evidence

The pandemic has shown how difficult it can be to pass laws stopping healthcare professionals from giving unsound medical advice has proved challenging. The right to freedom of speech regularly conflicts with the duty to protect the public. How can a government best sail between Scylla and Charybdis? JAMA has just published an interesting paper addressing these issues. Here is an excerpt from the article that might stimulate some discussion:

The government can take several actions, including:

- Imposing sanctions on COVID-19–related practices by licensed professionals that flout substantive laws in connection with providing medical services, even if those medical services include speech. This includes physicians failing to comply with COVID-19–related public health laws applicable to medical offices and health facilities, such as mask wearing, social distancing, and restrictions on elective procedures.

- Sanctioning recommendations by professionals that patients take illegal medications or controlled substances without following legally required procedures. The government can also sanction the marketing by others of prescription medications for unapproved indications. However, “off-label” prescribing by physicians (eg, for hydroxychloroquine or ivermectin) remains lawful as long as a medication is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for any indication and no specific legal conditions on use are in effect.

- Enforcing tort law actions (eg, malpractice, lack of informed consent) in cases of alleged patient injury that result from recommending a potentially dangerous treatment or failing to recommend a necessary treatment.

- Imposing sanctions on individualized medical advice by unlicensed individuals or organizations if giving that advice constitutes the unlawful practice of medicine.

In addition, the government probably can:

- Impose sanctions for false or misleading information offered to obtain a financial or personal benefit, particularly if giving the information constitutes fraud under applicable law. This would encompass physicians who knowingly spread false information to create celebrity or attract patients.

- Threaten disciplinary action by licensing boards against health professionals whose speech to patients conveys incorrect science or substandard medicine.

- Specify the information that may and may not be imparted by private organizations and professionals as part of specific clinical services paid for by government, such as special programs for COVID-19 testing or treatment.

- Reject legal challenges to, and enforce through generally applicable contract or employment laws, any restrictions private health care organizations place on speech by affiliated health professionals, particularly in the absence of special laws conferring “conscience” protections. This would include medical staff membership and privileges, hospital or other employment agreements, and insurance network participation.

- Enforce restrictions on speech adopted by private professional or self-regulatory organizations if the consequences for violations are limited to revoking organizational membership or accreditation.

However, the government probably cannot:

- Compel or limit health professional speech not made in connection with patient care, even if the speech is false or misleading, regardless of its alleged effect on public trust in health professions.

- Sanction speech to the general public rather than to patients, whether or not by health professionals, especially if conveyed with a disclaimer that the speech is “not intended as medical advice.”

- Sanction speech by health professionals to patients conveying political views or skepticism of government policy.

- Enforce restrictions involving information by public universities and public hospitals that legislatures, regulatory agencies, and professional licensing boards would not be constitutionally permitted to impose directly.

- Adopt restrictions on information related to overall clinical services funded by large government health programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid.

_____________________________

The article was obviously written with MDs in mind and applies only to US law. As we have seen in previous posts and comments, the debate is, however, wider. We should, I think, also have it in relation to practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and medical ethics. Moreover, it should go beyond advice about COVID and be extended to any medical advice given by any type of healthcare practitioner.

No 10-year follow-up study of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for lumbar intervertebral disc herniation (LDH) has so far been published. Therefore, the authors of this paper performed a prospective 10-year follow-up study on the integrated treatment of LDH in Korea.

One hundred and fifty patients from the baseline study, who initially met the LDH diagnostic criteria with a chief complaint of radiating pain and received integrated treatment, were recruited for this follow-up study. The 10-year follow-up was conducted from February 2018 to March 2018 on pain, disability, satisfaction, quality of life, and changes in a herniated disc, muscles, and fat through magnetic resonance imaging.

Sixty-five patients were included in this follow-up study. Visual analogue scale score for lower back pain and radiating leg pain were maintained at a significantly lower level than the baseline level. Significant improvements in Oswestry disability index and quality of life were consistently present. MRI confirmed that disc herniation size was reduced over the 10-year follow-up. In total, 95.38% of the patients were either “satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with the treatment outcomes and 89.23% of the patients claimed their condition “improved” or “highly improved” at the 10-year follow-up.

The authors concluded that the reduced pain and improved disability was maintained over 10 years in patients with LDH who were treated with nonsurgical Korean medical treatment 10 years ago. Nonsurgical traditional Korean medical treatment for LDH produced beneficial long-term effects, but future large-scale randomized controlled trials for LDH are needed.

This study and its conclusion beg several questions:

WHAT DID THE SCAM CONSIST OF?

