clinical trial

This multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled trial was aimed at assessing the long-term efficacy of acupuncture for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). Men with moderate to severe CP/CPPS were recruited, regardless of prior exposure to acupuncture. They received sessions of acupuncture or sham acupuncture over 8 weeks, with a 24-week follow-up after treatment. Real acupuncture treatment was used to create the typical de qi sensation, whereas the sham acupuncture treatment (the authors state they used the Streitberger needle, but the drawing looks more as though they used our device) does not generate this feeling.

The primary outcome was the proportion of responders, defined as participants who achieved a clinically important reduction of at least 6 points from baseline on the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index at weeks 8 and 32. Ascertainment of sustained efficacy required the between-group difference to be statistically significant at both time points.

A total of 440 men (220 in each group) were recruited. At week 8, the proportions of responders were:

- 60.6% (95% CI, 53.7% to 67.1%) in the acupuncture group

- 36.8% (CI, 30.4% to 43.7%) in the sham acupuncture group (adjusted difference, 21.6 percentage points [CI, 12.8 to 30.4 percentage points]; adjusted odds ratio, 2.6 [CI, 1.8 to 4.0]; P < 0.001).

At week 32, the proportions were:

- 61.5% (CI, 54.5% to 68.1%) in the acupuncture group

- 38.3% (CI, 31.7% to 45.4%) in the sham acupuncture group (adjusted difference, 21.1 percentage points [CI, 12.2 to 30.1 percentage points]; adjusted odds ratio, 2.6 [CI, 1.7 to 3.9]; P < 0.001).

Twenty (9.1%) and 14 (6.4%) adverse events were reported in the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups, respectively. No serious adverse events were reported. No significant difference was found in changes in the International Index of Erectile Function 5 score at all assessment time points or in peak and average urinary flow rates at week 8.

The authors concluded that, compared with sham therapy, 20 sessions of acupuncture over 8 weeks resulted in greater improvement in symptoms of moderate to severe CP/CPPS, with durable effects 24 weeks after treatment.

The study was sponsored by the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The trialists originate from the following institutions:

- 1Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China (Y.S., B.L., Z.Q., J.Z., J.W., X.L., W.W., R.P., H.C., X.W., Z.L.).

- 2Key Laboratory of Chinese Internal Medicine of Ministry of Education, Dongzhimen Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China (Y.L.).

- 3ThedaCare Regional Medical Center – Appleton, Appleton, Wisconsin (K.Z.).

- 4Hengyang Hospital Affiliated to Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Hengyang, China (Z.Y.).

- 5The First Hospital of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, China (W.Z.).

- 6Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China (W.F.).

- 7The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, Hefei, China (J.Y.).

- 8West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, China (N.L.).

- 9China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China (L.H.).

- 10Yantai Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Yantai, China (Z.Z.).

- 11Shaanxi Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Xi’an, China (T.S.).

- 12The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China (J.F.).

- 13Beijing Fengtai Hospital of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, Beijing, China (Y.D.).

- 14Xi’an TCM Brain Disease Hospital, Xi’an, China (H.S.).

- 15Dongfang Hospital Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China (H.H.).

- 16Luohu District Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shenzhen, China (H.Z.).

- 17Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guiyang, China (Q.M.).

These facts, together with the previously discussed notion that clinical trials from China are notoriously unreliable, do not inspire confidence. Moreover, one might well wonder about the authors’ claim that patients were blinded. As pointed out above, the real and sham acupuncture were fundamentally different: the former did generate de qi, while the latter did not! A slightly pedantic point is my suspicion that the trial did not test the efficacy but the effectiveness of acupuncture, if I am not mistaken. Finally, one might wonder what the rationale of acupuncture as a treatment of CP/CPPS might be. As far as I can see, there is no plausible mechanism (other than placebo) to explain the effects.

So, is the evidence that emerged from the new study convincing?

No, in my view, it is not!

In fact, I am surprised that a journal as reputable as the Annals of Internal Medicine published it.

