back pain

Chiropractors often refer their patients for full-length (three- to four-region) radiographs of the spine as part of their clinical assessment, which are frequently completed by radiographers in medical imaging practices. Overuse of spinal radiography by chiropractors has previously been reported and remains a contentious issue.

The purpose of this scoping review was to explore the issues surrounding the utilization of full-length spinal radiography by chiropractors and examine the alignment of this practice with current evidence.

A search of four databases (AMED, EMBASE, MedLine and Scopus) and a hand search of Google was conducted. Articles were screened against an inclusion/exclusion criterion for relevance. Themes and findings were extracted from eligible articles, and evidence was synthesized using a narrative approach.

In total, 25 articles were identified, five major themes were extracted, and subsequent conclusions drawn by authors were charted to identify confluent findings:

- (1) The historical integration of FLS radiography in chiropractic,

- (2) Clinical indications for FLS radiography in chiropractic,

- (3) Risks associated with FLS radiography,

- (4) Chiropractic techniques which prescribe the use of FLS radiography,

- (5) Current trends in the utilisation of FLS radiography in chiropractic.

This review identified a paucity of literature addressing this issue and an underrepresentation of relevant perspectives from radiographers. Several issues surrounding the use of full-length spinal radiography by chiropractors were identified and examined, including barriers to the adherence to published guidelines for spinal imaging, an absence of a reporting mechanism for the utilization of spinal radiography in chiropractic and the existence of a spectrum of beliefs amongst chiropractors about the clinical utility and limitations of full-length spinal radiography.

The authors concluded that this review has identified a scarcity of literature addressing the completion of chiropractor‐referred FLS X‐rays. Our review has outlined several pressing issues that warrant further investigation including a lack of quantitative measures to assess the utilisation of FLS X‐rays by chiropractors, a lack of consensus of what constitutes appropriate clinical justification for imaging and the existence of a spectrum of beliefs amongst chiropractic authors about the clinical utility and limitations of FLS radiography. This provides radiographers with a definitive opportunity to demonstrate clinical leadership in this space and seek to begin a constructive dialogue with chiropractic referrers about the risks associated with unnecessary or unjustified spinal radiography. In doing this, diagnostic radiographers as evidence‐based health practitioners can actively contribute to the conversation surrounding the issues identified by this study and can be better positioned to advocate for the interests of the discipline and the safety of their patients.

The authors of this review make a number of further relevant points:

- Between 2014 and 2015, approximately 130,000 three‐ to four‐region spinal X‐rays were performed in Australia. Most were requested by chiropractors.

- In Australia, chiropractors often request FLS X‐ray examinations by radiographers.

- A spectrum of beliefs and knowledge exists amongst chiropractic practitioners surrounding the appropriate use of FLS radiography which may not always align with the principles of evidence‐based practice.

- The risks associated with the overutilization of diagnostic imaging are well documented. Aside from the inherent risks of unnecessary exposure to ionizing radiation, increased reliance on diagnostic imaging by any practitioner in the absence of sufficient clinical justification increases economic burdens encumbered upon the health care system. As such, FLS radiography should be used judiciously to ensure risks associated with its use are minimized, thus ensuring that it remains available to chiropractors and other practitioners where its use is clinically justified.

- Imaging that is not clinically indicated also carries a risk of overdiagnosis that being the radiological diagnosis of disease which does not ultimately impact on a patient’s course of treatment.

- The use of FLS radiography by chiropractors for the detection of red flags in the absence of any significant clinical indications for imaging could be considered a practice that carries a high risk of overdiagnosis.

When I first raised the issue of chiropractic overuse of imaging in 1998, I got fiercely attacked by a gang of chiros. Each time hence that I mention the subject, chiros loudly protest, and I do, of course, understand why. Imaging gives chiros the flair of being ‘cutting edge’; more importantly, in most countries, it is an easy source of additional income.

So, I do not expect that things will be different this time. Yet, I feel that, instead of constantly trying to shoot the messenger, chiropractors might be well advised to consider the message.

The purpose of this study was to examine the trends in the expenditure and utilization of chiropractic care in a representative sample of children and adolescents in the United States (US) aged <18 years.

The researchers evaluated serial cross-sectional data (2007-2016) from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Weighted descriptive statistics were conducted to derive national estimates of expenditure and utilization, and linear regression was used to determine trends over time. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of chiropractic users were also reported.

A statistically significant increasing trend was observed for the number of children receiving chiropractic care (P <.05) and chiropractic utilization rate (P < .05). Increases in chiropractic expenditure and the number of chiropractic visits were also observed over time but were not statistically significant (P > .05). The mean annual number of visits was 6.4 visits, with a mean expenditure of $71.49 US dollars (USD) per visit and $454.08 USD per child. Children and adolescent chiropractic users in the United States were primarily 14 to 17 years old (39.6%-61.6%), White (71.5%-76.9%), male (50.6%-51.3%), and privately insured (56.7%-60.8%). Chiropractic visits in this population primarily involved low back conditions (52.4%), spinal curvature (14.0%), and head and neck complaints (12.8%).

The authors concluded that the number of children visiting a chiropractor and percent utilization showed a statistically significant, increasing trend from 2007 to 2016; however, total expenditure and the number of chiropractic visits did not significantly differ during this period. These findings provide novel insight into the patterns of chiropractic utilization in this understudied age group.

