risk/benefit

Practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) often argue against treating back problems with drugs. They also frequently defend their own therapy by claiming it is backed by published guidelines. So, what should we think about guidelines for the management of back pain?

This systematic review was aimed at:

- systematically evaluating the literature for clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) that included the pharmaceutical management of non-specific LBP;

- appraising the methodological quality of the CPGs;

- qualitatively synthesizing the recommendations with the intent to inform non-prescribing providers who manage LBP.

The authors searched PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, Index to Chiropractic Literature, AMED, CINAHL, and PEDro to identify CPGs that described the management of mechanical LBP in the prior five years. Two investigators independently screened titles and abstracts and potentially relevant full text were considered for eligibility. Four investigators independently applied the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument for critical appraisal. Data were extracted for pharmaceutical intervention, the strength of recommendation, and appropriateness for the duration of LBP.

Only nine guidelines with global representation met the eligibility criteria. These CPGs addressed pharmacological treatments with or without non-pharmacological treatments. All CPGs focused on the management of acute, chronic, or unspecified duration of LBP. The mean overall AGREE II score was 89.3% (SD 3.5%). The lowest domain mean score was for applicability, 80.4% (SD 5.2%), and the highest was Scope and Purpose, 94.0% (SD 2.4%). There were ten classifications of medications described in the included CPGs: acetaminophen, antibiotics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, oral corticosteroids, skeletal muscle relaxants (SMRs), and atypical opioids.

The authors concluded that nine CPGs, included ten medication classes for the management of LBP. NSAIDs were the most frequently recommended medication for the treatment of both acute and chronic LBP as a first line pharmacological therapy. Acetaminophen and SMRs were inconsistently recommended for acute LBP. Meanwhile, with less consensus among CPGs, acetaminophen and antidepressants were proposed as second-choice therapies for chronic LBP. There was significant heterogeneity of recommendations within many medication classes, although oral corticosteroids, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, and antibiotics were not recommended by any CPGs for acute or chronic LBP.

Oddly, this review was published by chiros in a chiro journal. The authors mention that nearly all guidelines the included CPGs recommended non-pharmacological treatments for non-specific LBP, however it was not always delineated as to precede or be used in conjunction with pharmacological intervention.

I find the review interesting because I think it suggests that:

- CPGs are not the most reliable form of evidence. Their guidance depends on how up-to-date they are and on the identity and purpose of the authors.

- Guidelines are therefore often contradictory.

- Back pain is a symptom for which currently no optimal treatment exists.

- The most reliable evidence will rarely come from CPGs but from rigorous, up-to-date, independent systematic reviews such as those from the Cochrane Collaboration.

So, the next time chiropractors osteopaths, acupuncturists, etc. tell you “BUT MY THERAPY IS RECOMMENDED IN THE GUIDELINES”, please take it with a pinch of salt.

Ayush-64 is an Ayurvedic formulation, developed by the Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS), the apex body for research in Ayurveda under the Ministry of Ayush. Originally developed in 1980 for the management of Malaria, this drug has now been repurposed for COVID-19 as its ingredients showed notable antiviral, immune-modulator, and antipyretic properties. Its ingredients are:

| Alstonia scholaris R. Br. Aqueous extract of (Saptaparna) | Bark-1 part |

| Picrorhiza Kurroa Royle Aqueous extract of (Kutki) | Rhizome-1 part |

| Swertia chirata Buch-Ham. Aqueous extract of (Chirata) | Whole plant-1 part |

| Caesalphinia crista, Linn. Fine powder of seed (Kuberaksha) | Pulp-2 parts |

The crucial question, of course, is does AYUSH-64 work?

An open-label randomized controlled parallel-group trial was conducted at a designated COVID care centre in India with 80 patients diagnosed with mild to moderate COVID-19 and randomized into two groups. Participants in the AYUSH-64 add-on group (AG) received AYUSH-64 two tablets (500 mg each) three times a day for 30 days along with standard conventional care. The control group (CG) received standard care alone.

The outcome measures were:

- the proportion of participants who attained clinical recovery on days 7, 15, 23, and 30,

- the proportion of participants with negative RT-PCR assay for COVID-19 at each weekly time point,

- change in pro-inflammatory markers,

- metabolic functions,

- HRCT chest (CO-RADS category),

- the incidence of Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR)/Adverse Event (AE).

