physiotherapists

Subluxation is … a displacement of two or more bones whose articular surfaces have lost, wholly or in part, their natural connection. (D. D. Palmer, 1910)

The definition of ‘subluxation’ as used by chiropractors differs from that in conventional medicine where it describes a partial dislocation of the bony surfaces of a joint readily visible via an X-ray. Crucially, a subluxation, as understood in conventional medicine, is not the cause of disease. Spinal subluxations, according to medical terminology, are possible only if anatomical structures are seriously disrupted.

Subluxation, as chiropractors understand the term, has been central to chiropractic from its very beginning. Despite its central role in chiropractic, its definition is far from clear and has changed significantly over time.

DD Palmer (the guy who invented chiropractic) was extremely vague about most of his ideas. Yet, he remained steadfast about his claims that 95% of all diseases were due to subluxations of the spine, that subluxations hindered the flow of the ‘innate intelligence’ which controlled the vital functions of the body. Innate intelligence or ‘inate’, he believed, operated through the nerves, and subluxated vertebra caused pinched nerves, which in turn blocked the flow of the innate and thus led to abnormal function of our organs. For Palmer and his followers, subluxation is the sole or at least the main cause of all diseases (or dis-eases, as Palmer preferred).

Almost exactly 4 years ago, I published this post:

Is chiropractic subluxation a notion of the past? SADLY NOT!

In it, I provided evidence that – contrary to what we are often told – chiropractors remain fond of the subluxation nonsense they leant in school. This can be shown by the frequency by which chiropractors advertise on Twitter the concept of chiropractic subluxation.

Today, I had another look. The question I asked myself was: has the promotion of the obsolete subluxation concept by chiropractors subsided?

The findings did not surprise me.

Even a quick glance reveals that there is still a plethora of advertising going on that uses the subluxation myth. Many chiros use imaginative artwork to get their misleading message across. Below is a small selection.

Yes, I know, this little display is not very scientific. In fact, it is a mere impression and does not intend to be anything else. So, let’s look at some more scientific data on this subject. Here are the last 2 paragraphs from the chapter on subluxation in my recent book on chiropractic:

A 2018 survey determined how many chiropractic institutions worldwide still use the term in their curricula.[1] Forty-six chiropractic programmes (18 from US and 28 non-US) participated. The term subluxation was found in all but two US course catalogues. Remarkably, between 2011 and 2017, the use of subluxation in US courses even increased. Similarly, a survey of 7455 US students of chiropractic showed that 61% of them agreed or strongly agreed that the emphasis of chiropractic intervention is to eliminate vertebral subluxations/vertebral subluxation complexes.[2]

Even though chiropractic subluxation is at the heart of chiropractic, its definition remains nebulous and its very existence seems doubtful. But doubt is not what chiropractors want. Without subluxation, spinal manipulation seems questionable – and this will be the theme of the next chapter.

[1] https://chiromt.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12998-018-0191-1

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25646145

In a nutshell: chiros cannot give up the concept of subluxation because, if they did, they would be physios except with a much narrower focus.

I recently came across this paper by Prof. Dr. Chad E. Cook, a physical therapist, PhD, a Fellow of the American Physical Therapy Association (FAPTA), and a professor as well as director of clinical research in the Department of Orthopaedics, Department of Population Health Sciences at the Duke Clinical Research Institute at Duke University in North Carolina, USA. The paper is entitled ‘The Demonization of Manual Therapy‘.

Cook introduced the subject by stating: “In medicine, when we do not understand or when we dislike something, we demonize it. Well-known examples throughout history include the initial ridicule of antiseptic handwashing, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (i. e., balloon angioplasty), the relationships between viruses and cancer, the contribution of bacteria in the development of ulcers, and the role of heredity in the development of disease. In each example, naysayers attempted to discredit the use of each of the concepts, despite having no evidence to support their claims. The goal in each of the aforementioned topics: demonize the concept.”

Cook then discussed 8 ‘demonizations’ of manual therapy. Number 7 is entitled “Causes as Much Harm as Help“. Here is this section in full:

By definition, harms include adverse reactions (e. g., side effects of treatments), and other undesirable consequences of health care products and services. Harms can be classified as “none”, minor, moderate, serious and severe [67]. Most interventions have some harms, typically minor, which are defined as a non-life-threatening, temporary harm that may or may not require efforts to assess for a change in a patient’s condition such as monitoring [67].

