risk/benefit

An impressive 17% of US chiropractic patients are 17 years of age or younger. This figure increases to 39% among US chiropractors who have specialized in paediatrics. Data for other countries can be assumed to be similar. But is chiropractic effective for children? All previous reviews concluded that there is a paucity of evidence for the effectiveness of manual therapy for conditions within paediatric populations.

This systematic review is an attempt to shed more light on the issue by evaluating the use of manual therapy for clinical conditions in the paediatric population, assessing the methodological quality of the studies found, and synthesizing findings based on health condition.

Of the 3563 articles identified through various literature searches, 165 full articles were screened, and 50 studies (32 RCTs and 18 observational studies) met the inclusion criteria. Only 18 studies were judged to be of high quality. Conditions evaluated were:

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

- autism,

- asthma,

- cerebral palsy,

- clubfoot,

- constipation,

- cranial asymmetry,

- cuboid syndrome,

- headache,

- infantile colic,

- low back pain,

- obstructive apnoea,

- otitis media,

- paediatric dysfunctional voiding,

- paediatric nocturnal enuresis,

- postural asymmetry,

- preterm infants,

- pulled elbow,

- suboptimal infant breastfeeding,

- scoliosis,

- suboptimal infant breastfeeding,

- temporomandibular dysfunction,

- torticollis,

- upper cervical dysfunction.

Musculoskeletal conditions, including low back pain and headache, were evaluated in seven studies. Only 20 studies reported adverse events.

The authors concluded that fifty studies investigated the clinical effects of manual therapies for a wide variety of pediatric conditions. Moderate-positive overall assessment was found for 3 conditions: low back pain, pulled elbow, and premature infants. Inconclusive unfavorable outcomes were found for 2 conditions: scoliosis (OMT) and torticollis (MT). All other condition’s overall assessments were either inconclusive favorable or unclear. Adverse events were uncommonly reported. More robust clinical trials in this area of healthcare are needed.

There are many things that I find remarkable about this review:

- The list of indications for which studies have been published confirms the notion that manual therapists – especially chiropractors – regard their approach as a panacea.

- A systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of a therapy that includes observational studies without a control group is, in my view, highly suspect.

- Many of the RCTs included in the review are meaningless; for instance, if a trial compares the effectiveness of two different manual therapies none of which has been shown to work, it cannot generate a meaningful result.

- Again, we find that the majority of trialists fail to report adverse effects. This is unethical to a degree that I lose faith in such studies altogether.

- Only three conditions are, according to the authors, based on evidence. This is hardly enough to sustain an entire speciality of paediatric chiropractors.

Allow me to have a closer look at these three conditions.

- Low back pain: the verdict ‘moderate positive’ is based on two RCTs and two observational studies. The latter are irrelevant for evaluating the effectiveness of a therapy. One of the two RCTs should have been excluded because the age of the patients exceeded the age range named by the authors as an inclusion criterion. This leaves us with one single ‘medium quality’ RCT that included a mere 35 patients. In my view, it would be foolish to base a positive verdict on such evidence.

- Pulled elbow: here the verdict is based on one RCT that compared two different approaches of unknown value. In my view, it would be foolish to base a positive verdict on such evidence.

- Preterm: Here we have 4 RCTs; one was a mere pilot study of craniosacral therapy following the infamous A+B vs B design. The other three RCTs were all from the same Italian research group; their findings have never been independently replicated. In my view, it would be foolish to base a positive verdict on such evidence.

So, what can be concluded from this?

I would say that there is no good evidence for chiropractic, osteopathic or other manual treatments for children suffering from any condition.

And why do the authors of this new review arrive at such dramatically different conclusion? I am not sure. Could it perhaps have something to do with their affiliations?

- Palmer College of Chiropractic,

- Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

- Performance Chiropractic.

What do you think?

A new update of the current Cochrane review assessed the benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for the treatment of chronic low back pain. The authors included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effect of spinal manipulation or mobilisation in adults (≥18 years) with chronic low back pain with or without referred pain. Studies that exclusively examined sciatica were excluded.

The effect of SMT was compared with recommended therapies, non-recommended therapies, sham (placebo) SMT, and SMT as an adjuvant therapy. Main outcomes were pain and back specific functional status, examined as mean differences and standardised mean differences (SMD), respectively. Outcomes were examined at 1, 6, and 12 months.

Forty-seven RCTs including a total of 9211 participants were identified. Most trials compared SMT with recommended therapies. In 16 RCTs, the therapists were chiropractors, in 14 they were physiotherapists, and in 5 they were osteopaths. They used high velocity manipulations in 18 RCTs, low velocity manipulations in 12 studies and a combination of the two in 20 trials.

Moderate quality evidence suggested that SMT has similar effects to other recommended therapies for short term pain relief and a small, clinically better improvement in function. High quality evidence suggested that, compared with non-recommended therapies, SMT results in small, not clinically better effects for short term pain relief and small to moderate clinically better improvement in function.

In general, these results were similar for the intermediate and long term outcomes as were the effects of SMT as an adjuvant therapy.

Low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months. Low quality evidence suggested that SMT results in a moderate to strong statistically significant and clinically better effect than sham SMT at one month. Additionally, very low quality evidence suggested that SMT does not result in a statistically significant better effect than sham SMT at six and 12 months.

(Mean difference in reduction of pain at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months (0-100; 0=no pain, 100 maximum pain) for spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) versus recommended therapies in review of the effects of SMT for chronic low back pain. Pooled mean differences calculated by DerSimonian-Laird random effects model.)

About half of the studies examined adverse and serious adverse events, but in most of these it was unclear how and whether these events were registered systematically. Most of the observed adverse events were musculoskeletal related, transient in nature, and of mild to moderate severity. One study with a low risk of selection bias and powered to examine risk (n=183) found no increased risk of an adverse event or duration of the event compared with sham SMT. In one study, the Data Safety Monitoring Board judged one serious adverse event to be possibly related to SMT.

