Chinese studies

I remember reading this paper entitled ‘Comparison of acupuncture and other drugs for chronic constipation: A network meta-analysis’ when it first came out. I considered discussing it on my blog, but then decided against it for a range of reasons which I shall explain below. The abstract of the original meta-analysis is copied below:

The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and side effects of acupuncture, sham acupuncture and drugs in the treatment of chronic constipation. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of acupuncture and drugs for chronic constipation were comprehensively retrieved from electronic databases (such as PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, CNKI, Wanfang Database, VIP Database and CBM) up to December 2017. Additional references were obtained from review articles. With quality evaluations and data extraction, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was performed using a random-effects model under a frequentist framework. A total of 40 studies (n = 11032) were included: 39 were high-quality studies and 1 was a low-quality study. NMA showed that (1) acupuncture improved the symptoms of chronic constipation more effectively than drugs; (2) the ranking of treatments in terms of efficacy in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome was acupuncture, polyethylene glycol, lactulose, linaclotide, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, prucalopride, sham acupuncture, tegaserod, and placebo; (3) the ranking of side effects were as follows: lactulose, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, polyethylene glycol, prucalopride, linaclotide, placebo and tegaserod; and (4) the most commonly used acupuncture point for chronic constipation was ST25. Acupuncture is more effective than drugs in improving chronic constipation and has the least side effects. In the future, large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to prove this. Sham acupuncture may have curative effects that are greater than the placebo effect. In the future, it is necessary to perform high-quality studies to support this finding. Polyethylene glycol also has acceptable curative effects with fewer side effects than other drugs.

END OF 1st QUOTE

This meta-analysis has now been retracted. Here is what the journal editors have to say about the retraction:

After publication of this article [1], concerns were raised about the scientific validity of the meta-analysis and whether it provided a rigorous and accurate assessment of published clinical studies on the efficacy of acupuncture or drug-based interventions for improving chronic constipation. The PLOS ONE Editors re-assessed the article in collaboration with a member of our Editorial Board and noted several concerns including the following:

- Acupuncture and related terms are not mentioned in the literature search terms, there are no listed inclusion or exclusion criteria related to acupuncture, and the outcome measures were not clearly defined in terms of reproducible clinical measures.

- The study included acupuncture and electroacupuncture studies, though this was not clearly discussed or reported in the Title, Methods, or Results.

- In the “Routine paired meta-analysis” section, both acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups were reported as showing improvement in symptoms compared with placebo. This finding and its implications for the conclusions of the article were not discussed clearly.

- Several included studies did not meet the reported inclusion criteria requiring that studies use adult participants and assess treatments of >2 weeks in duration.

- Data extraction errors were identified by comparing the dataset used in the meta-analysis (S1 Table) with details reported in the original research articles. Errors included aspects of the study design such as the experimental groups included in the study, the number of study arms in the trial, number of participants, and treatment duration. There are also several errors in the Reference list.

- With regard to side effects, 22 out of 40 studies were noted as having reported side effects. It was not made clear whether side effects were assessed as outcome measures for the other 18 studies, i.e. did the authors collect data clarifying that there were no side effects or was this outcome measure not assessed or reported in the original article. Without this clarification the conclusion comparing side effect frequencies is not well supported.

- The network geometry presented in Fig 5 is not correct and misrepresents some of the study designs, for example showing two-arm studies as three-arm studies.

- The overall results of the meta-analysis are strongly reliant on the evidence comparing acupuncture versus lactulose treatment. Several of the trials that assessed this comparison were poorly reported, and the meta-analysis dataset pertaining to these trials contained data extraction errors. Furthermore, potential bias in studies assessing lactulose efficacy in acupuncture trials versus lactulose efficacy in other trials was not sufficiently addressed.

While some of the above issues could be addressed with additional clarifications and corrections to the text, the concerns about study inclusion, the accuracy with which the primary studies’ research designs and data were represented in the meta-analysis, and the reporting quality of included studies directly impact the validity and accuracy of the dataset underlying the meta-analysis. As a consequence, we consider that the overall conclusions of the study are not reliable. In light of these issues, the PLOS ONE Editors retract the article. We apologize that these issues were not adequately addressed during pre-publication peer review.

LZ disagreed with the retraction. YM and XD did not respond.

END OF 2nd QUOTE

Let me start by explaining why I initially decided not to discuss this paper on my blog. Already the first sentence of the abstract put me off, and an entire chorus of alarm-bells started ringing once I read further.

- A meta-analysis is not a ‘study’ in my book, and I am somewhat weary of researchers who employ odd or unprecise language.

