bias

Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (CSMT) for migraine?

Why?

There is no good evidence that it works!

On the contrary, there is good evidence that it does NOT work!

A recent and rigorous study (conducted by chiropractors!) tested the efficacy of chiropractic CSMT for migraine. It was designed as a three-armed, single-blinded, placebo -controlled RCT of 17 months duration including 104 migraineurs with at least one migraine attack per month. Active treatment consisted of CSMT (group 1) and the placebo was a sham push manoeuvre of the lateral edge of the scapula and/or the gluteal region (group 2). The control group continued their usual pharmacological management (group 3). The results show that migraine days were significantly reduced within all three groups from baseline to post-treatment. The effect continued in the CSMT and placebo groups at all follow-up time points (groups 1 and 2), whereas the control group (group 3) returned to baseline. The reduction in migraine days was not significantly different between the groups. Migraine duration and headache index were reduced significantly more in the CSMT than in group 3 towards the end of follow-up. Adverse events were few, mild and transient. Blinding was sustained throughout the RCT. The authors concluded that the effect of CSMT observed in our study is probably due to a placebo response.

One can understand that, for chiropractors, this finding is upsetting. After all, they earn a good part of their living by treating migraineurs. They don’t want to lose patients and, at the same time, they need to claim to practise evidence-based medicine.

What is the way out of this dilemma?

Simple!

They only need to publish a review in which they dilute the irritatingly negative result of the above trial by including all previous low-quality trials with false-positive results and thus generate a new overall finding that alleges CSMT to be evidence-based.

This new systematic review of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) evaluated the evidence regarding spinal manipulation as an alternative or integrative therapy in reducing migraine pain and disability.

The searches identified 6 RCTs eligible for meta-analysis. Intervention duration ranged from 2 to 6 months; outcomes included measures of migraine days (primary outcome), migraine pain/intensity, and migraine disability. Methodological quality varied across the studies. The results showed that spinal manipulation reduced migraine days with an overall small effect size as well as migraine pain/intensity.

The authors concluded that spinal manipulation may be an effective therapeutic technique to reduce migraine days and pain/intensity. However, given the limitations to studies included in this meta-analysis, we consider these results to be preliminary. Methodologically rigorous, large-scale RCTs are warranted to better inform the evidence base for spinal manipulation as a treatment for migraine.

Bob’s your uncle!

Perhaps not perfect, but at least the chiropractic profession can now continue to claim they practice something akin to evidence-based medicine, while happily cashing in on selling their unproven treatments to migraineurs!

But that’s not very fair; research is not for promotion, research is for finding the truth; this white-wash is not in the best interest of patients! I hear you say.

Who cares about fairness, truth or conflicts of interest?

Christine Goertz, one of the review-authors, has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the Director of the Inter‐Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR). Peter M. Wayne, another author, has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the co‐Director of the Inter‐Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR)

And who the Dickens are the NCMIC and the IINCR?

At NCMIC, they believe that supporting the chiropractic profession, including chiropractic research programs and projects, is an important part of our heritage. They also offer business training and malpractice risk management seminars and resources to D.C.s as a complement to the education provided by the chiropractic colleges.

The IINCR is a collaborative effort between PCCR, Yale Center for Medical Informatics and the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. They aim at creating a chiropractic research portfolio that’s truly translational. Vice Chancellor for Research and Health Policy at Palmer College of Chiropractic Christine Goertz, DC, PhD (PCCR) is the network director. Peter Wayne, PhD (Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School) will join Anthony J. Lisi, DC (Yale Center for Medical Informatics and VA Connecticut Healthcare System) as a co-director. These investigators will form a robust foundation to advance chiropractic science, practice and policy. “Our collective efforts provide an unprecedented opportunity to conduct clinical and basic research that advances chiropractic research and evidence-based clinical practice, ultimately benefiting the patients we serve,” said Christine Goertz.

Really: benefiting the patients?

You could have fooled me!

The aim of this new systematic review was to evaluate the controlled trials of homeopathy in bronchial asthma. Relevant trials published between Jan 1, 1981, and Dec 31, 2016, were considered. Substantive research articles, conference proceedings, and master and doctoral theses were eligible. Methodology was assessed by Jadad’s scoring, internal validity by the Coch-rane tool, model validity by Mathie’s criteria, and quality of individualization by Saha’s criteria.

Sixteen trials were eligible. The majority were positive, especially those testing complex formulations. Methodological quality was diverse; 8 trials had “high” risk of bias. Model validity and individualization quality were compromised. Due to both qualitative and quantitative inadequacies, proofs supporting individualized homeopathy remained inconclusive. The trials were positive (evidence level A), but inconsistent, and suffered from methodological heterogeneity, “high” to “uncertain” risk of bias, incomplete study reporting, inadequacy of independent replications, and small sample sizes.

The authors of this review come from:

- the Department of Homeopathy, District Joint Hospital, Government of Bihar, Darbhanga, India;

- the Department of Organon of Medicine and Homoeopathic Philosophy, Sri Sai Nath Postgraduate Institute of Homoeopathy, Allahabad, India;

- the Homoeopathy University Jaipur, Jaipur, India;

- the Central Council of Homeopathy, Hooghly,

- the Central Council of Homeopathy, Howrah, India

They state that they have no conflicts of interest.