Out of 80 participants, 74 (37 in each group) contributed to the final analysis. A significant difference was observed in clinical recovery in the AG (p < 0.001 ) compared to CG. The mean duration for clinical recovery in AG (5.8 ± 2.67 days) was significantly less compared to CG (10.0 ± 4.06 days). Significant improvement in HRCT chest was observed in AG (p = 0.031) unlike in CG (p = 0.210). No ADR/SAE was observed or reported in AG.

The authors concluded that AYUSH-64 as adjunct to standard care is safe and effective in hastening clinical recovery in mild to moderate COVID-19. The efficacy may be further validated by larger multi-center double-blind trials.

I do object to these conclusions for several reasons:

- The study cannot possibly determine the safety of AYUSH-64.

- Even for assessing its efficacy, it was too small.

- The trial design followed the often-discussed A+B vs B concept and is thus prone to generate false-positive results.

I believe that it is highly irresponsible, during a medical crisis like ours, to conduct studies that can only produce unreliable findings. If there is a real possibility that a therapy might work, we do need to test it, but we should take great care that the test is rigorous enough to generate reliable results. This, I think, is all the more true, if – like in the present case – the study was done with governmental support.

Anyone who has followed this blog for a while will know that advocates of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) are either in complete denial about the risks of SCAM or they do anything to trivialize them. Here is a dialogue between a SCAM proponent (P) and a scientist (S) that is aimed at depicting this situation. The conversation is fictitious, of course, but it is nevertheless based on years of experience in discussing these issues with practitioners of various types of SCAM. As we shall see, the arguments turn out to be perfectly circular.

P: My therapy is virtually free of risks.

S: How can you be so sure?

P: I am practicing it for decades and have never seen a single problem.

S: That could have several reasons; perhaps the patients who experience problems did simply not come back.

P: I find this unlikely.

S: I don’t, and I know of reports where patients had serious complications after the type of SCAM you practice.

P: These are isolated case reports. They do not amount to evidence.

S: How do you know they are isolated?

P: They must be isolated because, in the many clinical trials of my therapy available to date, you will not find any evidence of serious adverse effects.

S: That is true, but it has been repeatedly shown that these trials regularly fail to mention side effects altogether.

P: That’s because there aren’t any.

S: Not quite, clinical trials should always mention adverse effects, and if there were none, they should mention this too.

P: So, you admit that you have no evidence that my therapy causes adverse effects.

S: The thing is, I don’t need such evidence. It is you, the practitioners of this therapy, who should provide evidence that your treatments are safe.

P: We did! The complete absence of reports of side effects constitutes that evidence.

S: Except, there is some evidence. I already told you that there are several case reports of serious problems.

P: But case reports are anecdotes; they are no evidence.

S: Look, here is a systematic review of all the case reports. You cannot possibly deny that this is a concern.

P: It’s still merely a bunch of anecdotes, nothing more.

S: Only because your profession does nothing about it.

P: What do you think we need to do about it?

S: Like other professions, you need to systematically record adverse effects.

P: How would that help?

S: It would give us a rough indication of the size and severity of the problem.

P: This sounds expensive and complicated to organize.

S: Perhaps, but it is necessary if you want to be sure that your therapy is safe.

P: But we are sure already!

S: No, you believe it, but you don’t know it.

P: You are getting on my nerves with your obsession. Don’t you know that the true danger in healthcare is the adverse effects of pharmaceutical drugs?

S: But these drugs are also effective.

P: Are you saying my therapy isn’t?

S: What I am saying is that the drugs you claim to be dangerous do more good than harm, while this is not at all clear with your SCAM.

P: To me, that is very clear. My therapy helps many and harms nobody!

S: How do you know that it harms nobody?

… At this point, we have gone full circle and we can re-start this conversation from its beginning.

A recent article in LE PARISIEN entitled “L’homéopathie vétérinaire, c’est sans effet… mais pas sans risque” – Veterinary homeopathy is without effect … but not without risk, tells it like it is. Here are a few excerpts that I translated for you.