- We all know (and I have discussed it repeatedly) that studies of acupuncture frequently fail to report adverse effects (in doing this, their authors violate research ethics!). So, how can it be a credible aim of a meta-analysis to compare side-effects in the absence of adequate reporting?

- The methodology of a network meta-analysis is complex and I know not a lot about it.

- Several things seemed ‘too good to be true’, for instance, the funnel-plot and the overall finding that acupuncture is the best of all therapeutic options.

- Looking at the references, I quickly confirmed my suspicion that most of the primary studies were in Chinese.

In retrospect, I am glad I did not tackle the task of criticising this paper; I would probably have made not nearly such a good job of it as PLOS ONE eventually did. But it was only after someone raised concerns that the paper was re-reviewed and all the defects outlined above came to light.

While some of my concerns listed above may have been trivial, my last point is the one that troubles me a lot. As it also related to dozens of Cochrane reviews which currently come out of China, it is worth our attention, I think. The problem, as I see it, is as follows:

- Chinese (acupuncture, TCM and perhaps also other) trials are almost invariably reporting positive findings, as we have discussed ad nauseam on this blog.

- Data fabrication seems to be rife in China.

- This means that there is good reason to be suspicious of such trials.

- Many of the reviews that currently flood the literature are based predominantly on primary studies published in Chinese.

- Unless one is able to read Chinese, there is no way of evaluating these papers.

- Therefore reviewers of journal submissions tend to rely on what the Chinese review authors write about the primary studies.

- As data fabrication seems to be rife in China, this trust might often not be justified.

- At the same time, Chinese researchers are VERY keen to publish in top Western journals (this is considered a great boost to their career).

- The consequence of all this is that reviews of this nature might be misleading, even if they are published in top journals.

I have been struggling with this problem for many years and have tried my best to alert people to it. However, it does not seem that my efforts had even the slightest success. The stream of such reviews has only increased and is now a true worry (at least for me). My suspicion – and I stress that it is merely that – is that, if one would rigorously re-evaluate these reviews, their majority would need to be retracted just as the above paper. That would mean that hundreds of papers would disappear because they are misleading, a thought that should give everyone interested in reliable evidence sleepless nights!

So, what can be done?

Personally, I now distrust all of these papers, but I admit, that is not a good, constructive solution. It would be better if Journal editors (including, of course, those at the Cochrane Collaboration) would allocate such submissions to reviewers who:

- are demonstrably able to conduct a CRITICAL analysis of the paper in question,

- can read Chinese,

- have no conflicts of interest.

In the case of an acupuncture review, this would narrow it down to perhaps just a handful of experts worldwide. This probably means that my suggestion is simply not feasible.

But what other choice do we have?

One could oblige the authors of all submissions to include full and authorised English translations of non-English articles. I think this might work, but it is, of course, tedious and expensive. In view of the size of the problem (I estimate that there must be around 1 000 reviews out there to which the problem applies), I do not see a better solution.

(I would truly be thankful, if someone had a better one and would tell us)

Psoriasis is one of those conditions that is

- chronic,

- not curable,

- irritating to the point where it reduces quality of life.

In other words, it is a disease for which virtually all alternative treatments on the planet are claimed to be effective. But which therapies do demonstrably alleviate the symptoms?

This review (published in JAMA Dermatology) compiled the evidence on the efficacy of the most studied complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities for treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis and discusses those therapies with the most robust available evidence.

PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov searches (1950-2017) were used to identify all documented CAM psoriasis interventions in the literature. The criteria were further refined to focus on those treatments identified in the first step that had the highest level of evidence for plaque psoriasis with more than one randomized clinical trial (RCT) supporting their use. This excluded therapies lacking RCT data or showing consistent inefficacy.

A total of 457 articles were found, of which 107 articles were retrieved for closer examination. Of those articles, 54 were excluded because the CAM therapy did not have more than 1 RCT on the subject or showed consistent lack of efficacy. An additional 7 articles were found using references of the included studies, resulting in a total of 44 RCTs (17 double-blind, 13 single-blind, and 14 nonblind), 10 uncontrolled trials, 2 open-label nonrandomized controlled trials, 1 prospective controlled trial, and 3 meta-analyses.

Compared with placebo, application of topical indigo naturalis, studied in 5 RCTs with 215 participants, showed significant improvements in the treatment of psoriasis. Treatment with curcumin, examined in 3 RCTs (with a total of 118 participants), 1 nonrandomized controlled study, and 1 uncontrolled study, conferred statistically and clinically significant improvements in psoriasis plaques. Fish oil treatment was evaluated in 20 studies (12 RCTs, 1 open-label nonrandomized controlled trial, and 7 uncontrolled studies); most of the RCTs showed no significant improvement in psoriasis, whereas most of the uncontrolled studies showed benefit when fish oil was used daily. Meditation and guided imagery therapies were studied in 3 single-blind RCTs (with a total of 112 patients) and showed modest efficacy in treatment of psoriasis. One meta-analysis of 13 RCTs examined the association of acupuncture with improvement in psoriasis and showed significant improvement with acupuncture compared with placebo.

