causation

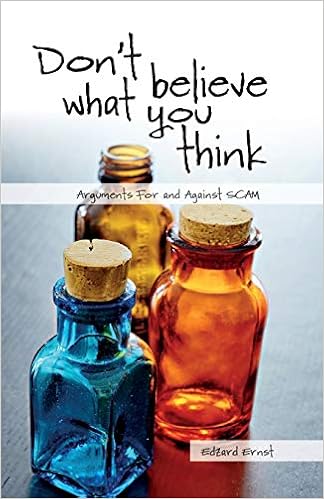

Today is the official publication date of my new book ‘DON’T BELIEVE WHAT YOU THINK‘. It is essentially a crash course in critical thinking. To give you a flavour, here is an excerpt from its preface:

… So-called alternative medicine (SCAM) is a complex and controversial subject. Many people pretend to be experts in SCAM, but few know even the basic facts about it. Many consumers talk about SCAM, but few can be bothered to look behind the smokescreen of misleading claims. Many feel emotionally attached to SCAM, but few manage to think rationally about it. Many religiously believe in SCAM, but few show concern about the evidence. Many are desperate for help, but few seem to mind getting ripped off…

Enthusiasts of SCAM tend to hope for less side-effects, symptom relief, a cure of their condition, improvements in quality of life, and protection from illness. Such high expectations are usually based on misinformation, often even on outright lies. The disappointing truth is that not many SCAMs are truly effective in treating or preventing disease, and that none is totally harmless. In fact, the dangers of SCAM are multi-fold and potentially serious:

- harm due to adverse effects such as toxicity of an herbal remedy, stroke after chiropractic manipulation, pneumothorax after acupuncture (see chapter 3.2);

- harm caused by bogus diagnostic techniques (see chapter 4.4);

- harm of using materials from endangered species (see chapter 3.15);

- harm through incompetent advice by SCAM providers (see chapter 4.5);

- harm due to using SCAM instead of an effective therapy for serious conditions (see chapter 4.5);

- harm due to the high costs of SCAM (see chapter 3.8);

- harm due to SCAM undermining evidence-based medicine (see chapter 5.4);

- harm caused by inhibiting medical progress and research (see chapter 5.1).

In this book, I address these issues in detail and explain how consumers get manipulated into believing things that are evidently wrong. Using plenty of real-life examples, I outline how the constant flow of misinformation, coupled with motivated ignorance, motivated reasoning, and cognitive bias can produce a form of wishful thinking that is detached from reality. In the interest of my readers’ health, I aim to correct some of these false beliefs and fallacious thought processes.

My book consists of 35 concise essays each of which addresses one commonly held belief about SCAM. The essays can be read as stand-alone articles; occasionally, this necessitates a degree of repetition which, however, is minimal. The text avoids technical jargon and is therefore easy to follow. For those who want to dig deeper into the scientific evidence, links are provided to numerous papers that might prove to be helpful. A glossary is added at the end to explain some terms that might be unfamiliar.

This book is meant to stimulate critical thinking not just about SCAM, but also in a more general way. Science deniers employ similar techniques no matter whether they focus on health, climate change, evolution or other subjects. Exposing their techniques for what they are is thus important.

- They ignore the scientific consensus.

- They cherry-pick their evidence.

- They rely on poor quality studies, opinion and anecdotes.

- They invent conspiracy theories.

- They defame their opponents.

- They point out that science has been wrong before.

- They say, ‘science does not know everything’.

Critical thinking is the best, perhaps even the only protection we have from being fooled and, crucially, from fooling ourselves. If my book enables you to question nonsense, call out untruths, correct falsehoods, ridicule stupidity, and disclose fake news, it surely was worth the effort.

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the impact of chiropractic utilization upon use of prescription opioids among patients with spinal pain. The researchers employed a retrospective cohort design for analysis of health claims data from three contiguous US states for the years 2012-2017.

They included adults aged 18-84 years enrolled in a health plan and with office visits to a primary care physician or chiropractor for spinal pain. Two cohorts of subjects were thus identified:

- patients who received both primary care and chiropractic care,

- Patients who received primary care but not chiropractic care.

