risk/benefit

You, the readers of this blog, have spoken!

The WORST PAPER OF 2022 competition has concluded with a fairly clear winner.

To fill in those new to all this: over the last year, I selected articles that struck me as being of particularly poor quality. I then published them with my comments on this blog. In this way, we ended up with 10 papers, and you had the chance to nominate the one that, in your view, stood out as the worst. Votes came in via comments to my last post about the competition and via emails directly to me. A simple count identified the winner.

It is PAUL VARNAS, DC, a graduate of the National College of Chiropractic, US. He is the author of several books and has taught nutrition at the National University of Health Sciences. His award-winning paper is entitled “What is the goal of science? ‘Scientific’ has been co-opted, but science is on the side of chiropractic“. In my view, it is a worthy winner of the award (the runner-up was entry No 10). Here are a few memorable quotes directly from Paul’s article:

- Most of what chiropractors do in natural health care is scientific; it just has not been proven in a laboratory at the level we would like.

- In many ways we are more scientific than traditional medicine because we keep an open mind and study our observations.

- Traditional medicine fails to be scientific because it ignores clinical observations out of hand.

- When you think about it, in natural health care we are much better at utilizing the scientific process than traditional medicine.

But I am surely doing Paul an injustice. To appreciate his article, please read his article in full.

I am especially pleased that this award goes to a chiropractor who informs us about the value of science and research. The two research questions that undoubtedly need answering more urgently than any other in the realm of chiropractic relate to the therapeutic effectiveness and risks of chiropractic. I just had a quick look in Medline and found an almost complete absence of research from 2022 into these two issues. This, I believe, makes the award for the WORST PAPER OF 2022 all the more meaningful.

PS

Yesterday, I wrote to Paul informing him about the good news (as yet, no reply). Once he provides me with a postal address, I will send him a copy of my recent book on chiropractic as his well-earned prize. I have also invited him to contribute a guest post to this blog. Watch this space!

This meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) was aimed at evaluating the effects of massage therapy in the treatment of postoperative pain.

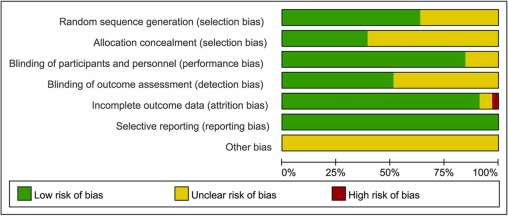

Three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) were searched for RCTs published from database inception through January 26, 2021. The primary outcome was pain relief. The quality of RCTs was appraised with the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool. The random-effect model was used to calculate the effect sizes and standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidential intervals (CIs) as a summary effect. The heterogeneity test was conducted through I2. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were used to explore the source of heterogeneity. Possible publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry.

The analysis included 33 RCTs and showed that MT is effective in reducing postoperative pain (SMD, -1.32; 95% CI, −2.01 to −0.63; p = 0.0002; I2 = 98.67%). A similarly positive effect was found for both short (immediate assessment) and long terms (assessment performed 4 to 6 weeks after the MT). Neither the duration per session nor the dose had a significant impact on the effect of MT, and there was no difference in the effects of different MT types. In addition, MT seemed to be more effective for adults. Furthermore, MT had better analgesic effects on cesarean section and heart surgery than orthopedic surgery.

The authors concluded that MT may be effective for postoperative pain relief. We also found a high level of heterogeneity among existing studies, most of which were compromised in the methodological quality. Thus, more high-quality RCTs with a low risk of bias, longer follow-up, and a sufficient sample size are needed to demonstrate the true usefulness of MT.

The authors discuss that publication bias might be possible due to the exclusion of all studies not published in English. Additionally, the included RCTs were extremely heterogeneous. None of the included studies was double-blind (which is, of course, not easy to do for MT). There was evidence of publication bias in the included data. In addition, there is no uniform evaluation standard for the operation level of massage practitioners, which may lead to research implementation bias.