Why are these numbers increasing?

Is it because of increasing and sound evidence showing that chiropractors do more good than harm to kids?

No!

A recent systematic review of the evidence for effectiveness and harms of specific spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) techniques for infants, and children suggests the opposite.

Its authors searched electronic databases up to December 2017. Controlled studies, describing primary SMT treatment in infants (<1 year) and children/adolescents (1–18 years), were included to determine effectiveness. Controlled and observational studies and case reports were included to examine harms. One author screened titles and abstracts and two authors independently screened the full text of potentially eligible studies for inclusion. Two authors assessed the risk of bias in included studies and the quality of the body of evidence using the GRADE methodology. Data were described according to PRISMA guidelines and CONSORT and TIDieR checklists. If appropriate, a random-effects meta-analysis was performed.

Of the 1,236 identified papers, 26 studies were eligible. In all but 3 studies, the therapists were chiropractors. Infants and children/adolescents were treated for various (non-)musculoskeletal indications, hypothesized to be related to spinal joint dysfunction. Studies examining the same population, indication, and treatment comparison were scarce. Due to very low-quality evidence, it is uncertain whether gentle, low-velocity mobilizations reduce complaints in infants with colic or torticollis, and whether high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulations reduce complaints in children/adolescents with autism, asthma, nocturnal enuresis, headache or idiopathic scoliosis. Five case reports described severe harms after HVLA manipulations in 4 infants and one child. Mild, transient harms were reported after gentle spinal mobilizations in infants and children and could be interpreted as a side effect of treatment.

The authors concluded that, based on GRADE methodology, we found the evidence was of very low quality; this prevented us from drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of specific SMT techniques in infants, children and adolescents. Outcomes in the included studies were mostly parent or patient-reported; studies did not report on intermediate outcomes to assess the effectiveness of SMT techniques in relation to the hypothesized spinal dysfunction. Severe harms were relatively scarce, poorly described and likely to be associated with underlying missed pathology. Gentle, low-velocity spinal mobilizations seem to be a safe treatment technique in infants, children and adolescents. We encourage future research to describe effectiveness and safety of specific SMT techniques instead of SMT as a general treatment approach.

But chiros do more than just SMT, I hear some say.

Yes, they do!

But they nevertheless manipulate virtually every patient, and the additional treatments they use are merely borrowed from other disciplines.

So, why are the numbers increasing then?

I suggest this as a main reason:

chiropractors are systematically misleading the public about the value of their trade.

Many systematic reviews have summarized the evidence on spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for low back pain (LBP) in adults. Much less is known about the older population regarding the effects of SMT. This paper assessed the effects of SMT on pain and function in older adults with chronic LBP in an individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis.

Electronic databases were searched from 2000 until June 2020; reference lists of eligible trials and related reviews were also searched. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were considered if they examined the effects of SMT in adults with chronic LBP compared to interventions recommended in international LBP guidelines. The authors of trials eligible for the IPD meta-analysis were contacted and invited to share data. Two review authors conducted a risk of bias assessment. Primary results were examined in a one-stage mixed model, and a two-stage analysis was conducted in order to confirm the findings. The main outcomes and measures were pain and functional status examined at 4, 13, 26, and 52 weeks.

A total of 10 studies were retrieved, including 786 individuals; 261 were between 65 and 91 years of age. There was moderate-quality evidence that SMT results in similar outcomes at 4 weeks (pain: mean difference [MD] – 2.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] – 5.78 to 0.66; functional status: standardized mean difference [SMD] – 0.18, 95% CI – 0.41 to 0.05). Second-stage and sensitivity analysis confirmed these findings.

The authors concluded that SMT provides similar outcomes to recommended interventions for pain and functional status in the older adult with chronic LBP. SMT should be considered a treatment for this patient population.

This is a fine analysis. Unfortunately, its results are less than fine. Its results confirm what I have been saying ad nauseam: we do not currently have a truly effective therapy for back pain, and most options are as good or as bad as the rest. This is most frustrating for everyone concerned, but it is certainly no reason to promote SMT as usually done by chiropractors or osteopaths.

The only logical solution, in my view, is to use those options that:

- are associated with the least risks,

- are the least expensive,

- are widely available.

However you twist and turn the existing evidence, the application of these criteria does not come up with chiropractic or osteopathy as an optimal solution. The best treatment is therapeutic exercise initially taught by a physiotherapist and subsequently performed as a long-term self-treatment by the patient at home.

Naprapathy is an odd variation of chiropractic. To be precise, it has been defined as a system of specific examination, diagnostics, manual treatment, and rehabilitation of pain and dysfunction in the neuromusculoskeletal system. It is aimed at restoring the function of the connective tissue, muscle- and neural tissues within or surrounding the spine and other joints. The evidence that it works is wafer-thin. Therefore rigorous studies are of interest.