The total number of subjects was 101,221. Overall, between 1.55 and 2.03 times more nonrecipients of chiropractic care filled an opioid prescription, as compared with recipients.

The authors concluded that patients with spinal pain who saw a chiropractor had half the risk of filling an opioid prescription. Among those who saw a chiropractor within 30 days of diagnosis, the reduction in risk was greater as compared with those with their first visit after the acute phase.

Similar findings have been reported before and we have discussed them on this blog (see here, here and here). As before, one has to ask: WHAT DO THEY ACTUALLY MEAN?

The short answer is NOTHING MUCH! And certainly not what many chiros make of them.

They do not suggest that chiropractic care is a substitute for opioids in the management of spinal pain.

Why?

There are several reasons. Perhaps the most important ones are that such analyses lack any clinical outcome data, and that comparing one mistake (opioid-overuse) whith what might be another (chiropractic care) is a wrong apporoach. Imagine a scenario where half to the patients had received, in addition to their usual care, the services of:

- a paranormal healer,

- a crystal therapist,

- a shaman,

- or a homeopath.

Nobody would be surprised to see a very similar result, particularly if all of these practitioners were in the habit of discouraging their patients from using conventional drugs. Or imagine a scenario where half of all patients suffering from spinal pain are entered into an environment where they receive no treatment at all. Who would not expect that this regimen does not dramatically reduce the risk of filling an opioid prescription? But would that indicate that zero treatment is a good solution for managing spinal pain?

The thing is this:

- If you want to reduce opioid use, you need to prescribe less opioids (for instance, by re-educating doctors to do as they have been told in med school and curb over-prescribing).

- If you discourage patients to use opioids (as many other healthcare professionals would), many will not use opioids.

- If you want to know whether chiropractic is effective in managing spinal pain, you need to conduct a well-designed clinical trial.

Or, to put it simply:

CORRELATION IS NOT CAUSATION!

During my almost 30 years of research into so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), I have published many papers which must have been severe disappointments to those who advocate SCAM or earn their living through it. Many SCAM proponents thus reacted with open hostility. Others tried to find flaws in those articles which they found most upsetting with a view of discrediting my work. The 2012 article entitled ‘A Replication of the Study ‘Adverse Effects of Spinal Manipulation: A Systematic Review‘ by the Australian chiropractor, Peter Tuchin, seems to be an example of the latter phenomenon (used recently by Jens Behnke in an attempt to defame me).

Here is the abstract of the Tuchin paper:

Objective: To assess the significance of adverse events after spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) by replicating and critically reviewing a paper commonly cited when reviewing adverse events of SMT as reported by Ernst (J Roy Soc Med 100:330-338, 2007).

Method: Replication of a 2007 Ernst paper to compare the details recorded in this paper to the original source material. Specific items that were assessed included the time lapse between treatment and the adverse event, and the recording of other significant risk factors such as diabetes, hyperhomocysteinemia, use of oral contraceptive pill, any history of hypertension, atherosclerosis and migraine.

Results: The review of the 32 papers discussed by Ernst found numerous errors or inconsistencies from the original case reports and case series. These errors included alteration of the age or sex of the patient, and omission or misrepresentation of the long term response of the patient to the adverse event. Other errors included incorrectly assigning spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) as chiropractic treatment when it had been reported in the original paper as delivered by a non-chiropractic provider (e.g. Physician).The original case reports often omitted to record the time lapse between treatment and the adverse event, and other significant clinical or risk factors. The country of origin of the original paper was also overlooked, which is significant as chiropractic is not legislated in many countries. In 21 of the cases reported by Ernst to be chiropractic treatment, 11 were from countries where chiropractic is not legislated.

Conclusion: The number of errors or omissions in the 2007 Ernst paper, reduce the validity of the study and the reported conclusions. The omissions of potential risk factors and the timeline between the adverse event and SMT could be significant confounding factors. Greater care is also needed to distinguish between chiropractors and other health practitioners when reviewing the application of SMT and related adverse effects.

The author of this ‘replication study’ claims to have identified several errors in my 2007 review of adverse effects of spinal manipulation. Here is the abstract of my article:

Objective: To identify adverse effects of spinal manipulation.

Design: Systematic review of papers published since 2001.

