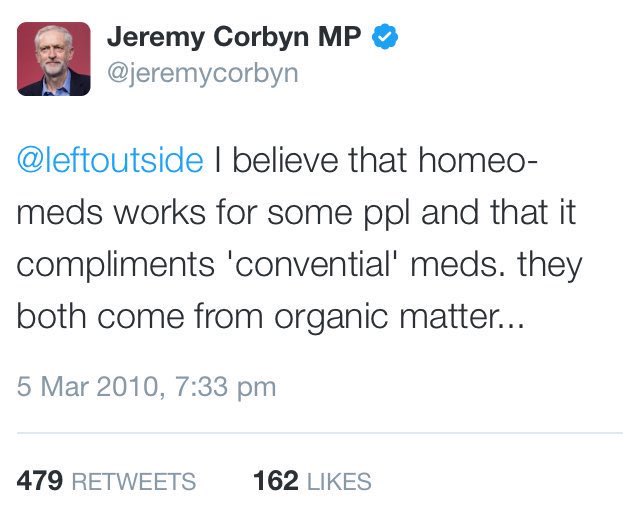

Some time ago, Corbyn tweeted ‘I believe that homeopathy works for some ppl and that it compliments ‘convential’ meds. they both come from organic matter…’

Excuse my frankness, but I find this short tweet embarrassingly stupid (regardless of who authored it).

Apart from two spelling mistakes, it contains several fundamental errors and fallacies:

- Corbyn seems to think that, because some people experience improvement after taking a homeopathic remedy, homeopathy is effective. Does he also believe that the crowing of a cock makes the sun rise in the morning? The statement shows a most irritating lack of understanding as to what constitutes medical evidence and what not. That it was made by a politician makes it only worse.

- Corbyn also tells us that homeopathy is an appropriate adjunct to conventional healthcare. His impression is based on the fact that ‘it works for some people’. This assumption reveals a naivety that is deplorable in a politician who evidently thinks himself sufficiently well-informed to tweet about the matter.

- The final straw is Corbyn’s little afterthought: they both come from organic matter. Many conventional medicines come from inorganic matter. And homeopathic remedies? Yes, many also come from inorganic materials.

Yes, I know, you probably think me a bit pedantic here. As I said, I have strong misgivings against Mr Corbyn.

But, even leaving my prejudice aside, I do think that politicians and other people of influence should comment on issues only after they informed themselves about them sufficiently to make good sense. Otherwise they are in danger to merely disclose their ineptitude in the same way as Corbyn did when he wrote the above tweet.

I stared my Exeter post in October 1993. It took the best part of a year to set up a research team, find rooms etc. So, our research began in earnest only mid 1994. From the very outset, it was clear to me that investigating the risks of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) should be our priority. The reason, I felt, was simple: SCAM was being used a million times every day; therefore it was an ethical imperative to check whether these treatments were as really safe as most people seemed to believe.

In the course of this line of investigation, we did discover many surprises (and lost many friends). One of the very first revelation was that homeopathy might not be harmless. Our initial results on this topic were published in this 1995 article. In view of the still ongoing debate about homeopathy, I’d like to re-publish the short paper here:

Homoeopathic remedies are believed by doctors and patients to be almost totally safe. Is homoeopathic advice safe, for example on the subject of immunization? In order to answer this question, a questionnaire survey was undertaken in 1995 of all 45 homoeopaths listed in the Exeter ‘yellow pages’ business directory. A total of 23 replies (51%) were received, 10 from medically qualified and 13 from non-medically qualified homoeopaths.

The homoeopaths were asked to suggest which conditions they perceived as being most responsive to homoeopathy. The three most frequently cited conditions were allergies (suggested by 10 respondents), gynaecological problems (seven) and bowel problems (five).

They were then asked to estimate the proportion of patients that were referred to them by orthodox doctors and the proportion that they referred to orthodox doctors. The mean estimated percentages were 1 % and 8%, respectively. The 23 respondents estimated that they spent a mean of 73 minutes on the first consultation.

The homoeopaths were asked whether they used or recommended orthodox immunization for children and whether they only used and recommended homoeopathic immunization. Seven of the 10 homoeopaths who were medically qualified recommended orthodox immunization but none of the 13 non-medically qualified homoeopaths did. One non-medically qualified homoeopath only used and recommended homoeopathic immunization.