The authors concluded that SMT produces similar effects to recommended therapies for chronic low back pain, whereas SMT seems to be better than non-recommended interventions for improvement in function in the short term. Clinicians should inform their patients of the potential risks of adverse events associated with SMT.

This paper is currently being celebrated (mostly) by chiropractors who think that it vindicates their treatments as being both effective and safe. However, I am not sure that this is entirely true. Here are a few reasons for my scepticism:

- SMT is as good as other recommended treatments for back problems – this may be so but, as no good treatment for back pain has yet been found, this really means is that SMT is as BAD as other recommended therapies.

- If we have a handful of equally good/bad treatments, it stand to reason that we must use other criteria to identify the one that is best suited – criteria like safety and cost. If we do that, it becomes very clear that SMT cannot be named as the treatment of choice.

- Less than half the RCTs reported adverse effects. This means that these studies were violating ethical standards of publication. I do not see how we can trust such deeply flawed trials.

- Any adverse effects of SMT were minor, restricted to the short term and mainly centred on musculoskeletal effects such as soreness and stiffness – this is how some naïve chiro-promoters already comment on the findings of this review. In view of the fact that more than half the studies ‘forgot’ to report adverse events and that two serious adverse events did occur, this is a misleading and potentially dangerous statement and a good example how, in the world of chiropractic, research is often mistaken for marketing.

- Less than half of the studies (45% (n=21/47)) used both an adequate sequence generation and an adequate allocation procedure.

- Only 5 studies (10% (n=5/47)) attempted to blind patients to the assigned intervention by providing a sham treatment, while in one study it was unclear.

- Only about half of the studies (57% (n=27/47)) provided an adequate overview of withdrawals or drop-outs and kept these to a minimum.

- Crucially, this review produced no good evidence to show that SMT has effects beyond placebo. This means the modest effects emerging from some trials can be explained by being due to placebo.

- The lead author of this review (SMR), a chiropractor, does not seem to be free of important conflicts of interest: SMR received personal grants from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), the European Centre for Chiropractic Research Excellence (ECCRE), the Belgian Chiropractic Association (BVC) and the Netherlands Chiropractic Association (NCA) for his position at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He also received funding for a research project on chiropractic care for the elderly from the European Centre for Chiropractic Research and Excellence (ECCRE).

- The second author (AdeZ) who also is a chiropractor received a grant from the European Chiropractors’ Union (ECU), for an independent study on the effects of SMT.

After carefully considering the new review, my conclusion is the same as stated often before: SMT is not supported by convincing evidence for back (or other) problems and does not qualify as the treatment of choice.

“Most of the supplement market is bogus,” Paul Clayton*, a nutritional scientist, told the Observer. “It’s not a good model when you have businesses selling products they don’t understand and cannot be proven to be effective in clinical trials. It has encouraged the development of a lot of products that have no other value than placebo – not to knock placebo, but I want more than hype and hope.” So, Dr Clayton took a job advising Lyma, a product which is currently being promoted as “the world’s first super supplement” at £199 for a one-month’s supply.

Lyma is a dietary supplement that contains a multitude of ingredients all of which are well known and available in many other supplements costing only a fraction of Lyma. The ingredients include:

- kreatinin,

- turmeric,

- Ashwagandha,

- citicoline,

- lycopene,

- vitamin D3.

Apparently, these ingredients are manufactured in special (and patented) ways to optimise their bioavailabity. According to the website, the ingredients of LYMA have all been clinically trialled with proven efficacy at levels provided within the LYMA supplement… Unless the ingredient has been clinically trialled, and peer reviewed there may be limited (if any) benefit to the body. LYMA’s revolutionary formulation is the most advanced and proven super supplement in the world, bringing together eight outstanding ingredients – seven of which are patented – to support health, wellbeing and beauty. Each ingredient has been selected for its efficacy, purity, quality, bioavailability, stability and ultimately, on the results of clinical studies.

The therapeutic claims made for the product are numerous:

- it will improve your hair, skin and nails (80% improvement in skin smoothness, 30% increase in skin moisture, 17% increase in skin elasticity, 12% reduction in wrinkle depth, 47% increase in hair strength & 35% decrease in hair loss)

- it will support energy levels in both the body and the brain (increase in brain membrane turnover by 26% and increase brain energy by 14%),

- it will improve cognitive function,

- it will enhance endurance (cardiorespiratory endurance increased by 13% compared to a placebo),

- it will improve quality of life,

- it will improve sleep (reducing insomnia by 70%),

- it will improve immunity,

- it will reduce inflammation,

- it will improve your memory,

- it will improve osteoporosis (reduce risk of osteoporosis by 37%).

These claims are backed up by 197 clinical trials, we are being told.

If true, this would be truly sensational – but is it true?

I asked the Lyma firm for the 197 original studies, and they very kindly sent me dozens papers which all referred to the single ingredients listed above. I emailed again and asked whether there are any studies of Lyma with all its ingredients in one supplement. Then I was told that they are ‘looking into a trial on the final Lyma formula‘.

I take this to mean that not a single trial of Lyma has been conducted. In this case, how do we be sure the mixture works? How can we know that the 197 studies have not been cherry-picked? How can we be sure that there are no interactions between the active constituents?

The response from Lyma quoted the above-mentioned Dr Paul Clayton stating this: “In regard to LYMA, clinical trials at this stage are not necessary. The whole point of LYMA is that each ingredient has already been extensively trialled, and validated. They have selected the best of the best ingredients, and amalgamated them; to enable consumers to take them all in a convenient format. You can quite easily go out and purchase all the ingredients separately. They aren’t easy to find, and it would mean swallowing up to 12 tablets and capsules a day; but the choice is always yours.”

It’s kind, to leave the choice to us, rather than forcing us to spend £199 each month on the world’s first super-supplement. Very kind indeed!

Having the choice, I might think again.