More than 77% of French people have tried homeopathy in their lifetime. But have you ever given it to your pet? Harmless in most cases, its use can be dangerous when it replaces a treatment whose effectiveness is scientifically proven … from a safety point of view, the tiny granules are indeed irreproachable: their use does not induce any drug interaction or undesirable side effects, nor does it run the risk of overdosing or addiction … homeopathic preparations owe their harmlessness to their lack of proper effects. “Neither in human medicine nor in veterinary medicine, at the current stage, clinical studies of all levels do not provide sufficient scientific evidence to support the therapeutic efficacy of homeopathic preparations”, stated the French Veterinary Academy in May 2021. These conclusions are in line with those of the French Academies of Medicine and Pharmacy, the British Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, and all the international scientific bodies that have given their opinion on the subject.

Therefore, when homeopathy delays diagnosis or is used in place of proven effective treatments, its use represents a “loss of opportunity” for your pet. The greatest danger of homeopathy is not that the remedies are ineffective, but that some homeopaths believe that their therapies can be used as a substitute for genuine medical treatment,” summarizes a petition to the UK veterinary regulatory body signed by more than 1,000 British veterinarians. At best, this claim is misleading and, at worst, it can lead to unnecessary suffering and death.”

But how can we explain the number of testimonies from pet owners who say that “it works”? “I am very satisfied with the Kalium Bichromicum granules for my cat with an eye ulcer, which is healing very well”… These improvements, real or supposed, can be explained by “contextual effects”, among which the famous placebo effect (which is not specific to humans), your subjective interpretation of his symptoms, or the natural history of the disease.

When these contextual effects are ignored or misunderstood, the spontaneous resolution or reduction of the disease can be wrongly attributed to homeopathy, and thus maintain the illusion of its effectiveness. This confusion is all the more likely because homeopathy owes much of its popularity to its use to treat “everyday ailments”: nausea, allergies, fatigue, bruises, nervousness, etc., which tend to get better on their own with time, or which have a fluctuating expression…

In April 2019, the association published an open letter addressed to the National Council of the Order of Veterinarians, calling on it to take a position on the compatibility of homeopathy with the “ethical and scientific requirements” of the profession. The organization, whose official function is to guarantee the quality of the service rendered to the public by the 20,000 veterinarians practicing in France, issued its conclusions last October. It invited veterinary training centers to remove homeopathy from their curricula, under penalty of having their accreditation withdrawn, and thus their ability to deliver training credits.

In my view, this is a remarkably good and informative text. How often do homeopathy fans claim IT WORKS FOR ANIMALS AND THUS CANNOT BE A PLACEBO! The truth is that, as we have so often discussed on this blog, homeopathy does not work beyond placebo for animals. This renders veterinary homeopathy:

- a waste of money,

- potentially dangerous,

- in the worst cases a form of animal abuse.

My advice is that, as soon as a vet recommends homeopathy, you look for the exit.

I know, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is not really a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) but it is used by many SCAM practitioners and pain patients. It is, therefore, worth knowing whether it works.

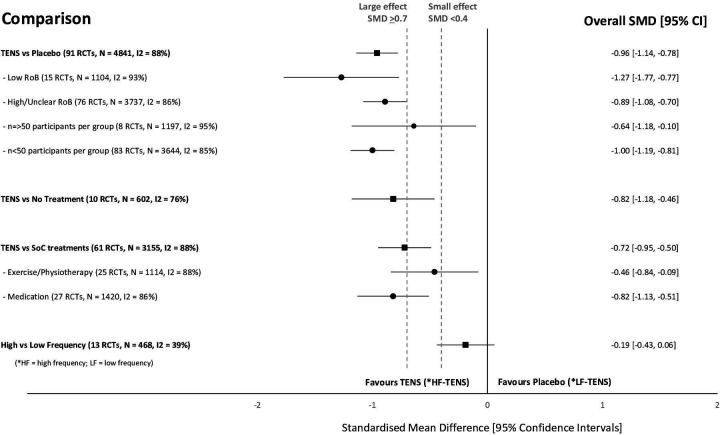

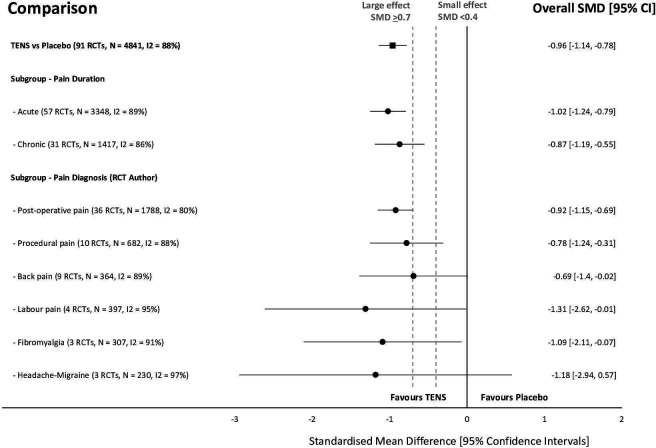

This systematic review investigated the efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for the relief of pain in adults. All randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were considered which compared strong non-painful TENS at or close to the site of pain versus placebo or other treatments in adults with pain, irrespective of diagnosis.

