bias

A recent blog-post pointed out that the usefulness of yoga in primary care is doubtful. Now we have new data to shed some light on this issue.

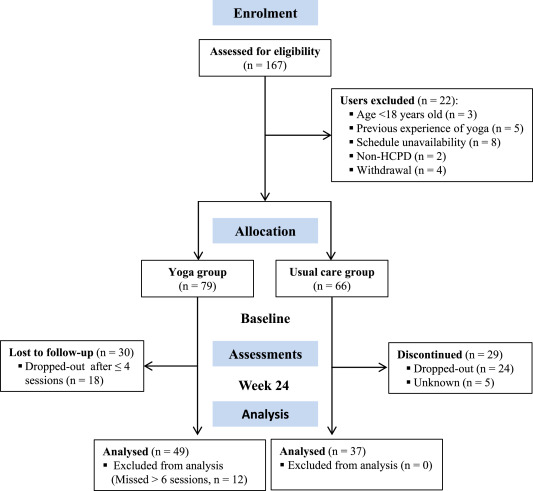

The new paper reports a ‘prospective, longitudinal, quasi-experimental study‘. Yoga group (n= 49) underwent 24-weeks program of one-hour yoga sessions. The control group had no yoga.

Participation was voluntary and the enrolment strategy was based on invitations by health professionals and advertising in the community (e.g., local newspaper, health unit website and posters). Users willing to participate were invited to complete a registration form to verify eligibility criteria.

The endpoints of the study were:

- quality of life,

- psychological distress,

- satisfaction level,

- adherence rate.

The yoga routine consisted of breathing exercises, progressive articular and myofascial warming-up, followed by surya namascar (sun salutation sequence; adapted to the physical condition of each participant), alignment exercises, and postural awareness. Practice also included soft twists of the spine, reversed and balance postures, as well as concentration exercises. During the sessions, the instructor discussed some ethical guidelines of yoga, as for example, non-violence (ahimsa) and truthfulness (satya), to allow the participant to have a safer and integrated practice. In addition, the participants were encouraged to develop their awareness of the present moment and their body sensations, through a continuous process of self-consciousness, keeping a distance between body sensations and the emotional experience. The instructor emphasized the connection between breathing and movement. Each session ended with a guided deep relaxation (yoga nidra; 5–10 min), followed by a meditation practice (5–10 min).

The results of the study showed that the patients in the yoga group experienced a significant improvement in all domains of quality of life and a reduction of psychological distress. Linear regression analysis showed that yoga significantly improved psychological quality of life.

The authors concluded that yoga in primary care is feasible, safe and has a satisfactory adherence, as well as a positive effect on psychological quality of life of participants.

Are the authors’ conclusions correct?

I think not!

Here are some reasons for my judgement:

- The study was far to small to justify far-reaching conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of yoga.

- There were relatively high numbers of drop-outs, as seen in the graph above. Despite this fact, no intention to treat analysis was used.

- There was no randomisation, and therefore the two groups were probably not comparable.

- Participants of the experimental group chose to have yoga; their expectations thus influenced the outcomes.

- There was no attempt to control for placebo effects.

- The conclusion that yoga is safe would require a sample size that is several dimensions larger than 49.

In conclusion, this study fails to show that yoga has any value in primary care.

PS

Oh, I almost forgot: and yoga is also satanic, of course (just like reading Harry Potter!).

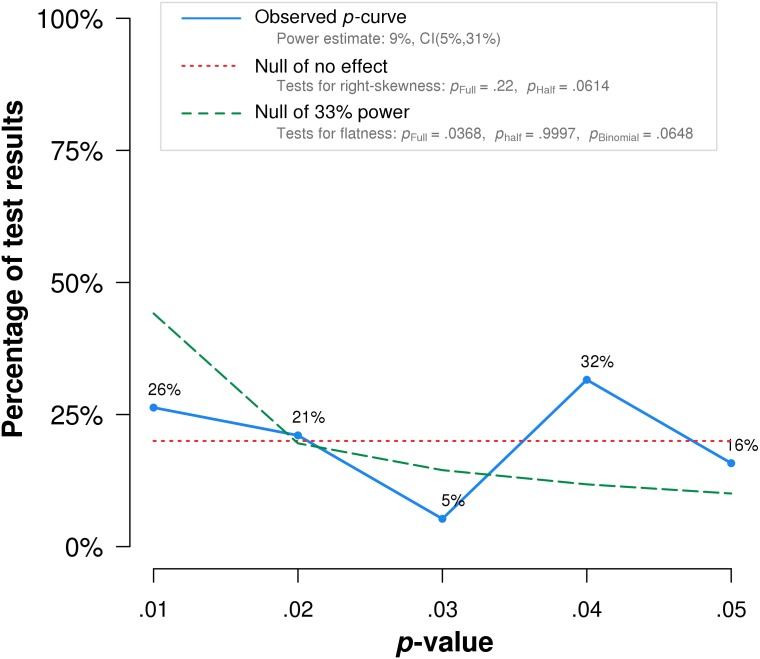

Researchers tend to report only studies that are positive, while leaving negative trials unpublished. This publication bias can mislead us when looking at the totality of the published data. One solution to this problem is the p-curve. A significant p-value indicates that obtaining the result within the null distribution is improbable. The p-curve is the distribution of statistically significant p-values for a set of studies (ps < .05). Because only true effects are expected to generate right-skewed p-curves – containing more low (.01s) than high (.04s) significant p-values – only right-skewed p-curves are diagnostic of evidential value. By telling us whether we can rule out selective reporting as the sole explanation for a set of findings, p-curve offers a solution to the age-old inferential problems caused by file-drawers of failed studies and analyses.

