meta-analysis

This review evaluated the magnitude of the placebo response of sham acupuncture in trials of acupuncture for nonspecific LBP, and assessed whether different types of sham acupuncture are associated with different responses. Four databases including PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Library were searched through April 15, 2023, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included if they randomized patients with LBP to receive acupuncture or sham acupuncture intervention. The main outcomes included the placebo response in pain intensity, back-specific function and quality of life. Placebo response was defined as the change in these outcome measures from baseline to the end of treatment. Random-effects models were used to synthesize the results, standardized mean differences (SMDs, Hedges’g) were applied to estimate the effect size.

A total of 18 RCTs with 3,321 patients were included. Sham acupuncture showed a noteworthy pooled placebo response in pain intensity in patients with LBP [SMD −1.43, 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.95 to −0.91, I2=89%]. A significant placebo response was also shown in back-specific functional status (SMD −0.49, 95% CI −0.70 to −0.29, I2=73%), but not in quality of life (SMD 0.34, 95% CI −0.20 to 0.88, I2=84%). Trials in which the sham acupuncture penetrated the skin or performed with regular needles had a significantly higher placebo response in pain intensity reduction, but other factors such as the location of sham acupuncture did not have a significant impact on the placebo response.

The authors concluded that sham acupuncture is associated with a large placebo response in pain intensity among patients with LBP. Researchers should also be aware that the types of sham acupuncture applied may potentially impact the evaluation of the efficacy of acupuncture. Nonetheless, considering the nature of placebo response, the effect of other contextual factors cannot be ruled out in this study.

As the authors stated in their conclusion: the effect of other contextual factors cannot be ruled out. I would go much further and say that the outcomes noted here are mostly due to effects other than placebo. Obvious candidates are:

- regression towards the mean;

- natural history of the condition;

- success of patient blinding;

- social desirability.

To define the placebo effect in acupuncture trials as the change in the outcome measures from baseline to the end of treatment – as the authors of the review do – is not just naive, it is plainly wrong. I would not be surprised, if different sham acupuncture treatments have different effects. To me this would be an expected, plausible finding. But such differences just cannot be estimated in the way the authors suggest. For that, we would need an RCT in which patients are randomized to be treated in the same setting with a range of different types of sham acupuncture. The results of such a study might be revealing but I doubt that many ethics committees would be happy to grant their approval for it.

In the absence of such data, the best we can do is to design trials such that the verum is tested against a credible placebo which, for patients, is indistinguishable from the verum, while demonstrating that blinding is successful.

Manual therapy is considered a safe and less painful method and has been increasingly used to alleviate chronic neck pain. However, there is controversy about the effectiveness of manipulation therapy on chronic neck pain. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aimed to determine the effectiveness of manipulative therapy for chronic neck pain.

A search of the literature was conducted on seven databases (PubMed, Cochrane Center Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, Medline, CNKI, WanFang, and SinoMed) from the establishment of the databases to May 2022. The review included RCTs on chronic neck pain managed with manipulative therapy compared with sham, exercise, and other physical therapies. The retrieved records were independently reviewed by two researchers. Further, the methodological quality was evaluated using the PEDro scale. All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan V.5.3 software. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) assessment was used to evaluate the quality of the study results.

Seventeen RCTs, including 1190 participants, were included in this meta-analysis. Manipulative therapy showed better results regarding pain intensity and neck disability than the control group. Manipulative therapy was shown to relieve pain intensity (SMD = -0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI] = [-1.04 to -0.62]; p < 0.0001) and neck disability (MD = -3.65; 95% CI = [-5.67 to – 1.62]; p = 0.004). However, the studies had high heterogeneity, which could be explained by the type and control interventions. In addition, there were no significant differences in adverse events between the intervention and the control groups.

The authors concluded that manipulative therapy reduces the degree of chronic neck pain and neck disabilities.

Only a few days ago, we discussed another systematic review that drew quite a different conclusion: there was very low certainty evidence supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain.

How can this be?

Systematic reviews are supposed to generate reliable evidence!

How can we explain the contradiction?

There are several differences between the two papers:

- One was published in a SCAM journal and the other one in a mainstream medical journal.

- One was authored by Chinese researchers, the other one by an international team.

- One included 17, the other one 23 RCTs.

- One assessed ‘manual/manipulative therapies’, the other one spinal manipulation/mobilization.

The most profound difference is that the review by the Chinese authors is mostly on Chimese massage [tuina], while the other paper is on chiropractic or osteopathic spinal manipulation/mobilization. A look at the Chinese authors’ affiliation is revealing:

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China.

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

What lesson can we learn from this confusion?

Perhaps that Tuina is effective for neck pain?

No!

What the abstract does not tell us is that the Tuina studies are of such poor quality that the conclusions drawn by the Chinese authors are not justified.

What we do learn – yet again – is that

- Chinese papers need to be taken with a large pintch of salt. In the present case, the searches underpinning the review and the evaluations of the included primary studies were clearly poorly conducted.

- Rubbish journals publish rubbish papers. How could the reviewers and the editors have missed the many flaws of this paper? The answer seems to be that they did not care. SCAM journals tend to publish any nonsense as long as the conclusion is positive.

This systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) estimated the benefits and harms of cervical spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for treating neck pain. The authors searched the MEDLINE, Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE, CINAHL, PEDro, Chiropractic Literature Index bibliographic databases, and grey literature sources, up to June 6, 2022.

RCTs evaluating SMT compared to guideline-recommended and non-recommended interventions, sham SMT, and no intervention for adults with neck pain were eligible. Pre-specified outcomes included pain, range of motion, disability, health-related quality of life.

A total of 28 RCTs could be included. There was very low to low certainty evidence that SMT was more effective than recommended interventions for improving pain at short-term (standardized mean difference [SMD] 0.66; confidence interval [CI] 0.35 to 0.97) and long-term (SMD 0.73; CI 0.31 to 1.16), and for reducing disability at short-term (SMD 0.95; CI 0.48 to 1.42) and long-term (SMD 0.65; CI 0.23 to 1.06). Only transient side effects were found (e.g., muscle soreness).

The authors concluded that there was very low certainty evidence supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain.

Harms cannot be adequately investigated on the basis of RCT data. Firstly, because much larger sample sizes would be required for this purpose. Secondly, RCTs of spinal manipulation very often omit reporting adverse effects (as discussed repeatedly on this bolg). If we extend our searches beyond RCTs, we find many cases of serious harm caused by neck manipulations (also as discussed repeatedly on this bolg). Therefore, the conclusion of this review should be corrected:

Low certainty evidence exists supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain. The evidence of harm is, however, substantial. It follows that the risk/benefit ratio is not positive. Cervical SMT should therefore be discouraged.

