migraine

This update of a systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of spinal manipulations as a treatment for migraine headaches.

Amed, Embase, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Mantis, Index to Chiropractic Literature, and Cochrane Central were searched from inception to September 2023. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) investigating spinal manipulations (performed by various healthcare professionals including physiotherapists, osteopaths, and chiropractors) for treating migraine headaches in human subjects were considered. Other types of manipulative therapy, i.e., cranial, visceral, and soft tissue were excluded. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to evaluate the certainty of evidence.

Three more RCTs were published since our first review; amounting to a total of 6 studies with 645 migraineurs meeting the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis of six trials showed that, compared with various controls (placebo, drug therapy, usual care), SMT (with or without usual care) has no superior effect on migraine intensity/severity measured with a range of instruments (standardized mean difference [SMD] − 0.22, 95% confidence intervals [CI] − 0.65 to 0.21, very low certainty evidence), migraine duration (SMD − 0.10; 95% CI − 0.33 to 0.12, 4 trials, low certainty evidence), or emotional quality of life (SMD − 14.47; 95% CI − 31.59 to 2.66, 2 trials, low certainty evidence) at post-intervention. A meta-analysis of two trials showed that compared with various controls, SMT (with or without usual care) increased the risk of adverse effects (risk ratio [RR] 2.06; 95% CI 1.24 to 3.41, numbers needed to harm = 6; very low certainty evidence). The main reasons for downgrading the evidence were study limitations (studies judged to be at an unclear or high risk of bias), inconsistency (for pain intensity/severity), imprecision (small sizes and wide confidence intervals around effect estimates) and indirectness (methodological and clinical heterogeneity of populations, interventions, and comparators).

We cocluded that the effectiveness of SMT for the treatment of migraines remains unproven. Future, larger, more rigorous, and independently conducted studies might reduce the existing uncertainties.

The only people who might be surprised by these conclusions are chiropractors who continue to advertise and use SMT to treat migraines. Here are a few texts by chiropractors (many including impressive imagery) that I copied from ‘X’ just now (within less that 5 minutes) to back up this last statement:

- So many people are suffering with Dizziness and migraines and do not know what to do. Upper Cervical Care is excellent at realigning the upper neck to restore proper blood flow and nerve function to get you feeling better!

- Headache & Migraine Relief! Occipital Lift Chiropractic Adjustment

- Are migraines affecting your quality of life? Discover effective chiropractic migraine relief at…

- Neck Pain, Migraine & Headache Relief Chiropractic Cracks

- Migraine Miracle: Watch How Chiropractic Magic Erases Shoulder Pain! Y-Strap Adjustments Unveiled

- Tired of letting migraines control your life? By addressing underlying issues and promoting spinal health, chiropractors can help reduce the frequency and severity of migraines. Ready to experience the benefits of chiropractic for migraine relief?

- Did you know these conditions can be treated by a chiropractor? Subluxation, Back Pain, Chronic Pain, Herniated Disc, Migraine Headaches, Neck Pain, Sciatica, and Sports Injuries.

- When a migraine comes on, there is not much you can do to stop it except wait it out. However, here are some holistic and non-invasive tips and tricks to prevent onset. Check out that last one! In addition to the other tips, chiropractic care may prevent migraines in your future!

Evidence-based chiropractic?

MY FOOT!

To date, two open-label clinical trials have indicated that acupuncture may be more effective than standard medication for chronic migraine. However, drawing definitive conclusions from these trials is challenging. Studies employing a double-dummy design can eliminate the placebo effect and offer more unbiased estimates of efficacy.

This double-dummy, single-blind, randomized controlled trial compared the efficacy and safety of acupuncture and topiramate for chronic migraine. Participants, aged 18–65 years and diagnosed with chronic migraine, were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive:

- acupuncture (three sessions/week) plus topiramate placebo (acupuncture group),

- or topiramate (50–100 mg/day) plus sham acupuncture (topiramate group) over 12 weeks.

The primary outcome was the mean change in monthly migraine days during weeks 1–12.