The review is puzzling on so many accounts that I had to read it several times to understand it. Here are just some of its many oddities:

- According to its authors, the review adhered to the PRISMA-P guideline; as a co-author of this guideline, I can confirm that this is incorrect.

- The authors claim to have included all ‘controlled trials (randomized, non-randomized, or observational) of any form of homeopathy in patients suffering from persistent and chronic bronchial asthma’. In fact, they also included uncontrolled studies (16 controlled trials and 12 uncontrolled observational studies, to be precise).

- The authors included papers published between Jan 1, 1981, and Dec 31, 2016. It is unacceptable, in my view, to limit a systematic review in this way. It also means that the review was seriously out of date already on the day it was published.

- The authors tell us that they applied no language restrictions. Yet they do not inform us how they handled papers in foreign languages.

- Studies of homeopathy as a stand alone therapy were included together with studies of homeopathy as an adjunct. Yet the authors fail to point out which studies belonged to which category.

- Several of the included studies are not of homeopathy but of isopathy.

- The authors fail to detail their results and instead refer to an ‘online results table’ which I cannot access even though I have the on-line paper.

- Instead, they report that 28 studies were included and ‘thus, the level of evidence was graded as A.’

- No direction of outcome was provided in the results section. All we do learn from the paper’s discussion section is that ‘the majority of the studies were positive, and the level of evidence could be graded as A (strong scientific evidence)’.

- Despite the high risk of bias in most of the included studies, the authors suggest a ‘definite role of homeopathy beyond placebo in the treatment of bronchial asthma’.

- The current Cochrane review (also authored by a pro-homeopathy team) concluded that there is not enough evidence to reliably assess the possible role of homeopathy in asthma. Yet the authors of this new review do not even attempt to explain the contradiction.

Confusion?

Incompetence?

Scientific misconduct?

Fraud?

YOU DECIDE!

The aim of this systematic review was to determine the efficacy of conventional treatments plus acupuncture versus conventional treatments alone for asthma, using a meta-analysis of all published randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

The researchers included all RCTs in which adult and adolescent patients with asthma (age ≥12 years) were divided into conventional treatments plus acupuncture (A+B) and conventional treatments (B). Nine studies were included. The results showed that A+B could improve the symptom response rate and significantly decrease interleukin-6. However, indices of pulmonary function, including the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) failed to be improved with A+B.

The authors concluded that conventional treatments plus acupuncture are associated with significant benefits for adult and adolescent patients with asthma. Therefore, we suggest the use of conventional treatments plus acupuncture for asthma patients.

I am thankful to the authors for confirming my finding that A+B must always be more/better than B alone (the 2nd sentence of their conclusion is, of course, utter nonsense, but I will leave this aside for today). Here is the short abstract of my 2008 article:

In this article, we test the hypothesis that randomized clinical trials of acupuncture for pain with certain design features (A + B versus B) are likely to generate false positive results. Based on electronic searches in six databases, 13 studies were found that met our inclusion criteria. They all suggested that acupuncture is effective (one only showing a positive trend, all others had significant results). We conclude that the ‘A + B versus B’ design is prone to false positive results and discuss the design features that might prevent or exacerbate this problem.

Even though our paper was on acupuncture for pain, it firmly established the principle that A+B is always more than B. Think of it in monetary terms: let’s say we both have $100; now someone gives me $10 more. Who has more cash? Not difficult, is it?

But why do SCAM-fans not get it?

Why do we see trial after trial and review after review ignoring this simple and obvious fact?

I suspect I know why: it is because the ‘A+B vs B’ study-design never generates a negative result!

But that’s cheating!

And isn’t cheating unethical?

My answer is YES!

(If you want to read a more detailed answer, please read our in-depth analysis here)

I have just given two lectures on so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) in France.

Why should that be anything to write home about?

Perhaps it isn’t; but during the last 25 years I have been lecturing all over the world and, even though I live partly in France and speak the language, I never attended a single SCAM-conference there. I have tried for a long time to establish contact with French SCAM-researchers, but somehow this never happened.

Eventually, I came to the conclusion that, although the practice of SCAM is hugely popular in this country, there was no or very little SCAM-research in France. This conclusion seems to be confirmed by simple Medline searches. For instance, Medline lists just 171 papers for ‘homeopathy/France’ (homeopathy is much-used in France), while the figures for Germany and the UK are 490 and 448.

These are, of course, only very rough indicators, and therefore I was delighted to be invited to participate for the first time in a French SCAM-conference. It was well-organised, and I am most grateful to the organisers to have me. Actually, the meeting was about non-pharmacological treatments but the focus was clearly on SCAM. Here are a few impressions purely on the SCAM-elements of this conference.