Setting: Six electronic databases.

Main outcome measures: Reports of adverse effects published between January 2001 and June 2006. There were no restrictions according to language of publication or research design of the reports.

Results: The searches identified 32 case reports, four case series, two prospective series, three case-control studies and three surveys. In case reports or case series, more than 200 patients were suspected to have been seriously harmed. The most common serious adverse effects were due to vertebral artery dissections. The two prospective reports suggested that relatively mild adverse effects occur in 30% to 61% of all patients. The case-control studies suggested a causal relationship between spinal manipulation and the adverse effect. The survey data indicated that even serious adverse effects are rarely reported in the medical literature.

Conclusions: Spinal manipulation, particularly when performed on the upper spine, is frequently associated with mild to moderate adverse effects. It can also result in serious complications such as vertebral artery dissection followed by stroke. Currently, the incidence of such events is not known. In the interest of patient safety we should reconsider our policy towards the routine use of spinal manipulation.

In my view, there are several things that are strange here:

- Tuchin published his paper 5 years after mine.

- He did not publish it in the same journal as my original, but in an obscure chiro journal that hardly any non-chiropractor would ever read.

- Tuchin never contacted me and never alerted me to his publication.

- The journal that Tuchin chose was not Medline-listed in 2012; consequently, I never got to know about the Tuchin article in a timely fashion. (Therefore, I did never respond to it.)

- A ‘replication study’ is a study that repeats the methodology of a previous study.

- Tuchin’s paper is therefore NOT a replication study. Firstly, mine was a review and not a study. Secondly, and crucially, Tuchin never repeated my methodology but used an entirely different one.

But arguably, these points are trivial. They should not distract from the fact that I might have made mistakes. So, let’s look at the substance of Tuchin’s claim, namely that I made errors or omissions in my review.

As to ‘omissions’, one could argue that a review such as mine will always have to omit some details in order to generate a concise summary. The only way to not omit any details is to re-publish all the primary papers in one large volume. Yet, this can hardly be the purpose of a systematic review.

As to the ‘errors’, it seems that the ages and sex of three patients were wrong (I have not checked this against the primary publications but, for the moment, I believe Tuchin). This is, of course, lamentable and – even though I have no idea whether the errors happened at the data extraction phase, during the typing, the revising, or the publishing of the paper – it is entirely my responsibility. I also seem to have mistaken a non-chiropractor for a chiropractor. This too is regrettable but, as the review was about spinal manipulation and not about chiropractic, the error is perhaps not so grave.

Be that as it may, these errors are unquestionably not good, and I can only apologise for them. If Tuchin had dealt with them in the usual way – by publishing in a timely fashion a ‘letter to the editor’ of the JRSM – I could have easily corrected them for everyone to see.

But I think there is a more important point to be made here:

Tuchin concludes his paper stating that it is unwise to make conclusions regarding causality from any case study or multiple case studies. The number of errors or omissions in the 2007 Ernst paper significantly limit any reported conclusions. I believe that both sentences are unjustified. The safety of any intervention in routine use has to be examined on the basis of published case studies. This is particularly true for chiropractic where no post-marketing surveillance similar to that for drugs exists.

The conclusions based on such evidence can, of course, never be firm, but they provide valuable signals that can prompt more rigorous investigations in the interest of patient safety. In view of such considerations, my own conclusions in my 2007 paper were, I think, correct and are NOT invalidated by my relatively trivial mistakes: spinal manipulation, particularly when performed on the upper spine, has repeatedly been associated with serious adverse events. Currently the incidence of such events is unknown. Adherence to informed consent, which currently seems less than rigorous, should therefore be mandatory to all therapists using this treatment. Considering that spinal manipulation is used mostly for self-limiting conditions and that its effectiveness is not well established, we should adopt a cautious attitude towards using it in routine health care.

And my conclusions in the abstract have now, I believe, become established wisdom. They are thus even less in jeopardy through my calamitous lapsus or Tuchin’s ‘replication study’: Spinal manipulation, particularly when performed on the upper spine, is frequently associated with mild to moderate adverse effects. It can also result in serious complications such as vertebral artery dissection followed by stroke. Currently, the incidence of such events is not known. In the interest of patient safety we should reconsider our policy towards the routine use of spinal manipulation.

