survey

The use of and interest in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for animals is often said to be increasing. But only a few reliable data exist on this subject. This survey is based on online research of 1083 German veterinary homepages for contents of veterinary SCAM performed in September and October 2017. “Veterinarian” and “Chamber of Veterinary Surgeons” were used as search items. Homepages of small animal medicine were included. They were surveyed for modes of SCAM treatments and corresponding qualifications of the offering veterinarian.

In total, 60.7 % (n = 657) of homepages showed contents of veterinary SCAM. The highest percentage was found in the Chamber of Veterinary Surgeons of Saarland (91.7 %, n = 11 out of 12). Homeopathy was cited most frequently (58 %, n = 381). Out of all homepages with relevant content, 31.4 % (n = 206) gave information about user qualifications, with continuous education programs named most frequently (52.9 %, n = 109).

The authors concluded that the given data illustrate the high number of German veterinary homepages with contents of veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine, corresponding to actual data of a high usage in veterinary and human medicine. Therefore further scientific research in this field seems reasonable. Modes of treatment and qualifications are highly diverse and despite of controversial public discussions, homeopathy was the most frequently cited treatment modality on German veterinary homepages.

The authors also added this: We like to thank the Karl and Veronica Carstens-Foundation for the postgraduate scholarship.

The little addendum makes it less puzzling, I think, why the paper is almost totally devoid of any critical input. Animals can obviously not give informed consent to medical treatments. Like humans, they need the most effective therapy when ill. It is hard to deny that homeopathy, for instance, does not belong in that category. Thus, veterinary SCAM is confronted with a considerable ethical problem. It is beyond me how an article about SCAM use in animals can not even mention this or other critical issues.

But at least, you might argue, the paper informs us which SCAMs are currently the most popular. Wrong! SCAM use is highly prone to changes in fashion. This paper tells us merely which SCAMs were popular several years ago! The time lag between doing the research and publishing it is something I find all too often in SCAM.

The two authors have recently published another paper. Have a look at this article:

The international use of and interest in veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine are increasing. There are diverse modes of treatment, and owners seem to be well informed. However, there is a lack of data that describes the state of naturopathic or complementary veterinary medicine in Germany. This study aims to address the issue by mapping the currently used treatment modalities, indications, existing qualifications, and information pathways. In order to map the ongoing controversy, this study records the advantages and disadvantages of these medicines as experienced by veterinarians. Demographic influences are investigated to describe distributional impacts on using veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine.

Methods: A standardised questionnaire was used for the cross-sectional survey. It was distributed throughout Germany in a written and digital format from September 2016 to January 2018. Because of the open nature of data collection, the return rate of questionnaires could not be calculated. To establish a feasible timeframe, active data collection stopped when the previously calculated limit of 1061 questionnaires was reached. With the included incoming questionnaires of that day a total of 1087 questionnaires were collected. Completely blank questionnaires and those where participants did not meet the inclusion criteria (were not included, leaving 870 out of 1087 questionnaires to be evaluated. A literature review and the first test run of the questionnaire identified the following treatment modalities: homoeopathy, phytotherapy, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), biophysical treatments, manual treatments, Bach Flower Remedies, neural therapy, homotoxicology, organotherapy, and hirudotherapy which were included in the questionnaire. Categorical items were processed using descriptive statistics in absolute and relative numbers based on the population of completed answers provided for each item. Multiple choices were possible. Metric data were not normally distributed (Shapiro Wilk Test); hence the median, minimum, and maximum were used for description. The impact of demographic data on the implementation of veterinary naturopathy and complementary techniques was calculated using the Mann-Whitney-U-Test for metric data and the exact Fisher-Test for categorical data.