Homoeopaths have been reported as being against orthodox immunization’ and advocating homoeopathic immunization for which no evidence of effectiveness exists. As yet there has been no attempt in the United Kingdom to monitor homoeopaths’ attitudes in this respect. The above findings imply that there may be a problem. The British homoeopathic doctors’ organization (the Faculty of Homoeopathy) has distanced itself from the polemic of other homoeopaths against orthodox immunization, and editorials in the British Homoeopathic Journal call the abandonment of mass immunization ‘criminally irresponsible’ and ‘most unfortunate, in that it will be seen by most people as irresponsible and poorly based’.’

Homoeopathic remedies may be safe, but do all homoeopaths merit this attribute?

This tiny and seemingly insignificant piece of research triggered debate and research (my group must have published well over 100 papers in the years that followed) that continue to the present day. The debate has spread to many other countries and now involves numerous forms of SCAM other than just homeopathy. It relates to many complex issues such as the competence of SCAM practitioners, their ethical standards, education, regulation, trustworthiness and the risk of neglect.

Looking back, it feels odd that, at least for me, all this started with such a humble investigation almost a quarter of a century ago. Looking towards the future, I predict that we have so far merely seen the tip of the iceberg. The investigation of the risks of SCAM has finally started in earnest and will, I am sure, continue thus leading to a better protection of patients and consumers from charlatans and their bogus claims.

“Most of the supplement market is bogus,” Paul Clayton*, a nutritional scientist, told the Observer. “It’s not a good model when you have businesses selling products they don’t understand and cannot be proven to be effective in clinical trials. It has encouraged the development of a lot of products that have no other value than placebo – not to knock placebo, but I want more than hype and hope.” So, Dr Clayton took a job advising Lyma, a product which is currently being promoted as “the world’s first super supplement” at £199 for a one-month’s supply.

Lyma is a dietary supplement that contains a multitude of ingredients all of which are well known and available in many other supplements costing only a fraction of Lyma. The ingredients include:

- kreatinin,

- turmeric,

- Ashwagandha,

- citicoline,

- lycopene,

- vitamin D3.

Apparently, these ingredients are manufactured in special (and patented) ways to optimise their bioavailabity. According to the website, the ingredients of LYMA have all been clinically trialled with proven efficacy at levels provided within the LYMA supplement… Unless the ingredient has been clinically trialled, and peer reviewed there may be limited (if any) benefit to the body. LYMA’s revolutionary formulation is the most advanced and proven super supplement in the world, bringing together eight outstanding ingredients – seven of which are patented – to support health, wellbeing and beauty. Each ingredient has been selected for its efficacy, purity, quality, bioavailability, stability and ultimately, on the results of clinical studies.

The therapeutic claims made for the product are numerous:

- it will improve your hair, skin and nails (80% improvement in skin smoothness, 30% increase in skin moisture, 17% increase in skin elasticity, 12% reduction in wrinkle depth, 47% increase in hair strength & 35% decrease in hair loss)

- it will support energy levels in both the body and the brain (increase in brain membrane turnover by 26% and increase brain energy by 14%),

- it will improve cognitive function,

- it will enhance endurance (cardiorespiratory endurance increased by 13% compared to a placebo),

- it will improve quality of life,

- it will improve sleep (reducing insomnia by 70%),

- it will improve immunity,

- it will reduce inflammation,

- it will improve your memory,

- it will improve osteoporosis (reduce risk of osteoporosis by 37%).

These claims are backed up by 197 clinical trials, we are being told.

If true, this would be truly sensational – but is it true?

I asked the Lyma firm for the 197 original studies, and they very kindly sent me dozens papers which all referred to the single ingredients listed above. I emailed again and asked whether there are any studies of Lyma with all its ingredients in one supplement. Then I was told that they are ‘looking into a trial on the final Lyma formula‘.

I take this to mean that not a single trial of Lyma has been conducted. In this case, how do we be sure the mixture works? How can we know that the 197 studies have not been cherry-picked? How can we be sure that there are no interactions between the active constituents?

The response from Lyma quoted the above-mentioned Dr Paul Clayton stating this: “In regard to LYMA, clinical trials at this stage are not necessary. The whole point of LYMA is that each ingredient has already been extensively trialled, and validated. They have selected the best of the best ingredients, and amalgamated them; to enable consumers to take them all in a convenient format. You can quite easily go out and purchase all the ingredients separately. They aren’t easy to find, and it would mean swallowing up to 12 tablets and capsules a day; but the choice is always yours.”