Patients who have just had an operation and are in pain are usually thankful for the attention provided by carers. It might thus not matter whether it is provided by a massage or other therapist. The question is: does it matter? For the patient, it probably doesn’t; However, for making progress, it does, in my view.

In the end, we have to realize that, with clinical trials of certain treatments, scientific rigor can reach its limits. It is not possible to conduct double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of MT. Thus we can only conclude that, for some indications, massage seems to be helpful (and almost free of adverse effects).

This is also the conclusion that has been drawn long ago in some countries. In Germany, for instance, where I trained and practiced in my younger years, Swedish massage therapy has always been an accepted, conventional form of treatment (while exotic or alternative versions of massage therapy had no place in routine care). And in Vienna where I was chair of rehab medicine I employed about 8 massage therapists in my department.

Animals cannot consent to the treatments they are given when ill. This renders the promotion and use of SCAM in animals a tricky issue. This systematic review assessed the evidence for the clinical efficacy of 24 so-called alternative medicines (SCAMs) used in cats, dogs, and horses.

A bibliographic search, restricted to studies in cats, dogs, and horses, was performed on Web of Science Core Collection, CABI, and PubMed. Relevant articles were assessed for scientific quality, and information was extracted on study characteristics, species, type of treatment, indication, and treatment effects.

Of 982 unique publications screened, 42 were eligible for inclusion, representing 9 different SCAM therapies, which were

- aromatherapy,

- gold therapy,

- homeopathy,

- leeches (hirudotherapy),

- mesotherapy,

- mud,

- neural therapy,

- sound (music) therapy,

- vibration therapy.

For 15 predefined therapies, no study was identified. The risk of bias was assessed as high in 17 studies, moderate to high in 10, moderate in 10, low to moderate in four, and low in one study. In those studies where the risk of bias was low to moderate, there was considerable heterogeneity in reported treatment effects.

The authors concluded that the present systematic review has revealed significant gaps in scientific knowledge regarding the effects of a number of “miscellaneous” SCAM methods used in cats, dogs, and horses. For the majority of the therapies, no relevant scientific articles were retrieved. For nine therapies, some research documentation was available. However, due to small sample sizes, a lack of control groups, and other methodological limitations, few articles with a low risk of bias were identified. Where beneficial results were reported, they were not replicated in other independent studies. Many of the articles were in the lower levels of the evidence pyramid, emphasising the need for more high-quality research using precise methodologies to evaluate the potential therapeutic effects of these therapies. Of the publications that met the inclusion criteria, the majority did not have any scientific documentation of sufficient quality to draw any conclusion regarding their effect. Several of our observations may be translated into lessons on how to improve the scientific support for SCAM therapies. Crucial efforts include (a) a focus on the evaluation of therapies with an explanatory model for a mechanism of action accepted by the scientific community at large, (b) the use of appropriate control animals and treatments, preferably in randomized controlled trials, (c) high-quality observational studies with emphasis on control for confounding factors, (d) sufficient statistical power; to achieve this, large-scale multicenter trials may be needed, (e) blinded evaluations, and (f) replication studies of therapies that have shown promising results in single studies.

What the authors revealed in relation to homeopathy was particularly interesting, in my view. The included studies, with moderate risk of bias, such as homeopathic hypotensive treatment in dogs with early, stage two heart failure and the study on cats with hyperthyroidism, showed no differences between treated and non-treated animals. An RCT with osteoarthritic dogs showed a difference in three of the six variables (veterinary-assessed mobility, two force plate variables, an owner-assessed chronic pain index, and pain and movement visually analogous scales).

The results on homeopathy are supported by another systematic review of 18 RCTs, representing four species (including two dog studies) and 11 indications. The authors excluded generalized conclusions about the effect of certain homeopathic remedies or the effect of individualized homeopathy on a given medical condition in animals. In addition, a meta-analysis of nine homeopathy trials with a high risk of bias, and two studies with a lower risk of bias, concluded that there is very limited evidence that clinical intervention in animals using homeopathic remedies can be distinguished from similar placebo interventions.

