Homeopathy works!

At least this is what the authors of this new study want us to believe.

But are they right?

This RCT is entitled ‘Efficacy and tolerability of a complex homeopathic drug in children suffering from dry cough-A double-blind, placebo- controlled, clinical trial’. It recruited children suffering from acute dry cough to assess the efficacy and tolerability of a complex homeopathic remedy in liquid form (Drosera, Coccus cacti, Cuprum Sulfuricum, Ipecacuanha = Monapax syrup, short: verum).

The authors stated that “preparations of Drosera, Coccus cacti, Cuprum sulfuricum, and Ipecacuanha are well-known antitussives in homeopathic medicine. Each of them is connected with special subtypes of cough. Drosera is intended for inflammations of the respiratory tract, especially for whooping cough. Coccus cacti is intended for inflammations of the nasopharyngeal space and the respiratory tract. Cuprum sulfuricum is intended for spasmodic coughing at night. Ipecacuanha is intended for bronchitis, bronchial asthma, and whooping cough. The complex homeopathic drug explored in this trial consists of all four of these active substances.”

According to the authors of the paper, “the primary objective of the trial was to demonstrate the superiority of verum compared to the placebo”.

A total of 89 children, enrolled in the Ukraine between 15/04/2008 and 26/05/2008 in 9 trial centres, received verum and 91 received placebo daily for 7 days (age groups 0.5–3, 4–7 and 8–12 years). The trial was conducted using an adaptive 3-stage group sequential design with possible sample size adjustments after the two planned interim analyses. The inverse normal method of combining the p-values from all three stages was used for confirmatory hypothesis testing at the interim analyses as well as at the final analysis. The primary efficacy variable was the improvement of the Cough Assessment Score. Tolerability and compliance were also assessed. A confirmatory statistical analysis was performed for the primary efficacy variable and a descriptive analysis for the secondary parameters.

A total of 180 patients (89 in the verum and 91 in the placebo group) evaluable according to the intention-to-treat principle were included in the trial. The Cough Assessment Score showed an improvement of 5.2 ± 2.6 points for children treated with verum and 3.2 ± 2.6 points in the placebo group (p < 0.0001). The difference of the least square means of the improvements was 1.9 ± 0.4. The effect size of Cohen´s d was d = 0.77. In all secondary parameters the patients in the verum group showed higher rates of improvement and remission than those in the placebo group. In 15 patients (verum: n = 6; placebo: n = 9) 18 adverse drug reactions of mild or moderate intensity were observed.

The authors concluded that the administering verum resulted in a statistically significantly greater improvement of the Cough Assessment Score than the placebo. The tolerability was good and not inferior to that of the placebo.

This study seems fairly rigorous. What is more, it has been published in a mainstream journal of reasonably high standing. So, how can its results be positive? We all know that homeopathy does not work, don’t we?

Are we perhaps mistaken?

Are highly diluted homeopathic remedies effective after all?

I don’t think so.

Let me explain to you a few points that raise my suspicions about this study:

- It was conducted 10 years ago; why did it take that long to get it published?

- I don’t think highly of a study with “the primary objective … to demonstrate the superiority” of the experimental interventions. Scientists use RCTs for testing efficacy and pseudo-scientist use it for demonstrating it, I think.

- The study was conducted in the Ukraine in 9 centres, yet no Ukrainian is an author of the paper, and there is not even an acknowledgement of these primary investigators.

- The ‘adaptive 3-stage group sequential design with possible sample size adjustments’ sounds very odd to me, but I may be wrong; I am not a statistician.

- We learn that 180 patients were evaluated, but not how many were entered into the trial?

- The Cough Assessment Score is not a validated outcome measure.

- Was the verum distinguishable from the placebo? It would be easy to test whether the patients/parents were truly blinded. Yet no such results were included.

- The trial was funded by the manufacturer of the homeopathic remedy.

- The paper has three authors 1)Hans W. Voß has no conflict of interest to declare. 2) Rainer Brünjes is employed at Cassella-med, the marketing authorisation holder of the study product. 3) Andreas Michalsen has consulted for Cassella-med and participated in advisory boards.