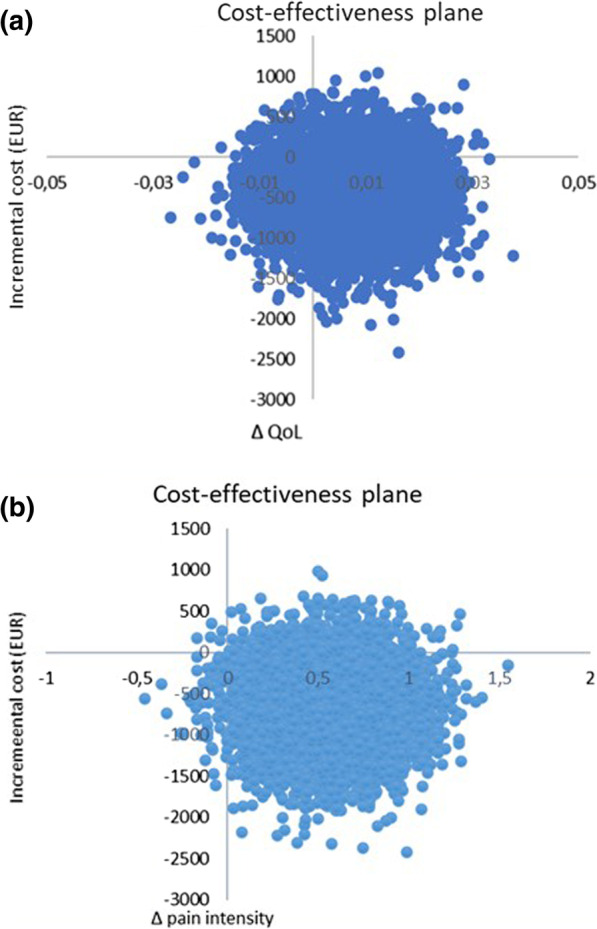

The aim of this study was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of manual therapy compared with advice to stay active for working-age persons with nonspecific back and/or neck pain.

The two interventions were:

- a maximum of 6 manual therapy sessions within 6 weeks, including spinal manipulation/mobilization, massage, and stretching, performed by a naprapath (index group),

- information from a physician on the importance to stay active and on how to cope with pain, according to evidence-based advice, on 2 occasions within 3 weeks (control group).

A cost-effectiveness analysis with a societal perspective was performed alongside a randomized controlled trial including 409 persons followed for one year, in 2005. The outcomes were health-related Quality of Life (QoL) encoded from the SF-36 and pain intensity. Direct and indirect costs were calculated based on intervention and medication costs and sickness absence data. An incremental cost per health-related QoL was calculated, and sensitivity analyses were performed.

The difference in QoL gains was 0.007 (95% CI – 0.010 to 0.023) and the mean improvement in pain intensity was 0.6 (95% CI 0.068-1.065) in favor of manual therapy after one year. Concerning the QoL outcome, the differences in mean cost per person were estimated at – 437 EUR (95% CI – 1302 to 371) and for the pain outcome the difference was – 635 EUR (95% CI – 1587 to 246) in favor of manual therapy. The results indicate that manual therapy achieves better outcomes at lower costs compared with advice to stay active. The sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main results.

Cost-effectiveness plane using bootstrapped incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for QoL and pain intensity outcomes

The authors concluded that these results indicate that manual therapy for nonspecific back and/or neck pain is slightly less costly and more beneficial than advice to stay active for this sample of working age persons. Since manual therapy treatment is at least as cost-effective as evidence-based advice from a physician, it may be recommended for neck and low back pain. Further health economic studies that may confirm those findings are warranted.

This is an interesting and well-conducted study. The differences between the groups seem small and of doubtful relevance. The authors acknowledge this fact by stating: “together with the clinical results from previously published studies on the same population the results suggest that manual therapy may be as cost-effective a treatment as evidence-based advice from a physician, for back and neck pain”. Moreover, the data do not convince me that the treatment per se was effective; it might have been the non-specific effects of touch and attention.

I have said it before: there is currently no optimal treatment for neck and back pain. Therefore, the findings even of rigorous cost-effectiveness studies will only generate lukewarm results.

Practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) often argue against treating back problems with drugs. They also frequently defend their own therapy by claiming it is backed by published guidelines. So, what should we think about guidelines for the management of back pain?

This systematic review was aimed at:

- systematically evaluating the literature for clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) that included the pharmaceutical management of non-specific LBP;

- appraising the methodological quality of the CPGs;

- qualitatively synthesizing the recommendations with the intent to inform non-prescribing providers who manage LBP.

The authors searched PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, Index to Chiropractic Literature, AMED, CINAHL, and PEDro to identify CPGs that described the management of mechanical LBP in the prior five years. Two investigators independently screened titles and abstracts and potentially relevant full text were considered for eligibility. Four investigators independently applied the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument for critical appraisal. Data were extracted for pharmaceutical intervention, the strength of recommendation, and appropriateness for the duration of LBP.

Only nine guidelines with global representation met the eligibility criteria. These CPGs addressed pharmacological treatments with or without non-pharmacological treatments. All CPGs focused on the management of acute, chronic, or unspecified duration of LBP. The mean overall AGREE II score was 89.3% (SD 3.5%). The lowest domain mean score was for applicability, 80.4% (SD 5.2%), and the highest was Scope and Purpose, 94.0% (SD 2.4%). There were ten classifications of medications described in the included CPGs: acetaminophen, antibiotics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, oral corticosteroids, skeletal muscle relaxants (SMRs), and atypical opioids.