Dry needling (DN), also known as myofascial trigger point dry needling, is a SCAM similar to acupuncture. It involves the use of solid filiform needles or hollow-core hypodermic needles and is usually employed for treating muscle pain. Instead of sticking them into acupuncture points, like with acupuncture, they are inserted into myofascial trigger points usually identified by palpation. There are some theories how DN might work, but whether it is clinically effective remains unclear.

This single-blind RCT determined, if the addition of upper quarter DN to a rehabilitation protocol is more effective in improving ROM, pain, and functional outcome scores when compared to a rehabilitation protocol alone after shoulder stabilization surgery. Thirty-nine post-operative shoulder patients were randomly allocated into two groups: (1) standard of care rehabilitation (control group) (2) standard of care rehabilitation plus dry needling (experimental group). Patient’s pain, ROM, and functional outcome scores were assessed at baseline (4 weeks post-operative), and at 8 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months post-operative.

Of 39 enrolled patients, 20 were allocated to the control group and 19 to the experimental group. At six-month follow up, there was a statistically significant improvement in shoulder flexion ROM in the control group. Aside from this, there were no significant differences in outcomes between the two treatment groups. Both groups showed improvement over time. No adverse events were reported.

The authors concluded that dry needling of the shoulder girdle in addition to standard of care rehabilitation after shoulder stabilization surgery did not significantly improve shoulder ROM, pain, or functional outcome scores when compared with standard of care rehabilitation alone. Both group’s improvement was largely equal over time. The significant difference in flexion at the six-month follow up may be explained by additional time spent receiving passive range of motion (PROM) in the control group. These results provide preliminary evidence that dry needling in a post-surgical population is safe and without significant risk of iatrogenic infection or other adverse events.

How odd!

This trial followed the infamous A+B versus B design. As [A+B] is more than [B] alone, one would have expected that the experimental group has a better outcome than the control group.

But this was not the case!

Why?

Theoretically it can mean one of two things:

- DN did not even convey a placebo effect.

- DN had a negative effect on the outcome.

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is usually a blood clot in a deep vein of a leg. It is a potentially life-threatening condition, because the clot can detach itself and end up in the lungs thus causing a pulmonary embolism which can be fatal. A DVT therefore is a medical emergency which is typically managed by immobilising the patient and putting him/her on anticoagulants.

Yet, homeopaths seem to have discovered another approach. Indian homeopaths just published a case report of a DVT in an old patient totally cured exclusively by the non-invasive method of treatment with micro doses of potentized homeopathic drugs selected on the basis of the totality of symptoms and individualization of the case. The authors concluded that, since this report is based on a single case of recovery, results of more such cases are warranted to strengthen the outcome of the present study.

The patient was advised by his doctor to have surgery which he refused. Instead, he consulted a homeopath who treated him homoeopathically. No conventional treatments were given. The patient recovered, yet his recovery is almost certainly unrelated to the homeopathics he received. Spontaneous recovery after DVT is not uncommon, and it is almost certain that it is this what the case report describes.

It is simply not plausible, nor is there evidence that homeopathy can alter the natural history of a DVT. This means that what the Indian homeopaths have described in their paper is nothing less than a case of gross negligence. Had the patient died of a pulmonary embolism due to an untreated DVT, it could have put them behind bars.

While it is, of course, most laudable that homeopaths have taken to publishing even their most serious errors, it would be more reassuring, if they developed some sort of insight into their mistakes. Instead, they seem naively confident and stupidly ignorant of the danger they pose to the public: homeopathy can play significant therapeutic roles in very serious diseases like DVT, provided the drugs are needs to be carefully selected on the basis of i) individualization of cases, ii) the totality of symptoms and personalized data, and iii) taking into consideration the pathogenicity level and proper diagnosis of the disease. Further, homeopathy may also be safely used in patients with conventional drug allergy (antibiotics) or other physical conditions preventing intake of conventional medicines.

My conclusion and recommendation: stay away from homeopaths, folks!