The answer is not provided in the paper; instead, the authors refer to 3 previous articles where they claim to have published the treatment schedule:

The treatment package included herbal medicine, acupuncture, bee venom pharmacopuncture and Chuna therapy (Korean spinal manipulation). Treatment was conducted once a week for 24 weeks, except herbal medication which was taken twice daily for 24 weeks; (1) Acupuncture: frequently used acupoints (BL23, BL24, BL25, BL31, BL32, BL33, BL34, BL40, BL60, GB30, GV3 and GV4)10 ,11 and the site of pain were selected and the needles were left in situ for 20 min. Sterilised disposable needles (stainless steel, 0.30×40 mm, Dong Bang Acupuncture Co., Korea) were used; (2) Chuna therapy12 ,13: Chuna is a Korean spinal manipulation that includes high-velocity, low-amplitude thrusts to spinal joints slightly beyond the passive range of motion for spinal mobilisation, and manual force to joints within the passive range; (3) Bee venom pharmacopuncture14: 0.5–1 cc of diluted bee venom solution (saline: bee venom ratio, 1000:1) was injected into 4–5 acupoints around the lumbar spine area to a total amount of 1 cc using disposable injection needles (CPL, 1 cc, 26G×1.5 syringe, Shinchang medical Co., Korea); (4) Herbal medicine was taken twice a day in dry powder (2 g) and water extracted decoction form (120 mL) (Ostericum koreanum, Eucommia ulmoides, Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Achyranthes bidentata, Psoralea corylifolia, Peucedanum japonicum, Cibotium barometz, Lycium chinense, Boschniakia rossica, Cuscuta chinensis and Atractylodes japonica). These herbs were selected from herbs frequently prescribed for LBP (or nerve root pain) treatment in Korean medicine and traditional Chinese medicine,15 and the prescription was further developed through clinical practice at Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine.9 In addition, recent investigations report that compounds of C. barometz inhibit osteoclast formation in vitro16 and A. japonica extracts protect osteoblast cells from oxidative stress.17 E. ulmoides has been reported to have osteoclast inhibitive,18 osteoblast-like cell proliferative and bone mineral density enhancing effects.19 Patients were given instructions by their physician at treatment sessions to remain active and continue with daily activities while not aggravating pre-existing symptoms. Also, ample information about the favourable prognosis and encouragement for non-surgical treatment was given.

The traditional Korean spinal manipulations used (‘Chuna therapy’ – the references provided for it do NOT refer to this specific way of manipulation) seemed interesting, I thought. Here is an explanation from an unrelated paper:

Chuna, which is a traditional manual therapy practiced by Korean medicine doctors, has been applied to various diseases in Korea. Chuna manual therapy (CMT) is a technique that uses the hand, other parts of the doctor’s body or other supplementary devices such as a table to restore the normal function and structure of pathological somatic tissues by mobilization and manipulation. CMT includes various techniques such as thrust, mobilization, distraction of the spine and joints, and soft tissue release. These techniques were developed by combining aspects of Chinese Tuina, chiropratic, and osteopathic medicine.[13] It has been actively growing in Korea, academically and clinically, since the establishment of the Chuna Society (the Korean Society of Chuna Manual Medicine for Spine and Nerves, KSCMM) in 1991.[14] Recently, Chuna has had its effects nationally recognized and was included in the Korean national health insurance in March 2019.[15]

This almost answers the other questions I had. Almost, but not quite. Here are two more:

- The authors conclude that the SCAM produced beneficial long-term effects. But isn’t it much more likely that the outcomes their uncontrolled observations describe are purely or at least mostly a reflection of the natural history of lumbar disc herniation?

- If I remember correctly, I learned a long time ago in medical school that spinal manipulation is contraindicated in lumbar disc herniation. If that is so, the results might have been better, if the patients of this study had not received any SCAM at all. In other words, are the results perhaps due to firstly the natural history of the condition and secondly to the detrimental effects of the SCAM the investigators applied?

If I am correct, this would then be the 4th article reporting the findings of a SCAM intervention that aggravated lumbar disc herniation.

PS

I know that this is a mere hypothesis but it is at least as plausible as the conclusion drawn by the authors.

Low back pain (LBP) is influenced by interrelated biological, psychological, and social factors, however current back pain management is largely dominated by one-size fits all unimodal treatments. Team based models with multiple provider types from complementary professional disciplines is one way of integrating therapies to address patients’ needs more comprehensively.