The authors concluded that nine CPGs, included ten medication classes for the management of LBP. NSAIDs were the most frequently recommended medication for the treatment of both acute and chronic LBP as a first line pharmacological therapy. Acetaminophen and SMRs were inconsistently recommended for acute LBP. Meanwhile, with less consensus among CPGs, acetaminophen and antidepressants were proposed as second-choice therapies for chronic LBP. There was significant heterogeneity of recommendations within many medication classes, although oral corticosteroids, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, and antibiotics were not recommended by any CPGs for acute or chronic LBP.

Oddly, this review was published by chiros in a chiro journal. The authors mention that nearly all guidelines the included CPGs recommended non-pharmacological treatments for non-specific LBP, however it was not always delineated as to precede or be used in conjunction with pharmacological intervention.

I find the review interesting because I think it suggests that:

- CPGs are not the most reliable form of evidence. Their guidance depends on how up-to-date they are and on the identity and purpose of the authors.

- Guidelines are therefore often contradictory.

- Back pain is a symptom for which currently no optimal treatment exists.

- The most reliable evidence will rarely come from CPGs but from rigorous, up-to-date, independent systematic reviews such as those from the Cochrane Collaboration.

So, the next time chiropractors osteopaths, acupuncturists, etc. tell you “BUT MY THERAPY IS RECOMMENDED IN THE GUIDELINES”, please take it with a pinch of salt.

The objective of this study was to compare chronic low back pain patients’ perspectives on the use of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) compared to prescription drug therapy (PDT) with regard to health-related quality of life (HRQoL), patient beliefs, and satisfaction with treatment.

Four cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries were assembled according to previous treatment received as evidenced in claims data:

- The SMT group began long-term management with SMT but no prescribed drugs.

- The PDT group began long-term management with prescription drug therapy but no spinal manipulation.

- This group employed SMT for chronic back pain, followed by initiation of long-term management with PDT in the same year.

- This group used PDT for chronic back pain followed by initiation of long-term management with SMT in the same year.

A total of 1986 surveys were sent out and 195 participants completed the survey. The respondents were predominantly female and white, with a mean age of approx. 77-78 years. Outcome measures used were a 0-to-10 numeric rating scale to measure satisfaction, the Low Back Pain Treatment Beliefs Questionnaire to measure patient beliefs, and the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey to measure HRQoL.

Recipients of SMT were more likely to be very satisfied with their care (84%) than recipients of PDT (50%; P = .002). The SMT cohort self-reported significantly higher HRQoL compared to the PDT cohort; mean differences in physical and mental health scores on the 12-item Short Form Health Survey were 12.85 and 9.92, respectively. The SMT cohort had a lower degree of concern regarding chiropractic care for their back pain compared to the PDT cohort’s reported concern about PDT (P = .03).

The authors concluded that among older Medicare beneficiaries with chronic low back pain, long-term recipients of SMT had higher self-reported rates of HRQoL and greater satisfaction with their modality of care than long-term recipients of PDT. Participants who had longer-term management of care were more likely to have positive attitudes and beliefs toward the mode of care they received.

The main issue here is that the ‘study’ was a mere survey which by definition cannot establish cause and effect. The groups were different in many respects which rendered them not comparable. For instance, participants who received SMT had higher self-reported physical and mental health on average than those who received PDT. Differences also existed between the SMT and the PDT groups for agreement with the notion that “spinal manipulation for LBP makes a lot of sense”; 96% of the SMT group and 35% of the PDT group agreed with it. Compare this with another statement, “taking /having prescription drug therapy for LBP makes a lot of sense” and we find that only 13% of the SMT cohort agreed with, 95% of the PDT cohort agreed. Thus, a powerful bias exists toward the type of therapy that each person had chosen. Another determinant of the outcome is the fact that SMT means hands-on treatments with time, compassion, and empathy given to the patient, whereas PDT does not necessarily include such features. Add to these limitations the dismal response rate, recall bias, and numerous potential confounders and you have a survey that is hardly worth the paper it is printed on. In fact, it is little more than a marketing exercise for chiropractic.

In summary, the findings of this survey are influenced by a whole range of known and unknown factors other than the SMT. The authors are clever to avoid causal inferences in their conclusions. I doubt, however, that many chiropractors reading the paper think critically enough to do the same.

This study describes the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) among older adults who report being hampered in daily activities due to musculoskeletal pain. The characteristics of older adults with debilitating musculoskeletal pain who report SCAM use is also examined. For this purpose, the cross-sectional European Social Survey Round 7 from 21 countries was employed. It examined participants aged 55 years and older, who reported musculoskeletal pain that hampered daily activities in the past 12 months.

Of the 4950 older adult participants, the majority (63.5%) were from the West of Europe, reported secondary education or less (78.2%), and reported at least one other health-related problem (74.6%). In total, 1657 (33.5%) reported using at least one SCAM treatment in the previous year.

The most commonly used SCAMs were:

- manual body-based therapies (MBBTs) including massage therapy (17.9%),

- osteopathy (7.0%),

- homeopathy (6.5%)

- herbal treatments (5.3%).

