Monthly Archives: August 2023

The SPECTATOR recently published an article about the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) tendency to push so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Here are a few excerpts from it:

World Health Organisation (WHO) is meant to implore us to ignore hearsay and folklore, and to follow the scientific evidence. So why is it now suddenly promoting the likes of herbal medicine, homeopathy and acupuncture? In a series of tweets this week, the WHO has launched a campaign to extol the virtues of what it calls ‘traditional medicine’. ‘Traditional medicine has been at the frontiers of medicine and science, laying the foundation of conventional medical texts’, it asserts. It goes on to claim that ‘around 40 per cent of approved pharmaceutical products in use today derive from natural substances’ … it then poses the question: ‘which of these have you used: “acupuncture, Ayurveda, herbal medicine, homeopathy, naturopathy, osteopathy, traditional Chinese medicine, unani medicine?”’

… That some folk medicines might sometimes appear to work – in spite of apparently having no active ingredients – is itself explained by scientific inquiry: there is a proven ‘placebo effect’ that causes people to report an improvement in their symptoms as a result of taking something that they think will make them better.

The WHO should be having nothing to do with promoting any medicine which has not been proven without rigorous trials. So why is it suddenly pushing all kinds of dubious cures? It is hard not to see the latest campaign as part of the fashionable campaign to ‘decolonise’ medicine – which means refusing to see western science as superior to belief systems that have derived from elsewhere in the world. The WHO published a podcast on this subject in May, in which a Canadian medical historian, for example, denounced the concept of ‘tropical’ medicine as a construct by colonial powers to try to promote the false idea that the Third World presented a danger to Europe. …

… the WHO has achieved a massive amount by unashamedly exporting rigorous scientific inquiry to parts of the world which it had yet to reach. It wasn’t folk medicine that eradicated smallpox; it was western medicine, and the WHO should not be apologising for that. Promoting quackery seems an odd – and potentially disastrous – direction for the organisation to take.

_____________________________

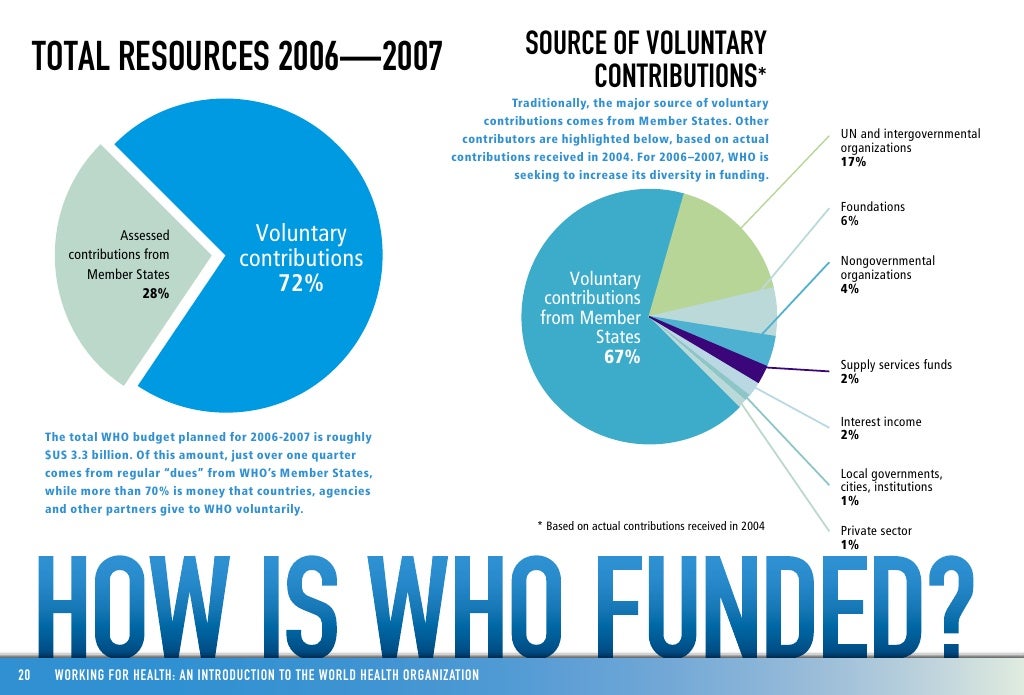

Personally, I concur fully – except for the notion that the WHO started its SCAM-promotion only recently. The truth is that it has done so since many years, and since many years we have on this blog discussed this bizarre trend. In my view, it is a relfection not of the science but of the politics that inflence the WHO to a very large extend in the realm of SCAM.