The authors concluded that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis are indigo naturalis, curcumin, dietary modification, fish oil, meditation, and acupuncture. This review will aid practitioners in advising patients seeking unconventional approaches for treatment of psoriasis.

I am sorry to say so, but this review smells fishy! And not just because of the fish oil. But the fish oil data are a good case in point: the authors found 12 RCTs of fish oil. These details are provided by the review authors in relation to oral fish oil trials: Two double-blind RCTs (one of which evaluated EPA, 1.8g, and DHA, 1.2g, consumed daily for 12 weeks, and the other evaluated EPA, 3.6g, and DHA, 2.4g, consumed daily for 15 weeks) found evidence supporting the use of oral fish oil. One open-label RCT and 1 open-label non-randomized controlled trial also showed statistically significant benefit. Seven other RCTs found lack of efficacy for daily EPA (216mgto5.4g)or DHA (132mgto3.6g) treatment. The remainder of the data supporting efficacy of oral fish oil treatment were based on uncontrolled trials, of which 6 of the 7 studies found significant benefit of oral fish oil. This seems to support their conclusion. However, the authors also state that fish oil was not shown to be effective at several examined doses and duration. Confused? Yes, me too!

Even more confusing is their failure to mention a single trial of Mahonia aquifolium. A 2013 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Dermatology included 5 RCTs of Mahonia aquifolium which, according to these authors, provided ‘limited support’ for its effectiveness. How could they miss that?

More importantly, how could the reviewers miss to conduct a proper evaluation of the quality of the studies they included in their review (even in their abstract, they twice speak of ‘robust evidence’ – but how can they without assessing its robustness? [quantity is not remotely the same as quality!!!]). Without a transparent evaluation of the rigour of the primary studies, any review is nearly worthless.

Take the 12 acupuncture trials, for instance, which the review authors included based not on an assessment of the studies but on a dodgy review published in a dodgy journal. Had they critically assessed the quality of the primary studies, they could have not stated that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis …[include]… acupuncture. Instead they would have had to admit that these studies are too dubious for any firm conclusion. Had they even bothered to read them, they would have found that many are in Chinese (which would have meant they had to be excluded in their review [as many pseudo-systematic reviewers, the authors only considered English papers]).

There might be a lesson in all this – well, actually I can think of at least two:

- Systematic reviews might well be the ‘Rolls Royce’ of clinical evidence. But even a Rolls Royce needs to be assembled correctly, otherwise it is just a heap of useless material.

- Even top journals do occasionally publish poor-quality and thus misleading reviews.

If you thought that Chinese herbal medicine is just for oral use, you were wrong. This article explains it all in some detail: Injections of traditional Chinese herbal medicines are also referred to as TCM injections. This approach has evolved during the last 70 years as a treatment modality that, according to the authors, parallels injections of pharmaceutical products.

The researchers from China try to provide a descriptive analysis of various aspects of TCM injections. They used the the following data sources: (1) information retrieved from website of drug registration system of China, and (2) regulatory documents, annual reports and ADR Information Bulletins issued by drug regulatory authority.

As of December 31, 2017, 134 generic names for TCM injections from 224 manufacturers were approved for sale. Only 5 of the 134 TCM injections are documented in the present version of Ch.P (2015). Most TCM injections are documented in drug standards other than Ch.P. The formulation, ingredients and routes of administration of TCM injections are more complex than conventional chemical injections. Ten TCM injections are covered by national lists of essential medicine and 58 are covered by China’s basic insurance program of 2017. Adverse drug reactions (ADR) reports related to TCM injections account for over 50% of all ADR reports related to TCMs, and the percentages have been rising annually.

The authors concluded that making traditional medicine injectable might be a promising way to develop traditional medicines. However, many practical challenges need to be overcome by further development before a brighter future for injectable traditional medicines can reasonably be expected.

I have to admit that TCM injections frighten the hell out of me. I feel that before we inject any type of substance into patients, we ought to know as a bare minimum:

- for what conditions, if any, they have been proven to be efficacious,

- what adverse effects each active ingredient can cause,

- with what other drugs they might interact,

- how reliable the quality control for these injections is.

I somehow doubt that these issues have been fully addressed in China. Therefore, I can only hope the Chinese manufacturers are not planning to export their dubious TCM injections.

I have often cautioned my readers about the ‘evidence’ supporting acupuncture (and other alternative therapies). Rightly so, I think. Here is yet another warning.