Results: Overall 85.4% (n = 679 of total 795 non-blank data sets) of all the questionnaire participants used naturopathy and complementary medicine. The treatments most commonly used were complex homoeopathy (70.4%, n = 478), phytotherapy (60.2%, n = 409), classic homoeopathy (44.3%, n = 301) and biophysical treatments (40.1%, n = 272). The most common indications were orthopedic (n = 1798), geriatric (n = 1428) and metabolic diseases (n = 1124). Over the last five years, owner demand for naturopathy and complementary treatments was rated as growing by 57.9% of respondents (n = 457 of total 789). Veterinarians most commonly used scientific journals and publications as sources for information about naturopathic and complementary contents (60.8%, n = 479 of total 788). These were followed by advanced training acknowledged by the ATF (Academy for Veterinary Continuing Education, an organisation that certifies independent veterinary continuing education in Germany) (48.6%, n = 383). The current information about naturopathy and complementary medicine was rated as adequate or nearly adequate by a plurality (39.5%, n = 308) of the respondents of this question. Further, 27.7% (n = 216) of participants chose the option that they were not confident to answer this question and 91 answers were left blank. The most commonly named advantages in using veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine were the expansion of treatment modalities (73.5%, n = 566 of total 770), customer satisfaction (70.8%, n = 545) and lower side effects (63.2%, n = 487). The ambiguity of studies, as well as the unclear evidence of mode of action and effectiveness (62.1%, n = 483) and high expectations of owners (50.5%, n = 393) were the disadvantages mentioned most frequently. Classic homoeopathy, in particular, has been named in this context (78.4%, n = 333 of total 425). Age, gender, and type of employment showed a statistically significant impact on the use of naturopathy and complementary medicine by veterinarians (p < 0.001). The university of final graduation showed a weaker but still statistically significant impact (p = 0.027). Users of veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine tended to be older, female, self-employed and a higher percentage of them completed their studies at the University of Berlin. The working environment (rural or urban space) showed no statistical impact on the veterinary naturopathy or complementary medicine profession.

Conclusion: This is the first study to provide German data on the actual use of naturopathy and complementary medicine in small animal science. Despite a potential bias due to voluntary participation, it shows a large number of applications for various indications. Homoeopathy was mentioned most frequently as the treatment option with the most potential disadvantages. However, it is also the most frequently used treatment option in this study. The presented study, despite its restrictions, supports the need for a discussion about evidence, official regulations, and the need for acknowledged qualifications because of the widespread application of veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine. More data regarding the effectiveness and the mode of action is needed to enable veterinarians to provide evidence-based advice to pet owners.

This paper seems at first sight a bit more informative. But it suffers very similar problems: the data were outdated before they were even published, and this article too lacks critical input.

So, what purpose might these two articles serve?

None!

Oh, sorry – they probably did manage to get the doctor’s title for one or two poor vet students who had been hoodwinked with the help of the the Karl and Veronica Carstens-Foundation into conducting some rather useless pieces of research.

It’s again the season for nine lessons, I suppose. So, on the occasion of Christmas Eve, let me rephrase the nine lessons I once gave (with my tongue firmly lodged in my cheek) to those who want to make a pseudo-scientific career in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) research.

- Throw yourself into qualitative research. For instance, focus groups are a safe bet. They are not difficult to do: you gather 5 -10 people, let them express their opinions, record them, extract from the diversity of views what you recognize as your own opinion and call it a ‘common theme’, and write the whole thing up, and – BINGO! – you have a publication. The beauty of this approach is manifold:

-

- you can repeat this exercise ad nauseam until your publication list is of respectable length;

- there are plenty of SCAM journals that will publish your articles;

- you can manipulate your findings at will;

- you will never produce a paper that displeases the likes of King Charles;

- you might even increase your chances of obtaining funding for future research.

- Conduct surveys. They are very popular and highly respected/publishable projects in SCAM. Do not get deterred by the fact that thousands of similar investigations are already available. If, for instance, there already is one describing the SCAM usage by leg-amputated policemen in North Devon, you can conduct a survey of leg-amputated policemen in North Devon with a medical history of diabetes. As long as you conclude that your participants used a lot of SCAMs, were very satisfied with it, did not experience any adverse effects, thought it was value for money, and would recommend it to their neighbour, you have secured another publication in a SCAM journal.

- In case this does not appeal to you, how about taking a sociological, anthropological or psychological approach? How about studying, for example, the differences in worldviews, the different belief systems, the different ways of knowing, the different concepts about illness, the different expectations, the unique spiritual dimensions, the amazing views on holism – all in different cultures, settings or countries? Invariably, you must, of course, conclude that one truth is at least as good as the next. This will make you popular with all the post-modernists who use SCAM as a playground for enlarging their publication lists. This approach also has the advantage to allow you to travel extensively and generally have a good time.

- If, eventually, your boss demands that you start doing what (in his narrow mind) constitutes ‘real science’, do not despair! There are plenty of possibilities to remain true to your pseudo-scientific principles. Study the safety of your favourite SCAM with a survey of its users. You simply evaluate their experiences and opinions regarding adverse effects. But be careful, you are on thin ice here; you don’t want to upset anyone by generating alarming findings. Make sure your sample is small enough for a false negative result, and that all participants are well-pleased with their SCAM. This might be merely a question of selecting your patients wisely. The main thing is that your conclusions do not reveal any risks.