Manual therapy is considered a safe and less painful method and has been increasingly used to alleviate chronic neck pain. However, there is controversy about the effectiveness of manipulation therapy on chronic neck pain. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aimed to determine the effectiveness of manipulative therapy for chronic neck pain.

A search of the literature was conducted on seven databases (PubMed, Cochrane Center Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, Medline, CNKI, WanFang, and SinoMed) from the establishment of the databases to May 2022. The review included RCTs on chronic neck pain managed with manipulative therapy compared with sham, exercise, and other physical therapies. The retrieved records were independently reviewed by two researchers. Further, the methodological quality was evaluated using the PEDro scale. All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan V.5.3 software. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) assessment was used to evaluate the quality of the study results.

Seventeen RCTs, including 1190 participants, were included in this meta-analysis. Manipulative therapy showed better results regarding pain intensity and neck disability than the control group. Manipulative therapy was shown to relieve pain intensity (SMD = -0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI] = [-1.04 to -0.62]; p < 0.0001) and neck disability (MD = -3.65; 95% CI = [-5.67 to – 1.62]; p = 0.004). However, the studies had high heterogeneity, which could be explained by the type and control interventions. In addition, there were no significant differences in adverse events between the intervention and the control groups.

The authors concluded that manipulative therapy reduces the degree of chronic neck pain and neck disabilities.

Only a few days ago, we discussed another systematic review that drew quite a different conclusion: there was very low certainty evidence supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain.

How can this be?

Systematic reviews are supposed to generate reliable evidence!

How can we explain the contradiction?

There are several differences between the two papers:

- One was published in a SCAM journal and the other one in a mainstream medical journal.

- One was authored by Chinese researchers, the other one by an international team.

- One included 17, the other one 23 RCTs.

- One assessed ‘manual/manipulative therapies’, the other one spinal manipulation/mobilization.

The most profound difference is that the review by the Chinese authors is mostly on Chimese massage [tuina], while the other paper is on chiropractic or osteopathic spinal manipulation/mobilization. A look at the Chinese authors’ affiliation is revealing:

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China.

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

What lesson can we learn from this confusion?

Perhaps that Tuina is effective for neck pain?

No!

What the abstract does not tell us is that the Tuina studies are of such poor quality that the conclusions drawn by the Chinese authors are not justified.

What we do learn – yet again – is that

- Chinese papers need to be taken with a large pintch of salt. In the present case, the searches underpinning the review and the evaluations of the included primary studies were clearly poorly conducted.

- Rubbish journals publish rubbish papers. How could the reviewers and the editors have missed the many flaws of this paper? The answer seems to be that they did not care. SCAM journals tend to publish any nonsense as long as the conclusion is positive.

Vaccine hesitancy has become a threat to public health, especially as it is a phenomenon that has also been observed among healthcare professionals. In this study, an international team of researchers analyzed the relationship between endorsement of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and vaccination attitudes and behaviors among healthcare professionals, using a cross-sectional sample of physicians with vaccination responsibilities from four European countries: Germany, Finland, Portugal, and France (total N = 2,787).

The results suggest that, in all the participating countries, SCAM endorsement is associated with lower frequency of vaccine recommendation, lower self-vaccination rates, and being more open to patients delaying vaccination, with these relationships being mediated by distrust in vaccines. A latent profile analysis revealed that a profile characterized by higher-than-average SCAM endorsement and lower-than-average confidence and recommendation of vaccines occurs, to some degree, among 19% of the total sample, although these percentages varied from one country to another: 23.72% in Germany, 17.83% in France, 9.77% in Finland, and 5.86% in Portugal.

The authors concluded that these results constitute a call to consider health care professionals’ attitudes toward SCAM as a factor that could hinder the implementation of immunization campaigns.