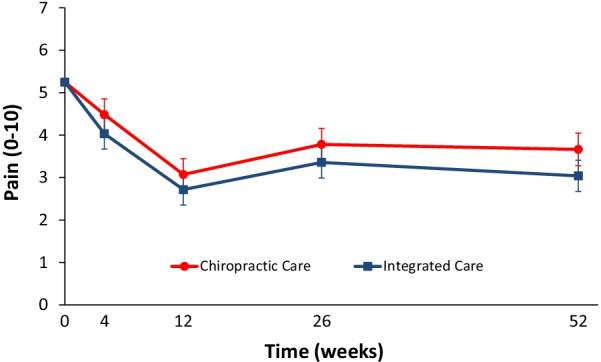

This parallel-group randomized clinical trial conducted from May 2007 to August 2010 aimed to evaluate the relative clinical effectiveness of 12 weeks of monodisciplinary chiropractic care (CC), versus multidisciplinary integrative care (IC), for adults with sub-acute and chronic LBP. The primary outcome was pain intensity and secondary outcomes were disability, improvement, medication use, quality of life, satisfaction, frequency of symptoms, missed work or reduced activities days, fear-avoidance beliefs, self-efficacy, pain coping strategies, and kinesiophobia measured at baseline and 4, 12, 26 and 52 weeks. Linear mixed models were used to analyze outcomes.

In total, 201 participants were enrolled. The largest reductions in pain intensity occurred at the end of treatment and were 43% for CC and 47% for IC. The primary analysis found IC to be significantly superior to CC over the 1-year period (P = 0.02). The long-term profile for pain intensity which included data from weeks 4 through 52, showed a significant advantage of 0.5 for IC over CC (95% CI 0.1 to 0.9; P = 0.02; 0 to 10 scale). The short-term profile (weeks 4 to 12) favored IC by 0.4, but was not statistically significant (95% CI – 0.02 to 0.9; P = 0.06). There was also a significant advantage over the long term for IC in some secondary measures (disability, improvement, satisfaction, and low back symptom frequency), but not for others (medication use, quality of life, leg symptom frequency, fear-avoidance beliefs, self-efficacy, active pain coping, and kinesiophobia). No serious adverse events resulted from either of the interventions.

The authors concluded that participants in the IC group tended to have better outcomes than the CC group, however, the magnitude of the group differences was relatively small. Given the resources required to successfully implement multidisciplinary integrative care teams, they may not be worthwhile, compared to monodisciplinary approaches like chiropractic care, for treating LBP.

The obvious question is: what were the exact treatments used in both groups? The authors provide the following explanations:

All participants in the study received 12 weeks of either monodisciplinary chiropractic care (CC) or multidisciplinary team-based integrative care (IC). CC was delivered by a team of chiropractors allowed to utilize any non-proprietary treatment under their scope of practice not shown to be ineffective or harmful including manual spinal manipulation (i.e., high velocity, low amplitude thrust techniques, with or without the assistance of a drop table) and mobilization (i.e., low velocity, low amplitude thrust techniques, with or without the assistance of a flexion-distraction table). Chiropractors also used hot and cold packs, soft tissue massage, teach and supervise exercise, and administer exercise and self-care education materials at their discretion. IC was delivered by a team of six different provider types: acupuncturists, chiropractors, psychologists, exercise therapists, massage therapists, and primary care physicians, with case managers coordinating care delivery. Interventions included acupuncture and Oriental medicine (AOM), spinal manipulation or mobilization (SMT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), exercise therapy (ET), massage therapy (MT), medication (Med), and self-care education (SCE), provided either alone or in combination and delivered by their respective profession. Participants were asked not to seek any additional treatment for their back pain during the intervention period. Standardized forms were used to document the details of treatment, as well as adverse events. It was not possible to blind patients or providers to treatment due to the nature of the study interventions. Patients in both groups received individualized care developed by clinical care teams unique to each intervention arm. Care team training was conducted to develop and support group dynamics and shared clinical decision making. A clinical care pathway, designed to standardize the process of developing recommendations, guided team-based practitioner in both intervention arms. Evidence based treatment plans were based on patient biopsychosocial profiles derived from the history and clinical examination, as well as baseline patient rated outcomes. The pathway has been fully described elsewhere [23]. Case managers facilitated patient care team meetings, held weekly for each intervention group, to discuss enrolled participants and achieve treatment plan recommendation consensus. Participants in both intervention groups were presented individualized treatment plan options generated by the patient care teams, from which they could choose based on their preferences.

This is undoubtedly an interesting study. It begs many questions. The two that puzzle me most are:

- Why publish the results only 12 years after the trial was concluded? The authors provide a weak explanation, but I would argue that it is unethical to sit on a publicly funded study for so long.

- Why did the researchers not include a third group of patients who were treated by their GP like in normal routine?

The 2nd question is, I think, important because the findings could mostly be a reflection of the natural history of LBP. We can probably all agree that, at present, the optimal treatment for LBP has not been found. To me, the results look as though they indicate that it hardly matters how we treat LBP, the outcome is always very similar. If we throw the maximum amount of care at it, the results tend to be marginally better. But, as the authors admit, there comes a point where we have to ask, is it worth the investment?

Perhaps the old wisdom is not entirely wrong (old because I learned it at medical school some 50 years ago): make sure LBP patients keep as active as they can while trying to ignore their pain as best as they can. It’s not a notion that would make many practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) happy – LBP is their No 1 cash cow! – but it would surely save huge amounts of public expenditure.