SCAM use was positively associated with:

- younger age,

- physiotherapy use,

- female gender,

- higher levels of education,

- being in employment,

- living in West Europe,

- multiple health problems.

(Many years ago, I have summarized the most consistent determinants of SCAM use with the acronym ‘FAME‘ [female, affluent, middle-aged, educated])

The authors concluded that a third of older Europeans with musculoskeletal pain report SCAM use in the previous 12 months. Certain subgroups with higher rates of SCAM use could be identified. Clinicians should comprehensively and routinely assess SCAM use among older adults with musculoskeletal pain.

I often mutter about the plethora of SCAM surveys that report nothing meaningful. This one is better than most. Yet, much of what it shows has been demonstrated before.

I think what this survey confirms foremost is the fact that the popularity of a particular SCAM and the evidence that it is effective are two factors that are largely unrelated. In my view, this means that more, much more, needs to be done to inform the public responsibly. This would entail making it much clearer:

- which forms of SCAM are effective for which condition or symptom,

- which are not effective,

- which are dangerous,

- and which treatment (SCAM or conventional) has the best risk/benefit balance.

Such information could help prevent unnecessary suffering (the use of ineffective SCAMs must inevitably lead to fewer symptoms being optimally treated) as well as reduce the evidently huge waste of money spent on useless SCAMs.

There is hardly a form of therapy under the SCAM umbrella that is not promoted for back pain. None of them is backed by convincing evidence. This might be because back problems are mostly viewed in SCAM as mechanical by nature, and psychological elements are thus often neglected.

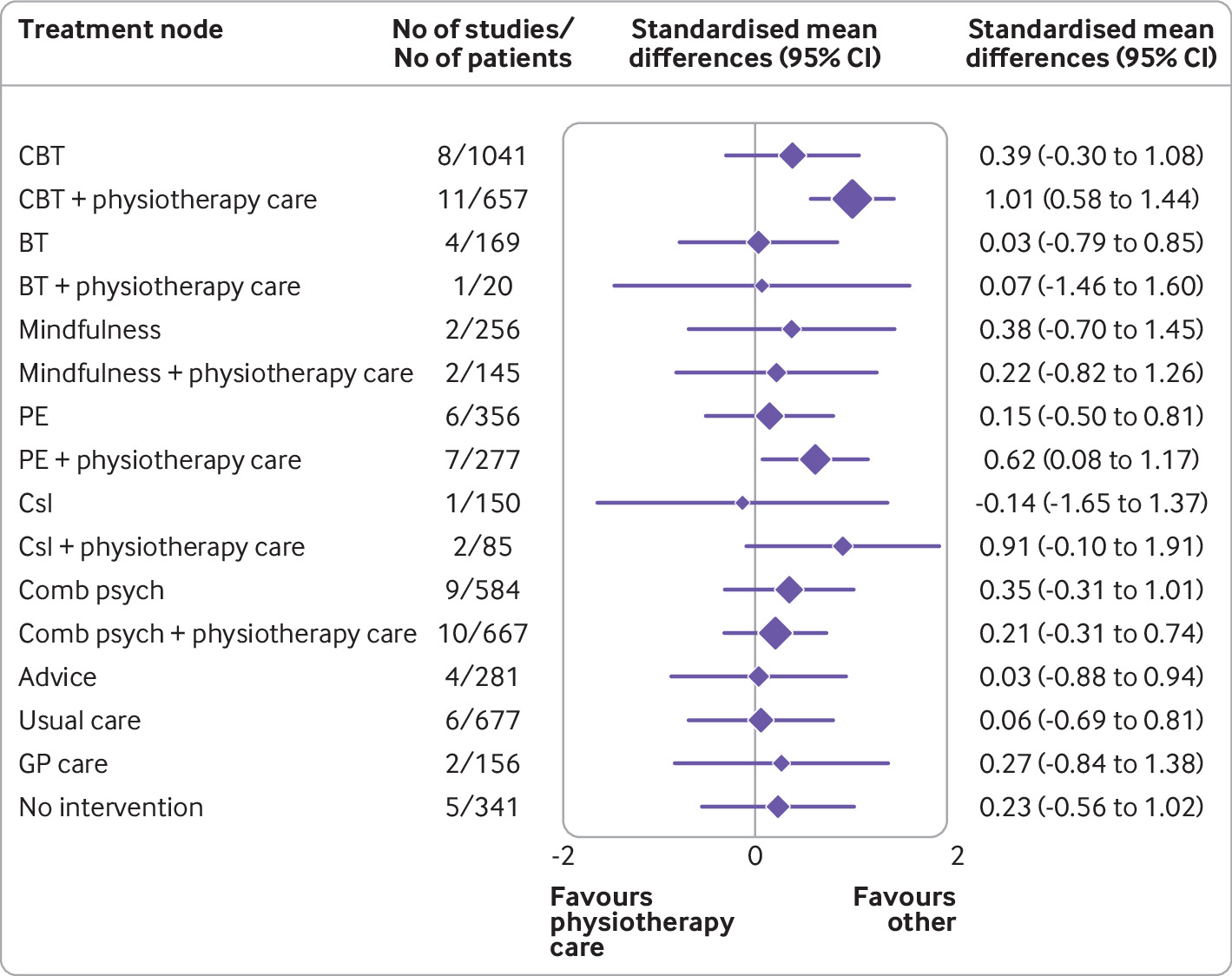

This systematic review with network meta-analysis determined the comparative effectiveness and safety of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Randomised controlled trials comparing psychological interventions with any comparison intervention in adults with chronic, non-specific low back pain were included.