In my view, this is a very important paper. It shows what we on this blog have discussed often before: there is an association between SCAM and vaccination hesitancy. The big question is: what is the nature of this association. There are several possibilities:

- It could be coincidental. I think this is most unlikely; too many entirely different investigations have shown a link.

- It could mean that people start endorsing SCAM because they are critical about vaccination.

- It could be that people are critical about vaccination because they are proponents of SCAM.

- Finally, it could be that some people have a mind-set that renders them simultaneously hesitant about vaccination and fans of SCAM.

This study, like most of the other investigationson this subject, was not desighned to find out which possibility is most likely. I suspect that the latter two explanations apply both to some extend. The authors of this study argue that that, “from a theoretical point of view, this situation may be explicable by reasons that are both implicit (i.e., CAM would fit better with certain worldviews and ideological standpoints that conflict with the epistemology and values that underlies scientific knowledge) and explicit (i.e., some CAM techniques are doctrinally opposed to the use of vaccines). Although we have outlined these potential explanations for the observed relationships, more research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms”.

I like skeptics; they have taught me a lot, and I am thankful for it.

At the same time, they occasionally irritate me when they comment on so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

Why? Because, when they comment on SCAM, they are not rarely wrong or at least not quite correct.

I am referring to the typical scenario where a skeptic discusses a form of SCAM and explains that there is no evidence on it. Such statements are almost invariably false. There is evidence on almost all forms of SCAM; it may not be positive but it exists. To make statements to the contrary is demonstrably wrong.

Let’s assume that a skeptic discusses CUPPING (I am referring to an actual video that I recently watched). He explains its history, how it’s done, that there is no plausible mode of action, and that there is NO evidence on it.

This is not correct!

In fact, there is a substantial body of evidence in terms of clinical trials and even systematic reviews (if you search this blog, you will find quite a bit; if you go on Medline, you’ll find even more). And there is some evidence about cupping’s possible mode of action.

Don’t get me wrong:

- I am not a fan of cupping,

- in fact, cupping is merely an example – I could have chosen almost any other SCAM,

- I am certainly not defending therapists who practice cupping,

- the evidence is far from convincing.

All that I am trying to say is this:

When you comment on a SCAM (or anything else), it is worth checking the evidence. More often than not, you will then find that there is quite a lot of evidence. You might conclude that:

- the evidence is poor quality,

- the evidence is negative,

- the evidence is suspect,

- etc., etc.

So, please comment accordingly. Just saying THERE IS NO EVIDENCE is not just wrong, it is irritating, because it gives the SCAM promoters the occasion to rightly point out that skeptics are just badly informed. And that surely is worth preventing!

This systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) estimated the benefits and harms of cervical spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for treating neck pain. The authors searched the MEDLINE, Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE, CINAHL, PEDro, Chiropractic Literature Index bibliographic databases, and grey literature sources, up to June 6, 2022.

RCTs evaluating SMT compared to guideline-recommended and non-recommended interventions, sham SMT, and no intervention for adults with neck pain were eligible. Pre-specified outcomes included pain, range of motion, disability, health-related quality of life.

A total of 28 RCTs could be included. There was very low to low certainty evidence that SMT was more effective than recommended interventions for improving pain at short-term (standardized mean difference [SMD] 0.66; confidence interval [CI] 0.35 to 0.97) and long-term (SMD 0.73; CI 0.31 to 1.16), and for reducing disability at short-term (SMD 0.95; CI 0.48 to 1.42) and long-term (SMD 0.65; CI 0.23 to 1.06). Only transient side effects were found (e.g., muscle soreness).

The authors concluded that there was very low certainty evidence supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain.

Harms cannot be adequately investigated on the basis of RCT data. Firstly, because much larger sample sizes would be required for this purpose. Secondly, RCTs of spinal manipulation very often omit reporting adverse effects (as discussed repeatedly on this bolg). If we extend our searches beyond RCTs, we find many cases of serious harm caused by neck manipulations (also as discussed repeatedly on this bolg). Therefore, the conclusion of this review should be corrected:

Low certainty evidence exists supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain. The evidence of harm is, however, substantial. It follows that the risk/benefit ratio is not positive. Cervical SMT should therefore be discouraged.