I might even assemble the world’s maximally evidence-based, extra super-supplement myself, one that is supported by many more than 197 peer-reviewed papers. To not directly compete with Lyma, I could use entirely different ingredients. Perhaps I should take the following five:

- Vitamin C (it has over 61 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Vitanin E (it has over 42 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Collagen (it has over 210 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Coffee (it has over 14 000 Medline listed articles to its name),

- Aloe vera (it has over 3 000 Medline listed articles to its name).

I could then claim that my extra super-supplement is supported by some 300 000 scientific articles plus 1 000 clinical studies (I am confident I could cherry-pick 1 000 positive trials from the 300 000 papers). Consequently, I would not just charge £199 but £999 for a month’s supply.

But this would be wrong, misleading, even bogus!!!, I hear you object.

On the one hand, I agree.

On the other hand, as Paul Clayton rightly pointed out: Most of the supplement market is bogus.

*If my memory serves me right, I met Paul many years ago when he was a consultant for Boots (if my memory fails me, I might need to order some Lyma).

So-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for animals is popular. A recent survey suggested that 76% of US dog and cat owners use some form of SCAM. Another survey showed that about one quarter of all US veterinary medical schools run educational programs in SCAM. Amazon currently offers more that 4000 books on the subject.

The range of SCAMs advocated for use in animals is huge and similar to that promoted for use in humans; the most commonly employed practices seem to include acupuncture, chiropractic, energy healing, homeopathy (as discussed in the previous post) and dietary supplements. In this article, I will briefly discuss the remaining 4 categories.

ACUPUNCTURE

Acupuncture is the insertion of needles at acupuncture points on the skin for therapeutic purposes. Many acupuncturists claim that, because it is over 2 000 years old, acupuncture has ‘stood the test of time’ and its long history proves acupuncture’s efficacy and safety. However, a long history of usage proves very little and might even just demonstrate that acupuncture is based on the pre-scientific myths that dominated our ancient past.

There are many different forms of acupuncture. Acupuncture points can allegedly be stimulated not just by inserting needles (the most common way) but also with heat, electrical currents, ultrasound, pressure, bee-stings, injections, light, colour, etc. Then there is body acupuncture, ear acupuncture and even tongue acupuncture. Traditional Chinese acupuncture is based on the Taoist philosophy of the balance between two life-forces, ‘yin and yang’. In contrast, medical acupuncturists tend to cite neurophysiological theories as to how acupuncture might work; even though some of these may appear plausible, they nevertheless are mere theories and constitute no proof for acupuncture’s validity.

The therapeutic claims made for acupuncture are legion. According to the traditional view, acupuncture is useful for virtually every condition. According to ‘Western’ acupuncturists, acupuncture is effective mostly for chronic pain. Acupuncture has, for instance, been used to improve mobility in dogs with musculoskeletal pain, to relieve pain associated with cervical neurological disease in dogs, for respiratory resuscitation of new-born kittens, and for treatment of certain immune-mediated disorders in small animals.

While the use of acupuncture seems to gain popularity, the evidence fails to support this. Our systematic review of acupuncture (to the best of my knowledge the only one on the subject) in animals included 14 randomized controlled trials and 17 non-randomized controlled studies. The methodologic quality of these trials was variable but, on average, it was low. For cutaneous pain and diarrhoea, encouraging evidence emerged that might warrant further investigation. Single studies reported some positive inter-group differences for spinal cord injury, Cushing’s syndrome, lung function, hepatitis, and rumen acidosis. However, these trials require independent replication. We concluded that, overall, there is no compelling evidence to recommend or reject acupuncture for any condition in domestic animals. Some encouraging data do exist that warrant further investigation in independent rigorous trials.

Serious complications of acupuncture are on record and have repeatedly been discussed on this blog: acupuncture needles can, for instance, injure vital organs like the lungs or the heart, and they can introduce infections into the body, e. g. hepatitis. About 100 human fatalities after acupuncture have been reported in the medical literature – a figure which, due to lack of a monitoring system, may disclose just the tip of an iceberg. Information on adverse effects of acupuncture in animals is currently not available.

Given that there is no good evidence that acupuncture works in animals, the risk/benefit balance of acupuncture cannot be positive.

CHIROPRACTIC

Chiropractic was created by D D Palmer (1845-1913), an American magnetic healer who, in 1895, manipulated the neck of a deaf janitor, allegedly curing his deafness. Chiropractic was initially promoted as a cure-all by Palmer who claimed that 95% of diseases were due to subluxations of spinal joints. Subluxations became the cornerstone of chiropractic ‘philosophy’, and chiropractors who adhere to Palmer’s gospel diagnose subluxation in nearly 100% of the population – even in individuals who are completely disease and symptom-free. Yet subluxations, as understood by chiropractors, do not exist.

There is no good evidence that chiropractic spinal manipulation might be effective for animals. A review of the evidence for different forms of manual therapies for managing acute or chronic pain syndromes in horses concluded that further research is needed to assess the efficacy of specific manual therapy techniques and their contribution to multimodal protocols for managing specific somatic pain conditions in horses. For other animal species or other health conditions, the evidence is even less convincing.

In humans, spinal manipulation is associated with serious complications (regularly discussed in previous posts), usually caused by neck manipulation damaging the vertebral artery resulting in a stroke and even death. Several hundred such cases have been documented in the medical literature – but, as there is no system in place to monitor such events, the true figure is almost certainly much larger. To the best of my knowledge, similar events have not been reported in animals.

Since there is no good evidence that chiropractic spinal manipulations work in animals, the risk/benefit balance of chiropractic fails to be positive.

ENERGY HEALING

Energy healing is an umbrella term for a range of paranormal healing practices, e. g. Reiki, Therapeutic Touch, Johrei healing, faith healing. Their common denominator is the belief in an ‘energy’ that can be used for therapeutic purposes. Forms of energy healing have existed in many ancient cultures. The ‘New Age’ movement has brought about a revival of these ideas, and today ‘energy’ healing systems are amongst the most popular alternative therapies in many countries.