Pelargonium sidoides, a traditional medicinal plant native to South Africa, is one of the ornamental geraniums that is thought to be effective in treating URTIs. The plant seems to contain a large variety of phytochemicals, including amino acids, phenolic acids, α-hydroxy-acids, vitamins, polyphenols, flavonoids, coumarins, coumarins glucosides, coumarin sulphates and nucleotides. It is mostly used to treat the symptoms of acute bronchitis, common cold and acute rhinosinusitis.

The present study aimed to assess the effectiveness of the liquid herbal drug preparation from the root extracts of Pelargonium sidoides in improving symptoms of uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). One hundred sixty-four patients with URTI were randomized and given either verum containing the root extracts of Pelargonium sidoides (n = 82) or a matching placebo (n = 82) in a single-blind manner for 7 days. The median total scores of all symptoms (TSS) showed a significant decreasing trend in the group treated with the root extracts derived from Pelargonium sidoides compared to the placebo group from day 0 to day 7 (TSS significantly decreased by 0.85 points in the root extract group compared to a decrease of 0.62 points, p = 0.018). “Cough frequency” showed a significant improvement from day 0 to day 3 (p = 0.023). There was also detected a significant recovery in “sneezing” on day 3 via Brunner-Langer model, and it was detected that the extract administration given in the first 24 h onset of the symptoms had provided a significant improvement in day 0 to day 3 (difference of TSS 0.18 point, p = 0.011).

The authors concluded that Pelargonium sidoides extracts are effective in relieving the symptom burden in the duration of the disease. It may be regarded as an alternative option for the management of URTIs.

These findings are less surprising than they may seem. Already in 2008, we published the following systematic review:

Objective: To critically assess the efficacy of Pelargonium sidoides for treating acute bronchitis.

Data sources: Systematic literature searches were performed in 5 electronic databases: (Medline (1950 – July 2007), Amed (1985 – July 2007), Embase (1974 – July 2007), CINAHL (1982 – July 2007), and The Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 2007) without language restrictions. Reference lists of retrieved articles were searched, and manufacturers contacted for published and unpublished materials.

Review methods: Study selection was done according to predefined criteria. All randomized clinical trials (RCTs) testing P. sidoides extracts (mono preparations) against placebo or standard treatment in patients with acute bronchitis and assessing clinically relevant outcomes were included. Two reviewers independently selected studies, extracted and validated relevant data. Methodological quality was evaluated using the Jadad score. Meta-analysis was performed using a fixed-effect model for continuous data, reported as weighted mean difference with 95% confidence intervals.

Results: Six RCTs met the inclusion criteria, of which 4 were suitable for statistical pooling. Methodological quality of most trials was good. One study compared an extract of P. sidoides, EPs 7630, against conventional non-antibiotic treatment (acetylcysteine); the other five studies tested EPs 7630 against placebo. All RCTs reported findings suggesting the effectiveness of P. sidoides in treating acute bronchitis. Meta-analysis of the four placebo-controlled RCTs suggested that EPs 7630 significantly reduced bronchitis symptom scores in patients with acute bronchitis by day 7. No serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusion: There is encouraging evidence from currently available data that P. sidoides is effective compared to placebo for patients with acute bronchitis.

Meanwhile, P.sidoides has been associated with liver damage, a fact that might dampen our enthusiasm for this remedy. Nevertheless, it seems to me that this plant merits further study.

This overview was aimed at critically appraising the best available systematic review (SR) evidence on the health

effects of Tai Chi. Nine databases (English and Chinese languages) were searched for SRs of controlled clinical trials of Tai Chi interventions published between Jan-2010 and Dec-2020 in any language. Excluded were primary studies and meta-analyses that combined Tai Chi with other interventions. To minimize overlap, effect estimates were extracted from the most recent, comprehensive, highest quality SR for each population, condition, and outcome. SR quality was appraised using AMSTAR 2 and effect estimates with GRADE.