TERMINOLOGY

Already the title of the conference, ‘Non-pharmacological Interventions: Integrative, Preventive, Complementary and Personalised Medicines‘, contained a confusing shopping-list of terms. The actual lectures offered even more. Clear definitions of these terms were not forthcoming and are, as far as I can see, impossible. This meant that much of the discussion lacked focus. In both my presentations, I used the term ‘alternative medicine’ and stressed that all such umbrella terms are fairly useless. In my view, it is therefore best to name the precise modality (acupuncture, osteopathy, homeopathy etc.) one wants to discuss.

INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE

The term that seemed to dominate the conference was ‘INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE’ (IM). I got the impression that it was employed uncritically by some for bypassing the need for proper evaluation of any specific SCAM. The experts seemed to imply that, because IM is the politically and socially correct approach, there is no longer a need for asking whether the treatments to be integrated actually generate more good than harm. I got the impression that most of these researchers were confusing science with promotion.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The discussions regularly touched upon research methodology – but they did little more than lightly touch it. People tended to lament that ‘conventional research methodology’ was inadequate for assessing SCAM, and that we therefore needed different methods and even paradigms. I did not hear any reasonable explanations in what respect the ‘conventional methodology’ might be insufficient, nor did I understand the concept of an alternative science or paradigm. My caution that double standards in medicine can only be detrimental, seemed to irritate and fell mostly on deaf ears.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

My own research agenda has always been the efficacy and safety of SCAM; and I still have no doubt that these are the issues that need addressing more urgently than any others. My impression was that, during this conference, the researchers seemed to aim in entirely different directions. One speaker even explained that, if a homeopath is fully convinced of the assumptions of homeopathy, he is entirely within the ethical standards to treat his patients homeopathically, regardless of the fact that homeopathy is demonstrably wrong. Another speaker claimed that there is no doubt any longer about the efficacy of acupuncture; the research question therefore must be how to best implement it in routine healthcare. And yet another expert tried to explain TCM with quantum physics. I have, of course, heard similar nonsense before during such conferences, but rarely did it pass without objection or debate.

RESEARCH FUNDING

The lack of research funding was bemoaned repeatedly. Most researchers seemed to think that they needed dedicated funding streams for SCAM to take account of the need of softer methodologies and the unique nature of SCAM. The argument that there should be only one set of standards for spending scarce research funds – scientific rigor and relevance – was not one shared by the French SCAM enthusiasts. The US example was frequently cited as the one that we ought to follow. In my view, the US example foremost shows impressively that a ring-fenced funding stream for SCAM is a wasteful mistake.

THE COLLEGE

To my surprise I learnt during a conference presentation that there is such a thing as the ‘Collège Universitaire de Médecines Intégratives et Complémentaires‘ (How could I have been unaware of it all those years? Why did I never see any of their published work? Why did they never contact me and cooperate?). Its president is Prof Jacques Kopferschmitt from the University of Strasbourg, and many French Universities are members of this organisation. Here is the abstract of Kopferschmitt’s lecture on the topic of this College:

The multitude of complementary therapies or non-pharmacological interventions (NPIs) first requires pedagogical semantic harmonization to bring down the historical tensions that persist. If users often remain very or too seduced, it is not the same with health professionals! Behind the words, there are concepts that disturb because between efficiency and efficiency the nuances are subtle. However, nothing really stands in the way of modern western medicine, but there are really gaps that we could fill in the face of the growing scale of chronic diseases, the prerogative of the Western world. The need for a university investment in verification, validation and certification is essential in the face of the diversity of offers. The main beneficiaries are health professionals who need to invest in an integrative approach, particularly in France. The CUMIC promotes a different vision of efficiency and effectiveness with a broader vision of multidisciplinary evaluation, which we will discuss the main targets.

Kopferschmitt is Professor of Medical Therapy, which introduced him to a pluralism of approach to health concerns, including innovative by the introduction of the CT in the first and second cycle of medical studies. He is responsible for the teaching of Acupuncture, Auriculotherapy and hypnosis clinic. He is vice President of the Groupe d’Évaluation des Thérapies complémentaires Personnalisées (GETCOP). By founding the association of complementary Therapies at the University hospitals of Strasbourg he coordinates the introduction, teaching and research in both in Hospital and in University, who was organized many seminars on CT. He currently chairs the French University of Integrative and Complementary Medicine College (CUMIC).

This sounded odd to me; however, it got truly bizarre after I looked up what SCAM-research Kopferschmitt or any of the other officers of the College have published. I could not find a single SCAM-article authored by him/them.

DIFFERENT PLANET

Altogether I found the conference enjoyable and was pleased to meet many interesting and very kind people. But I often felt like having arrived on a different planet. Many of the discussions, lectures, ideas, comments, etc. reminded me of 1993, the year I had arrived in the UK to start our research in SCAM. What is more, I fear that French experts involved in real science might feel the same about those colleagues who seem to engage themselves in SCAM research with more enthusiasm than expertise, scientific rigour or track record. The planet I had landed on was one where critical thinking was yet to be discovered, I felt.

ADVICE

Who am I to teach others what to do?