I know, homeopathy fans will think I am nit-picking; and perhaps they are correct. So, let me tell you why I really do strongly reject the notion that this study shows or even suggests that highly diluted homeopathic remedies are more than placebos.

The remedy used in this study is composed of Drosera 0,02 g, Hedera helix Ø 0,04 g, China D1 0,02 g, Coccus cacti D1 0,04 g, Cuprum sulfuricum D4 2,0 g, Ipecacuanha D4 2,0 g, Hyoscyamus D4 2,0 g.

In case you don’t know what ‘Ø’ stands for (I don’t blame you, hardly anyone outside the world of homeopathy does), it signifies a ‘mother tincture’, i. e. an undiluted herbal extract; and ‘D1’ signifies diluted 1:10. This means that the remedy may be homeopathic from a regulatory point of view, but for all intents and purposes it is a herbal medicine. It contains an uncounted amount of active compounds, and it is therefore hardly surprising that it might have pharmacological effects. In turn, this means that this trial does by no means overturn the fact that highly diluted homeopathic remedies are pure placebos.

It’s a pity, I find, that the authors of the paper fail to explain this simple fact in full detail – might one think that they intentionally aimed at misleading us?

We all know that there is a plethora of interventions for and specialists in low back pain (chiropractors, osteopaths, massage therapists, physiotherapists etc., etc.); and, depending whether you are an optimist or a pessimist, each of these therapies is as good or as useless as the next. Today, a widely-publicised series of articles in the Lancet confirms that none of the current options is optimal:

Almost everyone will have low back pain at some point in their lives. It can affect anyone at any age, and it is increasing—disability due to back pain has risen by more than 50% since 1990. Low back pain is becoming more prevalent in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) much more rapidly than in high-income countries. The cause is not always clear, apart from in people with, for example, malignant disease, spinal malformations, or spinal injury. Treatment varies widely around the world, from bed rest, mainly in LMICs, to surgery and the use of dangerous drugs such as opioids, usually in high-income countries.

The Lancet publishes three papers on low back pain, by an international group of authors led by Prof Rachelle Buchbinder, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, which address the issues around the disorder and call for worldwide recognition of the disability associated with the disorder and the removal of harmful practices. In the first paper, Jan Hartvigsen, Mark Hancock, and colleagues draw our attention to the complexity of the condition and the contributors to it, such as psychological, social, and biophysical factors, and especially to the problems faced by LMICs. In the second paper, Nadine Foster, Christopher Maher, and their colleagues outline recommendations for treatment and the scarcity of research into prevention of low back pain. The last paper is a call for action by Rachelle Buchbinder and her colleagues. They say that persistence of disability associated with low back pain needs to be recognised and that it cannot be separated from social and economic factors and personal and cultural beliefs about back pain.

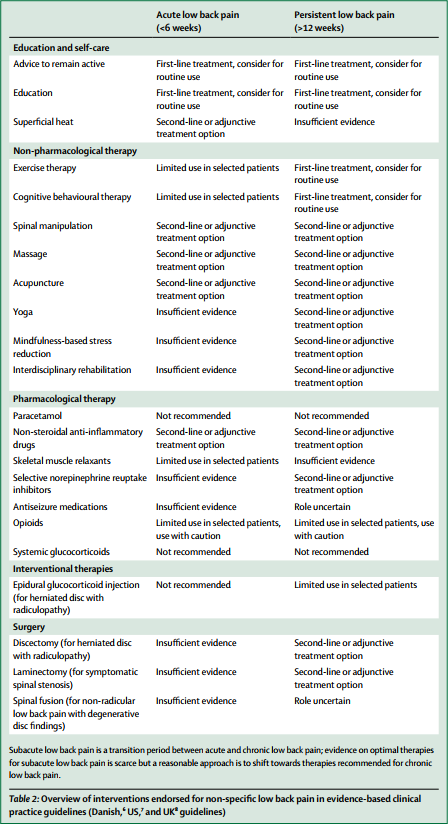

Overview of interventions endorsed for non-specific low back pain in evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (Danish, US, and UK guidelines)

In this situation, it makes sense, I think, to opt for a treatment (amongst similarly effective/ineffective therapies) that is at least safe, cheap and readily available. This automatically rules out chiropractic, osteopathy and many others. Exercise, however, does come to mind – but what type of exercise?

