musculoskeletal problems

A new study evaluated the effects of yoga and eurythmy therapy compared to conventional physiotherapy exercises in patients with chronic low back pain.

In this three-armed, multicentre, randomized trial, patients with chronic low back pain were treated for 8 weeks in group sessions (75 minutes once per week). They received either:

- Yoga exercises

- Eurythmy

- Physiotherapy

The primary outcome was patients’ physical disability (measured by RMDQ) from baseline to week 8. Secondary outcome variables were pain intensity and pain-related bothersomeness (VAS), health-related quality of life (SF-12), and life satisfaction (BMLSS). Outcomes were assessed at baseline, after the intervention at 8 weeks, and at a 16-week follow-up. Data of 274 participants were used for statistical analyses.

The results showed no significant differences between the three groups for the primary and secondary outcomes. In all groups, RMDQ decreased comparably at 8 weeks but did not reach clinical meaningfulness. Pain intensity and pain-related bothersomeness decreased, while the quality of life increased in all 3 groups. In explorative general linear models for the SF-12’s mental health component, participants in the eurythmy arm benefitted significantly more compared to physiotherapy and yoga. Furthermore, within-group analyses showed improvements of SF-12 mental score for yoga and eurythmy therapy only. All interventions were safe.

Everyone knows what physiotherapy or yoga is, I suppose. But what is eurythmy?

It is an exercise therapy that is part of anthroposophic medicine. It consists of a set of specific movements that were developed by Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), the inventor of anthroposophic medicine, in conjunction with Marie von Sievers (1867-1948), his second wife.

Steiner stated in 1923 that eurythmy has grown out of the soil of the Anthroposophical Movement, and the history of its origin makes it almost appear to be a gift of the forces of destiny. Steiner also wrote that it is the task of the Anthroposophical Movement to reveal to our present age that spiritual impulse that is suited to it. He claimed that, within the Anthroposophical Movement, there is a firm conviction that a spiritual impulse of this kind must enter once more into human evolution. And this spiritual impulse must perforce, among its other means of expression, embody itself in a new form of art. It will increasingly be realized that this particular form of art has been given to the world in Eurythmy.

Consumers learning eurythmy are taught exercises that allegedly integrate cognitive, emotional, and volitional elements. Eurythmy exercises are based on speech and direct the patient’s attention to their own perceived intentionality. Proponents of Eurythmy believe that, through this treatment, a connection between internal and external activity can be experienced. They also make many diffuse health claims for this therapy ranging from stress management to pain control.

There is hardly any reliable evidence for eurythmy, and therefore the present study is exceptional and noteworthy. One review concluded that “eurythmy seems to be a beneficial add-on in a therapeutic context that can improve the health conditions of affected persons. More methodologically sound studies are needed to substantiate this positive impression.” This positive conclusion is, however, of doubtful validity. The authors of the review are from an anthroposophical university in Germany. They included studies in their review that were methodologically too weak to allow any conclusions.

So, does the new study provide the reliable evidence that was so far missing? I am afraid not!

The study compared three different exercise therapies. Its results imply that all three were roughly equal. Yet, we cannot tell whether they were equally effective or equally ineffective. The trial was essentially an equivalence study, and I suspect that much larger sample sizes would have been required in order to identify any true differences if they at all exist. Lastly, the study (like the above-mentioned review) was conducted by proponents of anthroposophical medicine affiliated with institutions of anthroposophical medicine. I fear that more independent research would be needed to convince me of the value of eurythmy.

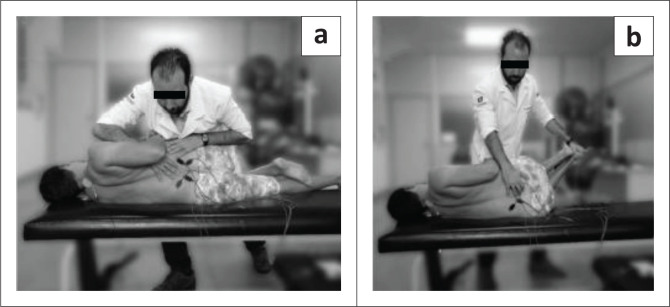

This study compared the effectiveness of two osteopathic manipulative techniques on clinical low back symptoms and trunk neuromuscular postural control in male workers with chronic low back pain (CLBP).

Ten male workers with CLBP were randomly allocated to two groups: high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) manipulation or muscle energy techniques (MET). Each group received one therapy per week for both techniques during 7 weeks of treatment.

Pain and function were measured by using the Numeric Pain-Rating Scale, the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. The lumbar flexibility was assessed by Modified Schober Test. Electromyography (EMG) and force platform measurements were used for evaluation of trunk muscular activation and postural balance, respectively at three different times: baseline, post-intervention, and 15 days later.

Both techniques were effective (p < 0.01) in reducing pain with large clinical differences (-1.8 to -2.8) across immediate and after 15 days. However, no significant effect between groups and times was found for other variables, namely neuromuscular activation, and postural balance measures.

The authors concluded that both techniques (HVLA thrust manipulation and MET) were effective in reducing back pain immediately and 15 days later. Neither technique changed the trunk neuromuscular activation patterns nor postural balance in male workers with LBP.

There is, of course, another conclusion that fits the data just as well: both techniques were equally ineffective.

