A recent blog-post pointed out that the usefulness of yoga in primary care is doubtful. Now we have new data to shed some light on this issue.

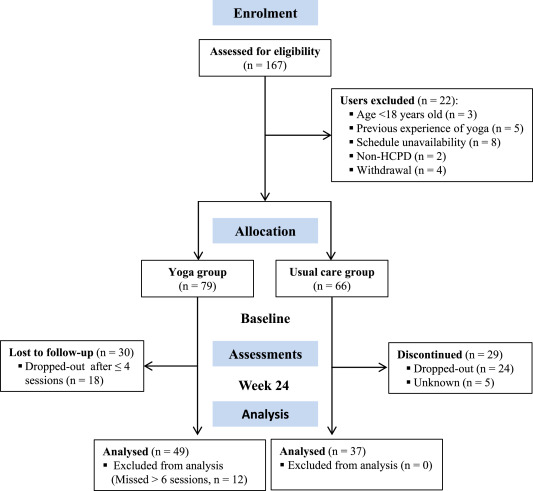

The new paper reports a ‘prospective, longitudinal, quasi-experimental study‘. Yoga group (n= 49) underwent 24-weeks program of one-hour yoga sessions. The control group had no yoga.

Participation was voluntary and the enrolment strategy was based on invitations by health professionals and advertising in the community (e.g., local newspaper, health unit website and posters). Users willing to participate were invited to complete a registration form to verify eligibility criteria.

The endpoints of the study were:

- quality of life,

- psychological distress,

- satisfaction level,

- adherence rate.

The yoga routine consisted of breathing exercises, progressive articular and myofascial warming-up, followed by surya namascar (sun salutation sequence; adapted to the physical condition of each participant), alignment exercises, and postural awareness. Practice also included soft twists of the spine, reversed and balance postures, as well as concentration exercises. During the sessions, the instructor discussed some ethical guidelines of yoga, as for example, non-violence (ahimsa) and truthfulness (satya), to allow the participant to have a safer and integrated practice. In addition, the participants were encouraged to develop their awareness of the present moment and their body sensations, through a continuous process of self-consciousness, keeping a distance between body sensations and the emotional experience. The instructor emphasized the connection between breathing and movement. Each session ended with a guided deep relaxation (yoga nidra; 5–10 min), followed by a meditation practice (5–10 min).

The results of the study showed that the patients in the yoga group experienced a significant improvement in all domains of quality of life and a reduction of psychological distress. Linear regression analysis showed that yoga significantly improved psychological quality of life.

The authors concluded that yoga in primary care is feasible, safe and has a satisfactory adherence, as well as a positive effect on psychological quality of life of participants.

Are the authors’ conclusions correct?

I think not!

Here are some reasons for my judgement:

- The study was far to small to justify far-reaching conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of yoga.

- There were relatively high numbers of drop-outs, as seen in the graph above. Despite this fact, no intention to treat analysis was used.

- There was no randomisation, and therefore the two groups were probably not comparable.

- Participants of the experimental group chose to have yoga; their expectations thus influenced the outcomes.

- There was no attempt to control for placebo effects.

- The conclusion that yoga is safe would require a sample size that is several dimensions larger than 49.

In conclusion, this study fails to show that yoga has any value in primary care.

PS

Oh, I almost forgot: and yoga is also satanic, of course (just like reading Harry Potter!).

The discussion about the value of homeopathy has recently become highly acute in Germany. Once again, it seems that German homeopaths fight for survival with all means imaginable. This can perhaps be better understood in the light of what has happened during the Third Reich. In 1995, I published a paper about this intriguing bit of homeopathic history (British Homoeopathic Journal October 1995, Vol. 84, p. 229). As it has miraculously disappeared from Medline, I take the liberty of re-publishing it here in full and without further comment:

In the early part of the 20th century, there was a strong lay movement of ‘natural health’ in Germany. It is estimated that, when the Nazis took over in 1933, the number of lay practitioners equalled that of physicians. The Nazis jumped on this bandwagon and created the Neue Deutsche Heilkunde (new German medicine)–forced integration of health care to a single body under strict political control [1].

A systematic attempt was orchestrated to scrutinize homoeopathy. The motivation was probably threefold: it fitted the Neue Deutsche Heilkunde concept, it was put forward as a ‘pure German’ line of medicine, and homoeopathy was also seen as potentially a cheap way of keeping the nation healthy, freeing resources for preparatory war efforts. The results have never been published and may be lost for ever. However, an eye- witness report was written after the war by Dr Donner, a homoeopathic physician of high standing. His report, probably not entirely objective, makes fascinating reading [2].

Dr Donner joined the Stuttgart Homoeopathic Hospital in the mid 1930s. He became involved in the German Ministry of Health’s initiatives to scrutinize homoeopathy. Following a detailed study of the literature he expressed profound doubts as to the validity of homoeopathic provings. Experiments to replicate such provings in 1939 showed the importance of the placebo phenomenon and subject/evaluator blinding. His and his colleagues’ results gave no evidence of validity.

