ethics

The fact that practitioners of alternative medicine frequently advise their patients against immunising their children has been documented repeatedly. In particular, doctors of anthroposophy, chiropractors and homeopaths are implicated in thus endangering public health. Less is known about naturopaths attitude in this respect. Now new data have emerged which confirm some of our worst fears.

This survey aimed at assessing the attitudes, education, and sources of knowledge surrounding childhood vaccinations of 560 students at National College of Natural Medicine in Portland, US. Students were asked about demographics, sources of information about childhood vaccines, differences between mainstream and CAM education on childhood vaccines, alternative vaccine schedules, adverse effects, perceived efficacy, and credibility of information sources.

A total of 109 students provided responses (19.4% response rate). All students surveyed learned about vaccinations in multiple courses and through independent study. The information sources employed had varying levels of credibility. Only 26% of the responding students planned on regularly prescribing or recommending vaccinations for their patients; 82% supported the general concept of vaccinations for prevention of infectious diseases.

The vast majority (96%) of those who might recommend vaccinations reported that they would only recommend a schedule that differed from the standard CDC-ACIP schedule.

Many respondents were concerned about vaccines being given too early (73%), too many vaccines administered simultaneously (70%), too many vaccines overall (59%), and about preservatives and adjuvants in vaccines (72%). About 40% believed that a healthy diet and lifestyle was more important for prevention of infectious diseases than vaccines. 90% admitted that they were more critical of vaccines than mainstream pediatricians, medical doctors, and medical students.

These results speak for themselves and leave me (almost) speechless. The response rate was truly dismal, and it is fair to assume that the non-responding students held even more offensive views on vaccination than their responding colleagues. The findings seem to indicate that naturopaths are systematically trained to become anti-vaxers who believe that their naturopathic treatments offer better protection than vaccines. They are thus depriving many of their patients of arguably the most successful means of disease prevention that exists today. To put it bluntly: naturopaths seem to be brain-washed into becoming a danger to public health.

Today, there are several dozens of journals publishing articles on alternative medicine. ‘The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine’ is one of the best known, and it has one of the highest impact factors of them all. The current issue holds a few ‘gems’ which might be worthy of a comment or two. Here I have selected three articles reporting clinical studies, and I reproduce their abstracts (almost) in full (in italics) and add my comments (for clarity in bold). All the articles are available electronically, and I have provided the links for those who want to investigate beyond the abstracts.

STUDY No 1

The first ‘pilot study‘ was aimed to demonstrate the potential of auricular acupuncture (AAT) for insomnia in maintenance haemodialysis (MHD) patients and to prepare for a future randomized controlled trial.

Eligible patients were enrolled into this descriptive pilot study and received AAT designed to manage insomnia for 4 weeks. Questionnaires that used the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) were completed at baseline, after a 4-week intervention, and 1 month after completion of treatment. Sleep quality and other clinical characteristics, including sleeping pills taken, were statistically compared between different time points.

A total of 22 patients were selected as eligible participants and completed the treatment and questionnaires. The mean global PSQI score was significantly decreased after AAT intervention (p<0.05). Participants reported improved sleep quality (p<0.01), shorter sleep latency (p<0.05), less sleep disturbance (p<0.01), and less daytime dysfunction (p=0.01). They also exhibited less dependency on sleep medications, indicated by the reduction in weekly estazolam consumption from 6.98±4.44 pills to 4.23±2.66 pills (p<0.01). However, these improvements were not preserved 1 month after treatment.

Conclusions: In this single-center pilot study, complementary AAT for MHD patients with severe insomnia was feasible and well tolerated and showed encouraging results for sleep quality.

My comments:

In alternative medicine research, it has become far too common (almost generally accepted) to call a flimsy trial a ‘pilot study’. The authors give their game away by stating that, by conducting this trial, they want to ‘demonstrate the potential of AAT’. This is not a legitimate aim of research; science is for TESTING hypotheses, not for PROVING them!

The results of this trial show that patients experienced improvements after receiving AAT which, however, did not last. As there was no placebo control group, the most likely explanation for these outcomes would be that AAT generated a short-lasting placebo effect.

A sample size of 22 is, of course, far to small to allow any conclusions about the safety of the intervention. Despite these obvious facts, the authors seem convinced that AAT is both safe and effective.

STUDY No 2

The aim of the second study was to compare the therapeutic effect of Yamamoto new scalp acupuncture (YNSA), a recently developed microcupuncture system, with traditional acupuncture (TCA) for the prophylaxis and treatment of migraine headache.