Ginseng plants belong to the genus Panax and include:

- Panax ginseng (Korean ginseng),

- Panax notoginseng (South China ginseng),

- and Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng).

They are said to have a range of therapeutic activities, some of which could render ginseng a potential therapy for viral or post-viral infections. Ginseng has therefore been used to treat fatigue in various patient groups and conditions. But does it work for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also often called myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)? This condition is a complex, little-understood, and often disabling chronic illness for which no curative or definitive therapy has yet been identified.

This systematic review aimed to assess the current state of evidence regarding ginseng for CFS. Multiple databases were searched from inception to October 2020. All data was extracted independently and in duplicates. Outcomes of interest included the effectiveness and safety of ginseng in patients with CFS.

A total of two studies enrolling 68 patients were deemed eligible: one randomized clinical trial and one prospective observational study. The certainty of evidence in the effectiveness outcome was low and moderate in both studies, while the safety evidence was very low as reported from one study.

The authors concluded that the study findings highlight a potential benefit of ginseng therapy in the treatment of CFS. However, we are not able to draw firm conclusions due to limited clinical studies. The paucity of data warrants limited confidence. There is a need for future rigorous studies to provide further evidence.

To get a feeling of how good or bad the evidence truly is, we must of course look at the primary studies.

The prospective observational study turns out to be a mere survey of patients using all sorts of treatments. It included 155 subjects who provided information on fatigue and treatments at baseline and follow-up. Of these subjects, 87% were female and 79% were middle-aged. The median duration of fatigue was 6.7 years. The percentage of users who found a treatment helpful was greatest for coenzyme Q10 (69% of 13 subjects), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (65% of 17 subjects), and ginseng (56% of 18 subjects). Treatments at 6 months that predicted subsequent fatigue improvement were vitamins (p = .08), vigorous exercise (p = .09), and yoga (p = .002). Magnesium (p = .002) and support groups (p = .06) were strongly associated with fatigue worsening from 6 months to 2 years. Yoga appeared to be most effective for subjects who did not have unclear thinking associated with fatigue.

The second study investigated the effect of Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) on chronic fatigue (CF) by various measurements and objective indicators. Participants were randomized to KRG or placebo group (1:1 ratio) and visited the hospital every 2 weeks while taking 3 g KRG or placebo for 6 weeks and followed up 4 weeks after the treatment. The fatigue visual analog score (VAS) declined significantly in each group, but there were no significant differences between the groups. The 2 groups also had no significant differences in the secondary outcome measurements and there were no adverse events. Sub-group analysis indicated that patients with initial fatigue VAS below 80 mm and older than 50 years had significantly greater reductions in the fatigue VAS if they used KRG rather than placebo. The authors concluded that KRG did not show absolute anti-fatigue effect but provided the objective evidence of fatigue-related measurement and the therapeutic potential for middle-aged individuals with moderate fatigue.

I am at a loss in comprehending how the authors of the above-named review could speak of evidence for potential benefit. The evidence from the ‘observational study’ is largely irrelevant for deciding on the effectiveness of ginseng, and the second, more rigorous study fails to show that ginseng has an effect.

So, is ginseng a promising treatment for ME?

I doubt it.

Brite is an herbal energy drink that is currently being marketed aggressively. It is even for sale in one leading UK supermarket. It comes in various flavors the ingredients of which vary slightly.

The pineapple/mango drink, for instance, contains:

- guarana extract,

- green tea extract,

- guayusa extract,

- ashwagandha extract,

- matcha tea,

- ascorbic acid (vitamin C),

- natural caffeine.

The website of the manufacturer tells us that Brite uses ingredients and dosages that are safe and effective, utilising the power of nootropic superfoods organic Matcha, Guarana and Guayusa to provide a long-lasting boost.

Brite is based on peer reviewed, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials and studies that can be found here.

It does not tell us the dosages of the ingredients, and I am puzzled by the claim that the drink is safe. A quick search seems to cast considerable doubt on it.

_____________________________

Guarana (Paullinia cupana) is a plant from the Amazon region with a high content of bioactive compounds. It is by no means free of adverse effects. It is known to interact with:

- armodafinil

- caffeine

- dexmethylphenidate

- dextroamphetamine

- green tea

- lisdexamfetamine

- methamphetamine

- methylenedioxymethamphetamine

- methylphenidate

- modafinil

- phentermine

- yohimbine

And it can cause the following adverse effects:

- Abdominal spasms (from overdose)

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Convulsions

- Delirium

- Dependence

- Diarrhea

- Dizziness

- Fast heart rate

- Gastrointestinal (GI) upset

- Headache

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High blood sugar (hyperglycemia)

- Increased respiration

- Increased urination

- Insomnia

- Irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias)

- Irritability

- Muscle spasms

- Nausea/vomiting

- Nervousness

- Painful urination (from overdose)

- Rapid breathing

- Restlessness

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- Stomach cramps or irritation

- Tremors

- Withdrawal symptoms

Green tea is made from the leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant. It can cause the following adverse effects:

- headache,

- nervousness,

- sleep problems,

- vomiting,

- diarrhea,

- irritability,

- irregular heartbeat,

- tremor,

- heartburn,

- dizziness,

- ringing in the ears,

- convulsions,

- confusion.