- If your boss insists you tackle the daunting issue of SCAM’s efficacy, you must find patients who happened to have recovered spectacularly well from a life-threatening disease after receiving your favourite form of SCAM. Once you have identified such a person, you detail her experience and publish this as a ‘case report’. It requires a little skill to brush over the fact that the patient also had lots of conventional treatments, or that her diagnosis was never properly verified. As a pseudo-scientist, you will have to learn how to discretely make such details vanish so that, in the final paper, they are no longer recognisable.

- Your boss might eventually point out that case reports are not really very conclusive. The antidote to this argument is simple: you do a large case series along the same lines. Here you can even show off your excellent statistical skills by calculating the statistical significance of the difference between the severity of the condition before the treatment and the one after it. As long as this reveals marked improvements, ignores all the many other factors involved in the outcome and concludes that these changes are the result of the treatment, all should be tickety-boo.

- Your boss might one day insist you conduct what he narrow-mindedly calls a ‘proper’ study; in other words, you might be forced to bite the bullet and learn how to do an RCT. As your particular SCAM is not really effective, this could lead to serious embarrassment in the form of a negative result, something that must be avoided at all costs. I, therefore, recommend you join for a few months a research group that has a proven track record in doing RCTs of utterly useless treatments without ever failing to conclude that it is highly effective. In other words, join a member of my ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME. They will teach you how to incorporate all the right design features into your study without the slightest risk of generating a negative result. A particularly popular solution is to conduct a ‘pragmatic’ trial that never fails to produce anything but cheerfully positive findings.

- But even the most cunningly designed study of your SCAM might one day deliver a negative result. In such a case, I recommend taking your data and running as many different statistical tests as you can find; chances are that one of them will produce something vaguely positive. If even this method fails (and it hardly ever does), you can always focus your paper on the fact that, in your study, not a single patient died. Who would be able to dispute that this is a positive outcome?

- Now that you have grown into an experienced pseudo-scientist who has published several misleading papers, you may want to publish irrefutable evidence of your SCAM. For this purpose run the same RCT over again, and again, and again. Eventually, you want a meta-analysis of all RCTs ever published (see examples here and here). As you are the only person who conducted studies on the SCAM in question, this should be quite easy: you pool the data of all your dodgy trials and, bob’s your uncle: a nice little summary of the totality of the data that shows beyond doubt that your SCAM works and is safe.

Osteopathy is currently regulated in 12 European countries: Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Iceland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Switzerland, and the UK. Other countries such as Belgium and Norway have not fully regulated it. In Austria, osteopathy is not recognized or regulated. The Osteopathic Practitioners Estimates and RAtes (OPERA) project was developed as a Europe-based survey, whereby an updated profile of osteopaths not only provides new data for Austria but also allows comparisons with other European countries.

A voluntary, online-based, closed-ended survey was distributed across Austria in the period between April and August 2020. The original English OPERA questionnaire, composed of 52 questions in seven sections, was translated into German and adapted to the Austrian situation. Recruitment was performed through social media and an e-based campaign.

The survey was completed by 338 individuals (response rate ~26%), of which 239 (71%) were female. The median age of the responders was 40–49 years. Almost all had preliminary healthcare training, mainly in physiotherapy (72%). The majority of respondents were self-employed (88%) and working as sole practitioners (54%). The median number of consultations per week was 21–25 and the majority of respondents scheduled 46–60 minutes for each consultation (69%).

The most commonly used diagnostic techniques were: palpation of position/structure, palpation of tenderness, and visual inspection. The most commonly used treatment techniques were cranial, visceral, and articulatory/mobilization techniques. The majority of patients estimated by respondents consulted an osteopath for musculoskeletal complaints mainly localized in the lumbar and cervical region. Although the majority of respondents experienced a strong osteopathic identity, only a small proportion (17%) advertise themselves exclusively as osteopaths.

The authors concluded that this study represents the first published document to determine the characteristics of the osteopathic practitioners in Austria using large, national data. It provides new information on where, how, and by whom osteopathic care is delivered. The information provided may contribute to the evidence used by stakeholders and policy makers for the future regulation of the profession in Austria.

This paper reveals several findings that are, I think, noteworthy:

- Visceral osteopathy was used often or very often by 84% of the osteopaths.

