TCM

On this blog, we have seen more than enough evidence of how some proponents of alternative medicine can react when they feel cornered by critics. They often direct vitriol in their direction. Ad hominem attacks are far from being rarities. A more forceful option is to sue them for libel. In my own case, Prince Charles went one decisive step further and made sure that my entire department was closed down. In China, they have recently and dramatically gone even further.

This article in Nature tells the full story:

A Chinese doctor who was arrested after he criticized a best-selling traditional Chinese remedy has been released, after more than three months in detention. Tan Qindong had been held at the Liangcheng county detention centre since January, when police said a post Tan had made on social media damaged the reputation of the traditional medicine and the company that makes it.

On 17 April, a provincial court found the police evidence for the case insufficient. Tan, a former anaesthesiologist who has founded several biomedical companies, was released on bail on that day. Tan, who lives in Guangzhou in southern China, is now awaiting trial. Lawyers familiar with Chinese criminal law told Nature that police have a year to collect more evidence or the case will be dismissed. They say the trial is unlikely to go ahead…

The episode highlights the sensitivities over traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) in China. Although most of these therapies have not been tested for efficacy in randomized clinical trials — and serious side effects have been reported in some1 — TCM has support from the highest levels of government. Criticism of remedies is often blocked on the Internet in China. Some lawyers and physicians worry that Tan’s arrest will make people even more hesitant to criticize traditional therapies…

Tan’s post about a medicine called Hongmao liquor was published on the Chinese social-media app Meipian on 19 December…Three days later, the liquor’s maker, Hongmao Pharmaceuticals in Liangcheng county of Inner Mongolia autonomous region, told local police that Tan had defamed the company. Liangcheng police hired an accountant who estimated that the damage to the company’s reputation was 1.4 million Chinese yuan (US$220,000), according to official state media, the Beijing Youth Daily. In January, Liangcheng police travelled to Guangzhou to arrest Tan and escort him back to Liangcheng, according to a police statement.

Sales of Hongmao liquor reached 1.63 billion yuan in 2016, making it the second best-selling TCM in China that year. It was approved to be sold by licensed TCM shops and physicians in 1992 and approved for sale over the counter in 2003. Hongmao Pharmaceuticals says that the liquor can treat dozens of different disorders, including problems with the spleen, stomach and kidney, as well as backaches…

Hongmao Pharmaceuticals did not respond to Nature’s request for an interview. However, Wang Shengwang, general manager of the production center of Hongmao Liquor, and Han Jun, assistant to the general manager, gave an interview to The Paper on 16 April. The pair said the company did not need not publicize clinical trial data because Hongmao liquor is a “protected TCM composition”. Wang denied allegations in Chinese media that the company pressured the police to pursue Tan or that it dispatched staff to accompany the police…

Xia is worried that the case could further silence public criticism of TCMs, environmental degredation, and other fields where comment from experts is crucial. The Tan arrest “could cause fear among scientists” and dissuade them from posting scientific comments, he says.

END OF QUOTE

On this blog, we have repeatedly discussed concerns over the validity of TCM data/material that comes out of China (see for instance here, here and here). This chilling case, I am afraid, is not prone to increase our confidence.

Prof Ke’s Asante Academy (Ke claims that asante is French and means good health – wrong, of course, but that’s the least of his errors) offers many amazing things, and I do encourage you to have a look at his website. Prof Ke is clearly not plagued by false modesty; he informs us that “I am proud to say that we have gained a reputation as one of the leading Chinese Medicine clinics and teaching institutes in the UK and Europe. One CEO from a leading Acupuncture register commented that we were the best in the country. One doctor gave up his medical job in a European country to come study Chinese medicine at Middlesex University (our partner) – he said simply it was because of Asante. Our patients, from royalty and celebrities to hard working people all over the world, have praised us highly for successfully treating their wide-ranging conditions, including infertility, skin problems, pain and many others. We are also very pleased to have pioneered Acupuncture service in the NHS and for over a decade we have seen tens of thousands of NHS patients in hospitals.”

He provides treatments for any condition you can imagine, courses in various forms of TCM, a range of videos (they are particularly informative), as well as interesting explanations and treatment plans for dozens of conditions. From the latter, I have chosen just two diseases and quote some extracts to give you a vivid impression of the Ke’s genius:

CANCER

There are some ways in which Chinese medicine can help cancer cases where Western medicine cannot. Various herbal prescriptions have been shown to help in bolstering the immune system and some herbs can actually attack the abnormal cells and viruses which are responsible for certain types of cancer.