Yes, I do hesitate to give advice – but, after all, I have researched SCAM for 25 years and published more on the subject that any researcher on the planet; and I too was once more of a SCAM-enthusiast as is apparent today. So, for what it’s worth, here is some hopefully constructive advice that crossed my mind while driving home through the beautiful French landscape:

- Sort out the confusion in terminology and define your terms as accurately as you can.

- Try to focus on the research questions that are justifiably the most important ones for improving healthcare.

- Do not attempt to re-invent the wheel.

- Once you have identified a truly relevant research question, read up what has already been published on it.

- While doing this, differentiate between rigorous research and fluff that does not meet this criterion.

- Remember to abandon your own prejudices; research is about finding the truth and not about confirming your beliefs.

- Avoid double standards like the pest.

- Publish your research in top journals and avoid SCAM-journals that nobody outside SCAM takes seriously.

- If you do not have a track record of publishing articles in top journals, please do not pretend to be an expert.

- Involve sceptics in discussions and projects.

- Remember that criticism is a precondition of progress.

I sincerely hope that this advice is not taken the wrong way. I certainly do not mean to hurt anyone’s feelings. What I do want is foremost that my French colleagues don’t have to repeat all the mistakes we did in the UK and that they are able to make swift progress.

I am being told to educate myself and rethink the subject of NAPRAPATHY by the US naprapath Dr Charles Greer. Even though he is not very polite, he just might have a point:

Edzard, enough foolish so-called scientific, educated assesments from a trained Allopathic Physician. When asked, everything that involves Alternative Medicine in your eyesight is quackery. Fortunately, every Medically trained Allopathic Physician does not have your points of view. I have partnered with Orthopaedic Surgeons, Medical Pain Specialists, General practitioners, Thoracic Surgeons, Forensic Pathologists and Others during the course, whom appreciate the Services that Naprapaths provide. Many of my current patients are Medical Physicians. Educate yourself. Visit a Naprapath to learn first hand. I expect your outlook will certainly change.

I have to say, I am not normally bowled over by anyone who calls me an ‘allopath’ (does Greer not know that Hahnemann coined this term to denigrate his opponents? Is he perhaps also in favour of homeopathy?). But, never mind, perhaps I was indeed too harsh on naprapathy in my previous post on this subject.

So, let’s try again.

Just to remind you, naprapathy was developed by the chiropractor Oakley Smith who had graduated under D D Palmer in 1899. Smith was a former Iowa medical student who also had investigated Andrew Still’s osteopathy in Kirksville, before going to Palmer in Davenport. Eventually, Smith came to reject Palmer’s concept of vertebral subluxation and developed his own concept of “the connective tissue doctrine” or naprapathy.

Dr Geer published a short article explaining the nature of naprapathy:

Naprapathy- A scientific, Evidence based, integrative, Alternative form of Pain management and nutritional assessment that involves evaluation and treatment of Connective tissue abnormalities manifested in the entire human structure. This form of Therapeutic Regimen is unique specifically to the Naprapathic Profession. Doctors of Naprapathy, pronounced ( nuh-prop-a-thee) also referred to as Naprapaths or Neuromyologists, focus on the study of connective tissue and the negative factors affecting normal tissue. These factors may begin from external sources and latently produce cellular changes that in turn manifest themselves into structural impairments, such as irregular nerve function and muscular contractures, pulling its’ bony attachments out of proper alignment producing nerve irritability and impaired lymphatic drainage. These abnormalities will certainly produce a pain response as well as swelling and tissue congestion. Naprapaths, using their hands, are trained to evaluate tissue tension findings and formulate a very specific treatment regimen which produces positive results as may be evidenced in the patients we serve. Naprapaths also rely on information obtained from observation, hands on physical examination, soft tissue Palpatory assessment, orthopedic evaluation, neurological assessment linked with specific bony directional findings, blood and urinalysis laboratory findings, diet/ Nutritional assessment, Radiology test findings, and other pertinent clinical data whose information is scrutinized and developed into a individualized and specific treatment plan. The diagnostic findings and results produced reveal consistent facts and are totally irrefutable. The deductions that formulated these concepts of theory of Naprapathic Medicine are rationally believable, and have never suffered scientific contradiction. Discover Naprapathic Medicine, it works.

What interests me most here is that naprapathy is evidence-based. Did I perhaps miss something? As I cannot totally exclude this possibility, I did another Medline search. I found several trials:

1st study (2007)

Four hundred and nine patients with pain and disability in the back or neck lasting for at least 2 weeks, recruited at 2 large public companies in Sweden in 2005, were included in this randomized controlled trial. The 2 interventions were naprapathy, including spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage, and stretching (Index Group) and support and advice to stay active and how to cope with pain, according to the best scientific evidence available, provided by a physician (Control Group). Pain, disability, and perceived recovery were measured by questionnaires at baseline and after 3, 7, and 12 weeks.

RESULTS:

At 7-week and 12-week follow-ups, statistically significant differences between the groups were found in all outcomes favoring the Index Group. At 12-week follow-up, a higher proportion in the naprapathy group had improved regarding pain [risk difference (RD)=27%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 17-37], disability (RD=18%, 95% CI: 7-28), and perceived recovery (RD=44%, 95% CI: 35-53). Separate analysis of neck pain and back pain patients showed similar results.