- Muscle energy techniques were used often or very often by 53% of the osteopaths.

- Techniques applied to the breasts were used by 59% of the osteopaths.

- Vaginal techniques were used by 49% of the osteopaths.

- Rectal techniques were used by 39% of the osteopaths.

- “Taping/kinesiology tape” was used by 40% of osteopaths.

- Applied kinesiology was used by 17% of osteopaths and was by far the most-used diagnostic approach.

Perhaps the most worrying finding of the entire paper is summarized in this sentence: “Informed consent for oral techniques was requested only by 10.4% of respondents, and for genital and rectal techniques by 21.0% and 18.3% respectively.”

I am lost for words!

I fail to understand what meaningful medical purpose the fingers of an osteopath are supposed to have in a patient’s vagina or rectum. Surely, putting them there is a gross violation of medical ethics.

Considering these points, I find it impossible not to conclude that far too many Austrian osteopaths practice treatments that are implausible, unproven, potentially harmful, unethical, and illegal. If patients had the courage to take action, many of these charlatans would probably spend some time in jail.

Earlier this year, I started the ‘WORST PAPER OF 2022 COMPETITION’. As a prize, I am offering the winner (that is the lead author of the winning paper) one of my books that best fits his/her subject. I am sure this will overjoy him or her. I hope to identify about 10 candidates for the prize, and towards the end of the year, I let my readers decide democratically on who should be the winner. In this spirit of democratic voting, let me suggest to you entry No 9. Here is the unadulterated abstract:

Background

With the increasing popularity of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) by the global community, how to teach basic knowledge of TCM to international students and improve the teaching quality are important issues for teachers of TCM. The present study was to analyze the perceptions from both students and teachers on how to improve TCM learning internationally.

Methods

A cross-sectional national survey was conducted at 23 universities/colleges across China. A structured, self-reported on-line questionnaire was administered to 34 Chinese teachers who taught TCM course in English and to 1016 international undergraduates who were enrolled in the TCM course in China between 2017 and 2021.

Results

Thirty-three (97.1%) teachers and 900 (88.6%) undergraduates agreed Chinese culture should be fully integrated into TCM courses. All teachers and 944 (92.9%) undergraduates thought that TCM had important significance in the clinical practice. All teachers and 995 (97.9%) undergraduates agreed that modern research of TCM is valuable. Thirty-three (97.1%) teachers and 959 (94.4%) undergraduates thought comparing traditional medicine in different countries with TCM can help the students better understand TCM. Thirty-two (94.1%) teachers and 962 (94.7%) undergraduates agreed on the use of practical teaching method with case reports. From the perceptions of the undergraduates, the top three beneficial learning styles were practice (34.3%), teacher’s lectures (32.5%), case studies (10.4%). The first choice of learning mode was attending to face-to-face teaching (82.3%). The top three interesting contents were acupuncture (75.5%), Chinese herbal medicine (63.8%), and massage (55.0%).

Conclusion

To improve TCM learning among international undergraduates majoring in conventional medicine, integration of Chinese culture into TCM course, comparison of traditional medicine in different countries with TCM, application of the teaching method with case reports, and emphasization of clinical practice as well as modern research on TCM should be fully considered.

I am impressed with this paper mainly because to me it does not make any sense at all. To be blunt, I find it farcically nonsensical. What precisely? Everything:

- the research question,

- the methodology,

- the conclusion

- the write-up,

- the list of authors and their affiliations: Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, School of Basic Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China, Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Medical College, China Three Gorges University, Yichang, China, Basic Teaching and Research Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, China, Institute of Integrative Medicine, Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China, School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, Department of Chinese Medicine/Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University, Shenyang, China, Department of Acupuncture, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, Teaching and Research Section of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shengli Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medicine University, Jinzhou, China, Department of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China.

- the journal that had this paper peer-reviewed and published.

But what impressed me most with this paper is the way the authors managed to avoid even the slightest hint of critical thinking. They even included a short paragraph in the discussion section where they elaborate on the limitations of their work without ever discussing the true flaws in the conception and execution of this extraordinary example of pseudoscience.

The Sunday Times reported yesterday reported that five NHS trusts currently offer moxibustion to women in childbirth for breech babies, i.e. babies presenting upside down. Moxibustion is a form of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) where mugwort is burned close to acupuncture points. The idea is that this procedure would stimulate the acupuncture point similar to the more common way using needle insertion. The fifth toe is viewed as the best traditional acupuncture point for breech presentation, and the treatment is said to turn the baby in the uterus so that it can be delivered more easily.