A concept by which homoeopathy was to be scrutinized emerged. It foresaw the tests to be supervised by conventional physicians with sufficient knowledge of homoeopathy. About 60 university institutions were to participate. Each team included homoeopaths, toxicologists, pharmacologists and internists. The tests protocols were to be adapted to the special needs of homoeopathy—e.g, freedom of homoeopathic prescription. Donner argues that never before did homoeopathy have such ideal conditions for evaluation. He reports on about 300 planning meetings with staff from the ministry.

Experts were perfectly aware of problems such as the placebo effect and spontaneous remissions and therefore planned large, placebo-controlled trials. These were to be performed on patients with tuberculosis, pernicious anaemia, gonorrhoea and other diseases where homeopaths had claimed to treat successfully.

On the occasion of the 1937 Homoeopathic World Congress in Berlin, Nazi officials decided to start the trials on homoeopathy on a large scale. ‘Hundreds of millions’ of Reichsmark were available. Donner describes several provings and clinical trials in some detail. Without exception, their results yielded no indication for the validity of homoeopathy.

Although there had been previous agreement to the contrary amongst all participants, it was agreed that these negative findings should not be published at this stage, but a new experimental beginning should be sought. Further experiments were planned which could not be concluded due to the outbreak of war.

In 1947, the subject was again discussed by those who were initially involved. The original documents seem to have survived the war. They had not yet been published and are not likely to have been lost or destroyed.

Dr Donner finishes his report by urging the reader to draw the right conclusions. The ‘fiasco’, he maintains, must be blamed not on the individuals involved in these experiments but on the situation inside German homoeopathy. Future evaluations of homoeopathy should be performed to a high scientific standard and without illusions.

Dr Donner’s report is presently being published for the first time [2]. As it is in German, the above summary might be helpful for an international readership.

References

1 Ernst E. Naturheilkunde im Dritten Reich. Dtsch. Arzteblatt 1994 (accepted for publication).

2 Donner. Report to be published in issues 1 5 of Perfusion. Pia Verlag, Nuernberg.

In a previous post, I have tried to explain that someone could be an expert in certain aspects of homeopathy; for instance, one could be an expert:

- in the history of homeopathy,

- in the manufacture of homeopathics,

- in the research of homeopathy.

But can anyone really be an expert in homeopathy in a more general sense?

Are homeopaths experts in homeopathy?

OF COURSE THEY ARE!!!

What is he talking about?, I hear homeopathy-fans exclaim.

Yet, I am not so sure.

Can one be an expert in something that is fundamentally flawed or wrong?

Can one be an expert in flying carpets?

Can one be an expert in quantum healing?

Can one be an expert in clod fusion?

Can one be an expert in astrology?

Can one be an expert in telekinetics?

Can one be an expert in tea-leaf reading?

I am not sure that classical homeopaths can rightfully called experts in classical homeopathy (there are so many forms of homeopathy that, for the purpose of this discussion, I need to focus on the classical Hahnemannian version).

An expert is a person who is very knowledgeable about or skilful in a particular area. An expert in any medical field (say neurology, gynaecology, nephrology or oncology) would need to have sound knowledge and practical skills in areas including:

- organ-specific anatomy,

- organ-specific physiology,

- organ-specific pathophysiology,

- nosology of the medical field,

- disease-specific diagnostics,

- disease-specific etiology,

- disease-specific therapy,

- etc.

None of the listed items apply to classical homeopathy. There are no homeopathic diseases, homeopathy is largely detached from knowledge in anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology, homeopathy disregards the current knowledge of etiology, homeopathy does not apply current criteria of diagnostics, homeopathy offers no rational mode of action for its interventions.

An expert in any medical field would need to:

- deal with facts,

- be able to show the effectiveness of his methods,

- be part of an area that makes progress,

- benefit from advances made elsewhere in medicine,

- would associate with other disciplines,

- understand the principles of evidence-based medicine,

- etc.

None of these features apply to a classical homeopath. Homeopaths substitute facts for fantasy and wishful thinking, homeopaths cannot rely on sound evidence regarding the effectiveness of their therapy, classical homeopaths are not interested in progressing their field but religiously adhere to Hahnemann’s dogma, homeopaths do not benefit from the advances made in other areas of medicine, homeopaths pursue their sectarian activities in near-complete isolation, homeopaths make a mockery of evidence-based medicine.

Collectively, these considerations would seem to indicate that an expert in homeopathy is a contradiction in terms. Either you are an expert, or you are a homeopath. To be both seems an impossibility – or, to put it bluntly, an ‘expert’ in homeopathy is an adept in nonsense and a virtuoso in ignorance.

We have discussed the diagnostic methods used by practitioners of alternative medicine several times before (see for instance here, here, here, here, here and here). Now a new article has been published which sheds more light on this important issue.

The authors point out that the so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) community promote and sell a wide range of tests, many of which are of dubious clinical significance. Many have little or no clinical utility and have been widely discredited, whilst others are established tests that are used for unvalidated purposes.