Much of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) is used in the management of osteoarthritis pain. Yet few of us ever seem to ask whether SCAMs are more or less effective and safe than conventional treatments.

This review determined how many patients with chronic osteoarthritis pain respond to various non-surgical treatments. Published systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included meta-analysis of responder outcomes for at least 1 of the following interventions were included: acetaminophen, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), topical NSAIDs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, cannabinoids, counselling, exercise, platelet-rich plasma, viscosupplementation (intra-articular injections usually with hyaluronic acid ), glucosamine, chondroitin, intra-articular corticosteroids, rubefacients, or opioids.

In total, 235 systematic reviews were included. Owing to limited reporting of responder meta-analyses, a post hoc decision was made to evaluate individual RCTs with responder analysis within the included systematic reviews. New meta-analyses were performed where possible. A total of 155 RCTs were included. Interventions that led to more patients attaining meaningful pain relief compared with control included:

- exercise (risk ratio [RR] of 2.36; 95% CI 1.79 to 3.12),

- intra-articular corticosteroids (RR = 1.74; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.62),

- SNRIs (RR = 1.53; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.87),

- oral NSAIDs (RR = 1.44; 95% CI 1.36 to 1.52),

- glucosamine (RR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.74),

- topical NSAIDs (RR = 1.27; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.38),

- chondroitin (RR = 1.26; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.41),

- viscosupplementation (RR = 1.22; 95% CI 1.12 to 1.33),

- opioids (RR = 1.16; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.32).

Pre-planned subgroup analysis demonstrated no effect with glucosamine, chondroitin, or viscosupplementation in studies that were only publicly funded. When trials longer than 4 weeks were analysed, the benefits of opioids were not statistically significant.

The authors concluded that interventions that provide meaningful relief for chronic osteoarthritis pain might include exercise, intra-articular corticosteroids, SNRIs, oral and topical NSAIDs, glucosamine, chondroitin, viscosupplementation, and opioids. However, funding of studies and length of treatment are important considerations in interpreting these data.

Exercise clearly is an effective intervention for chronic osteoarthritis pain. It has consistently been recommended by international guideline groups as the first-line treatment in osteoarthritis management. The type of exercise is likely not important.

Pharmacotherapies such as NSAIDs and duloxetine demonstrate smaller but statistically significant benefit that continues beyond 12 weeks. Opioids appear to have short-term benefits that attenuate after 4 weeks, and intra-articular steroids after 12 weeks. Limited data (based on 2 RCTs) suggest that acetaminophen is not helpful. These findings are consistent with recent Osteoarthritis Research Society International guideline recommendations that no longer recommend acetaminophen for osteoarthritis pain management and strongly recommend against the use of opioids.

Limited benefit was observed with other interventions including glucosamine, chondroitin, and viscosupplementation. When only publicly funded trials were examined for these interventions, the results were no longer statistically significant.

Adverse events were inconsistently reported. However, withdrawal due to adverse events was consistently reported and found to be greater in patients using opioids, SNRIs, topical NSAIDs, and viscosupplementation.

Few of the interventions assessed fall under the umbrella of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM):

- some forms of exercise,

- cannabinoids,

- counselling,

- chondroitin,

- glucosamine.

It is unclear why the authors did not include SCAMs such as chiropractic, osteopathy, massage therapy, acupuncture, herbal medicines, neural therapy, etc. in their review. All of these SCAMs are frequently used for osteoarthritis pain. If they had included these treatments, how do you think they would have fared?

Osteopathy is a tricky subject:

- Osteopathic manipulations/mobilisations are advocated mainly for spinal complaints.

- Yet many osteopaths use them also for a myriad of non-spinal conditions.

- Osteopathy comprises two entirely different professions; in the US, osteopaths are very similar to medically trained doctors, and many hardly ever employ osteopathic manual techniques; outside the US, osteopaths are alternative practitioners who use mainly osteopathic techniques and believe in the obsolete gospel of their guru Andrew Taylor Still (this post relates to the latter type of osteopathy).

- The question whether osteopathic manual therapies are effective is still open – even for the indication that osteopaths treat most, spinal complaints.

- Like chiropractors, osteopaths now insist that osteopathy is not a treatment but a profession; the transparent reason for this argument is to gain more wriggle-room when faced with negative evidence regarding they hallmark treatment of osteopathic manipulation/mobilisation.

A new paper authored by osteopaths is an attempt to shed more light on the effectiveness of osteopathy. The aim of this systematic review evaluated the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints. Only randomized controlled trials conducted in high-income Western countries were considered. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts. Primary outcomes included ‘pain’ and ‘functional status’, while secondary outcomes included ‘medication use’ and ‘health status’.

Nineteen studies were included and qualitatively synthesized. Nine studies were from the US, followed by Germany with 7 studies. The majority of studies (n = 13) focused on low back pain.

In general, mixed findings related to the impact of osteopathic care on primary and secondary outcomes were observed. For the primary outcomes, a clear distinction between US and European studies was found, where the latter RCTs reported positive results more frequently. Studies were characterized by substantial methodological differences in sample sizes, number of treatments, control groups, and follow-up.