At least four NHS trusts are offering acupuncture and reflexology with aromatherapy to help women with delayed pregnancies, while 15 NHS trusts offer hypnobirthing classes. Some women are asked to pay fees of up to £140 for it. These treatments are supposed to relax the mother in the hope that this will speed up the process of childbirth.

The Nice guidelines on maternity care say the NHS should not offer acupuncture, acupressure, or hypnosis unless specifically requested by women. The reason for the Nice warning is simple: there is no convincing evidence that these therapies are effective.

Campaigner Catherine Roy who compiled the list of treatments said: “To one degree or another, the Royal College of Midwives, the Care Quality Commission and parts of the NHS support these pseudoscientific treatments.

“They are seen as innocuous but they carry risks, can delay medical help and participate in an anti-medicalisation stance specific to ‘normal birth’ ideology and maternity care. Nice guidelines are clear that they should not be offered by clinicians for treatment. NHS England must ensure that pseudoscience and non-evidence based treatments are removed from NHS maternity care.”

Birte Harlev-Lam, executive director of the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), said: “We want every woman to have as positive an experience during pregnancy, labour, birth and the postnatal period as possible — and, most importantly, we want that experience to be safe. That is why we recommend all maternity services to follow Nice guidance and for midwives to practise in line with the code set out by the Nursing and Midwifery Council.”

A spokeswoman for Nice said it was reviewing its maternity guidelines. NHS national clinical director for maternity and women’s health, Dr Matthew Jolly, said: “All NHS services are expected to offer safe and personalised clinical care and local NHS areas should commission core maternity services using the latest NICE and clinical guidance. NHS trusts are under no obligation to provide complementary or alternative therapies on top of evidence-based clinical care, but where they do in response to the wishes of mothers it is vital that the highest standards of safety are maintained.”

On this blog, we have repeatedly discussed the strange love affair of midwives with so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), for instance, here. In 2012, we published a summary of 19 surveys on the subject. It showed that the prevalence of SCAM use varied but was often close to 100%. Much of it did not seem to be supported by strong evidence for efficacy. We concluded that most midwives seem to use SCAM. As not all SCAMs are without risks, the issue should be debated openly. Today, there is plenty more evidence to show that the advice of midwives regarding SCAM is not just not evidence-based but also often dangerous. This, of course, begs the question: when will the professional organizations of midwifery do something about it?

This study described osteopathic practise activity, scope of practice and the osteopathic patient profile in order to understand the role osteopathy plays within the United Kingdom’s (UK) health system a decade after the authors’ previous survey.

The researchers used a retrospective questionnaire survey design to ask about osteopathic practice and audit patient case notes. All UK-registered osteopaths were invited to participate in the survey. The survey was conducted using a web-based system. Each participating osteopath was asked about themselves, and their practice and asked to randomly select and extract data from up to 8 random new patient health records during 2018. All patient-related data were anonymized.

The survey response rate was 500 osteopaths (9.4% of the profession) who provided information about 395 patients and 2,215 consultations. Most osteopaths were:

- self-employed (81.1%; 344/424 responses),

- working alone either exclusively or often (63.9%; 237/371),

- able to offer 48.6% of patients an appointment within 3 days (184/379).

Patient ages ranged from 1 month to 96 years (mean 44.7 years, Std Dev. 21.5), of these 58.4% (227/389) were female. Infants <1 years old represented 4.8% (18/379) of patients. The majority of patients presented with musculoskeletal complaints (81.0%; 306/378) followed by pediatric conditions (5%). Persistent complaints (present for more than 12 weeks before the appointment) were the most common (67.9%; 256/377) and 41.7% (156/374) of patients had co-existing medical conditions.

The most common treatment approaches used at the first appointment were:

- soft-tissue techniques (73.9%; 292/395),

- articulatory techniques (69.4%; 274/395),

- high-velocity low-amplitude thrust (34.4%; 136/395),

- cranial techniques (23%).

The mean number of treatments per patient was 7 (mode 4). Osteopaths’ referral to other healthcare practitioners amounted to:

- GPs 29%

- Other complementary therapists 21%

- Other osteopaths 18%

The authors concluded that osteopaths predominantly provide care of musculoskeletal conditions, typically in private practice. To better understand the role of osteopathy in UK health service delivery, the profession needs to do more research with patients in order to understand their needs and their expected outcomes of care, and for this to inform osteopathic practice and education.