It’s kind, to leave the choice to us, rather than forcing us to spend £199 each month on the world’s first super-supplement. Very kind indeed!

Having the choice, I might think again.

I might even assemble the world’s maximally evidence-based, extra super-supplement myself, one that is supported by many more than 197 peer-reviewed papers. To not directly compete with Lyma, I could use entirely different ingredients. Perhaps I should take the following five:

- Vitamin C (it has over 61 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Vitanin E (it has over 42 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Collagen (it has over 210 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Coffee (it has over 14 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Aloe vera (it has over 3 000 Medline listed articles to its name).

I could then claim that my extra super-supplement is supported by some 300 000 scientific articles plus 1 000 clinical studies (I am confident I could cherry-pick 1 000 positive trials from the 300 000 papers). Consequently, I would not just charge £199 but £999 for a month’s supply.

But this would be wrong, misleading, even bogus!!!, I hear you object.

On the one hand, I agree.

On the other hand, as Paul Clayton rightly pointed out: Most of the supplement market is bogus.

*If my memory serves me right, I met Paul many years ago when he was a consultant for Boots (if my memory fails me, I might need to order some Lyma).

Osteopathy is a tricky subject:

- Osteopathic manipulations/mobilisations are advocated mainly for spinal complaints.

- Yet many osteopaths use them also for a myriad of non-spinal conditions.

- Osteopathy comprises two entirely different professions; in the US, osteopaths are very similar to medically trained doctors, and many hardly ever employ osteopathic manual techniques; outside the US, osteopaths are alternative practitioners who use mainly osteopathic techniques and believe in the obsolete gospel of their guru Andrew Taylor Still (this post relates to the latter type of osteopathy).

- The question whether osteopathic manual therapies are effective is still open – even for the indication that osteopaths treat most, spinal complaints.

- Like chiropractors, osteopaths now insist that osteopathy is not a treatment but a profession; the transparent reason for this argument is to gain more wriggle-room when faced with negative evidence regarding they hallmark treatment of osteopathic manipulation/mobilisation.

A new paper authored by osteopaths is an attempt to shed more light on the effectiveness of osteopathy. The aim of this systematic review evaluated the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints. Only randomized controlled trials conducted in high-income Western countries were considered. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts. Primary outcomes included ‘pain’ and ‘functional status’, while secondary outcomes included ‘medication use’ and ‘health status’.

Nineteen studies were included and qualitatively synthesized. Nine studies were from the US, followed by Germany with 7 studies. The majority of studies (n = 13) focused on low back pain.

In general, mixed findings related to the impact of osteopathic care on primary and secondary outcomes were observed. For the primary outcomes, a clear distinction between US and European studies was found, where the latter RCTs reported positive results more frequently. Studies were characterized by substantial methodological differences in sample sizes, number of treatments, control groups, and follow-up.

The authors concluded that “the findings of the current literature review suggested that osteopathic care may improve pain and functional status in patients suffering from spinal complaints. A clear distinction was observed between studies conducted in the US and those in Europe, in favor of the latter. Today, no clear conclusions of the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints can be drawn. Further studies with larger study samples also assessing the long-term impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints are required to further strengthen the body of evidence.”

Some of the most obvious weaknesses of this review include the following:

- In none of the studies employed blinding of patients, care provider or outcome assessor occurred, or it was unclear. Blinding of outcome assessors is easily implemented and should be standard in any RCT.

- In three studies, the study groups differed to some extent at baseline indicating that randomisation was not successful..

- Five studies were derived from the ‘grey literature’ and were therefore not peer-reviewed.

- One study (the UK BEAM trial) employed not just osteopaths but also chiropractors and physiotherapists for administering the spinal manipulations. It is therefore hardly an adequate test of osteopathy.

- The study was funded by an unrestricted grant from the GNRPO, the umbrella organization of the ‘Belgian Professional Associations for Osteopaths’.

Considering this last point, the authors’ honesty in admitting that no clear conclusions of the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints can be drawn is remarkable and deserves praise.

Considering that the evidence for osteopathy is even far worse for non-spinal conditions (numerous trials exist for all sorts of other conditions, but they tend to be flimsy and usually lack independent replications), it is fair to conclude that osteopathy is NOT an evidence-based therapy.