Of 123 screened patients, 60 (mean age 45.8, 81.7% female) were randomly assigned to the acupuncture or topiramate groups. Acupuncture demonstrated significantly greater reductions in monthly migraine days than topiramate. No severe adverse events were reported.

The authors concluded that acupuncture may be safe and effective for treating chronic migraine. The efficacy of 12 weeks of acupuncture was sustained for 24 weeks and superior to that of topiramate. Acupuncture can be used as an optional preventive therapy for chronic migraine.

I beg to differ!

The authors claim that the participants, outcome assessors, and statistical analysts were blinded (masked) to the group allocations. However, the success of patient blinding was not tested. Why?

The authors state that, in the acupuncture group, “twirling, lifting, and thrusting were performed to produce deqi (a sensation of soreness, numbness, distention, or heaviness that indicates effective needling)… In the topiramate group, sham acupuncture was administered on non-effective acupoints, without manual deqi manipulations.” In other words, patients could very easily tell to which group they had been randomised.

This, in turn, means that a placebo effect – possibly enhanced by verbal or non-verbal communication from the (non-blinded) actupuncturists – has most likely caused the observed outcomes. I therefore feel the need to re-phrase the authors’ conclusions:

This study confirms that acupuncture produces a large placebo effect. Whether it has any effects beyond placebo cannot be determined by this study. Until this point has been clarified, acupuncture should not be used as a preventive therapy for chronic migraine.

NICE helps practitioners and commissioners get the best care to patients, fast, while ensuring value for the taxpayer. Internationally, NICE has a reputation for being reliable and trustworthy. But is that also true for its recommendations regarding the use of acupuncture? NICE currently recommends that patients consider acupuncture as a treatment option for the following conditions:

- chronic (long-term) pain

- chronic tension-type headaches

- migraines

- prostatitis symptoms

- hiccups

Confusingly, on a different site, NICE also recommends acupuncture for retinal migraine, a very specific type of migraine that affect normally just one eye with symptoms such as vision loss lasting up to one hour, a blind spot in the vision, headache, blurred vision and seeing flashing lights, zigzag patterns or coloured spots or lines, as well as feeling nauseous or being sick.

I think this perplexing situation merits a look at the evidence. Here I quote the conclusions of recent, good quality, and (where possible) independent reviews:

- Chronic pain: Acupuncture is efficacious for reducing pain in patients with LBP… Further research needs to be done to evaluate acupuncture’s efficacy in these conditions, especially for abdominal pain, as many of the current studies have a risk of bias due to lack of blinding and small sample size.

- Chronic tension-type headaches (TTH): Acupuncture may be an effective and safe treatment for TTH patients. Due to low or very low certainty of evidence and high heterogeneity, more rigorous RCTs are needed to verify the effect and safety of acupuncture in the management of TTH.

- Migraines: Many studies suggest that acupuncture is a safe, helpful and available alternative therapy that may be beneficial to certain migraine patients. Nevertheless, further large-scale RCTs are warranted to further consolidate these findings and provide further support for the clinical value of acupuncture. Despite previous studies that have analyzed the effects of acupuncture on migraine, there is still a need for further investigation to ensure that the incorporation of acupuncture into migraine treatment management will have a positive outcome on patients.

- Prostatitis: This meta-analysis indicated that acupuncture has measurable benefits on CP/CPPS, and security has also been ensured. However, this meta-analysis only included 10 RCTs; thus, RCTs with a larger sample size and longer-term observation are required to verify the effectiveness of acupuncture further in the future.

- Hiccups: All of these studies sought to determine the effectiveness of different acupuncture techniques in the treatment of persistent and intractable hiccups. All four studies had a high risk of bias, did not compare the intervention with placebo, and failed to report side effects or adverse events for either the treatment or control groups.

- Retinal migraine: no evidence

So, what do we make of this? I think that, on the basis of the evidence:

- a positive recommendation for all types of chromic pain is not warranted;

- a positive recommendation for the treatment of TTH is questionable;

- a positive recommendation for migraine is questionable;

- a positive recommendation for prostatitis is questionable;

- a positive recommendation for hiccups is not warranted;

- a positive recommendation for retinal migraine is not warranted.