What can we conclude from a survey that has a 9% response rate?

Nothing!

If I ignore this fact, do I find anything of interest here?

Not a lot!

Perhaps just three points:

- Osteopaths use high-velocity low-amplitude thrusts, the type of manipulation that has most frequently been associated with serious complications, too frequently.

- They also employ cranial osteopathy, which is probably the least plausible technique in their repertoire, too often.

- They refer patients too frequently to other SCAM practitioners and too rarely to GPs.

To come back to the question asked in the title of this post: What do UK osteopaths do? My answer is

ALMOST NOTHING THAT MIGHT BE USEFUL.

Have you ever wondered how good or bad the education of chiropractors and osteopaths is? Well, I have – and this new paper promises to provide an answer.

The aim of this study was to explore Australian chiropractic and osteopathic new graduates’ readiness for transition to practice concerning their clinical skills, professional behaviors, and interprofessional abilities. Phase 1 explored final-year students’ self-perceptions, and this part uncovered their opinions after 6 months or more in practice.

Interviews were conducted with a self-selecting sample of phase 1 participant graduates from 2 Australian chiropractic and 2 osteopathic programs. Results of the thematic content analysis of responses were compared to the Australian Chiropractic Standards and Osteopathic Capabilities, the authority documents at the time of the study.

Interviews from graduates of 2 chiropractic courses (n = 6) and 2 osteopathic courses (n = 8) revealed that the majority had positive comments about their readiness for practice. Most were satisfied with their level of clinical skills, verbal communication skills, and manual therapy skills. Gaps in competence were identified in written communications such as case notes and referrals to enable interprofessional practice, understanding of professional behaviors, and business skills. These identified gaps suggest that these graduates are not fully cognizant of what it means to manage their business practices in a manner expected of a health professional.

The authors concluded that this small study into clinical training for chiropractic and osteopathy suggests that graduates lack some necessary skills and that it is possible that the ideals and goals for clinical education, to prepare for the transition to practice, may not be fully realized or deliver all the desired prerequisites for graduate practice.

Their conclusions in the actual paper finish with these sentences, in the main, graduate participants and the final year students were unable to articulate what professional behaviors were expected of them. The identified gaps suggest these graduates are not fully cognizant of what it means to manage their business practices in a manner expected of a health professional.

In several ways, this is a remarkable paper – remarkably poor, I hasten to add. Apart from the fact that its sample size was tiny and the response rate was low, it has many further limitations. Most notably, the clinical skills, professional behaviors, and interprofessional abilities were not assessed. All the researchers did was ask the participants how good or bad they were at these skills. Is this method going to generate reliable evidence? I very much doubt it!

Imagine, these guys have just paid tidy sums for their ‘education’ and they have no experience to speak of. Are they going to be in a good position to critically evaluate their abilities? No, I fear not!

Considering these flaws and the fact that chiropractors and osteopaths are not exactly known for their skills of critical thinking, I find it amazing that important deficits in their abilities nevertheless emerge. If I had to formulate a conclusion from all this, I might therefore suggest this:

A dismal study seems to suggest that chiropractic and osteopathic schooling is dismal.

PS

Come to think of it, there might be another fitting option:

Yet another team of chiro- and osteos demonstrate that they don’t know how to do science.

Traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine (TCAM) – as most of my readers know, I prefer the abbreviation SCAM for so-called alternative medicine – refers to a broad range of health practices and products typically not part of the ‘conventional medicine’ system. Its use is substantial among the general population. TCAM products and therapies may be used in addition to, or instead of, conventional medicine approaches, and some have been associated with adverse reactions or other harms.

The aims of this systematic review were to identify and examine recently published national studies globally on the prevalence of TCAM use in the general population, to review the research methods used in these studies, and to propose best practices for future studies exploring the prevalence of use of TCAM.

MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and AMED were searched to identify relevant studies published since 2010. Reports describing the prevalence of TCAM use in a national study among the general population were included. The quality of included studies was assessed using a risk of bias tool developed by Hoy et al. Relevant data were extracted and summarised.