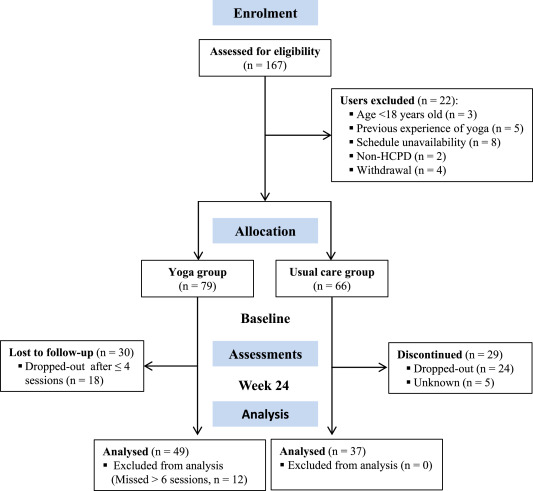

A recent blog-post pointed out that the usefulness of yoga in primary care is doubtful. Now we have new data to shed some light on this issue.

The new paper reports a ‘prospective, longitudinal, quasi-experimental study‘. Yoga group (n= 49) underwent 24-weeks program of one-hour yoga sessions. The control group had no yoga.

Participation was voluntary and the enrolment strategy was based on invitations by health professionals and advertising in the community (e.g., local newspaper, health unit website and posters). Users willing to participate were invited to complete a registration form to verify eligibility criteria.

The endpoints of the study were:

- quality of life,

- psychological distress,

- satisfaction level,

- adherence rate.

The yoga routine consisted of breathing exercises, progressive articular and myofascial warming-up, followed by surya namascar (sun salutation sequence; adapted to the physical condition of each participant), alignment exercises, and postural awareness. Practice also included soft twists of the spine, reversed and balance postures, as well as concentration exercises. During the sessions, the instructor discussed some ethical guidelines of yoga, as for example, non-violence (ahimsa) and truthfulness (satya), to allow the participant to have a safer and integrated practice. In addition, the participants were encouraged to develop their awareness of the present moment and their body sensations, through a continuous process of self-consciousness, keeping a distance between body sensations and the emotional experience. The instructor emphasized the connection between breathing and movement. Each session ended with a guided deep relaxation (yoga nidra; 5–10 min), followed by a meditation practice (5–10 min).

The results of the study showed that the patients in the yoga group experienced a significant improvement in all domains of quality of life and a reduction of psychological distress. Linear regression analysis showed that yoga significantly improved psychological quality of life.

The authors concluded that yoga in primary care is feasible, safe and has a satisfactory adherence, as well as a positive effect on psychological quality of life of participants.

Are the authors’ conclusions correct?

I think not!

Here are some reasons for my judgement:

- The study was far to small to justify far-reaching conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of yoga.

- There were relatively high numbers of drop-outs, as seen in the graph above. Despite this fact, no intention to treat analysis was used.

- There was no randomisation, and therefore the two groups were probably not comparable.

- Participants of the experimental group chose to have yoga; their expectations thus influenced the outcomes.

- There was no attempt to control for placebo effects.

- The conclusion that yoga is safe would require a sample size that is several dimensions larger than 49.

In conclusion, this study fails to show that yoga has any value in primary care.

PS

Oh, I almost forgot: and yoga is also satanic, of course (just like reading Harry Potter!).

The discussion about the value of homeopathy has recently become highly acute in Germany. Once again, it seems that German homeopaths fight for survival with all means imaginable. This can perhaps be better understood in the light of what has happened during the Third Reich. In 1995, I published a paper about this intriguing bit of homeopathic history (British Homoeopathic Journal October 1995, Vol. 84, p. 229). As it has miraculously disappeared from Medline, I take the liberty of re-publishing it here in full and without further comment:

In the early part of the 20th century, there was a strong lay movement of ‘natural health’ in Germany. It is estimated that, when the Nazis took over in 1933, the number of lay practitioners equalled that of physicians. The Nazis jumped on this bandwagon and created the Neue Deutsche Heilkunde (new German medicine)–forced integration of health care to a single body under strict political control [1].

A systematic attempt was orchestrated to scrutinize homoeopathy. The motivation was probably threefold: it fitted the Neue Deutsche Heilkunde concept, it was put forward as a ‘pure German’ line of medicine, and homoeopathy was also seen as potentially a cheap way of keeping the nation healthy, freeing resources for preparatory war efforts. The results have never been published and may be lost for ever. However, an eye- witness report was written after the war by Dr Donner, a homoeopathic physician of high standing. His report, probably not entirely objective, makes fascinating reading [2].