Of the 210 included SRs, 193 only included randomized controlled trials, one only included non-randomized

studies of interventions, and 16 included both. The most common conditions were neurological (18.6%), falls/balance (14.7%), cardiovascular (14.7%), musculoskeletal (11.0%), cancer (7.1%) and diabetes mellitus (6.7%). Except for stroke, no evidence for disease prevention was found, instead, proxy-outcomes/risks factors were evaluated. 114 effect estimates were extracted from 37 SRs (2 high quality, 6 moderate, 18 low, and 11 critically low), representing 59,306 adults. Compared to active and/or inactive controls, a clinically important benefit from Tai Chi was reported for 66 effect estimates; 53 reported an equivalent or marginal benefit, and 6 had an equivalent risk of adverse events. Eight effect estimates (7.0%) were graded as high certainty evidence, 43 (37.7%) moderate, 36 (31.6%) low, and 27 (23.7%) very low. This was due to concerns with risk of bias in 92 (80.7%) effect estimates, imprecision in 43 (37.7%), inconsistency in 37 (32.5%), and publication bias in 3 (2.6%). SR quality was limited by the search strategies, language bias, inadequate consideration of clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity, poor reporting standards, and/or no registered protocol.

The authors concluded that the findings suggest Tai Chi has multisystem effects with physical, psychological, and quality of life benefits for a wide range of conditions, including individuals with multiple health problems. Clinically important benefits were most consistently reported for Parkinson’s disease, falls risk, knee osteoarthritis, low back pain, cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, and stroke. Notwithstanding, for most conditions, higher quality primary studies and SRs are required.

The authors start the discussion section by stating: This critical overview comprehensively identified SRs of Tai Chi published in English, Chinese and Korean languages that evaluated the effectiveness and safety of Tai Chi for health promotion, and disease prevention and management.

I must say that I do not find the overview all that ,critical’. The authors admit that the primary studies often lacked scientific rigor. Yet they draw firm positive conclusions from the data. I think that this is wrong.

Most of the authors of this overview come from Chinese institutions dedicated to promoting TCM. Yet there is no declaration that this fact might constitute a conflict of interest.

I also miss critical comments on two important questions:

- Are the positive effects of Tai chi superior to conventional treatments of the respective conditions?

- Are the effects of Tai chi really due to the treatment per see or might they be largely caused by context effects (which, considering the nature of the therapy, might be substantial)?

Chinese researchers evaluated the effect of Chinese medicine (CM) on survival time and quality of life (QoL) in patients with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). They conducted an exploratory and prospective clinical observation. Patients diagnosed with SCLC receiving CM treatment as an add-on to conventional cancer therapies were included and followed up every 3 months. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS), and the secondary outcomes were progression-free survival (PFS) and QoL.

A total of 136 patients including 65 limited-stage SCLC (LS-SCLC) patients and 71 extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC) patients were analyzed. The median OS of ES-SCLC patients was 17.27 months, and the median OS of LS-SCLC was 40.07 months. The survival time was 16.27 months for SCLC patients with brain metastasis, 9.83 months for liver metastasis, 13.43 months for bone metastasis, and 18.13 months for lung metastasis. Advanced age, pleural fluid, liver, and brain metastasis were risk factors, while longer CM treatment duration was a protective factor. QoL assessment indicated that after 6 months of CM treatment, scores increased in function domains and decreased in symptom domains.

The authors concluded that CM treatment might help prolong OS of SCLC patients. Moreover, CM treatment brought the trend of symptom amelioration and QoL improvement. These results provide preliminary evidence for applying CM in SCLC multi-disciplinary treatment.

Sorry, but these results provide NO evidence for applying CM in SCLC multi-disciplinary treatment! Even if the findings were a bit better than those reported for SCLC in the literature – and I am not sure they are – it is simply not possible to say with any degree of certainty what effect the CM had. For that, we would obviously need a proper control group.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81673797), and Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. 7182142). In my view, this paper is an example for showing how the relentless promotion of dubious Traditional Chinese Medicine by Chinese officials might cost lives.

I feel that it is time to do something about it.

But what precisely?

Any ideas anyone?