A ‘pragmatic, superiority, open-label, randomised controlled trial’ of sleep restriction therapy versus sleep hygiene has just been published in THE LANCET. Adults with insomnia disorder were recruited from 35 general practices across England and randomly assigned (1:1) using a web-based randomisation programme to either four sessions of nurse-delivered sleep restriction therapy plus a sleep hygiene booklet or a sleep hygiene booklet only. There was no restriction on usual care for either group. Outcomes were assessed at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. The primary endpoint was self-reported insomnia severity at 6 months measured with the insomnia severity index (ISI). The primary analysis included participants according to their allocated group and who contributed at least one outcome measurement. Cost-effectiveness was evaluated from the UK National Health Service and personal social services perspective and expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. The trial was prospectively registered (ISRCTN42499563).

Between Aug 29, 2018, and March 23, 2020 the researchers randomly assigned 642 participants to sleep restriction therapy (n=321) or sleep hygiene (n=321). Mean age was 55·4 years (range 19–88), with 489 (76·2%) participants being female and 153 (23·8%) being male. 580 (90·3%) participants provided data for at least one outcome measurement. At 6 months, mean ISI score was 10·9 (SD 5·5) for sleep restriction therapy and 13·9 (5·2) for sleep hygiene (adjusted mean difference –3·05, 95% CI –3·83 to –2·28; p<0·0001; Cohen’s d –0·74), indicating that participants in the sleep restriction therapy group reported lower insomnia severity than the sleep hygiene group. The incremental cost per QALY gained was £2076, giving a 95·3% probability that treatment was cost-effective at a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000. Eight participants in each group had serious adverse events, none of which were judged to be related to intervention.

The authors concluded that brief nurse-delivered sleep restriction therapy in primary care reduces insomnia symptoms, is likely to be cost-effective, and has the potential to be widely implemented as a first-line treatment for insomnia disorder.

I am frankly amazed that this paper was published in a top journal, like THE LANCET. Let me explain why:

The verum treatment was delivered over four consecutive weeks, involving one brief session per week (two in-person sessions and two sessions over the phone). Session 1 introduced the rationale for sleep restriction therapy alongside a review of sleep diaries, helped participants to select bed and rise times, advised on management of daytime sleepiness (including implications for driving), and discussed barriers to and facilitators of implementation. Session 2, session 3, and session 4 involved reviewing progress, discussion of difficulties with implementation, and titration of the sleep schedule according to a sleep efficiency algorithm.

This means that the verum group received fairly extensive attention, while the control group did not. In other words, a host of non-specific effects are likely to have significantly influenced or even entirely determined the outcome. Despite this rather obvious limitation, the authors fail to discuss any of it. On the contrary, that claim that “we did a definitive test of whether brief sleep restriction therapy delivered in primary care is clinically effective and cost-effective.” This is, in my view, highly misleading and unworthy of THE LANCET. I suggest the conclusions of this trial should be re-formulated as follows:

The brief nurse-delivered sleep restriction, or the additional attention provided exclusively to the patients in the verum group, or a placebo-effect or some other non-specific effect reduced insomnia symptoms.

Alternatively, one could just conclude from this study that poor science can make it even into the best medical journals – a problem only too well known in the realm of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

I was asked by NATURE to provide a comment on the WHO Traditional Medicine Global Summit: Towards health and well-being for all which is about to take place in India:

The First WHO Traditional Medicine Global Summit will take place on 17 and 18 August 2023 in Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India. It will be held alongside the G20 health ministerial meeting, to mobilize political commitment and evidence-based action on traditional medicine, which is a first port of call for millions of people worldwide to address their health and well-being needs.

The Global Summit will be co-hosted by WHO and the Government of India, which holds the presidency of the G20 in 2023. It will be a platform for all stakeholders, including traditional medicine workers, users and communities, national policymakers, international organizations, academics, private sector and civil society organizations, to share best practices and game-changing evidence, data and innovation on the contribution of traditional medicine to health and sustainable development.