Guayusa is a plant native to the Amazon rainforest that contains plenty of caffeine. Its adverse effects include:

- High Blood Pressure

- Rapid Heartbeat

- Anxiety

- Jitters

- Energy Crashes

- Insomnia

- Headaches

- Upset Stomach

Ashwagandha is a plant from India; the root and berry are used in Ayurvedic medicine. Its adverse effects include:

- stomach upset,

- diarrhea,

- vomiting.

Matcha tea also contains a high amount of caffeine. It is associated with the following adverse effects:

- nervousness,

- irritability,

- dizziness,

- anxiety,

- digestive disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, or diarrhea,

- sleeping disorders,

- cardiac arrhythmia.

Caffeine is a chemical found in coffee, tea, cola, guarana, mate, and other products. Adverse effects include:

- insomnia,

- nervousness,

- restlessness,

- stomach irritation,

- nausea and vomiting,

- increased heart rate and respiration,

- headache,

- anxiety,

- agitation,

- chest pain,

- ringing in the ears.

A case report documented a case of myocardial infarction in a 25-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with chest pain. The patient had been consuming massive quantities of caffeinated energy drinks daily for the past week. This case report and previously documented studies support a possible connection between caffeinated energy drinks and myocardial infarction.

________________________

Yes, the adverse effects are predominantly (but not exclusively) caused by high doses. Yet, the claim that Brite is safe should nevertheless be taken with a very large pinch of salt. If I like the taste of the drink and thus consume a few bottles per day, the dosages of the ingredients would surely be high!

And what about the claim that it is effective? Here the pinch of salt must be even larger, I am afraid. I could not find a single trial that confirmed the notion. For backing up their claims, the manufacturers offer a few references, but if you look them up, you will find that they were not done with the mixture of ingredients contained in Brite.

So, what is the conclusion?

Based on the evidence that I have seen, the herbal drink ‘Brite’ has not been shown to be an effective nootropic. In addition, there are legitimate concerns about the safety of the product. I for one will therefore not purchase the (rather expensive) drink.

The German Heilpraktiker has been the subject of several of my posts. Some claim that it is an example of a well-established and well-regulated profession. Others insist that it is a menace endangering public health in Germany.

Who is right?

One answer might be found by looking at the training the German Heilpraktiker receives.

In Germany, non-medical practitioners (NMPs; or ‘Heilpraktiker’) offer a broad range of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) methods. The aim of this investigation was to characterize schools for NMPs in Germany in terms of basic (medical) training and advanced education.

The researchers found 165 schools for NMPs in a systematic web-based search. As the medical board examination NMPs must take before building a practice exclusively tests their knowledge in conventional medicine, schools hardly include training in SCAM methods. Only a few schools offered education in SCAM methods in their NMP training. Although NMP associations framed requirements for NMP education, 83.0% (137/165) of schools did not meet these requirements.

The authors concluded that patients and physicians should be aware of the lack of training and consequent risks, such as harm to the body, delay of necessary treatment, and interaction with conventional drugs. Disestablishing the profession of NMPs might be a reasonable step.

Other interesting facts disclosed by this investigation include the following:

- There is no mandatory training for NMPs. Some attend schools but many do not and prefer to learn exclusively from books.

- The training programs of the NMP schools comprise an average of 7.4 hours per week of classroom teaching for an average of 27.1 months.

- Course participants thus complete an average of ~600 hours of training. (A degree in medicine takes an average of 12.9 semesters. With a weekly working time of 38.9 hours, this amounts to ~15,000 hours of training excluding internships etc.)

- Three-quarters of all NMP schools do not offer any practical teaching units.

- If training programs do contain practical instruction, it is usually limited to individual weekend workshops in which the measurement of vital data, physical examinations, and injections and infusions are practiced.

- The exam that NMPs have to pass consists of a written test with sixty multiple-choice questions and a 30 to 60-minute interview on case studies.

- The examination covers professional and legal anatomical and physiological basics, methods of anamnesis and diagnosis, the significance of basic laboratory values as well as practice hygiene and disinfection.

- Not included are competence in pharmacology, pathophysiology, biochemistry, microbiology, human genetics and immunology.

- The average 600 hours of training of an NMP is thus ~5% of that of a medical student.