This systematic review assessed the clinical effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD). Nine trials involving 653 women were selected. A meta-analysis demonstrated that the acupuncture group had a significantly greater overall effective rate compared with the control group. Moreover, acupuncture significantly increased oestradiol levels compared with the control group. Regarding the HAMD and EPDS scores, no difference was found between the two groups. The Chinese authors concluded that acupuncture appears to be effective for postpartum depression with respect to certain outcomes. However, the evidence thus far is inconclusive. Further high-quality RCTs following standardised guidelines with a low risk of bias are needed to confirm the effectiveness of acupuncture for postpartum depression.

What a conclusion!

What a review!

What a journal!

What evidence!

Let’s start with the conclusion: if the authors feel that the evidence is ‘inconclusive’, why do they state that ‘acupuncture appears to be effective for postpartum depression‘. To me this does simply not make sense!

Such oddities are abundant in the review. The abstract does not mention the fact that all trials were from China (published in Chinese which means that people who cannot read Chinese are unable to check any of the reported findings), and their majority was of very poor quality – two good reasons to discard the lot without further ado and conclude that there is no reliable evidence at all.

The authors also tell us very little about the treatments used in the control groups. In the paper, they state that “the control group needed to have received a placebo or any type of herb, drug and psychological intervention”. But was acupuncture better than all or any of these treatments? I could not find sufficient data in the paper to answer this question.

Moreover, only three trials seem to have bothered to mention adverse effects. Thus the majority of the studies were in breach of research ethics. No mention is made of this in the discussion.

In the paper, the authors re-state that “this meta-analysis showed that the acupuncture group had a significantly greater overall effective rate compared with the control group. Moreover, acupuncture significantly increased oestradiol levels compared with the control group.” This is, I think, highly misleading (see above).

Finally, let’s have a quick look at the journal ‘Acupuncture in Medicine’ (AiM). Even though it is published by the BMJ group (the reason for this phenomenon can be found here: “AiM is owned by the British Medical Acupuncture Society and published by BMJ”; this means that all BMAS-members automatically receive the journal which thus is a resounding commercial success), it is little more than a cult-newsletter. The editorial board is full of acupuncture enthusiasts, and the journal hardly ever publishes anything that is remotely critical of the wonderous myths of acupuncture.

My conclusion considering all this is as follows: we ought to be very careful before accepting any ‘evidence’ that is currently being published about the benefits of acupuncture, even if it superficially looks ok. More often than not, it turns out to be profoundly misleading, utterly useless and potentially harmful pseudo-evidence.

Reference

Acupunct Med. 2018 Jun 15. pii: acupmed-2017-011530. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2017-011530. [Epub ahead of print]

Effectiveness of acupuncture in postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Li S, Zhong W, Peng W, Jiang G.

Most people probably think of acupuncture as being used mainly as a therapy for pain control. But acupuncture is currently being promoted (and has traditionally been used) for all sorts of conditions. One of them is stroke. It is said to speed up recovery and even improve survival rates after such an event. There are plenty of studies on this subject, but their results are far from uniform. What is needed in this situation, is a rigorous summary of the evidence.

The authors of this Cochrane review wanted to assess whether acupuncture could reduce the proportion of people suffering death or dependency after acute ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke. They included all randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of acupuncture started within 30 days after stroke onset. Acupuncture had to be compared with placebo or sham acupuncture or open control (no placebo) in people with acute ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, or both. Comparisons were made versus (1) all controls (open control or sham acupuncture), and (2) sham acupuncture controls.

The investigators included 33 RCTs with 3946 participants. Outcome data were available for up to 22 trials (2865 participants) that compared acupuncture with any control (open control or sham acupuncture) but for only 6 trials (668 participants) comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture.

When compared with any control (11 trials with 1582 participants), findings of lower odds of death or dependency at the end of follow-up and over the long term (≥ three months) in the acupuncture group were uncertain and were not confirmed by trials comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture. In trials comparing acupuncture with any control, findings that acupuncture was associated with increases in the global neurological deficit score and in the motor function score were uncertain. These findings were not confirmed in trials comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture.Trials comparing acupuncture with any control showed little or no difference in death or institutional care or death at the end of follow-up.The incidence of adverse events (eg, pain, dizziness, faint) in the acupuncture arms of open and sham control trials was 6.2% (64/1037 participants), and 1.4% of these patients (14/1037 participants) discontinued acupuncture. When acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture, findings for adverse events were uncertain.