There are harms associated with a manual therapy intervention, but they are generally benign (minor). Up to 20 –40 % of individuals will report adverse events after the application of manual therapy. The most common adverse events were soreness in muscles, increased pain, stiffness and tiredness [68]. There are rare occasions of several harms associated with manual therapy and these include spinal or neurological problems as well as cervical arterial strokes [9]. It is critical to emphasize how rare these events are; serious adverse event incidence estimates ranged from 1 per 2 million manipulations to 13 per 10,000 patients [69].

Cook then concludes that “manual therapy has been inappropriately demonized over the last decade and has been associated with inaccurate assumptions and false speculations that many clinicians have acquired over the last decade. This paper critically analyzed eight of the most common assumptions that have belabored manual therapy and identified notable errors in seven of the eight. It is my hope that the physiotherapy community will carefully re-evaluate its stance on manual therapy and consider a more evidence-based approach for the betterment of our patients.

REFERENCES

[9] Ernst E. Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review. J R Soc Med 2007; 100: 330–338.doi:10.1177/014107680710000716 [68] Paanalahti K, Holm LW, Nordin M et al. Adverse events after manual therapy among patients seeking care for neck and/or back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 77. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-77 [69] Swait G, Finch R. What are the risks of manual treatment of the spine? A scoping review for clinicians. Chiropr Man Therap 2017; 25: 37. doi:10.1186/s12998-017-0168-5

_________________________________

Here are a few things that I find odd or wrong with Cook’s text:

- The term ‘demonizing’ seems to be a poor choice. The historical examples chosen by Cook were not cases of demonization. They were mostly instances where new discoveries did not fit into the thinking of the time and therefore took a long time to get accepted. They also show that sooner or later, sound evidence always prevails. Lastly, they suggest that speeding up this process via the concept of evidence-based medicine is a good idea.

- Cook then introduces the principle of risk/benefit balance by entitling the cited section “Causes as Much Harm as Help“. Oddly, however, he only discusses the risks of manual therapies and omits the benefit side of the equation.

- This omission is all the more puzzling since he quotes my paper (his reference [9]) states that “the effectiveness of spinal manipulation for most indications is less than convincing.5 A risk-benefit evaluation is therefore unlikely to generate positive results: with uncertain effectiveness and finite risks, the balance cannot be positive.”

- In discussing the risks, he seems to assume that all manual therapies are similar. This is clearly not true. Massage therapies have a very low risk, while this cannot be said of spinal manipulations.

- The harms mentioned by Cook seem to be those of spinal manipulation and not those of all types of manual therapy.

- Cook states that “up to 20 –40 % of individuals will report adverse events after the application of manual therapy.” Yet, the reference he uses in support of this statement is a clinical trial that reported an adverse effect rate of 51%.

- Cook then states that “there are rare occasions of several harms associated with manual therapy and these include spinal or neurological problems as well as cervical arterial strokes.” In support, he quotes one of my papers. In it, I emphasize that “the incidence of such events is unknown.” Cook not only ignores this fact but states in the following sentence that “it is critical to emphasize how rare these events are…”

Cook concludes that “manual therapy has been inappropriately demonized over the last decade and has been associated with inaccurate assumptions and false speculations …” He confuses, I think, demonization with critical assessment.

Cook’s defence of manual therapy is clumsy, inaccurate, ill-conceived, misleading and often borders on the ridiculous. In the age of evidence-based medicine, therapies are not ‘demonized’ but evaluated on the basis of their effectiveness and safety. Manual therapies are too diverse to do this wholesale. They range from various massage techniques, some of which have a positive risk/benefit balance, to high-velocity, low-amplitude thrusts, for which the risks do not demonstrably outweigh the benefits.

Spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) is widely used worldwide to treat musculoskeletal and many other conditions. The evidence that it works for any of them is weak, non-existent, or negative. What is worse, SMT can – as we have discussed so often on this blog – cause adverse events some of which are serious, even fatal.

Spinal epidural hematoma (SEH) caused by SMT is a rare emergency that can cause neurological dysfunction. Chinese researchers recently reported three cases of SEH after SMT.

- The first case was a 30-year-old woman who experienced neck pain and numbness in both upper limbs immediately after SMT. Her symptoms persisted after 3 d of conservative treatment, and she was admitted to our hospital. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated an SEH, extending from C6 to C7.

- The second case was a 55-year-old man with sudden back pain 1 d after SMT, numbness in both lower limbs, an inability to stand or walk, and difficulty urinating. MRI revealed an SEH, extending from T1 to T3.

- The third case was a 28-year-old man who suddenly developed symptoms of numbness in both lower limbs 4 h after SMT. He was unable to stand or walk and experienced mild back pain. MRI revealed an SEH, extending from T1 to T2.

All three patients underwent surgery after failed conservative treatment and all recovered to ASIA grade E on day 5, 1 wk, and day 10 after surgery, respectively. All patients returned to normal after 3 mo of follow-up.