In a randomized clinical trial, 80 patients with migraine headache were assigned to receive YNSA or TCA. A pain visual analogue scale (VAS) and migraine therapy assessment questionnaire (MTAQ) were completed before treatment, after 6 and 18 sections of treatment, and 1 month after completion of therapy.

All the recruited patients completed the study. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups. Frequency and severity of migraine attacks, nausea, the need for rescue treatment, and work absence rate decreased similarly in both groups. Recovery from headache and ability to continue daily activities 2 hours after medical treatment showed similar improvement in both groups (p>0.05).

Conclusions: Classic acupuncture and YNSA are similarly effective in the prophylaxis and treatment of migraine headache and may be considered as alternatives to pharmacotherapy.

My comments:

This is what is technically called an ‘equivalence trial’, i.e. a study that compares an experimental treatment (YNSA) to one that is (assumed to be) effective. To demonstrate equivalence, such trials need to have large sample sizes, and this study is woefully underpowered. As it stands, the results show nothing meaningful at all; if anything, they suggest that both interventions were similarly useless.

STUDY No 3

The third study determined whether injection with hypertonic dextrose and morrhuate sodium (prolotherapy) using a pragmatic, clinically determined injection schedule for knee osteoarthritis (KOA) results in improved knee pain, function, and stiffness compared to baseline status.

The participants were 38 adults who had at least 3 months of symptomatic KOA and who were in the control groups of a prior prolotherapy randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Prior-Control), were ineligible for the RCT (Prior-Ineligible), or were eligible but declined the RCT (Prior-Declined).

The injection sessions at occurred at 1, 5, and 9 weeks with as-needed treatment at weeks 13 and 17. Extra-articular injections of 15% dextrose and 5% morrhuate sodium were done at peri-articular tendon and ligament insertions. A single intra-articular injection of 6 mL 25% dextrose was performed through an inferomedial approach.

The primary outcome measure was the validated Western Ontario McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC). The secondary outcome measure was the Knee Pain Scale and postprocedure opioid medication use and participant satisfaction.

The Prior-Declined group reported the most severe baseline WOMAC score (p=0.02). Compared to baseline status, participants in the Prior-Control group reported a score change of 12.4±3.5 points (19.5%, p=0.002). Prior-Decline and Prior-Ineligible groups improved by 19.4±7.0 (42.9%, p=0.05) and 17.8±3.9 (28.4%, p=0.008) points, respectively; 55.6% of Prior-Control, 75% of Prior-Decline, and 50% of Prior-Ineligible participants reported score improvement in excess of the 12-point minimal clinical important difference on the WOMAC measure. Postprocedure opioid medication resulted in rapid diminution of prolotherapy injection pain. Satisfaction was high and there were no adverse events.

Conclusions: Prolotherapy using dextrose and morrhuate sodium injections for participants with mild-to-severe KOA resulted in safe, significant, sustained improvement of WOMAC-based knee pain, function, and stiffness scores compared to baseline status.

My Comments:

This study had nothing that one might call a proper control group: all the three groups mentioned were treated with the experimental treatment. No attempt was made to control for even the most obvious biases: the observed effects could have been due to placebo or any other non-specific effects. The authors conclusions imply a causal relationship between the treatment and the outcome which is wrong. The notion that the experimental treatment is ‘safe’ is based on just 38 patients and therefore not reasonable.

IMPLICATION

All of this might seem rather trivial, and my comments could be viewed as a deliberate and vicious attempt to discredit one of the most respected journals of alternative medicine. Yet, considering that articles of this nature are more the rule than the exception in alternative medicine, I do think that this flagrant lack of scientific rigour is a relevant issue and has important implications.

As long as research in this area continues to be deeply flawed, as long as reviewers turn a blind eye to (or are not smart enough to detect) even the most obvious mistakes, as long as journal editors accept any rubbish in order to fill their pages, there is a great danger that we are being continuously being mislead about the supposed therapeutic value of alternative therapies.

Many who read this blog will, of course, have the capacity to think critically and might therefore not fall into the trap of accepting the conclusions of fatally flawed research. But many other people, including politicians, journalists and consumers, might not have the necessary appraisal skills and will thus not be able to tell that such studies can serve only one purpose: to popularise bogus treatments and thereby render health care less effective and more dangerous. Enthusiasts of alternative medicine are usually fully convinced that such studies amount to evidence and ram this pseudo-information down the throat of health care decision makers – the effects of such lobbying on public health can be disastrous.