The authors of this article tested the distributions of sets of statistically significant p-values from placebo-controlled studies of homeopathic ultramolecular dilutions. Such dilute mixtures are unlikely to contain a single molecule of an active substance. The researchers tested whether p-curve accurately rejects the evidential value of significant results obtained in placebo-controlled clinical trials of homeopathic ultramolecular dilutions.

Their inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Study is accessible to the authors.

- Study is a clinical trial comparing ultramolecular dilutions to placebo.

- Study is randomized, with randomization method specified.

- Study is double-blinded.

- Study design and methodology result in interpretable findings (e.g., an appropriate statistical test is used).

- Study reports a test statistic for the hypothesis of interest.

- Study reports a discrete p-value or a test statistic from which a p-value can be derived.

- Study reports a p-value independent of other p-values in p-curve.

The first 20 studies, in the order of search output, that met the inclusion criteria were used for analysis.

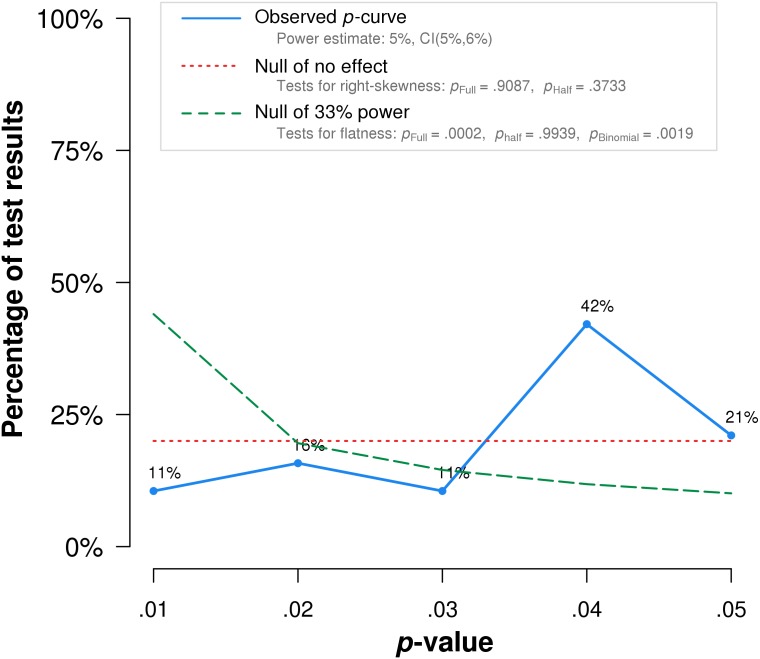

The researchers found that p-curve analysis accurately rejects the evidential value of statistically significant results from placebo-controlled, homeopathic ultramolecular dilution trials (1st graph below). This result indicates that replications of the trials are not expected to replicate a statistically significant result. A subsequent p-curve analysis was performed using the second significant p-value listed in the studies, if a second p-value was reported, to examine the robustness of initial results. P-curve rejects evidential value with greater statistical significance (2nd graph below). In essence, this seems to indicate that those studies of highly diluted homeopathics that reported positive findings, i. e. homeopathy is better than placebo, are false-positive results due to error, bias or fraud.

The authors’ conclusion: Our results suggest that p-curve can accurately detect when sets of statistically significant results lack evidential value.

The authors’ conclusion: Our results suggest that p-curve can accurately detect when sets of statistically significant results lack evidential value.

True effects with significant non-central distributions would have a greater density of low p-values than high p-values resulting in a right-skewed p-curve (like the dotted green lines in the above graphs). The fact that such a shape is not observed for studies of homeopathy confirms the many analyses previously demonstrating that ULTRAMOLECULAR HOMEOPATHIC REMEDIES ARE PLACEBOS.

Excellent journals always publish excellent science!

If this is what you believe, you might want to read a study of chiropractic just published in the highly respected SCIENTIFIC REPORTS.

The objective of this study was to investigate whether a single session of chiropractic care could increase strength in weak plantar flexor muscles in chronic stroke patients. Maximum voluntary contractions (strength) of the plantar flexors, soleus evoked V-waves (cortical drive), and H-reflexes were recorded in 12 chronic stroke patients, with plantar flexor muscle weakness, using a randomized controlled crossover design. Outcomes were assessed pre and post a chiropractic care intervention and a passive movement control. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to asses within and between group differences. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Following the chiropractic care intervention there was a significant increase in strength (F (1,11) = 14.49, p = 0.002; avg 64.2 ± 77.7%) and V-wave/Mmax ratio (F(1,11) = 9.67, p = 0.009; avg 54.0 ± 65.2%) compared to the control intervention. There was a significant strength decrease of 26.4 ± 15.5% (p = 0.001) after the control intervention. There were no other significant differences. Plantar flexor muscle strength increased in chronic stroke patients after a single session of chiropractic care. An increase in V-wave amplitude combined with no significant changes in H-reflex parameters suggests this increased strength is likely modulated at a supraspinal level. Further research is required to investigate the longer term and potential functional effects of chiropractic care in stroke recovery.

In the article we find the following further statements (quotes in bold, followed by my comments in normal print):

- Data were collected by a team of researchers from the Centre for Chiropractic Research at the New Zealand College of Chiropractic. These researchers can be assumed to be highly motivated in generating a positive finding.