The authors concluded that “the findings of the current literature review suggested that osteopathic care may improve pain and functional status in patients suffering from spinal complaints. A clear distinction was observed between studies conducted in the US and those in Europe, in favor of the latter. Today, no clear conclusions of the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints can be drawn. Further studies with larger study samples also assessing the long-term impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints are required to further strengthen the body of evidence.”

Some of the most obvious weaknesses of this review include the following:

- In none of the studies employed blinding of patients, care provider or outcome assessor occurred, or it was unclear. Blinding of outcome assessors is easily implemented and should be standard in any RCT.

- In three studies, the study groups differed to some extent at baseline indicating that randomisation was not successful..

- Five studies were derived from the ‘grey literature’ and were therefore not peer-reviewed.

- One study (the UK BEAM trial) employed not just osteopaths but also chiropractors and physiotherapists for administering the spinal manipulations. It is therefore hardly an adequate test of osteopathy.

- The study was funded by an unrestricted grant from the GNRPO, the umbrella organization of the ‘Belgian Professional Associations for Osteopaths’.

Considering this last point, the authors’ honesty in admitting that no clear conclusions of the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints can be drawn is remarkable and deserves praise.

Considering that the evidence for osteopathy is even far worse for non-spinal conditions (numerous trials exist for all sorts of other conditions, but they tend to be flimsy and usually lack independent replications), it is fair to conclude that osteopathy is NOT an evidence-based therapy.

Bee venom acupuncture is a form of acupuncture in which bee venom is applied to the tips of acupuncture needles, stingers are extracted from bees, or bees are held with an instrument exposing the stinger, and applied to acupoints on the skin.

Bee venom consisting of multiple anti-inflammatory compounds such as melittin, adolapin, apamin. Other substances such as phospholipase A2 can be anti-inflammatory in low concentrations and pro-inflammatory in others. However, bee venom also contains proinflammatory substances, melittin, mast cell degranulation peptide 401, and histamine.

Bee venom acupuncture has been used to treat a number of conditions such as lumbar disc disease, osteoarthritis of the knee, rheumatoid arthritis, adhesive capsulitis, lateral epicondylitis, peripheral neuropathies, stroke and Parkinson’s Disease. The quality of these studies tends to be so poor that any verdict on the effectiveness of bee venom acupuncture would be premature.

A new clinical trial of bee-venom acupuncture for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) might change this situation. A total of 120 cases of RA patients were randomized into bee-sting acupuncture group (treatment) and western medicine group (control). The patients of the control group were treated by oral administration of Methotrexate (10 mg, once a week) and Celecoxlb (0.2 g, once a day). Those of the treatment group received 5 to 15 bee stings of Ashi-points or acupoints according to different conditions and corporeity, and with the bee-sting retained for about 5 min every time, once every other day. The treatment lasted for 8 weeks. The therapeutic effect was assessed by examining:

- symptoms and signs of the affected joints as morning stiffness duration,

- swollen/tender joint counts (indexes),

- handgrip strength,

- 15 m-walking time,

- visual analogue scale (VAS),

- Disease Activity Score including a 28-joint count (DAS 28),

- rheumatoid factor (RF),

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR),

- C-reactive protein (CRP),

- anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (ACCPA).

For assessing the safety of bee-venom acupuncture, the patients’ responses of fever, enlargement of lymph nodes, regional red and swollen, itching, blood and urine tests for routine were examined.

Findings of DAS 28 responses displayed that of the two 60 cases in the control and bee-venom acupuncture groups, 15 and 18 experienced marked improvement, 33 and 32 were effective, 12 and 10 ineffective, with the effective rates being 80% and 83. 33%, respectively. No significant difference was found between the two groups in the effective rate (P>0.05). After the treatment, both groups have witnessed a marked decrease in the levels of morning stiffness duration, arthralgia index, swollen joint count index, joint tenderness index, 15 m walking time, VAS, RF, ESR, CRP and ACCPA, and an obvious increase of handgrip strength relevant to their own levels of pre-treatment in each group (P<0.05). There were no significant differences between the two groups in the abovementioned indexes (P>0.05). The routine blood test, routine urine test, routine stool test, electrocardiogram result, the function of liver and kidney and other security index were within the normal range, without any significant adverse effects found after bee-stinging treatment.

The authors (from the Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Bao’an Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shenzhen, China) concluded that bee-venom acupuncture therapy for RA patients is safe and effective, worthy of popularization and application in clinical practice.

Where to start? There is so much – perhaps I just comment on the conclusion:

- Safety cannot be assessed on the basis of such a small sample. Bee venom can cause anaphylaxis, and several deaths have been reported in patients who successfully received the therapy prior to the adverse event. Because there is no adverse-effect monitoring system, the incidence of adverse events is unknown. Stating that it is safe, is therefore a big mistake.

- The trial was a non-superiority study. As such, it needs a much larger sample to be able to make claims about effectiveness.

- From the above two points, it follows that popularization and application in clinical practice would be a stupid exercise.

So, what is left over from this seemingly rigorous RCT?

NOTHING!

(except perhaps a re-affirmation of my often-voiced fear that we must take TCM-studies from China with more than just one pinch of salt)

Do musculoskeletal conditions contribute to chronic non-musculoskeletal conditions? The authors of a new paper – inspired by chiropractic thinking, it seems – think so. Their meta-analysis was aimed to investigate whether the most common musculoskeletal conditions, namely neck or back pain or osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, contribute to the development of chronic disease.