Myofascial release (also known as myofascial therapy or myofascial trigger point therapy) is a type of low-load stretch therapy that is said to release tightness and pain throughout the body caused by the myofascial pain syndrome, a chronic muscle pain that is worse in certain areas known as trigger points. Various types of health professionals provide myofascial release, e.g. osteopaths, chiropractors, physical or occupational therapists, massage therapists, or sports medicine/injury specialists. The treatment is usually applied repeatedly, but there is also a belief that a single session of myofascial release is effective. This study was a crossover clinical trial aimed to test whether a single session of a specific myofascial release technique reduces pain and disability in subjects with chronic low back pain (CLBP).

A total of 41 participants were randomly enrolled into 3 situations in a balanced and crossover manner:

- experimental,

- placebo,

- control.

The subjects underwent a single session of myofascial release on thoracolumbar fascia and the results were compared with the control and placebo groups. A single trained and experienced therapist applied the technique.

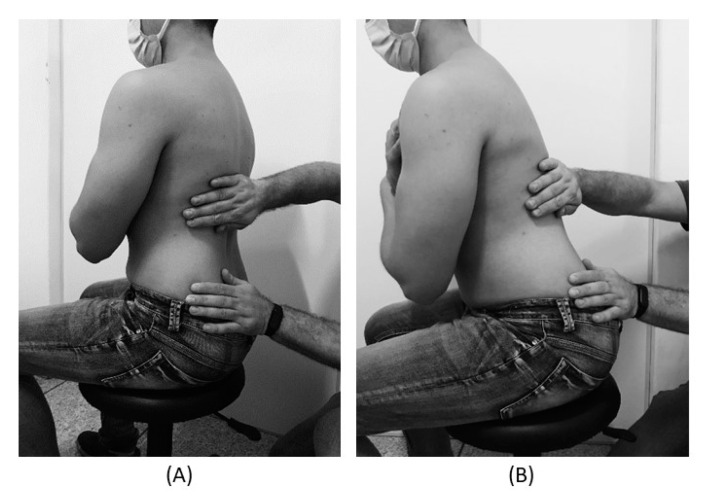

For the control treatment, the subjects were instructed to remain in the supine position for 5 minutes. For the muscle release session, the subjects were in a sitting position with feet supported and the thoracolumbar region properly undressed. The trunk flexion goniometry of each participant was performed and the value of 30° was marked with a barrier to limit the necessary movement during the technique. The trained researcher positioned their hands on all participants without sliding over the skin or forcing the tissue, with the cranial hand close to the last rib and at the T12–L1 level on the right side of the individual’s body and the caudal hand on the ipsilateral side between the iliac crest and the sacrum. Then, the researcher caused slight traction in the tissues by moving their hands away from each other in a longitudinal direction. Then, the participant was instructed to perform five repetitions of active trunk flexion-extension (30°), while the researcher followed the movement with both hands simultaneously positioned, without losing the initial tissue traction and position. The same technique and the same number of repetitions of active trunk flexion-extension were repeated with the researcher’s hands positioned on the opposite sides. This technique lasted approximately five minutes.

For the placebo treatment, the subjects were not submitted to the technique of manual thoracolumbar fascia release, but they slowly performed ten repetitions of active trunk flexion-extension (30°) in the same position as the experimental situation. Due to the fact that touch can provide not only well-recognized discriminative input to the brain, but also an affective input, there was no touch from the researcher at this stage.

The outcomes, pain, and functionality, were evaluated using the numerical pain rating scale (NPRS), pressure pain threshold (PPT), and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).

The results showed no effects between-tests, within-tests, nor for interaction of all the outcomes, i.e., NPRS (η 2 = 0.32, F = 0.48, p = 0.61), PPT (η2 = 0.73, F = 2.80, p = 0.06), ODI (η2 = 0.02, F = 0.02, p = 0.97).

The authors concluded that a single trial of a thoracolumbar myofascial release technique was not enough to reduce pain intensity and disability in subjects with CLBP.

Surprised?

I’m not!