And there is another downside to the publication of such dismal drivel: assuming (as I do) that not all of alternative medicine is completely useless, such embarrassingly poor research will inevitably have detrimental effects on the discipline of alternative medicine. After being exposed to a seemingly endless stream of pseudo-research, critics will eventually give up taking any of it seriously and might claim that none of it is worth the bother. In other words, those who conduct, accept or publish such nonsensical papers are not only endangering medical progress in general, they are also harming the very cause they try so desperately hard to advance.

I have often asked myself whether it is right/necessary to scientifically test things which are entirely implausible. Should we, for instance test the effectiveness of treatments which have a very low prior probability of generating a positive effect such as paranormal healing, homeopathy or Bach flower remedies? If you believe in the principles of evidence-based medicine you might focus on the clinical evidence and see biological plausibility as secondary. If you are a basic scientist, you are likely to do the reverse.

A recent article addressed this issue. The author points out that evaluating the absurd is absurd. Specifically, he noted that the empirical evaluation of a therapy would normally assume a plausible rationale regarding the mechanism of action. However, examination of the historical background and underlying principles for reflexology, iridology, acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, and some herbal medicines, reveals a rationale founded on the principle of analogical correspondences, which is a common basis for magical thinking and pseudoscientific beliefs such as astrology and chiromancy. Where this is the case, it is suggested that subjecting these therapies to empirical evaluation may be tantamount to evaluating the absurd.

This makes a lot of sense – but is it really entirely true? Are there no legitimate reasons at all for testing alternative treatments that lack biological plausibility? Ten or twenty years ago, I would have disagreed with the notion that plausibility is an essential prerequisite for scientific testing; today, I have changed my mind a little, but not as much as to agree completely with the assumption. In other words, I still see more than one good reason why evaluating the absurd might be reasonable or even advisable.

- Using plausibility as the only arbiter of scientific ‘evaluability’, assumes that we understand everything about plausibility there is to know. Yet it might just be possible that we mis-categorise something as implausible simply because we are not yet fully aware of all the facts.

- Declaring something as plausible and another thing as implausible are not hard and fast verdicts but judgements which, at least to some degree, are subjective. Sceptics find the axioms of homeopathy utterly implausible, for instance – but ask a homeopath, and you will hear all sorts of explanations which, at least to them, sound plausible.

- If an implausible alternative treatment is in wide-spread use, we arguably have a responsibility to test it scientifically in order to demonstrate the truth about it (to those proponents of that therapy who are willing to accept that rigorous science can find the truth). If we fail to do this, it will be the enthusiasts of that therapy who conduct less than rigorous science and produce false positive results. In turn, this will give the impression that the treatment is effective and mislead consumers, politicians, journalists etc. Seen from this perspective, it might even be unethical to not do the science.

So, I am in two minds about this (which might be a reflection of the fact that, during different periods of my life, I have been a clinician, a basic scientist and a clinical researcher). I realise that plausibility and prior probability are important – much more so than I appreciated years ago. But I think they should not be the only criteria. The clinical evidence should not be pushed aside completely.

I’d be interested to learn your views on this tricky issue.

It has been reported that Belgium has just officially recognised homeopathy. The government had given the green light already in July last year, but the Royal Decree has only now become official. This means that, from now on, Belgian doctors, dentists and midwives can only call themselves homeopaths, if they have attended recognised courses in homeopathy and are officially certified. While much of the new regulation is as yet unclear (at least to me), it seems that, in future, only doctors, dentists and midwives are allowed to practice homeopathy, according to one source.

However, the new law also seems to provide that those clinicians with a Bachelor degree in health care who have already been practicing as homeopaths can continue their activities under a temporary measure.

Moreover, the official recognition as a homeopath does not automatically imply that the services will be refunded from a health insurance.

It is said that, in general, homeopaths are happy with the new regulation; they are delighted to have been up-graded in this way and argue that the changes will result in higher quality standards: “This is a very important step and it can only be to the benefit of the patients’ safety. Patients will know whether or not they are dealing with someone who correctly applies homeopathic medicine”, Leon Schepers of the Unio Homeopathica Belgica was quoted saying.

The delight of homeopaths is in sharp contrast to the dismay of rational thinkers. The NHMRC recently assessed the effectiveness of homeopathy. The evaluation is both comprehensive and independent; it concluded that “the evidence from research in humans does not show that homeopathy is effective for treating the range of health conditions considered.” In other words, homeopathic remedies are implausible, over-priced placebos.

Granting an official status to homeopaths cannot possibly benefit patients. On the contrary, it will only render health care less effective and charlatans more assertive.