- If an NMP fails the exam, she can repeat it as often as she needs to pass.

- The day after the exam, an NMP can open her own practice and is allowed (with only very few exceptions) to do most of what proper doctors do.

So are NMPs a danger to public health in Germany?

I let you answer this question yourself.

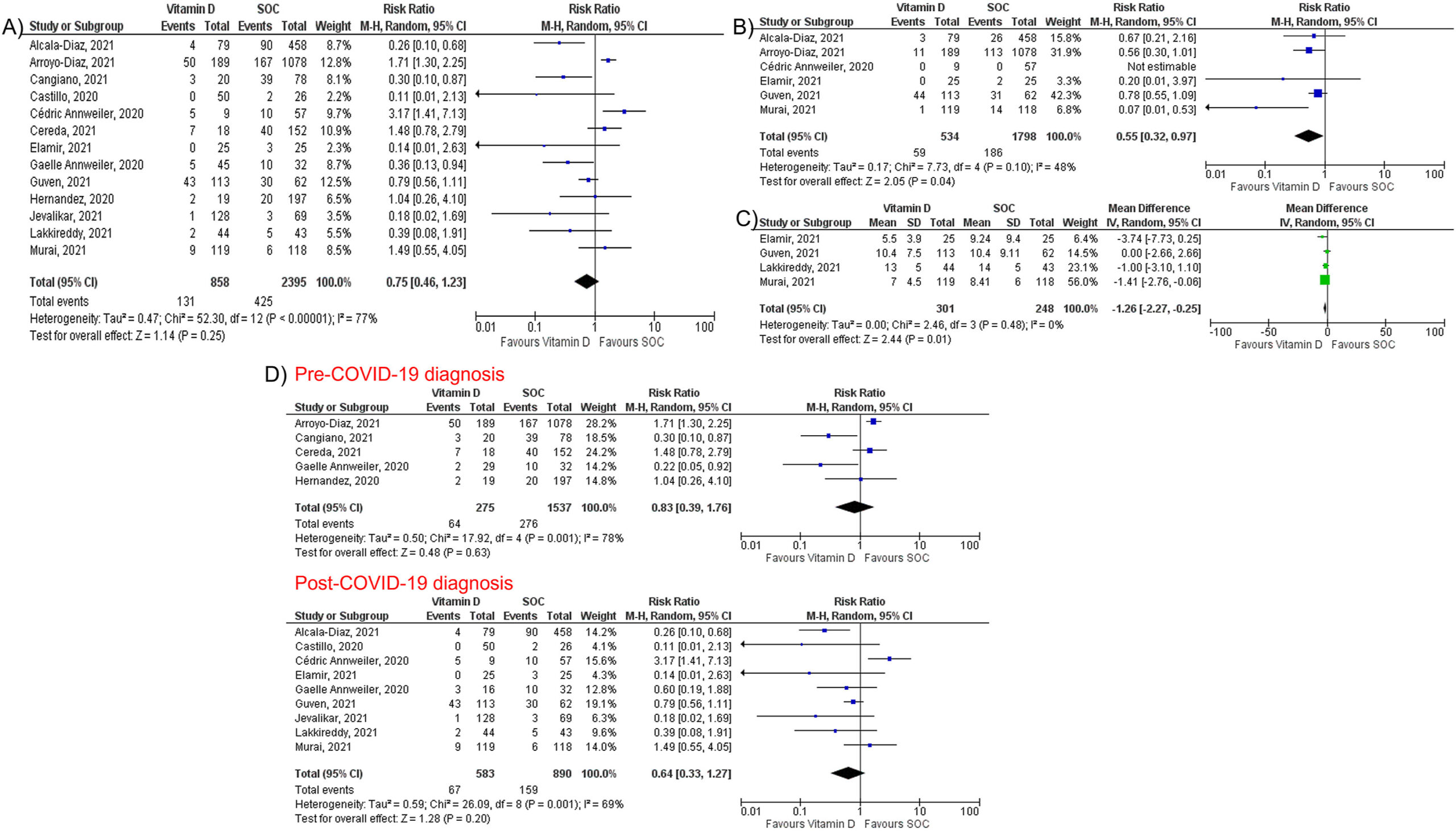

Micronutrient supplements such as vitamin D, vitamin C, and zinc have been used in managing viral illnesses. However, the clinical significance of these individual micronutrients in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains unclear. A team of researchers conducted this meta-analysis to provide a quantitative assessment of the clinical significance of these individual micronutrients in COVID-19.

They performed a literature search using MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane databases through December 5th, 2021. All individual micronutrients reported by ≥ 3 studies and compared with standard-of-care (SOC) were included. The primary outcome was mortality. The secondary outcomes were intubation rate and length of hospital stay (LOS). Pooled risk ratios (RR) and mean difference (MD) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the random-effects model.