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the effectiveness of visceral osteopathy in improving pain intensity, disability and physical function in patients with low-back pain (LBP).

MEDLINE (Pubmed), PEDro, SCOPUS, Cochrane Library and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to February 2022. PICO search strategy was used to identify randomized clinical trials applying visceral techniques in patients with LBP. Eligible studies and data extraction were conducted independently by two reviewers. Quality of the studies was assessed with the Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale, and the risk of bias with Cochrane Collaboration tool. Meta-analyses were conducted using random effects models according to heterogeneity assessed with I2 coefficient. Data on outcomes of interest were extracted by a researcher using RevMan 5.4 software.

Five studies were included in the systematic review involving 268 patients with LBP. The methodological quality of the included ranged from high to low and the risk of bias was high. Visceral osteopathy techniques have shown no improvements in pain intensity (Standardized mean difference (SMD) = -0.53; 95% CI; -1.09, 0.03; I2: 78%), disability (SMD = -0.08; 95% CI; -0.44, 0.27; I2: 0%) and physical function (SMD = -0.26; 95% CI; -0.62, 0.10; I2: 0%) in patients with LBP.

The authors concluded that this systematic review and meta-analysis showed a lack of high-quality studies showing the effectiveness of visceral osteopathy in pain, disability, and physical function in patients with LBP.

Visceral osteopathy (or visceral manipulation) is an expansion of the general principles of osteopathy and involves the manual manipulation by a therapist of internal organs, blood vessels and nerves (the viscera) from outside the body.

Visceral osteopathy was developed by Jean-Piere Barral, a registered Osteopath and Physical Therapist who serves as Director (and faculty) of the Department of Osteopathic Manipulation in Paris, France. He stated that through his clinical work with thousands of patients, he created this modality based on organ-specific fascial mobilization. And through work in a dissection lab, he was able to experiment with visceral manipulation techniques and see the internal effects of the manipulations.[1] According to its proponents, visceral manipulation is based on the specific placement of soft manual forces looking to encourage the normal mobility, tone and motion of the viscera and their connective tissues. These gentle manipulations may potentially improve the functioning of individual organs, the systems the organs function within, and the structural integrity of the entire body.[2] Visceral osteopathy comprises of several different manual techniques firstly for diagnosing a health problem and secondly for treating it.

Several studies have assessed the diagnostic reliability of the techniques involved. The totality of this evidence fails to show that they are sufficiently reliable to be od practical use.[3] Other studies have tested whether the therapeutic techniques used in visceral osteopathy are effective in curing disease or alleviating symptoms. The totality of this evidence fails to show that visceral osteopathy works for any condition.[4]

The treatment itself seems to be safe, yet the risks of visceral osteopathy are nevertheless considerable: if a patient suffers from symptoms related to her inner organs, the therapist is likely to misdiagnose them and subsequently mistreat them. If the symptoms are due to a serious disease, this would amount to medical neglect and could, in extreme cases, cost the patient’s life.

My bottom line: if you see visceral osteopathy being employed anywhere, turn araound and seek proper healthcare whatever your illness might be.

References

[1] https://www.barralinstitute.com/about/jean-pierre-barral.php .

[2] http://www.barralinstitute.co.uk/ .

[3] Guillaud A, Darbois N, Monvoisin R, Pinsault N (2018) Reliability of diagnosis and clinical efficacy of visceral osteopathy: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med 18:65

As we have recently discussed diet and its effects on health, it seems reasonable to ask whether there is a diet that is demonstrably healthy. A recent investigation attempted to answer this question.

This study was aimed at developing a healthy diet score that is associated with health outcomes and is globally applicable. It used data from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study and tried to replicate it in five independent studies on a total of 245 000 people from 80 countries.

A healthy diet score was developed on the basis of the data from 147 642 people from the general population, from 21 countries in the PURE study. The consistency of the associations of the score with events was examined in five large independent studies from 70 countries.

The healthy diet score was developed based on six foods each of which has been associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality [i.e. fruit, vegetables, nuts, legumes, fish, and dairy (mainly whole-fat); range of scores, 0–6]. The main outcome measures were all-cause mortality and major cardiovascular events [cardiovascular disease (CVD)].

During a median follow-up of 9.3 years in PURE, compared with a diet score of ≤1 point, a diet score of ≥5 points was associated with a lower risk of:

- mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.70; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.63–0.77)],

- CVD (HR 0.82; 0.75–0.91),

- myocardial infarction (HR 0.86; 0.75–0.99),

- stroke (HR 0.81; 0.71–0.93).

In three independent studies with vascular patients, similar results were found, with a higher diet score being associated with lower mortality (HR 0.73; 0.66–0.81), CVD (HR 0.79; 0.72–0.87), myocardial infarction (HR 0.85; 0.71–0.99), and a non-statistically significant lower risk of stroke (HR 0.87; 0.73–1.03). Additionally, in two case-control studies, a higher diet score was associated with lower first myocardial infarction [odds ratio (OR) 0.72; 0.65–0.80] and stroke (OR 0.57; 0.50–0.65). A higher diet score was associated with a significantly lower risk of death or CVD in regions with lower than with higher gross national incomes (P for heterogeneity <0.0001). The PURE score showed slightly stronger associations with death or CVD than several other common diet scores (P < 0.001 for each comparison).

The authors concluded that consumption of a diet comprised of higher amounts of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and a moderate amount of fish and whole-fat dairy is associated with a lower risk of CVD and mortality in all world regions, but especially in countries with lower income where consumption of these natural foods is low. Similar associations were found with the inclusion of meat or whole grain consumption in the diet score (in the ranges common in the six studies that we included). Our findings indicate that the risks of deaths and vascular events in adults globally are higher with inadequate intake of protective foods.

The authors rightly stress that their analyses have a number of limitations:

First, diet (as in most large epidemiologic studies) was self-reported and variations in reporting might lead to random errors that could dilute real associations between diet scores and clinical outcomes. Therefore, the beneficial effects of a healthier diet may be larger than estimated.

Second, the researchers did not examine the role of individual types of fruits and vegetables as components in the diet score, since the power to detect associations of the different types of fruits and vegetables vs. CVD or mortality is low (i.e. given that the number of events per type of fruit and vegetable was relatively low). Recent evidence suggests that bioactive compounds and, in particular, polyphenols which are found in certain fruit or vegetables (e.g. berries, spinach, and beans) may be especially protective against CVD.