- The paper mentions the 4 key factors for evaluation of diagnostic methods:

Analytic validity of a test defines its ability to measure accurately and reliably the component of interest. Relevant parameters include analytical accuracy and precision, susceptibility to interferences and quality assurance. - Clinical validity defines the ability to detect or predict the presence or absence of an accepted clinical disease or predisposition to such a disease. Relevant parameters include sensitivity, specificity, and an understanding of how these parameters change in different populations.

- Clinical utility refers to the likelihood that the test will lead to an improved outcome. What is the value of the information to the individual being tested and/or to the broader population?

- Ethical, legal and social implications (ELSI) of a test. Issues include how the test is promoted, how the reasons for testing are explained to the patient, the incidence of false-positive results and incorrect diagnoses, the potential for unnecessary treatment and the cost-effectiveness of testing.

The tests used by SCAM-practitioners range from the highly complex, employing state of the art technology, e.g. heavy metal analysis using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry, to the rudimentary, e.g. live blood cell analysis. Results of ‘SCAM tests’ are often accompanied by extensive clinical interpretations which may recommend, or be used to justify, unnecessary or harmful treatments. There are now a small number of laboratories across the globe that specialize in SCAM testing. Some SCAM laboratories operate completely outside of any accreditation programme whilst others are fully accredited to the standard of established clinical laboratories.

In their review, the authors explore SCAM testing in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia with a focus on the common tests on offer, how they are reported, the evidence base for their clinical application and the regulations governing their use. They also review proposed changed to in-vitro diagnostic device regulations and how these might impact on SCAM testing.

The authors conclude hat the common factor in all these tests is the lack of evidence for clinical validity and utility as used in SCAM practice. This should not be surprising since this is true for SCAM practice in general. Once there is a sound evidence base for an intervention, such as a laboratory test, then it generally becomes incorporated into conventional medical practice.

The paper also discusses possible reasons why SCAM-tests are appealing:

- Adding an element of science to the consultation. Patients know that conventional medicine relies heavily on laboratory diagnostics. If the SCAM practitioner orders laboratory tests, the patient may feel they are benefiting from a scientific approach.

- Producing material diagnostic data to support a diagnosis. SCAM lab reports are well presented in a format that is attractive to patients adding legitimacy to a diagnosis. Tests are often ordered as large profiles of multiple analytes. It follows that this will increase the probability of getting results outside of a given reference interval purely by chance. ‘Abnormal’ results give the SCAM practitioner something to build a narrative around if clinical findings are unclear. This is particularly relevant for patients who have chronic conditions, such as CFS or fibromyalgia where a definitive cause has not been established and treatment options are limited.

- Generating business opportunities using abnormal results. Some practitioners may use abnormal laboratory results to justify further testing, supplements or therapies that they can offer.

- By offering tests that are not available through traditional healthcare services some SCAM practitioners may claim they are offering a unique specialist service that their doctor is unable to provide. This can be particularly appealing to patients with unexplained symptoms for which there are a limited range of evidenced-based investigations and treatments available.

Regulation of SCAM laboratory testing is clearly deficient, the authors of this paper conclude. Where SCAM testing is regulated at all, regulatory authorities primarily evaluate analytical validity of the tests a laboratory offers. Clinical validity and clinical utility are either not evaluated adequately or not evaluated at all and the ethical, legal and social implications of a test may only be considered on a reactive basis when consumers complain about how tests are advertised.

I have always thought that the issue of SCAM tests is hugely important; yet it remains much-neglected. A rubbish diagnosis is likely to result in a rubbish treatment. Unreliable diagnostic methods lead to false-positive and false-negative diagnoses. Both harm the patient. In 1995, I thus published a review that concluded with this warning “alternative” diagnostic methods may seriously threaten the safety and health of patients submitted to them. Orthodox doctors should be aware of the problem and inform their patients accordingly.

Sadly, my warning has so far had no effect whatsoever.

I hope this new paper is more successful.

Guest post by Richard Rawlins

It is 18 years since Health Secretary Alan Milburn launched a scheme for family doctors to prescribe exercise, aerobics, swimming, and yoga for those who are overweight and at risk of strokes, heart disease or suffering from osteoporosis, diabetes or stress. Splendid! But have any benefits resulted? We do not know.

In 2015, Simon Stevens, CEO NHS England, emphasised the importance of NHS staff being cared for: “NHS staff have some of the most critical but demanding jobs in the country. When it comes to supporting the health of our own workforce, frankly the NHS needs to put its own house in order.” He identified “ten leading NHS employers to spearhead a comprehensive initiative to boost NHS staff health at work by committing to ‘six key actions’, including “by establishing and promoting a local physical activity ‘offer’ to staff, such as running, yoga classes, Zumba classes, or competitive sports teams…”

Mr Stevens pointed out that his proposals would cost £5m, but would “help solve the problem of the NHS bill for staff sickness” – then standing at £2.4bn a year.

Good idea. I like to keep fit, and yoga may well help – but is there any evidence it does? Has there been any evaluation of Mr Stevens’ initiative? Has it worked – by any criterion?

More recently, Mr Stevens has climbed aboard the ‘Social Prescribing’ band wagon and declared he would like to see patients provided with yoga, paid for by the NHS.