A team of chiropractic researchers conducted a review of the safety of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) in children under 10 years. They aimed to:

1) describe adverse events;

2) report the incidence of adverse events;

3) determine whether SMT increases the risk of adverse events compared to other interventions.

They searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Index to Chiropractic Literature from January 1, 1990 to August 1, 2019. Eligible studies were case reports/series, cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. Studies of high and acceptable methodological quality were included.

Most adverse events are mild (e.g., increased crying, soreness). One case report describes a severe adverse event (rib fracture in a 21-day-old) and another an indirect harm in a 4-month-old. The incidence of mild adverse events ranges from 0.3% (95% CI: 0.06, 1.82) to 22.22% (95% CI: 6.32, 54.74). Whether SMT increases the risk of adverse events in children is unknown.

The authors concluded that the risk of moderate and severe adverse events is unknown in children treated with SMT. It is unclear whether SMT increases the risk of adverse events in children < 10 years.

Thanks to their ingenious methodology, the authors managed to miss 11 of the 13 studies included in the review by Vohra et al which reported 9 serious adverse events and 20 cases of delayed diagnosis associated with SMT. Another review reported 15 serious adverse events and 775 mild to moderate adverse events following manual therapy. As far as I can see, the authors of the new review make just one reasonable point:

We recommend the implementation of a population-based active surveillance program to measure the incidence of severe and serious adverse events following SMT treatment in this population.

In the absence of such a surveillance system, any incidence figures are not just guess-work but also a depiction of the tip of a much bigger iceberg. So, why do the authors of this review not make this point clearly and powerfully? Why does the review read mostly like an attempt to white-wash a thorny subject? Why do they not provide a breakdown of the adverse events according to profession? The answer to these questions can be found at the very end of the paper:

This study was supported by the College of Chiropractors of British Columbia to Ontario Tech University. The College of Chiropractors of British Columbia was not involved in the design, conduct or interpretation of the research that informed the research. This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program to Pierre Côté who holds the Canada Research Chair in Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation at Ontario Tech University, and from the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation to Carol Cancelliere who holds a Research Chair in Knowledge Translation in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Ontario Tech University.

This study was supported by the College of Chiropractors of British Columbia to Ontario Tech University. The College of Chiropractors of British Columbia was not involved in the design, conduct or interpretation of the research that informed the research. This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program to Pierre Côté who holds the Canada Research Chair in Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation at Ontario Tech University, and funding from the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation to Carol Cancelliere who holds a Research Chair in Knowledge Translation in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Ontario Tech University.

I have often felt that chiropractic is similar to a cult. An investigation by cult members into the dealings of a cult is not the most productive of concepts, I guess.

The website of this organisation is always good for a surprise. A recent announcement relates to a course of Thought Field Therapy (TFT):

As part of our ongoing programme to explore prospects for improved healthcare, the College is pleased to announce a course on TFT – a “Tapping” therapy – independently provided by Janet Thomson MSc.

In healthcare we may find ourselves exhausting the evidence-based options and still looking for ways to help our patients. So when trusted practitioners suggest simple and safe approaches that appear to have benefit we are interested.

TFT is a simple non-invasive, technique that anyone can learn, for themselves or to pass on to their patients, to help cope with negative thoughts and emotions. It was developed by Roger Callahan who discovered that tapping on certain meridian points could help counter negative emotions. Janet trained with Roger and has become an accomplished exponent of the technique.

Janet has contracted her usual two-day course into one: to get the most from this will require access to her Tapping For Life book and there will be pre-course videos demonstrating some of the key techniques. The second consecutive day is available for advanced TFT training, to help in dealing with difficult cases, as well as how to integrate TFT with other modalities.

How much does it cost (excluding booking fee)? Day One only – £195; Day Two only – £195 (only available if you have previously completed day one); Both Days – £375.

When is it? Saturday & Sunday 7th-8th March – 09:30-17:30

What, you don’t know what TFT is? Let me fill you in.