The authors searched several electronic databases for cohort studies reporting adjusted estimates of the association between baseline neck or back pain or osteoarthritis of the knee or hip and subsequent diagnosis of a chronic disease (cardiovascular disease , cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease or obesity).

There were 13 cohort studies following 3,086,612 people. In the primary meta-analysis of adjusted estimates, osteoarthritis (n= 8 studies) and back pain (n= 2) were the exposures and cardiovascular disease (n=8), cancer (n= 1) and diabetes (n= 1) were the outcomes. Pooled adjusted estimates from these 10 studies showed that people with a musculoskeletal condition have a 17% increase in the rate of developing a chronic disease compared to people without a musculoskeletal condition.

The authors concluded that musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease. In particular, osteoarthritis appears to increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Prevention and early

treatment of musculoskeletal conditions and targeting associated chronic disease risk factors in people with long

standing musculoskeletal conditions may play a role in preventing other chronic diseases. However, a greater

understanding about why musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease is needed.

For the most part, this paper reads as if the authors are trying to establish a causal relationship between musculoskeletal problems and systemic diseases at all costs. Even their aim (to investigate whether the most common musculoskeletal conditions, namely neck or back pain or osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, contribute to the development of chronic disease) clearly points in that direction. And certainly, their conclusion that musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease confirms this suspicion.

In their discussion, they do concede that causality is not proven: While our review question ultimately sought to assess a causal connection between common musculoskeletal conditions and chronic disease, we cannot draw strong conclusions due to poor adjustment, the analysis methods employed by the included studies, and a lack of studies investigating conditions other than OA and cardiovascular disease…We did not find studies that satisfied all of Bradford Hill’s suggested criteria for casual inference (e.g. none estimated dose–response effects) nor did we find studies that used contemporary causal inference methods for observational data (e.g. a structured identification approach for selection of confounding variables or assessment of the effects of unmeasured or residual confounders. As such, we are unable to infer a strong causal connection between musculoskeletal conditions and chronic diseases.

In all honesty, I would see this a little differently: If their review question ultimately sought to assess a causal connection between common musculoskeletal conditions and chronic disease, it was quite simply daft and unscientific. All they could ever hope is to establish associations. Whether these are causal or not is an entirely different issue which is not answerable on the basis of the data they searched for.

An example might make this clearer: people who have yellow stains on their 2nd and 3rd finger often get lung cancer. The yellow fingers are associated with cancer, yet the link is not causal. The association is due to the fact that smoking stains the fingers and causes cancer. What the authors of this new article seem to suggest is that, if we cut off the stained fingers of smokers, we might reduce the cancer risk. This is clearly silly to the extreme.

So, how might the association between musculoskeletal problems and systemic diseases come about? Of course, the authors might be correct and it might be causal. This would delight chiropractors because DD Palmer, their founding father, said that 95% of all diseases are caused by subluxation of the spine, the rest by subluxations of other joints. But there are several other and more likely explanations for this association. For instance, many people with a systemic disease might have had subclinical problems for years. These problems would prevent them from pursuing a healthy life-style which, in turn, resulted is musculoskeletal problems. If this is so, musculoskeletal conditions would not increase the risk of chronic disease, but chronic diseases would lead to musculoskeletal problems.

Don’t get me wrong, I am not claiming that this reverse causality is the truth; I am simply saying that it is one of several possibilities that need to be considered. The fact that the authors failed to do so, is remarkable and suggests that they were bent on demonstrating what they put in their conclusion. And that, to me, is an unfailing sign of poor science.

The Royal College of Chiropractors (RCC), a Company Limited by guarantee, was given a royal charter in 2013. It has following objectives:

- to promote the art, science and practice of chiropractic;

- to improve and maintain standards in the practice of chiropractic for the benefit of the public;

- to promote awareness and understanding of chiropractic amongst medical practitioners and other healthcare professionals and the public;

- to educate and train practitioners in the art, science and practice of chiropractic;

- to advance the study of and research in chiropractic.

In a previous post, I pointed out that the RCC may not currently have the expertise and know-how to meet all these aims. To support the RCC in their praiseworthy endeavours, I therefore offered to give one or more evidence-based lectures on these subjects free of charge.

And what was the reaction?

Nothing!

This might be disappointing, but it is not really surprising. Following the loss of almost all chiropractic credibility after the BCA/Simon Singh libel case, the RCC must now be busy focussing on re-inventing the chiropractic profession. A recent article published by RCC seems to confirm this suspicion. It starts by defining chiropractic:

“Chiropractic, as practised in the UK, is not a treatment but a statutorily-regulated healthcare profession.”

Obviously, this definition reflects the wish of this profession to re-invent themselves. D. D. Palmer, who invented chiropractic 120 years ago, would probably not agree with this definition. He wrote in 1897 “CHIROPRACTIC IS A SCIENCE OF HEALING WITHOUT DRUGS”. This is woolly to the extreme, but it makes one thing fairly clear: chiropractic is a therapy and not a profession.

So, why do chiropractors wish to alter this dictum by their founding father? The answer is, I think, clear from the rest of the above RCC-quote: “Chiropractors offer a wide range of interventions including, but not limited to, manual therapy (soft-tissue techniques, mobilisation and spinal manipulation), exercise rehabilitation and self-management advice, and utilise psychologically-informed programmes of care. Chiropractic, like other healthcare professions, is informed by the evidence base and develops accordingly.”