The authors concluded that this updated review indicates that apparently improved outcomes with acupuncture in acute stroke are confounded by the risk of bias related to use of open controls. Adverse events related to acupuncture were reported to be minor and usually did not result in stopping treatment. Future studies are needed to confirm or refute any effects of acupuncture in acute stroke. Trials should clearly report the method of randomization, concealment of allocation, and whether blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors was achieved, while paying close attention to the effects of acupuncture on long-term functional outcomes.

This Cochrane review seems to be thorough, but it is badly written (Cochrane reviewers: please don’t let this become the norm!). It contains some interesting facts. The majority of the studies came from China. This review confirmed the often very poor methodological quality of acupuncture trials which I have frequently mentioned before.

In particular, the RCTs originating from China were amongst those that most overtly lacked rigor, also a fact that has been discussed regularly on this blog.

For me, by far the most important finding of this review is that studies which at least partly control for placebo effects fail to show positive results. Depending on where you stand in the never-ending debate about acupuncture, this could lead to two dramatically different conclusions:

- If you are a believer in or earn your living from acupuncture, you might say that these results suggest that the trials were in some way insufficient and therefore they produced false-negative results.

- If you are a more reasonable observer, you might feel that these results show that acupuncture (for acute stroke) is a placebo therapy.

Regardless to which camp you belong, one thing seems to be certain: acupuncture for stroke (and other indications) is not supported by sound evidence. And that means, I think, that it is not responsible to use it in routine care.

The only time we discussed gua sha, it led to one of the most prolonged discussions we ever had on this blog (536 comments so far). It seems to be a topic that excites many. But what precisely is it?

The only time we discussed gua sha, it led to one of the most prolonged discussions we ever had on this blog (536 comments so far). It seems to be a topic that excites many. But what precisely is it?

Gua sha, sometimes referred to as “scraping”, “spooning” or “coining”, is a traditional Chinese treatment that has spread to several other Asian countries. It has long been popular in Vietnam and is now also becoming well-known in the West. The treatment consists of scraping the skin with a smooth edge placed against the pre-oiled skin surface, pressed down firmly, and then moved downwards along muscles or meridians. According to its proponents, gua sha stimulates the flow of the vital energy ‘chi’ and releases unhealthy bodily matter from blood stasis within sore, tired, stiff or injured muscle areas.

The technique is practised by TCM practitioners, acupuncturists, massage therapists, physical therapists, physicians and nurses. Practitioners claim that it stimulates blood flow to the treated areas, thus promoting cell metabolism, regeneration and healing. They also assume that it has anti-inflammatory effects and stimulates the immune system.

These effects are said to last for days or weeks after a single treatment. The treatment causes microvascular injuries which are visible as subcutaneous bleeding and redness. Gua sha practitioners make far-reaching therapeutic claims, including that the therapy alleviates pain, prevents infections, treats asthma, detoxifies the body, cures liver problems, reduces stress, and contributes to overall health.

Gua sha is mildly painful, almost invariably leads to unsightly blemishes on the skin which occasionally can become infected and might even be mistaken for physical abuse.

There is little research of gua sha, and the few trials that exist tend to be published in Chinese. But recently, a new paper has emerged that is written in English. The goal of this systematic review was to evaluate the available evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of gua sha for the treatment of patients with perimenopausal syndrome.

A total of 6 RCTs met the inclusion criteria. Most were of low methodological quality. When compared with Western medicine therapy alone, meta-analysis of 5 RCTs indicated favorable statistically significant effects of gua sha plus Western medicine. Moreover, study participants who received Gua Sha therapy plus Western medicine therapy showed significantly greater improvements in serum levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) compared to participants in the Western medicine therapy group.

The authors concluded that preliminary evidence supported the hypothesis that Gua Sha therapy effectively improved the treatment efficacy in patients with perimenopausal syndrome. Additional studies will be required to elucidate optimal frequency and dosage of Gua Sha.

This sounds as though gua sha is a reasonable therapy.

Yet, I think this notion is worth being critically analysed. Here are some caveats that spring into my mind:

- Gua sha lacks biological plausibility.

- The reviewed trials are too flawed to allow any firm conclusions.

- As most are published in Chinese, non-Chinese speakers have no possibility to evaluate them.

- The studies originate from China where close to 100% of TCM trials report positive results.

- In my view, this means they are less than trustworthy.

- The authors of the above-cited review are all from China and might not be willing, able or allowed to publish a critical paper on this subject.

- The review was published in Complement Ther Clin Pract., a journal not known for its high scientific standards or critical stance towards TCM.

So, is gua sha a reasonable therapy?

I let you make this judgement.

On this blog, we have seen more than enough evidence of how some proponents of alternative medicine can react when they feel cornered by critics. They often direct vitriol in their direction. Ad hominem attacks are far from being rarities. A more forceful option is to sue them for libel. In my own case, Prince Charles went one decisive step further and made sure that my entire department was closed down. In China, they have recently and dramatically gone even further.