Chinese Medicine treatment aims first to increase the body’s own defence mechanisms, then to kill the cancer cells. Effective though radiotherapy and chemotherapy may be, they tend to have a drastic effect on the body generally and patients often feel very tired and weak, suffer from stress, anxiety, fear, insomnia and loss of appetite. Chinese Medicine practitioners regard strengthening the patient psychologically and physically to be of primary importance.

Chinese Medicine herbal remedies can help reduce or eliminate the side-effects from radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Astragalus will help raise the blood cell count, the sickness caused by chemotherapy can be relieved with fresh ginger and orange peel, and acupuncture can also help. To attack the cancer itself, depending on type and location, different herbs will be used.

A Chinese Medicine practitiioner will decide whether the illness is the result of qi energy deficiency, blood deficiency or yin or yang deficiency. Ginseng,astragalus, Chinese angelica, cooked rehmannia root, wolfberry root, Chinese yam and many tonic herbs may be used. But it is vital to remember that no one tonic is good for everybody. All treatments are dependent upon the individual. Some anti-cancer herbs used are very strong and sometimes make people sick, but this is because one poison is being used against another. How they work, and how clinically effective they are, is still being researched. No claims can be made for them based on modern scientific evaluation.

Acupuncture and meditation are also very important parts of the Chinese Medicine traditional approach to the treatment of cancer. These alleviate pain and induce a sense of calmness, instill confidence and build up the spirit of the body, so that patients do not need to take so many painkillers. In China, they have many meditation programmes which are used to treat cancer.

MENINGITIS

Chinese Medicine herbal treatment for meningitis has been very successful in China. In the recent past there were many epidemics, particularly in the north, and the hospitals routinely used Chinese herbs as treatment, with a high degree of success. One famous remedy in Chinese Medicine is called White Tiger Decoction, the main ingredients of which are gypsum and rice. These are simple things but they reduce the high fever and clear the infection from the brain. Modern medicine and Chinese Medicine used together is the most effective treatment.

END OF QUOTES

Ghosh, I am so glad that finally someone explained these things to me, and so logically and simply too. I used to have doubts about the value of TCM for these conditions, but now I am convinced … so much so that I go on Medline to find the scientific work of Prof Ke. But what, what, what? That is not possible; such a famous professor and no publications?

I conclude that my search skills are inadequate and throw myself into studying the plethora of courses Ke offers for the benefit of mankind:

Since 2000, Asanté Academy has officially collaborated with Middlesex University in running and teaching the BSc and MSc in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

- BSc Degrees in Acupuncture and Traditional Chinese Medicine

- MSc Degree in Chinese Medicine

- Professional Practice in Herbal Medicine, Chinese Herbal Medicine and Acupuncture

But perhaps this is a bit too arduous; maybe so-called diploma courses suit me better? Personally, I am tempted by the ‘24-day Certificate Course in TCM Acupuncture‘ – it’s a bargain, just £ 2,880!

PS

Prof Ke, if you read these lines, would you please tell us where and when you got your professorship? Your otherwise ostentatious website seems to fail to disclose this detail.

The plethora of dodgy meta-analyses in alternative medicine has been the subject of a recent post – so this one is a mere update of a regular lament.

This new meta-analysis was to evaluate evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation (LDH). (Call me pedantic, but I prefer meta-analyses that evaluate the evidence FOR AND AGAINST a therapy.) Electronic databases were searched to identify RCTs of acupuncture for LDH, and 30 RCTs involving 3503 participants were included; 29 were published in Chinese and one in English, and all trialists were Chinese.

The results showed that acupuncture had a higher total effective rate than lumbar traction, ibuprofen, diclofenac sodium and meloxicam. Acupuncture was also superior to lumbar traction and diclofenac sodium in terms of pain measured with visual analogue scales (VAS). The total effective rate in 5 trials was greater for acupuncture than for mannitol plus dexamethasone and mecobalamin, ibuprofen plus fugui gutong capsule, loxoprofen, mannitol plus dexamethasone and huoxue zhitong decoction, respectively. Two trials showed a superior effect of acupuncture in VAS scores compared with ibuprofen or mannitol plus dexamethasone, respectively.