A total of 97 randomised controlled trials involving 13 136 participants and 17 treatment nodes were included. Inconsistency was detected at short term and mid-term follow-up for physical function, and short term follow-up for pain intensity, and were resolved through sensitivity analyses. For physical function, cognitive behavioural therapy (standardised mean difference 1.01, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 1.44), and pain education (0.62, 0.08 to 1.17), delivered with physiotherapy care, resulted in clinically important improvements at post-intervention (moderate-quality evidence). The most sustainable effects of treatment for improving physical function were reported with pain education delivered with physiotherapy care, at least until mid-term follow-up (0.63, 0.25 to 1.00; low-quality evidence). No studies investigated the long term effectiveness of pain education delivered with physiotherapy care. For pain intensity, behavioural therapy (1.08, 0.22 to 1.94), cognitive behavioural therapy (0.92, 0.43 to 1.42), and pain education (0.91, 0.37 to 1.45), delivered with physiotherapy care, resulted in clinically important effects at post-intervention (low to moderate-quality evidence). Only behavioural therapy delivered with physiotherapy care maintained clinically important effects on reducing pain intensity until mid-term follow-up (1.01, 0.41 to 1.60; high-quality evidence).

Forest plot of network meta-analysis results for physical function at post-intervention. *Denotes significance at p<0.05. BT=behavioural therapy; CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy; Comb psych=combined psychological approaches; Csl=counselling; GP care=general practitioner care; PE=pain education; SMD=standardised mean difference. Physiotherapy care was the reference comparison group

The authors concluded that for people with chronic, non-specific low back pain, psychological interventions are most effective when delivered in conjunction with physiotherapy care (mainly structured exercise). Pain education programmes (low to moderate-quality evidence) and behavioural therapy (low to high-quality evidence) result in the most sustainable effects of treatment; however, uncertainty remains as to their long term effectiveness. Although inconsistency was detected, potential sources were identified and resolved.

The authors’ further comment that their review has identified that pain education, behavioural therapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy are the most effective psychological interventions for people with chronic, non-specific LBP post-intervention when delivered with physiotherapy care. The most sustainable effects of treatment for physical function and fear avoidance are achieved with pain education programmes, and for pain intensity, they are achieved with behavioural therapy. Although their clinical effectiveness diminishes over time, particularly in the long term (≥12 months post-intervention), evidence supports the clinical benefits of combining physiotherapy care with these specific types of psychological interventions at the onset of treatment. The small total sample size at long term follow-up (eg, for physical function, n=6986 at post-intervention v n=2469 for long term follow-up; for pain intensity, n=6963 v n=2272) has resulted in wide confidence intervals at this time point; however, the magnitude and direction of the pooled effects seemed to consistently favour the psychological interventions delivered with physiotherapy care, compared with physiotherapy care alone.

Commenting on their paper, two of the authors, Ferriera and Ho, said they would like to see the guidelines on LBP therapy updated to provide more specific recommendations, the “whole idea” is to inform patients, so they can have conversations with their GP or physiotherapist. Patients should not come to consultations with a passive attitude of just receiving whatever people tell them because unfortunately people still receive the wrong care for chronic back pain,” Ferreira says. “Clinicians prescribe anti-inflammatories or paracetamol. We need to educate patients and clinicians about options and more effective ways of managing pain.”

Is there a lesson here for patients consulting SCAM practitioners for their back pain? Perhaps it is this: it is wise to choose the therapy that has been demonstrated to be effective while having the least potential for harm! And this is not chiropractic or any other form of SCAM. It could, however, well be a combination of physiotherapeutic exercise and psychological therapy.

An article in PULSE entitled ‘ Revolutionising Chiropractic Care for Today’s Healthcare System’ deserves a comment, I think. Here I give you first the article followed by my comments. The references in square brackets refer to the latter and were inserted by me; otherwise, the article is unchanged.

___________________________

This Chiropractic Awareness Week (4th – 10th April), Catherine Quinn, President of the British Chiropractic Association (BCA), is exploring the opportunity and need for a more integrated healthcare eco-system, putting the spotlight on how chiropractors can help alleviate pressures and support improved patient outcomes.

Chiropractic treatment and its role within today’s health system often prompts questions and some debate – what treatments fit under chiropractic care? Is the profession evidence based? How can it support primary health services, with the blend of public and private practice in mind? This Chiropractic Awareness Week, I want to address these questions and share the British Chiropractic Association’s ambition for the future of the profession.

The role of chiropractic today

The need for effective and efficient musculoskeletal (MSK) treatment is clear – in the UK, an estimated 17.8 million people live with a MSK condition, equivalent to approximately 28.9% of the total population.1 Lower back and neck pain specifically are the greatest causes of years lost to disability in the UK, with chronic joint pain or osteoarthritis affecting more than 8.75 million people.2 In addition to this, musculoskeletal conditions also account for 30% of all GP appointments, placing immense pressure on a system which is already under stress.3 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is still being felt by these patients and their healthcare professionals alike. Patients with MSK conditions are still having their care impacted by issues such as having clinic appointments cancelled, difficulty in accessing face-to-face care and some unable to continue regular prescribed exercise.