Energy healing relies on the esoteric belief in some form of ‘energy’ which refers to some life force such as chi in Traditional Chinese Medicine, or prana in Ayurvedic medicine. Some proponents employ terminology from quantum physics and other ‘cutting-edge’ science to give their treatments a scientific flair which, upon closer scrutiny, turns out to be little more than a veneer of pseudo-science.

Considering its implausibility, energy healing has attracted a surprisingly high level of research activity in the form of clinical trials on human patients. Generally speaking, the methodologically best trials of energy healing fail to demonstrate that it generates effects beyond placebo. There are few studies of energy healing in animals, and those that are available are frequently less than rigorous (see for instance here and here). Overall, there is no good evidence to suggest that ‘energy’ healing is effective in animals.

Even though energy healing is per se harmless, it can do untold damage, not least because it can lead to neglect of effective treatments and it undermines rationality in our societies. Its risk/benefit balance therefore fails to be positive.

DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS

Dietary supplements for veterinary use form a category of remedies that, in most countries, is a regulatory grey area. Supplements can contain all sorts of ingredients, from minerals and vitamins to plants and synthetic substances. Therefore, generalisations across all types of supplements are impossible. The therapeutic claims that are being made for supplements are numerous and often unsubstantiated. Although they are usually promoted as natural and safe, dietary supplements do not have necessarily either of these qualities. For example, in the following situations, supplements can be harmful:

- Combining one supplement with another supplement or with prescribed medicines

- Substituting supplements for prescription medicines

- Overdosing some supplements, such as vitamin A, vitamin D, or iron

Examples of currently most popular supplements for use in animals include chondroitin, glucosamine, probiotics, vitamins, minerals, lutein, L-carnitine, taurine, amino acids, enzymes, St John’s wort, evening primrose oil, garlic and many other herbal remedies. For many supplements taken orally, the bioavailability might be low. There is a paucity of studies testing the efficacy of dietary supplements in animals. Three recent exceptions (all of which require independent replication) are:

- A trial showing that the dietary supplementation with Maca increased sperm production in stallions.

- A study demonstrating that curcumin supplementation appeared to reduce arthritis pain in dogs.

- An investigation suggesting that royal jelly supplementation can improve the egg quality of hens.

Dietary supplements are promoted as being free of direct risks. On closer inspection, this notion turns out to be little more than an advertising slogan. As discussed repeatedly on this blog, some supplements contain toxic materials, contaminants or adulterants and thus have the potential to do harm. A report rightly concluded that many challenges stand in the way of determining whether or not animal dietary supplements are safe and at what dosage. Supplements considered safe in humans and other cross-species are not always safe in horses, dogs, and cats. An adverse event reporting system is badly needed. And finally, regulations dealing with animal dietary supplements are in disarray. Clear and precise regulations are needed to allow only safe dietary supplements on the market.

It is impossible to generalise about the risk/benefit balance of dietary supplements; however, caution is advisable.

CONCLUSION

SCAM for animals is an important subject, not least because of the current popularity of many treatments that fall under this umbrella. For most therapies, the evidence is woefully incomplete. This means that most SCAMs are unproven. Arguably, it is unethical to use unproven medicines in routine veterinary care.

PS

I was invited several months ago to write this article for VETERINARY RECORD. It was submitted to peer review and subsequently I withdrew my submission. The above post is a slightly revised version of the original (in which I used the term ‘alternative medicine’ rather than ‘SCAM’) which also included a section on homeopathy (see my previous post). The reason for the decision to withdraw this article was the following comment by the managing editor of VETERINARY RECORD: A good number of vets use these therapies and a more balanced view that still sets out their efficacy (or otherwise) would be more useful for the readership.

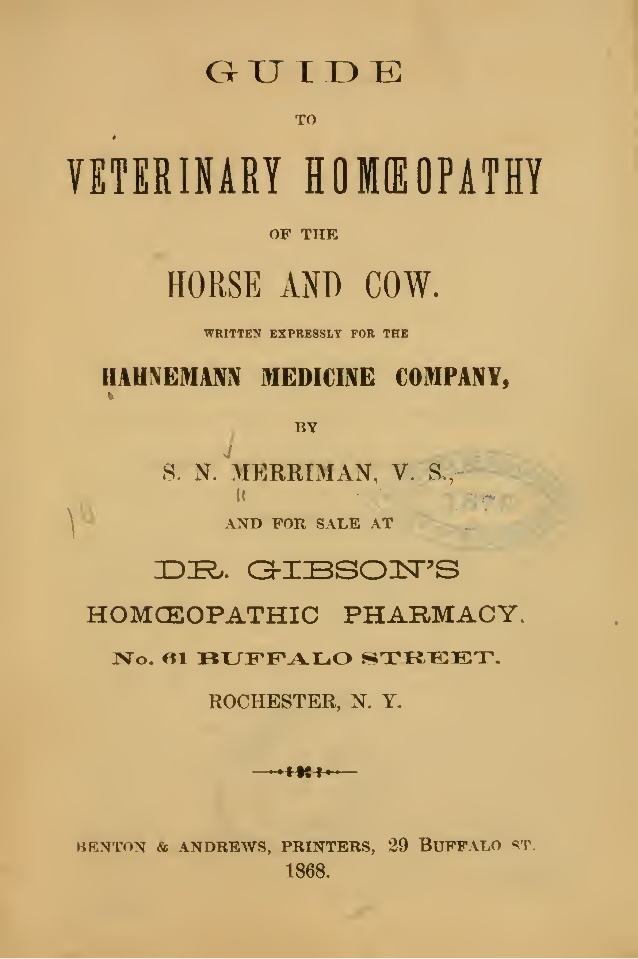

Ever since Samuel Hahnemann, the German physician who invented homeopathy, gave a lecture on the subject in the mid-1810s, homeopathy has been used for treating animals. Initially, veterinary medical schools tended to reject homoeopathy as implausible, and the number of veterinary homeopaths remained small. In the 1920ies, however, veterinary homoeopathy was revived in Germany, and in 1936, members of the “Studiengemeinschaft für tierärztliche Homöopathie” (Study Group for Veterinary Homoeopathy) started to investigate homeopathy systematically.