The authors concluded that SEH caused by SMT is very rare, and the condition of each patient should be evaluated in full detail before operation. SEH should be diagnosed immediately and actively treated by surgery.

These cases might serve as an apt reminder of the fact that SMT (particularly SMT of the neck) is not without its dangers. The authors’ assurance that SEH is VERY RARE is a little puzzling, in my view (the paper includes a table with all 17 previously published cases). There is, as we often have mentioned, no post-marketing surveillance, surgeons only see those patients who survive such complications long enough to come to the hospital, and they publish such cases only if they feel like it. Consequently, the true incidence is anyone’s guess.

As pointed out earlier, the evidence that SMT might be effective is shaky for most indications. In view of the potential for harm, this can mean only one thing:

The risk/benefit balance for SMT is not demonstrably positive.

In turn, this leads to the conclusion that patients should think twice before having SMT and should inquire about other therapeutic options that have a more positive risk/benefit balance. Similarly, the therapists proposing SMT to a patient have the ethical and moral duty to obtain fully informed consent which includes information about the risk/benefit balance of SMT and other options.

A substantial number of patients globally receive spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) to manage non-musculoskeletal disorders. However, the efficacy and effectiveness of these interventions to prevent or treat non-musculoskeletal disorders remain controversial.

A Global Summit of international chiropractors and scientists conducted a systematic review of the literature to determine the efficacy and effectiveness of SMT for the primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of non-musculoskeletal disorders. The Global Summit took place on September 14-15, 2019 in Toronto, Canada. It was attended by 50 chiropractic researchers from 8 countries and 28 observers from 18 chiropractic organizations. Participants met the following criteria: 1) chiropractor with a PhD, or a researcher with a PhD (not a chiropractor) with research expertise in chiropractic; 2) actively involved in research (defined as having published at least 5 peer-reviewed papers over the past 5 years); and 3) appointed at an academic or educational institution. In addition, a small group of researchers who did not meet these criteria were invited. These included three chiropractors with a strong publication and scientific editorial record who did not have a PhD (SMP, JW, and HS) and two early career researchers with expertise within the area of chiropractic and pseudoscience (ALM, GG). Participants were invited by the Steering Committee using purposive and snowball sampling methods. At the summit, participants critically appraised the literature and synthesized the evidence.

They searched MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, and the Index to Chiropractic Literature from inception to May 15, 2019, using subject headings specific to each database and free text words relevant to manipulation/manual therapy, effectiveness, prevention, treatment, and non-musculoskeletal disorders. Eligible for review were randomized controlled trials published in English. The methodological quality of eligible studies was assessed independently by reviewers using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria for randomized controlled trials. The researchers synthesized the evidence from articles with high or acceptable methodological quality according to the Synthesis without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) Guideline. The final risk of bias and evidence tables were reviewed by researchers who attended the Global Summit and 75% (38/50) had to approve the content to reach consensus.

A total of 4997 citations were retrieved, and 1123 duplicates were removed, and 3874 citations were screened. Of those, the eligibility of 32 articles was evaluated at the Global Summit and 16 articles were included in the systematic review. The synthesis included 6 randomized controlled trials with acceptable or high methodological quality (reported in 7 articles). These trials investigated the efficacy or effectiveness of SMT for the management of

- infantile colic,

- childhood asthma,

- hypertension,

- primary dysmenorrhea,

- migraine.

None of the trials evaluated the effectiveness of SMT in preventing the occurrence of non-musculoskeletal disorders. A consensus was reached on the content of all risk of bias and evidence tables. All randomized controlled trials with high or acceptable quality found that SMT was not superior to sham interventions for the treatment of these non-musculoskeletal disorders.

Six of 50 participants (12%) in the Global Summit did not approve the final report.

The authors concluded that our systematic review included six randomized clinical trials (534 participants) of acceptable or high quality investigating the efficacy or effectiveness of SMT for the treatment of non-musculoskeletal disorders. We found no evidence of an effect of SMT for the management of non-musculoskeletal disorders including infantile colic, childhood asthma, hypertension, primary dysmenorrhea, and migraine. This finding challenges the validity of the theory that treating spinal dysfunctions with SMT has a physiological effect on organs and their function. Governments, payers, regulators, educators, and clinicians should consider this evidence when developing policies about the use and reimbursement of SMT for non-musculoskeletal disorders.

I would have formulated the conclusions much more succinctly:

As has already been shown repeatedly, there is no sound evidence that SMT is effective for non-musculoskeletal conditions.