But why did NICE issue positive recommendations despite weak or even non-existent evidence?

SEARCH ME!

.

The ‘American Heart Association News’ recently reported the case of a 33-year-old woman who suffered a stroke after consulting a chiropractor. I take the liberty of reproducing sections of this article:

Kate Adamson liked exercising so much, her goal was to become a fitness trainer. She grew up in New Zealand playing golf and later, living in California, she worked out often while raising her two young daughters. Although she was healthy and ate well, she had occasional migraines. At age 33, they were getting worse and more frequent. One week, she had the worst headache of her life. It went on for days. She wasn’t sleeping well and got up early to take a shower. She felt a wave of dizziness. Her left side seemed to collapse. Adamson made her way down to the edge of the tub to rest. She was able to return to bed, where she woke up her husband, Steven Klugman. “I need help now,” she said.

Her next memory was seeing paramedics rushing into the house while her 3-year-old daughter, Stephanie, was in the arms of a neighbor. Rachel, her other daughter, then 18 months old, was still asleep. When she woke up in the hospital, Adamson found herself surrounded by doctors. Klugman was by her side. She could see them, hear them and understand them. But she could not move or react.

Doctors told Klugman that his wife had experienced a massive brain stem stroke. It was later thought to be related to neck manipulations she had received from a chiropractor for the migraines. The stroke resulted in what’s known as locked-in syndrome, a disorder of the nervous system. She was paralyzed except for the muscles that control eye movement. Adamson realized she could answer yes-or-no questions by blinking her eyes.

Klugman was told that Adamson had a very minimal chance of recovery. She was put on a ventilator to breathe, given nutrition through a feeding tube, and had to use a catheter. She learned to coordinate eye movements to an alphabet chart. This enabled her to make short sentences. “Am I going to die?” she asked one of her doctors. “No, we’re going to get you into rehab,” he said.

Adamson stayed in the ICU on life support for 70 days before being transferred to an acute rehabilitation facility. She could barely move a finger, but that small bit of progress gave her hope. In rehab, she slowly started to regain use of her right side; her left side remained paralyzed. Therapists taught her to swallow and to speak. She had to relearn to blow her nose, use the toilet and tie her shoes.

She was particularly fond of a social worker named Amy who would incorporate therapy exercises into visits with her children, such as bubble blowing to help her breathing. Amy, who Adamson became friends with, also helped the children adjust to seeing their mother in a wheelchair.

Adamson changed her dream job from fitness trainer to hospital social worker. She left rehab three and a half months later, still in a wheelchair but able to breathe, eat and use the toilet on her own. She continued outpatient rehab for another year. She assumed her left side would improve as her right side did. But it remained paralyzed. She would need to use a brace on her left leg to walk and couldn’t use her left arm and hand. Still, two years after the stroke, which happened in 1995, Adamson was able to drive with a few equipment modifications…

In 2018, Adamson reached another milestone. She graduated with a master’s degree in social work; she’d started college in 2011 at age 49. “It wasn’t easy going to school. I just had to take it a day at a time, a semester at a time,” she said. “The stroke has taught me I can walk through anything.” …

Now 60, she works with renal transplant and pulmonary patients, helping coordinate their services and care with the rest of the medical team at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “Knowing that you’re making a difference in somebody’s life is very satisfying. It takes me back to when I was a patient – I’m always looking at how I would want to be treated,” she said. “I’ve really come full circle.”

Adamson has adapted to doing things one-handed in a two-handed world, such as cooking and tying her shoes. She also walks with a cane. To stay in shape, she works with a trainer doing functional exercises and strength training. She has a special glove that pulls her left hand into a fist, allowing her to use a rowing machine and stationary bike….

Adamson is especially determined when it comes to helping her patients. “I work really hard to be an example to them, to show that we are all capable of going through difficult life challenges while still maintaining a positive attitude and making a difference in the world.”