In essence, this review confirms what I have been pointing out numerous times: SCAM for animals is not evidence-based, and this includes in particular homeopathy. It follows that its use in animals as an alternative to treatments with proven effectiveness borders on animal abuse.

Is so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) compatible with Christian beliefs? This is not a question that often robs me of my sleep, yet it seems an interesting issue to explore during the Christmas holiday. So, I did a few searches and – would you believe it? – found a ‘Christian Checklist’ as applied to SCAM Since it is by no means long, let me present it to you in full:

- Taking into consideration the lack of scientific evidence available, can it be recommended with integrity?

- What are its roots? Is there an eastern religious basis (Taoism or Hinduism)? Is it based on life force or vitalism?

- Are there any specific spiritual dangers involved? Does its method of diagnosis or practice include occult practices, all forms of which are strictly forbidden in Scripture.

Now, let me try to answer the questions that the checklist poses:

- No! – particularly not, if the SCAM endangers the health of the person who uses it (which, as we have discussed so often can occur in multiple ways).

- Most SCAMs have their roots in eastern religions, life force, or vitalism. Very few are based on Christian ideas or assumptions.

- If we define ‘occult’ as anything that is hidden or mysterious, we are bound to see that almost all SCAMs are occult.

What surprises me with the ‘Christian Checklist’ is that it makes no mention of ethics. I would have thought that this might be an important issue for Christians. Am I mistaken? I have often pointed out that the practice of SCAM nearly invariably violates fundamental rules of ethics.

In any case, the checklist makes one thing quite clear: by and large, SCAM is nothing that Christians should ever contemplate employing. This article (which I have quoted before) seems to confirm my point:

The Vatican’s top exorcist has spoken out in condemnation of yoga … , branding [it] as “Satanic” acts that lead[s] to “demonic possession”. Father Cesare Truqui has warned that the Catholic Church has seen a recent spike in worldwide reports of people becoming possessed by demons and that the reason for the sudden uptick is the rise in popularity of pastimes such as watching Harry Potter movies and practicing Vinyasa.

Professor Giuseppe Ferrari … says that … activities such as yoga, “summon satanic spirits” … Monsignor Luigi Negri, the archbishop of Ferrara-Comacchio, who also attended the Vatican crisis meeting, claimed that homosexuality is “another sign” that “Satan is in the Vatican”. The Independent reports: Father Cesare says he’s seen many an individual speaking in tongues and exhibiting unearthly strength, two attributes that his religion says indicate the possibility of evil spirits inhabiting a person’s body. “There are those who try to turn people into vampires and make them drink other people’s blood, or encourage them to have special sexual relations to obtain special powers,” stated Professor Ferrari at the meeting. “These groups are attracted by the so-called beautiful young vampires that we’ve seen so much of in recent years.”

You might take such statements not all that seriously – the scorn of the vatican does not concern you?

Yet, the ‘Christian Checklist’ also raises worries much closer to home. King Charles is the head of the Anglican Church. Undeniably, he also is a long-term, enthusiastic supporter of many of those ‘quasi-satanic’ SCAMs. How are we supposed to reconsile these contradictions, tensions, and conflicts?

Please advise!

The purpose of this review was to

- identify and map the available evidence regarding the effectiveness and harms of spinal manipulation and mobilisation for infants, children and adolescents with a broad range of conditions;

- identify and synthesise policies, regulations, position statements and practice guidelines informing their clinical use.

Two reviewers independently screened and selected the studies, extracted key findings and assessed the methodological quality of included papers. A descriptive synthesis of reported findings was undertaken using a level-of-evidence approach.