Dr Donner joined the Stuttgart Homoeopathic Hospital in the mid 1930s. He became involved in the German Ministry of Health’s initiatives to scrutinize homoeopathy. Following a detailed study of the literature he expressed profound doubts as to the validity of homoeopathic provings. Experiments to replicate such provings in 1939 showed the importance of the placebo phenomenon and subject/evaluator blinding. His and his colleagues’ results gave no evidence of validity.

A concept by which homoeopathy was to be scrutinized emerged. It foresaw the tests to be supervised by conventional physicians with sufficient knowledge of homoeopathy. About 60 university institutions were to participate. Each team included homoeopaths, toxicologists, pharmacologists and internists. The tests protocols were to be adapted to the special needs of homoeopathy—e.g, freedom of homoeopathic prescription. Donner argues that never before did homoeopathy have such ideal conditions for evaluation. He reports on about 300 planning meetings with staff from the ministry.

Experts were perfectly aware of problems such as the placebo effect and spontaneous remissions and therefore planned large, placebo-controlled trials. These were to be performed on patients with tuberculosis, pernicious anaemia, gonorrhoea and other diseases where homeopaths had claimed to treat successfully.

On the occasion of the 1937 Homoeopathic World Congress in Berlin, Nazi officials decided to start the trials on homoeopathy on a large scale. ‘Hundreds of millions’ of Reichsmark were available. Donner describes several provings and clinical trials in some detail. Without exception, their results yielded no indication for the validity of homoeopathy.

Although there had been previous agreement to the contrary amongst all participants, it was agreed that these negative findings should not be published at this stage, but a new experimental beginning should be sought. Further experiments were planned which could not be concluded due to the outbreak of war.

In 1947, the subject was again discussed by those who were initially involved. The original documents seem to have survived the war. They had not yet been published and are not likely to have been lost or destroyed.

Dr Donner finishes his report by urging the reader to draw the right conclusions. The ‘fiasco’, he maintains, must be blamed not on the individuals involved in these experiments but on the situation inside German homoeopathy. Future evaluations of homoeopathy should be performed to a high scientific standard and without illusions.

Dr Donner’s report is presently being published for the first time [2]. As it is in German, the above summary might be helpful for an international readership.

References

1 Ernst E. Naturheilkunde im Dritten Reich. Dtsch. Arzteblatt 1994 (accepted for publication).

2 Donner. Report to be published in issues 1 5 of Perfusion. Pia Verlag, Nuernberg.

In a previous post, I have tried to explain that someone could be an expert in certain aspects of homeopathy; for instance, one could be an expert:

- in the history of homeopathy,

- in the manufacture of homeopathics,

- in the research of homeopathy.

But can anyone really be an expert in homeopathy in a more general sense?

Are homeopaths experts in homeopathy?

OF COURSE THEY ARE!!!

What is he talking about?, I hear homeopathy-fans exclaim.

Yet, I am not so sure.

Can one be an expert in something that is fundamentally flawed or wrong?

Can one be an expert in flying carpets?

Can one be an expert in quantum healing?

Can one be an expert in clod fusion?

Can one be an expert in astrology?

Can one be an expert in telekinetics?

Can one be an expert in tea-leaf reading?

I am not sure that classical homeopaths can rightfully called experts in classical homeopathy (there are so many forms of homeopathy that, for the purpose of this discussion, I need to focus on the classical Hahnemannian version).

An expert is a person who is very knowledgeable about or skilful in a particular area. An expert in any medical field (say neurology, gynaecology, nephrology or oncology) would need to have sound knowledge and practical skills in areas including:

- organ-specific anatomy,

- organ-specific physiology,

- organ-specific pathophysiology,

- nosology of the medical field,

- disease-specific diagnostics,

- disease-specific etiology,

- disease-specific therapy,

- etc.

None of the listed items apply to classical homeopathy. There are no homeopathic diseases, homeopathy is largely detached from knowledge in anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology, homeopathy disregards the current knowledge of etiology, homeopathy does not apply current criteria of diagnostics, homeopathy offers no rational mode of action for its interventions.

An expert in any medical field would need to:

- deal with facts,

- be able to show the effectiveness of his methods,

- be part of an area that makes progress,

- benefit from advances made elsewhere in medicine,

- would associate with other disciplines,

- understand the principles of evidence-based medicine,

- etc.