Many chiropractors have finally understood that spinal manipulation, the undisputed hallmark intervention of chiropractors, is not quite what Palmer made it out to be. Thus, they try their utmost to style themselves as back specialists who use all sorts of (mostly physiotherapeutic) therapies in addition to spinal manipulation. This strategy has obvious advantages: as soon as someone points out that spinal manipulations might not do more good than harm, they can claim that manipulations are by no means their only tool. This clever trick renders them immune to such criticism, they hope.

The RCC-document has another section that I find revealing, as it harps back to what we just discussed. It is entitled ‘The evidence base for musculoskeletal care‘. Let me quote it in its entirety:

The evidence base for the care chiropractors provide (Clar et al, 2014) is common to that for physiotherapists and osteopaths in respect of musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions. Thus, like physiotherapists and osteopaths, chiropractors provide care for a wide range of MSK problems, and may advertise that they do so [as determined by the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA)].

Chiropractors are most closely associated with management of low back pain, and the NICE Low Back Pain and Sciatica Guideline ‘NG59’ provides clear recommendations for managing low back pain with or without sciatica, which always includes exercise and may include manual therapy (spinal manipulation, mobilisation or soft tissue techniques such as massage) as part of a treatment package, with or without psychological therapy. Note that NG59 does not specify chiropractic care, physiotherapy care nor osteopathy care for the non-invasive management of low back pain, but explains that: ‘mobilisation and soft tissue techniques are performed by a wide variety of practitioners; whereas spinal manipulation is usually performed by chiropractors or osteopaths, and by doctors or physiotherapists who have undergone additional training in manipulation’ (See NICE NG59, p806).

The Manipulative Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (MACP), recently renamed the Musculoskeletal Association of Chartered Physiotherapists, is recognised as the UK’s specialist manipulative therapy group by the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists, and has approximately 1100 members. The UK statutory Osteopathic Register lists approximately 5300 osteopaths. Thus, collectively, there are approximately twice as many osteopaths and manipulating physiotherapists as there are chiropractors currently practising spinal manipulation in the UK.

END OF QUOTE

To me this sounds almost as though the RCC is saying something like this:

- We are very much like physiotherapists and therefore all the positive evidence for physiotherapy is really also our evidence. So, critics of chiropractic’s lack of sound evidence-base, get lost!

- The new NICE guidelines were a real blow to us, but we now try to spin them such that consumers don’t realise that chiropractic is no longer recommended as a first-line therapy.

- In any case, other professions also occasionally use those questionable spinal manipulations (and they are even more numerous). So, any criticism of spinal manipulation should not be directed at us but at physios and osteopaths.

- We know, of course, that chiropractors treat lots of non-spinal conditions (asthma, bed-wetting, infant colic etc.). Yet we try our very best to hide this fact and pretend that we are all focussed on back pain. This avoids admitting that, for all such conditions, the evidence suggests our manipulations to be worst than useless.

Personally, I find the RCC-strategy very understandable; after all, the RCC has to try to save the bacon for UK chiropractors. Yet, it is nevertheless an attempt at misleading the public about what is really going on. And even, if someone is sufficiently naïve to swallow this spin, one question emerges loud and clear: if chiropractic is just a limited version of physiotherapy, why don’t we simply use physiotherapists for back problems and forget about chiropractors?

(In case the RCC change their mind and want to listen to me elaborating on these themes, my offer for a free lecture still stands!)

The chiropractor Oakley Smith had graduated under D D Palmer in 1899. Smith was a former Iowa medical student who also had investigated Andrew Still’s osteopathy in Kirksville, before going to Palmer in Davenport. Eventually, Smith came to reject the Palmer concept of vertebral subluxation and developed his own concept of “the connective tissue doctrine” or naprapathy. Today, naprapathy is a popular form of manual therapy, particularly in Scandinavia and the US.

But what exactly is naprapathy? This website explains it quite well: Naprapathy is defined as a system of specific examination, diagnostics, manual treatment and rehabilitation of pain and dysfunction in the neuromusculoskeletal system. The therapy is aimed at restoring function through treatment of the connective tissue, muscle- and neural tissues within or surrounding the spine and other joints. Naprapathic treatment consists of combinations of manual techniques for instance spinal manipulation and mobilization, neural mobilization and Naprapathic soft tissue techniques, in additional to the manual techniques Naprapaths uses different types of electrotherapy, such as ultrasound, radial shockwave therapy and TENS. The manual techniques are often combined with advice regarding physical activity and ergonomics as well as medical rehabilitation training in order to decrease pain and disability and increase work ability and quality of life. A Dr. of Naprapathy is specialized in the diagnosis of structural and functional neuromusculoskeletal disorders, treatment and rehabilitation of patients with problems of such origin as well as to differentiate pain of other origin.

DOCTOR OF NAPRAPATHY? I hear you shout.

Yes, in the US, the title exists: The National College of Naprapathic Medicine is chartered by the State of Illinois and recognized by the State Board of Higher Education to grant the degree, Doctor of Naprapathy (D.N.). Graduates of the College are eligible to take the Naprapathic Medicine examination for licensure in the State of Illinois. The D.N. Degree requires:

- 66 hours – Basic Sciences

- 64 hours – Naprapathic Sciences

- 60 hours – Clinical Internship

Things become even stranger when we ask, what does the evidence show?