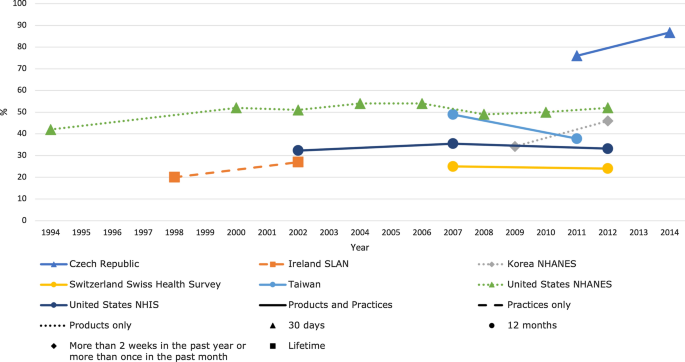

Forty studies from 14 countries, comprising 21 national surveys and one cross-national survey, were included. Studies explored the use of TCAM products (e.g. herbal medicines), TCAM practitioners/therapies, or both. Included studies used different TCAM definitions, prevalence time frames and data collection tools, methods and analyses, thereby limiting comparability across studies. The reported prevalence of use of TCAM (products and/or practitioners/therapies) over the previous 12 months was 24–71.3%.

The authors concluded that the reported prevalence of use of TCAM (products and/or practitioners/therapies) is high, but may underestimate use. Published prevalence data varied considerably, at least in part because studies utilise different data collection tools, methods and operational definitions, limiting cross-study comparisons and study reproducibility. For best practice, comprehensive, detailed data on TCAM exposures are needed, and studies should report an operational definition (including the context of TCAM use, products/practices/therapies included and excluded), publish survey questions and describe the data-coding criteria and analysis approach used.

[Trends in prevalence of TCAM use by country for countries with at least two data collection waves from a nationally representative study. For data collected over several years (e.g. 2007–2009), the prevalence data are plotted at the end of the data collection period (e.g. 2009). Solid and perforated lines between consecutive points are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to represent linearity. NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHIS National Health and Interview Survey, SLAN Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition.]

The review discloses that the prevalence reported across countries ranges from 24 to 71%. This huge variability is not very surprising; some of the many reasons for this phenomenon include:

- different TCAM definitions,

- different prevalence time frames,

- different data collection tools,

- different methods of analyzing the data.

Despite these problems, the information summarized in the review is fascinating in several respects. For me, the most interesting message here is this: the plethora of claims that SCAM use is increasing are not supported by sound evidence.

An article in THE TIMES seems worth mentioning. Here are some excerpts:

… Maternity care at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (NUH) is the subject of an inquiry, prompted by dozens of baby deaths. More than 450 families have now come forward to take part in the review, led by the expert midwife Donna Ockenden. The trust now faces further scrutiny over its use of aromatherapy, after experts branded guidelines at the trust “shocking” and not backed by evidence. Several bereaved families have said they recall aromatherapy being heavily promoted at the trust’s maternity units.

It is being prosecuted over the death of baby Wynter Andrews just 23 minutes after she was born in September 2019. Her mother Sarah Andrews wrote on Twitter that she remembered aromatherapy being seen as “the answer to everything”. Internal guidelines, first highlighted by the maternity commentator Catherine Roy, suggest using essential oils if the placenta does not follow the baby out of the womb quickly enough… the NUH guidelines say aromatherapy can help expel the placenta, and suggest midwives ask women to inhale oils such as clary sage, jasmine, lavender or basil, while applying others as an abdominal compress. They also describe the oils as “extremely effective for the prevention of and, in some cases, the treatment of infection”. The guidelines also suggest essential oils to help women suffering from cystitis, or as a compress on a caesarean section wound. Nice guidelines for those situations do not recommend aromatherapy…

The NUH adds frankincense “may calm hysteria” and is “recommended in situations of maternal panic”. Roy said: “It is shocking that dangerous advice seemed to have been approved by a team of healthcare professionals at NUH. There is a high tolerance for pseudoscience in NHS maternity care … and it needs to stop. Women deserve high quality care, not dangerous quackery.” …

________________________________

The journalist who wrote the article also asked me for a comment, and I emailed her this quote: “Aromatherapy is little more than a bit of pampering; no doubt it is enjoyable but it is not an effective therapy for anything. To use it in medical emergencies seems irresponsible to say the least.” The Times evidently decided not to include my thoughts.