The aim of this meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials was to gain insight into the effectiveness of walking intervention on pain, disability, and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain (LBP) at post intervention and follow ups.

Six electronic databases (PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, Scopus, PEDro and The Cochrane library) were searched from 1980 to October 2017. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with chronic LBP were included, if they compared the effects of walking intervention to non-pharmacological interventions. Pain, disability, and quality of life were the primary health outcomes.

Nine RCTs were suitable for meta-analysis. Data was analysed according to the duration of follow-up (short-term, < 3 months; intermediate-term, between 3 and 12 months; long-term, > 12 months). Low- to moderate-quality evidence suggests that walking intervention in patients with chronic LBP was as effective as other non-pharmacological interventions on pain and disability reduction in both short- and intermediate-term follow ups.

The authors concluded that, unless supplementary high-quality studies provide different evidence, walking, which is easy to perform and highly accessible, can be recommended in the management of chronic LBP to reduce pain and disability.

I know – this will hardly please the legions of therapists who earn their daily bread with pretending their therapy is the best for LBP. But healthcare is clearly not about the welfare of the therapists, it is/should be about patients. And patients should surely welcome this evidence. I know, walking is not always easy for people with severe LBP, but it seems effective and it is safe, free and available to everyone.

My advice to patients is therefore to walk (slowly and cautiously) to the office of their preferred therapist, have a little rest there (say hello to the staff perhaps) and then walk straight back home.

by Norbert Aust as ‘guest blogger’ and Edzard Ernst

Professor Frass has repeatedly stated that his published criticism of the Lancet meta-analysis has never been refuted, and therefore homeopathy is a valid therapy. The last time we heard him say this was during a TV discussion (March 2018) where he said that, if one succeeded in scientifically refuting the arguments set out in his paper, one would show the ineffectiveness of homeopathy.

In today’s post, we quote the paper Frass refers to, published as a ‘letter to the editor’ (published in the journal Homeopathy) by Frass et al (bold typing), and provide our rebuttal (in normal print) of it:

Even with careful selection, it remains problematic to compare studies of a pool of 165 for homeopathy vs 4200,000 for conventional medicine. This factor of 41000 already contains asymmetry.

We see no good reasons why the asymmetry poses a problem; it does not conceivably impact on the outcome, nor does it bias the results. In fact, such asymmetries are common is research.

Furthermore, it appears that there is discrimination when publications in English (94/110, 85% in the conventional medicine group vs 58/110, 53% in the homeopathy group) are rated higher quality (Table 2).

We cannot confirm that the table demonstrates such a discrimination, nor do we understand how this would disadvantage homeopathy.

Neither the Summary nor the Introduction clearly specify the aim of the study.

The authors stated that they “analysed trials of homoeopathy and conventional medicine and estimated treatment effects in trials least likely to be affected by bias”. It is hardly difficult to transform this into their aim: the authors aimed at analysing trials of homoeopathy and conventional medicine and estimating treatment effects in trials least likely to be affected by bias.

Furthermore, the design of the study differs substantially from the final analysis and therefore the prolonged description of how the papers and databases were selected is misleading: instead of analysing all 110 studies retrieved by their defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, the authors reduce the number of investigated studies to ‘larger trials of higher quality’. By using these sub-samples, the results seem to differ between conventional medicine and homeopathy.

This statement discloses a misconception of the approach used in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis of all 110 trials found some advantages of homeopathy. When the authors performed a sensitivity analysis with high quality and larger studies, this advantage disappeared. The sensitivity analysis was to determine whether the overall treatment effect seen in the initial analysis was real or false-positive. In the case of homeopathy, it turned out to be false (and presumably for this reason, the authors hardly mention it in their paper), whereas for the trials of conventional medicines, it was real. This procedure is in keeping with the authors’ stated aims.