With these numbers and issues in mind, there is a lot of opportunity to more closely integrate chiropractic within health and community services to help alleviate pressures on primary care [1]. This is something we’re really passionate about at the BCA. However, we recognise that there are varying perceptions of chiropractic care – not just from the public but across our health peers too. We want to address this, so every health discipline has a consistent understanding.

First and foremost, chiropractic is a registered primary healthcare profession [2] and a safe form of treatment [3], qualified individuals in this profession are working as fully regulated healthcare professionals with at least four years of Masters level training. In the UK, chiropractors are regulated by law and required to adhere to strict codes of practice [4], in exactly the same ways as dentists and doctors [5]. At the BCA we want to represent the highest quality chiropractic care, which is encapsulated by a patient centred approach, driven by evidence and science [6].

As a patient-first organisation [7], our primary goal is to equip our members to provide the best treatment possible for those who need our care [8]. We truly believe that working collaboratively with other primary care and NHS services is the way to reach this goal [9].

The benefits of collaborative healthcare

As chiropractors, we see huge potential in working more closely with primary care providers and recognise there’s mutual benefits for both parties [10]. Healthcare professionals can tap into chiropractors’ expertise in MSK conditions, leaning on them for support with patient caseloads. Equally, chiropractors can use the experience of working with other healthcare experts to grow as professionals.

At the BCA, our aim is to grow this collaborative approach, working closely with the wider health community to offer patients the best level of care that we can [11]. Looking at primary healthcare services in the UK, we understand the pressures that individual professionals, workforces, and organisations face [12]. We see the large patient rosters and longer waiting times and truly believe that chiropractors can alleviate some of those stresses by treating those with MSK concerns [13].

One way the industry is beginning to work in a more integrated way is through First Contact Practitioners (FCPs) [14]. These are healthcare professionals like chiropractors who provide the first point of contact to GP patients with MSK conditions [15]. We’ve already seen a lot of evidence showing that primary care services using FCPs have been able to improve quality of care [16]. Through this service MSK patients are also seeing much shorter wait times for treatment (as little as 2-3 days), so the benefits speak for themselves for both the patient and GP [17].

By working as part of an integrated care model, with chiropractors, GPs, physiotherapists and other medical professionals, we’re creating a system that provides patients with direct routes to the treatments that they need, with greater choice. Our role within this system is very much to contribute to the health of our country, support primary care workers and reinforce the incredible work of the NHS [18].

Overcoming integrated healthcare challenges

To continue to see the chiropractic sector develop over the coming years, it’s important for us to face some of the challenges currently impacting progress towards a more integrated healthcare service.

One example is that there is a level of uncertainty about where chiropractic sits in the public/private blend. This is something we’re ready to tackle head on by showing exactly how chiropractic care benefits different individuals, whether that’s through reducing pain, improving physical function or increasing mobility [19]. We also need to encourage more awareness amongst both chiropractors and other healthcare providers about how an integrated workforce could benefit medical professionals and patients alike [20]. For example, there’s only two FCP chiropractors to date, and that’s something we’re looking to change [14].

This is the start of a much bigger conversation and, at the BCA, we’ll continue to work on driving peer acceptance, trust and inclusion to demonstrate the value of our place within the healthcare industry [21]. We’re ready to support the wider health community and primary carers, alleviating some of the pressures already facing the NHS; we’re placed in the perfect position as we have the knowledge and experience to provide essential support [22]. My main takeaway from this year’s Chiropractic Awareness Week would be to simply start a conversation with us about how [23].

About the British Chiropractic Association:

The BCA is the largest and longest-standing association for chiropractors in the UK. As well as promoting international standards of education and exemplary conduct, the BCA supports chiropractors to progress and develop to fulfil their professional ambitions with honour and integrity, at every step [24]. This Chiropractic Awareness Week, the BCA is raising awareness about the rigour, relevance and evidence driving the profession and the association’s ambition for chiropractic to be more closely embedded within mainstream healthcare [25].

- https://bjgp.org/content/70/suppl_1/bjgp20X711497

- https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/data-and-statistics/the-state-of-musculoskeletal-health/

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/elective-care-transformation/best-practice-solutions/musculoskeletal/#:~:text=Musculoskeletal%20(MSK)%20conditions%20account%20for,million%20people%20in%20the%20UK

__________________________________

And here are my comments:

- Non sequitur = a conclusion or statement that does not logically follow from the previous argument or statement.

- A primary healthcare profession is a profession providing primary healthcare which, according to standard definitions, is the provision of health services, including diagnosis and treatment of a health condition, and support in managing long-term healthcare, including chronic conditions like diabetes. Thus chiropractors are not in that category.

- This is just wishful thinking. Chiropractic spinal manipulation is not safe!

- “Required to adhere to strict codes of practice”. Required yes, but how often do they not comply?

- This is not true.

- Chiropractic is very far from being “driven by evidence and science”.