- The entire spine and both sacroiliac joints were assessed for vertebral subluxations, and chiropractic adjustments were given where deemed necessary, by a New Zealand registered chiropractor. As there is now near-general agreement that such subluxations are a myth, the researchers treated a non-existing entity.

- The chiropractor did not contact on a segment deemed to be subluxated during the control set-up and no adjustive thrusts were applied during any control intervention. The patients therefore were clearly able to tell the difference between real and control treatments. Participants were not checked for blinding success.

- Maximum isometric plantarflexion force was measured using an isometric strain gauge. Such measurements crucially depend on the motivation of the patient.

- The grant proposal for this study was reviewed by the Australian Spinal Research Foundation to support facilitation of funding from the United Chiropractic Association. Does this not mean the researchers had a conflict of interest?

- The authors declare no competing interests. Really? They were ardent subluxationists supported by the United Chiropractic Association, an organisation stating that chiropractic is concerned with the preservation and restoration of health, and focuses particular attention on the subluxation, and subscribes to to the obsolete concept of vitalism: we ascribe to the idea that all living organisms are sustained by an innate intelligence, which is both different from and greater than physical and chemical forces. Further, we believe innate intelligence is an expression of universal intelligence.

So, in essence, what we have here is an under-powered study sponsored by vitalists and conducted by subluxationists treating a mythical entity with dubious interventions without controlling for patients’ expectation pretending their false-positive findings are meaningful.

I cannot help wondering what possessed the SCIENTIFIC REPORTS to publish such poor science.

Simply put, in the realm of SCAM, we seem to have two types of people:

- those who don’t care a hoot about evidence;

- those who try their best to follow the evidence.

The first group is replete with SCAM enthusiasts who make their decisions based purely on habit, emotion, intuition etc. They are beyond my reach, I fear. It is almost exclusively the second group for whom I write this blog.

And that could be relatively easy, if the evidence were always accessible, understandable, straight forward, conclusive and convincing. But sadly, in SCAM (as in most other areas of healthcare), the evidence is full of apparent and real contradictions. In this situation, it is often difficult even for experts to understand what is going on; for lay people this must be immeasurably more confusing. Yet, it is the lay consumers who often will take the decision to use or not use this or that SCAM. They therefore need our help.

What can consumers do when they are confronted with contradictory evidence?

How can they distinguish right from wrong?

- Some articles claim that homeopathy works – others say it is just a placebo therapy.

- Some experts claim that chiropractic is safe – others say it can do serious harm.

- Some articles claim that SCAM-practitioners are competent – others say this is not true.

- Some experts claim that SCAM is the future – others stress that it is obsolete.

What can a lay person with no or very little understanding of science do to see through this fog of contradictions?

Let me try to provide consumers with a step by step approach to get closer to the truth by asking a few incisive questions:

- WHERE DID YOU READ THE CLAIM? If it was in a newspaper, magazine, website, etc. take it with a pinch of salt (double the dose of salt, if it’s from the Daily Mail).

- CAN YOU RETRACE THE CLAIM TO A SCIENTIFIC PAPER? This might challenge you skills as a detective, but it is always well-worth finding the original source of a therapeutic claim in order to judge its credibility. If no good source can be found, I advise caution.

- IN WHICH MEDICAL JOURNAL WAS THE CLAIM PUBLISHED? Be aware of the fact that there are dozens of SCAM-journals that would publish virtually any rubbish.

- WHO ARE THE AUTHORS OF THE SCIENTIFIC PAPER? It might be difficult for a lay person to evaluate their credibility. But there might be certain pointers; for instance, authors affiliated to a university tend to be more credible than SCAM-practitioners who have no such affiliations or authors working for a lobby-group.

- WHAT SORT OF ARTICLE IS THE ORIGINAL SOURCE OF THE CLAIM? Is it a proper experimental study or a mere opinion piece? If possible, try to find a good-quality (perhaps even a Cochrane) review on the subject.

- ARE THERE OTHER RESEARCHERS WHO HAVE ARRIVED AT SIMILAR CONCLUSIONS? If the claim is based on just one solitary piece of research or opinion, it clearly weighs less than a consensus of experts.

- DO PUBLICATIONS EXIST THAT DISAGREE WITH THE CLAIM? Even if there are several scientific papers from different teams of researchers supporting the claim, it is important to find out whether the claim is shared by all experts in the field.

Eventually, you might get a good impression about the veracity of the claim. But sometimes you also might end up with a bunch of systematic reviews of which several support, while others reject the claim. And all of them could look similarly credible to your untrained eyes. Does that mean your attempt to find the truth of the matter has been frustrated?

Not necessarily!

In this case, you would probably consider the following options:

- You could do a simple ‘pea count’; this would tell you whether the majority of reviews is pro or contra the claim. However, this might be your worst bet for arriving at a sound conclusion. The quantity of the evidence usually is far less important than its quality.

- If you have no training to judge the quality of a review, you might just go with the most recent and up-to-date review. This, however, would also be fraught with problems, as you can, of course, not be sure that the most recent one is also the least biased assessment.

- Perhaps you can somehow get an impression about the respectability of the source. If, for instance, there is a recent Cochrane review, I advise to go with that one.

- Look up the profession of the authors of the review. The pope is unlikely to condemn Catholicism; likewise, you will find very few homeopaths who are critical of homeopathy, or chiropractors who are critical of chiropractic, etc. I know this is a very crude ‘last resort’ for replacing an authorative evaluation of the claim. But, if that’s all you have, it is better than nothing. Ask yourself who can normally be trusted more, the SCAM-practitioner or lobbyist who makes a living from the claim or an independent academic who has no such conflict of interest?