The meta-analysis does not compare studies of homeopathy vs studies of conventional medicine, but specific effects of these two methods in separate analyses. Therefore, a direct comparison must not be made from this study.

We fail to see the significance in terms of the research question stated by the authors. Even Frass et al use direct comparisons above.

However, there remains great uncertainty about the selection of the eight homeopathy and the six conventional medicine studies: the cut-off point seems to be arbitrarily chosen: if one looks at Figure 2, the data look very much the same for both groups. This holds true even if various levels of SE are considered. Therefore, the selection of larger trials of higher quality is a post-festum hypothesis but not a pre-set criterion.

This is not true, Shang et al clearly stated in their paper: “Trials with SE (standard error) in the lowest quartile were considered larger trials.” It is common, reasonable and in keeping with the authors’ aims to conduct sensitivity analyses using a subset of trials that seem more reliable than the average.

The question remains: was the restriction to larger trials of higher quality part of the original protocol or was this a data-driven decision? Since we cannot find this proposed reduction in the abstract, we doubt that it was included a priori.

We are puzzled by this statement and fail to understand why Frass et al insist that this information should have been in the abstract.

However, even if one assumes that this was a predefined selection, there are still some problems with the authors’ interpretation: for larger trials of higher reported methodological quality, the odds ratio was 0.88 (CI 95%: 0.65–1.19) based on eight trials of homeopathy: although this finding does not prove an effect of the study design on the 5% level, neither does it disprove the hypothesis that the results might have been achieved by homeopathy. For conventional medicine, the odds ratio was 0.58 (CI 95% 0.39–0.85), which indicates that the results may not be explained by mere chance with a 5% uncertainty.

As the outcome failed to reach the level of significance, the null-hypothesis (“there is no difference”) cannot be discarded, and this is sufficient evidence to show that there is no evidence for the effectiveness of homeopathy. The comment by Frass et al seems to be based on a misunderstanding how science operates.

Although the authors acknowledge that ‘to prove a negative is impossible’ the authors clearly favour the view that there is evidence that homoeopathy exhibits no effect beyond the placebo-effect. However, this conclusion was drawn after a substantial modification of the original protocol which considerably weakens its validity from the methodological point of view. After acquiring the trials by their original inclusion- and exclusion criteria they introduced a further criterion, ‘larger trials of higher reported methodological quality’. Thus, eight trials (=46% of the larger trials) in the homoeopathy group were left and only six (32%) in conventional medicine group (an odds ratio of 0.75 in favour of homoeopathy).

As explained above, the authors’ reasoning was clear and rational; it did not follow the logic suggested by Frass et al. which confirms our suspicion already mentioned above that Frass et al misunderstood the concept of the Shang meta-analysis.

But the decisive point is that it is unlikely that these six trials are still matched to the eight samples of homoeopathy (although each of the 110 in the original was matched). Consequently, one cannot conclude that these trials are still comparable. Thus, any comparisons of results between them are unjustified.

Further evidence that Frass et al misunderstood the concept of the Shang meta-analysis.

The rationale for this major alteration of the study protocol was the assumption, that these larger, higher quality trials are not biased, but no evidence or databased justification is given. Neither the actual data (odds ratio, matching parameters…) nor a funnel plot (to indicate that there is no bias) of the final 14 trials are supplied although these parameters constitute the ground of their conclusion.

Further evidence that Frass et al misunderstood the concept of the Shang meta-analysis.

The other 206 trials (94% of the originally selected according to the protocol) were discarded because of possible publication biases as visualized by the funnel plots. However, the use of funnel plots is also questionable. Funnel plots are thought to detect publication bias, and heterogeneity to detect fundamental differences between studies.

Further evidence that Frass et al misunderstood the concept of the Shang meta-analysis.