Having now read the article, I checked again and failed to find good evidence for aromatherapy for any of the mentioned conditions. However, I did find an article and an announcement both of which are quite worrying, in my view:

Aromatherapy is often misunderstood and consequently somewhat marginalized. Because of a basic misinterpretation, the integration of aromatherapy into UK hospitals is not moving forward as quickly as it might. Aromatherapy in UK is primarily aimed at enhancing patient care or improving patient satisfaction, and it is frequently mixed with massage. Little focus is given to the real clinical potential, except for a few pockets such as the Micap/South Manchester University initiative which led to a Phase 1 clinical trial into the effects of aromatherapy on infection carried out in the Burns Unit of Wythenshawe Hospital. This article discusses the expansion of aromatherapy within the US and follows 10 years of developing protocols and policies that led to pilot studies on radiation burns, chemo-induced nausea, slow-healing wounds, Alzheimers and end-of-life agitation. The article poses two questions: should nursing take aromatherapy more seriously and do nurses really need 60 hours of massage to use aromatherapy as part of nursing practice?

My own views on aromatherapy are expressed in our now not entirely up-to-date review:

Aromatherapy is the therapeutic use of essential oil from herbs, flowers, and other plants. The aim of this overview was to provide an overview of systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of aromatherapy. We searched 12 electronic databases and our departmental files without restrictions of time or language. The methodological quality of all systematic reviews was evaluated independently by two authors. Of 201 potentially relevant publications, 10 met our inclusion criteria. Most of the systematic reviews were of poor methodological quality. The clinical subject areas were hypertension, depression, anxiety, pain relief, and dementia. For none of the conditions was the evidence convincing. Several SRs of aromatherapy have recently been published. Due to a number of caveats, the evidence is not sufficiently convincing that aromatherapy is an effective therapy for any condition.

In this context, it might also be worth mentioning that we warned about the frequent usage of quackery in midwifery years ago. Here is our systematic review of 2012 published in a leading midwifery journal:

Background: in recent years, several surveys have suggested that many midwives use some form of complementary/alternative therapy (CAT), often without the knowledge of obstetricians.

Objective: to systematically review all surveys of CAT use by midwives.

Search strategy: six electronic databases were searched using text terms and MeSH for CAT and midwifery.

Selection criteria: surveys were included if they reported quantitative data on the prevalence of CAT use by midwives.

Data collection and analysis: full-text articles of all relevant surveys were obtained. Data were extracted according to pre-defined criteria.

Main results: 19 surveys met the inclusion criteria. Most were recent and from the USA. Prevalence data varied but were usually high, often close to 100%. Much use of CATs does not seem to be supported by strong evidence for efficacy.

Conclusion: most midwives seem to use CATs. As not all CATs are without risks, the issue should be debated openly.

I am tired of saying ‘I TOLD YOU SO!’ but nevertheless find it a pity that our warning remained (yet again) unheeded!

The US Food and Drug Administration created the Tainted Dietary Supplement Database in 2007 to identify dietary supplements adulterated with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). This article compared API adulterations in dietary supplements from the 10-year time period of 2007 through 2016 to the most recent 5-year period of 2017 through 2021. Its findings are alarming:

- From 2007 through 2021, 1068 unique products were found to be adulterated with APIs.

- Sexual enhancement and weight-loss dietary supplements are the most common products adulterated with APIs.

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are commonly included in sexual enhancement dietary supplements.

- A single product can include up to 5 APIs.

- Sibutramine, a drug removed from the market due to cardiovascular adverse events, is the most included adulterant API in weight loss products.

- Sibutramine analogues, phenolphthalein (which was removed from the US market because of cancer risk), and fluoxetine were also included.

- Muscle-building dietary supplements were commonly adulterated before 2016, but since 2017 no additional adulterated products have been identified.

The authors concluded that the lack of disclosure of APIs in dietary supplements, circumventing the normal procedure with clinician oversight of prescription drug use, and the use of APIs that are banned by the Food and Drug Administration or used in combinations that were never studied are important health risks for consumers.

The problem of adulterated supplements is by no means new. A similar review published 4 years ago already warned that “active pharmaceuticals continue to be identified in dietary supplements, especially those marketed for sexual enhancement or weight loss, even after FDA warnings. The drug ingredients in these dietary supplements have the potential to cause serious adverse health effects owing to accidental misuse, overuse, or interaction with other medications, underlying health conditions, or other pharmaceuticals within the supplement.”

These papers relate to the US where supplement use is highly prevalent. The harm done by adulterated products is thus huge. If we focus on Chinese or Ayurvedic supplements, the problem might even be more serious. In 2002, my own review concluded that adulteration of Chinese herbal medicines with synthetic drugs is a potentially serious problem which needs to be addressed by adequate regulatory measures. Twenty years later, we seem to be still waiting for effective regulations that protect the consumer.

Progress in medicine, they say, is made funeral by funeral!