Today, veterinary homeopathy is popular not least because of the general boom in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Prince Charles is just one of many prominent advocates who claims to treat animals with homeopathy. In many countries, veterinary homeopaths have their own professional organisations, while elsewhere veterinarians are banned from practicing homeopathy. In the UK, only veterinarians are currently allowed to use homeopathy on animals (but ironically, anyone regardless of background can use it on human patients).

Considering the implausibility of its assumptions, it seems unlikely that homeopathic remedies can be anything other than placebos. Yet homeopaths and their followers regularly produce clinical trials that seem to suggest efficacy. Today, there are about 500 controlled clinical trials of homeopathy (mostly on humans), and it is no surprise that, purely by chance, some of them show positive results. To avoid being misled by random findings, cherry-picking, or flawed science, we ought to critically evaluate the totality of the available evidence. In other words, we should rely not on single studies but on systematic reviews of all reliable trials.

A 2015 systematic review by ardent homeopaths tested the hypothesis that the outcome of veterinary homeopathic treatments is distinguishable from placebos. A total of 15 trials could be included, but only two comprised reliable evidence without overt vested interest. The authors concluded that there is “very limited evidence that clinical intervention in animals using homeopathic medicines is distinguishable from corresponding intervention using placebos.”

A more recent systematic review compared the efficacy of homeopathy to that of antibiotics in cattle, pigs and poultry. A total number of 52 trials were included of which 28 were in favour of homeopathy and 22 showed no effect. No study had been independently replicated. The authors concluded that “the use of homeopathy cannot claim to have sufficient prognostic validity where efficacy is concerned.”

Discussing this somewhat unclear and contradictory findings of trials of homeopathy for animals, Lee et al concluded that “…it is overwhelmingly likely that small effects observed in the RCTs and systematic reviews are the result of residual bias in the trials.” To this, I might add that ‘publication bias’, i. e. the phenomenon that negative trials often remain unpublished, might be the reason why systematic reviews of homeopathy are never entirely negative.

In recent years, several scientific bodies have assessed the evidence on homeopathy and published statements about it. Here are the key passages from some of these ‘official verdicts’:

“The principles of homeopathy contradict known chemical, physical and biological laws and persuasive scientific trials proving its effectiveness are not available”

Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia

“Homeopathy should not be used to treat health conditions that are chronic, serious, or could become serious. People who choose homeopathy may put their health at risk if they reject or delay treatments for which there is good evidence for safety and effectiveness.”

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia

“These products are not supported by scientific evidence.”

Health Canada, Canada

“Homeopathic remedies don’t meet the criteria of evidence-based medicine.”

Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary

“The incorporation of anthroposophical and homeopathic products in the Swedish directive on medicinal products would run counter to several of the fundamental principles regarding medicinal products and evidence-based medicine.”

Swedish Academy of Sciences, Sweden

“There is little evidence to support homeopathy as an effective treatment for any specific condition”

National Centre for Complementary and Integrative Health, USA

“There is no good-quality evidence that homeopathy is effective as a treatment for any health condition”

“Homeopathic remedies perform no better than placebos, and the principles on which homeopathy is based are “scientifically implausible””

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, UK

“Homeopathy has not definitively proven its efficacy in any specific indication or clinical situation.”

Ministry of Health, Spain

“… homeopathy should be treated as one of the unscientific methods of the so called ‘alternative medicine’, which proposes worthless products without scientifically proven efficacy.”

National Medical Council, Poland

“… there is no valid empirical proof of the efficacy of homeopathy beyond the placebo effect.”

Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de Gezondheidszorg, Belgium

As they are usually far too dilute to contain anything, homeopathic remedies are generally harmless, provided they are produced according to good manufacturing practice (which is not always the case). Unfortunately, however, this harmlessness does not necessarily apply to homeopathy in general. When employed to replace an effective therapy, even the most innocent but ineffective treatment can become life-threatening. Since homeopaths recommend their remedies for even the most serious conditions, this is by no means a theoretical consideration. I have therefore often stated that HOMEOPATHICS MIGHT BE HARMLESS, BUT HOMEOPATHS CERTAINLY ARE NOT.

It follows that an independent risk/benefit analysis of homeopathy fails to arrive at a positive conclusion. In other words, homeopathy has not been shown to generate more good than harm. In turn, this means that homeopathy has no place in veterinary (or human) evidence-based medicine.

An article referring to comments Prof David Colquhoun and I recently made in THE TIMES about acupuncture for children caught my attention. In it, Rebecca Avern, an acupuncturist specialising in paediatrics and heading the clinical programme at the College of Integrated Chinese Medicine, makes a several statements which deserve a comment. Here is her article in full, followed by my short comments.

START OF QUOTE

However, it included some negative quotes from our old friends Ernst and Colquhoun. The first was Ernst stating that he was ‘not aware of any sound evidence showing that acupuncture is effective for any childhood conditions’. Colquhoun went further to state that there simply is not ‘the slightest bit of evidence to suggest that acupuncture helps anything in children’. Whilst they may not be aware of it, good evidence does exist, albeit for a limited number of conditions. For example, a 2016 meta-analysis and systematic review of the use of acupuncture for post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) concluded that children who received acupuncture had a significantly lower risk of PONV than those in the control group or those who received conventional drug therapy.[i]

Ernst went on to mention the hypothetical risk of puncturing a child’s internal organs but he failed to provide evidence of any actual harm. A 2011 systematic review analysing decades of acupuncture in children aged 0 to 17 years prompted investigators to conclude that acupuncture can be characterised as ‘safe’ for children.[ii]

Ernst also mentioned what he perceived is a far greater risk. He expressed concern that children would miss out on ‘effective’ treatment because they are having acupuncture. In my experience running a paediatric acupuncture clinic in Oxford, this is not the case. Children almost invariably come already having received a diagnosis from either their GP or a paediatric specialist. They are seeking treatment, such as in the case of bedwetting or chronic fatigue syndrome, because orthodox medicine is unable to effectively treat or even manage their condition. Alternatively, their condition is being managed by medication which may be causing side effects.