________________________

What can we learn from this story?

Mainly two things, in my view:

- We probably should avoid chiropractors and certainly not allow them to manipulate our necks. I know, chiros will say that the case proves nothing. I agree, it does not prove anything, but the mere suspicion that the lock-in syndrome was caused by a stroke that, in turn, was due to upper spinal manipulation plus the plethora of cases where causality is much clearer are, I think, enough to issue that caution.

- Having been in rehab medicine for much of my early career, I feel it is good to occasionally point out how important this sector often neglected part of healthcare can be. Rehab medicine has been a sensible form of multidisciplinary, integrative healthcare long before the enthusiasts of so-called alternative medicine jumped on the integrative bandwagon.

Migraines are common headache disorders and risk factors for subsequent strokes. Acupuncture has been widely used in the treatment of migraines; however, few studies have examined whether its use reduces the risk of strokes in migraineurs. This study explored the long-term effects of acupuncture treatment on stroke risk in migraineurs using national real-world data.

A team of Taiwanese researchers collected new migraine patients from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2017. Using 1:1 propensity-score matching, they assigned patients to either an acupuncture or non-acupuncture cohort and followed up until the end of 2018. The incidence of stroke in the two cohorts was compared using the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Each cohort was composed of 1354 newly diagnosed migraineurs with similar baseline characteristics. Compared with the non-acupuncture cohort, the acupuncture cohort had a significantly reduced risk of stroke (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.35–0.46). The Kaplan–Meier model showed a significantly lower cumulative incidence of stroke in migraine patients who received acupuncture during the 19-year follow-up (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

The authors concluded that acupuncture confers protective benefits on migraineurs by reducing the risk of stroke. Our results provide new insights for clinicians and public health experts.

After merely 10 minutes of critical analysis, ‘real-world data’ turn out to be real-bias data, I am afraid.

The first question to ask is, were the groups at all comparable? The answer is, NO; the acupuncture group had

- more young individuals;

- fewer laborers;

- fewer wealthy people;

- fewer people with coronary heart disease;

- fewer individuals with chronic kidney disease;

- fewer people with mental disorders;

- more individuals taking multiple medications.

And that are just the variables that were known to the researcher! There will be dozens that are unknown but might nevertheless impact on a stroke prognosis.

But let’s not be petty and let’s forget (for a minute) about all these inequalities that render the two groups difficult to compare. The potentially more important flaw in this study lies elsewhere.

Imagine a group of people who receive some extra medical attention – such as acupuncture – over a long period of time, administered by a kind and caring therapist; imagine you were one of them. Don’t you think that it is likely that, compared to other people who do not receive this attention, you might feel encouraged to look better after your health? Consequently, you might do more exercise, eat more healthily, smoke less, etc., etc. As a result of such behavioral changes, you would be less likely to suffer a stroke, never mind the acupuncture.

SIMPLE!

I am not saying that such studies are totally useless. What often renders them worthless or even dangerous is the fact that the authors are not more self-critical and don’t draw more cautious conclusions. In the present case, already the title of the article says it all:

Acupuncture Is Effective at Reducing the Risk of Stroke in Patients with Migraines: A Real-World, Large-Scale Cohort Study with 19-Years of Follow-Up

My advice to researchers of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and journal editors publishing their papers is this: get your act together, learn about the pitfalls of flawed science (most of my books might assist you in this process), and stop misleading the public. Do it sooner rather than later!

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of craniosacral therapy on different features in migraine patients.

Fifty individuals with migraine were randomly divided into two groups (n = 25 per group):

- craniosacral therapy group (CTG),

- sham control group (SCG).