This study describes the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) among older adults who report being hampered in daily activities due to musculoskeletal pain. Cross-sectional European Social Survey (EES) Round 7 (2014) data from 21 countries were examined for participants aged 55 years and older, who reported musculoskeletal pain that hampered daily activities in the past 12months. From a total of 35,063 individuals who took part in the ESS study, 13,016 (37%) were aged 55 or older; of which 8183 (63%) reported the presence of pain, with a further 4950 (38%) reporting that this pain hampered their daily activities in any way.

Of the 4950 older adult participants reporting musculoskeletal pain that hampered daily activities, the majority (63.5%) were from the West of Europe, reported secondary education or less (78.2%), and reported at least one other health-related problem (74.6%). In total, 1657 (33.5%) reported using at least one SCAM treatment in the previous year. Manual body-based therapies (MBBTs) were most used, including massage therapy (17.9%) and osteopathy (7.0%). Alternative medicinal systems (AMSs) were also popular with 6.5% using homeopathy and 5.3% reporting herbal treatments. A general trend of higher SCAM use in younger participants was noted.

SCAM usage was associated with

- physiotherapy use,

- female gender,

- higher levels of education,

- being in employment,

- living in West Europe

- having multiple health problems.

The authors concluded that a third of older Europeans with musculoskeletal pain report SCAM use in the previous

12 months. Certain subgroups with higher rates of SCAM use could be identified. Clinicians should comprehensively and routinely assess SCAM use among older adults with musculoskeletal pain.

Such studies have the advantage of large sample sizes, and therefore one is inclined to consider their findings to be reliable and informative. Yet, they resemble big fishing operations where all sorts of important and unimportant stuff is caught in the net. When studying such papers, it is wise to remember that associations do not necessarily reveal causal relationships!

Having said this, I find very little information in these already outdated results (they originate from 2014!) that I would not have expected. Perhaps the most interesting aspect is the nature of the most popular SCAMs used for musculoskeletal problems. The relatively high usage of MBBTs had to be expected; in most of the surveyed countries, massage therapy is considered to be not SCAM but mainstream. The fact that 6.5% used homeopathy to ease their musculoskeletal pain is, however, quite remarkable. I know of no good evidence to show that homeopathy is effective for such problems (in case some homeopathy fans disagree, please show me the evidence).

In my view, this indicates that, in 2014, much needed to be done in terms of informing the public about homeopathy. Many consumers mistook homeopathy for herbal medicine (which btw may well have some potential for musculoskeletal pain), and many consumers had been misguided into believing that homeopathy works. They had little inkling that homeopathy is pure placebo therapy. This means they mistreated their conditions, continued to suffer needlessly, and caused an unnecessary financial burden to themselves and/or to society.

Since 2014, much has happened (as discussed in uncounted posts on this blog), and I would therefore assume that the 6.5% figure has come down significantly … but, as you know:

I am an optimist.

I believe in progress.