According to Wiki, TFT is a fringe psychological treatment developed by an American psychologist, Roger Callahan.[2] Its proponents say that it can heal a variety of mental and physical ailments through specialized “tapping” with the fingers at meridian points on the upper body and hands. The theory behind TFT is a mixture of concepts “derived from a variety of sources. Foremost among these is the ancient Chinese philosophy of chi, which is thought to be the ‘life force’ that flows throughout the body”. Callahan also bases his theory upon applied kinesiology and physics.[3] There is no scientific evidence that TFT is effective, and the American Psychological Association has stated that it “lacks a scientific basis” and consists of pseudoscience.[2]

Other assessments are even less complimentary: Thought field therapy (TFT) is a New Age psychotherapy dressed up in the garb of traditional Chinese medicine. It was developed in 1981 by Dr. Roger Callahan, a cognitive psychologist. While treating a patient for water phobia:

He asked her to think about water, tap with two fingers on the point that connected with the stomach meridian and much to his surprise, her fear of water completely disappeared.*

Callahan attributes the cure to the tapping, which he thinks unblocked “energy” in her stomach meridian. I don’t know how Callahan got the idea that tapping on a particular point would have anything to do with relieving a phobia, but he claims he has developed taps for just about anything that ails you, including a set of taps that can cure malaria (NPR interview).

TFT allegedly “gives immediate relief for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD ), addictions, phobias, fears, and anxieties by directly treating the blockage in the energy flow created by a disturbing thought pattern. It virtually eliminates any negative feeling previously associated with a thought.”*

The theory behind TFT is that negative emotions cause energy blockage and if the energy is unblocked then the fears will disappear. Tapping acupressure points is thought to be the means of unblocking the energy. Allegedly, it only takes five to six minutes to elicit a cure. Dr. Callahan claims an 85% success rate. He even does cures over the phone using “Voice Technology” on infants and animals; by analyzing the voice he claims he can determine what points on the body the patient should tap for treatment.

_____________________________________________________________

Yes, TFT seems utterly implausible – but what about the clinical evidence?

There are quite a few positive controlled clinical trials of TFT. They all have one thing in common: they smell fishy to me! I know, that’s not a very scientific judgement. Let me rephrase it: I am not aware of a single trial that proves TFT to have effects beyond placebo (if you know one, please post the link).

And Janet Thomson, MSc (the therapist who runs the course), who is she? Her website is revealing; have a look if you are interested. If not, it might suffice to say that she modestly claims that she is an outstanding Life Coach, Therapist & Trainer.

So, considering that TFT is so very implausible and unproven, why does the ‘College of Medicine and Integrated Healthcare’ promote it in such strong terms?

I have to admit, I do not know the answer – perhaps they want at all costs to become known as the ‘College of Quack Medicine’?

About 85% of German children are treated with herbal remedies. Yet, little is known about the effects of such interventions. A new study might tell us more.

This analysis accessed 2063 datasets from the paediatric population in the PhytoVIS data base, screening for information on indication, gender, treatment, co-medication and tolerability. The results suggest that the majority of patients was treated with herbal medicine for the following conditions:

- common cold,

- fever,

- digestive complaints,

- skin diseases,

- sleep disturbances

- anxiety.

The perceived effect of the therapy was rated in 84% of the patients as very good or good without adverse events.

The authors concluded that the results confirm the good clinical effects and safety of herbal medicinal products in this patient population and show that they are widely used in Germany.

If you are a fan of herbal medicine, you will be jubilant. If, on the other hand, you are a critical thinker or a responsible healthcare professional, you might wonder what this database is, why it was set up and how exactly these findings were produced. Here are some details:

The data were collected by means of a retrospective, anonymous, one-off survey consisting of 20 questions on the user’s experience with herbal remedies. The questions included complaints/ disease, information on drug use, concomitant factors/diseases as well as basic patient data. Trained interviewers performed the interviews in pharmacies and doctor’s offices. Data were collected in the Western Part of Germany between April 2014 and December 2016. The only inclusion criterion was the intake of herbal drugs in the last 8 weeks before the individual interview. The primary endpoint was the effect and tolerability of the products according to the user.

And who participated in this survey? If I understand it correctly, the survey is based on a convenience sample of parents using herbal remedies. This means that those parents who had a positive experience tended to volunteer, while those with a negative experience were absent or tended to refuse. (Thus the survey is not far from the scenario I often use where people in a hamburger restaurant are questioned whether they like hamburgers.)