If all of this does not help you to decide whether a therapeutic claim is trustworthy or not, my advice has always been to reflect on this: IF IT SOUNDS TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE, IT PROBABLY IS.

In 2004, my team published a review analysing the diversity of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) research published in one single year (2002) across 7 European countries (Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, France, Spain, Netherlands, Belgium) and the US. In total 652 abstracts of articles were assessed. Germany and the UK were the only two European countries to publish in excess of 100 articles in that year (Germany: 137, UK: 183). The majority of articles were non-systematic reviews and comments, analytical studies and surveys. The UK carried out more surveys than any of the other countries and also published the largest number of systematic reviews. Germany, the UK and the US covered the widest range of interests across various SCAM modalities and investigated the safety of CAM. We concluded that important national differences exist in terms of the nature of SCAM research. This raises important questions regarding the reasons for such differences.

One striking difference was the fact that, compared to the UK, Germany had published far less research on SCAM that failed to report a positive result (4% versus 14%). Ever since, I have wondered why. Perhaps it has something to do with the biggest sponsor of SCAM research in Germany: THE CARSTENS STIFTUNG?

The Carstens Foundation (CF) was created by the former German President, Prof. Dr. Karl Carstens and his wife, Dr. Veronica Carstens. Karl Carstens (1914-1992) was the 5th President of federal Germany, from 1979 to 1984. Veronica Carstens (1923-2012) was a doctor of Internal Medicine with an interest in natural medicine and homeopathy in particular. She is quoted by the CF stating: „Der Arzt und die Ärztin der Zukunft sollen zwei Sprachen sprechen, die der Schulmedizin und die der Naturheilkunde und Homöopathie. Sie sollen im Einzelfall entscheiden können, welche Methode die besten Heilungschancen für den Patienten bietet.“ (Future doctors should speak two languages, that of ‘school medicine’ [Hahnemann’s derogatory term for conventional medicine] and that of naturopathy and homeopathy. They should be able to decide on a case by case basis which method offers the best chances of a cure for the patient.***)

Together, the two Carstens created the CF with the goal of sponsoring SCAM in Germany. More than 35 million € have so far been spent on more than 100 projects, fellowships, dissertations, an own publishing house, and a patient society “Natur und Medizin” (currently ~23 000 members) with the task of promoting SCAM. Projects the CF proudly list as their ‘milestones’ include:

- an outpatient clinic of natural medicine for cancer

- a project ‘Natural medicine and homeopathy for children and adolescents’.

The primary focus of the CF clearly is homeopathy, and it is in this area where their anti-science bias gets most obvious. I do invite everyone who reads German to have a look at their website and be amazed at the plethora of misleading claims.

Their expert for all things homeopathic is Dr Jens Behnke (‘Referent für Homöopathieforschung bei der Karl und Veronica Carstens-Stiftung: Evidenzbasierte Medizin, CAM, klinische Forschung, Grundlagenforschung’). He is not a medical doctor but has a doctorate from the ‘Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Europa-Universität Viadrina’ entitled ‘Wissenschaft und Weltanschauung. Eine epistemologische Analyse des Paradigmenstreits in der Homöopathieforschung’ (Science and world view. An epistemological analysis of the paradigm-quarrel in homeopathy research). His supervisor was Prof Harald Walach who has long been close to the CF.

Behnke claims to be an expert in EBM, clinical research and basic research but, intriguingly, he has not a single Medline-listed publication to his name. So, we only have his dissertation to assess his expertise.

The very 1st sentence of his dissertation is noteworthy, in my view: Die Homöopathie ist eine Therapiemethode, die seit mehr als 200 Jahren praktiziert wird und eine beträchtliche Zahl an Heilungserfolgen vorzuweisen hat (Homeopathy is a therapeutic method, that is being used since more than 200 years and which is supported by a remarkable number of therapeutic successes). In essence, the dissertation dismisses the scientific approach for evaluating homeopathy as well as the current best evidence that shows homeopathy to be ineffective.

Behnke dismisses my own research on homeopathy without even considering it. He first claims to have found an error in one of my systematic reviews and then states: Die Fragwürdigkeit der oben angeführten Methoden rechtfertigt das Übergehen sämtlicher Publikationen dieses Autors im Rahmen dieser Arbeit. Wenn einem Wissenschaftler die aufgezeigte absichtliche Falschdarstellung aufgrund von Voreingenommenheit nachgewiesen werden kann, sind seine Ergebnisse, wenn überhaupt, nur nach vorheriger systematischer Überprüfung sämtlicher Originalpublikationen und Daten, auf die sie sich beziehen, verwertbar. Essentially, he claims that, because he has found one error, the rest cannot be trusted and therefore he is entitled to reject the lot.

In the same dissertation, we read the following: Ernst konstatiert in allen … Arbeiten zur Homöopathie ausnahmslos, dass es keinerlei belastbare Hinweise auf eine Wirksamkeit homöopathischer Arzneimittel über Placeboeffekte hinaus gebe (Ernst states in all publications on homeopathy without exception that no solid suggestions exist at all for an effectiveness of homeopathic remedies). However, it is demonstrably wrong that all of my papers arrive at a negative judgement of homeopathy’s effectiveness; here are three that spring into my mind:

- There is evidence that homeopathic treatment can reduce the duration of ileus after abdominal or gynecologic surgery. However, several caveats preclude a definitive judgment. These results should form the basis of a randomized controlled trial to resolve the issue.