Reviewers independently screened, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias (RoB, Cochrane tool) and certainty of evidence (Grading and Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation). The outcome measures were the mean pain intensity and the proportions of participants achieving reductions of pain intensity (≥30% or >50%) during or immediately after TENS. Random effect models were used to calculate standardized mean differences (SMD) and risk ratios. Subgroup analyses were related to trial methodology and characteristics of pain.

The review included 381 RCTs (24 532 participants). Pain intensity was lower during or immediately after TENS compared with placebo (91 RCTs, 92 samples, n=4841, SMD=-0·96 (95% CI -1·14 to -0·78), moderate-certainty evidence). Methodological (eg, RoB, sample size) and pain characteristics (eg, acute vs chronic, diagnosis) did not modify the effect. Pain intensity was lower during or immediately after TENS compared with pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments used as part of standard of care (61 RCTs, 61 samples, n=3155, SMD = -0·72 (95% CI -0·95 to -0·50], low-certainty evidence). Levels of evidence were downgraded because of small-sized trials contributing to imprecision in magnitude estimates. Data were limited for other outcomes including adverse events which were poorly reported, generally mild, and not different from comparators.

The authors concluded that there was moderate-certainty evidence that pain intensity is lower during or immediately after TENS compared with placebo and without serious adverse events.

This is an impressive review, not least because of its rigorous methodology and the large number of included trials. Its results are clear and convincing. In the words of the authors: “TENS should be considered in a similar manner to rubbing, cooling or warming the skin to provide symptomatic relief of pain via neuromodulation. One advantage of TENS is that users can adjust electrical characteristics to produce a wide variety of TENS sensations such as pulsate and paraesthesiae to combat the dynamic nature of pain. Consequently, patients need to learn how to use a systematic process of trial and error to select electrode positions and electrical characteristics to optimise benefits and minimise problems on a moment to moment basis.”

Given the high prevalence of burdensome symptoms in palliative care (PC) and the increasing use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) therapies, research is needed to determine how often and what types of SCAM therapies providers recommend to manage symptoms in PC.

This survey documented recommendation rates of SCAM for target symptoms and assessed if, SCAM use varies by provider characteristics. The investigators conducted US nationwide surveys of MDs, DOs, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners working in PC.

Participants (N = 404) were mostly female (71.3%), MDs/DOs (74.9%), and cared for adults (90.4%). Providers recommended SCAM an average of 6.8 times per month (95% CI: 6.0-7.6) and used an average of 5.1 (95% CI: 4.9-5.3) out of 10 listed SCAM modalities. Respondents recommended mostly:

- mind-body medicines (e.g., meditation, biofeedback),

- massage,

- acupuncture/acupressure.

The most targeted symptoms included:

- pain,

- anxiety,

- mood disturbances,

- distress.

Recommendation frequencies for specific modality-for-symptom combinations ranged from little use (e.g. aromatherapy for constipation) to occasional use (e.g. mind-body interventions for psychiatric symptoms). Finally, recommendation rates increased as a function of pediatric practice, noninpatient practice setting, provider age, and proportion of effort spent delivering palliative care.

The authors concluded that to the best of our knowledge, this is the first national survey to characterize PC providers’ SCAM recommendation behaviors and assess specific therapies and common target symptoms. Providers recommended a broad range of SCAM but do so less frequently than patients report using SCAM. These findings should be of interest to any provider caring for patients with serious illness.

Initially, one might feel encouraged by these data. Mind-body therapies are indeed supported by reasonably sound evidence for the symptoms listed. The evidence is, however, not convincing for many other forms of SCAM, in particular massage or acupuncture/acupressure. So encouragement is quickly followed by disappointment.