In January, Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced the need to support a “growing elderly population to stay healthy and independent for longer” with “more social prescribing, empowering people to take greater control and responsibility over their own health through prevention”. And at a ‘Yoga in Healthcare Conference’ in February, Mr Duncan Selbie, chief executive of Public Health England, spoke of extra money promised under the government’s NHS Long Term Plan to fund yoga classes.

Mr Selbie, told doctors and yoga practitioners at the conference: “The evidence is clear … yoga is an evidenced intervention and a strengthening activity that we know works.”

The problem is, Mr Selbie did not provide any evidence in support of his assertions. It is likely there is none. Do not take my word for it – that is the opinion of the US National Center for Complementary and Integrated Health – an institution founded and dedicated to establishing evidence of any benefit from complementary and alternative treatment modalities, and funded to the tune of $164 million p.a.

Promotion for the conference suggested that “The Yoga in Healthcare Alliance (YIHA), the College of Medicine and Integrated Health (CoMIH) and the University of Westminster is collaborating to bridge the worlds of yoga and healthcare with the first ever Yoga in Healthcare Conference.” The YIHA claims it is “working with the NHS to provide yoga to patients.” Its Yoga4Health programme is a 10-week yoga course commissioned by the West London Clinical Commissioning Group, for patients registered at a GP in West London.

In a statement, the YIHA said: “There is significant robust evidence for yoga as an effective ‘mind-body’ medicine that can both prevent and manage chronic health issues and it also delivers significant cost savings to healthcare providers…The College of Medicine will be offering a certificate of attendance to all delegates that can be used towards CPD points.”

On the face of it, that all seems rational and reasonable, but consider, the conference opened with a speech from Dr. Manjunath Nagendra, Chair of the Indian Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy. AYUSH is an “Indian governmental body purposed with developing, education and research in the field of alternative medicines.”

Now it is one thing to cover the background and history of a therapeutic modality at a conference on yoga, but quite another to give respectful house room to a promoter of anachronistic concepts based on vitalism and having no basis in reality. Good luck to those who believe in vitalism, but why is NHS England involved? Is NHS England content to promote alternative medicine? We should be told – perhaps we should all climb on that bandwagon.

Amongst an array of speakers, most with an interest in having alternative medicine paid for by the NHS, Dr Michael Dixon of the CoMIH, spoke on ‘Social Prescribing and Yoga’ and Drs. Patricia Gerbarg and Richard Brown on “The Therapeutic Power of Breath, a Key Public Health Intervention.”

Inevitably, another enjoying a trip on the bandwagon, is the Prince of Wales. In a written address to the conference he advised: “The ancient practice of yoga has proven beneficial effects on both body and mind…For thousands of years, millions of people have experienced yoga’s ability to improve their lives … The development of therapeutic, evidence-based yoga is, I believe, an excellent example of how yoga can contribute to health and healing. This not only benefits the individual, but also conserves precious and expensive health resources for others where and when they are most needed…I will watch the development of therapeutic yoga in the UK with great interest and very much look forward to hearing about the outcomes from your conference.” The Prince claimed yoga classes had “tremendous social benefits and builds discipline, self-reliance and self-care”, which, he said. contributed to improved general health.

The Prince supplied no evidence to support those assertions. No scientific evidence, no economic evidence such as cost-benefit analyses.

The Prince was “delighted” to discover that the conference was examining the health benefits of yoga and claimed it was “the first of its kind in the UK”. Hardly – there have been many conferences on yoga and health, but the semanticists will hide behind the phrase: “…of its kind” – that is, this was the first UK conference involving the ‘College of Medicine and Integrated Health’ together with representatives of NHS institutions. Semantic sophistry.

Originating in India, the principles and practices of yoga developed as one of the six branches of the Vedas – a Hindu spiritual and ascetic discipline, a part of which, including breath control, simple meditation, and the adoption of specific bodily postures, is now more widely practised for health and relaxation. The word yoga comes from the Sanskrit ‘yug’, meaning to yoke or unite. Not fingers touching toes or noses reaching knees, nor the union of mind and body, although, this is a sense commonly applied within the yoga community. The union that the word yoga is referring to is that of uniting individual consciousness and experience of reality with Divine consciousness – a spiritual state perceived when we quiet our five senses and reconnect with the Supreme Self within. That requires faith.

The concept of yoga is inevitably on the agenda of those who perceive a need to foster ‘integration’ and ‘harmony’ – but as oncological surgeon Dr Mark Crislip has pointed out: “If you integrate fantasy with reality, you do not instantiate reality. If you mix cow pie with apple pie it does not make the cow pie taste better, it makes the apple pie worse.”

Back to reality. Academics from Northumbria University have begun a £1.4m four-year study exploring the impact of yoga on older people with multiple long-term health conditions. In the UK, two-thirds of people aged 65+ have multimorbidity – defined as having two or more long-term health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

“Treatments for long-term health conditions account for 70 per cent of NHS expenditure, so researchers want to look at the effectiveness clinically and cost-wise of an adapted yoga programme for older adults with multimorbidity, to reduce reliance on medication.”