- Subjective complaints were relieved significantly more by Poikiven than by placebo. [Poikiven is a homeopathic remedy containing undiluted herbal ingredients, I hasten to add]

- … homeopathy works for certain conditions and is ineffective for others. [yes, I know! … (published in 1990)]

So, applying Behnke’s own logic outlined above, one should argue that, because I have found one error in his research, the rest of what Behnke will (perhaps one day be able to) publish cannot be trusted and therefore I am entitled to reject the lot.

That would, of course, be tantamount to adopting the stupidity of one’s own opponents. So, I will certainly not do that; instead, I will wait patiently for the sound science that Dr Behnke (and indeed the CF) might eventually produce.

***phraseology that is strikingly similar to that of Rudolf Hess on the same subject.

The Journal of Experimental Therapeutics and Oncology states that it is devoted to the rapid publication of innovative preclinical investigations on therapeutic agents against cancer and pertinent findings of experimental and clinical oncology. In the journal you will find review articles, original articles, and short communications on all areas of cancer research, including but not limited to preclinical experimental therapeutics; anticancer drug development; cancer biochemistry; biotechnology; carcinogenesis; cancer cytogenetics; clinical oncology; cytokine biology; epidemiology; molecular biology; pathology; pharmacology; tumor cell biology; and experimental oncology.

After reading an article entitled ‘How homeopathic medicine works in cancer treatment: deep insight from clinical to experimental studies’ in its latest issue, I doubt that the journal is devoted to anything.

Here is the abstract:

In the current scenario of medical sciences, homeopathy, the most popular system of therapy, is recognized as one of the components of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) across the world. Despite, a long debate is continuing whether homeopathy is just a placebo or more than it, homeopathy has been considered to be safe and cost-effectiveness therapeutic modality. A number of human ailments ranging from common to serious have been treated with homeopathy. However, selection of appropriate medicines against a disease is cumbersome task as total spectrum of symptoms of a patient guides this process. Available data suggest that homeopathy has potency not only to treat various types of cancers but also to reduce the side effects caused by standard therapeutic modalities like chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery. Although homeopathy has been widely used for management of cancers, its efficacy is still under question. In the present review, the anti-cancer effect of various homeopathic drugs against different kinds of cancers has been discussed and future course of action has also been suggested.

I do wonder what possessed the reviewers of this paper and the editors of the journal to allow such dangerous (and badly written) rubbish to get published. Do they not know that:

- homeopathy is a placebo therapy,

- homeopathy can not cure any cancer,

- cancer patients are highly vulnerable to false hope,

- such an article endangers the lives of many cancer patients,

- they have an ethical, moral and possibly legal duty to prevent such mistakes?

What makes this paper even more upsetting is the fact that one of its authors is affiliated with the Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

Family welfare my foot!

This certainly is one of the worst violations of healthcare and publication ethic that I have come across for a long time.

Robert Verkerk, Executive & scientific director, Alliance for Natural Health (ANH), seems to adore me (maybe that’s why I kept this post for Valentine’s Day?). In 2006, he published this article about me (it is lengthy, and I therefore shortened a bit, but feel free to study it in its full beauty):

START OF QUOTE

PROFESSOR EDZARD ERNST, the UK’s first professor of complementary medicine, gets lots of exposure for his often overtly negative views on complementary medicine. He’s become the media’s favourite resource for a view on this controversial subject…

The interesting thing about Prof Ernst is that he seems to have come a long way from his humble beginnings as a recipient of the therapies that he now seems so critical of. Profiled by Geoff Watts in the British Medical Journal, the Prof tells us: ‘Our family doctor in the little village outside Munich where I grew up was a homoeopath. My mother swore by it. As a kid I was treated homoeopathically. So this kind of medicine just came naturally. Even during my studies I pursued other things like massage therapy and acupuncture. As a young doctor I had an appointment in a homeopathic hospital, and I was very impressed with its success rate. My boss told me that much of this success came from discontinuing main stream medication. This made a big impression on me.’ (BMJ Career Focus 2003; 327:166; doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7425.s166)…

After his early support for homeopathy, Professor Ernst has now become, de facto, one of its main opponents. Robin McKie, science editor for The Observer (December 18, 2005) reported Ernst as saying, ‘Homeopathic remedies don’t work. Study after study has shown it is simply the purest form of placebo. You may as well take a glass of water than a homeopathic medicine.’ Ernst, having done the proverbial 180 degree turn, has decided to stand firmly shoulder to shoulder with a number of other leading assailants of non-pharmaceutical therapies, such as Professors Michael Baum and Jonathan Waxman. On 22 May 2006, Baum and twelve other mainly retired surgeons, including Ernst himself, bandied together and co-signed an open letter, published in The Times, which condemned the NHS decision to include increasing numbers of complementary therapies…

As high profile as the Ernsts, Baums and Waxmans of this world might be—their views are not unanimous across the orthodox medical profession. Some of these contrary views were expressed just last Sunday in The Sunday Times (Lost in the cancer maze, 10 December 2006)…

The real loser in open battles between warring factions in healthcare could be the consumer. Imagine how schizophrenic you could become after reading any one of the many newspapers that contains both pro-natural therapy articles and stinging attacks like that found in this week’s Daily Mail. But then again, we may misjudge the consumer who is well known for his or her ability to vote with the feet—regardless. The consumer, just like Robert Sandall, and the millions around the world who continue to indulge in complementary therapies, will ultimately make choices that work for them. ‘Survival of the fittest’ could provide an explanation for why hostile attacks from the orthodox medical community, the media and over-zealous regulators have not dented the steady increase in the popularity of alternative medicine.