I found all of three clinical trials on Medline.

A 2016 clinical trial was designed to compare the treatment effect on pain intensity, pain related disability and perceived recovery from a) naprapathic manual therapy (spinal manipulation, spinal mobilization, stretching and massage) to b) naprapathic manual therapy without spinal manipulation and to c) naprapathic manual therapy without stretching for male and female patients seeking care for back and/or neck pain.

Participants were recruited among patients, ages 18-65, seeking care at the educational clinic of Naprapathögskolan – the Scandinavian College of Naprapathic Manual Medicine in Stockholm. The patients (n = 1057) were randomized to one of three treatment arms a) manual therapy (i.e. spinal manipulation, spinal mobilization, stretching and massage), b) manual therapy excluding spinal manipulation and c) manual therapy excluding stretching. The primary outcomes were minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity and pain related disability. Treatments were provided by naprapath students in the seventh semester of eight total semesters. Generalized estimating equations and logistic regression were used to examine the association between the treatments and the outcomes.

At 12 weeks follow-up, 64% had a minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity and 42% in pain related disability. The corresponding chances to be improved at the 52 weeks follow-up were 58% and 40% respectively. No systematic differences in effect when excluding spinal manipulation and stretching respectively from the treatment were found over 1 year follow-up, concerning minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity (p = 0.41) and pain related disability (p = 0.85) and perceived recovery (p = 0.98). Neither were there disparities in effect when male and female patients were analyzed separately.

The authors concluded that the effect of manual therapy for male and female patients seeking care for neck and/or back pain at an educational clinic is similar regardless if spinal manipulation or if stretching is excluded from the treatment option.

Even though this study is touted as showing that naprapathy works by advocates, in all honesty, it tells us as good as nothing about the effect of naprapathy. The data are completely consistent with the interpretation that all of the outcomes were to the natural history of the conditions, regression towards the mean, placebo, etc. and entirely unrelated to any specific effects of naprapathy.

A 2010 study by the same group was to compare the long-term effects (up to one year) of naprapathic manual therapy and evidence-based advice on staying active regarding non-specific back and/or neck pain.

Subjects with non-specific pain/disability in the back and/or neck lasting for at least two weeks (n = 409), recruited at public companies in Sweden, were included in this pragmatic randomized controlled trial. The two interventions compared were naprapathic manual therapy such as spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage and stretching, (Index Group), and advice to stay active and on how to cope with pain, provided by a physician (Control Group). Pain intensity, disability and health status were measured by questionnaires.

89% completed the 26-week follow-up and 85% the 52-week follow-up. A higher proportion in the Index Group had a clinically important decrease in pain (risk difference (RD) = 21%, 95% CI: 10-30) and disability (RD = 11%, 95% CI: 4-22) at 26-week, as well as at 52-week follow-ups (pain: RD = 17%, 95% CI: 7-27 and disability: RD = 17%, 95% CI: 5-28). The differences between the groups in pain and disability considered over one year were statistically significant favoring naprapathy (p < or = 0.005). There were also significant differences in improvement in bodily pain and social function (subscales of SF-36 health status) favoring the Index Group.

The authors concluded that combined manual therapy, like naprapathy, is effective in the short and in the long term, and might be considered for patients with non-specific back and/or neck pain.

This study is hardly impressive either. The results are consistent with the interpretation that the extra attention and care given to the index group was the cause of the observed outcomes, unrelated to ant specific effects of naprapathy.

The last study was published in 2017 again by the same group. It was designed to compare naprapathic manual therapy with evidence-based care for back or neck pain regarding pain, disability, and perceived recovery.

Four hundred and nine patients with pain and disability in the back or neck lasting for at least 2 weeks, recruited at 2 large public companies in Sweden in 2005, were included in this randomized controlled trial. The 2 interventions were naprapathy, including spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage, and stretching (Index Group) and support and advice to stay active and how to cope with pain, according to the best scientific evidence available, provided by a physician (Control Group). Pain, disability, and perceived recovery were measured by questionnaires at baseline and after 3, 7, and 12 weeks.

At 7-week and 12-week follow-ups, statistically significant differences between the groups were found in all outcomes favoring the Index Group. At 12-week follow-up, a higher proportion in the naprapathy group had improved regarding pain [risk difference (RD)=27%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 17-37], disability (RD=18%, 95% CI: 7-28), and perceived recovery (RD=44%, 95% CI: 35-53). Separate analysis of neck pain and back pain patients showed similar results.

At 7-week and 12-week follow-ups, statistically significant differences between the groups were found in all outcomes favoring the Index Group. At 12-week follow-up, a higher proportion in the naprapathy group had improved regarding pain [risk difference (RD)=27%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 17-37], disability (RD=18%, 95% CI: 7-28), and perceived recovery (RD=44%, 95% CI: 35-53). Separate analysis of neck pain and back pain patients showed similar results.

The authors thought that this trial suggests that combined manual therapy, like naprapathy, might be an alternative to consider for back and neck pain patients.