The authors from the College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, concluded that acupuncture showed a more favourable effect in the treatment of LDH than lumbar traction, ibuprofen, diclofenac sodium, meloxicam, mannitol plus dexamethasone and mecobalamin, fugui gutong capsule plus ibuprofen, mannitol plus dexamethasone, loxoprofen and huoxue zhitong decoction. However, further rigorously designed, large-scale RCTs are needed to confirm these findings.

Why do I call this meta-analysis ‘dodgy’? I have several reasons, 10 to be exact:

- There is no plausible mechanism by which acupuncture might cure LDH.

- The types of acupuncture used in these trials was far from uniform and included manual acupuncture (MA) in 13 studies, electro-acupuncture (EA) in 10 studies, and warm needle acupuncture (WNA) in 7 studies. Arguably, these are different interventions that cannot be lumped together.

- The trials were mostly of very poor quality, as depicted in the table above. For instance, 18 studies failed to mention the methods used for randomisation. I have previously shown that some Chinese studies use the terms ‘randomisation’ and ‘RCT’ even in the absence of a control group.

- None of the trials made any attempt to control for placebo effects.

- None of the trials were conducted against sham acupuncture.

- Only 10 studies 10 trials reported dropouts or withdrawals.

- Only two trials reported adverse reactions.

- None of these shortcomings were critically discussed in the paper.

- Despite their affiliation, the authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

- All trials were conducted in China, and, on this blog, we have discussed repeatedly that acupuncture trials from China never report negative results.

And why do I find the journal ‘dodgy’?

Because any journal that publishes such a paper is likely to be sub-standard. In the case of ‘Acupuncture in Medicine’, the official journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society, I see such appalling articles published far too frequently to believe that the present paper is just a regrettable, one-off mistake. What makes this issue particularly embarrassing is, of course, the fact that the journal belongs to the BMJ group.

… but we never really thought that science publishing was about anything other than money, did we?

What an odd title, you might think.

Systematic reviews are the most reliable evidence we presently have!

Yes, this is my often-voiced and honestly-held opinion but, like any other type of research, systematic reviews can be badly abused; and when this happens, they can seriously mislead us.

A new paper by someone who knows more about these issues than most of us, John Ioannidis from Stanford university, should make us think. It aimed at exploring the growth of published systematic reviews and meta‐analyses and at estimating how often they are redundant, misleading, or serving conflicted interests. Ioannidis demonstrated that publication of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses has increased rapidly. In the period January 1, 1986, to December 4, 2015, PubMed tags 266,782 items as “systematic reviews” and 58,611 as “meta‐analyses.” Annual publications between 1991 and 2014 increased 2,728% for systematic reviews and 2,635% for meta‐analyses versus only 153% for all PubMed‐indexed items. Ioannidis believes that probably more systematic reviews of trials than new randomized trials are published annually. Most topics addressed by meta‐analyses of randomized trials have overlapping, redundant meta‐analyses; same‐topic meta‐analyses may exceed 20 sometimes.

Some fields produce massive numbers of meta‐analyses; for example, 185 meta‐analyses of antidepressants for depression were published between 2007 and 2014. These meta‐analyses are often produced either by industry employees or by authors with industry ties and results are aligned with sponsor interests. China has rapidly become the most prolific producer of English‐language, PubMed‐indexed meta‐analyses. The most massive presence of Chinese meta‐analyses is on genetic associations (63% of global production in 2014), where almost all results are misleading since they combine fragmented information from mostly abandoned era of candidate genes. Furthermore, many contracting companies working on evidence synthesis receive industry contracts to produce meta‐analyses, many of which probably remain unpublished. Many other meta‐analyses have serious flaws. Of the remaining, most have weak or insufficient evidence to inform decision making. Few systematic reviews and meta‐analyses are both non‐misleading and useful.

The author concluded that the production of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses has reached epidemic proportions. Possibly, the large majority of produced systematic reviews and meta‐analyses are unnecessary, misleading, and/or conflicted.

Ioannidis makes the following ‘Policy Points’:

- Currently, there is massive production of unnecessary, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Instead of promoting evidence‐based medicine and health care, these instruments often serve mostly as easily produced publishable units or marketing tools.