This article in Nature tells the full story:

A Chinese doctor who was arrested after he criticized a best-selling traditional Chinese remedy has been released, after more than three months in detention. Tan Qindong had been held at the Liangcheng county detention centre since January, when police said a post Tan had made on social media damaged the reputation of the traditional medicine and the company that makes it.

On 17 April, a provincial court found the police evidence for the case insufficient. Tan, a former anaesthesiologist who has founded several biomedical companies, was released on bail on that day. Tan, who lives in Guangzhou in southern China, is now awaiting trial. Lawyers familiar with Chinese criminal law told Nature that police have a year to collect more evidence or the case will be dismissed. They say the trial is unlikely to go ahead…

The episode highlights the sensitivities over traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) in China. Although most of these therapies have not been tested for efficacy in randomized clinical trials — and serious side effects have been reported in some1 — TCM has support from the highest levels of government. Criticism of remedies is often blocked on the Internet in China. Some lawyers and physicians worry that Tan’s arrest will make people even more hesitant to criticize traditional therapies…

Tan’s post about a medicine called Hongmao liquor was published on the Chinese social-media app Meipian on 19 December…Three days later, the liquor’s maker, Hongmao Pharmaceuticals in Liangcheng county of Inner Mongolia autonomous region, told local police that Tan had defamed the company. Liangcheng police hired an accountant who estimated that the damage to the company’s reputation was 1.4 million Chinese yuan (US$220,000), according to official state media, the Beijing Youth Daily. In January, Liangcheng police travelled to Guangzhou to arrest Tan and escort him back to Liangcheng, according to a police statement.

Sales of Hongmao liquor reached 1.63 billion yuan in 2016, making it the second best-selling TCM in China that year. It was approved to be sold by licensed TCM shops and physicians in 1992 and approved for sale over the counter in 2003. Hongmao Pharmaceuticals says that the liquor can treat dozens of different disorders, including problems with the spleen, stomach and kidney, as well as backaches…

Hongmao Pharmaceuticals did not respond to Nature’s request for an interview. However, Wang Shengwang, general manager of the production center of Hongmao Liquor, and Han Jun, assistant to the general manager, gave an interview to The Paper on 16 April. The pair said the company did not need not publicize clinical trial data because Hongmao liquor is a “protected TCM composition”. Wang denied allegations in Chinese media that the company pressured the police to pursue Tan or that it dispatched staff to accompany the police…

Xia is worried that the case could further silence public criticism of TCMs, environmental degredation, and other fields where comment from experts is crucial. The Tan arrest “could cause fear among scientists” and dissuade them from posting scientific comments, he says.

END OF QUOTE

On this blog, we have repeatedly discussed concerns over the validity of TCM data/material that comes out of China (see for instance here, here and here). This chilling case, I am afraid, is not prone to increase our confidence.

Difficulties breastfeeding?

Some say that Chinese herbal medicine offers a solution.

This Chinese multi-centre RCT included 588 mothers considering breastfeeding. The intervention group received the Chinese herbal mixture Zengru Gao, while the control group received no therapy. The primary outcomes were the percentages of fully and partially breastfeeding mothers, and a secondary outcome was baby’s daily formula intake.

At day 3 and 7 after delivery, significant differences were found in favour of Zengru Gao group on the percentage of full/ partial breastfeeding. At day 7, the percentage of full/ partial breastfeeding of the active group increased to 71.48%/20.70% versus 58.67%/30.26% in the control group, the differences remained significant. No statistically significant differences were detected on primary measures at day. While intake of formula differed between groups at day 1 and 3, this difference did not achieve statistical significance, but this difference was apparent by day 7.

The authors concluded that the Chinese Herbal medicine Zengru Gao enhanced breastfeeding success during one week postpartum. The approach is acceptable to participants and merits further evaluation.

To the naïve observer, this study might look rigorous, but it is a seriously flawed RCT. Here are just some of its most obvious limitations:

- All we get in the methods section is this explanation: Participants were randomly allocated to the blank control group or the intervention group: Zengru Gao, orally, 30 g a time and 3 times a day. This seems to indicate that the control group got no treatment at all which means there was no blinding nor placebo control. The authors even comment on this point in the discussion section of their paper stating that because we included new mothers who received no treatment as a control group, we were able to prove that the improvement in breastfeeding was not due to the placebo effect. However, this is a totally nonsensical argument.

- The experimental treatment is not reproducible. The authors state: Zengru Gao, a Chinese herbal formula, which is composed of 8 herbs: Semen Vaccariae, Medulla Tetrapanacis, Radix Rehmanniae Praeparata, Radix Angelicae Sinensis, Radix Paeoniae Alba,Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Herba Leonuri, Radix Trichosanthis. This is not enough information to replicate the study outside China where the mixture is not commercially available.