Guest post by Michelle Dunbar

According to the CDC, more than 30,000 people died as a result of a drug overdose in 2010. Of those deaths none were attributed to marijuana. Instead the vast majority were linked to drugs that are legally prescribed such as opiates, anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, tranquilizers and benzodiazepines. As misuse and abuse of prescription medications continues to rise, the marijuana legalization debate is also heating up.

Nearly 100 years of propaganda, fear mongering and blatant misinformation regarding marijuana has taken its toll on our society. As the veil of lies surrounding marijuana is being lifted, more and more people are pushing for legalization. Marijuana is now legal for both medicinal and recreational use in two states and other states are introducing legislation of their own. Marijuana is approved for medicinal use with a prescription in 21 states and also Washington, D.C. with most other states expected to introduce legislation to approve use for medicinal purposes in the next few years.

Last year Dr. Sanjay Gupta, the medical correspondent for CNN, aired a controversial documentary, “Weed”, where he showed various promising medicinal uses for marijuana. He admits that he was wrong for many years about marijuana legalization, and after doing his own extensive research he is encouraged by the many real life cases he has seen where people with chronic, serious medical issues have been and continue to be helped by marijuana. He noted that marijuana does not have the dangerous side effects that many prescription medications do and that it is actually safer than many drugs being prescribed today. Dr. Gupta said in the program that there is not one documented case where death was due to marijuana overdose and he is right.

But as with any systematic paradigm shift, there will always be those whose minds are closed to change. So as the march toward legalization continues, there is new anti-legalization propaganda being written and spread through mainstream and social media. There have been multiple reports out of Colorado that there are now deaths attributed to marijuana overdose. Some say children were involved which automatically evokes feelings of fear in parents across the country. But when I tried to find more reliable sources to verify these articles, none existed. The AP reported on April 2 that a Wyoming college student jumped to his death in Colorado after eating a marijuana cookie while on Spring Break in Colorado. The autopsy listed marijuana intoxication as a “significant contributing factor” in the teen’s death. (Gurman)

Like alcohol, Colorado bans the sale of marijuana and marijuana edibles to people under the age of 21. But much like alcohol, teens that want to get it will always find a way. This young man was just 19, and his death has been ruled accidental. While it is true his death is tragic, is it a reason to reverse the course with marijuana? If you believe this is the case then you must consider the real dangers posed by alcohol. Many people who would like to see marijuana legalized say that it is much safer than the legal drug alcohol. Based solely on the numbers of hospitalizations and deaths, especially with young people, they would be right.

According to an article posted on Forbes.com in March of this year, “1,825 college students between the ages of 18 and 24 die each school year from alcohol-related unintentional injuries.” The author, Dr. Robert Glatter, MD attributes these deaths to one of the leading health risks facing our young people, and that is binge drinking. This number is quite small in comparison to emergency room visits and hospitalizations of young people that are a direct result of alcohol use.

Taking the most heat are the marijuana edibles that are now for sale in states where marijuana has become legal. The concern is that children are eating marijuana laced candy and baked goods and becoming ill. This would seem to be confirmed by an article in USA Today that reported that calls to the Rocky Mountain Poison Control is Colorado regarding marijuana ingestion in children had risen to 70 cases last year. While they admitted that this number was low, it was the rapid rise from years previous that caused concern. To put this in perspective, there are approximately 1.4 million pediatric poisonings each year involving prescription medications not including marijuana. (Henry, et.al) That is an average of approximately 28,000 calls per state. Tragically several hundreds of these cases result in deaths of these children, with the highest rates of death involving narcotics, sedatives and anti-depressants. (Henry, et.al.)

Of those 70 cases reported in Colorado involving marijuana, none resulted in death. The results are quite clear marijuana is as safe as prescription drugs are dangerous. For those who want to weigh in on the marijuana legalization debate, it is important to do your research, look at the big picture and put everything in perspective. Alcohol is legal and heavily regulated, yet its use is linked to thousands of deaths each year. Prescription drugs are legal and heavily regulated, yet they too are linked to thousands of deaths each year. Marijuana, on the other hand, is not legal and not available in much of the country, and thus far has not caused one death from overdose ever.

Additionally, research is showing marijuana has promise in treating many diseases more effectively and safely than dangerous prescription medications being used today. From cancer to epilepsy to depression and anxiety, to chronic autoimmune diseases, scientists are just scratching the surface when it comes to the potential life-changing and perhaps even, life-saving uses for marijuana.