DISCUSSION:

This trial suggests that combined manual therapy, like naprapathy, might be an alternative to consider for back and neck pain patients.

2nd study (2010)

Subjects with non-specific pain/disability in the back and/or neck lasting for at least two weeks (n = 409), recruited at public companies in Sweden, were included in this pragmatic randomized controlled trial. The two interventions compared were naprapathic manual therapy such as spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage and stretching, (Index Group), and advice to stay active and on how to cope with pain, provided by a physician (Control Group). Pain intensity, disability and health status were measured by questionnaires.

RESULTS:

89% completed the 26-week follow-up and 85% the 52-week follow-up. A higher proportion in the Index Group had a clinically important decrease in pain (risk difference (RD) = 21%, 95% CI: 10-30) and disability (RD = 11%, 95% CI: 4-22) at 26-week, as well as at 52-week follow-ups (pain: RD = 17%, 95% CI: 7-27 and disability: RD = 17%, 95% CI: 5-28). The differences between the groups in pain and disability considered over one year were statistically significant favoring naprapathy (p < or = 0.005). There were also significant differences in improvement in bodily pain and social function (subscales of SF-36 health status) favoring the Index Group.

CONCLUSIONS:

Combined manual therapy, like naprapathy, is effective in the short and in the long term, and might be considered for patients with non-specific back and/or neck pain.

3rd study (2016)

Participants were recruited among patients, ages 18-65, seeking care at the educational clinic of Naprapathögskolan – the Scandinavian College of Naprapathic Manual Medicine in Stockholm. The patients (n = 1057) were randomized to one of three treatment arms a) manual therapy (i.e. spinal manipulation, spinal mobilization, stretching and massage), b) manual therapy excluding spinal manipulation and c) manual therapy excluding stretching. The primary outcomes were minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity and pain related disability. Treatments were provided by naprapath students in the seventh semester of eight total semesters. Generalized estimating equations and logistic regression were used to examine the association between the treatments and the outcomes.

RESULTS:

At 12 weeks follow-up, 64% had a minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity and 42% in pain related disability. The corresponding chances to be improved at the 52 weeks follow-up were 58% and 40% respectively. No systematic differences in effect when excluding spinal manipulation and stretching respectively from the treatment were found over 1 year follow-up, concerning minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity (p = 0.41) and pain related disability (p = 0.85) and perceived recovery (p = 0.98). Neither were there disparities in effect when male and female patients were analyzed separately.

CONCLUSION:

The effect of manual therapy for male and female patients seeking care for neck and/or back pain at an educational clinic is similar regardless if spinal manipulation or if stretching is excluded from the treatment option.

_________________________________________________________________

I don’t know about you, but I don’t call this ‘evidence-based’ – especially as all the three trials come from the same research group (no, not Greer; he seems to have not published at all on naprapathy). Dr Greer does clearly not agree with my assessment; on his website, he advertises treating the following conditions:

Anxiety

Back Disorders

Back Pain

Cervical Radiculopathy

Cervical Spondylolisthesis

Cervical Sprain

Cervicogenic Headache

Chronic Headache

Chronic Neck Pain

Cluster Headache

Cough Headache

Depressive Disorders

Fibromyalgia

Headache

Hip Arthritis

Hip Injury

Hip Muscle Strain

Hip Pain

Hip Sprain

Joint Clicking

Joint Pain

Joint Stiffness

Joint Swelling

Knee Injuries

Knee Ligament Injuries

Knee Sprain

Knee Tendinitis

Lower Back Injuries

Lumbar Herniated Disc

Lumbar Radiculopathy

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar Sprain

Muscle Diseases

Musculoskeletal Pain

Neck Pain

Sciatica (Not Due to Disc Displacement)

Sciatica (Not Due to Disc Displacement)

Shoulder Disorders

Shoulder Injuries

Shoulder Pain

Sports Injuries

Sports Injuries of the Knee

Stress

Tendonitis

Tennis Elbow (Lateral Epicondylitis)

Thoracic Disc Disorders

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Toe Injuries

Odd, I’d say! Did all this change my mind about naprapathy? Not really.

But nobody – except perhaps Dr Greer – can say I did not try.

And what light does this throw on Dr Greer and his professionalism? Since he seems to be already quite mad at me, I better let you answer this question.

Dengue is a viral infection spread by mosquitoes; it is common in many parts of the world. The symptoms include fever, headache, muscle/joint pain and a red rash. The infection is usually mild and lasts about a week. In rare cases it can be more serious and even life threatening. There’s no specific treatment – except for homeopathy; at least this is what many homeopaths want us to believe.

This article reports the clinical outcomes of integrative homeopathic care in a hospital setting during a severe outbreak of dengue in New Delhi, India, during the period September to December 2015.

Based on preference, 138 patients received a homeopathic medicine along with usual care (H+UC), and 145 patients received usual care (UC) alone. Assessment of thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000/mm3) was the main outcome measure. Kaplan-Meier analysis enabled comparison of the time taken to reach a platelet count of 100,000/mm3.