Excellent. But for now – the jury is out. Until we do have evidence of the anticipated benefit, we should all bear in mind the view of the Director of the US NICCIH. Commenting on “Yoga for Wellness” Dr Helene Langevin says:

“In a national survey, 94 percent of adults who practiced yoga reported that they did so for wellness-related reasons—such as general wellness and disease prevention or to improve energy – and a large proportion of them perceived benefits from its use. For example, 86 percent said yoga reduced stress, 67 percent said they felt better emotionally, 63 percent said yoga motivated them to exercise more regularly, and 43 percent said yoga motivated them to eat better.”

But what does the science say? Does yoga actually have benefits for wellness? The NCCIH tells us:

“Only a small amount of research has looked at this topic. Not all of the studies have been of high quality, and findings have not been completely consistent. Nevertheless, some preliminary research results suggest that practicing yoga may help people manage stress, improve balance, improve positive aspects of mental health, and adopt healthy eating and physical activity habits.”

“May help” does not mean “it does help”. And whilst TLC is always lovely, and virtually all interventions “may help relieve stress and improve positive aspects of mental health”, the jury is out as to whether yoga actually does have such benefits. And the NCCIH cites “preliminary research…”. “Preliminary” – after some thousands of years?

Shorn of esoteric metaphysical mishmash, yoga may well assist many patients come to terms with their ailments, but the association of NHS institutions with the CoMIH suggest an agenda to have a wider variety of un-evidenced alternative modalities smuggled into the NHS, contrary to policy that NHS healthcare should be based on evidence. Surely that is to be deprecated. NHS England should explain its endorsement for conferences such as this lest all those who are struggling to advance health care on a rational scientific base pack their bags and go home.

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease characterized by recurring flares altered by periods of inactive disease and remission, affecting physical and psychological aspects and quality of life (QoL). The aim of this study was to determine the therapeutic benefits of soft non-manipulative osteopathic techniques in patients with CD.

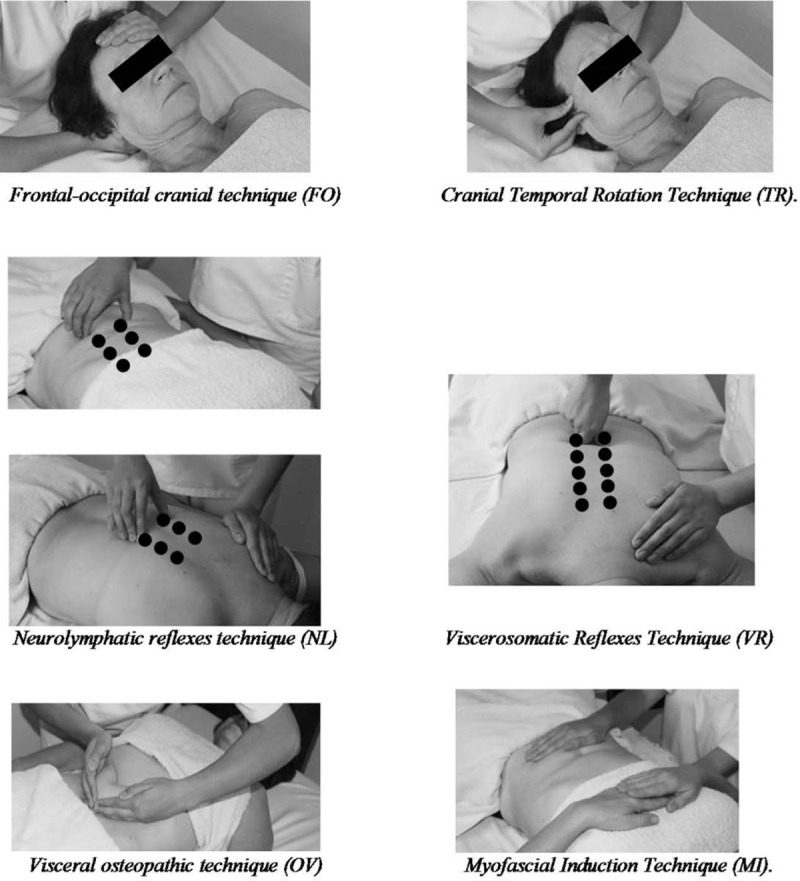

A randomized controlled trial was performed. It included 30 individuals with CD who were divided into 2 groups: 16 in the experimental group (EG) and 14 in the control group (CG). The EG was treated with the 6 manual techniques depicted below. All patients were advised to continue their prescribed medications and diets. The intervention period lasted 30 days (1 session every 10 days). Pain, global quality of life (GQoL) and QoL specific for CD (QoLCD) were assessed before and after the intervention. Anxiety and depression levels were measured at the beginning of the study.

A significant effect was observed of the treatment in both the physical and task subscales of the GQoL and also in the QoLCD but not in pain score. When the intensity of pain was taken into consideration in the analysis of the EG, there was a significantly greater increment in the QoLCD after treatment in people without pain than in those with pain. The improvements in GQoL were independent from the disease status.

The authors concluded that soft, non-manipulative osteopathic treatment is effective in improving overall and physical-related QoL in CD patients, regardless of the phase of the disease. Pain is an important factor that inversely correlates with the improvements in QoL.