Recently, I received this comment from a reader:

Edzard-‘I see you do not understand much of trial design’ is true BUT I wager that you are in the same boat when it comes to a design of a trial for LBP treatment: not only you but many other therapists. There are too many variables in the treatment relationship that would allow genuine , valid criticism of any design. If I have to pick one book of the several listed elsewhere I choose Gregory Grieve’s ‘Common Vertebral Joint Problems’. Get it, read it, think about it and with sufficient luck you may come to realize that your warranted prejudices against many unconventional ‘medical’ treatments should not be of the same strength when it comes to judging the physical therapy of some spinal problems as described in the book.

And a chiro added:

EE: I see that you do not understand much of trial design

Perhaps it’s Ernst who doesnt understand how to research back pain.

“The identification of patient subgroups that respond best to specific interventions has been set as a key priority in LBP research for the past 2 decades.2,7 In parallel, surveys of clinicians managing LBP show that there are strong views against generic treatment and an expectation that treatment should be individualized to the patient.6,22.”

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy

Published Online:January 31, 2017Volume47Issue2Pages44-48

Do I need to explain why the Grieve book (yes, I have it and yes, I read it) is not a substitute for evidence that an intervention or technique is effective? No, I didn’t think so. This needs to come from a decent clinical trial.

And how would one design a trial of LBP (low back pain) that would be a meaningful first step and account for the “many variables in the treatment relationship”?

How about proceeding as follows (the steps are not necessarily in that order):

- Study the previously published literature.

- Talk to other experts.

- Recruit a research team that covers all the expertise you need (and don’t have yourself).

- Formulate your research question. Mine would be IS THERAPY XY MORE EFFECTIVE THAN USUAL CARE FOR CHRONIC LBP? I know LBP is but a vague symptom. This does, however, not necessarily matter (see below).

- Define primary and secondary outcome measures, e.g. pain, QoL, function, as well as the validated methods with which they will be quantified.

- Clarify the method you employ for monitoring adverse effects.

- Do a small pilot study.

- Involve a statistician.

- Calculate the required sample size of your study.

- Consider going multi-center with your trial if you are short of patients.

- Define chronic LBP as closely as you can. If there is evidence that a certain type of patient responds better to the therapy xy than others, that might be considered in the definition of the type of LBP.

- List all inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Make sure you include randomization in the design.

- Randomization should be to groups A and B. Group A receives treatment xy, while group B receives usual care.

- Write down what A and B should and should not entail.

- Make sure you include blinding of the outcome assessors and data evaluators.

- Define how frequently the treatments should be administered and for how long.

- Make sure all therapists employed in the study are of a high standard and define the criteria of this standard.

- Train all therapists of both groups such that they provide treatments that are as uniform as possible.

- Work out a reasonable statistical plan for evaluating the results.

- Write all this down in a protocol.

Such a trial design does not need patient or therapist blinding nor does it require a placebo. The information it would provide is, of course, limited in several ways. Yet it would be a rigorous test of the research question.

If the results of the study are positive, one might consider thinking of an adequate sham treatment to match therapy xy and of other ways of firming up the evidence.

As LBP is not a disease but a symptom, the study does not aim to include patients that all are equal in all aspects of their condition. If some patients turn out to respond better than others, one can later check whether they have identifiable characteristics. Subsequently, one would need to do a trial to test whether the assumption is true.

Therapy xy is complex and needs to be tailored to the characteristics of each patient? That is not necessarily an unsolvable problem. Within limits, it is possible to allow each therapist the freedom to chose the approach he/she thinks is optimal. If the freedom needed is considerable, this might change the research question to something like ‘IS THAT TYPE OF THERAPIST MORE EFFECTIVE THAN THOSE EMPLOYING USUAL CARE FOR CHRONIC LBP?’

My trial would obviously not answer all the open questions. Yet it would be a reasonable start for evaluating a therapy that has not yet been submitted to clinical trials. Subsequent trials could build on its results.

I am sure that I have forgotten lots of details. If they come up in discussion, I can try to incorporate them into the study design.

Acupuncture is a veritable panacea; it cures everything! At least this is what many of its advocates want us to believe. Does it also have a role in supportive cancer care?