Eighty-seven articles were included. Their methodological quality varied. Spinal manipulation and mobilisation are being utilised clinically by a variety of health professionals to manage paediatric populations with

- adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS),

- asthma,

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

- autism spectrum disorder (ASD),

- back/neck pain,

- breastfeeding difficulties,

- cerebral palsy (CP),

- dysfunctional voiding,

- excessive crying,

- headaches,

- infantile colic,

- kinetic imbalances due to suboccipital strain (KISS),

- nocturnal enuresis,

- otitis media,

- torticollis,

- plagiocephaly.

The descriptive synthesis revealed: no evidence to explicitly support the effectiveness of spinal manipulation or mobilisation for any condition in paediatric populations. Mild transient symptoms were commonly described in randomised controlled trials and on occasion, moderate-to-severe adverse events were reported in systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials and other lower-quality studies. There was strong to very strong evidence for ‘no significant effect’ of spinal manipulation for managing

- asthma (pulmonary function),

- headache,

- nocturnal enuresis.

There was inconclusive or insufficient evidence for all other conditions explored. There is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding spinal mobilisation to treat paediatric populations with any condition.

The authors concluded that, whilst some individual high-quality studies demonstrate positive results for some conditions, our descriptive synthesis of the collective findings does not provide support for spinal manipulation or mobilisation in paediatric populations for any condition. Increased reporting of adverse events is required to determine true risks. Randomised controlled trials examining effectiveness of spinal manipulation and mobilisation in paediatric populations are warranted.

Perhaps the most important findings of this review relate to safety. They confirm (yet again) that there is only limited reporting of adverse events in this body of research. Six reviews, eight RCTs and five other studies made no mention of adverse events or harms associated with spinal manipulation. This, in my view, amounts to scientific misconduct. Four systematic reviews focused specifically on adverse events and harms. They revealed that adverse events ranged from mild to severe and even death.

In terms of therapeutic benefit, the review confirms the findings from the previous research, e.g.:

- Green et al (Green S, McDonald S, Murano M, Miyoung C, Brennan S. Systematic review of spinal manipulation in children: review prepared by Cochrane Australia for Safer Care Victoria. Melbourne, Victoria: Victorian Government 2019. p. 1–67.) explored the effectiveness and safety of spinal manipulation and showed that spinal manipulation should – due to a lack of evidence and potential risk of harm – be recommended as a treatment of headache, asthma, otitis media, cerebral palsy, hyperactivity disorders or torticollis.

- Cote et al showed that evidence is lacking to support the use of spinal manipulation to treat non-musculoskeletal disorders.

In terms of risk/benefit balance, the conclusion could thus not be clearer: no matter whether chiropractors, osteopaths, physiotherapists, or any other healthcare professionals propose to manipulate the spine of your child, DON’T LET THEM DO IT!

This Cochrane review assessed the effectiveness and safety of oral homeopathic medicinal products compared with placebo or conventional therapy to prevent and treat acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) in children.

The researchers included double‐blind randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or double‐blind cluster‐RCTs comparing oral homeopathy medicinal products with placebo or self‐selected conventional treatments to prevent or treat ARTIs in children aged 0 to 16 years.

In this 2022 update, the researchers identified three new RCTs involving 251 children, for a total of 11 included RCTs with 1813 children receiving oral homeopathic medicinal products or a control treatment for ARTIs. All studies focused on upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), with only one study including some lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs). Six RCTs examined the effect on URTI recovery, and five RCTs investigated the effect on preventing URTIs after one to four months of treatment. Two treatment and three prevention studies involved homeopaths individualizing treatment. The other studies used predetermined, non-individualized remedies. All studies involved highly diluted homeopathic medicinal products, with dilutions ranging from 1 x 10‐4 to 1 x 10‐200.

Several limitations to the included studies were identified, in particular methodological inconsistencies and high attrition rates, failure to conduct intention‐to‐treat analysis, selective reporting, and apparent protocol deviations. Three studies were classified as at high risk of bias in at least one domain, and many studies had additional domains with unclear risk of bias. Four studies received funding from homeopathy manufacturers; one study support from a non‐government organization; two studies government support; one study was co‐sponsored by a university; and three studies did not report funding support.