Third, in observational studies, the possibility of residual confounding from unquantified or imprecise measurement of covariates cannot be ruled out—especially given that the differences in risk of clinical events are modest (∼10%–20% relative differences). Ideally, large randomized trials would be needed to clarify the clinical impact on events of a policy of proposing a dietary pattern in populations.

Fourth, the use of the median intake of each food component as a cut-off in the scoring scheme for each diet may not reflect the full range of consumption or provide a meaningful indicator of consumption associated with the disease. However, the use of quintiles instead of medians within each study or within each region yielded the same results indicating the robustness of our findings.

Fifth, the level of intake to meet the cut-off threshold for each food group in the diet score may differ between countries. However, in sensitivity analyses where region-specific median cut-offs were used to classify participants on each component of the diet score, the results were similar to using the overall cohort median of each food component. Further, with unprocessed red meat and whole grains included or excluded from the diet score in these sensitivity analyses, the results were again similar.

Sixth, misclassification of exposures cannot be ruled out as repeat measures of diet were not available in all studies. However, the ORIGIN study, in which repeat diet assessments at 2 years were conducted, showed similar results based on the first vs. second diet assessments. This indicates that misclassification of dietary intake during follow-up was not undermining the findings.

Seventh, one unique aspect of the study is the focus on only protective foods, i.e. a dietary pattern score that highlights what is missing from the food supply, especially in poorer world regions, but this does not negate the importance of limiting the consumption of harmful foods such as highly processed foods. While the PURE diet score had significantly stronger associations with events than other diet scores, the HRs were only slightly larger for PURE than for most other diet scores. However, the Planetary score was the least predictive of events. The analyses provide empirical evidence that all diet scores (other than the Planetary diet score) are of value to predicting death or CVD globally and in all regions of the world.

So, what should we, according to these findings, be looking for and how much of it should we consume? Here is the table that should answer these questions:

| Fruits and vegetables | 4 to 5 servings daily | 1 medium apple, banana, pear; 1 cup leafy vegs; 1/2 cup other vegs |

| Legumes | 3 to 4 servings weekly | 1/2 cup beans or lentils |

| Nuts | 7 servings weekly | 1 oz., tree nuts or peanuts |

| Fish | 2 to 3 servings weekly | 3 oz. cooked (pack of cards size) |

| Dairy | 14 servings weekly | 1 cup milk or yogurt; 1 ½ oz cheese |

| Whole grainsc | Moderate amounts (e.g. 1 serving daily) can be part of a healthy diet | 1 slice (40 g) bread; ½ medium (40 g) flatbread; ½ cup (75–120 g) cooked rice, barley, buckwheat, semolina, polenta, bulgur, or quinoa |

| Unprocessed meatsc | Moderate amounts (e.g. 1 serving daily) can be part of a healthy diet | 3 oz. cooked red meat or poultry |

There is widespread agreement amongst clinicians that people with non-specific low back pain (NSLBP) comprise a heterogeneous group and that their management should be individually tailored. One treatment known by its tailored design is the McKenzie method (e.g. an individualized program of exercises based on clinical clues observed during assessment) used mostly but not exclusively by physiotherapists.

A recent Cochrane review evaluated the effectiveness of the McKenzie method in people with (sub)acute non-specific low back pain. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) investigating the effectiveness of the McKenzie method in adults with (sub)acute (less than 12 weeks) NSLBP.

Five RCTs were included with a total of 563 participants recruited from primary or tertiary care. Three trials were conducted in the USA, one in Australia, and one in Scotland. Three trials received financial support from non-commercial funders and two did not provide information on funding sources. All trials were at high risk of performance and detection bias. None of the included trials measured adverse events.

McKenzie method versus minimal intervention (educational booklet; McKenzie method as a supplement to other intervention – main comparison) There is low-certainty evidence that the McKenzie method may result in a slight reduction in pain in the short term (MD -7.3, 95% CI -12.0 to -2.56; 2 trials, 377 participants) but not in the intermediate term (MD -5.0, 95% CI -14.3 to 4.3; 1 trial, 180 participants). There is low-certainty evidence that the McKenzie method may not reduce disability in the short term (MD -2.5, 95% CI -7.5 to 2.0; 2 trials, 328 participants) nor in the intermediate term (MD -0.9, 95% CI -7.3 to 5.6; 1 trial, 180 participants).

McKenzie method versus manual therapy There is low-certainty evidence that the McKenzie method may not reduce pain in the short term (MD -8.7, 95% CI -27.4 to 10.0; 3 trials, 298 participants) and may result in a slight increase in pain in the intermediate term (MD 7.0, 95% CI 0.7 to 13.3; 1 trial, 235 participants). There is low-certainty evidence that the McKenzie method may not reduce disability in the short term (MD -5.0, 95% CI -15.0 to 5.0; 3 trials, 298 participants) nor in the intermediate term (MD 4.3, 95% CI -0.7 to 9.3; 1 trial, 235 participants).

McKenzie method versus other interventions (massage and advice) There is very low-certainty evidence that the McKenzie method may not reduce disability in the short term (MD 4.0, 95% CI -15.4 to 23.4; 1 trial, 30 participants) nor in the intermediate term (MD 10.0, 95% CI -8.9 to 28.9; 1 trial, 30 participants).

The authors concluded that, based on low- to very low-certainty evidence, the treatment effects for pain and disability found in our review were not clinically important. Thus, we can conclude that the McKenzie method is not an effective treatment for (sub)acute NSLBP.

The hallmark of the McKenzie method for back pain involves the identification and classification of nonspecific spinal pain into homogenous subgroups. These subgroups are based on the similar responses of a patient’s symptoms when subjected to mechanical forces. The subgroups include postural syndrome, dysfunction syndrome, derangement syndrome, or “other,” with treatment plans directed to each subgroup. The McKenzie method emphasizes the centralization phenomenon in the assessment and treatment of spinal pain, in which pain originating from the spine refers distally, and through targeted repetitive movements the pain migrates back toward the spine. The clinician will then use the information obtained from this assessment to prescribe specific exercises and advise on which postures to adopt or avoid. Through an individualized treatment program, the patient will perform specific exercises at home approximately ten times per day, as opposed to 1 or 2 physical therapy visits per week. According to the McKenzie method, if there is no restoration of normal function, tissue healing will not occur, and the problem will persist.