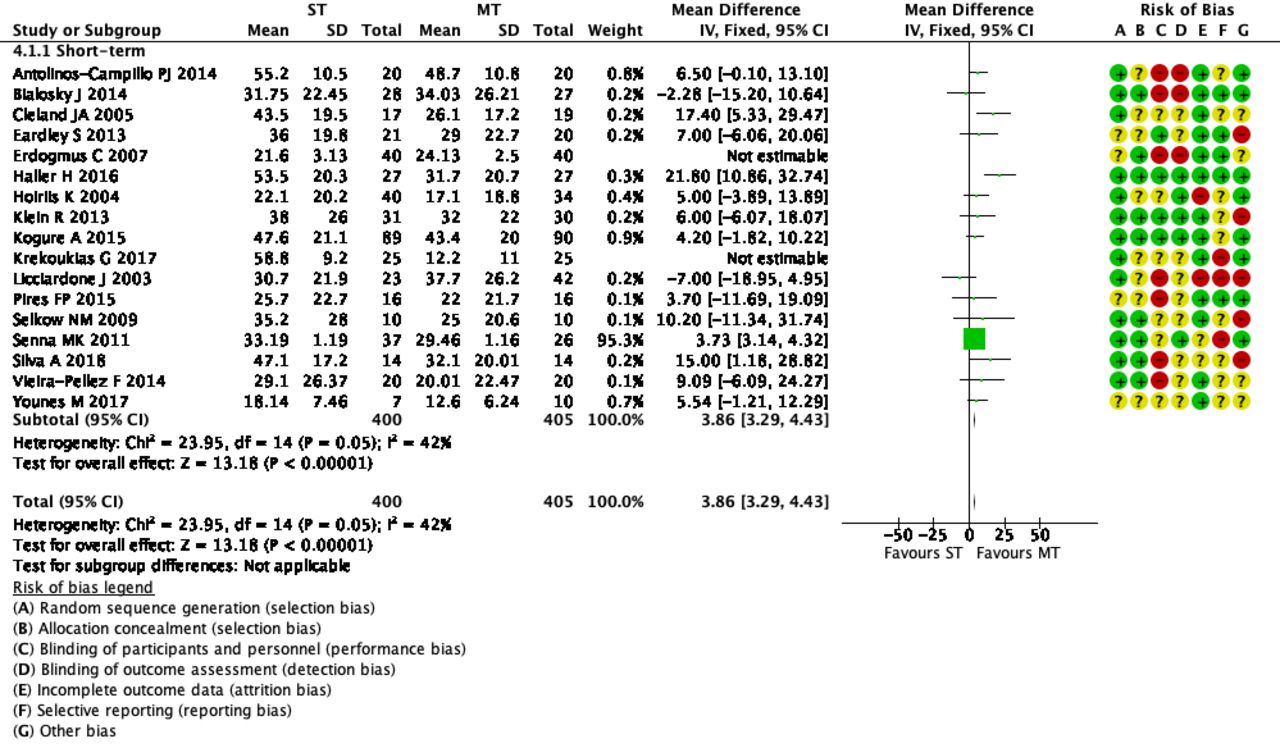

This systematic review assessed the effects and reliability of sham procedures in manual therapy (MT) trials in the treatment of back pain (BP) in order to provide methodological guidance for clinical trial development.

Different databases were screened up to 20 August 2020. Randomized controlled trials involving adults affected by BP (cervical and lumbar), acute or chronic, were included. Hand contact sham treatment (ST) was compared with different MT (physiotherapy, chiropractic, osteopathy, massage, kinesiology, and reflexology) and to no treatment. Primary outcomes were BP improvement, the success of blinding, and adverse effects (AE). Secondary outcomes were the number of drop-outs. Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using risk ratio (RR), continuous using mean difference (MD), 95% CIs. The minimal clinically important difference was 30 mm changes in pain score.

A total of 24 trials were included involving 2019 participants. Most of the trials were of chiropractic manipulation. Very low evidence quality suggests clinically insignificant pain improvement in favor of MT compared with ST (MD 3.86, 95% CI 3.29 to 4.43) and no differences between ST and no treatment (MD -5.84, 95% CI -20.46 to 8.78).ST reliability shows a high percentage of correct detection by participants (ranged from 46.7% to 83.5%), spinal manipulation is the most recognized technique. Low quality of evidence suggests that AE and drop-out rates were similar between ST and MT (RR AE=0.84, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.28, RR drop-outs=0.98, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.25). A similar drop-out rate was reported for no treatment (RR=0.82, 95% 0.43 to 1.55).

The authors concluded that MT does not seem to have clinically relevant effect compared with ST. Similar effects were found with no treatment. The heterogeneousness of sham MT studies and the very low quality of evidence render uncertain these review findings. Future trials should develop reliable kinds of ST, similar to active treatment, to ensure participant blinding and to guarantee a proper sample size for the reliable detection of clinically meaningful treatment effects.

The authors concluded that MT does not seem to have clinically relevant effect compared with ST. Similar effects were found with no treatment. The heterogeneousness of sham MT studies and the very low quality of evidence render uncertain these review findings. Future trials should develop reliable kinds of ST, similar to active treatment, to ensure participant blinding and to guarantee a proper sample size for the reliable detection of clinically meaningful treatment effects.

The optimal therapy for back pain does not exist or has not yet been identified; there are dozens of different approaches but none has been found to be truly and dramatically effective. Manual therapies like chiropractic and osteopathy are often used, and some data suggest that they are as good (or as bad) as most other options. This review confirms what we have discussed many times previously (e.g. here), namely that the small positive effect of MT, or specifically spinal manipulation, is largely due to placebo.

Considering this information, what is the best treatment for back pain sufferers? The answer seems obvious: it is a therapy that is as (in)effective as all the others but causes the least harm or expense. In other words, it is not chiropractic nor osteopathy but exercise.

My conclusion:

avoid therapists who use spinal manipulation for back pain.

A new study evaluated the effects of yoga and eurythmy therapy compared to conventional physiotherapy exercises in patients with chronic low back pain.

In this three-armed, multicentre, randomized trial, patients with chronic low back pain were treated for 8 weeks in group sessions (75 minutes once per week). They received either:

- Yoga exercises

- Eurythmy

- Physiotherapy

The primary outcome was patients’ physical disability (measured by RMDQ) from baseline to week 8. Secondary outcome variables were pain intensity and pain-related bothersomeness (VAS), health-related quality of life (SF-12), and life satisfaction (BMLSS). Outcomes were assessed at baseline, after the intervention at 8 weeks, and at a 16-week follow-up. Data of 274 participants were used for statistical analyses.