When it comes to their children, even those parents who may have reservations about orthodox medicine, tend to ensure their child has received all the appropriate exploratory tests. I have yet to meet a parent who will not ensure that their child, who has a serious condition, has the necessary medication, which in some cases may save their lives, such as salbutamol (usually marketed as Ventolin) for asthma or an EpiPen for anaphylactic reactions. If a child comes to the clinic where this turns out not to be the case, thankfully all BAcC members have training in a level of conventional medical sciences which enables them to spot ‘red flags’. This means that they will inform the parent that their child needs orthodox treatment either instead of or alongside acupuncture.

The article ended with a final comment from Colquhoun who believes that ‘sticking pins in babies is a rather unpleasant form of health fraud’. It is hard not to take exception to the phrase ‘sticking pins in’, whereas what we actually do is gently and precisely insert fine, sterile acupuncture needles. The needles used to treat babies and children are usually approximately 0.16mm in breadth. The average number of needles used per treatment is between two and six, and the needles are not retained. A ‘treatment’ may include not only needling, but also diet and lifestyle advice, massage, moxa, and parental education. Most babies and children find an acupuncture treatment perfectly acceptable, as the video below illustrates.

The views of Colquhoun and Ernst also beg the question of how acupuncture compares in terms of safety and proven efficacy with orthodox medical treatments given to children. Many medications given to children are so called ‘off-label’ because it is challenging to get ethical approval for randomised controlled trials in children. This means that children are prescribed medicines that are not authorised in terms of age, weight, indications, or routes of administration. A 2015 study noted that prescribers and caregivers ‘must be aware of the risk of potential serious ADRs (adverse drug reactions)’ when prescribing off-label medicines to children.[iii]

There are several reasons for the rise in paediatric acupuncture to which the article referred. Most of the time, children get better when they have acupuncture. Secondly, parents see that the treatment is gentle and well tolerated by their children. Unburdened by chronic illness, a child can enjoy a carefree childhood, and they can regain a sense of themselves as healthy. A weight is lifted off the entire family when a child returns to health. It is my belief that parents, and children, vote with their feet and that, despite people such as Ernst and Colquhoun wishing it were otherwise, more and more children will receive the benefits of acupuncture.

[i] Shin HC et al, The effect of acupuncture on post-operative nausea and vomiting after pediatric tonsillectomy: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Accessed January 2019 from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26864736

[ii] Franklin R, Few Serious Adverse Events in Pediatric Needle Acupuncture. Accessed January 2019from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/753934?src=trendmd_pilot

[iii] Aagaard L (2015) Off-Label and Unlicensed Prescribing of Medicines in Paediatric Populations: Occurrence and Safety Aspects. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. Accessed January 2019 from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/bcpt.12445

END OF QUOTE

- GOOD EVIDENCE: The systematic review cited by Mrs Avern was based mostly on poor-quality trials. It even included cohort studies without a control group. To name it as an example of good evidence, merely discloses an ignorance about what good evidence means.

- SAFETY: The article Mrs Avern referred to is a systematic review of reports on adverse events (AEs) of acupuncture in children. A total of 279 AEs were found. Of these, 25 were serious (12 cases of thumb deformity, 5 infections, and 1 case each of cardiac rupture, pneumothorax, nerve impairment, subarachnoid haemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, haemoptysis, reversible coma, and overnight hospitalization), 1 was moderate (infection), and 253 were mild. The mild AEs included pain, bruising, bleeding, and worsening of symptoms. Considering that there is no reporting system of such AEs, this list of AEs is, I think, concerning and justifies my concerns over the safety of acupuncture in children. The risks are certainly not ‘hypothetical’, as Mrs Avern claimed, and to call it thus seems to be in conflict with the highest standard of professional care (see below). Because the acupuncture community has still not established an effective AE-surveillance system, nobody can tell whether such events are frequent or rare. We all hope they are infrequent, but hope is a poor substitute for evidence.

- COMPARISON TO OTHER TREATMENTS: Mrs Avern seems to think that acupuncture has a better risk/benefit profile than conventional medicine. Having failed to show that acupuncture is effective and having demonstrated that it causes severe adverse effects, this assumption seems nothing but wishful thinking on her part.

- EXPERIENCE: Mrs Avern finishes her article by telling us that ‘children get better when they have acupuncture’. She seems to be oblivious to the fact that sick children usually get better no matter what. Perhaps the kids she treats would have improved even faster without her needles?

In conclusion, I do not doubt the good intentions of Mrs Avern for one minute; I just wished she were able to develop a minimum of critical thinking capacity. More importantly, I am concerned about the BRITISH ACUPUNCTURE COUNCIL, the organisation that published Mrs Avern’s article. On their website, they state: The British Acupuncture Council is committed to ensuring all patients receive the highest standard of professional care during their acupuncture treatment. Our Code of Professional Conduct governs ethical and professional behaviour, while the Code of Safe Practice sets benchmark standards for best practice in acupuncture. All BAcC members are bound by these codes. Who are they trying to fool?, I ask myself.

The General Chiropractic Council (GCC) is the statutory body regulating all chiropractors in the UK. Their foremost aim, they claim, is to ensure the safety of patients undergoing chiropractic treatment. They also allege to be independent and say they want to protect the health and safety of the public by ensuring high standards of practice in the chiropractic profession.

That sounds good and (almost) convincing.