The results show a statistically significantly greater rise in platelet count on day 1 of follow-up in the H+UC group compared with UC alone. This trend persisted until day 5. The time taken to reach a platelet count of 100,000/mm3 was nearly 2 days earlier in the H+UC group compared with UC alone.

The authors concluded that these results suggest a positive role of adjuvant homeopathy in thrombocytopenia due to dengue. Randomized controlled trials may be conducted to obtain more insight into the comparative effectiveness of this integrative approach.

The design of the study is not able to control for placebo effects. Therefore, the question raised by this study is the following: can an objective parameter like the platelet count be influenced by placebo? The answer is clearly YES.

Why do researchers go to the trouble of conducting such a trial, while omitting both randomisation as well as placebo control? Without such design features the study lacks rigour and its results become meaningless? Why can researchers of Dengue fever run a trial without reporting symptomatic improvements? Could the answer to these questions perhaps be found in the fact that the authors are affiliated to the ‘Central Council for Research in Homoeopathy, New Delhi?

One could argue that this trial – yet another one published in the journal ‘Homeopathy’ – is a waste of resources and patients’ co-operation. Therefore, one might even argue, such a study might be seen as unethical. In any case, I would argue that this study is irrelevant nonsense that should have never seen the light of day.

As you can imagine, I get quite a lot of ‘fan-post’. Most of the correspondence amounts to personal attacks and insults which I usually discard. But some of these ‘love-letters’ are so remarkable in one way or another that I answer them. This short email was received on 20/3/19; it belongs to the latter category:

Dr Ernst,

You have been trashing homeopathy ad nauseum for so many years based on your limited understanding of it. You seem to know little more than that the remedies are so extremely dilute as to be impossibly effective in your opinion. Everybody knows this and has to confront their initial disbelief.

Why dont you get some direct understanding of homeopathy by doing a homeopathic proving of an unknown (to you) remedy? Only once was I able to convince a skeptic to take the challenge to do a homeopathic proving. He was amazed at all the new symptoms he experienced after taking the remedy repeatedly over several days.

Please have a similar bravery in your approach to homeopathy instead of basing your thoughts purely on your speculation on the subject, grounded in little understanding and no experience of it.

THIS IS HOW I RESPONDED

Dear Mr …

thank you for this email which I would like to answer as follows.

Your lines give the impression that you might not be familiar with the concept of critical analysis. In fact, you seem to confuse my criticism of homeopathy with ‘trashing it’. I strongly recommend you read up about critical analysis. No doubt you will then realise that it is a necessary and valuable process towards generating progress in healthcare and beyond.

You assume that I have limited understanding of homeopathy. In fact, I grew up with homeopathy, practised homeopathy as a young doctor, researched the subject for more than 25 years and published several books as well as over 100 peer-reviewed scientific papers about it. All of this, I have disclosed publicly, for instance, in my memoir which might interest you.

The challenge you mention has been taken by me and others many times. It cannot convince critical thinkers and, frankly, I am surprised that you found a sceptic who was convinced by what essentially amounts to little more than a party trick. But, as you seem to like challenges, I invite you to consider taking the challenge of the INH which even offers a sizable amount of money, in case you are successful.

Your final claim that my thoughts are based purely on speculation is almost farcically wrong. The truth is that sceptics try their very best to counter-balance the mostly weird speculations of homeopaths with scientific facts. I am sure that, once you have acquired the skills of critical thinking, you will do the same.

Best of luck.

Edzard Ernst

An impressive 17% of US chiropractic patients are 17 years of age or younger. This figure increases to 39% among US chiropractors who have specialized in paediatrics. Data for other countries can be assumed to be similar. But is chiropractic effective for children? All previous reviews concluded that there is a paucity of evidence for the effectiveness of manual therapy for conditions within paediatric populations.

This systematic review is an attempt to shed more light on the issue by evaluating the use of manual therapy for clinical conditions in the paediatric population, assessing the methodological quality of the studies found, and synthesizing findings based on health condition.

Of the 3563 articles identified through various literature searches, 165 full articles were screened, and 50 studies (32 RCTs and 18 observational studies) met the inclusion criteria. Only 18 studies were judged to be of high quality. Conditions evaluated were:

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

- autism,

- asthma,

- cerebral palsy,

- clubfoot,

- constipation,

- cranial asymmetry,

- cuboid syndrome,

- headache,

- infantile colic,

- low back pain,

- obstructive apnoea,

- otitis media,

- paediatric dysfunctional voiding,

- paediatric nocturnal enuresis,

- postural asymmetry,

- preterm infants,

- pulled elbow,

- suboptimal infant breastfeeding,

- scoliosis,

- suboptimal infant breastfeeding,

- temporomandibular dysfunction,

- torticollis,

- upper cervical dysfunction.

Musculoskeletal conditions, including low back pain and headache, were evaluated in seven studies. Only 20 studies reported adverse events.