Let’s find out.

This systematic review evaluated the effects of acupuncture in women with breast cancer (BC), focusing on patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

A comprehensive literature search was carried out for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting PROs in BC patients with treatment-related symptoms after undergoing acupuncture for at least four weeks. Literature screening, data extraction, and risk bias assessment were independently carried out by two researchers. The authors stated that they followed the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) guidelines.

Out of the 2, 524 identified studies, 29 studies representing 33 articles were included in this meta-analysis. The RCTs employed various acupuncture techniques with a needle, such as hand-acupuncture and electroacupuncture. Sham/placebo acupuncture, pharmacotherapy, no intervention, or usual care were the control interventions. About half of the studies lacked adequate blinding.

At the end of treatment (EOT), the acupuncture patients’ quality of life (QoL) was measured by the QLQ-C30 QoL subscale, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endocrine Symptoms (FACT-ES), the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General/Breast (FACT-G/B), and the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MENQOL), which depicted a significant improvement. The use of acupuncture in BC patients lead to a considerable reduction in the scores of all subscales of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) measuring pain. Moreover, patients treated with acupuncture were more likely to experience improvements in hot flashes scores, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and anxiety compared to those in the control group, while the improvements in depression were comparable across both groups. Long-term follow-up results were similar to the EOT results. Eleven RCTs did not report any information on adverse effects.

The authors concluded that current evidence suggests that acupuncture might improve BC treatment-related symptoms measured with PROs including QoL, pain, fatigue, hot flashes, sleep disturbance and anxiety. However, a number of included studies report limited amounts of certain subgroup settings, thus more rigorous, well-designed and larger RCTs are needed to confirm our results.

This review looks rigorous on the surface but has many weaknesses if one digs only a little deeper. To start with, it has no precise research question: is any type of acupuncture better than any type of control? This is not a research question that anyone can answer with just a few studies of mostly poor quality. The authors claim to follow the PRISMA guidelines, yet (as a co-author of these guidelines) I can assure you that this is not true. Many of the included studies are small and lacked blinding. The results are confusing, contradictory and not clearly reported. Many trials fail to mention adverse effects and thus violate research ethics, etc., etc.

The conclusion that acupuncture might improve BC treatment-related symptoms could be true. But does this paper convince me that acupuncture DOES improve these symptoms?

No!

Withania somnifera, commonly known as Ashwagandha, is a plant belonging to the family of Solanaceae. It is widely used in Ayurvedic medicine. The plant is promoted as an immunomodulator, anti-inflammatory, anti-stress, anti-Parkinson, anti-Alzheimer, cardioprotective, neural and physical health enhancer, neuro-defensive, anti-diabetic, aphrodisiac, memory-boosting, and ant-cancer remedy. It contains diverse phytoconstituents including alkaloids, steroids, flavonoids, phenolics, nitrogen-containing compounds, and trace elements.

But how much of the hype is supported by evidence? Unsurprisingly, there is a shortage of good clinical trials. Yet, during the last few years, a surprising number of reviews of the accumulating evidence have emerged:

- One review suggested that pre-clinical, as well as clinical studies, suggest the effectiveness of Withania somnifera (L.) against neurodegenerative disease.

- A further review suggested a potential role of W. somnifera in managing diabetes.

- A systematic review of 5 clinical trials found that W. somnifera extract improved performance on cognitive tasks, executive function, attention, and reaction time. It also appears to be well tolerated, with good adherence and minimal side effects.

- Another systematic review included 4 clinical trials and reported significant improvements in serum hormonal profile, oxidative biomarkers, and antioxidant vitamins in seminal plasma. No adverse effects were reported in infertile men taking W. somnifera treatment.

- Another review concluded that the root of the Ayurvedic drug W. somnifera (Aswagandha) appears to be a promising safe and effective traditional medicine for management of schizophrenia, chronic stress, insomnia, anxiety, memory/cognitive enhancement, obsessive-compulsive disorder, rheumatoid arthritis, type-2 diabetes and male infertility, and bears fertility promotion activity in females adaptogenic, growth promoter activity in children and as adjuvant for reduction of fatigue and improvement in quality of life among cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

- A systematic review of 13 RCTs found that Ashwagandha supplementation was more efficacious than placebo for improving variables related to physical performance in healthy men and women.