Some people might say that in PC one must not insist on good evidence: if the patient wants it, why not? But the point is that there are several forms of SCAMs that are backed by good evidence for use in PC. So, why not follow the evidence and use those? It seems to me that it is not in the patients’ best interest to disregard the evidence in medicine – and this, of course, includes PC.

There are many patients in general practice with health complaints that cannot be medically explained. Some of these patients attribute their problems to dental amalgam.

This study examined the cost-effectiveness of the removal of amalgam fillings in patients with medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) attributed to amalgam compared to usual care, based on a prospective cohort study in Norway.

Costs were determined using a micro-costing approach at the individual level. Health outcomes were documented at baseline and approximately two years later for both the intervention and the usual care using EQ-5D-5L. Quality-adjusted life year (QALY) was used as the main outcome measure. A decision analytical model was developed to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of the intervention. Both probabilistic and one-way sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of uncertainty on costs and effectiveness.

In patients who attributed health complaints to dental amalgam and fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria, amalgam removal was associated with a modest increase in costs at the societal level as well as improved health outcomes. In the base-case analysis, the mean incremental cost per patient in the amalgam group was NOK 19 416 compared to the MUPS group, while the mean incremental QALY was 0.119 with a time horizon of two years. Thus, the incremental costs per QALY of the intervention were NOK 162 680, which is usually considered to be cost-effective in Norway. The estimated incremental cost per QALY decreased with increasing time horizons, and amalgam removal was found to be cost-saving over both 5 and 10 years.

The authors concluded that this study provides insight into the costs and health outcomes associated with the removal of amalgam restorations in patients who attribute health complaints to dental amalgam fillings, which are appropriate instruments to inform health care priorities.

The group sizes were 32 and 28 respectively. This study was thus almost laughably small and therefore cannot lead to firm conclusions of any type. In this contest, a recent systematic review might be relevant; it concluded as follows:

On the basis of the available RCTs, amalgam restorations, if compared with resin-based fillings, do not show an increased risk for systemic diseases. There is still insufficient evidence to exclude or demonstrate any direct influence on general health. The removal of old amalgam restorations and their substitution with more modern adhesive restorations should be performed only when clinically necessary and not just for material concerns. In order to better evaluate the safety of dental amalgam compared to other more modern restorative materials, further RCTs that consider important parameters such as long and uniform follow up periods, number of restorations per patient, and sample populations representative of chronic or degenerative diseases are needed.

Similarly, a review of the evidence might be informative:

Since more than 100 years amalgam is successfully used for the functional restoration of decayed teeth. During the early 1990s the use of amalgam has been discredited by a not very objective discussion about small amounts of quicksilver that can evaporate from the material. Recent studies and reviews, however, found little to no correlation between systemic or local diseases and amalgam restorations in man. Allergic reactions are extremely rare. Most quicksilver evaporates during placement and removal of amalgam restorations. Hence it is not recommended to make extensive rehabilitations with amalgam in pregnant or nursing women. To date, there is no dental material, which can fully substitute amalgam as a restorative material. According to present scientific evidence the use of amalgam is not a health hazard.

Furthermore, there is evidence that the removal of amalgam fillings is not such a good idea. One study, for instance, showed that the mercury released by the physical action of the drill, the replacement material and especially the final destination of the amalgam waste can increase contamination levels that can be a risk for human and environment health.

As dental amalgam removal does not seem risk-free, it is perhaps unwise to remove these fillings at all. Patients who are convinced that their amalgam fillings make them ill might simply benefit from assurance. After all, we also do not re-lay electric cables because some people feel they are the cause of their ill-health.