Where to begin?

Here are some of the most obvious flaws of this study:

- It was far too small for drawing any far-reaching conclusions.

- Because the sample size was so small, randomisation failed to create two comparable groups.

- Sub-group analyses are based on even smaller samples and thus even less meaningful.

- The authors call their trial a ‘single-blind’ study but, in fact, neither the patients nor the therapists (physiotherapists) were blind.

- The researchers were physiotherapists, their treatments were mostly physiotherapy. It is therefore puzzling why they repeatedly call them ‘osteopathic’.

- It also seems unclear why these and not some other soft tissue techniques were employed.

- The CG did not receive additional treatment at all; no attempt was thus made to control for placebo effects.

- The stated aim to determine the therapeutic benefits… seems to be a clue that this study was never aimed at rigorously testing the effectiveness of the treatments.

My conclusion therefore is (yet again) that poor science has the potential to mislead and thus harm us all.

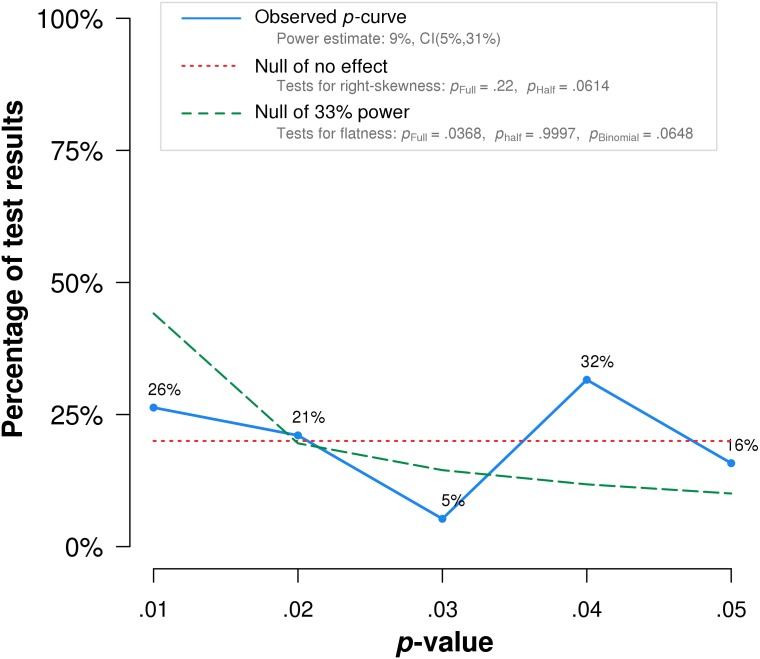

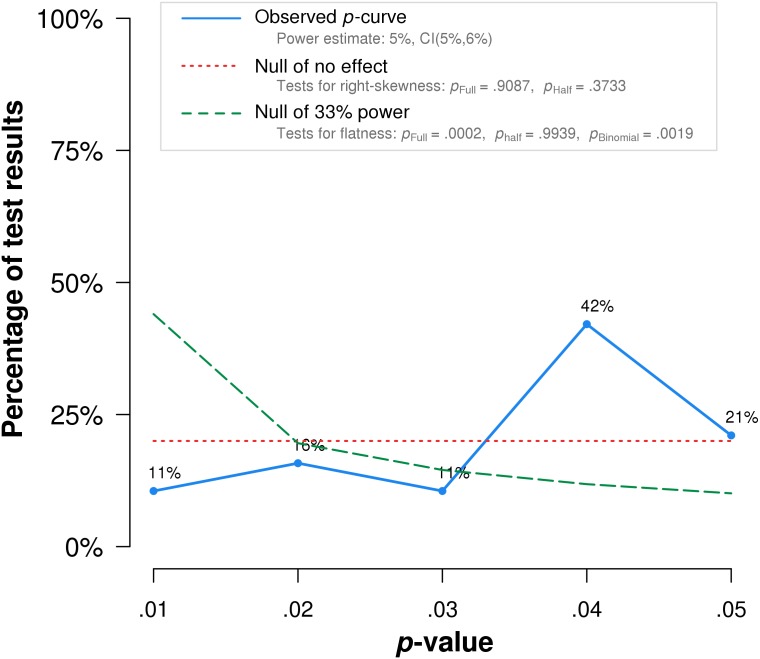

Researchers tend to report only studies that are positive, while leaving negative trials unpublished. This publication bias can mislead us when looking at the totality of the published data. One solution to this problem is the p-curve. A significant p-value indicates that obtaining the result within the null distribution is improbable. The p-curve is the distribution of statistically significant p-values for a set of studies (ps < .05). Because only true effects are expected to generate right-skewed p-curves – containing more low (.01s) than high (.04s) significant p-values – only right-skewed p-curves are diagnostic of evidential value. By telling us whether we can rule out selective reporting as the sole explanation for a set of findings, p-curve offers a solution to the age-old inferential problems caused by file-drawers of failed studies and analyses.