The results showed no significant differences between the three groups for the primary and secondary outcomes. In all groups, RMDQ decreased comparably at 8 weeks but did not reach clinical meaningfulness. Pain intensity and pain-related bothersomeness decreased, while the quality of life increased in all 3 groups. In explorative general linear models for the SF-12’s mental health component, participants in the eurythmy arm benefitted significantly more compared to physiotherapy and yoga. Furthermore, within-group analyses showed improvements of SF-12 mental score for yoga and eurythmy therapy only. All interventions were safe.

Everyone knows what physiotherapy or yoga is, I suppose. But what is eurythmy?

It is an exercise therapy that is part of anthroposophic medicine. It consists of a set of specific movements that were developed by Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), the inventor of anthroposophic medicine, in conjunction with Marie von Sievers (1867-1948), his second wife.

Steiner stated in 1923 that eurythmy has grown out of the soil of the Anthroposophical Movement, and the history of its origin makes it almost appear to be a gift of the forces of destiny. Steiner also wrote that it is the task of the Anthroposophical Movement to reveal to our present age that spiritual impulse that is suited to it. He claimed that, within the Anthroposophical Movement, there is a firm conviction that a spiritual impulse of this kind must enter once more into human evolution. And this spiritual impulse must perforce, among its other means of expression, embody itself in a new form of art. It will increasingly be realized that this particular form of art has been given to the world in Eurythmy.

Consumers learning eurythmy are taught exercises that allegedly integrate cognitive, emotional, and volitional elements. Eurythmy exercises are based on speech and direct the patient’s attention to their own perceived intentionality. Proponents of Eurythmy believe that, through this treatment, a connection between internal and external activity can be experienced. They also make many diffuse health claims for this therapy ranging from stress management to pain control.

There is hardly any reliable evidence for eurythmy, and therefore the present study is exceptional and noteworthy. One review concluded that “eurythmy seems to be a beneficial add-on in a therapeutic context that can improve the health conditions of affected persons. More methodologically sound studies are needed to substantiate this positive impression.” This positive conclusion is, however, of doubtful validity. The authors of the review are from an anthroposophical university in Germany. They included studies in their review that were methodologically too weak to allow any conclusions.

So, does the new study provide the reliable evidence that was so far missing? I am afraid not!

The study compared three different exercise therapies. Its results imply that all three were roughly equal. Yet, we cannot tell whether they were equally effective or equally ineffective. The trial was essentially an equivalence study, and I suspect that much larger sample sizes would have been required in order to identify any true differences if they at all exist. Lastly, the study (like the above-mentioned review) was conducted by proponents of anthroposophical medicine affiliated with institutions of anthroposophical medicine. I fear that more independent research would be needed to convince me of the value of eurythmy.

This study compared the effectiveness of two osteopathic manipulative techniques on clinical low back symptoms and trunk neuromuscular postural control in male workers with chronic low back pain (CLBP).

Ten male workers with CLBP were randomly allocated to two groups: high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) manipulation or muscle energy techniques (MET). Each group received one therapy per week for both techniques during 7 weeks of treatment.

Pain and function were measured by using the Numeric Pain-Rating Scale, the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. The lumbar flexibility was assessed by Modified Schober Test. Electromyography (EMG) and force platform measurements were used for evaluation of trunk muscular activation and postural balance, respectively at three different times: baseline, post-intervention, and 15 days later.

Both techniques were effective (p < 0.01) in reducing pain with large clinical differences (-1.8 to -2.8) across immediate and after 15 days. However, no significant effect between groups and times was found for other variables, namely neuromuscular activation, and postural balance measures.

The authors concluded that both techniques (HVLA thrust manipulation and MET) were effective in reducing back pain immediately and 15 days later. Neither technique changed the trunk neuromuscular activation patterns nor postural balance in male workers with LBP.

There is, of course, another conclusion that fits the data just as well: both techniques were equally ineffective.

Osteopathy is hugely popular in France. Despite the fact that osteopathy has never been conclusively shown to generate more good than harm, French osteopaths have somehow managed to get a reputation as trustworthy, evidence-based healthcare practitioners. They tend to treat musculoskeletal and many other issues. Visceral manipulation is oddly popular amongst French osteopaths. Now the trust of the French in osteopathy seems to have received a serious setback.