New evidence suggests that both of these common beliefs are badly flawed. Using 198 published meta-analyses, Tang and Liu demonstrate that the shape of a funnel plot is largely determined by the arbitrary choice of the method to construct the plot. When a different definition of precision and/or effect measure was used, the conclusion about the shape of the plot was altered in 37 (86%) of the 43 meta-analyses with an asymmetrical plot suggesting selection bias. In the absence of a consensus on how the plot should be constructed, asymmetrical funnel plots should be interpreted cautiously.

Further evidence that Frass et al misunderstood the concept of the Shang meta-analysis.

These findings also suggest that the discrepancies between large trials and corresponding meta-analyses and heterogeneity in metaanalyses may also be determined by how they are evaluated. Researchers tend to read asymmetric funnel plots as evidence of publication bias, even though metaanalyses without publication bias frequently have asymmetric plots and meta-analysis with publication bias frequently have symmetric plots, simply due to chance.

Perhaps we should mention that the senior author of the Lancet meta-analysis, Mathias Egger, is the clinical epidemiologist who invented the funnel plot and certainly knows how to use and interpret it.

Use of funnel plots is even more unreliable when there is heterogeneity. Apart from the questionable selection of the samples there is a further aspect of randomness which further weakens their conclusion: the odds ratio of the eight trials of homoeopathy was 0.88 (CI 0.65–1.19), which might be significant around the 7–8% level. Actually, the reader might be interested to know at which exact level homeopathy would have become significant. Thus, there is no support of their conclusion any more when you shift the level of significance by mere, say 2–3%.

What number of grains is required to build a heap? Certainly there is such a limit. Five grains are not a heap, five billion are. But if you select any specific value, you will find it hard to explain if one grain less changes the characteristic of a heap to become a number of grains only. Same here. If p = 0.05 is the limit of significance, p = 0.05001 is not significant, let alone, when p is 2-3%higher than that.

In addition, with such controversial hypotheses the scientific community would tend to use a level of significance of 1% in which case the odds ratio of the conventional studies would not be significant either.

The level of 5% is commonly applied in medical research; it is the accepted standard. Frass et al also apply it in their studies; but here they want to change it. Why, to suit their preconceived ideas?

From a statistical point of view, the power of the test, considering the small sample sizes, should have been stated, especially in the case of a nonsignificant result.

This might have been informative but is rarely done in meta-analyses.

Above all, the choice of which trials are to be evaluated is crucial. By choosing a different sample of eight trials (eg the eight trials in ‘acute infections of the upper respiratory tract’, as mentioned in the Discussion section) a radically different conclusion would have had to be drawn (namely a substantial beneficial effect of homeopathy—as the authors state).

Further evidence that Frass et al misunderstood the concept of the Shang meta-analysis.

The authors may not be aware that larger trials are usually not ‘classical’ homeopathic interventions, because the main principle of homeopathy, individualization are difficult to apply in large trials. In this respect, the whole study lacks sound understanding of what homeopathy really is.

This is a red herring; firstly the authors did not aim to evaluate individualised homeopathy. Secondly, Frass et al know very well that clinical homeopathy is not individualised and regarded as entirely legitimate by homeopaths. And finally, the largest trial of individualised homeopathy included in Mathie’s review of individualized homeopathy had 251 participants.

So, why has so far no rebuttal of this ‘letter to the Editor’ been published? We suspect that the journal Homeopathy has little incentive to publish a critical response, and critics of homeopathy have even less motivation to submit one to this journal. Other journals have no reason at all to pursue a discussion started in ‘Homeopathy’. In other words, Frass et al were safe from any rebuttal – until today, that is.