Classification:

The postural syndrome is pain caused by mechanical deformation of soft tissue or vasculature arising from prolonged postural stresses. These may affect the joint surfaces, muscles, or tendons, and can occur in sitting, standing, or lying. Pain may be reproducible when such individuals maintain positions or postures for sustained periods. Repeated movements should not affect symptoms, and relief of pain typically occurs immediately following the correction of abnormal posture.

The dysfunction syndrome is pain caused by the mechanical deformation of structurally impaired soft tissue; this may be due to traumatic, inflammatory, or degenerative processes, causing tissue contraction, scarring, adhesion, or adaptive shortening. The hallmark is a loss of movement and pain at the end range of motion. Dysfunction has subsyndromes based upon the end-range direction that elicits this pain: flexion, extension, side-glide, multidirectional, adherent nerve root, and nerve root entrapment subsyndromes. Successful treatment focuses on patient education and mobilization exercises that focus on the direction of the dysfunction/direction of pain. The goal is on tissue remodeling which can be a prolonged process.

The derangement syndrome is the most commonly encountered pain syndrome, reported in one study to have a prevalence as high as 78% of patients classified by the McKenzie method. It is caused by an internal dislocation of articular tissue, causing a disturbance in the normal position of affected joint surfaces, deforming the capsule, and periarticular supportive ligaments. This derangement will both generate pain and obstruct movement in the direction of the displacement. There are seven different subsyndromes which are classified by the location of pain and the presence, or absence, of deformities. Pain is typically elicited by provocative assessment movements, such as flexion or extension of the spine. The centralization and peripheralization of symptoms can only occur in the derangement syndrome. Thus the treatment for derangement syndrome focuses on repeated movement in a single direction that causes a gradual reduction in pain. Studies have shown approximately anywhere between 58% to 91% prevalence of centralization of lower back pain. Studies have also shown that between 67% to 85% of centralizers displayed the directional preference for a spinal extension. This preference may partially explain why the McKenzie method has become synonymous with spinal extension exercises. However, care must be taken to accurately diagnose the direction of pain, as one randomized controlled study has shown that giving the ‘wrong’ direction of exercises can actually lead to poorer outcomes.

Other or Nonmechanical syndrome refers to any symptom that does not fit in with the other mechanical syndromes, but exhibits signs and symptoms of other known pathology; Some of these examples include spinal stenosis, sacroiliac disorders, hip disorders, zygapophyseal disorders, post-surgical complications, low back pain secondary to pregnancy, spondylolysis, and spondylolisthesis.

CONCLUSION:

“Internationally researched” and found to be ineffective!

I have seen some daft meta-analyses in my time – this one, however, takes the biscuit. Here is its unaltered abstract:

Although mindfulness-based mind-body therapy (MBMBT) is an effective non-surgical treatment for patients with non-specific low back pain (NLBP), the best MBMBT mode of treatment for NLBP patients has not been identified. Therefore, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was conducted to compare the effects of different MBMBTs in the treatment of NLBP patients.

Methods: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Web of Science databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) applying MBMBT for the treatment of NLBP patients, with all of the searches ranging from the time of database creation to January 2023. After 2 researchers independently screened the literature, extracted information, and evaluated the risks of biases in the included studies, the data were analyzed by using Stata 16.0 software.

Results: A total of 46 RCTs were included, including 3,886 NLBP patients and 9 MBMBT (Yoga, Ayurvedic Massage, Pilates, Craniosacral Therapy, Meditation, Meditation + Yoga, Qigong, Tai Chi, and Dance). The results of the NMA showed that Craniosacral Therapy [surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA): 99.2 and 99.5%] ranked the highest in terms of improving pain and disability, followed by Other Manipulations (SUCRA: 80.6 and 90.8%) and Pilates (SUCRA: 54.5 and 71.2%). In terms of improving physical health, Craniosacral Therapy (SUCRA: 100%) ranked the highest, followed by Pilates (SUCRA: 72.3%) and Meditation (SUCRA: 55.9%). In terms of improving mental health, Craniosacral Therapy (SUCRA: 100%) ranked the highest, followed by Meditation (SUCRA: 70.7%) and Pilates (SUCRA: 63.2%). However, in terms of improving pain, physical health, and mental health, Usual Care (SUCRA: 7.0, 14.2, and 11.8%, respectively) ranked lowest. Moreover, in terms of improving disability, Dance (SUCRA: 11.3%) ranked lowest.

Conclusion: This NMA shows that Craniosacral Therapy may be the most effective MBMBT in treating NLBP patients and deserves to be promoted for clinical use.

___________________________

This meta-analysis has too many serious flaws to mention. Let me therefore just focus on the main two:

- Craniosacral Therapy is not an MBMBT.

- Craniosacral Therapy is not effective for NLBP. The false positive result was generated on the basis of 4 studies. All of them have serious methodological problems that prevent an overall positive conclusion about the effectiveness of this treatment. In case you don’t believe me, here are the 4 abstracts:

1) Background and objectives: The study aimed to compare the effectiveness of craniosacral therapy (CST), muscle energy technique (MET), and sensorimotor training (SMT) on pain, disability, depression, and quality of life of patients with non-specific chronic low back pain (NCLBP).

Methodology: In this randomized clinical trial study 45 patients with NCLBP were randomly divided in three groups including CST, SMT, and MET. All groups received 10 sessions CST, SMT, and MET training in 5 weeks. Visual analogue scale (VAS), Oswestry functional disability questionnaire (ODQ), Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II), and 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) were used to evaluate the pain, disability, depression, and quality of life, respectively, in three times, before treatment, after the last session of treatment, and after 2 months follow up.

Results: The Results showed that VAS, ODI, BDI, and SF-36 changes were significant in the groups SMT, CST and MET (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p < 0.001). The VAS, ODI, BDI, and SF-36 changes in post-treatment and follow-up times in the CST group were significantly different in comparison to SMT group, and the changes in VAS, ODI, BDI, and SF-36 at after treatment and follow-up times in the MET group compared with the CST group had a significant difference (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Craniosacral therapy, muscle energy technique, and sensorimotor training were all effective in improvement of pain, depression, functional disability, and quality of life of patients with non-specific chronic low back pain. Craniosacral therapy is more effective than muscle energy technique, and sensorimotor training in post-treatment and follow up. The effect of craniosacral therapy was continuous after two months follow up.

2) Background: Craniosacral therapy (CST) and sensorimotor training (SMT) are two recommended interventions for nonspecific chronic low back pain (NCLBP). This study compares the effects of CST and SMT on pain, functional disability, depression and quality of life in patients with NCLBP.