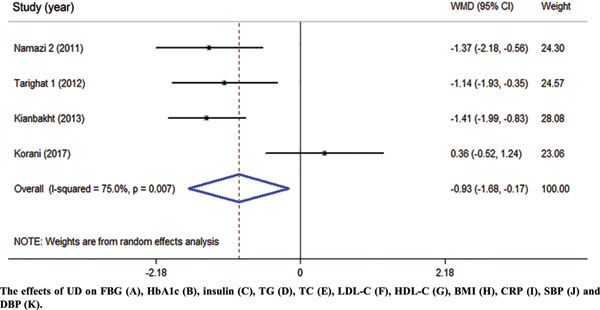

This systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials were performed to summarize the evidence of the effects of Urtica dioica (UD) consumption on metabolic profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Eligible studies were retrieved from searches of PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases until December 2019. Cochran (Q) and I-square statistics were used to examine heterogeneity across included clinical trials. Data were pooled using a fixed-effect or random-effects model and expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Among 1485 citations, thirteen clinical trials were found to be eligible for the current metaanalysis. UD consumption significantly decreased levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) (WMD = – 17.17 mg/dl, 95% CI: -26.60, -7.73, I2 = 93.2%), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (WMD = -0.93, 95% CI: – 1.66, -0.17, I2 = 75.0%), C-reactive protein (CRP) (WMD = -1.09 mg/dl, 95% CI: -1.64, -0.53, I2 = 0.0%), triglycerides (WMD = -26.94 mg/dl, 95 % CI = [-52.07, -1.82], P = 0.03, I2 = 90.0%), systolic blood pressure (SBP) (WMD = -5.03 mmHg, 95% CI = -8.15, -1.91, I2 = 0.0%) in comparison to the control groups. UD consumption did not significantly change serum levels of insulin (WMD = 1.07 μU/ml, 95% CI: -1.59, 3.73, I2 = 63.5%), total-cholesterol (WMD = -6.39 mg/dl, 95% CI: -13.84, 1.05, I2 = 0.0%), LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) (WMD = -1.30 mg/dl, 95% CI: -9.95, 7.35, I2 = 66.1%), HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) (WMD = 6.95 mg/dl, 95% CI: -0.14, 14.03, I2 = 95.4%), body max index (BMI) (WMD = -0.16 kg/m2, 95% CI: -1.77, 1.44, I2 = 0.0%), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (WMD = -1.35 mmHg, 95% CI: -2.86, 0.17, I2= 0.0%) among patients with T2DM.

The authors concluded that UD consumption may result in an improvement in levels of FBS, HbA1c, CRP, triglycerides, and SBP, but did not affect levels of insulin, total-, LDL-, and HDL-cholesterol, BMI, and DBP in patients with T2DM.

Several plants have been reported to affect the parameters of diabetes. Whenever I read such results, I cannot stop wondering whether this is a good or a bad thing. It seems to be positive at first glance, yet I can imagine at least two scenarios where such effects might be detrimental:

- A patient reads about the antidiabetic effects and decides to swap his medication for the herbal remedy which is far less effective. Consequently, the patient’s metabolic control is insufficient.

- A patient adds the herbal remedy to his therapy. Consequently, his blood sugar drops too far and he suffers a hypoglycemic episode.

My advice to diabetics is therefore this: if you want to try herbal antidiabetic treatments, please think twice. And if you persist, do it only under the close supervision of your doctor.

There is a lack of data describing the state of naturopathic or complementary veterinary medicine in Germany. This survey maps the currently used treatment modalities, indications, existing qualifications, and information pathways. It records the advantages and disadvantages of these medicines as experienced by veterinarians. Demographic influences are investigated to describe the distributional impacts of using veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine.

A standardized questionnaire was used for the cross-sectional survey. It was distributed throughout Germany in a written and digital format from September 2016 to January 2018. Because of the open nature of data collection, the return rate of questionnaires could not be calculated. To establish a feasible timeframe, active data collection stopped when the previously calculated limit of 1061 questionnaires was reached.

With the included incoming questionnaires of that day, a total of 1087 questionnaires were collected. Completely blank questionnaires and those where participants did not meet the inclusion criteria were not included, leaving 870 out of 1087 questionnaires to be evaluated. A literature review and the first test run of the questionnaire identified the following treatment modalities:

- homeopathy,

- phytotherapy,

- traditional Chinese medicine (TCM),

- biophysical treatments,

- manual treatments,

- Bach Flower Remedies,

- neural therapy,

- homotoxicology,

- organotherapy,

- hirudotherapy.

These were included in the questionnaire. Categorical items were processed using descriptive statistics in absolute and relative numbers based on the population of completed answers provided for each item. Multiple choices were possible.

Overall 85.4% of all the questionnaire participants used naturopathy and complementary medicine. The treatments most commonly used were:

- complex homoeopathy (70.4%, n = 478),

- phytotherapy (60.2%, n = 409),

- classic homoeopathy (44.3%, n = 301),

- biophysical treatments (40.1%, n = 272).