The authors identified 26 studies (10 randomized controlled trials and 16 observational studies) involving 5633 COVID-19 patients that compared three individual micronutrient supplements (vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc) with SOC.

Vitamin C

Nine studies evaluated vitamin C in 1488 patients (605 in vitamin C and 883 in SOC). Vitamin C supplementation had no significant effect on mortality (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.62–1.62, P = 1.00), intubation rate (RR 1.77, 95% CI 0.56–5.56, P = 0.33), or LOS (MD 0.64; 95% CI -1.70, 2.99; P = 0.59).

Vitamin D

Fourteen studies assessed the impact of vitamin D on mortality among 3497 patients (927 in vitamin D and 2570 in SOC). Vitamin D did not reduce mortality (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.49–1.17, P = 0.21) but reduced intubation rate (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.32–0.97, P = 0.04) and LOS (MD -1.26; 95% CI -2.27, −0.25; P = 0.01). Subgroup analysis showed that vitamin D supplementation was not associated with a mortality benefit in patients receiving vitamin D pre or post COVID-19 diagnosis.

Zinc

Five studies, including 738 patients, compared zinc intake with SOC (447 in zinc and 291 in SOC). Zinc supplementation was not associated with a significant reduction of mortality (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.60–1.03, P = 0.08).

The authors concluded that individual micronutrient supplementations, including vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc, were not associated with a mortality benefit in COVID-19. Vitamin D may be associated with lower intubation rate and shorter LOS, but vitamin C did not reduce intubation rate or LOS. Further research is needed to validate our findings.

Horticultural therapy (HT)?

What on earth is that?

Don’t worry, it was new to me too and I first thought of the treatment of plants.

HT is said to be a “time-proven practice. The therapeutic benefits of garden environments have been documented since ancient times. In the 19th century, Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and recognized as the “Father of American Psychiatry,” was first to document the positive effect working in the garden had on individuals with mental illness. In the 1940s and 1950s, rehabilitative care of hospitalized war veterans significantly expanded acceptance of the practice. No longer limited to treating mental illness, horticultural therapy practice gained in credibility and was embraced for a much wider range of diagnoses and therapeutic options. Today, horticultural therapy is accepted as a beneficial and effective therapeutic modality. It is widely used within a broad range of rehabilitative, vocational, and community settings. Horticultural therapy techniques are employed to assist participants to learn new skills or regain those that are lost. Horticultural therapy helps improve memory, cognitive abilities, task initiation, language skills, and socialization. In physical rehabilitation, horticultural therapy can help strengthen muscles and improve coordination, balance, and endurance. In vocational horticultural therapy settings, people learn to work independently, problem solve, and follow directions. Horticultural therapists are professionals with specific education, training, and credentials in the use of horticulture for therapy and rehabilitation. Read the formal definition of the role of horticultural therapists.”

As always, the question is DOES IT WORK?

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate HT for general health in older adults. Electronic databases as well as grey literature databases, and clinical trials registers were searched from inception to March 2021. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-RCTs (QRCTs), and cohort studies about HT for adults aged over 60 were included in this review. Outcome measures were physical function, quality of life, BMI, mood tested by self-reported questionnaire and the expression of the immune cells.

Fifteen studies (thirteen RCTs and two cohort studies) involving 1046 older participants were included. Meta-analysis showed that HT resulted in better quality of life (MD 2.09, 95% CI [1.33, 2.85], P<0. 01) and physical function (SMD 0.82, 95% [0.36, 1.29], P<0.01) compared with no-gardener; the similar findings showed in BMI (SMD -0.30, 95% [-0.57, -0.04], P = 0.02) and mood tested by self-reported questionnaire (SMD 2.80, 95% CI [1.82, 3.79], P<0. 01). And HT might be beneficial for blood pressure and immunity, while all the evidence was moderate-quality judged by GRADE.

The authors concluded that HT may improve physical function and quality of life in older adults, reduce BMI and enhance positive mood. A suitable duration of HT may be between 60 to 120 minutes per week lasting 1.5 to 12 months. However, it remains unclear as to what constitutes an optimal recommendation.

I have considerable problems with this review and its conclusion:

- It is simply untrue that there were 13 RCTs; several of these studies were clearly not randomized.

- Most of the studies are of very poor quality. For instance, they often did not make the slightest attempt to control for non-specific effects, yet they concluded that the observed outcome was a specific effect of HT.

My biggest problem does, however, not relate to methodological issues. My main issue with this paper is one of definition. What is a ‘therapy’ and what not? If we call a bit of gardening a ‘therapy’ are we not descending to the level of those who call a bit of shopping ‘retail therapy’? To put it differently, is HT superior to retail therapy? And do we need RCTs to answer this question?