Methodology: A total of 31 patients with NCLBP were randomly assigned to the CST group (n=16) and SMT (n=15). The study patients received 10 sessions of interventions during 5 weeks. Visual analogue scale (VAS), Oswestry disability index (ODI), Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II), and Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaires were used at baseline (before the treatment), after the treatment, and 2 months after the last intervention session. Results were compared and analyzed statistically.

Results: Both groups showed significant improvement from baseline to after treatment (p < 0.05). In the CST group, this improvement continued during the follow-up period in all outcomes (p < 0.05), except role emotional domain of SF-36. In the SMT group, VAS, ODI and BDI-II increased during follow-up. Also, all domains of SF-36 decreased over this period. Results of group analysis indicate a significant difference between groups at the end of treatment phase (p < 0.05), except social functioning.

Conclusions: Results of our research confirm that 10 sessions of craniosacral therapy (CST) or sensorimotor training (SMT) can significantly control pain, disability, depression, and quality of life in patients with NCLBP; but the efficacy of CST is significantly better than SMT.

3) Background: Non-specific low back pain is an increasingly common musculoskeletal ailment. The aim of this study was to examine the utility of craniosacral therapy techniques in the treatment of patients with lumbosacral spine overload and to compare its effectiveness to that of trigger point therapy, which is a recognised therapeutic approach.

Material and methods: The study enrolled 55 randomly selected patients (aged 24-47 years) with low back pain due to overload. Other causes of this condition in the patients were ruled out. The participants were again randomly assigned to two groups: patients treated with craniosacral therapy (G-CST) and patients treated with trigger point therapy (G-TPT). Multiple aspects of the effectiveness of both therapies were evaluated with the use of: an analogue scale for pain (VAS) and a modified Laitinen questionnaire, the Schober test and surface electromyography of the multifidus muscle. The statistical analysis of the outcomes was based on the basic statistics, the Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon’s signed rank test. The statistical significance level was set at p≤0.05.

Results: Both groups demonstrated a significant reduction of pain measured with the VAS scale and the Laitinen questionnaire. Moreover, the resting bioelectric activity of the multifidus muscle decreased significantly in the G-CST group. The groups did not differ significantly with regard to the study parameters.

Conclusions: 1. Craniosacral therapy and trigger point therapy may effectively reduce the intensity and frequency of pain in patients with non-specific low back pain. 2. Craniosacral therapy, unlike trigger point therapy, reduces the resting tension of the multifidus muscle in patients with non-specific lumbosacral pain. The mechanism of these changes requires further research. 3. Craniosacral therapy and trigger point therapy may be clinically effective in the treatment of patients with non-specific lumbosacral spine pain. 4. The present findings represent a basis for conducting further and prospective studies of larger and randomized samples.

4) Background: Non-specific low back pain is an increasingly common musculoskeletal ailment. The aim of this study was to examine the utility of craniosacral therapy techniques in the treatment of patients with lumbosacral spine overload and to compare its effectiveness to that of trigger point therapy, which is a recognised therapeutic approach.

Material and methods: The study enrolled 55 randomly selected patients (aged 24-47 years) with low back pain due to overload. Other causes of this condition in the patients were ruled out. The participants were again randomly assigned to two groups: patients treated with craniosacral therapy (G-CST) and patients treated with trigger point therapy (G-TPT). Multiple aspects of the effectiveness of both therapies were evaluated with the use of: an analogue scale for pain (VAS) and a modified Laitinen questionnaire, the Schober test and surface electromyography of the multifidus muscle. The statistical analysis of the outcomes was based on the basic statistics, the Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon’s signed rank test. The statistical significance level was set at p≤0.05.

Results: Both groups demonstrated a significant reduction of pain measured with the VAS scale and the Laitinen questionnaire. Moreover, the resting bioelectric activity of the multifidus muscle decreased significantly in the G-CST group. The groups did not differ significantly with regard to the study parameters.

Conclusions: 1. Craniosacral therapy and trigger point therapy may effectively reduce the intensity and frequency of pain in patients with non-specific low back pain. 2. Craniosacral therapy, unlike trigger point therapy, reduces the resting tension of the multifidus muscle in patients with non-specific lumbosacral pain. The mechanism of these changes requires further research. 3. Craniosacral therapy and trigger point therapy may be clinically effective in the treatment of patients with non-specific lumbosacral spine pain. 4. The present findings represent a basis for conducting further and prospective studies of larger and randomized samples.

_______________________________

I REST MY CASE

Lumbosacral Radicular Syndrome (LSRS) is a condition characterized by pain radiating in one or more dermatomes (Radicular Pain) and/or the presence of neurological impairments (Radiculopathy). So far, different reviews have investigated the effect of HVLA (high-velocity low-amplitude) spinal manipulations in LSRS. However, these studies included ‘mixed’ population samples (LBP patients with or without LSRS) and treatments other than HVLA spinal manipulations (e.g., mobilisation, soft tissue treatment, etc.). Hence, the efficacy of HVLAT in LSRS is yet to be fully understood.

This review investigated the effect and safety of HVLATs on pain, levels of disability, and health-related quality of life in LSRS, as well as any possible adverse events.

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) published in English in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, PEDro, and Web of Science were identified. RCTs on an adult population (18-65 years) with LSRS that compared HVLATs with other non-surgical treatments, sham spinal manipulation, or no intervention were considered. Two authors selected the studies, extracted the data, and assessed the methodological quality through the ‘Risk of Bias (RoB) Tool 2.0’ and the certainty of the evidence through the ‘GRADE tool’. A meta-analysis was performed to quantify the effect of HVLA on pain levels.