References:

Drug Overdose in the United States: Fact Sheet. (2014, February 10). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 4, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/overdose/facts.html

Glatter, R. (2014, March 11). Spring Break’s Greatest Danger. Forbes. Retrieved May 5, 2014, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/robertglatter/2014/03/11/spring-breaks-greatest-danger/

Gurman, S. (2014, April 2). Young man leaps to death after eating pot-laced cookie. USA Today. Retrieved May 5, 2014, from http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/04/02/marijuana-pot-edible-death-colorado-denver/7220685/

Henry, K., & Harris, C. R. (2006). Deadly Ingestions. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 53(2), 293-315.

Hughes, T. (2014, April 2). Colo. Kids getting into parents’ pot-laced goodies. USA Today. Retrieved May 5, 2014 from http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/04/02/marijuana-pot-edibles-colorado/7154651/

A recent meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy of acupuncture for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and arrived at bizarrely positive conclusions.

The authors state that they searched 4 electronic databases for double-blind, placebo-controlled trials investigating the efficacy of acupuncture in the management of IBS. Studies were screened for inclusion based on randomization, controls, and measurable outcomes reported.

Six RCTs were included in the meta-analysis, and 5 articles were of high quality. The pooled relative risk for clinical improvement with acupuncture was 1.75 (95%CI: 1.24-2.46, P = 0.001). Using two different statistical approaches, the authors confirmed the efficacy of acupuncture for treating IBS and concluded that acupuncture exhibits clinically and statistically significant control of IBS symptoms.

As IBS is a common and often difficult to treat condition, this would be great news! But is it true? We do not need to look far to find the embarrassing mistakes and – dare I say it? – lies on which this result was constructed.

The largest RCT included in this meta-analysis was neither placebo-controlled nor double blind; it was a pragmatic trial with the infamous ‘A+B versus B’ design. Here is the key part of its methods section: 116 patients were offered 10 weekly individualised acupuncture sessions plus usual care, 117 patients continued with usual care alone. Intriguingly, this was the ONLY one of the 6 RCTs with a significantly positive result!

The second largest study (as well as all the other trials) showed that acupuncture was no better than sham treatments. Here is the key quote from this trial: there was no statistically significant difference between acupuncture and sham acupuncture.

So, let me re-write the conclusions of this meta-analysis without spin, lies or hype: These results of this meta-analysis seem to indicate that:

- currently there are several RCTs testing whether acupuncture is an effective therapy for IBS,

- all the RCTs that adequately control for placebo-effects show no effectiveness of acupuncture,

- the only RCT that yields a positive result does not make any attempt to control for placebo-effects,

- this suggests that acupuncture is a placebo,

- it also demonstrates how misleading studies with the infamous ‘A+B versus B’ design can be,

- finally, this meta-analysis seems to be a prime example of scientific misconduct with the aim of creating a positive result out of data which are, in fact, negative.

Recently, I have been invited by the final year pharmacy students of the ‘SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ZURICH‘ to discuss alternative medicine with them. The aspect I was keen to debate was the issue of retail-pharmacists selling medicines which are unproven or even disproven. Using the example of homeopathic remedies, I asked them how many might, when working as retail-pharmacists, sell such products. About half of them admitted that they would do this. In real life, this figure is probably closer to 100%, and this discrepancy may well be a reflection of the idealism of the students, still largely untouched by the realities of retail-pharmacy.

In our discussions, we also explored the reasons why retail-pharmacists might offer unproven or disproven medicines like homeopathic remedies to their customers. The ethical codes of pharmacists across the world quite clearly prohibit this – but, during the discussions, we all realised that the moral high ground is not easily defended against the necessity of making a living. So, what are the possible motivations for pharmacists to sell bogus medicines?

One reason would be that they are convinced of their efficacy. Whenever I talk to pharmacists, I do not get the impression that many of them believe in homeopathy. During their training, they are taught the facts about homeopathy which clearly do not support the notion of efficacy. If some pharmacists nevertheless were convinced of the efficacy of homeopathy, they would obviously not be well informed and thus find themselves in conflict with their duty to practice according to the current best evidence. On reflection therefore, strong positive belief can probably be discarded as a prominent reason for pharmacists selling bogus medicines like homeopathic remedies.

Another common argument is the notion that, because patients want such products, pharmacists must offer them. When considering it, the tension between the ethical duties as a health care professional and the commercial pressures of a shop-keeper becomes painfully obvious. For a shop-keeper, it may be perfectly fine to offer all products which might customers want. For a heath care professional, however, this is not necessarily true. The ethical codes of pharmacists make it perfectly clear that the sale of unproven or disproven medicines is not ethical. Therefore, this often cited notion may well be what pharmacists feel, but it does not seem to be a valid excuse for selling bogus medicines.