Although we live in a technocratic age where we’ve handed so much decision making to the specialists, perhaps this is one area where the might of the individual will reign. Maybe the disillusionment many feel for pharmaceutically-biased healthcare is beginning to kick in. Perhaps the dictates from the white coats will be overruled by the ever-powerful survival instinct and our need to stay in touch with nature, from which we’ve evolved.

END OF QUOTE

Elsewhere, Robert Verkerk even called me the ‘master trickster of evidence-based medicine’ and stated that Prof Ernst and his colleagues appear to be evaluating the ‘wrong’ variable. As Ernst himself admitted, his team are focused on exploring only one of the variables, the ‘specific therapeutic effect’ (Figs 1 and 2). It is apparent, however, that the outcome that is of much greater consequence to healthcare is the combined effect of all variables, referred to by Ernst as the ‘total effect’ (Fig 1). Ernst does not appear to acknowledge that the sum of these effects might differ greatly between experimental and non-experimental situations.

Adding insult to injury, Ernst’s next major apparent faux pas involves his interpretation, or misinterpretation, of results. These fundamental problems exist within a very significant body of Prof Ernst’s work, particularly that which has been most widely publicised because it is so antagonistic towards healing cultures that have in many cases existed and evolved over thousands of years.

By example, a recent ‘systematic review’ of individualised herbal medicine undertaken by Ernst and colleagues started with 1345 peer-reviewed studies. However, all but three (0.2%) of the studies (RCTs) were rejected. These three RCTs in turn each involved very specific types of herbal treatment, targeting patients with IBS, knee osteoarthritis and cancer, the latter also undergoing chemotherapy, respectively. The conclusions of the study, which fuelled negative media worldwide, disconcertingly extended well beyond the remit of the study or its results. An extract follows: “Individualised herbal medicine, as practised in European medical herbalism, Chinese herbal medicine and Ayurvedic herbal medicine, has a very sparse evidence base and there is no convincing evidence that it is effective in any [our emphasis] indication. Because of the high potential for adverse events and negative herb-herb and herb-drug interactions, this lack of evidence for effectiveness means that its use cannot be recommended (Postgrad Med J 2007; 83: 633-637).

Robert Verkerk has recently come to my attention again – as the main author of a lengthy report published in December 2018. Its ‘Executive Summary’ makes the following points relevant in the context of this blog (the numbers in his text were added by me and refer to my comments below):

- This position paper proposes a universal framework, based on ecological and sustainability principles, aimed at allowing qualified health professionals (1), regardless of their respective modalities (disciplines), to work collaboratively and with full participation of the public in efforts to maintain or regenerate health and wellbeing. Accordingly, rather than offering ‘fixes’ for the NHS, the paper offers an approach that may significantly reduce the NHS’s current and growing disease burden that is set to reach crisis point given current levels of demand and funding.

- A major factor driving the relentlessly rising costs of the NHS is its over-reliance on pharmaceuticals (2) to treat a variety of preventable, chronic disorders. These (3) are the result — not of infection or trauma — but rather of our 21st century lifestyles, to which the human body is not well adapted. The failure of pharmaceutically-based approaches to slow down, let alone reverse, the dual burden of obesity and type 2 diabetes means wider roll-out of effective multi-factorial approaches are desperately needed (4).

- The NHS was created at a time when infectious diseases were the biggest killers (5). This is no longer the case, which is why the NHS must become part of a wider system that facilitates health regeneration or maintenance. The paper describes the major mechanisms underlying these chronic metabolic diseases, which are claiming an increasingly large portion of NHS funding. It identifies 12 domains of human health, many of which are routinely thrown out of balance by our contemporary lifestyles. The most effective way of treating lifestyle disorders is with appropriate lifestyle changes that are tailored to individuals, their needs and their circumstances. Such approaches, if appropriately supported and guided, tend to be far more economical and more sustainable as a means of maintaining or restoring people’s health (6).

- A sustainable health system, as proposed in this position paper, is one in which the individual becomes much more responsible for maintaining his or her own health and where more effort is invested earlier in an individual’s life prior to the downstream manifestation of chronic, degenerative and preventable diseases (7). Substantially more education, support and guidance than is typically available in the NHS today will need to be provided by health professionals (1), informed as necessary by a range of markers and diagnostic techniques (8). Healthy dietary and lifestyle choices and behaviours (9) are most effective when imparted early, prior to symptoms of chronic diseases becoming evident and before additional diseases or disorders (comorbidities) have become deeply embedded.

- The timing of the position paper’s release coincides not only with a time when the NHS is in crisis, but also when the UK is deep in negotiations over its extraction from the European Union (EU). The paper includes the identification of EU laws that are incompatible with sustainable health systems, that the UK would do well to reject when the time comes to re-consider the British statute books following the implementation of the Great Repeal Bill (10).

- This paper represents the first comprehensive attempt to apply sustainability principles to the management of human health in the context of our current understanding of human biology and ecology, tailored specifically to the UK’s unique situation. It embodies approaches that work with, rather than against, nature (11). Sustainability principles have already been applied successfully to other sectors such as energy, construction and agriculture.

- It is now imperative that the diverse range of interests and specialisms (12) involved in the management of human health come together. We owe it to future generations to work together urgently, earnestly and cooperatively to develop and thoroughly evaluate new ways of managing and creating health in our society. This blueprint represents a collaborative effort to give this process much needed momentum.

My very short comments:

- I fear that this is meant to include SCAM-practitioners who are neither qualified nor skilled to tackle such tasks.