The authors concluded that the “pooling of five prevention and six treatment studies did not show any consistent benefit of homeopathic medicinal products compared to placebo on ARTI recurrence or cure rates in children. We assessed the certainty of the evidence as low to very low for the majority of outcomes. We found no evidence to support the efficacy of homeopathic medicinal products for ARTIs in children. Adverse events were poorly reported, and we could not draw conclusions regarding safety.”

____________________________

These findings are hardly surprising. Will they change the behavior of homeopaths who feel that

- children respond particularly well to homeopathy,

- ARTIs are conditions for which homeopathy is particularly effective?

I would not hold my breath!

Like traditional acupuncture, “cosmetic acupuncture” involves the insertion of needles into the skin. Also called facial rejuvenation acupuncture, cosmetic acupuncture is believed to stimulate collagen and therefore reduce the look of wrinkles. They also claim that cosmetic acupuncture rejuvenates your skin by improving your overall energy and is a great addition to your overall wellness routine – at least, this is what enthusiasts want us to believe.

No surprise then that many consumers give cosmetic acupuncture a try. But what, if after paying for a session, you don’t notice any difference? What, if you even look worse than before?

Impossible?

Not at all! One of the few studies on the subject showed that about half of the clients complained of blotchiness and hyperpigmented spots.

Cosmetic acupuncturists are well prepared for this argument and claim that the treatment will take longer to show any results: “Most cosmetic acupuncture treatments are meant to be taken in a series, generally in a group of 10,” says DiLibero. “The effects of acupuncture are cumulative, so follow-up appointments are recommended.”

And what does the evidence tell us about the effectiveness of cosmetic acupuncture?

One study showed “promising results as a therapy for facial elasticity”. Another one “showed clinical potential for facial wrinkles and laxity.”

That’s great!

No, it isn’t; the studies were published in 3rd class journals and did not even have control groups. Sorry, but I don’t call this evidence. In fact, the type of study that merits the term has not emerged. In other words, cosmetic acupuncture is a swindle!

But at least cosmetic acupuncture is not harmful.

Wrong!

- It will cost you a lot of money because the therapist will persuade you that you need 10 treatment sessions or more.

- It can cause blotchiness and hyperpigmented spots, as mentioned above.

- It has been reported to cause extensive facial sclerosing lipogranulomatosis.

So, you want to improve your looks?

I am not sure what therapies work for this purpose. But I do know that cosmetic acupuncture isn’t one of them.

Osteopathy is currently regulated in 12 European countries: Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Iceland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Switzerland, and the UK. Other countries such as Belgium and Norway have not fully regulated it. In Austria, osteopathy is not recognized or regulated. The Osteopathic Practitioners Estimates and RAtes (OPERA) project was developed as a Europe-based survey, whereby an updated profile of osteopaths not only provides new data for Austria but also allows comparisons with other European countries.

A voluntary, online-based, closed-ended survey was distributed across Austria in the period between April and August 2020. The original English OPERA questionnaire, composed of 52 questions in seven sections, was translated into German and adapted to the Austrian situation. Recruitment was performed through social media and an e-based campaign.

The survey was completed by 338 individuals (response rate ~26%), of which 239 (71%) were female. The median age of the responders was 40–49 years. Almost all had preliminary healthcare training, mainly in physiotherapy (72%). The majority of respondents were self-employed (88%) and working as sole practitioners (54%). The median number of consultations per week was 21–25 and the majority of respondents scheduled 46–60 minutes for each consultation (69%).

The most commonly used diagnostic techniques were: palpation of position/structure, palpation of tenderness, and visual inspection. The most commonly used treatment techniques were cranial, visceral, and articulatory/mobilization techniques. The majority of patients estimated by respondents consulted an osteopath for musculoskeletal complaints mainly localized in the lumbar and cervical region. Although the majority of respondents experienced a strong osteopathic identity, only a small proportion (17%) advertise themselves exclusively as osteopaths.

