insomnia

A ‘pragmatic, superiority, open-label, randomised controlled trial’ of sleep restriction therapy versus sleep hygiene has just been published in THE LANCET. Adults with insomnia disorder were recruited from 35 general practices across England and randomly assigned (1:1) using a web-based randomisation programme to either four sessions of nurse-delivered sleep restriction therapy plus a sleep hygiene booklet or a sleep hygiene booklet only. There was no restriction on usual care for either group. Outcomes were assessed at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. The primary endpoint was self-reported insomnia severity at 6 months measured with the insomnia severity index (ISI). The primary analysis included participants according to their allocated group and who contributed at least one outcome measurement. Cost-effectiveness was evaluated from the UK National Health Service and personal social services perspective and expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. The trial was prospectively registered (ISRCTN42499563).

Between Aug 29, 2018, and March 23, 2020 the researchers randomly assigned 642 participants to sleep restriction therapy (n=321) or sleep hygiene (n=321). Mean age was 55·4 years (range 19–88), with 489 (76·2%) participants being female and 153 (23·8%) being male. 580 (90·3%) participants provided data for at least one outcome measurement. At 6 months, mean ISI score was 10·9 (SD 5·5) for sleep restriction therapy and 13·9 (5·2) for sleep hygiene (adjusted mean difference –3·05, 95% CI –3·83 to –2·28; p<0·0001; Cohen’s d –0·74), indicating that participants in the sleep restriction therapy group reported lower insomnia severity than the sleep hygiene group. The incremental cost per QALY gained was £2076, giving a 95·3% probability that treatment was cost-effective at a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000. Eight participants in each group had serious adverse events, none of which were judged to be related to intervention.

The authors concluded that brief nurse-delivered sleep restriction therapy in primary care reduces insomnia symptoms, is likely to be cost-effective, and has the potential to be widely implemented as a first-line treatment for insomnia disorder.

I am frankly amazed that this paper was published in a top journal, like THE LANCET. Let me explain why:

The verum treatment was delivered over four consecutive weeks, involving one brief session per week (two in-person sessions and two sessions over the phone). Session 1 introduced the rationale for sleep restriction therapy alongside a review of sleep diaries, helped participants to select bed and rise times, advised on management of daytime sleepiness (including implications for driving), and discussed barriers to and facilitators of implementation. Session 2, session 3, and session 4 involved reviewing progress, discussion of difficulties with implementation, and titration of the sleep schedule according to a sleep efficiency algorithm.

This means that the verum group received fairly extensive attention, while the control group did not. In other words, a host of non-specific effects are likely to have significantly influenced or even entirely determined the outcome. Despite this rather obvious limitation, the authors fail to discuss any of it. On the contrary, that claim that “we did a definitive test of whether brief sleep restriction therapy delivered in primary care is clinically effective and cost-effective.” This is, in my view, highly misleading and unworthy of THE LANCET. I suggest the conclusions of this trial should be re-formulated as follows:

The brief nurse-delivered sleep restriction, or the additional attention provided exclusively to the patients in the verum group, or a placebo-effect or some other non-specific effect reduced insomnia symptoms.

Alternatively, one could just conclude from this study that poor science can make it even into the best medical journals – a problem only too well known in the realm of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

Electroacupuncture (EA) is often advocated for depression and sleep disorders but its efficacy remains uncertain. The aim of this study was, therefore, to “assess the efficacy and safety of EA as an alternative therapy in improving sleep quality and mental state for patients with insomnia and depression.”

A 32-week patient- and assessor-blinded, randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial (8-week intervention plus 24-week follow-up) was conducted from September 1, 2016, to July 30, 2019, at 3 tertiary hospitals in Shanghai, China. Patients were randomized to receive

- EA treatment and standard care,

- sham acupuncture (SA) treatment and standard care,

- standard care only as control.

Patients in the EA or SA groups received a 30-minute treatment 3 times per week (usually every other day except Sunday) for 8 consecutive weeks. All treatments were performed by licensed acupuncturists with at least 5 years of clinical experience. A total of 6 acupuncturists (2 at each center; including X.Y. and S.Z.) performed EA and SA, and they received standardized training on the intervention method before the trial. The regular acupuncture method was applied at the Baihui (GV20), Shenting (GV24), Yintang (GV29), Anmian (EX-HN22), Shenmen (HT7), Neiguan (PC6), and SanYinjiao (SP6) acupuncture points, with 0.25 × 25-mm and 0.30 × 40-mm real needles (Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd), or 0.30 × 30-mm sham needles (Streitberger sham device [Asia-med GmbH]).

For patients in the EA group, rotating or lifting-thrusting manipulation was applied for deqi sensation after needle insertion. The 2 electrodes of the electrostimulator (CMNS6-1 [Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd]) were connected to the needles at GV20 and GV29, delivering a continuous wave based on the patient’s tolerance. Patients in the SA group felt a pricking sensation when the blunt needle tip touched the skin, but without needle insertion. All indicators of the nearby electrostimulator were set to 0, with the light switched on. Standard care (also known as treatment as usual or routine care) was used in the control group. Patients receiving standard care were recommended by the researchers to get regular exercise, eat a healthy diet, and manage their stress level during the trial. They were asked to keep the regular administration of antidepressants, sedatives, or hypnotics as well. Psychiatrists in the Shanghai Mental Health Center (including X.L.) guided all patients’ standard care treatment and provided professional advice when a patient’s condition changed.

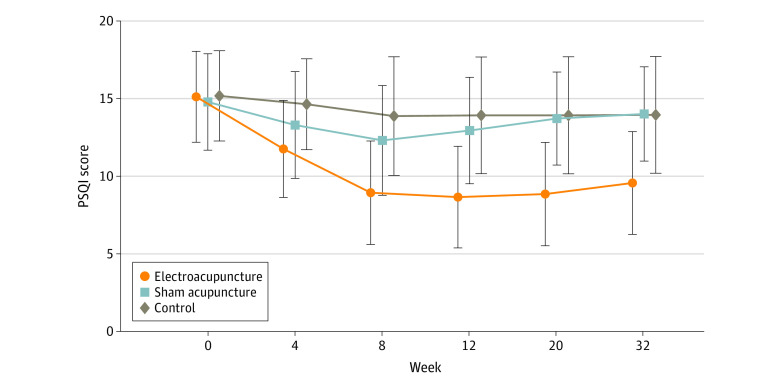

The primary outcome was change in Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) from baseline to week 8. Secondary outcomes included PSQI at 12, 20, and 32 weeks of follow-up; sleep parameters recorded in actigraphy; Insomnia Severity Index; 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score; and Self-rating Anxiety Scale score.

Among the 270 patients (194 women [71.9%] and 76 men [28.1%]; mean [SD] age, 50.3 [14.2] years) included in the intention-to-treat analysis, 247 (91.5%) completed all outcome measurements at week 32, and 23 (8.5%) dropped out of the trial. The mean difference in PSQI from baseline to week 8 within the EA group was -6.2 (95% CI, -6.9 to -5.6). At week 8, the difference in PSQI score was -3.6 (95% CI, -4.4 to -2.8; P < .001) between the EA and SA groups and -5.1 (95% CI, -6.0 to -4.2; P < .001) between the EA and control groups. The efficacy of EA in treating insomnia was sustained during the 24-week postintervention follow-up. Significant improvement in the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (-10.7 [95% CI, -11.8 to -9.7]), Insomnia Severity Index (-7.6 [95% CI, -8.5 to -6.7]), and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (-2.9 [95% CI, -4.1 to -1.7]) scores and the total sleep time recorded in the actigraphy (29.1 [95% CI, 21.5-36.7] minutes) was observed in the EA group during the 8-week intervention period (P < .001 for all). No between-group differences were found in the frequency of sleep awakenings. No serious adverse events were reported.

The result of the blinding assessment showed that 56 patients (62.2%) in the SA group guessed wrongly about their group assignment (Bang blinding index, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.6 to −0.3]), whereas 15 (16.7%) in the EA group also guessed wrongly (Bang blinding index, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.4-0.7]). This indicated a relatively higher degree of blinding in the SA group.

The authors concluded that, in this randomized clinical trial of EA treatment for insomnia in patients with depression, quality of sleep improved significantly in the EA group compared with the SA or control group at week 8 and was sustained at week 32.

This trial seems rigorous, it has a sizable sample size, uses a credible placebo procedure, and is reported in sufficient detail. Why then am I skeptical?

- Perhaps because we have often discussed how untrustworthy acupuncture studies from China are?

- Perhaps because I fail to see a plausible mechanism of action?

- Perhaps because the acupuncturists could not be blinded and thus might have influenced the outcome?

- Perhaps because the effects of sham acupuncture seem unreasonably small?

- Perhaps because I cannot be sure whether the acupuncture or the electrical current is supposed to have caused the effects?

- Perhaps because the authors of the study are from institutions such as the Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Huadong Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai,

- Perhaps because the results seem too good to be true?

If you have other and better reasons, I’d be most interested to hear them.

Yes, Today is ‘WORLD SLEEP DAY‘ and you are probably in bed hoping this post will put you back to sleep.

This study aimed to synthesise the best available evidence on the safety and efficacy of using moxibustion and/or acupuncture to manage cancer-related insomnia (CRI).

The PRISMA framework guided the review. Nine databases were searched from its inception to July 2020, published in English or Chinese. Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) of moxibustion and or acupuncture for the treatment of CRI were selected for inclusion. The methodological quality was assessed using the method suggested by the Cochrane collaboration. The Cochrane Review Manager was used to conduct a meta-analysis.

Fourteen RCTs met the eligibility criteria; 7 came from China. Twelve RCTs used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score as continuous data and a meta-analysis showed positive effects of moxibustion and or acupuncture (n = 997, mean difference (MD) = -1.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) = -2.75 to -0.94, p < 0.01). Five RCTs using continuous data and a meta-analysis in these studies also showed significant difference between two groups (n = 358, risk ratio (RR) = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.26-0.80, I 2 = 39%).

The authors concluded that the meta-analyses demonstrated that moxibustion and or acupuncture showed a positive effect in managing CRI. Such modalities could be considered an add-on option in the current CRI management regimen.

Even at the risk of endangering your sleep, I disagree with this conclusion. Here are some of my reasons:

- Chinese acupuncture trials invariably are positive which means they are as reliable as a 4£ note.

- Most trials were of poor methodological quality.

- Only one made an attempt to control for placebo effects.

- Many followed the A+B versus B design which invariably produces (false-) positive results.

- Only 4 out of 14 studies mentioned adverse events which means that 10 violated research ethics.

Sorry to have disturbed your sleep!

Acupuncture is a veritable panacea; it cures everything! At least this is what many of its advocates want us to believe. Does it also have a role in supportive cancer care?

Let’s find out.

This systematic review evaluated the effects of acupuncture in women with breast cancer (BC), focusing on patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

A comprehensive literature search was carried out for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting PROs in BC patients with treatment-related symptoms after undergoing acupuncture for at least four weeks. Literature screening, data extraction, and risk bias assessment were independently carried out by two researchers. The authors stated that they followed the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) guidelines.

Out of the 2, 524 identified studies, 29 studies representing 33 articles were included in this meta-analysis. The RCTs employed various acupuncture techniques with a needle, such as hand-acupuncture and electroacupuncture. Sham/placebo acupuncture, pharmacotherapy, no intervention, or usual care were the control interventions. About half of the studies lacked adequate blinding.

At the end of treatment (EOT), the acupuncture patients’ quality of life (QoL) was measured by the QLQ-C30 QoL subscale, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endocrine Symptoms (FACT-ES), the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General/Breast (FACT-G/B), and the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MENQOL), which depicted a significant improvement. The use of acupuncture in BC patients lead to a considerable reduction in the scores of all subscales of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) measuring pain. Moreover, patients treated with acupuncture were more likely to experience improvements in hot flashes scores, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and anxiety compared to those in the control group, while the improvements in depression were comparable across both groups. Long-term follow-up results were similar to the EOT results. Eleven RCTs did not report any information on adverse effects.

The authors concluded that current evidence suggests that acupuncture might improve BC treatment-related symptoms measured with PROs including QoL, pain, fatigue, hot flashes, sleep disturbance and anxiety. However, a number of included studies report limited amounts of certain subgroup settings, thus more rigorous, well-designed and larger RCTs are needed to confirm our results.

This review looks rigorous on the surface but has many weaknesses if one digs only a little deeper. To start with, it has no precise research question: is any type of acupuncture better than any type of control? This is not a research question that anyone can answer with just a few studies of mostly poor quality. The authors claim to follow the PRISMA guidelines, yet (as a co-author of these guidelines) I can assure you that this is not true. Many of the included studies are small and lacked blinding. The results are confusing, contradictory and not clearly reported. Many trials fail to mention adverse effects and thus violate research ethics, etc., etc.

The conclusion that acupuncture might improve BC treatment-related symptoms could be true. But does this paper convince me that acupuncture DOES improve these symptoms?

No!

Bach flower remedies were invented in the 1920s by Dr. Edward Bach (1886-1936), a doctor homeopath who had previously worked in the London Homeopathic Hospital. They have since become very popular in Europe and beyond. Bach flower remedies are clearly inspired by homeopathy; however, they are not the same because they do not follow the ‘like cures like’ principle and are they potentized. They are manufactured by placing freshly picked specific flowers or parts of plants in water which is subsequently mixed with alcohol, bottled, and sold. Like most homeopathic remedies, they are highly dilute and thus do not contain therapeutic amounts of the plant printed on the bottle.

The aim of this new randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was to compare the efficacy of flower therapy for the treatment of anxiety in overweight or obese adults with that of a placebo. The authors examined improvement in sleep patterns, reduction in binge eating, and change in resting heart rate (RHR).

The study included 40 participants in the placebo group and 41 in the intervention group. Participants were of both genders, from 20 to 59 years of age, overweight or obese, with moderate to high anxiety. They were randomized into two groups:

- one group was treated with Bach flower remedies (BFR) (bottles containing 30 mL of 30% hydro-brandy solution with two drops each of Impatiens, White Chestnut, Cherry Plum, Chicory, Crab Apple, and Pine), purchased from Healing® Flower Essences (São Paulo, Brazil)

- the other group was given a placebo (same solution without BFR).

All patients were instructed to orally ingest the solutions by placing four drops directly in the mouth four times a day for 4 weeks.

The primary outcome was anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI]). Secondary outcomes were sleep (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]), binge eating (Binge Eating Scale [BES]), and RHR (electrocardiogram).

Multivariate analysis showed significant reductions in scores for the following variables in the intervention group when compared with the placebo group: STAI (β = −0.190; p < 0.001), PSQI (β = −0.160; p = 0.027), BES (β = −0.226; p = 0.001), and RHR (β = −0.07; p = 0.003).

The authors concluded that anxiety symptoms, binge eating, and RHRs of the individuals treated with flower therapy decreased, and their sleep patterns improved when compared with those treated with the placebo.

Did the alcohol in the verum preparation had a relaxing effect? No, I was teasing. The amount would have been too small and the effect would have been the same in both groups. But what could have caused the observed outcome? I have to admit that I have no idea.

I read the study several times and could not find a major flaw. Hence it must have been the flower remedy that caused the positive outcome? No, I am teasing again. I find this impossible to imagine. These remedies contain nothing that might explain the results and all previous systematic reviews of all the available trials have all reached a negative conclusion. Before I seriously consider the option that flower remedies are more than placebos, I would like to see an independent replication.

Reflexology (originally called ‘zone therapy’ by its inventor) is a manual technique where pressure is applied to the sole of the patient’s foot. Reflexology is said to have its roots in ancient cultures. Its current popularity goes back to the US doctor William Fitzgerald (1872-1942) who did some research in the early 1900s and thought to have discovered that the human body is divided into 10 zones each of which is represented on the sole of the foot. Reflexologists thus drew maps of the sole of the foot where all the body’s organs are depicted. Numerous such maps have been published and, embarrassingly, they do not all agree with each other as to the location of our organs on the sole of our feet. By massaging specific zones which are assumed to be connected to specific organs, reflexologists believe to positively influence the function of these organs.

So, does reflexology do more good than harm?

The aim of this review was to conduct a systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression to determine the current best available evidence of the efficacy and safety of foot reflexology for adult depression, anxiety, and sleep quality.

Twenty-six studies could be included. The meta-analyses showed that foot reflexology intervention significantly improved adult depression, anxiety, and sleep quality. Metaregression revealed that an increase in total foot reflexology time and duration can significantly improve sleep quality.

The authors concluded that foot reflexology may provide additional nonpharmacotherapy intervention for adults suffering from depression, anxiety, or sleep disturbance. However, high quality and rigorous design RCTs in specific population, along with an increase in participants, and a long-term follow-up are recommended in the future.

Sounds good!

Finally a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that is backed by soild evidence!

Or perhaps not?

Here are a few concerns that lead me to doubt these conclusions:

- Most of the primary studies were of poor methodological quality.

- Most studies failed to mention adverse effects.

- Very few studies controlled for placebo effects.

- There was evidence of publication bias (negative studies tended to remain unpublished).

- Studies published in languages other than English were not considered.

- The authors fail to point out that a foot massage is, of course, agreeable (and thus may relieve a range of symptoms), but reflexology with all its weird assumptions is less than plausible.

- Many of the studies located by the authors were excluded for reasons that are less than clear.

The last point seems particularly puzzling. Our own trial, for instance, was excluded because, according to the review authors, it did not include relevant outcomes. However, our method secion makes it clear that the primary focus for this study was the subscores for anxiety and depression, which comprise four and seven items, respectively. As it happens, our study was negative.

Also cuirous is the fact that the authors did not mention our own 2011 systematic review of reflexology:

Reflexology is a popular form of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The aim of this update is to critically evaluate the evidence for or against the effectiveness of reflexology in patients with any type of medical condition. Six electronic databases were searched to identify all relevant randomised clinical trials (RCTs). Their methodological quality was assessed independently by the two reviewers using the Jadad score. Overall, 23 studies met all inclusion criteria. They related to a wide range of medical conditions. The methodological quality of the RCTs was often poor. Nine high quality RCTs generated negative findings; and five generated positive findings. Eight RCTs suggested that reflexology is effective for the following conditions: diabetes, premenstrual syndrome, cancer patients, multiple sclerosis, symptomatic idiopathic detrusor over-activity and dementia yet important caveats remain. It is concluded that the best clinical evidence does not demonstrate convincingly reflexology to be an effective treatment for any medical condition.

I wonder why!

Highly diluted homeopathic remedies are pure placebos! This is what the best evidence clearly shows. Ergo they cannot be shown in a rigorous study to have effects that differ from placebo. But now there is a study that seems to contradict this widely accepted conclusion.

Can someone please help me to understand what is going on?

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT, 60 patients suffering from insomnia were treated either individualised homeopathy (IH) or placebo for 3 months. Patient-administered sleep diary and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) were used the primary and secondary outcomes respectively, measured at baseline, and after 3 months.

Five patients dropped out (verum:2,control:3).Intention to treat sample (n=60) was analysed. Trial arms were comparable at baseline. In the verum group, except sleep diary item 3 (P= 0.371), rest of the outcomes improved significantly (all P < 0.01). In the control group, there were significant improvements in diary item 6 and ISI score (P < 0.01) and just significant improvement in item 5 (P= 0.018). Group differences were significant for items 4, 5 and 6(P < 0.01) and just significant (P= 0.014) for ISI score with moderate to large effect sizes; but non-significant (P > 0.01) for rest of the outcomes.

The authors concluded that in this double-blind, randomized, prospective, placebo-controlled, two parallel arms clinical trial conducted on 60 patients suffering from insomnia, there was statistically significant difference measured in sleep efficiency, total sleep time, time in bed, and ISI score in favour of homeopathy over placebo with moderate to large effect sizes. Group differences were non-significant for rest of the outcomes(i.e. latency to fall asleep, minutes awake in middle of night and minutes awake too early). Individualized homeopathy seemed to produce significantly better effect than placebo. Independent replications and adequately powered trials with enhanced methodological rigor are warranted.

I have studied this article in some detail; its methodology is nicely and fully described in the original paper. To my amazement, I cannot find a flaw that is worth mentioning. Sure, the sample was small, the treatment time short, the outcome measure subjective, the paper comes from a dubious journal, the authors have a clear conflict of interest, even though they deny it – but none of these limitations has the potential to conclusively explain the positive result.

In view of what I stated above and considering what the clinical evidence so far tells us, this is most puzzling.

A 2010 systematic review authored by proponents of homeopathy included 4 RCTs comparing homeopathic medicines to placebo. All involved small patient numbers and were of low methodological quality. None demonstrated a statistically significant difference in outcomes between groups.

My own 2011 not Medline-listed review (Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies Volume 16(3) September 2011 195–199) included several additional studies. Here is its abstract:

The aim of this review was the critical evaluation of evidence for the effectiveness of homeopathy for insomnia and sleep-related disorders. A search of MEDLINE, AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register was conducted to find RCTs using any form of homeopathy for the treatment of insomnia or sleep-related disorders. Data were extracted according to pre-defined criteria; risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane criteria. Six randomised, placebo-controlled trials met the inclusion criteria. Two studies used individualised homeopathy, and four used standardised homeopathic treatment. All studies had significant flaws; small sample size was the most prevalent limitation. The results of one study suggested that homeopathic remedies were superior to placebo; however, five trials found no significant differences between homeopathy and placebo for any of the main outcomes. Evidence from RCTs does not show homeopathy to be an effective treatment for insomnia and sleep-related disorders.

It follows that the new trial contradicts previously published evidence. In addition, it clearly lacks plausibility, as the remedies used were highly diluted and therefore should be pure placebos. So, what could be the explanation of the new, positive result?

As far as I can see, there are the following possibilities:

- fraud,

- coincidence,

- some undetected/undisclosed bias,

- homeopathy works after all.

I would be most grateful, if someone could help solving this puzzle for me (if needed, I can send you the full text of the new article for assessment).

Doubtlessly, you will have noted that homeopathy missed out yet again at this year’s Nobels. Personally, I am convinced that this is all due to the evil propaganda put about by malicious sceptics (paid lavishly by BIG PHARMA, of course). But all is not lost! Down under, ‘CHOICE’ do know what is truly prize-worthy!

The Australian Consumers’ Association ‘CHOICE’ reviews everyday items like aspirin, detergents and instant coffee – but also major purchases like cars and washing machines. Each year, CHOICE awards ‘SHONKIES’ (from ‘shonky‘ = dishonest, unreliable, or illegal, especially in a devious way). CHOICE receive hundreds of nominations for Shonky products and services from CHOICE members and staff. While some Shonky nominees may not be breaking laws or breaching regulations – though sometimes they are – they believe that consumers deserve better products and services.

And how do they decide which nominations make the cut?

First and foremost, a nomination has to meet one or more of the following Shonky criteria:

- Fails a standard

- Poor performance on CHOICE tests

- Hidden charges

- Lack of transparency

- False claims or broken promises

- Consumers are worse off because of it

- Consumer confusion

- Poor value for money

- Consumer frustration, or just plain outrage

Products that meet one or more of these criteria make it to the short list. From there CHOICE look at how the issue will resonate with consumers, as well as government authorities and the media, which have the power to prod companies to pick up their act.

This year, CHOICE awarded 7 shonkies. My favourite, of course, is the award for trickery that leaves people sleepless – here is what CHOICE tell us about it:

Big pharmaceutical companies, or ‘big pharma’, are synonymous with big medical production, big money and a big impact on the type of healthcare products we can access. One thing that’s rarely expected from big pharma is homeopathic cures, which are more typically found in the domain of alternative therapies.

However, at least one big pharma company in Australia is selling homeopathic products on a very large scale. Pharmacare, which boasts on LinkedIn that it’s “the largest private, Australian-owned consumer health, fitness and consumer goods company in the country”, currently operates 23 brands, including Bioglan. According to their website, their products are available in “5200 pharmacies, 3000 supermarket outlets, department and variety stores nationwide, and hundreds of overseas outlets in Asia, America and Europe.”

In 2017, we awarded Bioglan and another Pharmacare brand, Nature’s Way, a Shonky for its outrageous claims that sticky, sugary lollies are in fact good for teeth. This year, Pharmacare and Bioglan receive another dubious honour for its over-the-counter Melatonin Homeopathic Sleep Formula. While melatonin (currently a prescription-only medicine in Australia) is known to promote sleep and is used to help people suffering jet lag or sleep disorders, there’s no reliable evidence that homeopathic melatonin (or homeopathic products in general) has any effect other than as a placebo. Despite this, the company makes the claim that Bioglan Melatonin helps “relieve mild temporary insomnia and symptoms of mild nervous tension”.

Bioglan’s Melatonin Homeopathic Sleep Formula is also available in chewable tablet form or spray and both products promise to “relieve mild temporary insomnia”.

On the product’s web page, we’re told “results depend on how often the homeopathic remedy is taken, not on the quantity used”, because in homeopathy, “the amount consumed is not relevant, children are treated in the same way as adults”.

However, directions for the tablet version state, “To aid sleep: Chew 3-5 tablets half an hour before bedtime”, while the spray is “rapidly absorbed to start working quickly”.

To be fair to Bioglan, consuming more does support the primary reason for this product’s existence – the more tablets people chew, the sooner they’ll potentially cough up another $24.50 (RRP).

Melatonin Homeopathic Sleep Formula is packaged like medication and sold in a pharmacy. But with murky claims that are not supported with evidence, wasting money is the only area where this product is proven to be effective. Not only does Bioglan Melatonin not help you sleep, it’s Shonky enough that you might lose sleep worrying about the brazen trickery this company gets away with.

END OF QUOTE

As I said, it’s not a Nobel, but it’s certainly a start.

My heart-felt congratulations to homeopaths across the world!

Insomnia is a ‘gold standard’ indication for alternative therapies of all types. In fact, it is difficult to find a single of these treatments that are not being touted for this indication. Consequently, it has become a nice little earner for alternative therapists (hence ‘gold standard’).

But how good is the evidence suggesting that any alternative therapy is effective for insomnia?

Whenever I have discussed this issue on my blog, the conclusion was that the evidence is less than convincing or even negative. Similarly, whenever I conducted proper systematic reviews in this area, the evidence turned out to be weak or negative. Here are four of the conclusions we drew at the time:

- The evidence for acupuncture as a treatment of insomnia is plagued by important limitations, e.g. the poor quality of most primary studies and some systematic reviews. Those that are sensitive to such limitations, fail to arrive at a positive verdict about the effectiveness of acupuncture.

- We conclude that, because of the paucity and of the poor quality of the data, the evidence for the effectiveness of auricular acupuncture for the symptomatic treatment of insomnia is limited. Further, rigorously designed trials are warranted to confirm these results.

- The evidence for valerian as a treatment for insomnia is inconclusive.

- Evidence from RCTs does not show homeopathy to be an effective treatment for insomnia and sleep-related disorders. (FACT, 2011, 16:195-99)

“But this ERNST fellow cannot be trusted, he is not objective!”, I hear some of my detractors shout.

But is he really?

Would an independent, high-level panel of experts arrive at more positive conclusions?

Let’s find out!

This European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia recently provided recommendations for the management of adult patients with insomnia. The guideline is based on a systematic review of relevant meta-analyses published till June 2016. The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system was used to grade the evidence and guide recommendations.

The findings and recommendations are as follows:

- Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia is recommended as the first-line treatment for chronic insomnia in adults of any age (strong recommendation, high-quality evidence).

- A pharmacological intervention can be offered if cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia is not sufficiently effective or not available. Benzodiazepines, benzodiazepine receptor agonists and some antidepressants are effective in the short-term treatment of insomnia (≤4 weeks; weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence). Antihistamines, antipsychotics, melatonin and phytotherapeutics are not recommended for insomnia treatment (strong to weak recommendations, low- to very-low-quality evidence).

- Light therapy and exercise need to be further evaluated to judge their usefulness in the treatment of insomnia (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).

- Complementary and alternative treatments (e.g. homeopathy, acupuncture) are not recommended for insomnia treatment (weak recommendation, very-low-quality evidence).

I think, I can rest my case.

Of all alternative treatments, aromatherapy (i.e. the application of essential oils to the body, usually by gentle massage or simply inhalation) seems to be the most popular. This is perhaps understandable because it certainly is an agreeable form of ‘pampering’ for someone in need of come TLC. But is aromatherapy more than that? Is it truly a ‘THERAPY’?

A recent systematic review was aimed at evaluating the existing data on aromatherapy interventions as a means of improving the quality of sleep. Electronic literature searches were performed to identify relevant studies published between 2000 and August 2013. Randomized controlled and quasi-experimental trials that included aromatherapy for the improvement of sleep quality were considered for inclusion. Of the 245 publications identified, 13 studies met the inclusion criteria, and 12 studies could be used for a meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis of the 12 studies revealed that the use of aromatherapy was effective in improving sleep quality. Subgroup analysis showed that inhalation aromatherapy was more effective than aromatherapy applied via massage.

The authors concluded that readily available aromatherapy treatments appear to be effective and promote sleep. Thus, it is essential to develop specific guidelines for the efficient use of aromatherapy.

Perfect! Let’s all rush out and get some essential oils for inhalation to improve our sleep (remarkably, the results imply that aroma therapists are redundant!).

Not so fast! As I see it, there are several important caveats we might want to consider before spending our money this way:

- Why did this review focus on such a small time-frame? (Systematic reviews should include all the available evidence of a pre-defined quality.)

- The quality of the included studies was often very poor, and therefore the overall conclusion cannot be definitive.

- The effect size of armoatherapy is small. In 2000, we published a similar review and concluded that aromatherapy has a mild, transient anxiolytic effect. Based on a critical assessment of the six studies relating to relaxation, the effects of aromatherapy are probably not strong enough for it to be considered for the treatment of anxiety. The hypothesis that it is effective for any other indication is not supported by the findings of rigorous clinical trials.

- It seems uncertain which essential oil is best suited for this indication.

- Aromatherapy is not always entirely free of risks. Another of our reviews showed that aromatherapy has the potential to cause adverse effects some of which are serious. Their frequency remains unknown. Lack of sufficiently convincing evidence regarding the effectiveness of aromatherapy combined with its potential to cause adverse effects questions the usefulness of this modality in any condition.

- There are several effective ways for improving sleep when needed; we need to know how aromatherapy compares to established treatments for that indication.

All in all, I think stronger evidence is required that aromatherapy is more that pampering.

ENOUGH SAID?