But is the GCC truly fit for purpose?

In a previous post, I found good reason to doubt it.

In a recent article, the GCC claimed that they started thinking about a new five-year strategy and began to shape four key strategic aims. So, let’s have a look. Here is the crucial passage:

A clear strategy is vital but, of course, implementation and getting things changed are where the real work lie. With that in mind, we have a specific business plan for 2019 – the first year of the new strategic plan. You can read it here. This means you’ll see some really important changes and benefits including:

- Promote standards: review and improvements to CPD processes, supporting emerging new degree providers, a campaign to promote the public choosing a registered chiropractor

- Develop the profession: supporting and enabling work with the professional bodies

- Investigate and act: a full review of, and changes to, our Fitness to Practice processes to enable a more ‘right touch’ approach within our current legal framework, sharing more learning from the complaints we receive

- Deliver value: a focus on communication and engagement, further work on our culture, a new website, an upgraded registration database for an improved user experience.

The changes being introduced, backed by the GCC’s Council, will have a positive effect. I know Nick, the new Chief Executive and Registrar and the staff team will make this a success. You as chiropractors also have an important role to play – keep engaging with us and take your own action to develop the profession, share your ideas and views as we transform the organisation, and work with us to ensure we maintain public confidence in the profession of chiropractic.

END OF QUOTE

Am I the only one who finds this more than a little naïve and unprofessional? More importantly, this statement hints at a strategy mainly aimed at promoting chiropractors regardless of whether they are doing more good than harm. This, it seems, is not in line with the GCC’s stated aims.

- How can they already claim that the changes being introduced will have a positive effect?

- Where in this strategy is the GCC’s alleged foremost aim, the protection of the public?

- Where is any attempt to get chiropractic in line with the principles of EBM?

- Where is an appeal to chiropractors to adopt the standards of medical ethics?

- Where is an independent and continuous assessment of the effectiveness of chiropractic?

- Where is a critical evaluation of its safety?

- Where is an attempt to protect the public from the plethora of bogus claims made by UK chiropractors?

I feel that, given the recent history of UK chiropractic, these (and many other) points should be essential elements in any long-term strategy. I also feel that this new and potentially far-reaching statement provides little hope that the GCC is on the way towards getting fit for purpose.

Today is WORLD CANCER DAY. A good reason, I feel, to remind everyone of the existence of CAM-CANCER, an initiative that I have been involved with from its start (in fact, I was one of its initiators). Essentially, we – that is an international team of CAM-experts – conduct systematic reviews of CAMs often advertised for cancer. We then offer them as a free web resource providing the public with evidence-based information about all sorts of CAMs for cancer.

CAM-Cancer follows a strict methodology to produce CAM-summaries of high quality. Writing, review and editorial processes all follow pre-defined methods and the CAM-Cancer editorial team and Executive Committee ensure that CAM-summaries comply with the guidelines and templates. We are independent from commercial funders and strive to be as objective as possible. Most of the experts are more enthusiastic about the value of CAM than I am, but we do our very best to avoid letting sentiments get in the way of rigorous scientific assessments.

So far, we have managed to publish a respectably large and diverse array of summaries. Here is the full list:

A

- Acupuncture for breathlessness

- Acupuncture for chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting

- Acupuncture for fatigue

- Acupuncture for hot flushes

- Acupuncture for treatment-induced leukopenia

- Acupuncture in cancer pain

- Aloe vera

- Amygdalin/Laetrile

- Aromatherapy

- Artemisia absinthium

- Artemisia annua

- Autogenic therapy

B

C

D

E

F

G

- Garlic (Allium sativum)

- Gerson therapy

- Ginseng (Ginseng-Panax-ginseng-P.-quinquefolium)

- Green tea (Camellia sinensis)

H

I

L

M

- Macrobiotic diet

- Maitake (Grifola frondosa)

- Massage (Classical/Swedish)

- Melatonin

- Milk thistle (Silybum marianum)

- Milk vetch (Astragalus mongholicus)

- Mindfulness

- Mistletoe (Viscum album)

- Music therapy

N

O

P

Q

R

S

- Selenium prevention

- Selenium – during cancer treatment

- Shark cartilage

- Shiitake

- Simonton Method

- Spirulina (blue-green algae)

- St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum)

T

U

V

Y

___________________________________________________

Let me pick out just one of the summaries, Gerson therapy. This topic has led to fierce debates on my blog. The ‘key points’ of the CAM-CANCER summary are as follows:

- Gerson therapy uses a special diet, supplements and coffee enemas with the aim of detoxifying and stimulating the body’s metabolism.

- No substantial evidence exists in the scientific literature to support the claims that the Gerson therapy is an effective alternative therapy for cancer.

- Some evidence exists to suggest that elements of the therapy (coffee enemas in particular) are potentially dangerous if used excessively.

- The specific safety problems, advice to stop conventional cancer therapies and the lack of substantial evidence for efficacy outweigh any benefits associated with the Gerson therapy.

I think this is clear enough and it certainly corresponds well with what I previously wrote about Gerson on this blog. The style of presentation might be different, but the information and conclusions are almost identical.

Altogether, our CAM-CANCER summaries are well-informed, concise, and strictly evidence-based. On this WORLD CANCER DAY, I therefore warmly recommend them to everyone and sincerely hope you make good use of them, for instance, by telling other interested parties about this little-known but precious resource.

Chronic back pain is often a difficult condition to treat. Which option is best suited?

A review by the US ‘Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’ (AHRQ) focused on non-invasive nonpharmacological treatments for chronic pain. The following therapies were considered:

- exercise,

- mind-body practices,

- psychological therapies,

- multidisciplinary rehabilitation,

- mindfulness practices,

- manual therapies,

- physical modalities,

- acupuncture.