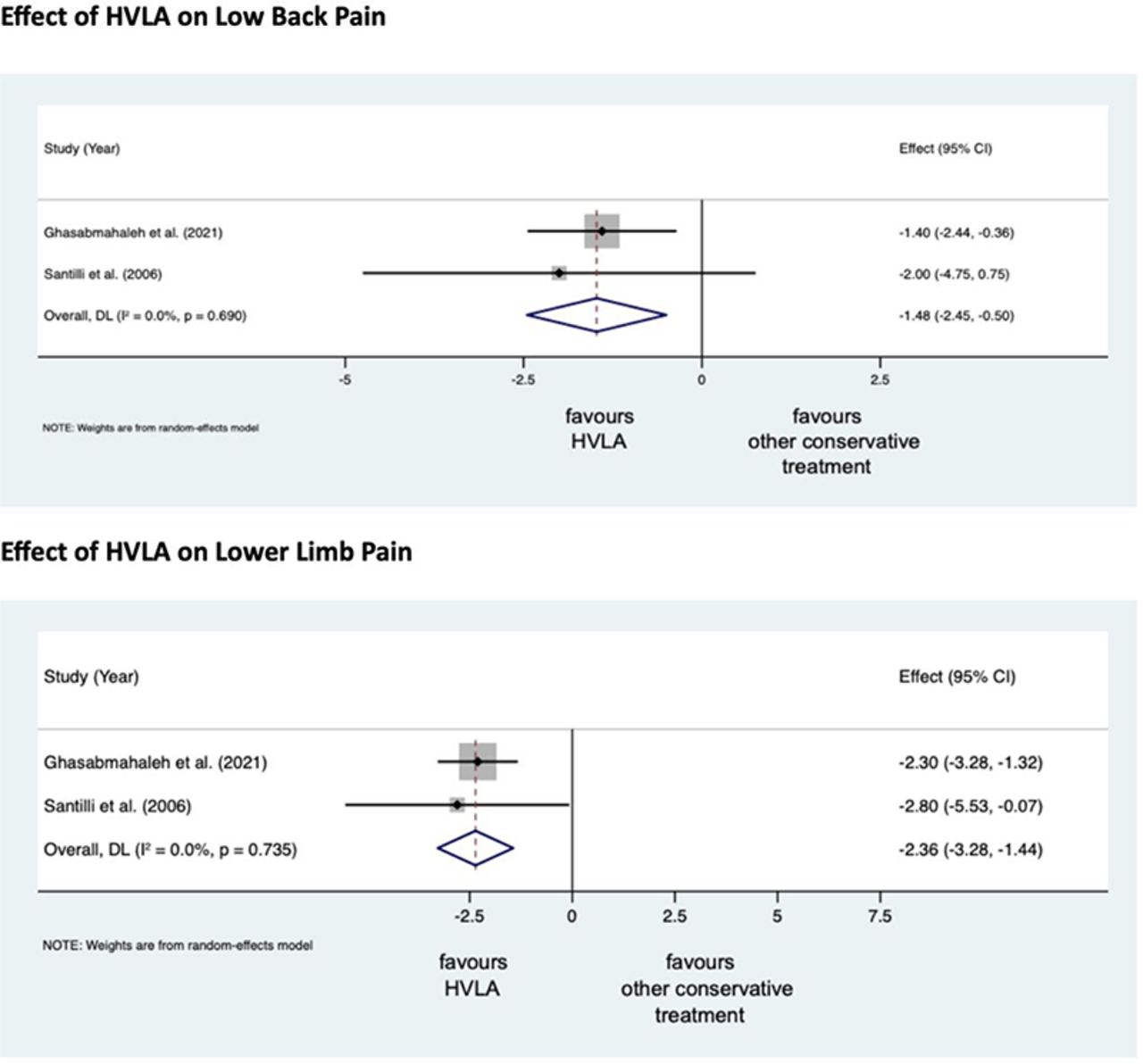

A total of 308 records were retrieved from the search strings. Only two studies met the inclusion criteria. Both studies were at high RoB. Two meta-analyses were performed for low back and leg pain levels. HVLA seemed to reduce the levels of low back (MD = -1.48; 95% CI = -2.45, -0.50) and lower limb (MD = -2.36; 95% CI = -3.28, -1.44) pain compared to other conservative treatments, at three months after treatment. However, high heterogeneity was found (I² = 0.0%, p = 0.735). Besides, their certainty of the evidence was ‘very low’. No adverse events were reported.

The authors stated that they cannot conclude whether HVLA spinal manipulations can be helpful for the treatment of LSRS or not. Future high-quality RCTs are needed to establish the actual effect of HVLA manipulation in this disease with adequate sample size and LSRS definition.

Chiropractors earn their living by applying HVLA thrusts to patients suffering from LSRS. One would therefore have assumed that the question of efficacy has been extensively researched and conclusively answered. It seems that one would have assumed wrongly!

Now that this is (yet again) in the open, I wonder whether chiropractors will, in the future, tell their patients while obtaining informed consent: “I plan to give you a treatment for which sound evidence is not available; it can also cause harm; and, of course, it will cost you – I hope you don’t mind.”

On this blog, we have some people who continue to promote conspiracy theories about Covid and Covid vaccinations. It is, therefore, time, I feel, to present them with some solid evidence on the subject (even though it means departing from our usual focus on SCAM).

This Cochrane review assessed the efficacy and safety of COVID‐19 vaccines (as a full primary vaccination series or a booster dose) against SARS‐CoV‐2. An impressive team of investigators searched the Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register and the COVID‐19 L·OVE platform (last search date 5 November 2021). They also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, regulatory agency websites, and Retraction Watch. They included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing COVID‐19 vaccines to placebo, no vaccine, other active vaccines, or other vaccine schedules.