None of these features apply to a classical homeopath. Homeopaths substitute facts for fantasy and wishful thinking, homeopaths cannot rely on sound evidence regarding the effectiveness of their therapy, classical homeopaths are not interested in progressing their field but religiously adhere to Hahnemann’s dogma, homeopaths do not benefit from the advances made in other areas of medicine, homeopaths pursue their sectarian activities in near-complete isolation, homeopaths make a mockery of evidence-based medicine.

Collectively, these considerations would seem to indicate that an expert in homeopathy is a contradiction in terms. Either you are an expert, or you are a homeopath. To be both seems an impossibility – or, to put it bluntly, an ‘expert’ in homeopathy is an adept in nonsense and a virtuoso in ignorance.

We have discussed the diagnostic methods used by practitioners of alternative medicine several times before (see for instance here, here, here, here, here and here). Now a new article has been published which sheds more light on this important issue.

The authors point out that the so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) community promote and sell a wide range of tests, many of which are of dubious clinical significance. Many have little or no clinical utility and have been widely discredited, whilst others are established tests that are used for unvalidated purposes.

- The paper mentions the 4 key factors for evaluation of diagnostic methods:

Analytic validity of a test defines its ability to measure accurately and reliably the component of interest. Relevant parameters include analytical accuracy and precision, susceptibility to interferences and quality assurance. - Clinical validity defines the ability to detect or predict the presence or absence of an accepted clinical disease or predisposition to such a disease. Relevant parameters include sensitivity, specificity, and an understanding of how these parameters change in different populations.

- Clinical utility refers to the likelihood that the test will lead to an improved outcome. What is the value of the information to the individual being tested and/or to the broader population?

- Ethical, legal and social implications (ELSI) of a test. Issues include how the test is promoted, how the reasons for testing are explained to the patient, the incidence of false-positive results and incorrect diagnoses, the potential for unnecessary treatment and the cost-effectiveness of testing.

The tests used by SCAM-practitioners range from the highly complex, employing state of the art technology, e.g. heavy metal analysis using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry, to the rudimentary, e.g. live blood cell analysis. Results of ‘SCAM tests’ are often accompanied by extensive clinical interpretations which may recommend, or be used to justify, unnecessary or harmful treatments. There are now a small number of laboratories across the globe that specialize in SCAM testing. Some SCAM laboratories operate completely outside of any accreditation programme whilst others are fully accredited to the standard of established clinical laboratories.

In their review, the authors explore SCAM testing in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia with a focus on the common tests on offer, how they are reported, the evidence base for their clinical application and the regulations governing their use. They also review proposed changed to in-vitro diagnostic device regulations and how these might impact on SCAM testing.

The authors conclude hat the common factor in all these tests is the lack of evidence for clinical validity and utility as used in SCAM practice. This should not be surprising since this is true for SCAM practice in general. Once there is a sound evidence base for an intervention, such as a laboratory test, then it generally becomes incorporated into conventional medical practice.

The paper also discusses possible reasons why SCAM-tests are appealing:

- Adding an element of science to the consultation. Patients know that conventional medicine relies heavily on laboratory diagnostics. If the SCAM practitioner orders laboratory tests, the patient may feel they are benefiting from a scientific approach.

- Producing material diagnostic data to support a diagnosis. SCAM lab reports are well presented in a format that is attractive to patients adding legitimacy to a diagnosis. Tests are often ordered as large profiles of multiple analytes. It follows that this will increase the probability of getting results outside of a given reference interval purely by chance. ‘Abnormal’ results give the SCAM practitioner something to build a narrative around if clinical findings are unclear. This is particularly relevant for patients who have chronic conditions, such as CFS or fibromyalgia where a definitive cause has not been established and treatment options are limited.

- Generating business opportunities using abnormal results. Some practitioners may use abnormal laboratory results to justify further testing, supplements or therapies that they can offer.

- By offering tests that are not available through traditional healthcare services some SCAM practitioners may claim they are offering a unique specialist service that their doctor is unable to provide. This can be particularly appealing to patients with unexplained symptoms for which there are a limited range of evidenced-based investigations and treatments available.

Regulation of SCAM laboratory testing is clearly deficient, the authors of this paper conclude. Where SCAM testing is regulated at all, regulatory authorities primarily evaluate analytical validity of the tests a laboratory offers. Clinical validity and clinical utility are either not evaluated adequately or not evaluated at all and the ethical, legal and social implications of a test may only be considered on a reactive basis when consumers complain about how tests are advertised.