- The primary outcome was the percentage of fully, and partially breastfeeding mothers. Breastfeeding was defined as mother’s milk given by direct breast feeding. Full breastfeeding meant that no other types of milk or solids were given. Partially breastfeeding meant that sustained latch with deep rhythmic sucking through the length of the feed, with some pause, on either/ or both breasts. We are not being told how the endpoint was quantified. Presumably women kept diaries. We cannot guess how accurate this process was.

- As far as I can see, there was no correction for multiple testing for statistical significance. This means that some or all of the significant results might be false-positive.

- There is insufficient data to show that the herbal mixture is safe for the mothers and the babies. At the very minimum, the researchers should have measured essential safety parameters. This omission is a gross violation of research ethics.

- Towards the end of the paper, we find the following statement: The authors would like to thank the Research and Development Department of Zhangzhou Pien Tze Huang Pharmaceutical co., Ltd. … The authors declare that they have no competing interests. And the 1st and 3rd authors are “affiliated with” Guangzhou Hipower Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China, i. e. work for the manufacturer of the mixture. This does clearly not make any sense whatsoever.

I have seen too many flawed studies of alternative medicine to be shocked or even surprised by this level of incompetence and nonsense. Yet, I still find it lamentable. But, in my view, the worst is that supposedly peer-reviewed journals such as ‘BMC Complement Altern Med’ publish such overt rubbish.

It would be easy to shrug one’s shoulder and bin the paper. But the effect of such fatally flawed research is too serious for that. In our recent book MORE HARM THAN GOOD? THE MORAL MAZE OF COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE, we discuss that such flawed science amounts to a violation of medical ethics: CAM journals allocate peer review tasks to a narrow range of CAM enthusiasts who often have been chosen by the authors of the article in question. The raison d’être of CAM journals and CAM researchers is inextricably tied to a belief in CAM, resulting in a self-referential situation which is permissive to the acceptance of weak or flawed reports of clinical effectiveness… Defective research—whether at the design, execution, analysis, or reporting stage—corrupts the repository of reliable medical knowledge. Ultimately, this leads to suboptimal and erroneous treatment decisions…

Can conventional therapy (CT) be combined with herbal therapy (CT + H) in the management of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to the benefit of patients? This was the question investigated by Chinese researchers in a recent retrospective cohort study funded by grants from China Ministry of Education, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission, and Beijing Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning.

In total, 344 outpatients diagnosed as probable dementia due to AD were collected, who had received either CT + H or CT alone. The GRAPE formula was prescribed for AD patients after every visit according to TCM theory. It consisted mainly (what does ‘mainly’ mean as a description of a trial intervention?) of Ren shen (Panax ginseng, 10 g/d), Di huang (Rehmannia glutinosa, 30 g/d), Cang pu (Acorus tatarinowii, 10 g/d), Yuan zhi (Polygala tenuifolia, 10 g/d), Yin yanghuo (Epimedium brevicornu, 10 g/d), Shan zhuyu (Cornus officinalis, 10 g/d), Rou congrong (Cistanche deserticola, 10 g/d), Yu jin (Curcuma aromatica, 10 g/d), Dan shen (Salvia miltiorrhiza, 10 g/d), Dang gui (Angelica sinensis, 10 g/d), Tian ma (Gastrodia elata, 10 g/d), and Huang lian (Coptis chinensis, 10 g/d), supplied by Beijing Tcmages Pharmaceutical Co., LTD. Daily dose was taken twice and dissolved in 150 ml hot water each time. Cognitive function was quantified by the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) every 3 months for 24 months.

The results show that most of the patients were initially diagnosed with mild (MMSE = 21-26, n = 177) and moderate (MMSE = 10-20, n = 137) dementia. At 18 months, CT+ H patients scored on average 1.76 (P = 0.002) better than CT patients, and at 24 months, patients scored on average 2.52 (P < 0.001) better. At 24 months, the patients with improved cognitive function (△MMSE ≥ 0) in CT + H was more than CT alone (33.33% vs 7.69%, P = 0.020). Interestingly, patients with mild AD received the most robust benefit from CT + H therapy. The deterioration of the cognitive function was largely prevented at 24 months (ΔMMSE = -0.06), a significant improvement from CT alone (ΔMMSE = -2.66, P = 0.005).

The authors concluded that, compared to CT alone, CT + H significantly benefited AD patients. A symptomatic effect of CT + H was more pronounced with time. Cognitive decline was substantially decelerated in patients with moderate severity, while the cognitive function was largely stabilized in patients with mild severity over two years. These results imply that Chinese herbal medicines may provide an alternative and additive treatment for AD.