For centuries, traditional and complementary medicine has been an integral resource for health in households and communities. It has been at the frontiers of medicine and science laying the foundation for conventional medical texts. Around 40% of pharmaceutical products today have a natural product basis, and landmark drugs derive from traditional medicine, including aspirin, artemisinin, and childhood cancer treatments. New research, including on genomics and artificial intelligence are entering the field, and there are growing industries for herbal medicines, natural products, health, wellness and related travel. Currently, 170 Member States reported to WHO on the use of traditional medicine and have requested evidence and data to inform policies, standards and regulation for its safe, cost-effective and equitable use.

In response to this increased global interest and demand, WHO, with the support of the Government of India, established in March 2022 the WHO Global Centre for Traditional Medicine as a knowledge hub with a mission to catalyse ancient wisdom and modern science for the health and well-being of people and the planet. The WHO Traditional Medicine Centre scales up WHO’s existing capacity in traditional medicine and supplements the core WHO functions of governance, norms and country support carried out across the six regional Offices and Headquarters.

The Centre focuses on partnership, evidence, data, biodiversity and innovation to optimize the contribution of traditional medicine to global health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development, and is also guided by respect for local heritages, resources and rights.

A cross-regional expert panel will advise on the Summit’s theme, format, topics and issues to address. All updates will be posted here and on the forthcoming webpages for the First WHO Traditional Medicine Global Summit.

In case you are interested, the programme can be seen here.

And my comment? I am afraid, it was not very encouraging. I doubt that Nature will publish it in full. So, allow me to show you my unabridged comment:

This article entitled: Keeping Medical Science Trustworthy: The Threat by Predatory Journals caught my attention.

Many scientific journals have started to ask article processes costs from authors. This development has created a new category of journals of which the business model is totally or predominantly based on financial contributions by its authors. Such journals have become known as predatory journals. The financial contributions that they ask are not necessarily lower than those asked by high-quality journals although they offer less:

- there is commonly no real review,

- texts are not edited,

- there are commonly no printed editions.

The lack of serious reviews might make predatory journals attractive particularly to authors of low-quality (or even fraudulent) manuscripts.

The authors of this paper suggest that numerous journals, some of which may predatory, attract manuscripts by approaching authors of articles in high-quality journals. They conclude that publication of articles in such journals contaminates the medical literature and undermines the trustworthiness of science and medicine. Any involvement in such journals (as an author, reviewer or editor) should therefore be discouraged.

The ironic thing here is that the paper was published by a journal that itelf is, in my view, borderline, to say the least. But let me nonetheless contribute a recent, personal experience on this issue.

About 2 weeks ago, I received an invitation to join the editorial board of a general medicine journal that I had never heard of. I looked it up and found that it had a decent impact factor and a long list of international members of the board. But then I found that the journal charged around $ 1 500 for each submission. I was told that this is to cover the cost of the review process.

I then decided to write to the editor thanking her for the kind invitation. I also asked her how much the journal would pay its reviewers for reviewing submissions. I received a polite answer explaining that the amount was $ 00.00. My response was to politely decline the invitation to join the editorial board and to urge the journal editor to make it clear from the outset that the fees charged to authors did NOT go to the reviewers.For many years now, I have taken a very dim view on predatory journals. Sadly, in the realm of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), there currently are dozens of such publications. I believe their danger in polluting the medical literature is hard to over-estimate. I think they ought to be stopped. One way of doing this is refusing to co-operate with them in any way.

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the effectiveness of visceral osteopathy in improving pain intensity, disability and physical function in patients with low-back pain (LBP).

MEDLINE (Pubmed), PEDro, SCOPUS, Cochrane Library and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to February 2022. PICO search strategy was used to identify randomized clinical trials applying visceral techniques in patients with LBP. Eligible studies and data extraction were conducted independently by two reviewers. Quality of the studies was assessed with the Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale, and the risk of bias with Cochrane Collaboration tool. Meta-analyses were conducted using random effects models according to heterogeneity assessed with I2 coefficient. Data on outcomes of interest were extracted by a researcher using RevMan 5.4 software.