A variation of this theme is the argument that, if patients were unable to buy homeopathic remedies for self-limiting conditions which do not really require treatment at all, they would only obtain more harmful drugs. The notion here is that it might be better to sell harmless homeopathic placebos in order to avoid the side-effects of real but non-indicated medicines. In my view, this argument does not hold water: if no (drug) treatment is indicated, professionals have a duty to explain this to their patients. In this sector of health care, a smaller evil cannot easily be justified by avoiding a bigger one; on the contrary, we should always thrive for the optimal course of action, and if this means reassurance that no medical treatment is needed, so be it.

An all too obvious reason for selling bogus medicines is the undeniable fact that pharmacists earn money by doing so. There clearly is a conflict of interest here, whether pharmacists want to admit it or not – and mostly they fail to do so or play down this motivation in their decision to sell bogus medicines.

Often I hear from pharmacists working in large chain pharmacies like Boots that they have no influence whatsoever over the range of products on sale. This perception mat well be true. But equally true is the fact that no health care professional can be forced to do things which violate their code of ethics. If Boots insists on selling bogus medicines, it is up to individual pharmacists and their professional organisations to change this situation by protesting against such unethical malpractice. In my view, the argument is therefore not convincing and certainly does not provide an excuse in the long-term.

While discussing with the Swiss pharmacy students, I was made aware of yet another reason for selling bogus medicines in pharmacies. Some pharmacists might feel that stocking such products provides an opportunity for talking to patients and informing them about the evidence related to the remedy they were about to buy. This might dissuade them from purchasing it and could persuade them to get something that is effective instead. In this case, the pharmacist would merely offer the bogus medicine in order to advise customers against employing it. This strategy might well be an ethical way out of the dilemma; however, I doubt that this strategy is common practice with many pharmacists today.

With all this, we should keep in mind that there are many shades of grey between the black and white of the two extreme attitudes towards bogus medicines. There is clearly a difference whether pharmacists actively encourage their customers to buy bogus treatments (in the way it often happens in France, for instance), or whether they merely stock such products and, where possible, offer responsible, evidence-based advise to people who are tempted to buy them.

At the end of the lively but fruitful discussion with the Swiss students I felt optimistic: perhaps the days when pharmacists were the snake-oil salesmen of the modern era are counted?

There is much debate about the usefulness of chiropractic. Specifically, many people doubt that their chiropractic spinal manipulations generate more good than harm, particularly for conditions which are not related to the spine. But do chiropractors treat such conditions frequently and, if yes, what techniques do they employ?

This investigation was aimed at describing the clinical practices of chiropractors in Victoria, Australia. It was a cross-sectional survey of 180 chiropractors in active clinical practice in Victoria who had been randomly selected from the list of 1298 chiropractors registered on Chiropractors Registration Board of Victoria. Twenty-four chiropractors were ineligible, 72 agreed to participate, and 52 completed the study.

Each participating chiropractor documented encounters with up to 100 consecutive patients. For each chiropractor-patient encounter, information collected included patient health profile, patient reasons for encounter, problems and diagnoses, and chiropractic care.

Data were collected on 4464 chiropractor-patient encounters between 11 December 2010 and 28 September 2012. In most (71%) cases, patients were aged 25-64 years; 1% of encounters were with infants. Musculoskeletal reasons for the consultation were described by patients at a rate of 60 per 100 encounters, while maintenance and wellness or check-up reasons were described at a rate of 39 per 100 encounters. Back problems were managed at a rate of 62 per 100 encounters.

The most frequent care provided by the chiropractors was spinal manipulative therapy and massage. The table shows the precise conditions treated

Distribution of problems managed (20 most frequent problems), as reported by chiropractors

| Problem group | No. (%) of recorded diagnoses* (n = 5985) | Rate per 100 encounters (n = 4417) | 95% CI | ICC |

| Back problem | 2757 (46.07%) | 62.42 | (55.24–70.53) | 0.312 |

| Neck problem | 683 (11.41%) | 15.46 | (11.23–21.30) | 0.233 |

| Muscle problem | 434 (7.25%) | 9.83 | (6.64–14.55) | 0.207 |

| Health maintenance or preventive care | 254 (4.24%) | 5.75 | (3.24–10.22) | 0.251 |