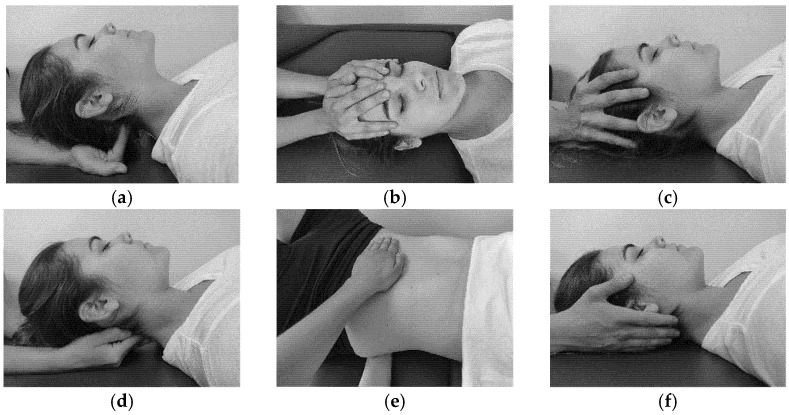

The interventions were carried out with the patient in the supine position. The CTG received a manual therapy treatment focused on the craniosacral region including five techniques, and the SCG received a hands-on placebo intervention. After the intervention, individuals remained supine with a neutral neck and head position for 10 min, to relax and diminish tension after treatment. The techniques were executed by the same experienced physiotherapist in both groups.

The analyzed variables were pain, migraine severity, and frequency of episodes, functional, emotional, and overall disability, medication intake, and self-reported perceived changes, at baseline, after a 4-week intervention, and at an 8-week follow-up.

After the intervention, the CTG significantly reduced pain (p = 0.01), frequency of episodes (p = 0.001), functional (p = 0.001) and overall disability (p = 0.02), and medication intake (p = 0.01), as well as led to a significantly higher self-reported perception of change (p = 0.01), when compared to SCG. The results were maintained at follow-up evaluation in all variables.

The authors concluded that a protocol based on craniosacral therapy is effective in improving pain, frequency of episodes, functional and overall disability, and medication intake in migraineurs. This protocol may be considered as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients.

Sorry, but I disagree!

And I have several reasons for it:

- The study was far too small for such strong conclusions.

- For considering any treatment as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients, we would need at least one independent replication.

- There is no plausible rationale for craniosacral therapy to work for migraine.

- The blinding of patients was not checked, and it is likely that some patients knew what group they belonged to.

- There could have been a considerable influence of the non-blinded therapists on the outcomes.

- There was a near-total absence of a placebo response in the control group.

Altogether, the findings seem far too good to be true.

Two recent reviews have evaluated the evidence for acupuncture as a means of preventing migraine attacks.

The first review assessed the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of episodic or chronic migraine in adult patients compared to pharmacological treatment.

The authors included randomized controlled trials published in western languages that compared any treatment involving needle insertion (with or without manual or electrical stimulation) at acupuncture points, pain points or trigger points, with any pharmacological prophylaxis in adult (≥18 years) with chronic or episodic migraine with or without aura according to the criteria of the International Headache Society.

Nine randomized trials were included encompassing 1,484 patients. At the end of the intervention, a small reduction was found in favor of acupuncture for the number of days with migraine per month: (SMD: -0.37; 95% CI -1.64 to -0.11), and for response rate (RR: 1.46; 95% CI 1.16-1.84). A moderate effect emerged in the reduction of pain intensity in favor of acupuncture (SMD: -0.36; 95% CI -0.60 to -0.13), and a large reduction in favor of acupuncture in both the dropout rate due to any reason (RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.84) and the dropout rate due to adverse event (RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.74). The quality of the evidence was moderate for all these primary outcomes. Results at longest follow-up confirmed these effects.

The authors concluded that, based on moderate certainty of evidence, we conclude that acupuncture is mildly more effective and much safer than medication for the prophylaxis of migraine.

The second review aimed to perform a network meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness and acceptability between topiramate, acupuncture, and Botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT-A).

The authors searched OVID Medline, Embase, the Cochrane register of controlled trials (CENTRAL), the Chinese Clinical Trial Register, and clinicaltrials.gov for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared topiramate, acupuncture, and BoNT-A with any of them or placebo in the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. A network meta-analysis was performed by using a frequentist approach and a random-effects model. The primary outcomes were the reduction in monthly headache days and monthly migraine days at week 12. Acceptability was defined as the number of dropouts owing to adverse events.