I have always thought that the issue of SCAM tests is hugely important; yet it remains much-neglected. A rubbish diagnosis is likely to result in a rubbish treatment. Unreliable diagnostic methods lead to false-positive and false-negative diagnoses. Both harm the patient. In 1995, I thus published a review that concluded with this warning “alternative” diagnostic methods may seriously threaten the safety and health of patients submitted to them. Orthodox doctors should be aware of the problem and inform their patients accordingly.

Sadly, my warning has so far had no effect whatsoever.

I hope this new paper is more successful.

Guest post by Richard Rawlins

It is 18 years since Health Secretary Alan Milburn launched a scheme for family doctors to prescribe exercise, aerobics, swimming, and yoga for those who are overweight and at risk of strokes, heart disease or suffering from osteoporosis, diabetes or stress. Splendid! But have any benefits resulted? We do not know.

In 2015, Simon Stevens, CEO NHS England, emphasised the importance of NHS staff being cared for: “NHS staff have some of the most critical but demanding jobs in the country. When it comes to supporting the health of our own workforce, frankly the NHS needs to put its own house in order.” He identified “ten leading NHS employers to spearhead a comprehensive initiative to boost NHS staff health at work by committing to ‘six key actions’, including “by establishing and promoting a local physical activity ‘offer’ to staff, such as running, yoga classes, Zumba classes, or competitive sports teams…”

Mr Stevens pointed out that his proposals would cost £5m, but would “help solve the problem of the NHS bill for staff sickness” – then standing at £2.4bn a year.

Good idea. I like to keep fit, and yoga may well help – but is there any evidence it does? Has there been any evaluation of Mr Stevens’ initiative? Has it worked – by any criterion?

More recently, Mr Stevens has climbed aboard the ‘Social Prescribing’ band wagon and declared he would like to see patients provided with yoga, paid for by the NHS.

In January, Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced the need to support a “growing elderly population to stay healthy and independent for longer” with “more social prescribing, empowering people to take greater control and responsibility over their own health through prevention”. And at a ‘Yoga in Healthcare Conference’ in February, Mr Duncan Selbie, chief executive of Public Health England, spoke of extra money promised under the government’s NHS Long Term Plan to fund yoga classes.

Mr Selbie, told doctors and yoga practitioners at the conference: “The evidence is clear … yoga is an evidenced intervention and a strengthening activity that we know works.”

The problem is, Mr Selbie did not provide any evidence in support of his assertions. It is likely there is none. Do not take my word for it – that is the opinion of the US National Center for Complementary and Integrated Health – an institution founded and dedicated to establishing evidence of any benefit from complementary and alternative treatment modalities, and funded to the tune of $164 million p.a.

Promotion for the conference suggested that “The Yoga in Healthcare Alliance (YIHA), the College of Medicine and Integrated Health (CoMIH) and the University of Westminster is collaborating to bridge the worlds of yoga and healthcare with the first ever Yoga in Healthcare Conference.” The YIHA claims it is “working with the NHS to provide yoga to patients.” Its Yoga4Health programme is a 10-week yoga course commissioned by the West London Clinical Commissioning Group, for patients registered at a GP in West London.

In a statement, the YIHA said: “There is significant robust evidence for yoga as an effective ‘mind-body’ medicine that can both prevent and manage chronic health issues and it also delivers significant cost savings to healthcare providers…The College of Medicine will be offering a certificate of attendance to all delegates that can be used towards CPD points.”

On the face of it, that all seems rational and reasonable, but consider, the conference opened with a speech from Dr. Manjunath Nagendra, Chair of the Indian Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy. AYUSH is an “Indian governmental body purposed with developing, education and research in the field of alternative medicines.”

Now it is one thing to cover the background and history of a therapeutic modality at a conference on yoga, but quite another to give respectful house room to a promoter of anachronistic concepts based on vitalism and having no basis in reality. Good luck to those who believe in vitalism, but why is NHS England involved? Is NHS England content to promote alternative medicine? We should be told – perhaps we should all climb on that bandwagon.

Amongst an array of speakers, most with an interest in having alternative medicine paid for by the NHS, Dr Michael Dixon of the CoMIH, spoke on ‘Social Prescribing and Yoga’ and Drs. Patricia Gerbarg and Richard Brown on “The Therapeutic Power of Breath, a Key Public Health Intervention.”