The authors concluded that this study represents the first published document to determine the characteristics of the osteopathic practitioners in Austria using large, national data. It provides new information on where, how, and by whom osteopathic care is delivered. The information provided may contribute to the evidence used by stakeholders and policy makers for the future regulation of the profession in Austria.

This paper reveals several findings that are, I think, noteworthy:

- Visceral osteopathy was used often or very often by 84% of the osteopaths.

- Muscle energy techniques were used often or very often by 53% of the osteopaths.

- Techniques applied to the breasts were used by 59% of the osteopaths.

- Vaginal techniques were used by 49% of the osteopaths.

- Rectal techniques were used by 39% of the osteopaths.

- “Taping/kinesiology tape” was used by 40% of osteopaths.

- Applied kinesiology was used by 17% of osteopaths and was by far the most-used diagnostic approach.

Perhaps the most worrying finding of the entire paper is summarized in this sentence: “Informed consent for oral techniques was requested only by 10.4% of respondents, and for genital and rectal techniques by 21.0% and 18.3% respectively.”

I am lost for words!

I fail to understand what meaningful medical purpose the fingers of an osteopath are supposed to have in a patient’s vagina or rectum. Surely, putting them there is a gross violation of medical ethics.

Considering these points, I find it impossible not to conclude that far too many Austrian osteopaths practice treatments that are implausible, unproven, potentially harmful, unethical, and illegal. If patients had the courage to take action, many of these charlatans would probably spend some time in jail.

Yesterday, the post brought me a nice Christmas present. For many months, I had been working on updating and extending a book of mine. Then there were some delays at the publisher, but now it is out – what a delight!

The previous edition contained my evidence-based assessments of 150 alternative modalities (therapies and diagnostic techniques). This already was by no means an easy task. The new edition has 202 short, easy-to-understand, and fully-referenced chapters, each on a different modality. I am quite proud of the achievement. Let me just show you the foreword to the new edition:

Alternative medicine is full of surprises. For me, a big surprise was that the first edition of this book was so successful that I was invited to do a second one. I do this, of course, with great pleasure.

So, what is new? I have made two main alterations. Firstly, I updated the previous text by adding new evidence where it had emerged. Secondly, I added many more modalities—52, to be exact.

To the best of my knowledge, this renders the new edition of this book the most comprehensive reference text on alternative medicine available to date. It informs you about the nature, proven benefits, and potential risks of 202 different diagnostic methods and therapeutic interventions from the realm of so-called alternative medicine. If you use this information wisely, it could save you a lot of money. One day, it might even save your life.

I hope you enjoy using this book as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Like the first edition, the book is not about promoting so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) nor about the opposite. It is about evaluating SCAM critically but fairly. In other words, each subject had to be researched and the evidence for or against it explained such that a layperson will comprehend it. This proved to be a colossal task.

The end result will not please the many believers in SCAM, I am afraid. Yet, I hope it will suit those who realize that, in healthcare, progress is generated not through belief but through critical evaluation of the evidence.

Is acupuncture more than a theatrical placebo? Acupuncture fans are convinced that the answer to this question is YES. Perhaps this paper will make them think again.