- Platitude = a remark or statement, especially one with a moral content, that has been used too often to be interesting or thoughtful.

- Judging from past experience, the primary goal seems to be to protect chiropractors (see, for instance, here).

- Belief is for religion, in healthcare you need evidence. Have you looked at the referral rates of chiropractors to GPs, for instance?

- For chiropractors, the benefit is usually measured in £s.

- To offer the ” best level of care” you need research and evidence, not politically correct statements.

- Platitude = a remark or statement, especially one with a moral content, that has been used too often to be interesting or thoughtful.

- Belief is for religion, in healthcare you need evidence.

- First Contact Practitioners are “regulated, advanced and autonomous health CARE PROFESSIONALS who are trained to provide expert PATIENT assessment, diagnosis and first-line treatment, self-care advice and, if required, appropriate onward referral to other SERVICES.” I doubt that many chiropractors fulfill these criteria.

- Not quite; see above.

- “A lot of evidence”? Really? Where is it?

- “The benefits speak for themselves” only if the treatments used are evidence-based.

- Platitude = a remark or statement, especially one with a moral content, that has been used too often to be interesting or thoughtful.

- Where is the evidence?

- Awareness is not needed as much as evidence?

- Platitude = a remark or statement, especially one with a moral content, that has been used too often to be interesting or thoughtful.

- Platitude = a remark or statement, especially one with a moral content, that has been used too often to be interesting or thoughtful.

- Fine, let’s start the conversation: where is your evidence?

- Judging from past experience honor and integrity seem rather thin on the ground (see, for instance here).

The article promised to ‘revolutionize chiropractic care and to answer questions like what treatments fit under chiropractic care? Is the profession evidence-based? Sadly, none of this emerged. Instead, we were offered politically correct platitudes, half-truths, and obscurations.

The revolution in chiropractic, it thus seems, is not in sight.

Today, several UK dailies report about a review of osteopathy just published in BMJ-online. The aim of this paper was to summarise the available clinical evidence on the efficacy and safety of osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) for different conditions. The authors conducted an overview of systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses (MAs). SRs and MAs of randomised controlled trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of OMT for any condition were included.

The literature searches revealed nine SRs or MAs conducted between 2013 and 2020 with 55 primary trials involving 3740 participants. The SRs covered a wide range of conditions including

- acute and chronic non-specific low back pain (NSLBP, four SRs),

- chronic non-specific neck pain (CNSNP, one SR),

- chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP, one SR),

- paediatric (one SR),

- neurological (primary headache, one SR),

- irritable bowel syndrome (IBS, one SR).

Although with different effect sizes and quality of evidence, MAs reported that OMT is more effective than comparators in reducing pain and improving the functional status in acute/chronic NSLBP, CNSNP and CNCP. Due

to the small sample size, presence of conflicting results and high heterogeneity, questionable evidence existed on OMT efficacy for paediatric conditions, primary headaches and IBS. No adverse events were reported in most SRs. The methodological quality of the included SRs was rated low or critically low.

The authors concluded that based on the currently available SRs and MAs, promising evidence suggests the possible effectiveness of OMT for musculoskeletal disorders. Limited and inconclusive evidence occurs for paediatric conditions, primary headache and IBS. Further well-conducted SRs and MAs are needed to confirm and extend the efficacy and safety of OMT.

This paper raises several questions. Here a just the two that bothered me most:

- If the authors had truly wanted to evaluate the SAFETY of OMT (as they state in the abstract), they would have needed to look beyond SRs, MAs or RCTs. We know – and the authors of the overview confirm this – that clinical trials of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) often fail to mention adverse effects. This means that, in order to obtain a more realistic picture, we need to look at case reports, case series and other observational studies. It also means that the positive message about safety generated here is most likely misleading.

- The authors (the lead author is an osteopath) might have noticed that most – if not all – of the positive SRs were published by osteopaths. Their assessments might thus have been less than objective. The authors did not include one of our SRs (because it fell outside their inclusion period). Yet, I do believe that it is one of the few reviews of OMT for musculoskeletal problems that was not done by osteopaths. Therefore, it is worth showing you its abstract here:

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of osteopathy as a treatment option for musculoskeletal pain. Six databases were searched from their inception to August 2010. Only randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were considered if they tested osteopathic manipulation/mobilization against any control intervention or no therapy in human with any musculoskeletal pain in any anatomical location, and if they assessed pain as an outcome measure. The selection of studies, data extraction, and validation were performed independently by two reviewers. Studies of chiropractic manipulations were excluded. Sixteen RCTs met the inclusion criteria. Their methodological quality ranged between 1 and 4 on the Jadad scale (max = 5). Five RCTs suggested that osteopathy compared to various control interventions leads to a significantly stronger reduction of musculoskeletal pain. Eleven RCTs indicated that osteopathy compared to controls generates no change in musculoskeletal pain. Collectively, these data fail to produce compelling evidence for the effectiveness of osteopathy as a treatment of musculoskeletal pain.

It was published 11 years ago. But I have so far not seen compelling evidence that would make me change our conclusion. As I state in the newspapers:

OSTEOPATHY SHOULD BE TAKEN WITH A SIZABLE PINCH OF SALT.