The most common indications were:

- orthopedic (n = 1798),

- geriatric (n = 1428),

- metabolic diseases (n = 1124).

Over the last five years, owner demand for naturopathy and complementary treatments was rated as growing by 57.9% of respondents (n = 457 of total 789). Veterinarians most commonly used scientific journals and publications as sources for information about naturopathic and complementary contents (60.8%, n = 479 of total 788). These were followed by advanced training acknowledged by the ATF (Academy for Veterinary Continuing Education, an organisation that certifies independent veterinary continuing education in Germany) (48.6%, n = 383). The current information about naturopathy and complementary medicine was rated as adequate or nearly adequate by many (39.5%, n = 308) of the respondents.

The most commonly named advantages in using veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine were:

- expansion of treatment modalities (73.5%, n = 566 of total 770),

- customer satisfaction (70.8%, n = 545),

- lower side effects (63.2%, n = 487).

The ambiguity and unclear evidence of the mode of action and effectiveness (62.1%, n = 483) and high expectations of owners (50.5%, n = 393) were the disadvantages mentioned most frequently. Classic homoeopathy, in particular, has been named in this context (78.4%, n = 333 of total 425). Age, gender, and type of employment showed a statistically significant impact on the use of naturopathy and complementary medicine by veterinarians (p < 0.001). The university of final graduation showed a weaker but still statistically significant impact (p = 0.027). Users of veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine tended to be older, female, self-employed and a higher percentage of them completed their studies at the University of Berlin. The working environment (rural or urban space) showed no statistical impact on the veterinary naturopathy or complementary medicine profession.

The authors concluded that this is the first study to provide German data on the actual use of naturopathy and complementary medicine in small animal science. Despite a potential bias due to voluntary participation, it shows a large number of applications for various indications. Homoeopathy was mentioned most frequently as the treatment option with the most potential disadvantages. However, it is also the most frequently used treatment option in this study. The presented study, despite its restrictions, supports the need for a discussion about evidence, official regulations, and the need for acknowledged qualifications because of the widespread application of veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine. More data regarding the effectiveness and the mode of action is needed to enable veterinarians to provide evidence-based advice to pet owners.

I can only hope that the findings are seriously biased and not a true reflection of the real situation. The methodology used for recruiting participants (it is fair to assume that those vets who had no interest in SCAM did not bother to respond) strongly indicates that this might be the case. If, however, the findings were true, one would have to conclude that, for German vets, evidence-based healthcare is still an alien concept. The evidence that the preferred SCAMs are effective for the listed conditions is very weak or even negative. If the findings were true, one would need to wonder how much of veterinary SCAM use amounts to animal abuse.

WARNING: SATIRE

This is going to be a very short post. Yet, I am sure you agree that my ‘golden rules’ encapsulate the collective wisdom of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM):

- Conventional treatments are dangerous

- Conventional doctors are ignorant

- Natural remedies are by definition good

- Ancient wisdom knows best

- SCAM tackles the roots of all health problems

- Experience trumps evidence

- People vote with their feet (SCAM’s popularity and patients’ satisfaction prove SCAM’s effectiveness)

- Science is barking up the wrong tree (what we need is a paradigm shift)

- Even Nobel laureates and other VIPs support SCAM

- Only SCAM practitioners care about the whole individual (mind, body, and soul)

- Science is not yet sufficiently advanced to understand how SCAM works (the mode of action has not been discovered)

- SCAM even works for animals (and thus cannot be a placebo)

- There is reliable evidence to support SCAM

- If a study of SCAM happens to yield a negative result, it is false-negative (e.g. because SCAM was not correctly applied)

- SCAM is patient-centered

- Conventional medicine is money-orientated

- The establishment is forced to suppress SCAM because otherwise, they would go out of business

- SCAM is reliable, constant, and unwavering (whereas conventional medicine changes its views all the time)

- SCAM does not need a monitoring system for adverse effects because it is inherently safe

- SCAM treatments are individualized (they treat the patient and not just a diagnostic label like conventional medicine)

- SCAM could save us all a lot of money

- There is no health problem that SCAM cannot cure

- Practitioners of conventional medicine have misunderstood the deeper reasons why people fall ill and should learn from SCAM

QED

I am sure that I have forgotten several important rules. If you can think of any, please post them in the comments section.