Five studies were included in the systematic review involving 268 patients with LBP. The methodological quality of the included ranged from high to low and the risk of bias was high. Visceral osteopathy techniques have shown no improvements in pain intensity (Standardized mean difference (SMD) = -0.53; 95% CI; -1.09, 0.03; I2: 78%), disability (SMD = -0.08; 95% CI; -0.44, 0.27; I2: 0%) and physical function (SMD = -0.26; 95% CI; -0.62, 0.10; I2: 0%) in patients with LBP.

The authors concluded that this systematic review and meta-analysis showed a lack of high-quality studies showing the effectiveness of visceral osteopathy in pain, disability, and physical function in patients with LBP.

Visceral osteopathy (or visceral manipulation) is an expansion of the general principles of osteopathy and involves the manual manipulation by a therapist of internal organs, blood vessels and nerves (the viscera) from outside the body.

Visceral osteopathy was developed by Jean-Piere Barral, a registered Osteopath and Physical Therapist who serves as Director (and faculty) of the Department of Osteopathic Manipulation in Paris, France. He stated that through his clinical work with thousands of patients, he created this modality based on organ-specific fascial mobilization. And through work in a dissection lab, he was able to experiment with visceral manipulation techniques and see the internal effects of the manipulations.[1] According to its proponents, visceral manipulation is based on the specific placement of soft manual forces looking to encourage the normal mobility, tone and motion of the viscera and their connective tissues. These gentle manipulations may potentially improve the functioning of individual organs, the systems the organs function within, and the structural integrity of the entire body.[2] Visceral osteopathy comprises of several different manual techniques firstly for diagnosing a health problem and secondly for treating it.

Several studies have assessed the diagnostic reliability of the techniques involved. The totality of this evidence fails to show that they are sufficiently reliable to be od practical use.[3] Other studies have tested whether the therapeutic techniques used in visceral osteopathy are effective in curing disease or alleviating symptoms. The totality of this evidence fails to show that visceral osteopathy works for any condition.[4]

The treatment itself seems to be safe, yet the risks of visceral osteopathy are nevertheless considerable: if a patient suffers from symptoms related to her inner organs, the therapist is likely to misdiagnose them and subsequently mistreat them. If the symptoms are due to a serious disease, this would amount to medical neglect and could, in extreme cases, cost the patient’s life.

My bottom line: if you see visceral osteopathy being employed anywhere, turn araound and seek proper healthcare whatever your illness might be.

References

[1] https://www.barralinstitute.com/about/jean-pierre-barral.php .

[2] http://www.barralinstitute.co.uk/ .

[3] Guillaud A, Darbois N, Monvoisin R, Pinsault N (2018) Reliability of diagnosis and clinical efficacy of visceral osteopathy: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med 18:65

The increasing demand for fertility treatments has led to the rise of private clinics offering so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) treatments. Even King Charles has recently joined in with this situalion. One of the most frequently offered SCAM infertility treatment is acupuncture. However, there is no good evidence to support the effectiveness of acupuncture in treating infertility.

This study evaluated the scope of information provided by SCAM fertility clinics in the UK. A content analysis was conducted on 200 websites of SCAM fertility clinics in the UK that offer acupuncture as a treatment for infertility. Of the 48 clinics that met the eligibility criteria, the majority of the websites did not provide sufficient information on:

- the efficacy,

- the risks,

- the success rates

of acupuncture for infertility.

The authors concluded that this situation has the potential to infringe on patient autonomy, provide false hope and reduce the chances of pregnancy ever being achieved as fertility declines during the time course of ineffective acupuncture treatment.

The authors are keen to point out that their investigation has certain limitations. The study only analysed the information provided on the clinics’ websites and did not assess the quality of the treatment provided by the clinics.

Therefore, the study’s fndings cannot be generalized to the quality of the acupuncture treatment provided by the clinics.

Nonetheless the paper touches on very important issues: far too many health clinics that offer SCAM for this or that indication operate way outside the ethically (and legally) acceptable norm. They advertise their services without making it clear that they are neither effective nor safe. Desperate consumers thus fall for their promises. In the case of infertility, this might result merely in frustration and loss of (often substantial amounts of) money. In the case of serious disease, such as cancer, this often results in premature death.

It is time, I think, that this entire sector is regualted in a way that it does not endanger the well-being, health, or life of consumers.