A total of 41 RCTs could be included and analyzed assessing 12 different vaccines, including homologous and heterologous vaccine schedules and the effect of booster doses. Thirty‐two RCTs were multicentre and five were multinational. The sample sizes of RCTs were 60 to 44,325 participants. Participants were aged: 18 years or older in 36 RCTs; 12 years or older in one RCT; 12 to 17 years in two RCTs; and three to 17 years in two RCTs. Twenty‐nine RCTs provided results for individuals aged over 60 years, and three RCTs included immunocompromised patients. No trials included pregnant women. Sixteen RCTs had two‐month follow-ups or less, 20 RCTs had two to six months, and five RCTs had greater than six to 12 months or less. Eighteen reports were based on preplanned interim analyses. The overall risk of bias was low for all outcomes in eight RCTs, while 33 had concerns for at least one outcome. 343 registered RCTs with results not yet available were identified.The evidence for mortality was generally sparse and of low or very low certainty for all WHO‐approved vaccines, except AD26.COV2.S (Janssen), which probably reduces the risk of all‐cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.67; 1 RCT, 43,783 participants; high‐certainty evidence).High‐certainty evidence was found that BNT162b2 (BioNtech/Fosun Pharma/Pfizer), mRNA‐1273 (ModernaTx), ChAdOx1 (Oxford/AstraZeneca), Ad26.COV2.S, BBIBP‐CorV (Sinopharm‐Beijing), and BBV152 (Bharat Biotect) reduce the incidence of symptomatic COVID‐19 compared to placebo (vaccine efficacy (VE): BNT162b2: 97.84%, 95% CI 44.25% to 99.92%; 2 RCTs, 44,077 participants; mRNA‐1273: 93.20%, 95% CI 91.06% to 94.83%; 2 RCTs, 31,632 participants; ChAdOx1: 70.23%, 95% CI 62.10% to 76.62%; 2 RCTs, 43,390 participants; Ad26.COV2.S: 66.90%, 95% CI 59.10% to 73.40%; 1 RCT, 39,058 participants; BBIBP‐CorV: 78.10%, 95% CI 64.80% to 86.30%; 1 RCT, 25,463 participants; BBV152: 77.80%, 95% CI 65.20% to 86.40%; 1 RCT, 16,973 participants).Moderate‐certainty evidence was found that NVX‐CoV2373 (Novavax) probably reduces the incidence of symptomatic COVID‐19 compared to placebo (VE 82.91%, 95% CI 50.49% to 94.10%; 3 RCTs, 42,175 participants).There is low‐certainty evidence for CoronaVac (Sinovac) for this outcome (VE 69.81%, 95% CI 12.27% to 89.61%; 2 RCTs, 19,852 participants).High‐certainty evidence was found that BNT162b2, mRNA‐1273, Ad26.COV2.S, and BBV152 result in a large reduction in the incidence of severe or critical disease due to COVID‐19 compared to placebo (VE: BNT162b2: 95.70%, 95% CI 73.90% to 99.90%; 1 RCT, 46,077 participants; mRNA‐1273: 98.20%, 95% CI 92.80% to 99.60%; 1 RCT, 28,451 participants; AD26.COV2.S: 76.30%, 95% CI 57.90% to 87.50%; 1 RCT, 39,058 participants; BBV152: 93.40%, 95% CI 57.10% to 99.80%; 1 RCT, 16,976 participants).

Moderate‐certainty evidence was found that NVX‐CoV2373 probably reduces the incidence of severe or critical COVID‐19 (VE 100.00%, 95% CI 86.99% to 100.00%; 1 RCT, 25,452 participants).

Two trials reported high efficacy of CoronaVac for severe or critical disease with wide CIs, but these results could not be pooled.

mRNA‐1273, ChAdOx1 (Oxford‐AstraZeneca)/SII‐ChAdOx1 (Serum Institute of India), Ad26.COV2.S, and BBV152 probably result in little or no difference in serious adverse events (SAEs) compared to placebo (RR: mRNA‐1273: 0.92, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.08; 2 RCTs, 34,072 participants; ChAdOx1/SII‐ChAdOx1: 0.88, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.07; 7 RCTs, 58,182 participants; Ad26.COV2.S: 0.92, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.22; 1 RCT, 43,783 participants); BBV152: 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.97; 1 RCT, 25,928 participants). In each of these, the likely absolute difference in effects was fewer than 5/1000 participants.

Evidence for SAEs is uncertain for BNT162b2, CoronaVac, BBIBP‐CorV, and NVX‐CoV2373 compared to placebo (RR: BNT162b2: 1.30, 95% CI 0.55 to 3.07; 2 RCTs, 46,107 participants; CoronaVac: 0.97, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.51; 4 RCTs, 23,139 participants; BBIBP‐CorV: 0.76, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.06; 1 RCT, 26,924 participants; NVX‐CoV2373: 0.92, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.14; 4 RCTs, 38,802 participants).

The authors’ conclusions were as follows: Compared to placebo, most vaccines reduce, or likely reduce, the proportion of participants with confirmed symptomatic COVID‐19, and for some, there is high‐certainty evidence that they reduce severe or critical disease. There is probably little or no difference between most vaccines and placebo for serious adverse events. Over 300 registered RCTs are evaluating the efficacy of COVID‐19 vaccines, and this review is updated regularly on the COVID‐NMA platform (covid-nma.com).

_____________________

As some conspiratorial loons will undoubtedly claim that this review is deeply biased; it might be relevant to add the conflicts of interest of its authors:

- Carolina Graña: none known.

- Lina Ghosn: none known.

- Theodoros Evrenoglou: none known.

- Alexander Jarde: none known.

- Silvia Minozzi: no relevant interests; Joint Co‐ordinating Editor and Method editor of the Drugs and Alcohol Group.

- Hanna Bergman: Cochrane Response – consultant; WHO – grant/contract (Cochrane Response was commissioned by the WHO to perform review tasks that contribute to this publication).

- Brian Buckley: none known.

- Katrin Probyn: Cochrane Response – consultant; WHO – consultant (Cochrane Response was commissioned to perform review tasks that contribute to this publication).

- Gemma Villanueva: Cochrane Response – employment (Cochrane Response has been commissioned by WHO to perform parts of this systematic review).

- Nicholas Henschke: Cochrane Response – consultant; WHO – consultant (Cochrane Response was commissioned by the WHO to perform review tasks that contributed to this publication).

- Hillary Bonnet: none known.

- Rouba Assi: none known.

- Sonia Menon: P95 – consultant.

- Melanie Marti: no relevant interests; Medical Officer at WHO.

- Declan Devane: Health Research Board (HRB) – grant/contract; registered nurse and registered midwife but no longer in clinical practice; Editor, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

- Patrick Mallon: AstraZeneca – Advisory Board; spoken of vaccine effectiveness to media (print, online, and live); works as a consultant in a hospital that provides vaccinations; employed by St Vincent’s University Hospital.

- Jean‐Daniel Lelievre: no relevant interests; published numerous interviews in the national press on the subject of COVID vaccination; Head of the Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Immunology CHU Henri Mondor APHP, Créteil; WHO (IVRI‐AC): expert Vaccelarate (European project on COVID19 Vaccine): head of WP; involved with COVICOMPARE P et M Studies (APHP, INSERM) (public fundings).

- Lisa Askie: no relevant interests; Co‐convenor, Cochrane Prospective Meta‐analysis Methods Group.

- Tamara Kredo: no relevant interests; Medical Officer in an Infectious Diseases Clinic at Tygerberg Hospital, Stellenbosch University.

- Gabriel Ferrand: none known.

- Mauricia Davidson: none known.

- Carolina Riveros: no relevant interests; works as an epidemiologist.

- David Tovey: no relevant interests; Emeritus Editor in Chief, Feedback Editors for 2 Cochrane review groups.

- Joerg J Meerpohl: no relevant interests; member of the German Standing Vaccination Committee (STIKO).

- Giacomo Grasselli: Pfizer – speaking engagement.

- Gabriel Rada: none known.