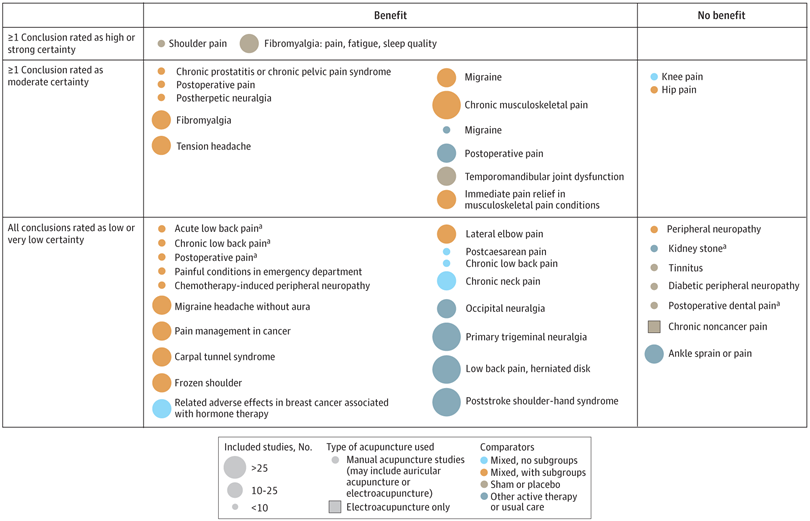

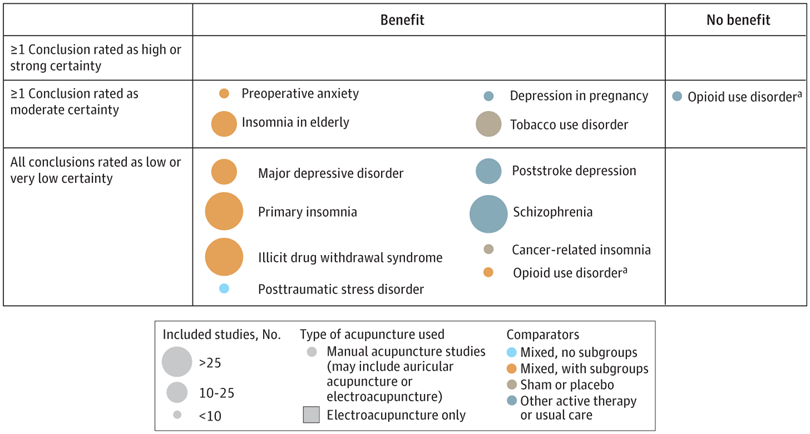

A new analysis mapped the systematic reviews, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence for outcomes of acupuncture as a treatment for adult health conditions. Computerized search of PubMed and 4 other databases from 2013 to 2021. Systematic reviews of acupuncture (whole body, auricular, or electroacupuncture) for adult health conditions that formally rated the certainty, quality, or strength of evidence for conclusions. Studies of acupressure, fire acupuncture, laser acupuncture, or traditional Chinese medicine without mention of acupuncture were excluded. Health condition, number of included studies, type of acupuncture, type of comparison group, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence. Reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as high-certainty evidence, reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as moderate-certainty evidence and reviews with all conclusions rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence; full list of all conclusions and certainty of evidence.

A total of 434 systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions were found; of these, 127 reviews used a formal method to rate the certainty or quality of evidence of their conclusions, and 82 reviews were mapped, covering 56 health conditions. Across these, there were 4 conclusions that were rated as high-certainty evidence and 31 conclusions that were rated as moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions (>60) were rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence. Approximately 10% of conclusions rated as high or moderate-certainty were that acupuncture was no better than the comparator treatment, and approximately 75% of high- or moderate-certainty evidence conclusions were about acupuncture compared with a sham or no treatment.

Three evidence maps (pain, mental conditions, and other conditions) are shown below

The authors concluded that despite a vast number of randomized trials, systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions have rated only a minority of conclusions as high- or moderate-certainty evidence, and most of these were about comparisons with sham treatment or had conclusions of no benefit of acupuncture. Conclusions with moderate or high-certainty evidence that acupuncture is superior to other active therapies were rare.

These findings are sobering for those who had hoped that acupuncture might be effective for a range of conditions. Despite the fact that, during recent years, there have been numerous systematic reviews, the evidence remains negative or flimsy. As 34 reviews originate from China, and as we know about the notorious unreliability of Chinese acupuncture research, this overall result is probably even more negative than the authors make it out to be.

Considering such findings, some people (including the authors of this analysis) feel that we now need more and better acupuncture trials. Yet I wonder whether this is the right approach. Would it not be better to call it a day, concede that acupuncture generates no or only relatively minor effects, and focus our efforts on more promising subjects?