The authors of this article tested the distributions of sets of statistically significant p-values from placebo-controlled studies of homeopathic ultramolecular dilutions. Such dilute mixtures are unlikely to contain a single molecule of an active substance. The researchers tested whether p-curve accurately rejects the evidential value of significant results obtained in placebo-controlled clinical trials of homeopathic ultramolecular dilutions.

Their inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Study is accessible to the authors.

- Study is a clinical trial comparing ultramolecular dilutions to placebo.

- Study is randomized, with randomization method specified.

- Study is double-blinded.

- Study design and methodology result in interpretable findings (e.g., an appropriate statistical test is used).

- Study reports a test statistic for the hypothesis of interest.

- Study reports a discrete p-value or a test statistic from which a p-value can be derived.

- Study reports a p-value independent of other p-values in p-curve.

The first 20 studies, in the order of search output, that met the inclusion criteria were used for analysis.

The researchers found that p-curve analysis accurately rejects the evidential value of statistically significant results from placebo-controlled, homeopathic ultramolecular dilution trials (1st graph below). This result indicates that replications of the trials are not expected to replicate a statistically significant result. A subsequent p-curve analysis was performed using the second significant p-value listed in the studies, if a second p-value was reported, to examine the robustness of initial results. P-curve rejects evidential value with greater statistical significance (2nd graph below). In essence, this seems to indicate that those studies of highly diluted homeopathics that reported positive findings, i. e. homeopathy is better than placebo, are false-positive results due to error, bias or fraud.

The authors’ conclusion: Our results suggest that p-curve can accurately detect when sets of statistically significant results lack evidential value.

The authors’ conclusion: Our results suggest that p-curve can accurately detect when sets of statistically significant results lack evidential value.

True effects with significant non-central distributions would have a greater density of low p-values than high p-values resulting in a right-skewed p-curve (like the dotted green lines in the above graphs). The fact that such a shape is not observed for studies of homeopathy confirms the many analyses previously demonstrating that ULTRAMOLECULAR HOMEOPATHIC REMEDIES ARE PLACEBOS.

As you know, I have repeatedly written about integrative cancer therapy (ICT). Yet, to be honest, I was never entirely sure what it really is; it just did not make sense – not until I saw this announcement. It left little doubt about the nature of ICT.

As it is in German, allow me to translate it for you [the numbers added to the text refer to my comments below]:

ICT is a method of treatment that views humans holistically [1]. The approach is characterised by a synergistic application (integration) of all conventional [the actual term used is a derogatory term coined by Hahnemann to denounce the prevailing medicine of his time], immunological, biological and psychological insights [2]. In this spirit, also personal needs and subjective experiences of disease are accounted for [3]. The aim of this special approach is to offer cancer patients an individualised, interdisciplinary treatment [4].

Besides surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, ICT also includes hormone therapy, hyperthermia, pain management, immunotherapy, normalisation of metabolism, stabilisation of the psyche, physical activity, dietary changes, as well as substitution of vital nutrients [5].

With ICT, the newest discoveries of cancer research are being offered [6], that support the aims of ICT. Therefore, the aims of the ICT doctor include continuous research of the world literature on oncology [7]…

Likewise, one has to start immediately with measures that help prevent metastases and tumour progression [8]. Both the maximization of survival and the optimisation of quality of life ought to be guaranteed [9]. Therefore, the alleviation of the side-effects of the aggressive therapies are one of the most important aims of ICT [10]…

HERE IS THE GERMAN ORIGINAL

Die integrative Krebstherapie ist eine Behandlungsmethode, die den Menschen in seiner Ganzheit sieht und sich dafür einsetzt. Ihre Behandlungsweise ist gekennzeichnet durch die synergetische Anwendung (Integration) aller sinnvollen schulmedizinischen, immunologischen, biologischen und psychologischen Erkenntnisse. In diesem Sinne werden auch die persönlichen Bedürfnisse und die subjektiven Krankheitserlebnisse berücksichtigt. Ziel dieser besonderen Therapie ist es, dass dem Krebspatienten eine individuell eingerichtete und interdisziplinär geplante Behandlung angeboten wird.

Zur integrativen Krebstherapie gehört neben der operativen Tumorbeseitigung, Chemotherapie und Strahlentherapie auch die Hormontherapie, Hyperthermie, Schmerzbeseitigung, Immuntherapie, Normalisierung des Stoffwechsels, Stabilisierung der Psyche, körperliche Aktivierung, Umstellung der Ernährung sowie die Ergänzung fehlender lebensnotwendiger Vitalstoffe.

Mit dieser Behandlungsmethode werden auch die neuesten Entdeckungen der Krebsforschung angeboten, die die Ziele der Integrativen Krebstherapie unterstützen. Deshalb sind die ständigen Recherchen der umfangreichen Ergebnisse der Onkologie-Forschung in der medizinischen Weltliteratur auch Aufgabe der Mediziner in der Integrativen Krebstherapie…

Ebenso sollte auch sofort mit den Maßnahmen begonnen werden, die helfen, dieMetastasen Bildung und Tumorprogredienz zu verhindern. Nicht nur die Maximierung des Überlebens, sondern auch die Optimierung der Lebensqualität sollen gewährleistet werden. Deshalb ist auch die Linderung der Nebenwirkungen der aggressiven Behandlungsmethoden eines der wichtigsten Ziele der Integrativen Krebstherapie….