Conclusions like these render me speechless – well, almost speechless. This was nothing more than a retrospective chart analysis. It is not possible to draw causal conclusions from such data.

Why?

Because of a whole host of reasons. Most crucially, the CT+H patients were almost certainly a different and therefore non-comparable population to the CT patients. This flaw is so elementary that I need to ask, who are the reviewers letting such utter nonsense pass, and which journal would publish such rubbish? In fact, I can be used for teaching students why randomisation is essential, if we aim to find out about cause and effect.

Ahhh, it’s the BMC Complement Altern Med! I think the funders, editors, reviewers, and authors of this paper should all go and hide in shame.

A new acupuncture study puzzles me a great deal. It is a “randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial” evaluating acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue (CRF) in lung cancer patients. Twenty-eight patients presenting with CRF were randomly assigned to active acupuncture or placebo acupuncture groups to receive acupoint stimulation at LI-4, Ren-6, St-36, KI-3, and Sp-6 twice weekly for 4 weeks, followed by 2 weeks of follow-up. The primary outcome measure was the change in intensity of CFR based on the Chinese version of the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI-C). The secondary endpoint was the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung Cancer Subscale (FACT-LCS). Adverse events were monitored throughout the trial.

A significant reduction in the BFI-C score was observed at 2 weeks in the 14 participants who received active acupuncture compared with those receiving the placebo. At week 6, symptoms further improved. There were no significant differences in the incidence of adverse events of the two group.

The authors, researchers from Shanghai, concluded that fatigue is a common symptom experienced by lung cancer patients. Acupuncture may be a safe and feasible optional method for adjunctive treatment in cancer palliative care, and appropriately powered trials are warranted to evaluate the effects of acupuncture.

And why would this be puzzling?

There are several minor oddities here, I think:

- The first sentence of the conclusion is not based on the data presented.

- The notion that acupuncture ‘may be safe’ is not warranted from the study of 14 patients.

- The authors call their trial a ‘pilot study’ in the abstract, but refer to it as an ‘efficacy study’ in the text of the article.

But let’s not be nit-picking; these are minor concerns compared to the fact that, even in the title of the paper, the authors call their trial ‘double-blind’.

How can an acupuncture-trial be double-blind?

The authors used the non-penetrating Park needle, developed by my team, as a placebo. We have shown that, indeed, patients can be properly blinded, i. e. they don’t know whether they receive real or placebo acupuncture. But the acupuncturist clearly cannot be blinded. So, the study is clearly NOT double-blind!

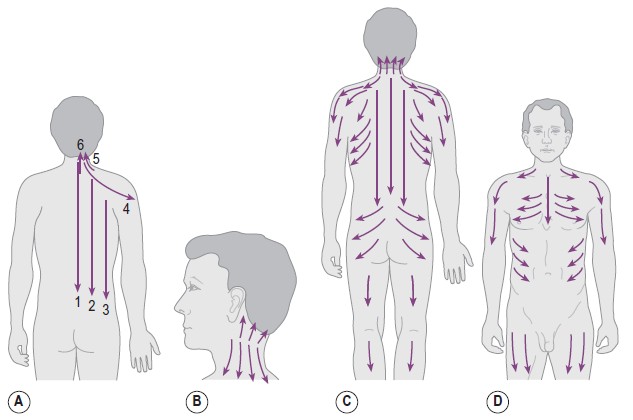

As though this were not puzzling enough, there is something even more odd here. In the methods section of the paper the authors explain that they used our placebo-needle (without referencing our research on the needle development) which is depicted below.

Then they state that “the device is placed on the skin. The needle is then gently tapped to insert approximately 5 mm, and the guide tube is then removed to allow sufficient exposure of the handle for needle manipulation.” No further explanations are offered thereafter as to the procedure used.

Removing the guide tube while using our device is only possible in the real acupuncture arm. In the placebo arm, the needle telescopes thus giving the impression it has penetrated the skin; but in fact it does not penetrate at all. If one would remove the guide tube, the non-penetrating placebo needle would simply fall off. This means that, by removing the guide tube for ease of manipulation, the researchers disclose to their patients that they are in the real acupuncture group. And this, in turn, means that the trial was not even single-blind. Patients would have seen whether they received real or placebo acupuncture.

It follows that all the outcomes noted in this trial are most likely due to patient and therapist expectations, i. e. they were caused by a placebo effect.

Now that we have solved this question, here is the next one: IS THIS A MISUNDERSTANDING, CLUMSINESS, STUPIDITY, SCIENTIFIC MISCONDUCT OR FRAUD?