Inevitably, another enjoying a trip on the bandwagon, is the Prince of Wales. In a written address to the conference he advised: “The ancient practice of yoga has proven beneficial effects on both body and mind…For thousands of years, millions of people have experienced yoga’s ability to improve their lives … The development of therapeutic, evidence-based yoga is, I believe, an excellent example of how yoga can contribute to health and healing. This not only benefits the individual, but also conserves precious and expensive health resources for others where and when they are most needed…I will watch the development of therapeutic yoga in the UK with great interest and very much look forward to hearing about the outcomes from your conference.” The Prince claimed yoga classes had “tremendous social benefits and builds discipline, self-reliance and self-care”, which, he said. contributed to improved general health.

The Prince supplied no evidence to support those assertions. No scientific evidence, no economic evidence such as cost-benefit analyses.

The Prince was “delighted” to discover that the conference was examining the health benefits of yoga and claimed it was “the first of its kind in the UK”. Hardly – there have been many conferences on yoga and health, but the semanticists will hide behind the phrase: “…of its kind” – that is, this was the first UK conference involving the ‘College of Medicine and Integrated Health’ together with representatives of NHS institutions. Semantic sophistry.

Originating in India, the principles and practices of yoga developed as one of the six branches of the Vedas – a Hindu spiritual and ascetic discipline, a part of which, including breath control, simple meditation, and the adoption of specific bodily postures, is now more widely practised for health and relaxation. The word yoga comes from the Sanskrit ‘yug’, meaning to yoke or unite. Not fingers touching toes or noses reaching knees, nor the union of mind and body, although, this is a sense commonly applied within the yoga community. The union that the word yoga is referring to is that of uniting individual consciousness and experience of reality with Divine consciousness – a spiritual state perceived when we quiet our five senses and reconnect with the Supreme Self within. That requires faith.

The concept of yoga is inevitably on the agenda of those who perceive a need to foster ‘integration’ and ‘harmony’ – but as oncological surgeon Dr Mark Crislip has pointed out: “If you integrate fantasy with reality, you do not instantiate reality. If you mix cow pie with apple pie it does not make the cow pie taste better, it makes the apple pie worse.”

Back to reality. Academics from Northumbria University have begun a £1.4m four-year study exploring the impact of yoga on older people with multiple long-term health conditions. In the UK, two-thirds of people aged 65+ have multimorbidity – defined as having two or more long-term health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

“Treatments for long-term health conditions account for 70 per cent of NHS expenditure, so researchers want to look at the effectiveness clinically and cost-wise of an adapted yoga programme for older adults with multimorbidity, to reduce reliance on medication.”

Excellent. But for now – the jury is out. Until we do have evidence of the anticipated benefit, we should all bear in mind the view of the Director of the US NICCIH. Commenting on “Yoga for Wellness” Dr Helene Langevin says:

“In a national survey, 94 percent of adults who practiced yoga reported that they did so for wellness-related reasons—such as general wellness and disease prevention or to improve energy – and a large proportion of them perceived benefits from its use. For example, 86 percent said yoga reduced stress, 67 percent said they felt better emotionally, 63 percent said yoga motivated them to exercise more regularly, and 43 percent said yoga motivated them to eat better.”

But what does the science say? Does yoga actually have benefits for wellness? The NCCIH tells us:

“Only a small amount of research has looked at this topic. Not all of the studies have been of high quality, and findings have not been completely consistent. Nevertheless, some preliminary research results suggest that practicing yoga may help people manage stress, improve balance, improve positive aspects of mental health, and adopt healthy eating and physical activity habits.”

“May help” does not mean “it does help”. And whilst TLC is always lovely, and virtually all interventions “may help relieve stress and improve positive aspects of mental health”, the jury is out as to whether yoga actually does have such benefits. And the NCCIH cites “preliminary research…”. “Preliminary” – after some thousands of years?

Shorn of esoteric metaphysical mishmash, yoga may well assist many patients come to terms with their ailments, but the association of NHS institutions with the CoMIH suggest an agenda to have a wider variety of un-evidenced alternative modalities smuggled into the NHS, contrary to policy that NHS healthcare should be based on evidence. Surely that is to be deprecated. NHS England should explain its endorsement for conferences such as this lest all those who are struggling to advance health care on a rational scientific base pack their bags and go home.