What is wrong with encouraging people who like gardening to just do it? I, for instance, like drumming; but I do not believe we need a few RCTs to prove that it is healthy. Not every past-time or hobby that makes you feel good is a therapy and needs to be scrutinized as such.

It must have been 17 or 18 years ago that I first met Fiona Fox. We were both giving a lecture at the same meeting. My talk was about a small study we did surveying UK homeopaths’ attitudes toward MMR vaccinations. It had landed me in deep waters: some homeopaths had complained and the Exeter ethics committee retrospectively withdrew their approval and forbade me to publish the findings (which were less than flattering for the homeopaths). I told my committee to go yonder and multiply and published our results swiftly. I was then told that I had violated our research ethics and threatened with disciplinary action by my own university.

Fiona seemed to like my stance and realized why I had to do what I did. A little later, she invited me to give a presentation at the ‘Science Media Centre’ (SMC) for journalists about our research. It was then that I realized what the SMC did and how important its work truly was.

At the time, the SMC consisted of a small team of highly motivated people linking scientists with journalists – potentially a win/win situation:

- The scientists would see with their own eyes how important journalists could be for getting their message across.

- And the journalists might comprehend that things were frequently more complex than expected.

Yet, by no means an easy job; scientists are often (sometimes rightly) nervous about speaking to journalists, and journalists sometimes (rightly) feel that scientists are not from the same planet as they are. But if it works out well – and in the SMC it usually does – the beneficiary is the consumer who can read excellent science journalism.

The concept of the SMC was as simple as it was convincing!

No wonder then that it was a monumental success. The SMC grew and so did his influence nationally and internationally. Today, there is hardly a media outlet in the UK that does not regularly refer to the SMC when reporting on matters of science. Much of the outstanding reputation of the SMC is due to the tireless work of Fiona. Her enthusiasm for science is infectious, her energy is impressive, her skills in dealing with experts are immaculate, and her nose for a good story is infallible.

In ‘BEYOND THE HYPE‘, Fiona has now summarized the first 20 eventful years of the SMC. She recounts her favorite moments and some of the biggest science stories that emerged with the help of the SMC. The book is a true page-turner and a ‘must read’ for everyone with an interest in science – entertaining and educational in equal measure. It takes us behind the scenes of some of the most remarkable recent developments in science. Fiona’s book will be out on 7 April; it is a historical document that teaches us important lessons and deserves to be read widely.

I hope that the next 20 years of the SMC will be as good as the first.

A multi-disciplinary research team assessed the effectiveness of interventions for acute and subacute non-specific low back pain (NS-LBP) based on pain and disability outcomes. For this purpose, they conducted a systematic review of the literature with network meta-analysis.

They included all 46 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) involving adults with NS-LBP who experienced pain for less than 6 weeks (acute) or between 6 and 12 weeks (subacute). Non-pharmacological treatments (eg, manual therapy) including acupuncture and dry needling or pharmacological treatments for improving pain and/or reducing disability considering any delivery parameters were included. The comparator had to be an inert treatment encompassing sham/placebo treatment or no treatment. The risk of bias was

- low in 9 trials (19.6%),

- unclear in 20 (43.5%),

- high in 17 (36.9%).

At immediate-term follow-up, for pain decrease, the most efficacious treatments against an inert therapy were:

- exercise (standardised mean difference (SMD) -1.40; 95% confidence interval (CI) -2.41 to -0.40),

- heat wrap (SMD -1.38; 95% CI -2.60 to -0.17),

- opioids (SMD -0.86; 95% CI -1.62 to -0.10),

- manual therapy (SMD -0.72; 95% CI -1.40 to -0.04).

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (SMD -0.53; 95% CI -0.97 to -0.09).

Similar findings were confirmed for disability reduction in non-pharmacological and pharmacological networks, including muscle relaxants (SMD -0.24; 95% CI -0.43 to -0.04). Mild or moderate adverse events were reported in the opioids (65.7%), NSAIDs (54.3%), and steroids (46.9%) trial arms.

The authors concluded that NS-LBP should be managed with non-pharmacological treatments which seem to mitigate pain and disability at immediate-term. Among pharmacological interventions, NSAIDs and muscle relaxants appear to offer the best harm-benefit balance.

The authors point out that previous published systematic reviews on spinal manipulation, exercise, and heat wrap did overlap with theirs: exercise (eg, motor control exercise, McKenzie exercise), heat wrap, and manual therapy (eg, spinal manipulation, mobilization, trigger points or any other technique) were found to reduce pain intensity and disability in adults with acute and subacute phases of NS-LBP.

I would add (as I have done so many times before) that the best approach must be the one that has the most favorable risk/benefit balance. Since spinal manipulation is burdened with considerable harm (as discussed so many times before), exercise and heat wraps seem to be preferable. Or, to put it bluntly: