Monthly Archives: February 2018

Lock 10 bright people into a room and tell them they will not be let out until they come up with the silliest idea in healthcare. It is not unlikely, I think, that they might come up with the concept of visceral osteopathy.

In case you wonder what visceral osteopathy (or visceral manipulation) is, one ‘expert’ explains it neatly: Visceral Osteopathy is an expansion of the general principles of osteopathy which includes a special understanding of the organs, blood vessels and nerves of the body (the viscera). Visceral Osteopathy relieves imbalances and restrictions in the interconnections between the motions of all the organs and structures of the body. Jean-Piere Barral RPT, DO built on the principles of Andrew Taylor Still DO and William Garner Sutherland DO, to create this method of detailed assessment and highly specific manipulation. Those who wish to practice Visceral Osteopathy train intensively through a series of post-graduate studies. The ability to address the specific visceral causes of somatic dysfunction allows the practitioner to address such conditions as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), irritable bowel (IBS), and even infertility caused by mechanical restriction.

But, as I have pointed out many times before, the fact that a treatment is based on erroneous assumptions does not necessarily mean that it does not work. What we need to decide is evidence. And here we are lucky; a recent paper provides just that.

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify and critically appraise the scientific literature concerning the reliability of diagnosis and the clinical efficacy of techniques used in visceral osteopathy.

Only inter-rater reliability studies including at least two raters or the intra-rater reliability studies including at least two assessments by the same rater were included. For efficacy studies, only randomized-controlled-trials (RCT) or crossover studies on unhealthy subjects (any condition, duration and outcome) were included. Risk of bias was determined using a modified version of the quality appraisal tool for studies of diagnostic reliability (QAREL) in reliability studies. For the efficacy studies, the Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to assess their methodological design. Two authors performed data extraction and analysis.

Extensive searches located 8 reliability studies and 6 efficacy trials that could be included in this review. The analysis of reliability studies showed that the diagnostic techniques used in visceral osteopathy are unreliable. Regarding efficacy studies, the least biased study showed no significant difference for the main outcome. The main risks of bias found in the included studies were due to the absence of blinding of the examiners, an unsuitable statistical method or an absence of primary study outcome.

The authors (who by the way declared no conflicts of interest) concluded that the results of the systematic review lead us to conclude that well-conducted and sound evidence on the reliability and the efficacy of techniques in visceral osteopathy is absent.

It is hard not to appreciate the scientific rigor of this review or to agree with the conclusions drawn by the French authors.

But what consequences should we draw from all this?

The authors of this paper state that more and better research is needed. Somehow, I doubt this. Visceral osteopathy is not plausible and the best evidence available to date does not show it works. In my view, this means that we should declare it an obsolete aberration of medical history.

To this, the proponents of visceral osteopathy will probably say that they have tons of experience and have witnessed wonderful cures etc. This I do not doubt; however, the things they saw were not due to the effects of visceral osteopathy, they were due to chance, placebo, regression towards the mean, the natural history of the diseases treated etc., etc. And sometimes, experience is nothing more that the ability to repeat a mistake over and over again.

- If it looks like a placebo,

- if it behaves like a placebo,

- if it tests like a placebo,

IT MOST LIKELY IS A PLACEBO!!!

And what is wrong with a placebo, if it helps patients?

GIVE ME A BREAK!

WE HAVE ALREADY DISCUSSED THIS AD NAUSEAM. JUST READ SOME OF THE PREVIOUS POSTS ON THIS SUBJECT.

The ‘European Scientific Cooperative on Anthroposophic Medicinal Products‘ claim that there is a need for a regulatory framework for anthroposophic medicinal products (AMPs) in Europe. The existing regulatory requirements for conventional medicinal products are not appropriate for AMPs. Special registration procedures exist in some countries for homeopathic products and in the European Union for herbal products. However, these procedures only apply to a proportion of AMPs and the particular properties of AMPs are only in part accounted for. Suitable registration procedures especially for AMPs exist only in Germany and Switzerland.

The European Commission has acknowledged the existence of therapy systems, whose products have no adequate regulation, and it has proposed that the suitability of a separate legal framework for products of certain traditions such as Anthroposophic Medicine should be assessed. This statement should be seen in the context of developments in international trade, whereby representatives of therapy systems such as Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda wish to market their products in Europe.

It seems obvious that the safety of AMPs must be demonstrated, if regulators are to comply with the wishes of the AMP-industry. In other words, they require evidence. As luck has it, a recent paper provides just what they need.

The main objective of this analysis was to determine the frequency of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) to AMPs, relative to the number of AMP prescriptions.

The researchers conducted a prospective pharmacovigilance study with the patients of physicians in outpatient care in Germany. Diagnoses and prescriptions were extracted from the electronic medical records. A total of 38 German physicians trained in AM were asked to link all AMP prescriptions to the respective indications (diagnoses), and to document all serious ADRs as well as all ADRs of intensity III–IV. In addition, a subgroup of 7 ‘prescriber physicians’ agreed to also document all non-serious ADRs of any intensity. The study was conducted under routine care conditions with ADRs identified at ordinary follow-up consultations, without any additional scheduled follow-up visits. Physicians were remunerated with 15 Euro for each ADR report but not for their regular participation; patients received no remuneration. Patients were eligible for this analysis, if they had one or more AMP prescription in the years 2001–2010, followed by one or more physician visit.

A total of 44,662 patients with 311,731 AMP prescriptions, comprising 1722 different AMPs, were included. One hundred ADRs to AMPs occurred, caused by 83 different AMPs. ADR intensity was mild, moderate, and severe in 50% (n = 50/100), 43%, and 7% of cases, respectively; one ADR was serious. ADRs of any intensity occurred in 0.071% (n = 67/94,734) of AMP prescriptions and in 0.502% (n = 65/12,956) of patients prescribed AMPs. The highest ADR frequency was 0.290% of prescriptions for one specific AMP. Among all patients, serious ADRs occurred in 0.0003% (n = 1/311,731) of prescriptions and 0.0022% (n = 1/44,662) of patients.

The authors concluded that in this analysis from a large sample, ADRs to AMP therapy in outpatient care were rare; ADRs of high intensity as well as serious ADRs were very rare.

Most AMPs are highly diluted, and therefore, one would not expect frequent or serious ADRs. Yet, I still find these incidence figures mysterious. The reason is simple: even the ARDs of pure placebos (such as most AMPs) are known to be much more frequent. In other words, the nocebo-effects of drugs are much more common than these results seem to reflect.

This, I think, leads to one of two possible conclusions:

- AMPs are somehow miraculously exempt from the known facts of ADRs.

- There is something fundamentally wrong with this study.

I let you decide which is the case.

Oh, I almost forgot. At the end of this paper there is a not unimportant note:

The EvaMed study was funded by the Software AG-Stiftung. This analysis and publication was commissioned by the European Scientific Cooperative on Anthroposophic Medicinal Products (http://www.escamp.org) with financial support from foundations (Christophorus-Stiftung, Damus-Donata-Stiftung, Ekhagastiftelsen, Mahle-Stiftung, Software AG-Stiftung) and manufacturers (Wala, Weleda). The sponsors had no influence on the planning or conduct of the EvaMed study; the collection, preparation, analysis or interpretation of data for this paper; nor on the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

“MDs do not make false claims HAHAHA.”

This is from a comment I recently received on this blog.

It made me think.

Yes, of course, MDs do not always reveal the full truth to their patients; sometimes they might even tell lies (in this post, I shall use the term ‘lies’ for any kind of untruth).

So, what about these lies?

The first thing to say about them is obvious: THEY CAN NEVER JUSTIFY THE LIES OF OTHERS.

- the lies of the Tories cannot justify the lies of Labour party members,

- the lies of a plaintiff in court cannot justify any lies of the defendant,

- the lies of MDs cannot justify the lies of alternative practitioners.

The second thing to say about the lies of MDs is that, in my experience, most are told in the desire to protect patients. In some cases, this may be ill-advised or ethically questionable, but the motivation is nevertheless laudable.

- I might not tell the truth when I say (this really should be ‘said’, because I have not treated patients for many years) THIS WILL NOT HURT AT ALL. In the end, it hurt quite a bit but we all understand why I lied.

- I might claim that this treatment is sure to work (knowing full well that such a prediction is impossible), but we all know that I said so in order to maximise my patient’s compliance and expectation in order to generate the best possible outcome.

- I might dismiss a patient’s fear that his condition is incurable (while strongly suspecting that it is), but I would do this to improve his anxiety and well-being.

Yet, these are not the type of lies my commentator referred to. In fact, he provided a few examples of the lies MDs tell, in his opinion. He claimed that:

- They tell them that diabetes is not curable. False claim

- They compare egg intake with smoking on their affect to your health. False claim

- They say arthroscopic surgery of the knee is beneficial. False claim

- They state that surgery, chemo, and radiation is the only treatment for cancer. False claim

- They say that family association is the cause of most inflammatory conditions. False claim

I don’t want to go into the ‘rights or wrongs’ of these claims (mostly wrongs, as far as I can see). Instead, I would argue that any MD who makes a claim that is wrong behaves unethical and should retrain. If he erroneously assumes the claim to be correct, he is not fully informed (which, of course is unethical in itself) and needs to catch up with the current best evidence. If he makes a false claim knowing that it is wrong, he behaves grossly unethical and must justify himself in front of his professional disciplinary committee.

As this blog focusses on alternative medicine, let’s briefly consider the situation in that area. The commentator made his comments in connection to a post about chiropractic, so let’s look at the situation in chiropractic.

- Do many chiropractors claim to be able to treat a wide array of conditions without good evidence?

- Do they misadvise patients about conventional treatments, such as vaccinations?

- Do they claim that their spinal manipulations are safe?

- Do they tell patients they need regular ‘maintenance treatment’ to stay healthy?

- Do they claim to be able to diagnose subluxations?

- Do they pretend that subluxations cause illness and disease?

- Do they claim to adjust subluxations?

If you answered several of these questions with YES, I probably have made my point.

On reflection, it turns out that clinicians of all types do tell lies. Some are benign/white lies and others are fundamental, malignant lies. Most of us probably agree that the former category is largely negligible. The latter category can, however, be serious. In my experience, it is hugely more prevalent in the realm of alternative medicine. When it occurs in conventional medicine, appropriate measures are in place to prevent reoccurrence. When it occurs in alternative medicine, nobody seems to bat an eyelash.

My conclusion from these random thoughts: the truth is immeasurably valuable, and lies can be serious and often are damaging to patients. Therefore, we should always pursue those who tell serious lies, no matter whether they are MDs or alternative practitioners.

By guest blogger Norbert Aust

The Germany based Informationsnetzwerk Homöopathie (“Information network Homeopathy”, INH) is a group of critics of homeopathy, with doctors, pharmacists, and other scientists as members.

Among other activities we are running a few websites to provide sound information not so much to the academic but to the more layman public and patients on what homeopathy really is all about. This should counterbalance the very positive impressions created by promotion and marketing activities of providers of homeopathic services, that is, manufacturers, pharmacies and practitioners. We want to offer some reliable source of information which otherwise is seldom to be found in Germany. And we want to strip homeopathy of its reputation of being an effective therapy – and of course have it banned from pharmacies, universities and public health insurance. But this is another issue.

More than once we were asked if our pages were available in English – and now we are happy to announce that we started to transcribe some of our content. We – that is Udo Endruscheit, Sven Rudloff and myself – are working on that project one piece at a time. We started with a series of quite new articles originally published in German about the FAQs that can be found on the website of the Homeopathic Research Institute (HRI). We feel, this might be of interest for some of the English readers too. As these FAQs are available in more than just English or German, HRI seems to try to set some standard of arguments to rebuke their critics and provide arguments in favour of homeopathy – with some doubtful, some very doubtful and many outright wrong points. (BTW: If someone feels inclined to translate our English (or German) versions to yet another language, please proceed. Just give us credit and let us have some link to the site where you publish the translation.)

You may find our articles on two of our sites, namely the INH-website for just reading and my blog, where you can comment and discuss them. In the future, my blog will contain a more in depth analysis and the INH-website will provide a more easy to read version – but this is to be in the future.

Here are the links:

HRI FAQ #1: There is no evidence my blog; INH-Website.

HRI FAQ #2: No good positive trials my blog; INH-Website.

HRI FAQ #3: It’s impossible my blog; INH-Website.

In future, all my English articles will be found here but right now there are only the three listed above.

This of course is work in process and sooner – or more probable later – all our articles that we feel may find interest with a more international public will be translated into English. However, if any of you readers would want to have a special article of ours translated at once, please feel free to contact me by commenting on my blog or by email (dr.norbert.aust(at)t(minus)online(dot)de – just drop the dots before the (at) and replace what is in brackets with the proper signs).

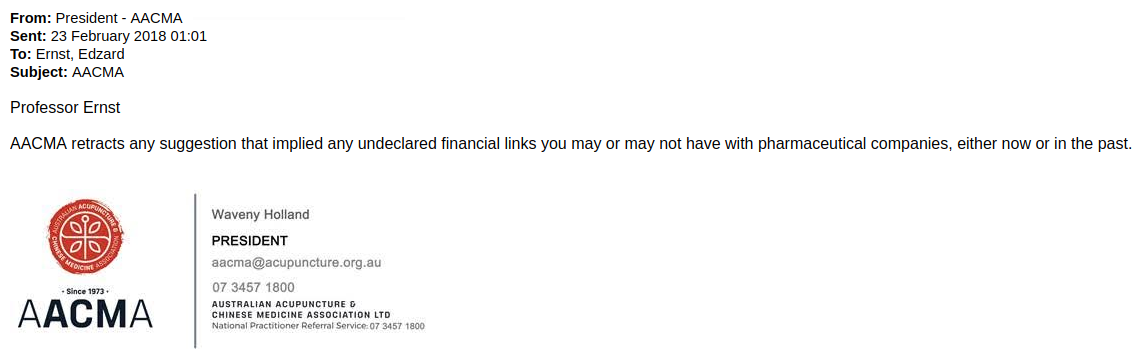

I have to admit that I had little hope it would come. But after sending my ‘open letter’ twice to their email address, I have just received this:

As you might remember, the AACMA had accused me of an pecuniary undeclared link with the pharmaceutical industry. Their claim was based on me having been the editor of a journal, FACT, which was co-published by the British Pharmaceutical Society (BPS). When I complained and the AACMA learnt that the journal had been discontinued, they retracted their claim but carried on distributing the allegation that I had formerly had an undeclared conflict of interest. When they finally understood that the BPS was not the pharmaceutical industry (all it takes is a simple Google search), and after me complaining again and again, they sent me the above email.

The full details of this sorry story are here and here.

So, the AACMA have done the right thing?

Yes and no!

The have retracted their repeated lies.

But they have not done this publicly as requested (this is partly the reason for me writing this post to make their retraction public).

More importantly, they have not apologised !!!

Why should they, you might ask.

- Because they have (tried to) damage my reputation as an independent scientist.

- Because they have not done their research before making and insisting on a far-reaching claim.

- Because they have shown themselves too stupid to grasp even the most elementary issues.

By not apologising, they have, I find, shown how unprofessional they really are, and how much they lack simple human decency. On their website, the AACMA state that “since 1973, AACMA has represented the profession and values high standards in ethical and professional practice.” Personally, I think that their standards in ethical and professional practice are appalling.

Yesterday, a press-release about our new book has been distributed by our publisher. As I hope than many regular readers of my blog might want to read this book – if you don’t want to buy it, please get it via your library – I decided to re-publish the press-release here:

Yesterday, a press-release about our new book has been distributed by our publisher. As I hope than many regular readers of my blog might want to read this book – if you don’t want to buy it, please get it via your library – I decided to re-publish the press-release here:

Governments must legislate to regulate and restrict the sale of complementary and alternative therapies, conclude authors of new book More Harm Than Good.

Heidelberg, 20 February 2018

Commercial organisations selling lethal weapons or addictive substances clearly exploit customers, damage third parties and undermine genuine autonomy. Purveyors of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) do too, argue authors Edzard Ernst and Kevin Smith.

The only downside to regulating such a controversial industry is that regulation could confer upon it an undeserved stamp of respectability and approval. At best, it can ensure the competent delivery of therapies that are inherently incompetent.

This is just one of the ethical dilemmas at the heart of the book. In all areas of healthcare, consumers are entitled to expect essential elements of medical ethics to be upheld. These include access to competent, appropriately-trained practitioners who base treatment decisions on evidence from robust scientific research. Such requirements are frequently neglected, ignored or wilfully violated in CAM.

“We would argue that a competent healthcare professional should be defined as one who practices or recommends plausible therapies that are supported by robust evidence,” says bioethicist Kevin Smith.

“Regrettably, the reality is that many CAM proponents allow themselves to be deluded as to the efficacy or safety of their chosen therapy, thus putting at risk the health of those who heed their advice or receive their treatment,” he says.

Therapies covered include homeopathy, acupuncture, chiropractic, iridology, Reiki, crystal healing, naturopathy, intercessory prayer, wet cupping, Bach flower therapy, Ukrain and craniosacral therapy. Their inappropriate use can not only raises false hope and inflicts financial hardship on consumers, but can also be dangerous; either through direct harm or because patients fail to receive more effective treatment. For example, advice given by homeopaths to diabetic patients has the potential to kill them; and when anthroposophic doctors advise against vaccination, they can be held responsible for measles outbreaks.

There are even ethical concerns to subjecting such therapies to clinical research. In mainstream medical research, a convincing database from pre-clinical research is accumulated before patients are experimented upon. However, this is mostly not possible with CAM. Pre-scientific forms of medicine have been used since time immemorial, but their persistence alone does not make them credible or effective. Some are based on notions so deeply implausible that accepting them is tantamount to believing in magic.

“Dogma and ideology, not rationality and evidence, are the drivers of CAM practice,” says Professor Edzard Ernst.

Edzard Ernst, Kevin Smith

More Harm than Good?

1st ed. 2018, XXV, 223 p.

Softcover $22.99, €19,99, £15.99 ISBN 978-3-319-69940-0

Also available as an eBook ISBN 978-3-319-69941-7

END OF PRESS RELEASE

As I already stated above, I hope you will read our new book. It offers something that has, I think, not been attempted before: it critically evaluates many aspects of alternative medicine by holding them to the ethical standards of medicine. Previously, we have often been asking WHERE IS THE EVIDENCE FOR THIS OR THAT CLAIM? In our book, we ask different questions: IS THIS OR THAT ASPECT OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE ETHICAL? Of course, the evidence question does come into this too, but our approach in this book is much broader.

The conclusions we draw are often surprising, sometimes even provocative.

Well, you will see for yourself (I hope).

The chiropractor Oakley Smith had graduated under D D Palmer in 1899. Smith was a former Iowa medical student who also had investigated Andrew Still’s osteopathy in Kirksville, before going to Palmer in Davenport. Eventually, Smith came to reject the Palmer concept of vertebral subluxation and developed his own concept of “the connective tissue doctrine” or naprapathy. Today, naprapathy is a popular form of manual therapy, particularly in Scandinavia and the US.

But what exactly is naprapathy? This website explains it quite well: Naprapathy is defined as a system of specific examination, diagnostics, manual treatment and rehabilitation of pain and dysfunction in the neuromusculoskeletal system. The therapy is aimed at restoring function through treatment of the connective tissue, muscle- and neural tissues within or surrounding the spine and other joints. Naprapathic treatment consists of combinations of manual techniques for instance spinal manipulation and mobilization, neural mobilization and Naprapathic soft tissue techniques, in additional to the manual techniques Naprapaths uses different types of electrotherapy, such as ultrasound, radial shockwave therapy and TENS. The manual techniques are often combined with advice regarding physical activity and ergonomics as well as medical rehabilitation training in order to decrease pain and disability and increase work ability and quality of life. A Dr. of Naprapathy is specialized in the diagnosis of structural and functional neuromusculoskeletal disorders, treatment and rehabilitation of patients with problems of such origin as well as to differentiate pain of other origin.

DOCTOR OF NAPRAPATHY? I hear you shout.

Yes, in the US, the title exists: The National College of Naprapathic Medicine is chartered by the State of Illinois and recognized by the State Board of Higher Education to grant the degree, Doctor of Naprapathy (D.N.). Graduates of the College are eligible to take the Naprapathic Medicine examination for licensure in the State of Illinois. The D.N. Degree requires:

- 66 hours – Basic Sciences

- 64 hours – Naprapathic Sciences

- 60 hours – Clinical Internship

Things become even stranger when we ask, what does the evidence show?

I found all of three clinical trials on Medline.

A 2016 clinical trial was designed to compare the treatment effect on pain intensity, pain related disability and perceived recovery from a) naprapathic manual therapy (spinal manipulation, spinal mobilization, stretching and massage) to b) naprapathic manual therapy without spinal manipulation and to c) naprapathic manual therapy without stretching for male and female patients seeking care for back and/or neck pain.

Participants were recruited among patients, ages 18-65, seeking care at the educational clinic of Naprapathögskolan – the Scandinavian College of Naprapathic Manual Medicine in Stockholm. The patients (n = 1057) were randomized to one of three treatment arms a) manual therapy (i.e. spinal manipulation, spinal mobilization, stretching and massage), b) manual therapy excluding spinal manipulation and c) manual therapy excluding stretching. The primary outcomes were minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity and pain related disability. Treatments were provided by naprapath students in the seventh semester of eight total semesters. Generalized estimating equations and logistic regression were used to examine the association between the treatments and the outcomes.

At 12 weeks follow-up, 64% had a minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity and 42% in pain related disability. The corresponding chances to be improved at the 52 weeks follow-up were 58% and 40% respectively. No systematic differences in effect when excluding spinal manipulation and stretching respectively from the treatment were found over 1 year follow-up, concerning minimal clinically important improvement in pain intensity (p = 0.41) and pain related disability (p = 0.85) and perceived recovery (p = 0.98). Neither were there disparities in effect when male and female patients were analyzed separately.

The authors concluded that the effect of manual therapy for male and female patients seeking care for neck and/or back pain at an educational clinic is similar regardless if spinal manipulation or if stretching is excluded from the treatment option.

Even though this study is touted as showing that naprapathy works by advocates, in all honesty, it tells us as good as nothing about the effect of naprapathy. The data are completely consistent with the interpretation that all of the outcomes were to the natural history of the conditions, regression towards the mean, placebo, etc. and entirely unrelated to any specific effects of naprapathy.

A 2010 study by the same group was to compare the long-term effects (up to one year) of naprapathic manual therapy and evidence-based advice on staying active regarding non-specific back and/or neck pain.

Subjects with non-specific pain/disability in the back and/or neck lasting for at least two weeks (n = 409), recruited at public companies in Sweden, were included in this pragmatic randomized controlled trial. The two interventions compared were naprapathic manual therapy such as spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage and stretching, (Index Group), and advice to stay active and on how to cope with pain, provided by a physician (Control Group). Pain intensity, disability and health status were measured by questionnaires.

89% completed the 26-week follow-up and 85% the 52-week follow-up. A higher proportion in the Index Group had a clinically important decrease in pain (risk difference (RD) = 21%, 95% CI: 10-30) and disability (RD = 11%, 95% CI: 4-22) at 26-week, as well as at 52-week follow-ups (pain: RD = 17%, 95% CI: 7-27 and disability: RD = 17%, 95% CI: 5-28). The differences between the groups in pain and disability considered over one year were statistically significant favoring naprapathy (p < or = 0.005). There were also significant differences in improvement in bodily pain and social function (subscales of SF-36 health status) favoring the Index Group.

The authors concluded that combined manual therapy, like naprapathy, is effective in the short and in the long term, and might be considered for patients with non-specific back and/or neck pain.

This study is hardly impressive either. The results are consistent with the interpretation that the extra attention and care given to the index group was the cause of the observed outcomes, unrelated to ant specific effects of naprapathy.

The last study was published in 2017 again by the same group. It was designed to compare naprapathic manual therapy with evidence-based care for back or neck pain regarding pain, disability, and perceived recovery.

Four hundred and nine patients with pain and disability in the back or neck lasting for at least 2 weeks, recruited at 2 large public companies in Sweden in 2005, were included in this randomized controlled trial. The 2 interventions were naprapathy, including spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage, and stretching (Index Group) and support and advice to stay active and how to cope with pain, according to the best scientific evidence available, provided by a physician (Control Group). Pain, disability, and perceived recovery were measured by questionnaires at baseline and after 3, 7, and 12 weeks.

At 7-week and 12-week follow-ups, statistically significant differences between the groups were found in all outcomes favoring the Index Group. At 12-week follow-up, a higher proportion in the naprapathy group had improved regarding pain [risk difference (RD)=27%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 17-37], disability (RD=18%, 95% CI: 7-28), and perceived recovery (RD=44%, 95% CI: 35-53). Separate analysis of neck pain and back pain patients showed similar results.

At 7-week and 12-week follow-ups, statistically significant differences between the groups were found in all outcomes favoring the Index Group. At 12-week follow-up, a higher proportion in the naprapathy group had improved regarding pain [risk difference (RD)=27%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 17-37], disability (RD=18%, 95% CI: 7-28), and perceived recovery (RD=44%, 95% CI: 35-53). Separate analysis of neck pain and back pain patients showed similar results.

The authors thought that this trial suggests that combined manual therapy, like naprapathy, might be an alternative to consider for back and neck pain patients.

As the study suffers from the same limitations as the one above (in fact, it might be a different analysis of the same trial), they might be mistaken. I see no good reason to assume that any of the three studies provide good evidence for the effectiveness of naprapathy.

So, what should we conclude from all this?

If you ask me, naprapathy is something between chiropractic (without some of the woo) and physiotherapy (without its expertise). There is no good evidence that it works. Crucially, there is no evidence that it is superior to other therapeutic options.

I was going to finish on a positive note stating that ‘at least the ‘naprapathologists’ (I refuse to even consider the title of ‘doctor of naprapathy’) do not claim to treat conditions other than musculoskeletal problems’. But then I found this advertisement of a ‘naprapathologist’ on Twitter:

And now, I am going to finish by stating that A LOT OF NAPRAPATHY LOOKS VERY MUCH LIKE QUACKERY TO ME.

Sipjeondaebo-tang is an East Asian herbal supplement containing Angelica root (Angelicae Gigantis Radix), the rhizome of Cnidium officinale Makino (Cnidii Rhizoma), Radix Paeoniae, Rehmannia glutinosa root (Rehmanniae Radix Preparata), Ginseng root (Ginseng Radix Alba), Atractylodes lancea root (Atractylodis Rhizoma Alba), the dried sclerotia of Poria cocos (Poria cocos Sclerotium), Licorice root (Glycyrrhizae Radix), Astragalus root (Astragali Radix), and the dried bark of Cinnamomum verum (Cinnamomi Cortex).

But does this herbal mixture actually work? Korean researchers wanted to find out.

The purpose of their study was to examine the feasibility of Sipjeondaebo-tang (Juzen-taiho-to, Shi-Quan-Da-Bu-Tang) for cancer-related anorexia. A total of 32 participants with cancer anorexia were randomized to either Sipjeondaebo-tang group or placebo group. Participants were given 3 g of Sipjeondaebo-tang or placebo 3 times a day for 4 weeks. The primary outcome was a change in the Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale of Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT). The secondary outcomes included Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of anorexia, FAACT scale, and laboratory tests.

The results showed that anorexia and quality of life measured by FAACT and VAS were improved after 4 weeks of Sipjeondaebo-tang treatment. However, there was no significant difference between changes of Sipjeondaebo-tang group and placebo group.

From this, the authors of the study concluded that sipjeondaebo-tang appears to have potential benefit for anorexia management in patients with cancer. Further large-scale studies are needed to ensure the efficacy.

Well, isn’t this just great? Faced with a squarely negative result, one simply ignores it and draws a positive conclusion!

As we all know – and as trialists certainly must know – controlled trials are designed to compare the outcomes of two groups. Changes within one of the groups can be caused by several factors unrelated to the therapy and are therefore largely irrelevant. This means that “no significant difference between changes of Sipjeondaebo-tang group and placebo group” indicates that the herbal mixture had no effect. In turn this means that a conclusion stating that “sipjeondaebo-tang appears to have potential benefit for anorexia” is just fraudulent.

This level of scientific misconduct is remarkable, even for the notoriously poor Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

I strongly suggest that:

- The journal is de-listed from Medline because similarly misleading nonsense has been coming out of this rag for some time.

- The paper is withdrawn because it can only mislead vulnerable patients.

I was reliably informed that the ‘Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association’ (AACMA) are currently – that is AFTER having retracted the falsehoods they previously issued about me – distributing a document which contains the following passage:

It is noted that Mr Ernst derives income from editing a journal called Focus on Alternative and Complementary Medicine which is published by the British Pharmaceutical Society and listed in pharamcologyjournals.com. Ernst has not declared his own pecuniary conflicts of interest and links with the pharmaceutical industry. I note that the FSM webpage declares that:

‘None of the members of the executive has any vested interests in pharmaceutical companies such that our views or opinions might be influenced’.

This statement is disingenuous and deceptive if instead you base your critique on the blog of a person with such pharmaceutical interests without declaring it.

This is a repetition of the lies which the AACMA have already retracted (see comments section of my previous post on this matter). In my view, this is highly dishonest and actionable. For this reason, I today sent them this ‘open letter’ which I also publish here:

Dear Madam/Sir,

As explained more fully in this blog-post, you have recently accused me of undeclared links to and payments from the pharmaceutical industry. This is a serious, potentially liable allegation.

My objections were followed by your retraction of these allegations (see the comments section of my above-mentioned blog-post). However, your retraction displays an embarrassing level of ignorance and contains several grave errors (see the comments section of my above-mentioned blog-post). Crucially, it implies that I formerly had an undeclared conflict of interest. This is untrue. More importantly, you currently distribute a document that continues to allege that I currently have ‘pharmaceutical interests’. This too is untrue.

I urge you to either produce the evidence for your allegations, or to fully and publicly retract them. This strategy would not merely be the only decent and professional way of dealing with the problem, it also might prevent damage to your reputation, and avoid libel action against you.

Sincerely

Edzard Ernst

Cranio-sacral therapy is firstly implausible, and secondly it lacks evidence of effectiveness (see for instance here, here, here and here). Yet, some researchers are nevertheless not deterred to test it in clinical trials. While this fact alone might be seen as embarrassing, the study below is a particular and personal embarrassment to me, in fact, I am shocked by it and write these lines with considerable regret.

Why? Bear with me, I will explain later.

The purpose of this trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field in temporomandibular disorders. Forty female subjects with temporomandibular disorders lasting at least three months were included. At enrollment, subjects were randomly assigned into two groups: (1) osteopathic manipulative treatment group (n=20) and (2) osteopathy in the cranial field [craniosacral therapy for you and me] group (n=20). Examinations were performed at baseline (E0) and at the end of the last treatment (E1), and consisted of subjective pain intensity with the Visual Analog Scale, Helkimo Index and SF-36 Health Survey. Subjects had five treatments, once a week. 36 subjects completed the study.

Patients in both groups showed significant reduction in Visual Analog Scale score (osteopathic manipulative treatment group: p = 0.001; osteopathy in the cranial field group: p< 0.001), Helkimo Index (osteopathic manipulative treatment group: p = 0.02; osteopathy in the cranial field group: p = 0.003) and a significant improvement in the SF-36 Health Survey – subscale “Bodily Pain” (osteopathic manipulative treatment group: p = 0.04; osteopathy in the cranial field group: p = 0.007) after five treatments (E1). All subjects (n = 36) also showed significant improvements in the above named parameters after five treatments (E1): Visual Analog Scale score (p< 0.001), Helkimo Index (p< 0.001), SF-36 Health Survey – subscale “Bodily Pain” (p = 0.001). The differences between the two groups were not statistically significant for any of the three endpoints.

The authors concluded that both therapeutic modalities had similar clinical results. The findings of this pilot trial support the use of osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field as an effective treatment modality in patients with temporomandibular disorders. The positive results in both treatment groups should encourage further research on osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field and support the importance of an interdisciplinary collaboration in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Implications for rehabilitation Temporomandibular disorders are the second most prevalent musculoskeletal condition with a negative impact on physical and psychological factors. There are a variety of options to treat temporomandibular disorders. This pilot study demonstrates the reduction of pain, the improvement of temporomandibular joint dysfunction and the positive impact on quality of life after osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field. Our findings support the use of osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field and should encourage further research on osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Rehabilitation experts should consider osteopathic manipulative treatment and osteopathy in the cranial field as a beneficial treatment option for temporomandibular disorders.

This study has so many flaws that I don’t know where to begin. Here are some of the more obvious ones:

- There is, as already mentioned, no rationale for this study. I can see no reason why craniosacral therapy should work for the condition. Without such a rationale, the study should never even have been conceived.

- Technically, this RCTs an equivalence study comparing one therapy against another. As such it needs to be much larger to generate a meaningful result and it also would require a different statistical approach.

- The authors mislabelled their trial a ‘pilot study’. However, a pilot study “is a preliminary small-scale study that researchers conduct in order to help them decide how best to conduct a large-scale research project. Using a pilot study, a researcher can identify or refine a research question, figure out what methods are best for pursuing it, and estimate how much time and resources will be necessary to complete the larger version, among other things.” It is not normally a study suited for evaluating the effectiveness of a therapy.

- Any trial that compares one therapy of unknown effectiveness to another of unknown effectiveness is a complete and utter nonsense. Equivalent studies can only ever make sense, if one of the two treatments is of proven effectiveness – think of it as a mathematical equation: one equation with two unknowns is unsolvable.

- Controlled studies such as RCTs are for comparing the outcomes of two or more groups, and only between-group differences are meaningful results of such trials.

- The ‘positive results’ which the authors mention in their conclusions are meaningless because they are based on such within-group changes and nobody can know what caused them: the natural history of the condition, regression towards the mean, placebo-effects, or other non-specific effects – take your pick.

- The conclusions are a bonanza of nonsensical platitudes and misleading claims which do not follow from the data.

As regular readers of this blog will doubtlessly have noticed, I have seen plenty of similarly flawed pseudo-research before – so, why does this paper upset me so much? The reason is personal, I am afraid: even though I do not know any of the authors in person, I know their institution more than well. The study comes from the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Medical University of Vienna, Austria. I was head of this department before I left in 1993 to take up the Exeter post. And I had hoped that, even after 25 years, a bit of the spirit, attitude, knowhow, critical thinking and scientific rigor – all of which I tried so hard to implant in my Viennese department at the time – would have survived.

Perhaps I was wrong.