| Back syndrome with radiating pain | 215 (3.59%) | 4.87 | (2.91–8.14) | 0.165 |

| Musculoskeletal symptom or complaint, or other | 219 (3.66%) | 4.96 | (2.39–10.28) | 0.350 |

| Headache | 179 (2.99%) | 4.05 | (2.87–5.71) | 0.053 |

| Sprain or strain of joint | 167 (2.79%) | 3.78 | (2.30–6.22) | 0.115 |

| Shoulder problem | 87 (1.45%) | 1.97 | (1.37–2.83) | 0.022 |

| Nerve-related problem | 62 (1.04%) | 1.40 | (0.72–2.75) | 0.072 |

| General symptom or complaint, other | 51 (0.85%) | 1.15 | (0.22–6.06) | 0.407 |

| Bursitis, tendinitis or synovitis | 47 (0.79%) | 1.06 | (0.71–1.60) | 0.011 |

| Kyphosis and scoliosis | 47 (0.79%) | 1.06 | (0.65–1.75) | 0.023 |

| Foot or toe symptom or complaint | 48 (0.80%) | 1.09 | (0.41–2.87) | 0.123 |

| Ankle problem | 46 (0.77%) | 1.04 | (0.40–2.69) | 0.112 |

| Osteoarthrosis, other (not spine) | 39 (0.65%) | 0.88 | (0.51–1.53) | 0.023 |

| Hip symptom or complaint | 35 (0.58%) | 0.79 | (0.53–1.19) | 0.006 |

| Leg or thigh symptom or complaint | 35 (0.58%) | 0.79 | (0.49–1.28) | 0.012 |

| Musculoskeletal injury | 33 (0.55%) | 0.75 | (0.45–1.24) | 0.013 |

| Depression | 29 (0.48%) | 0.66 | (0.10–4.23) | 0.288 |

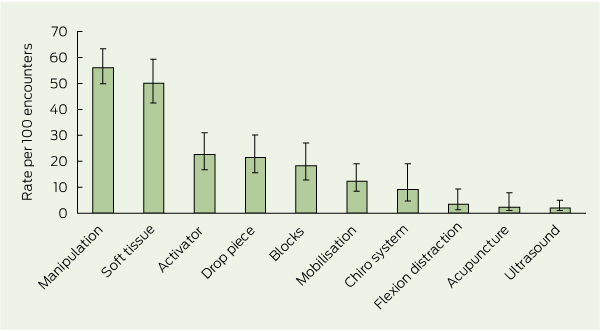

These findings are impressive in that they suggest that most Australian chiropractors treat non-spinal conditions for which there is no evidence that the most frequently used interventions are effective. The treatments employed are depicted in this graph:

Distribution of techniques and care provided by chiropractors, with 95% CI

[Activator = hand-held spring-loaded device that delivers an impulse to the spine. Drop piece = chiropractic treatment table with a segmented drop system which quickly lowers the section of the patient’s body corresponding with the spinal region being treated. Blocks = wedge-shaped blocks placed under the pelvis.

Chiro system = chiropractic system of care, eg, Applied Kinesiology, Sacro-Occipital Technique, Neuroemotional Technique. Flexion distraction = chiropractic treatment table that flexes in the middle to provide traction and mobilisation to the lumbar spine.]

There is no good evidence I know of demonstrating these techniques to be effective for the majority of the conditions listed in the above table.

A similar bone of contention is the frequent use of ‘maintenance’ and ‘wellness’ care. The authors of the article comment: The common use of maintenance and wellness-related terms reflects current debate in the chiropractic profession. “Chiropractic wellness care” is considered by an indeterminate proportion of the profession as an integral part of chiropractic practice, with the belief that regular chiropractic care may have value in maintaining and promoting health, as well as preventing disease. The definition of wellness chiropractic care is controversial, with some chiropractors promoting only spine care as a form of wellness, and others promoting evidence-based health promotion, eg, smoking cessation and weight reduction, alongside spine care. A 2011 consensus process in the chiropractic profession in the United States emphasised that wellness practice must include health promotion and education, and active strategies to foster positive changes in health behaviours. My own systematic review of regular chiropractic care, however, shows that the claimed effects are totally unproven.

One does not need to be overly critical to conclude from all this that the chiropractors surveyed in this investigation earn their daily bread mostly by being economical with the truth regarding the lack of evidence for their actions.

It is almost 10 years ago that Prof Kathy Sykes’ BBC series entitled ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE was aired. I had been hired by the BBC as their advisor for the programme and had tried my best to iron out the many mistakes that were about to be broadcast. But the scope for corrections turned out to be narrow and, at one stage, the errors seemed too serious and too far beyond repair to continue with my task. I had thus offered my resignation from this post. Fortunately this move led to some of my concerns being addressed after all, and they convinced me to remain in post.