The authors concluded that fifty studies investigated the clinical effects of manual therapies for a wide variety of pediatric conditions. Moderate-positive overall assessment was found for 3 conditions: low back pain, pulled elbow, and premature infants. Inconclusive unfavorable outcomes were found for 2 conditions: scoliosis (OMT) and torticollis (MT). All other condition’s overall assessments were either inconclusive favorable or unclear. Adverse events were uncommonly reported. More robust clinical trials in this area of healthcare are needed.

There are many things that I find remarkable about this review:

- The list of indications for which studies have been published confirms the notion that manual therapists – especially chiropractors – regard their approach as a panacea.

- A systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of a therapy that includes observational studies without a control group is, in my view, highly suspect.

- Many of the RCTs included in the review are meaningless; for instance, if a trial compares the effectiveness of two different manual therapies none of which has been shown to work, it cannot generate a meaningful result.

- Again, we find that the majority of trialists fail to report adverse effects. This is unethical to a degree that I lose faith in such studies altogether.

- Only three conditions are, according to the authors, based on evidence. This is hardly enough to sustain an entire speciality of paediatric chiropractors.

Allow me to have a closer look at these three conditions.

- Low back pain: the verdict ‘moderate positive’ is based on two RCTs and two observational studies. The latter are irrelevant for evaluating the effectiveness of a therapy. One of the two RCTs should have been excluded because the age of the patients exceeded the age range named by the authors as an inclusion criterion. This leaves us with one single ‘medium quality’ RCT that included a mere 35 patients. In my view, it would be foolish to base a positive verdict on such evidence.

- Pulled elbow: here the verdict is based on one RCT that compared two different approaches of unknown value. In my view, it would be foolish to base a positive verdict on such evidence.

- Preterm: Here we have 4 RCTs; one was a mere pilot study of craniosacral therapy following the infamous A+B vs B design. The other three RCTs were all from the same Italian research group; their findings have never been independently replicated. In my view, it would be foolish to base a positive verdict on such evidence.

So, what can be concluded from this?

I would say that there is no good evidence for chiropractic, osteopathic or other manual treatments for children suffering from any condition.

And why do the authors of this new review arrive at such dramatically different conclusion? I am not sure. Could it perhaps have something to do with their affiliations?

- Palmer College of Chiropractic,

- Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

- Performance Chiropractic.

What do you think?

A new update of the current Cochrane review assessed the benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for the treatment of chronic low back pain. The authors included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effect of spinal manipulation or mobilisation in adults (≥18 years) with chronic low back pain with or without referred pain. Studies that exclusively examined sciatica were excluded.

The effect of SMT was compared with recommended therapies, non-recommended therapies, sham (placebo) SMT, and SMT as an adjuvant therapy. Main outcomes were pain and back specific functional status, examined as mean differences and standardised mean differences (SMD), respectively. Outcomes were examined at 1, 6, and 12 months.

Forty-seven RCTs including a total of 9211 participants were identified. Most trials compared SMT with recommended therapies. In 16 RCTs, the therapists were chiropractors, in 14 they were physiotherapists, and in 5 they were osteopaths. They used high velocity manipulations in 18 RCTs, low velocity manipulations in 12 studies and a combination of the two in 20 trials.

Moderate quality evidence suggested that SMT has similar effects to other recommended therapies for short term pain relief and a small, clinically better improvement in function. High quality evidence suggested that, compared with non-recommended therapies, SMT results in small, not clinically better effects for short term pain relief and small to moderate clinically better improvement in function.

In general, these results were similar for the intermediate and long term outcomes as were the effects of SMT as an adjuvant therapy.

Low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months. Low quality evidence suggested that SMT results in a moderate to strong statistically significant and clinically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically significant better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months.

(Mean difference in reduction of pain at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months (0-100; 0=no pain, 100 maximum pain) for spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) versus recommended therapies in review of the effects of SMT for chronic low back pain. Pooled mean differences calculated by DerSimonian-Laird random effects model.)

About half of the studies examined adverse and serious adverse events, but in most of these it was unclear how and whether these events were registered systematically. Most of the observed adverse events were musculoskeletal related, transient in nature, and of mild to moderate severity. One study with a low risk of selection bias and powered to examine risk (n=183) found no increased risk of an adverse event or duration of the event compared with sham SMT. In one study, the Data Safety Monitoring Board judged one serious adverse event to be possibly related to SMT.

The authors concluded that SMT produces similar effects to recommended therapies for chronic low back pain, whereas SMT seems to be better than non-recommended interventions for improvement in function in the short term. Clinicians should inform their patients of the potential risks of adverse events associated with SMT.

This paper is currently being celebrated (mostly) by chiropractors who think that it vindicates their treatments as being both effective and safe. However, I am not sure that this is entirely true. Here are a few reasons for my scepticism:

- SMT is as good as other recommended treatments for back problems – this may be so but, as no good treatment for back pain has yet been found, this really means is that SMT is as BAD as other recommended therapies.

- If we have a handful of equally good/bad treatments, it stand to reason that we must use other criteria to identify the one that is best suited – criteria like safety and cost. If we do that, it becomes very clear that SMT cannot be named as the treatment of choice.