A total of 15 RCTs (n = 2545) could be included. Eleven RCTs were at low risk of bias. The network meta-analyses (n = 2061) showed that acupuncture (2061 participants; standardized mean difference [SMD] -1.61, 95% CI: -2.35 to -0.87) and topiramate (582 participants; SMD -0.4, 95% CI: -0.75 to -0.04) ranked the most effective in the reduction of monthly headache days and migraine days, respectively; but they were not significantly superior over BoNT-A. Topiramate caused the most treatment-related adverse events and the highest rate of dropouts owing to adverse events.

The authors concluded that Topiramate and acupuncture were not superior over BoNT-A; BoNT-A was still the primary preventive treatment of chronic migraine. Large-scale RCTs with direct comparison of these three treatments are warranted to verify the findings.

Unquestionably, these are interesting findings. How reliable are they? Acupuncture trials are in several ways notoriously tricky, and many of the primary studies were of poor quality. This means the results are not as reliable as one would hope. Yet, it seems to me that migraine prevention is one of the indications where the evidence for acupuncture is strongest.

A second question might be practicability. How realistic is it for a patient to receive regular acupuncture sessions for migraine prevention? And finally, we might ask how cost-effective acupuncture is for that purpose and how its cost-effectiveness compares to other options.

The objective of this trial, just published in the BMJ, was to assess the efficacy of manual acupuncture as prophylactic treatment for acupuncture naive patients with episodic migraine without aura. The study was designed as a multi-centre, randomised, controlled clinical trial with blinded participants, outcome assessment, and statistician. It was conducted in 7 hospitals in China with 150 acupuncture naive patients with episodic migraine without aura.

They were given the following treatments:

- 20 sessions of manual acupuncture at true acupuncture points plus usual care,

- 20 sessions of non-penetrating sham acupuncture at heterosegmental non-acupuncture points plus usual care,

- usual care alone over 8 weeks.

The main outcome measures were change in migraine days and migraine attacks per 4 weeks during weeks 1-20 after randomisation compared with baseline (4 weeks before randomisation).

A total of 147 were included in the final analyses. Compared with sham acupuncture, manual acupuncture resulted in a significantly greater reduction in migraine days at weeks 13 to 20 and a significantly greater reduction in migraine attacks at weeks 17 to 20. The reduction in mean number of migraine days was 3.5 (SD 2.5) for manual versus 2.4 (3.4) for sham at weeks 13 to 16 and 3.9 (3.0) for manual versus 2.2 (3.2) for sham at weeks 17 to 20. At weeks 17 to 20, the reduction in mean number of attacks was 2.3 (1.7) for manual versus 1.6 (2.5) for sham. No severe adverse events were reported. No significant difference was seen in the proportion of patients perceiving needle penetration between manual acupuncture and sham acupuncture (79% v 75%).

The authors concluded that twenty sessions of manual acupuncture was superior to sham acupuncture and usual care for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine without aura. These results support the use of manual acupuncture in patients who are reluctant to use prophylactic drugs or when prophylactic drugs are ineffective, and it should be considered in future guidelines.

Considering the many flaws in most acupuncture studies discussed ad nauseam on this blog, this is a relatively rigorous trial. Yet, before we accept the conclusions, we ought to evaluate it critically.

The first thing that struck me was the very last sentence of its abstract. I do not think that a single trial can ever be a sufficient reason for changing existing guidelines. The current Cochrance review concludes that the available evidence suggests that adding acupuncture to symptomatic treatment of attacks reduces the frequency of headaches. Thus, one could perhaps argue that, together with the existing data, this new study might strengthen its conclusion.

In the methods section, the authors state that at the end of the study, we determined the maintenance of blinding of patients by asking them whether they thought the needles had penetrated the skin. And in the results section, they report that they found no significant difference between the manual acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups for patients’ ability to correctly guess their allocation status.