- Another systematic review concluded that Ashwagandha supplementation might improve the VO2max in athletes and non-athletes.

Impressed?

This certainly looks as though that this plant is worthy of further study. But I can never help feeling a bit skeptical when I hear of such a multitude of benefits without evidence for adverse effects (other than minor upset stomach, nausea, and drowsiness).

While working on yesterday’s post, I discovered another recent and remarkable article co-authored by Prof Harald Walach. It would surely be unforgivable not to show you the abstract:

The aim of this study is to explore experiences and perceived effects of the Rosary on issues around health and well-being, as well as on spirituality and religiosity. A qualitative study was conducted interviewing ten Roman Catholic German adults who regularly practiced the Rosary prayer. As a result of using a tangible prayer cord and from the rhythmic repetition of prayers, the participants described experiencing stability, peace and a contemplative connection with the Divine, with Mary as a guide and mediator before God. Praying the Rosary was described as helpful in coping with critical life events and in fostering an attitude of acceptance, humbleness and devotion.

The article impressed me so much that it prompted me to design a virtual study for which I borrowed Walach’s abstract. Here it is:

The aim of this study is to explore experiences and perceived effects of train-spotting on issues around health and well-being, as well as on spirituality. A qualitative study was conducted interviewing ten British adults who regularly practiced the art of train-spotting. As a result of using a tangible train-spotter diary and from the rhythmic repetition of the passing trains, the participants described experiencing stability, peace, and a contemplative connection with the Divine, with Mary as a guide and mediator before the almighty train-spotter in the sky. Train-spotting was described as helpful in coping with critical life events and in fostering an attitude of acceptance, humbleness, and devotion.

These virtual results are encouraging and encourage me to propose the hypothesis that Rosary use and train-spotting might be combined to create a new wellness program generating a maximum holistic effect. We are grateful to Walach et al for the inspiration and are currently applying for research funds to test our hypothesis in a controlled clinical trial.

Homeopathy is sometimes claimed to be effective for primary dysmenorrhoea (PD), but the claim is not supported by sound evidence. This study was undertaken to examine the efficacy of individualized homeopathic medicines (IH) against placebo in the treatment of PD.

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at the gynecology outpatient department of Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, West Bengal, India. Patients were randomized to receive either IH (n=64) or identical-looking placebo (n=64). Primary and secondary outcome measures were 0-10 numeric rating scales (NRS) measuring the intensity of pain of dysmenorrhea and verbal multidimensional scoring system (VMSS) respectively, all measured at baseline, and every month, up to 3 months.

The two groups were comparable at baseline. The attrition rate was 10.9% (IH: 7, placebo: 7). Differences between groups in both pain NRS and VMSS favored IH over placebo at all time points with medium to large effect sizes. Natrum muriaticum and Pulsatilla nigricans were the most frequently prescribed medicines. No harms, serious adverse events, or intercurrent illnesses were recorded in either group.

The authors concluded that homeopathic medicines acted significantly better than placebo in the treatment of PD. Independent replication is warranted.

A previously published RCT could not show any significant effect of homeopathy on primary dysmenorrhea in comparison with placebo. The authors of the new study claim that the discrepant findings might be due to the fact that IH requires great skill. In other words, negative studies are according to this explanation negative not because homeopathy does not work but because the prescribers are not up to it. Such notions have often been voiced on this blog and elsewhere and are used as a veritable ‘get-out clause’ for homeopathy: ONLY THE POSITIVE RESULTS ARE VALID! Consequently, systematic reviews of the evidence must only consider positive trials. And this, of course, means that the findings are invariable positive.

I find this more than a little naive and would much prefer to wait for an independent replication where ‘independent’ means that the trial is run by experts who are not advocates of homeopathy (as in the present trial).