- Less than half the RCTs reported adverse effects. This means that these studies were violating ethical standards of publication. I do not see how we can trust such deeply flawed trials.

- Any adverse effects of SMT were minor, restricted to the short term and mainly centred on musculoskeletal effects such as soreness and stiffness – this is how some naïve chiro-promoters already comment on the findings of this review. In view of the fact that more than half the studies ‘forgot’ to report adverse events and that two serious adverse events did occur, this is a misleading and potentially dangerous statement and a good example how, in the world of chiropractic, research is often mistaken for marketing.

- Less than half of the studies (45% (n=21/47)) used both an adequate sequence generation and an adequate allocation procedure.

- Only 5 studies (10% (n=5/47)) attempted to blind patients to the assigned intervention by providing a sham treatment, while in one study it was unclear.

- Only about half of the studies (57% (n=27/47)) provided an adequate overview of withdrawals or drop-outs and kept these to a minimum.

- Crucially, this review produced no good evidence to show that SMT has effects beyond placebo. This means the modest effects emerging from some trials can be explained by being due to placebo.

- The lead author of this review (SMR), a chiropractor, does not seem to be free of important conflicts of interest: SMR received personal grants from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), the European Centre for Chiropractic Research Excellence (ECCRE), the Belgian Chiropractic Association (BVC) and the Netherlands Chiropractic Association (NCA) for his position at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He also received funding for a research project on chiropractic care for the elderly from the European Centre for Chiropractic Research and Excellence (ECCRE).

- The second author (AdeZ) who also is a chiropractor received a grant from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), for an independent study on the effects of SMT.

After carefully considering the new review, my conclusion is the same as stated often before: SMT is not supported by convincing evidence for back (or other) problems and does not qualify as the treatment of choice.

A recent blog-post pointed out that the usefulness of yoga in primary care is doubtful. Now we have new data to shed some light on this issue.

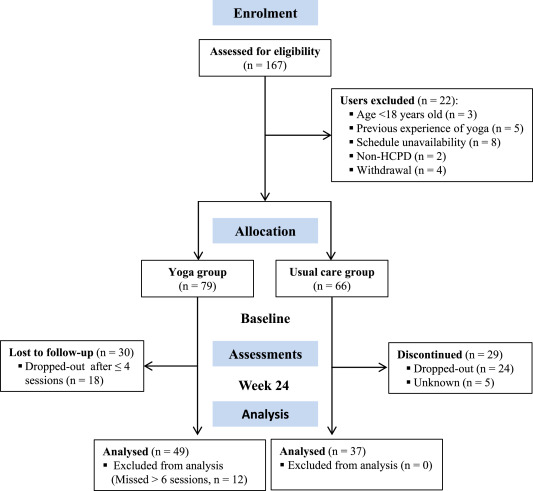

The new paper reports a ‘prospective, longitudinal, quasi-experimental study‘. Yoga group (n= 49) underwent 24-weeks program of one-hour yoga sessions. The control group had no yoga.

Participation was voluntary and the enrolment strategy was based on invitations by health professionals and advertising in the community (e.g., local newspaper, health unit website and posters). Users willing to participate were invited to complete a registration form to verify eligibility criteria.

The endpoints of the study were:

- quality of life,

- psychological distress,

- satisfaction level,

- adherence rate.

The yoga routine consisted of breathing exercises, progressive articular and myofascial warming-up, followed by surya namascar (sun salutation sequence; adapted to the physical condition of each participant), alignment exercises, and postural awareness. Practice also included soft twists of the spine, reversed and balance postures, as well as concentration exercises. During the sessions, the instructor discussed some ethical guidelines of yoga, as for example, non-violence (ahimsa) and truthfulness (satya), to allow the participant to have a safer and integrated practice. In addition, the participants were encouraged to develop their awareness of the present moment and their body sensations, through a continuous process of self-consciousness, keeping a distance between body sensations and the emotional experience. The instructor emphasized the connection between breathing and movement. Each session ended with a guided deep relaxation (yoga nidra; 5–10 min), followed by a meditation practice (5–10 min).

The results of the study showed that the patients in the yoga group experienced a significant improvement in all domains of quality of life and a reduction of psychological distress. Linear regression analysis showed that yoga significantly improved psychological quality of life.

The authors concluded that yoga in primary care is feasible, safe and has a satisfactory adherence, as well as a positive effect on psychological quality of life of participants.

Are the authors’ conclusions correct?

I think not!

Here are some reasons for my judgement:

- The study was far to small to justify far-reaching conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of yoga.

- There were relatively high numbers of drop-outs, as seen in the graph above. Despite this fact, no intention to treat analysis was used.

- There was no randomisation, and therefore the two groups were probably not comparable.

- Participants of the experimental group chose to have yoga; their expectations thus influenced the outcomes.

- There was no attempt to control for placebo effects.

- The conclusion that yoga is safe would require a sample size that is several dimensions larger than 49.

In conclusion, this study fails to show that yoga has any value in primary care.

PS

Oh, I almost forgot: and yoga is also satanic, of course (just like reading Harry Potter!).