So, there are two very obvious factors other than the effectiveness of herbal remedies determining the results:

- selection bias,

- lack of objective outcome measure.

This means that conclusions about the clinical effects of herbal remedies in paediatric patients are quite simply not possible on the basis of this survey. So, why do the authors nevertheless draw such conclusions (without a critical discussion of the limitations of their survey)?

Could it have something to do with the sponsor of the research?

The PhytoVIS study was funded by the Kooperation Phytopharmaka GbR Bonn, Germany.

Or could it have something to do with the affiliations of the paper’s authors:

1 Institute of Pharmacy, University of Leipzig, Brüderstr. 34, 04103, Leipzig, Germny. [email protected].

2 Kooperation Phytopharmaka GbR, Plittersdorfer Str. 218, 573, Bonn, Germany. [email protected].

3 Institute of Medical Statistics and Computational Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne, Kerpener Str. 62, 50937, Cologne, Germany.

4 ClinNovis GmbH, Genter Str. 7, 50672, Cologne, Germany.

5 Bayer Consumer Health, Research & Development, Phytomedicines Supply and Development Center, Steigerwald Arzneimittelwerk GmbH, Havelstr. 5, 64295, Darmstadt, Germany.

6 Kooperation Phytopharmaka GbR, Plittersdorfer Str. 218, 53173, Bonn, Germany.

7 Institute of Pharmaceutical Biology, Goethe University Frankfurt, Max-von-Laue-Str. 9, 60438, Frankfurt, Germany.

8 Chair of Naturopathy, University Medicine Rostock, Ernst-Heydemann Str. 6, 18057, Rostock, Germany.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Chiropractors have a thing about treating children, babies and infants – not, I suspect, because it works but because it fills their bank accounts. To justify this abuse, they seem to go to any lengths – even to extrapolating from anecdote to evidence. This recently published case-report, for instance, described the chiropractic care of a neonate immediately post-partum who had experienced birth trauma.

Chiropractors have a thing about treating children, babies and infants – not, I suspect, because it works but because it fills their bank accounts. To justify this abuse, they seem to go to any lengths – even to extrapolating from anecdote to evidence. This recently published case-report, for instance, described the chiropractic care of a neonate immediately post-partum who had experienced birth trauma.

The attending midwife noted the infant had an asynclitic head presentation at birth and as a result was born with an elongation of the occiput due to cranial molding, bilateral flexion at the elbows and shoulders with decreased range of motion in the cervical spine with tongue and lip tie. Oedema of the occiput with bruising was notable along with hypertonicity of cervical musculature at C1, hypertonicity (bilaterally) of the pectoral and biceps muscles, blanching and tension of lip tie, decreased suck reflex and tongue retraction with sucking, fascial restrictions at the ethmoid bones, at the occipital condyles (bilaterally), as well as at the shoulders and clavicles, bilaterally. An anterior subluxation of left sphenoid was noted.

The infant was cared for with chiropractic including a sphenobasilar adjustment. Following this adjustment, significant reduction in occipital edema was noted along with normal suck pattern and breastfeeding normalized.

The authors concluded that this case report provides supporting evidence that patients suffering from birth trauma may benefit from subluxation-based chiropractic care.

Oh no, this case report provides nothing of the sort! If anything, it shows that some chiropractors are so deluded that they even publish their cases of child abuse. The poor infant would almost certainly have developed at least as well without a chiropractor having come anywhere near him/her. And if the infant had truly been in need of treatment, then not by a chiropractor (who has no knowledge or training in diagnosing or treating a new-born), but by a proper paediatrician.

I have been sceptical about Craniosacral Therapy (CST) several times (see for instance here, here and here). Now, a new paper might change all this:

The systematic review assessed the evidence of Craniosacral Therapy (CST) for the treatment of chronic pain. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of CST in chronic pain patients were eligible. Pain intensity and functional disability were the primary outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool.

Ten RCTs with a total of 681 patients suffering from neck and back pain, migraine, headache, fibromyalgia, epicondylitis, and pelvic girdle pain were included.

Compared to treatment as usual, CST showed greater post intervention effects on:

- pain intensity (SMD=-0.32, 95%CI=[−0.61,-0.02])

- disability (SMD=-0.58, 95%CI=[−0.92,-0.24]).