The first part of the series was on acupuncture, and Kathy presented the opening scene of a young women undergoing open heart surgery with the aid of acupuncture. All the BBC had ever shown me and asked me to advise on was the text – I had never seen the images. Kathy’s text included the statement that the patient was having the surgery “with only needles to control the pain.” I had not objected to this statement in the firm belief that the images of the film would back up this extraordinary claim. As it turned out, it did not; the patient clearly had all sorts of other treatments given through intra-venous lines and, in the film, these were openly in the view of Kathy Sykes.

This overt contradiction annoyed not just me but several other people as well. One of them was Simon Singh who filed an official complaint against the BBC for misleading the public, and eventually won his case.

The notion that acupuncture can serve as an alternative to anaesthesia or other surgical conditions crops up with amazing regularity. It is important not least because is often used as a promotional tool with the implication that, IF ACUPUNCTURE CAN ACHIVE SUCH DRAMATIC EFFECTS, IT MUST BE AN INCREDIBLY USEFUL TREATMENT! It is therefore relevant to ask what the scientific evidence tells us about this issue.

This was the question we wanted to address in a recent publication. Specifically, our aim was to summarise recent systematic reviews of acupuncture for surgical conditions.

Thirteen electronic databases were searched for relevant reviews published since 2000. Data were extracted by two independent reviewers according to predefined criteria. Twelve systematic reviews met our inclusion criteria. They related to the prevention or treatment of post-operative nausea and vomiting as well as to surgical or post-operative pain. The reviews drew conclusions which were far from uniform; specifically for surgical pain the evidence was not convincing. We concluded that “the evidence is insufficient to suggest that acupuncture is an effective intervention in surgical settings.”

So, Kathy Sykes’ comment was misguided in more than just one way: firstly, the scene she described in the film did not support what she was saying; secondly, the scientific evidence fails to support the notion that acupuncture can be used as an alternative to analgesia during surgery.

This story has several positive outcomes all the same. After seeing the BBC programme, Simon Singh contacted me to learn my views on the matter. This prompted me to support his complaint against the BBC and helped him to win this case. Furthermore, it led to a co-operation and friendship which produced our book TRICK OR TREATMENT.

These days, there is so much hype about alternative cancer treatments that it is hard to find a cancer patient who is not tempted to try this or that alternative medicine. Often it is employed without the knowledge of the oncology team, solely on the advice of non-medically qualified practitioners (NMPs). But is that wise? The aim of this survey was to find out.

Members of several German NMP-associations were invited to complete an online questionnaire. The questionnaire explored areas such as the diagnosis and treatment, goals for using complementary/alternative medicine (CAM), communication with the oncologist, and sources of information.

Of a total of 1,500 members of the NMP associations, 299 took part in this survey. The results show that the treatments employed by NMPs were heterogeneous. Homeopathy was used by 45% of the NMPs, and 10% believed it to be a treatment directly against cancer. Herbal therapy, vitamins, orthomolecular medicine, ordinal therapy, mistletoe preparations, acupuncture, and cancer diets were used by more than 10% of the NMPs. None of the treatments were discussed with the respective physician on a regular basis.

The authors concluded from these findings that many therapies provided by NMPs are biologically based and therefore may interfere with conventional cancer therapy. Thus, patients are at risk of interactions, especially as most NMPs do not adjust their therapies to those of the oncologist. Moreover, risks may arise from these CAM methods as NMPs partly believe them to be useful anticancer treatments. This may lead to the delay or even omission of effective therapies.

Anyone faced with a diagnosis of CANCER is understandably keen to leave no stone unturned to bring about a cure of the disease. Many patients thus go on to the Internet and look what alternative options are on offer. There they find virtually millions of sites advertising thousands of bogus cancer ‘cures’. Others consult their alternative practitioners and seek help. This new survey shows yet again that the advice they receive is dangerous. In fact, it might well be even more dangerous than the results imply: the response rate of the survey was dismal, and I fear that the less responsible NMPs tended not to reply.

None of the treatments listed above can cure cancer. For instance, homeopathy, the most popular alternative cancer treatment in Germany, will have no effect whatsoever on the natural history of the disease. To claim otherwise is criminally irresponsible.

But far too many patients are unaware of the evidence and of the dangers of being misled by bogus claims. What we need, I think, is a major campaign to get the word out. It would be a campaign that saves lives!