- Asbjørn Hróbjartsson: no relevant interests; Cochrane Methodology Review Group Editor.

- Philippe Ravaud: no relevant interests; involved with Mariette CORIMUNO‐19 Collaborative 2021, the Ministry of Health, Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique, Foundation for Medical Research, and AP‐HP Foundation.

- Anna Chaimani: none known.

- Isabelle Boutron: no relevant interests; member of Cochrane Editorial Board.

___________________________

And as some might say this analysis is not new, here are two further papers just out:

Objectives To determine the association between covid-19 vaccination types and doses with adverse outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection during the periods of delta (B.1.617.2) and omicron (B.1.1.529) variant predominance.

Design Retrospective cohort.

Setting US Veterans Affairs healthcare system.

Participants Adults (≥18 years) who are affiliated to Veterans Affairs with a first documented SARS-CoV-2 infection during the periods of delta (1 July-30 November 2021) or omicron (1 January-30 June 2022) variant predominance. The combined cohorts had a mean age of 59.4 (standard deviation 16.3) and 87% were male.

Interventions Covid-19 vaccination with mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna)) and adenovirus vector vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson)).

Main outcome measures Stay in hospital, intensive care unit admission, use of ventilation, and mortality measured 30 days after a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2.

Results In the delta period, 95 336 patients had infections with 47.6% having at least one vaccine dose, compared with 184 653 patients in the omicron period, with 72.6% vaccinated. After adjustment for patient demographic and clinical characteristics, in the delta period, two doses of the mRNA vaccines were associated with lower odds of hospital admission (adjusted odds ratio 0.41 (95% confidence interval 0.39 to 0.43)), intensive care unit admission (0.33 (0.31 to 0.36)), ventilation (0.27 (0.24 to 0.30)), and death (0.21 (0.19 to 0.23)), compared with no vaccination. In the omicron period, receipt of two mRNA doses were associated with lower odds of hospital admission (0.60 (0.57 to 0.63)), intensive care unit admission (0.57 (0.53 to 0.62)), ventilation (0.59 (0.51 to 0.67)), and death (0.43 (0.39 to 0.48)). Additionally, a third mRNA dose was associated with lower odds of all outcomes compared with two doses: hospital admission (0.65 (0.63 to 0.69)), intensive care unit admission (0.65 (0.59 to 0.70)), ventilation (0.70 (0.61 to 0.80)), and death (0.51 (0.46 to 0.57)). The Ad26.COV2.S vaccination was associated with better outcomes relative to no vaccination, but higher odds of hospital stay and intensive care unit admission than with two mRNA doses. BNT162b2 was generally associated with worse outcomes than mRNA-1273 (adjusted odds ratios between 0.97 and 1.42).

Conclusions In veterans with recent healthcare use and high occurrence of multimorbidity, vaccination was robustly associated with lower odds of 30 day morbidity and mortality compared with no vaccination among patients infected with covid-19. The vaccination type and number of doses had a significant association with outcomes.

SECOND EXAMPLE Long COVID, or complications arising from COVID-19 weeks after infection, has become a central concern for public health experts. The United States National Institutes of Health founded the RECOVER initiative to better understand long COVID. We used electronic health records available through the National COVID Cohort Collaborative to characterize the association between SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and long COVID diagnosis. Among patients with a COVID-19 infection between August 1, 2021 and January 31, 2022, we defined two cohorts using distinct definitions of long COVID—a clinical diagnosis (n = 47,404) or a previously described computational phenotype (n = 198,514)—to compare unvaccinated individuals to those with a complete vaccine series prior to infection. Evidence of long COVID was monitored through June or July of 2022, depending on patients’ data availability. We found that vaccination was consistently associated with lower odds and rates of long COVID clinical diagnosis and high-confidence computationally derived diagnosis after adjusting for sex, demographics, and medical history.

_______________________________________

There are, of course, many more articles on the subject for anyone keen to see the evidence. Sadly, I have little hope that the COVID loons will be convinced by any of them. Yet, I thought I should give it nevertheless a try.

A team of French researchers assessed whether a conflict of interest (COI) might be associated with the direction of the results of meta-analyses of homoeopathy trials. Their analysis (published as a ‘letter to the editor) is complex, therefore, I present here only their main finding.

The team conducted a literature search until July 2022 on PubMed and Embase to identify meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials assessing the efficacy of homoeopathy. They then assessed the existence of potential COI, defined by the presence of at least one of the following criteria:

- affiliation of one or more authors to an academic homoeopathy research or care facility, or to the homoeopathy industry;

- research sponsored or funded by the homoeopathy industry;

- COI declared by the authors.

The researchers also evaluated and classified any spin in meta-analyses conclusions into three categories (misleading reporting, misleading interpretation and inappropriate extrapolation). Two reviewers assessed the quality of meta-analyses and the risk of bias based. Publication bias was evaluated by the funnel plot method. For all the studies included in these meta-analyses, the researchers checked whether they reported a statistically significant result in favour of homoeopathy. Further details about the methods are provided on OSF (https://osf.io/nqw7r/) and in the preregistered protocol (CRD42020206242).

Twenty meta-analyses were included in the analysis (list of references available at https://osf.io/nqw7r/).

- Among the 13 meta-analyses with COI, a significantly positive effect of homoeopathy emerged (OR=0.60 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.70)).

- There was no such effect for meta-analyses without COI (OR=0.96 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.23)).

The authors concluded that in the presence of COI, meta-analyses of homoeopathy trials are more likely

to have favourable results. This is consistent with recent research suggesting that systematic reviews with financial COI are associated with more positive outcomes.

Meta-analyses are systematic reviews (critical assessments of the totality of the available evidence) where the data from the included studies are pooled. For a range of reasons, this may not always be possible. Therefore the number of meta-analyses (20) is substantially lower than that of the existing systematic reviews (>50).

Both systematic reviews and meta-analyses are theoretically the most reliable evidence regarding the value of any intervention. I said ‘theoretically’ because, like any human endeavour, they need to be done in an unbiased fashion to produce reliable results. People with a conflict of interest by definition struggle to be free of bias. As we have seen many times, this would include homoeopaths.

This new analysis confirms what many of us have feared. If proponents of homeopathy with an overt conflict of interest conduct a meta-analysis of studies of homeopathy, the results tend to be more positive than when independent researchers do it. The question that emerges from this is the following:

Are the findings of those researchers who have an interest in producing a positive result closer to the truth than the findings of researchers who have no such conflict?

I let you decide.