Compared to manual/non-manual sham, CST showed greater post intervention effects on:

- pain intensity (SMD=-0.63, 95%CI=[−0.90,-0.37])

- disability (SMD=-0.54, 95%CI=[−0.81,-0.28]) ;

Compared to active manual treatments, CST showed greater post intervention effects on:

- pain intensity (SMD=-0.53, 95%CI=[−0.89,-0.16])

- disability (SMD=-0.58, 95%CI=[−0.95,-0.21]) .

At six months, CST showed greater effects on pain intensity (SMD=-0.59, 95%CI=[−0.99,-0.19]) and disability (SMD=-0.53, 95%CI=[−0.87,-0.19]) versus sham. Secondary outcomes were all significantly more improved in CST patients than in other groups, except for six-month mental quality of life versus sham. Sensitivity analyses revealed robust effects of CST against most risk of bias domains. Five of the 10 RCTs reported safety data. No serious adverse events occurred. Minor adverse events were equally distributed between the groups.

The authors concluded that, in patients with chronic pain, this meta-analysis suggests significant and robust effects of CST on pain and function lasting up to six months. More RCTs strictly following CONSORT are needed to further corroborate the effects and safety of CST on chronic pain.

Robust effects! This looks almost convincing, particularly to an uncritical proponent of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). However, a bit of critical thinking quickly discloses numerous problems, not with this (technically well-made) review, but with the interpretation of its results and the conclusions. Let me mention a few that spring into my mind:

- The literature searches were concluded in August 2018; why publish the paper only in 2020? Meanwhile, there might have been further studies which would render the review outdated even on the day it was published. (I know that there are many reasons for such a delay, but a responsible journal editor must insist on an update of the searches before publication.)

- Comparisons to ‘treatment as usual’ do not control for the potentially important placebo effects of CST and thus tell us nothing about the effectiveness of CST per se.

- The same applies to comparisons to ‘active’ manual treatments and ‘non-manual’ sham (the purpose of a sham is to blind patients; a non-manual sham defies this purpose).

- This leaves us with exactly two trials employing a sham that might have been sufficiently credible to be able to fool patients into believing that they were receiving the verum.

- One of these trials (ref 44) is far too flimsy to be taken seriously: it was tiny (n=23), did not adequately blind patients, and failed to mention adverse effects (thus violating research ethics [I cannot take such trials seriously]).

- The other trial (ref 41) is by the same research group as the review, and the authors award themselves a higher quality score than any other of the primary studies (perhaps even correctly, because the other trials are even worse). Yet, their study has considerable weaknesses which they fail to discuss: it was small (n=54), there was no check to see whether patient-blinding was successful, and – as with all the CST studies – the therapist was, of course, no blind. The latter point is crucial, I think, because patients can easily be influenced by the therapists via verbal or non-verbal communication to report the findings favoured by the therapist. This means that the small effects seen in such studies are likely to be due to this residual bias and thus have nothing to do with the intervention per se.

- Despite the fact that the review findings depend critically on their own primary study, the authors of the review declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Considering all this plus the rather important fact that CST completely lacks biological plausibility, I do not think that the conclusions of the review are warranted. I much prefer the ones from my own systematic review of 2012. It included 6 RCTs (all of which were burdened with a high risk of bias) and concluded that the notion that CST is associated with more than non‐specific effects is not based on evidence from rigorous RCTs.

So, why do the review authors first go to the trouble of conducting a technically sound systematic review and meta-analysis and then fail utterly to interpret its findings critically? I might have an answer to this question. Back in 2016, I included the head of this research group, Gustav Dobos, into my ‘hall of fame’ because he is one of the many SCAM researchers who never seem to publish a negative result. This is what I then wrote about him:

Dobos seems to be an ‘all-rounder’ whose research tackles a wide range of alternative treatments. That is perhaps unremarkable – but what I do find remarkable is the impression that, whatever he researches, the results turn out to be pretty positive. This might imply one of two things, in my view:

- all alternative therapies are effective,

- the ‘Trustworthiness Index’ of Prof Dobos is unusual.

I let my readers chose which possibility they deem to be more likely.