- Suboptimal systematic reviews and meta‐analyses can be harmful given the major prestige and influence these types of studies have acquired.

- The publication of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses should be realigned to remove biases and vested interests and to integrate them better with the primary production of evidence.

Obviously, Ioannidis did not have alternative medicine in mind when he researched and published this article. But he easily could have! Virtually everything he stated in his paper does apply to it. In some areas of alternative medicine, things are even worse than Ioannidis describes.

Take TCM, for instance. I have previously looked at some of the many systematic reviews of TCM that currently flood Medline, based on Chinese studies. This is what I concluded at the time:

Why does that sort of thing frustrate me so much? Because it is utterly meaningless and potentially harmful:

- I don’t know what treatments the authors are talking about.

- Even if I managed to dig deeper, I cannot get the information because practically all the primary studies are published in obscure journals in Chinese language.

- Even if I did read Chinese, I do not feel motivated to assess the primary studies because we know they are all of very poor quality – too flimsy to bother.

- Even if they were formally of good quality, I would have my doubts about their reliability; remember: 100% of these trials report positive findings!

- Most crucially, I am frustrated because conclusions of this nature are deeply misleading and potentially harmful. They give the impression that there might be ‘something in it’, and that it (whatever ‘it’ might be) could be well worth trying. This may give false hope to patients and can send the rest of us on a wild goose chase.

So, to ease the task of future authors of such papers, I decided give them a text for a proper EVIDENCE-BASED conclusion which they can adapt to fit every review. This will save them time and, more importantly perhaps, it will save everyone who might be tempted to read such futile articles the effort to study them in detail. Here is my suggestion for a conclusion soundly based on the evidence, not matter what TCM subject the review is about:

OUR SYSTEMATIC REVIEW HAS SHOWN THAT THERAPY ‘X’ AS A TREATMENT OF CONDITION ‘Y’ IS CURRENTLY NOT SUPPORTED BY SOUND EVIDENCE.

On another occasion, I stated that I am getting very tired of conclusions stating ‘…XY MAY BE EFFECTIVE/HELPFUL/USEFUL/WORTH A TRY…’ It is obvious that the therapy in question MAY be effective, otherwise one would surely not conduct a systematic review. If a review fails to produce good evidence, it is the authors’ ethical, moral and scientific obligation to state this clearly. If they don’t, they simply misuse science for promotion and mislead the public. Strictly speaking, this amounts to scientific misconduct.

In yet another post on the subject of systematic reviews, I wrote that if you have rubbish trials, you can produce a rubbish review and publish it in a rubbish journal (perhaps I should have added ‘rubbish researchers).

And finally this post about a systematic review of acupuncture: it is almost needless to mention that the findings (presented in a host of hardly understandable tables) suggest that acupuncture is of proven or possible effectiveness/efficacy for a very wide array of conditions. It also goes without saying that there is no critical discussion, for instance, of the fact that most of the included evidence originated from China, and that it has been shown over and over again that Chinese acupuncture research never seems to produce negative results.

The main point surely is that the problem of shoddy systematic reviews applies to a depressingly large degree to all areas of alternative medicine, and this is misleading us all.

So, what can be done about it?

My preferred (but sadly unrealistic) solution would be this:

STOP ENTHUSIASTIC AMATEURS FROM PRETENDING TO BE RESEARCHERS!

Research is not fundamentally different from other professional activities; to do it well, one needs adequate training; and doing it badly can cause untold damage.

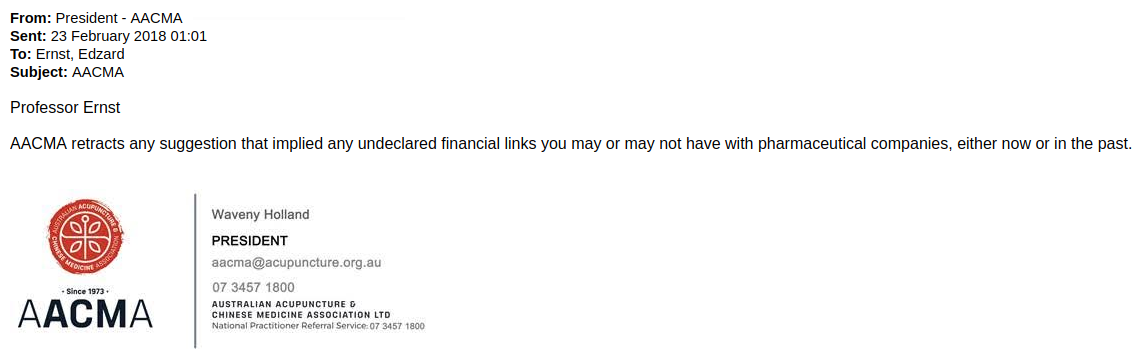

I have to admit that I had little hope it would come. But after sending my ‘open letter’ twice to their email address, I have just received this:

As you might remember, the AACMA had accused me of an pecuniary undeclared link with the pharmaceutical industry. Their claim was based on me having been the editor of a journal, FACT, which was co-published by the British Pharmaceutical Society (BPS). When I complained and the AACMA learnt that the journal had been discontinued, they retracted their claim but carried on distributing the allegation that I had formerly had an undeclared conflict of interest. When they finally understood that the BPS was not the pharmaceutical industry (all it takes is a simple Google search), and after me complaining again and again, they sent me the above email.

The full details of this sorry story are here and here.

So, the AACMA have done the right thing?

Yes and no!

The have retracted their repeated lies.

But they have not done this publicly as requested (this is partly the reason for me writing this post to make their retraction public).

More importantly, they have not apologised !!!

Why should they, you might ask.

- Because they have (tried to) damage my reputation as an independent scientist.

- Because they have not done their research before making and insisting on a far-reaching claim.

- Because they have shown themselves too stupid to grasp even the most elementary issues.

By not apologising, they have, I find, shown how unprofessional they really are, and how much they lack simple human decency. On their website, the AACMA state that “since 1973, AACMA has represented the profession and values high standards in ethical and professional practice.” Personally, I think that their standards in ethical and professional practice are appalling.

I was reliably informed that the ‘Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association’ (AACMA) are currently – that is AFTER having retracted the falsehoods they previously issued about me – distributing a document which contains the following passage:

It is noted that Mr Ernst derives income from editing a journal called Focus on Alternative and Complementary Medicine which is published by the British Pharmaceutical Society and listed in pharamcologyjournals.com. Ernst has not declared his own pecuniary conflicts of interest and links with the pharmaceutical industry. I note that the FSM webpage declares that:

‘None of the members of the executive has any vested interests in pharmaceutical companies such that our views or opinions might be influenced’.

This statement is disingenuous and deceptive if instead you base your critique on the blog of a person with such pharmaceutical interests without declaring it.

This is a repetition of the lies which the AACMA have already retracted (see comments section of my previous post on this matter). In my view, this is highly dishonest and actionable. For this reason, I today sent them this ‘open letter’ which I also publish here:

Dear Madam/Sir,

As explained more fully in this blog-post, you have recently accused me of undeclared links to and payments from the pharmaceutical industry. This is a serious, potentially liable allegation.

My objections were followed by your retraction of these allegations (see the comments section of my above-mentioned blog-post). However, your retraction displays an embarrassing level of ignorance and contains several grave errors (see the comments section of my above-mentioned blog-post). Crucially, it implies that I formerly had an undeclared conflict of interest. This is untrue. More importantly, you currently distribute a document that continues to allege that I currently have ‘pharmaceutical interests’. This too is untrue.

I urge you to either produce the evidence for your allegations, or to fully and publicly retract them. This strategy would not merely be the only decent and professional way of dealing with the problem, it also might prevent damage to your reputation, and avoid libel action against you.

Sincerely

Edzard Ernst

Difficulties breastfeeding?

Some say that Chinese herbal medicine offers a solution.

This Chinese multi-centre RCT included 588 mothers considering breastfeeding. The intervention group received the Chinese herbal mixture Zengru Gao, while the control group received no therapy. The primary outcomes were the percentages of fully and partially breastfeeding mothers, and a secondary outcome was baby’s daily formula intake.

At day 3 and 7 after delivery, significant differences were found in favour of Zengru Gao group on the percentage of full/ partial breastfeeding. At day 7, the percentage of full/ partial breastfeeding of the active group increased to 71.48%/20.70% versus 58.67%/30.26% in the control group, the differences remained significant. No statistically significant differences were detected on primary measures at day. While intake of formula differed between groups at day 1 and 3, this difference did not achieve statistical significance, but this difference was apparent by day 7.