As the study suffers from the same limitations as the one above (in fact, it might be a different analysis of the same trial), they might be mistaken. I see no good reason to assume that any of the three studies provide good evidence for the effectiveness of naprapathy.

So, what should we conclude from all this?

If you ask me, naprapathy is something between chiropractic (without some of the woo) and physiotherapy (without its expertise). There is no good evidence that it works. Crucially, there is no evidence that it is superior to other therapeutic options.

I was going to finish on a positive note stating that ‘at least the ‘naprapathologists’ (I refuse to even consider the title of ‘doctor of naprapathy’) do not claim to treat conditions other than musculoskeletal problems’. But then I found this advertisement of a ‘naprapathologist’ on Twitter:

And now, I am going to finish by stating that A LOT OF NAPRAPATHY LOOKS VERY MUCH LIKE QUACKERY TO ME.

Recently, I was asked about the ‘Dorn Method’. In alternative medicine, it sometimes seems that everyone who manages to write his family name correctly has inaugurated his very own therapy. It is therefore a tall order to aim at blogging about them all. But that’s been my goal all along, and after more than 1 000 posts, I am still far from achieving it.

So, what is the Dorn Method?

A website dedicated to it provides some first-hand information. Here are a few extracts (numbers in brackets were inserted by me and refer to my comments below):

START OF QUOTE

Developed by Dieter Dorn in the 1970’s in the South of Germany, it is now fast becoming the widest used therapy for Back Pain and many Spinal Disorders in Germany (1).

The Dorn Method ist presented under different names like Dornmethod, Dorntherapy, Dorn Spinal Therapy, Dorn-Breuss Method, Dorn-XXname-method and (should) have as ‘core’ the same basic principles.

There are many supporters of the Dorn Method (2) but also Critics (see: Dorn controversy) and because it is a free (3) Method and therefore not bound to clear defined rules and regulations, this issue will not change so quickly.

The Method is featured in numerous books and medical expositions (4), taught to medical students in some universities (5), covered by most private medical insurances (6) and more and more recognized in general (7).

However because it is fairly new and not developed by a Medical Professional it is often still considered an alternative Healing Method and it is meant to stay FREE of becoming a registered trademark, following the wish of the Founder Dieter Dorn (†2011) who did NOT execute his sole right to register this Method as the founder, this Method must become socalled Folk Medicine.

As of now only licensed Therapists, Non Medical Practitioners (in Germany called Heilpraktiker (Healing Practitioners with Government recognition) (8), Physical Therapists or Medical Doctors are authorized to practice with government license, but luckily the Dorn Method is mainly a True Self Help Method therefore all other Dorn Method Practitioners can legally help others by sharing it in this way (9).

What conditions can be treated with the Dorn Method? Every disease, even up to the psychological domain can be treated (positively influenced) unless an illness had already led to irreversible damages at organs (10). The main areas of application are: Muscle-Skeletal Disorders (incl. Back Pain, Sciatica, Scoliosis, Joint-Pain, Muscular Tensions, Migraines etc.)

END OF QUOTE

My brief comments:

- This is a gross exaggeration.

- Clearly another exaggeration.

- Not ‘free’ in the sense of costing nothing, surely!

- Yet another exaggeration.

- I very much doubt that.

- I also have difficulties believing this statement.

- I see no evidence for this.

- We have repeatedly discussed the Heilpraktiker on this blog, see for instance here, here and here.

- Sorry, but I fail to understand the meaning of this statement.

- I am always sceptical of claims of this nature.

By now, we all are keen to know what evidence there might be to suggest that the Dorn Method works. The website of the Dorn Method claims that there are 4 different strands of evidence:

START OF QUOTE

1. A new form of manual therapy and self help method which is basically unknown in conventional medicine until now, with absolutely revolutionary new knowledge. It concerns for example the manual adjustment of a difference in length of legs as a consequence of a combination of subluxation of the hip-joint (subluxation=partly luxated=misaligned) and a subluxation of the joints of sacrum (Ilio-sacral joint) and possible knee and ankle joints. The longer leg is considered the ‘problem’-leg and Not the shorter leg as believed in classical medicine and chiropractic.

2. The osteopathic knowledge that there is a connection of each vertebra and its appropriate spinal segment to certain inner organs. That means that when there are damages at these structures, disturbances of organic functions are the consequence, which again are the base for the arising of diseases.

3. The knowledge of the Chinese medicine, especially of acupuncture and meridian science that the organic functions are stirred and leveled, also among each other, via the vegetative nervous system

4. The natural-scientific knowledge of anatomy, physiology, physics, chemistry and other domains.

END OF QUOTE

One does not need to be a master in critical thinking to realise that these 4 strands amount to precisely NOTHING in terms of evidence for the Dorn Method. I therefore conducted several searches and have to report that, to the best of my knowledge, there is not a jot of evidence to suggest that the Dorm Method is more than hocus-pocus.

In case you wonder what actually happens when a patient – unaware of this lack of evidence – consults a clinician using the Dorn Method, the above website provides us with some interesting details:

START OF QUOTE

First the patients leg length is controlled and if necessary corrected in a laying position. The hip joint is brought to a (more or less) 90 degree position and the leg is then brought back to its straight position while guiding the bones back into its original place with gentle pressure.

This can be done by the patient and it is absolutely safe, easy and painless!