MY COMMENTS

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

ICT might sound fine to many consumers. I can imagine that it gives confidence to some patients. But it really is nothing other than the adoption of the principles of good conventional cancer care?

No!

But in this case, ICT is just a confidence trick!

It is a confidence trick that allows the trickster to smuggle no end of SCAM into routine cancer care!

Or did I miss something here?

Am I perhaps mistaken?

Please, do tell me!

The American Chiropractic Association (ACA) have just published new guidelines for chiropractors entitled ‘Guidelines for Disaster Service by Doctors of Chiropractic’. Let me show you a few short quotes from this remarkable document:

… Doctors of Chiropractic are uniquely qualified to serve in emergency situations in various capacities.

… their assessment and treatments can be performed in austere environments, on site or at staging areas providing rapid attention to the injury, accelerating healing and often decreasing or substituting the need for pharmaceutical intervention…

Through their education as primary care physicians, Doctors of Chiropractic have demonstrated competence in first aid and resuscitation skills and are able to assess, diagnose and triage so they may serve as first responders in the immediate care of victims at a disaster site…

During and after the disaster, the local Doctors of Chiropractic should interface with the state association and ACA to report on execution of action and outcome of the situation, make suggestions for response to future disasters and report any significant contacts made.

END OF QUOTES

Please allow me to make just 10 corrections and clarifications:

- Chiropractors are not medical doctors; to use the title in any medical context is misleading, to use it in the context of medical emergencies is quite simply reckless.

- Chiropractors are certainly not qualified to serve in emergency situations. This would require a totally different training, experience and set of skills.

- I am not aware of any good evidence that chiropractic can accelerate healing of any medical condition.

- I am also not aware that chiropractic might decrease or substitute the need for pharmaceutical interventions in emergency situations.

- Chiropractors are not primary care physicians.

- Chiropractors have not demonstrated competence in first aid and resuscitation skills.

- Chiropractors are not trained to diagnose the complex and often life-threatening conditions that occur in disaster situations.

- Chiropractors are not trained as first responders in disaster situations.

- Chiropractors are not qualified or trained to report on execution of action and outcome of disaster situation.

- Chiropractors are not qualified or trained to make suggestions for response to future disasters.

The new ACA guidelines are but a thinly disguised attempt to boost chiropractic. They have the potential to endanger lives. And they are an insult to those professionals who have trained hard to acquire the skills to respond to emergencies and disaster situations.

In other words, they are guidelines not for dealing with disasters, but for creating them.

Collagen is a fibrillar protein of the conjunctive and connective tissues in the human body, essentially skin, joints, and bones. Due to its abundance in our bodies, its strength and its relation with skin aging, collagen has gained great interest as an oral dietary supplement as well as an ingredient in cosmetics. Collagen fibres get damaged with the pass of time, losing thickness and strength which has been linked to skin aging phenomena. Collagen can be obtained from natural sources such as plants and animals or by recombinant protein production systems. Because of its increased use, the collagen market is worth billions. The question therefore arises: is it worth it?

This 2019 systematic review assessed all available randomized-controlled trials using collagen supplementation for treatment efficacy regarding skin quality, anti-aging benefits, and potential application in medical dermatology. Eleven studies with a total of 805 patients were included. Eight studies used collagen hydrolysate, 2.5g/d to 10g/d, for 8 to 24 weeks, for the treatment of pressure ulcers, xerosis, skin aging, and cellulite. Two studies used collagen tripeptide, 3g/d for 4 to 12 weeks, with notable improvement in skin elasticity and hydration. Lastly, one study using collagen dipeptide suggested anti-aging efficacy is proportionate to collagen dipeptide content.

The authors concluded that preliminary results are promising for the short and long-term use of oral collagen supplements for wound healing and skin aging. Oral collagen supplements also increase skin elasticity, hydration, and dermal collagen density. Collagen supplementation is generally safe with no reported adverse events. Further studies are needed to elucidate medical use in skin barrier diseases such as atopic dermatitis and to determine optimal dosing regimens.

These conclusions are similar to those of a similar but smaller review of 2015 which concluded that the oral supplementation with collagen peptides is efficacious to improve hallmarks of skin aging.

And what about the many other claims that are currently being made for oral collagen?

A 2006 review of collagen for osteoarthritis concluded that a growing body of evidence provides a rationale for the use of collagen hydrolysate for patients with OA. It is hoped that ongoing and future research will clarify how collagen hydrolysate provides its clinical effects and determine which populations are most appropriate for treatment with this supplement. For other indication, the evidence seems less conclusive.

So, what should we make of this collective evidence. My interpretation is that, of course, there are caveats. For instance, most studies are small and not as rigorous as one would hope. But the existing evidence is nevertheless intriguing (and much more compelling than that for most other supplements). Moreover, there seem to be very few adverse effects with oral usage (don’t inject the stuff for cosmetic purposes, as often recommended!). Therefore, I feel that collagen might be one of the few dietary supplements worth keeping an eye on.