The authors concluded that the Chinese Herbal medicine Zengru Gao enhanced breastfeeding success during one week postpartum. The approach is acceptable to participants and merits further evaluation.

To the naïve observer, this study might look rigorous, but it is a seriously flawed RCT. Here are just some of its most obvious limitations:

- All we get in the methods section is this explanation: Participants were randomly allocated to the blank control group or the intervention group: Zengru Gao, orally, 30 g a time and 3 times a day. This seems to indicate that the control group got no treatment at all which means there was no blinding nor placebo control. The authors even comment on this point in the discussion section of their paper stating that because we included new mothers who received no treatment as a control group, we were able to prove that the improvement in breastfeeding was not due to the placebo effect. However, this is a totally nonsensical argument.

- The experimental treatment is not reproducible. The authors state: Zengru Gao, a Chinese herbal formula, which is composed of 8 herbs: Semen Vaccariae, Medulla Tetrapanacis, Radix Rehmanniae Praeparata, Radix Angelicae Sinensis, Radix Paeoniae Alba,Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Herba Leonuri, Radix Trichosanthis. This is not enough information to replicate the study outside China where the mixture is not commercially available.

- The primary outcome was the percentage of fully, and partially breastfeeding mothers. Breastfeeding was defined as mother’s milk given by direct breast feeding. Full breastfeeding meant that no other types of milk or solids were given. Partially breastfeeding meant that sustained latch with deep rhythmic sucking through the length of the feed, with some pause, on either/ or both breasts. We are not being told how the endpoint was quantified. Presumably women kept diaries. We cannot guess how accurate this process was.

- As far as I can see, there was no correction for multiple testing for statistical significance. This means that some or all of the significant results might be false-positive.

- There is insufficient data to show that the herbal mixture is safe for the mothers and the babies. At the very minimum, the researchers should have measured essential safety parameters. This omission is a gross violation of research ethics.

- Towards the end of the paper, we find the following statement: The authors would like to thank the Research and Development Department of Zhangzhou Pien Tze Huang Pharmaceutical co., Ltd. … The authors declare that they have no competing interests. And the 1st and 3rd authors are “affiliated with” Guangzhou Hipower Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China, i. e. work for the manufacturer of the mixture. This does clearly not make any sense whatsoever.

I have seen too many flawed studies of alternative medicine to be shocked or even surprised by this level of incompetence and nonsense. Yet, I still find it lamentable. But, in my view, the worst is that supposedly peer-reviewed journals such as ‘BMC Complement Altern Med’ publish such overt rubbish.

It would be easy to shrug one’s shoulder and bin the paper. But the effect of such fatally flawed research is too serious for that. In our recent book MORE HARM THAN GOOD? THE MORAL MAZE OF COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE, we discuss that such flawed science amounts to a violation of medical ethics: CAM journals allocate peer review tasks to a narrow range of CAM enthusiasts who often have been chosen by the authors of the article in question. The raison d’être of CAM journals and CAM researchers is inextricably tied to a belief in CAM, resulting in a self-referential situation which is permissive to the acceptance of weak or flawed reports of clinical effectiveness… Defective research—whether at the design, execution, analysis, or reporting stage—corrupts the repository of reliable medical knowledge. Ultimately, this leads to suboptimal and erroneous treatment decisions…

The Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association Ltd (AACMA) is the “peak professional body of qualified acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine practitioners in Australia. AACMA has represented the profession since 1973 and values high standards in ethical and professional practice.”

High standards in ethical and professional practice?

Really?

Somehow, I doubt it!

Why?

Because they recently wrote to ‘Friends of Science in Medicine‘ categorically stating that I have “undeclared links to the pharmaceutical industry”.

To set the record straight (yet again), I here provide a complete list of all my links to the pharmaceutical industry, plus all my sponsorships and inducements from BIG PHARMA and elsewhere :

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

END OF LIST

As erring is human but lying is unethical, I herewith want to give the The Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association an opportunity to withdraw their statement and post an apology. To make sure they know about this invitation, I have sent them this blog via an email. Failing an apology I might take appropriate action and I will certainly declare the association to be neither professional nor ethical.

I am waiting – shall we say until one week from today?