The treatment of Knees and Ankles should then follow with the same principals: Gentle pressure towards the Joint while moving it from a bended to a more straight position.

After the legs the pelvis is checked for misalignment and also corrected if necessary in standing position.

Followed by the lumbar vertebrae and lower thoracic columns, also while standing upright.

Then the upper thoracic vertebrae are checked, corrected if necessary, and finally the cervical vertebrae, usually in a sitting position.

The treatment often is continued by the controlling and correction of other joints like the shoulders, elbow, hands and others like the jaw or collarbone.

END OF QUOTE

Even if we disregard the poor English used throughout the text, we cannot possibly escape the conclusion that the Dorn Method is pure nonsense. So, why do some practitioners practice it?

The answer to this question is, of course, simple: There is money in it!

“Average fees for Dorn Therapy sessions range from about 40€ to 100€ or more… Average fees for Dorn Method Seminars range from about 180€ to 400€ in most developed countries for a two day basic or review or advanced training.”

SAY NO MORE!

Chiropractic is hugely popular, we are often told. The fallacious implication is, of course, that popularity can serve as a surrogate measure for effectiveness. In the United States, chiropractors provided 18.6 million clinical services under Medicare in 2015, and overall spending for chiropractic services was estimated at USD $12.5 billion. Elsewhere, chiropractic seems to be less commonly used, and the global situation has not recently been outlined. The authors of this ‘global overview‘ might fill this gap by summarizing the current literature on the utilization of chiropractic services, reasons for seeking care, patient profiles, and assessment and treatment provided.

Systematic searches were conducted in MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Index to Chiropractic Literature from database inception to January 2016. Eligible articles

1) were published in English or French (not all that global then!);

2) were case series, descriptive, cross-sectional, or cohort studies;

3) described patients receiving chiropractic services;

4) reported on the following theme(s): utilization rates of chiropractic services; reasons for attending chiropractic care; profiles of chiropractic patients; or, types of chiropractic services provided.

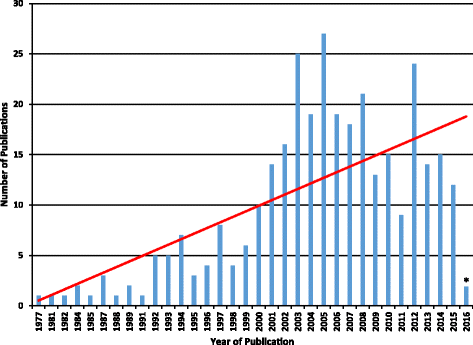

The literature searches retrieved 328 studies (reported in 337 articles) that reported on chiropractic utilization (245 studies), reason for attending chiropractic care (85 studies), patient demographics (130 studies), and assessment and treatment provided (34 studies).

Globally, the median 12-month utilization of chiropractic services was 9.1% (interquartile range (IQR): 6.7%-13.1%) and remained stable between 1980 and 2015. Most patients consulting chiropractors were female (57.0%, IQR: 53.2%-60.0%) with a median age of 43.4 years (IQR: 39.6-48.0), and were employed.

The most common reported reasons for people attending chiropractic care were (median) low back pain (49.7%, IQR: 43.0%-60.2%), neck pain (22.5%, IQR: 16.3%-24.5%), and extremity problems (10.0%, IQR: 4.3%-22.0%). The most common treatment provided by chiropractors included (median) spinal manipulation (79.3%, IQR: 55.4%-91.3%), soft-tissue therapy (35.1%, IQR: 16.5%-52.0%), and formal patient education (31.3%, IQR: 22.6%-65.0%).

The authors concluded that this comprehensive overview on the world-wide state of the chiropractic profession documented trends in the literature over the last four decades. The findings support the diverse nature of chiropractic practice, although common trends emerged.

My interpretation of the data presented is somewhat different from that of the authors. For instance, I fail to share the notion that utilization remained stable over time.

The figure might not be totally conclusive, but I seem to detect a peak in 2005, followed by a decline. Also, as the vast majority of studies originate from the US, I find it difficult to conclude anything about global trends in utilization.

Some of the more remarkable findings of this paper include the fact that 3.1% (IQR: 1.6%-6.1%) of the general population sought chiropractic care for visceral/non-musculoskeletal conditions. Some of the reasons for attending chiropractic care reported by the paediatric population are equally noteworthy: 7% for infections, 5% for asthma, and 5% for stomach problems. Globally, 5% of all consultations were for wellness/maintenance. None of these indications is even remotely evidence-based, of course.

Remarkably, 35% of chiropractors used X-ray diagnostics, and only 31% did a full history of their patients. Spinal manipulation was used by 79%, 31% sold nutritional supplements to their patients, and 10% used applied kinesiology.

In general, this is an informative paper. However, it suffers from a distinct lack of critical input. It seems to skip over almost all areas that might be less than favourable for chiropractors. The reason for this becomes clear, I think, when we read the source of funding for the research: PJHB, AEB, SAM and SDF have received research funding from the Canadian national and provincial chiropractic organizations, either as salary support or for research project funding. JJW received research project funding from the Ontario Chiropractic Association, outside the submitted work. SDF is Deputy Editor-in-Chief for Chiropractic and Manual Therapies; however, he did not have any involvement in the editorial process for this manuscript and was blinded from the editorial system for this paper from submission to decision.