‘LE PARISIEN‘ has just published an article about the alleged sexual misconduct of one of the most prominent French osteopaths and director of one of the foremost schools of osteopathy in France. Here are some excerpts from the article that I translated for readers who don’t speak French:

The public prosecutor’s office of Grasse (Alpes-Maritimes) has opened a judicial investigation against Marc Bozzetto, the director and founder of the school of osteopathy in Valbonne, accused of rape and sexual assault.

In total, “four victims are targeted by the introductory indictment,” said the prosecutor’s office, stating that Marc Bozzetto had already been placed in police custody since the beginning of the proceedings. The daily paper ‘Nice-Matin’ has listed six complaints and published the testimony of a seventh alleged victim.

This victim claims to have been sexually assaulted in 2013, alleging that, during a professional appointment, Bozzetto had massaged her breasts and her intimate area. “He told me that everything went through my vagina and clitoris, that I had to spread my legs and let the energy flow through my clitoris. That I had to learn how to give myself pleasure on my own,” she told Nice-Matin. The newspaper also recorded the testimonies of a former employee, a top-level sportswoman, an employee from the world of culture, and a former student.

“I take note that a judicial inquiry is open. To date, he has neither been summoned nor indicted,” said Karine Benadava, the Parisian lawyer of the 80-year-old Bozzetto. Her client had already responded following initial accusations from students: “This is a normal feeling for women, but if all the women who work on the pelvis complain, you can’t get away with it and you have to stop working as a pelvic osteopath,” replied Bozzetto. In another interview, he had declared himself “furious” and unable to understand the reaction of these two students.

The school of osteopathy trains about 300 students each five years and presents itself as the first holistic osteopathy campus in France.

______________________________

Such stories of sexual misconduct of practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) are sadly no rarety, particularly those working in the area of manual therapy. They remind me of a case against a Devon SCAM practitioner in which I served as an expert witness many years ago. Numerous women gave witness that he ended up having his fingers in their vagina during therapy. He did not deny the fact but tried to defend himself by claiming that he was merely massaging lymph-nodes in this area. It was my task to elaborate on the plausibility of this claim. The SCAM practitioner in question was eventually sentenced to two years in prison.

It stands to reason that SCAM practitioners working in the pelvic area are at particularly high risk of going atray. The above case might be a good occasion to have a public debate in France and ask: IS VISCERAL OSTEOPATHY EVIDENCE-BASED? The answer is very clearly NO! Surely, this is a message worth noting in view of the current popularity of this ridiculous, costly, and dangerous charlatanry.

And how does one minimize the risk of sexual misconduct of SCAM professionals? The most obvious answer would be, by proper education during their training. In the case mentioned above, this might have been a problem: if the director is into sexual misconduct, what can you expect of the rest of the school? In many other cases, the problem is even greater: many SCAM practitioners have had no training at all, or no training in healthcare ethics to speak of.

I was criticised for not referencing this article in a recent post on adverse effects of spinal manipulation. In fact the commentator wrote: Shame on you Prof. Ernst. You get an “E” for effort and I hope you can do better next time. The paper was published in a third-class journal, but I will nevertheless quote the ‘key messages’ from this paper, because they are in many ways remarkable.

- Adverse events from manual therapy are few, mild, and transient. Common AEs include local tenderness, tiredness, and headache. Other moderate and severe adverse events (AEs) are rare, while serious AEs are very rare.

- Serious AEs can include spinal cord injuries with severe neurological consequences and cervical artery dissection (CAD), but the rarity of such events makes the provision of epidemiological evidence challenging.

- Sports-related practice is often time sensitive; thus, the manual therapist needs to be aware of common and rare AEs specifically associated with spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) to fully evaluate the risk-benefit ratio.

The author of this paper is Aleksander Chaibi, PT, DC, PhD who holds several positions in the Norwegian Chiropractors’ Association, and currently holds a position as an expert advisor in the field of biomedical brain research for the Brain Foundation of the Netherlands. I feel that he might benefit from reading some more critical texts on the subject. In fact, I recommend my own 2020 book. Here are a few passages dealing with the safety of SMT:

Relatively minor AEs after SMT are extremely common. Our own systematic review of 2002 found that they occur in approximately half of all patients receiving SMT. A more recent study of 771 Finish patients having chiropractic SMT showed an even higher rate; AEs were reported in 81% of women and 66% of men, and a total of 178 AEs were rated as moderate to severe. Two further studies reported that such AEs occur in 61% and 30% of patients. Local or radiating pain, headache, and tiredness are the most frequent adverse effects…