I find this puzzling, since the authors also state that they tried to elicit acupuncture de-qi sensation by the manual manipulation of needles. They fail to report data on this but this attempt is usually successful in the majority of patients. In the control group, where non-penetrating needles were used, no de-qi could be generated. This means that the two groups must have been at least partly de-blinded. Yet, we learn from the paper that patients were not able to guess to which group they were randomised. Which statement is correct?

This may sound like a trivial matter, but I fear it is not.

Like this new study, acupuncture trials frequently originate from China. We and others have shown that Chinese trials of acupuncture hardly ever produce a negative finding. If that is so, one does not need to read the paper, one already knows that it is positive before one has even seen it. Neither do the researchers need to conduct the study, one already knows the result before the trial has started.

You don’t believe the findings of my research nor those of others?

Excellent! It’s always good to be sceptical!

But in this case, do you believe Chinese researchers?

In this systematic review, all RCTs of acupuncture published in Chinese journals were identified by a team of Chinese scientists. An impressive total of 840 trials were found. Among them, 838 studies (99.8%) reported positive results from primary outcomes and two trials (0.2%) reported negative results. The authors concluded that publication bias might be major issue in RCTs on acupuncture published in Chinese journals reported, which is related to high risk of bias. We suggest that all trials should be prospectively registered in international trial registry in future.

So, at least three independent reviews have found that Chinese acupuncture trials report virtually nothing but positive findings. Is that enough evidence to distrust Chinese TCM studies?

Perhaps not!

But there are even more compelling reasons for taking evidence from China with a pinch of salt:

A survey of clinical trials in China has revealed fraudulent practice on a massive scale. China’s food and drug regulator carried out a one-year review of clinical trials. They concluded that more than 80 percent of clinical data is “fabricated“. The review evaluated data from 1,622 clinical trial programs of new pharmaceutical drugs awaiting regulator approval for mass production. According to the report, much of the data gathered in clinical trials are incomplete, failed to meet analysis requirements or were untraceable. Some companies were suspected of deliberately hiding or deleting records of adverse effects, and tampering with data that did not meet expectations. “Clinical data fabrication was an open secret even before the inspection,” the paper quoted an unnamed hospital chief as saying. Chinese research organisations seem have become “accomplices in data fabrication due to cutthroat competition and economic motivation.”

So, am I claiming the new acupuncture study just published in the BMJ is a fake?

No!

Am I saying that it would be wise to be sceptical?

Yes.

Sadly, my scepticism is not shared by the BMJ’s editorial writer who concludes that the new study helps to move acupuncture from having an unproven status in complementary medicine to an acceptable evidence based treatment.

Call me a sceptic, but that statement is, in my view, hard to justify!

Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (CSMT) for migraine?

Why?

There is no good evidence that it works!

On the contrary, there is good evidence that it does NOT work!

A recent and rigorous study (conducted by chiropractors!) tested the efficacy of chiropractic CSMT for migraine. It was designed as a three-armed, single-blinded, placebo -controlled RCT of 17 months duration including 104 migraineurs with at least one migraine attack per month. Active treatment consisted of CSMT (group 1) and the placebo was a sham push manoeuvre of the lateral edge of the scapula and/or the gluteal region (group 2). The control group continued their usual pharmacological management (group 3). The results show that migraine days were significantly reduced within all three groups from baseline to post-treatment. The effect continued in the CSMT and placebo groups at all follow-up time points (groups 1 and 2), whereas the control group (group 3) returned to baseline. The reduction in migraine days was not significantly different between the groups. Migraine duration and headache index were reduced significantly more in the CSMT than in group 3 towards the end of follow-up. Adverse events were few, mild and transient. Blinding was sustained throughout the RCT. The authors concluded that the effect of CSMT observed in our study is probably due to a placebo response.

One can understand that, for chiropractors, this finding is upsetting. After all, they earn a good part of their living by treating migraineurs. They don’t want to lose patients and, at the same time, they need to claim to practise evidence-based medicine.

What is the way out of this dilemma?

Simple!

They only need to publish a review in which they dilute the irritatingly negative result of the above trial by including all previous low-quality trials with false-positive results and thus generate a new overall finding that alleges CSMT to be evidence-based.