Here, I want to share with you the essence of the assessment of spinal manipulation:

- Spinal manipulation was associated with slightly greater effects than sham manipulation, usual care, an attention control, or a placebo intervention in short-term function (3 trials, pooled SMD -0.34, 95% CI -0.63 to -0.05, I2=61%) and intermediate-term function (3 trials, pooled SMD -0.40, 95% CI -0.69 to -0.11, I2=76%) (strength of evidence was low)

- There was no evidence of differences between spinal manipulation versus sham manipulation, usual care, an attention control or a placebo intervention in short-term pain (3 trials, pooled difference -0.20 on a 0 to 10 scale, 95% CI -0.66 to 0.26, I2=58%), but manipulation was associated with slightly greater effects than controls on intermediate-term pain (3 trials, pooled difference -0.64, 95% CI -0.92 to -0.36, I2=0%) (strength of evidence was low for short term, moderate for intermediate term).

This seems to confirm what I have been saying for a long time: the benefit of spinal manipulation for chronic back pain is close to zero. This means that the hallmark therapy of chiropractors for the one condition they treat more often than any other is next to useless.

But which other treatments should patients suffering from this frequent and often agonising problem employ? Perhaps the most interesting point of the AHRQ review is that none of the assessed nonpharmacological treatments are supported by much better evidence for efficacy than spinal manipulation. The only two therapies that seem to be even worse are traction and ultrasound (both are often used by chiropractors). It follows, I think, that for chronic low back pain, we simply do not have a truly effective nonpharmacological therapy and consulting a chiropractor for it does make little sense.

What else can we conclude from these depressing data? I believe, the most rational, ethical and progressive conclusion is to go for those treatments that are associated with the least risks and the lowest costs. This would make exercise the prime contender. But it would definitely exclude spinal manipulation, I am afraid.

And this beautifully concurs with the advice I recently derived from the recent Lancet papers: walk (slowly and cautiously) to the office of your preferred therapist, have a little rest there (say hello to the staff perhaps) and then walk straight back home.

In 1995, Dabbs and Lauretti reviewed the risks of cervical manipulation and compared them to those of non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They concluded that the best evidence indicates that cervical manipulation for neck pain is much safer than the use of NSAIDs, by as much as a factor of several hundred times. This article must be amongst the most-quoted paper by chiropractors, and its conclusion has become somewhat of a chiropractic mantra which is being repeated ad nauseam. For instance, the American Chiropractic Association states that the risks associated with some of the most common treatments for musculoskeletal pain—over-the-counter or prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and prescription painkillers—are significantly greater than those of chiropractic manipulation.

As far as I can see, no further comparative safety-analyses between cervical manipulation and NSAIDs have become available since this 1995 article. It would therefore be time, I think, to conduct new comparative safety and risk/benefit analyses aimed at updating our knowledge in this important area.

Meanwhile, I will attempt a quick assessment of the much-quoted paper by Dabbs and Lauretti with a view of checking how reliable its conclusions truly are.

The most obvious criticism of this article has already been mentioned: it is now 23 years old, and today we know much more about the risks and benefits of these two therapeutic approaches. This point alone should make responsible healthcare professionals think twice before promoting its conclusions.

Equally important is the fact that we still have no surveillance system to monitor the adverse events of spinal manipulation. Consequently, our data on this issue are woefully incomplete, and we have to rely mostly on case reports. Yet, most adverse events remain unpublished and under-reporting is therefore huge. We have shown that, in our UK survey, it amounted to exactly 100%.

To make matters worse, case reports were excluded from the analysis of Dabbs and Lauretti. In fact, they included only articles providing numerical estimates of risk (even reports that reported no adverse effects at all), the opinion of exerts, and a 1993 statistic from a malpractice insurer. None of these sources would lead to reliable incidence figures; they are thus no adequate basis for a comparative analysis.

In contrast, NSAIDs have long been subject to proper post-marketing surveillance systems generating realistic incidence figures of adverse effects which Dabbs and Lauretti were able to use. It is, however, important to note that the figures they did employ were not from patients using NSAIDs for neck pain. Instead they were from patients using NSAIDs for arthritis. Equally important is the fact that they refer to long-term use of NSAIDs, while cervical manipulation is rarely applied long-term. Therefore, the comparison of risks of these two approaches seems not valid.

Moreover, when comparing the risks between cervical manipulation and NSAIDs, Dabbs and Lauretti seemed to have used incidence per manipulation, while for NSAIDs the incidence figures were bases on events per patient using these drugs (the paper is not well-constructed and does not have a methods section; thus, it is often unclear what exactly the authors did investigate and how). Similarly, it remains unclear whether the NSAID-risk refers only to patients who had used the prescribed dose, or whether over-dosing (a phenomenon that surely is not uncommon with patients suffering from chronic arthritis pain) was included in the incidence figures.

It is worth mentioning that the article by Dabbs and Lauretti refers to neck pain only. Many chiropractors have in the past broadened its conclusions to mean that spinal manipulations or chiropractic care are safer than drugs. This is clearly not permissible without sound data to support such claims. As far as I can see, such data do not exist (if anyone knows of such evidence, I would be most thankful to let me see it).

To obtain a fair picture of the risks in a real life situation, one should perhaps also mention that chiropractors often fail to warn patients of the possibility of adverse effects. With NSAIDs, by contrast, patients have, at the very minimum, the drug information leaflets that do warn them of potential harm in full detail.

Finally, one could argue that the effectiveness and costs of the two therapies need careful consideration. The costs for most NSAIDs per day are certainly much lower than those for repeated sessions of manipulations. As to the effectiveness of the treatments, it is clear that NSAIDs do effectively alleviate pain, while the evidence seems far from being conclusively positive in the case of cervical manipulation.

In conclusion, the much-cited paper by Dabbs and Lauretti is out-dated, poor quality, and heavily biased. It provides no sound basis for an evidence-based judgement on the relative risks of cervical manipulation and NSAIDs. The notion that cervical manipulations are safer than NSAIDs is therefore not based on reliable data. Thus, it is misleading and irresponsible to repeat this claim.