- Dietary supplements (heavily promoted by the ANH) either have pharmacological effects, in which case they too must be seen as pharmaceuticals, or they are useless, in which case we should not promote them.

- I think ‘some of these’ would be more correct.

- Multifactorial yes, but we must make sure that useless SCAMs are not being pushed in through the back-door. Quackery must not be allowed to become a ‘factor’.

- Only, if we discount cancer and arteriosclerosis, I think.

- SCAM-practitioners have repeatedly demonstrated to be a risk to public health.

- All we know about disease prevention originates from conventional medicine and nothing from SCAM.

- Informed by…??? I would prefer ‘based on evidence’ (evidence being one term that the report does not seem to be fond of).

- All healthy dietary and lifestyle choices and behaviours that are backed by good evidence originate from and are part of conventional medicine, not SCAM.

- Do I detect the nasty whiff a pro-Brexit attitude her? I wonder what the ANH hopes for in a post-Brexit UK.

- The old chestnut of conventional medicine = unnatural and SCAM = natural is being warmed up here, it seems to me. Fallacy galore!

- The ANH would probably like to include a few SCAM-practitioners here.

Call me suspicious, but to me this ANH-initiative seems like a clever smoke-screen behind which they hope to sell their useless dietary supplements and homeopathic remedies to the unsuspecting British public. Am I mistaken?

If so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) ever were to enter the Guinness Book of Records, it would most certainly be because it generates more surveys than any other area of medical inquiry. I have long been rather sceptical about this survey-mania. Therefore, I greet any major new survey with some trepidation.

The aim of this new survey was to obtain up-to-date general population figures for practitioner-led SCAM use in England, and to discover people’s views and experiences regarding access. The researchers commissioned a face-to-face questionnaire survey of a nationally representative adult quota sample (aged ≥15 years). Ten questions were included within Ipsos MORI’s weekly population-based survey. The questions explored 12-month practitioner-led SCAM use, reasons for non-use, views on NHS-provided SCAM, and willingness to pay.

Of 4862 adults surveyed, 766 (16%) had seen a SCAM practitioner. People most commonly visited SCAM practitioners for manual therapies (massage, osteopathy, chiropractic) and acupuncture, as well as yoga, pilates, reflexology, and mindfulness or meditation. Women, people with higher socioeconomic status (SES) and those in south England were more likely to access SCAM. Musculoskeletal conditions (mainly back pain) accounted for 68% of use, and mental health 12%. Most was through self-referral (70%) and self-financing. GPs (17%) or NHS professionals (4%) referred and/or recommended SCAM to users. These SCAM users were more often unemployed, with lower income and social grade, and receiving NHS-funded SCAM. Responders were willing to pay varying amounts for SCAM; 22% would not pay anything. Almost two in five responders felt NHS funding and GP referral and/or endorsement would increase their SCAM use.

The authors concluded that SCAM is commonly used in England, particularly for musculoskeletal and mental health problems, and by affluent groups paying privately. However, less well-off people are also being GP-referred for NHS-funded treatments. For SCAM with evidence of effectiveness (and cost-effectiveness), those of lower SES may be unable to access potentially useful interventions, and access via GPs may be able to address this inequality. Researchers, patients, and commissioners should collaborate to research the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SCAM, and consider its availability on the NHS.

I feel that a few critical thoughts are in order:

- The authors call their survey an ‘up-date’. The survey ran between 25 September and 18 October 2015. That is more than three years ago. I would not exactly call this an up-date!

- Authors (several of whom are known SCAM-enthusiasts) also state that practitioner-led SCAM use was about 5% higher than previous national (UK and England) surveys. This may relate to the authors’ wider SCAM definition, which included 11 more therapies than Hunt et al (a survey from my team), or increased SCAM use since 2005. Despite this uncertainty, the authors write this: Figures from 2005 reported that 12% of the English population used practitioner-led CAM. This 2015 survey has found that 16% of the general population had used practitioner-led CAM in the previous 12 months. Thus, they imply that SCAM-use has been increasing.

- The main justification for running yet another survey presumably was to determine whether SCAM-use has increased, decreased or remained the same (virtually everything else found in the new survey had been shown many times before). To not answer this main question conclusively by asking the same questions as a previous survey is just daft, in my view. We have used the same survey methods at two points one decade apart and found little evidence for an increase, on the contrary: overall, GPs were less likely to endorse CAMs than previously shown (38% versus 19%).

- The main reason why I have long been critical about such surveys is the manner in which their data get interpreted. The present paper is no exception in this respect. Invariably the data show that SCAM is used by those who can afford it. This points to INEQUALITY that needs to be addressed by allowing much more SCAM on the public purse. In other words, such surveys are little more that very expensive and somewhat under-hand promotion of quackery.

- Yes, I know, the present authors are more clever than that; they want the funds limited to SCAM with evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. So, why do they not list those SCAMs together with the evidence for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness? This would enable us to check the validity of the claim that more public money should fund SCAM. I think I know why: such SCAMs do not exist or, at lest, they are extremely rare.

But otherwise the new survey was excellent.

The PGIH (currently chaired by the Tory MP David Tredinnick) was founded in 1992 (in the mid 1990, they once invited me to give a lecture which I did with pleasure). Its overriding aim is to bring about improvements in patient care. The PGIH have conducted a consultation that involved 113 SCAM-organisations and other stakeholders. The new PGIH-report is based on their feedback and makes 14 recommendations. They are all worth studying but, to keep this post concise, I have selected the three that fascinated me most:

Evidence Base and Research

NICE guidelines are too narrow and do not fit well with models of care such as complementary, traditional and natural therapies, and should incorporate qualitative evidence and patient outcomes measures as well as RCT evidence. Complementary, traditional and natural healthcare associations should take steps to educate and advise their members on the use of Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profiles (MYMOP), and patient outcome measures should be collated by an independent central resource to identify for what conditions patients are seeking treatment, and with what outcomes.