This new systematic review of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) evaluated the evidence regarding spinal manipulation as an alternative or integrative therapy in reducing migraine pain and disability.

The searches identified 6 RCTs eligible for meta-analysis. Intervention duration ranged from 2 to 6 months; outcomes included measures of migraine days (primary outcome), migraine pain/intensity, and migraine disability. Methodological quality varied across the studies. The results showed that spinal manipulation reduced migraine days with an overall small effect size as well as migraine pain/intensity.

The authors concluded that spinal manipulation may be an effective therapeutic technique to reduce migraine days and pain/intensity. However, given the limitations to studies included in this meta-analysis, we consider these results to be preliminary. Methodologically rigorous, large-scale RCTs are warranted to better inform the evidence base for spinal manipulation as a treatment for migraine.

Bob’s your uncle!

Perhaps not perfect, but at least the chiropractic profession can now continue to claim they practice something akin to evidence-based medicine, while happily cashing in on selling their unproven treatments to migraineurs!

But that’s not very fair; research is not for promotion, research is for finding the truth; this white-wash is not in the best interest of patients! I hear you say.

Who cares about fairness, truth or conflicts of interest?

Christine Goertz, one of the review-authors, has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the Director of the Inter‐Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR). Peter M. Wayne, another author, has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the co‐Director of the Inter‐Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR)

And who the Dickens are the NCMIC and the IINCR?

At NCMIC, they believe that supporting the chiropractic profession, including chiropractic research programs and projects, is an important part of our heritage. They also offer business training and malpractice risk management seminars and resources to D.C.s as a complement to the education provided by the chiropractic colleges.

The IINCR is a collaborative effort between PCCR, Yale Center for Medical Informatics and the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. They aim at creating a chiropractic research portfolio that’s truly translational. Vice Chancellor for Research and Health Policy at Palmer College of Chiropractic Christine Goertz, DC, PhD (PCCR) is the network director. Peter Wayne, PhD (Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School) will join Anthony J. Lisi, DC (Yale Center for Medical Informatics and VA Connecticut Healthcare System) as a co-director. These investigators will form a robust foundation to advance chiropractic science, practice and policy. “Our collective efforts provide an unprecedented opportunity to conduct clinical and basic research that advances chiropractic research and evidence-based clinical practice, ultimately benefiting the patients we serve,” said Christine Goertz.

Really: benefiting the patients?

You could have fooled me!

This systematic review was aimed at evaluating the effects of acupuncture on the quality of life of migraineurs. Only randomized controlled trials that were published in Chinese and English were included. In total, 62 trials were included for the final analysis; 50 trials were from China, 3 from Brazil, 3 from Germany, 2 from Italy and the rest came from Iran, Israel, Australia and Sweden.

Acupuncture resulted in lower Visual Analog Scale scores than medication at 1 month after treatment and 1-3 months after treatment. Compared with sham acupuncture, acupuncture resulted in lower Visual Analog Scale scores at 1 month after treatment.

The authors concluded that acupuncture exhibits certain efficacy both in the treatment and prevention of migraines, which is superior to no treatment, sham acupuncture and medication. Further, acupuncture enhanced the quality of life more than did medication.

The authors comment in the discussion section that the overall quality of the evidence for most outcomes was of low to moderate quality. Reasons for diminished quality consist of the following: no mentioned or inadequate allocation concealment, great probability of reporting bias, study heterogeneity, sub-standard sample size, and dropout without analysis.

Further worrisome deficits are that only 14 of the 62 studies reported adverse effects (this means that 48 RCTs violated research ethics!) and that there was a high level of publication bias indicating that negative studies had remained unpublished. However, the most serious concern is the fact that 50 of the 62 trials originated from China, in my view. As I have often pointed out, such studies have to be categorised as highly unreliable.

In view of this multitude of serious problems, I feel that the conclusions of this review must be re-formulated:

Despite the fact that many RCTs have been published, the effect of acupuncture on the quality of life of migraineurs remains unproven.