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is popular, not least because it is heavily marketed and thus often perceived as natural and safe. But is this assumption true?

This study analysed liver tests before and following treatment with herbal Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in order to evaluate the risk of liver injury. Patients with normal values of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as a diagnostic marker for ruling out pre-existing liver disease were enrolled in a prospective study of a safety program carried out at the First German Hospital of TCM from 1994 to 2015. All patients received herbal products, and their ALT values were reassessed 1-3 d prior to discharge. To evaluate causality for suspected TCM herbs, the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) was used.

The report presents data of 21470 patients. ALT ranged from 1 × to < 5 × upper limit normal (ULN) in 844 patients (3.93%) and suggested mild or moderate liver adaptive abnormalities. A total of 26 patients (0.12%) experienced higher ALT values of ≥ 5 × ULN (300.0 ± 172.9 U/L, mean ± SD). Causality for TCM herbs was estimated to be probable in 8/26 patients, possible in 16/26, and excluded in 2/26 cases.

Compared with the large TCM study cohort, patients in the liver injury study cohort were older and contained a higher percentage of women, whereas the duration of the hospital stay was similar in both cohorts. The TCM herbs were rarely applied mostly as mixtures consisting of several herbs adding up to 35 different drugs during the patients’ four-week stay. The daily dosage was 95 ± 30 g and thus slightly higher than in the TCM study cohort. Among the many herbal TCM used by the 26 patients in the liver injury cohort, Bupleuri radix and Scuterllariae radix were the two TCM herbs most frequently implicated in liver injury, with variable RUCAM-based causality gradings. Most of the patients received one to six TCM drugs that were associated with potential liver injury as evidenced from the scientific literature, e.g., one patient (case 8) received six potentially hepatotoxic herbal TCM drugs during their hospital stay.

The authors concluded that in 26 (0.12%) of 21470 patients treated with herbal TCM, liver injury with ALT values of ≥ 5 × ULN was found, which normalized shortly following treatment cessation, also substantiating causality.

In the discussion section of the paper, the authors comment that the use of TCM is widely considered less risky as compared with synthetic drugs, although data on direct comparisons are not available in support of this view. Populations using herbal TCM, drugs, either alone, or combined experience more drug-induced liver injury (DILI) than herb-induced liver injury (HILI), possibly due to a higher use of drugs. Valid data of incidence and prevalence of HILI caused by TCM herbs are lacking, and respective data cannot be derived from the present study.

This study is most valuable, in my view. Its strength is clearly the huge sample size. Top marks for the authors for publishing it!

Having said that, we need to take the incidence figures with a pinch of salt, I think. In reality they could be much higher because:

- other settings will not be as tightly supervised as the unusual hospital setting;

- in most other situations the quality of the Chinese herbs might be less controlled;

- there could be adulteration;

- there could be contamination.

The ‘elephant in the room’ obviously is the inevitable question about benefit. Like any other treatment, TCM cannot be judged on the basis of its risk but must be evaluated according to its risk/benefit balance. I realise that this was not the subject of the present study, but it is nevertheless crucial: do the benefits of TCM outweigh its risks?

I am not aware that this is the case (but more than willing to consider any sound evidence readers might supply). More importantly, I am not aware of good evidence to show that, for any condition, TCM would be superior in terms of risk/benefit balance than conventional options. This is not a trivial issue: clinicians have the ethical obligation to apply the best (the one with the most positive risk/benefit balance) treatment to their patients.

If I am right, then TCM should not be used in therapeutic routine in or outside hospitals.

If I am right, the ‘First German Hospital of TCM‘ should close asap; it would be violating fundamental ethical principles.

If I am right, the debate about the risks of TCM is almost irrelevant because we simply should not use it.

Or did I misunderstand something here?

What do you think?

Few people would argue that Cochrane reviews tend to be the most rigorous, independent and objective assessments of therapeutic interventions we currently have. Therefore, it is relevant to see what they tell us about the value of acupuncture.

Here is a fascinating overview of all Cochrane reviews of acupuncture. It was compiled by the formidable guys at ‘FRIENDS OF SCIENCE-BEASED MEDICINE‘ in Australia. They gave me the permission to publish it here (thanks Loretta!).

Considering this collective evidence, it would be hard to dispute the conclusion that there is no convincing evidence that acupuncture is an effective therapy, I believe.

What do you think?