Cancer Care

Every cancer patient and their families should be offered complementary therapies as part of their treatment package to support them in their cancer journey. Cancer centres and hospices providing access to complementary therapies should be encouraged to make wider use of Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCaW) to evaluate the benefits gained by patients using complementary therapies in cancer support care. Co-ordinated research needs to be carried out, both clinical trials and qualitative studies, on a range of complementary, traditional and natural therapies used in cancer care support.

Cost Savings

The government should run NHS pilot projects which look at non-conventional ways of treating patients with long-term and chronic conditions affected by Effectiveness Gaps, such as stress, arthritis, asthma and musculoskeletal problems, and audit these results against conventional treatment options for these conditions to determine whether cost savings and better patient outcomes could be achieved.

END OF QUOTE

Here are a few brief comments on those three recommendations.

Evidence base and research

NICE guidelines are based on rigorous assessments of efficacy, safety and costs. Such evaluations are possible for all interventions, including SCAM. Qualitative data are useless for this purpose. Outcome measures like the MYMOP are measures that can and are used in clinical trials. To use them outside clinical trials would not provide any relevant information about the specific effects of SCAM because this cannot account for confounding factors like the natural history of the disease, regression towards the mean, etc. The entire paragraph disclosed a remarkable level of naivety and ignorance about research on behalf of the PGIH.

Cancer care

There is already a significant amount of research on SCAM for cancer (see for instance here). It shows that no SCAM is effective in curing any form of cancer, and that only very few SCAMs can effectively improve the quality of life of cancer patients. Considering these facts, the wholesale recommendation of offering SCAM to cancer patients can only be characterised as dangerous quackery.

Cost savings

Such a pilot project has already been conducted at the behest of Price Charles (see here). Its results show that flimsy research will generate flimsy findings. If anything, a rigorous trial would be needed to test whether more SCAM on the NHS saves or costs money. The data currently available suggests that the latter is the case (see also here, here, here, here, etc.).

Altogether, one gets the impression that the PGIH need to brush up on their science and knowledge (if they invite me, I’d be delighted to give them another lecture). As it stands, it seems unlikely that their approach will, in fact, bring about improvements in patient care.

The objective of this ‘real world’ study was to evaluate the effectiveness of integrative medicine (IM) on patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and investigate the prognostic factors of CAD in a real-world setting.

A total of 1,087 hospitalized patients with CAD from 4 hospitals in Beijing, China were consecutively selected between August 2011 and February 2012. The patients were assigned to two groups:

- Chinese medicine (CM) plus conventional treatment, i.e., IM therapy (IM group). IM therapy meant that the patients accepted the conventional treatment of Western medicine and the treatment of Chinese herbal medicine including herbal-based injection and Chinese patent medicine as well as decoction for at least 7 days in the hospital or 3 months out of the hospital.

- Conventional treatment alone (CT group).

The endpoint was a major cardiac event [MCE; including cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), and the need for revascularization].

A total of 1,040 patients finished the 2-year follow-up. Of them, 49.4% received IM therapy. During the 2-year follow-up, the total incidence of MCE was 11.3%. Most of the events involved revascularization (9.3%). Cardiac death/MI occurred in 3.0% of cases. For revascularization, logistic stepwise regression analysis revealed that age ⩾ 65 years [odds ratio (OR), 2.224], MI (OR, 2.561), diabetes mellitus (OR, 1.650), multi-vessel lesions (OR, 2.554), baseline high sensitivity C-reactive protein level ⩾ 3 mg/L (OR, 1.678), and moderate or severe anxiety/depression (OR, 1.849) were negative predictors (P<0.05); while anti-platelet agents (OR, 0.422), β-blockers (OR, 0.626), statins (OR, 0.318), and IM therapy (OR, 0.583) were protective predictors (P<0.05). For cardiac death/MI, age ⩾ 65 years (OR, 6.389) and heart failure (OR, 7.969) were negative predictors (P<0.05), while statin use (OR, 0.323) was a protective predictor (P<0.05) and IM therapy showed a beneficial tendency (OR, 0.587), although the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.218).

The authors concluded that in a real-world setting, for patients with CAD, IM therapy was associated with a decreased incidence of revascularization and showed a potential benefit in reducing the incidence of cardiac death or MI.

What the authors call ‘real world setting’ seems to be a synonym of ‘lousy science’, I fear. I am not aware of good evidence to show that herbal injections and concoctions are effective treatments for CAD, and this study can unfortunately not change this. In the methods section of the paper, we read that the treatment decisions were made by the responsible physicians without restriction. That means the two groups were far from comparable. In their discussion section, the authors state; we found that IM therapy was efficacious in clinical practice. I think that this statement is incorrect. All they have shown is that two groups of patients with similar diagnoses can differ in numerous ways, including clinical outcomes.

The lessons here are simple:

- In clinical trials, lack of randomisation (the only method to create reliably comparable groups) often leads to false results.

- Flawed research is currently being used by many proponents of SCAM (so-called alternative medicine) to mislead us about the value of SCAM.

- The integration of dubious treatments into routine care does not lead to better outcomes.

- Integrative medicine, as currently advocated by SCAM-proponents, is a nonsense.