A 2017 systematic review identified the characteristics of AEs occurring after cervical spinal manipulation or cervical mobilization. A total of 227 cases were found; 66% of them had been treated by chiropractors. Manipulation was reported in 95% of the cases, and neck pain was the most frequent indication for the treatment. Cervical arterial dissection (CAD) was reported in 57%, and 46% had immediate onset symptoms. The authors of this review concluded that there seems to be under-reporting of cases. Further research should focus on a more uniform and complete registration of AEs using standardized terminology…

In 2005, I published a systematic review of ophthalmic AEs after SMT. At the time, there were 14 published case reports. Clinical symptoms and signs included:

- central retinal artery occlusion,

- nystagmus,

- Wallenberg syndrome,

- ptosis,

- loss of vision,

- ophthalmoplegia,

- diplopia,

- Horner’s syndrome…

Vascular accidents are the most frequent serious AEs after chiropractic SMT, but they are certainly not the only complications that have been reported. Other AEs include:

- atlantoaxial dislocation,

- cauda equina syndrome,

- cervical radiculopathy,

- diaphragmatic paralysis,

- disrupted fracture healing,

- dural sleeve injury,

- haematoma,

- haematothorax,

- haemorrhagic cysts,

- muscle abscess,

- muscle abscess,

- myelopathy,

- neurologic compromise,

- oesophageal rupture

- pneumothorax,

- pseudoaneurysm,

- soft tissue trauma,

- spinal cord injury,

- vertebral disc herniation,

- vertebral fracture…

In 2010, I reviewed all the reports of deaths after chiropractic treatments published in the medical literature. My article covered 26 fatalities but it is important to stress that many more might have remained unpublished. The cause usually was a vascular accident involving the dissection of a vertebral artery (see above). The review also makes the following important points:

- … numerous deaths have been associated with chiropractic. Usually high-velocity, short-lever thrusts of the upper spine with rotation are implicated. They are believed to cause vertebral arterial dissection in predisposed individuals which, in turn, can lead to a chain of events including stroke and death. Many chiropractors claim that, because arterial dissection can also occur spontaneously, causality between the chiropractic intervention and arterial dissection is not proven. However, when carefully evaluating the known facts, one does arrive at the conclusion that causality is at least likely. Even if it were merely a remote possibility, the precautionary principle in healthcare would mean that neck manipulations should be considered unsafe until proven otherwise. Moreover, there is no good evidence for assuming that neck manipulation is an effective therapy for any medical condition. Thus, the risk-benefit balance for chiropractic neck manipulation fails to be positive.

- Reliable estimates of the frequency of vascular accidents are prevented by the fact that underreporting is known to be substantial. In a survey of UK neurologists, for instance, under-reporting of serious complications was 100%. Those cases which are published often turn out to be incomplete. Of 40 case reports of serious adverse effects associated with spinal manipulation, nine failed to provide any information about the clinical outcome. Incomplete reporting of outcomes might therefore further increase the true number of fatalities.

- This review is focussed on deaths after chiropractic, yet neck manipulations are, of course, used by other healthcare professionals as well. The reason for this focus is simple: chiropractors are more frequently associated with serious manipulation-related adverse effects than osteopaths, physiotherapists, doctors or other professionals. Of the 40 cases of serious adverse effects mentioned above, 28 can be traced back to a chiropractor and none to a osteopath. A review of complications after spinal manipulations by any type of healthcare professional included three deaths related to osteopaths, nine to medical practitioners, none to a physiotherapist, one to a naturopath and 17 to chiropractors. This article also summarised a total of 265 vascular accidents of which 142 were linked to chiropractors. Another review of complications after neck manipulations published by 1997 included 177 vascular accidents, 32 of which were fatal. The vast majority of these cases were associated with chiropractic and none with physiotherapy. The most obvious explanation for the dominance of chiropractic is that chiropractors routinely employ high-velocity, short-lever thrusts on the upper spine with a rotational element, while the other healthcare professionals use them much more sparingly.

Another review summarised published cases of injuries associated with cervical manipulation in China. A total of 156 cases were found. They included the following problems:

- syncope (45 cases),

- mild spinal cord injury or compression (34 cases),

- nerve root injury (24 cases),

- ineffective treatment/symptom increased (11 cases),

- cervical spine fracture (11 cases),

- dislocation or semi-luxation (6 cases),

- soft tissue injury (3 cases),

- serious accident (22 cases) including paralysis, deaths and cerebrovascular accidents.

Manipulation including rotation was involved in 42% of all cases. In total, 5 patients died…

To sum up … chiropractic SMT can cause a wide range of very serious complications which occasionally can even be fatal. As there is no AE reporting system of such events, we nobody can be sure how frequently they occur.

[references from my text can be found in the book]