“In my medical practice, writes Sheila Patel, M.D. on the website of Deepak Chopra, I always take into consideration the underlying dosha of a patient, or what their main imbalance is, when choosing treatments out of the many options available. For example, if I see someone who has the symptoms of hypertension as well as a Kapha imbalance, I may prescribe a diuretic, since excess water is more likely to be a contributing factor. I would also encourage more exercise or physical activity, since lack of movement is often a causative factor for these individuals. However, in a Vata-type person with hypertension, a diuretic may actually cause harm, as the Vata system tends to have too much dryness (air and space). I’ve observed that Vatas often have more side effects and electrolyte imbalances due to the diuretic medication. For these individuals, a beta-blocker may be a better choice, as this “slows” down the excitatory pathways in the body. In addition, I recommend meditation and calming activities to settle the excess energy as an adjunct to (or at times, instead of) the medicine. Alternatively, for someone with hypertension who is predominantly a Pitta type or who has a Pitta imbalance, I may choose a calcium-channel blocker, as this medication may be more beneficial in regulating the process of “energy exchange” in the body, which is represented by the fire element of Pitta. This is just one example of the way in which we can tailor our choice of medication to best suit the individual.

“In contrast with conventional medicine, which until very recently has assumed that a given disorder or disease is the same in all people, Ayurveda places great importance on recognizing the unique qualities of individual human beings. Ayurveda’s understanding of constitutional types or doshas offers us a remarkably accurate way to pinpoint what is happening inside each individual, allowing us to customize treatment and offer specific lifestyle recommendations to prevent disease and promote health and longevity. Keeping the doshas balanced is one of the most important factors in keeping the whole mind-body system in balance. When our mind-body system is in balance and we are connecting to our inner wisdom and intelligence, then we are most able to realize our full human potential and achieve our optimal state of being…”

END OF QUOTE

From such texts, some might conclude that Ayurvedic medicine is gentle and kind (personally, I am much more inclined to feel that Ayurvedic medicine is full of BS). This may be true or not, but Ayurvedic medicines are certainly anything but gentle and kind. In fact, they can be positively dangerous. I have repeatedly blogged about their risks, in particular the risk of heavy metal poisoning (see here, here, and here, for instance).

My 2002 systematic review summarised the evidence available at the time and concluded that heavy metals, particularly lead, have been a regular constituent of traditional Indian remedies. This has repeatedly caused serious harm to patients taking such remedies. The incidence of heavy metal contamination is not known, but one study shows that 64% of samples collected in India contained significant amounts of lead (64% mercury, 41% arsenic and 9% cadmium). These findings should alert us to the possibility of heavy metal content in traditional Indian remedies and motivate us to consider means of protecting consumers from such risks.

Meanwhile, new data have emerged and a new article with important information has recently been published by authors from the Department of Occupational and Environmental Health , College of Public Health, The University of Iowa and the State Hygienic Laboratory at the University of Iowa, USA. They present an analysis based on reports of toxic metals content of Ayurvedic products obtained during an investigation of lead poisoning among users of Ayurvedic medicine. Samples of Ayurvedic formulations were analysed for metals and metalloids following established US. Environmental Protection Agency methods. Lead was found in 65% of 252 Ayurvedic medicine samples with mercury and arsenic found in 38 and 32% of samples, respectively. Almost half of samples containing mercury, 36% of samples containing lead, and 39% of samples containing arsenic had concentrations of those metals per pill that exceeded, up to several thousand times, the recommended daily intake values for pharmaceutical impurities.

The authors concluded that lack of regulations regarding manufacturing and content or purity of Ayurvedic and other herbal formulations poses a significant global public health problem.

I could not have said it better myself!

As I often said, I find it regrettable that sceptics often say THERE IS NOT A SINGLE STUDY THAT SHOWS HOMEOPATHY TO BE EFFECTIVE (or something to that extent). This is quite simply not true, and it gives homeopathy-fans the occasion to suggest sceptics wrong. The truth is that THE TOTALITY OF THE MOST RELIABLE EVIDENCE FAILS TO SUGGEST THAT HIGHLY DILUTED HOMEOPATHIC REMEDIES ARE EFFECTIVE BEYOND PLACEBO. As a message for consumers, this is a little more complex, but I believe that it’s worth being well-informed and truthful.

And that also means admitting that a few apparently rigorous trials of homeopathy exist and some of them show positive results. Today, I want to focus on this small set of studies.

How can a rigorous trial of a highly diluted homeopathic remedy yield a positive result? As far as I can see, there are several possibilities:

- Homeopathy does work after all, and we have not fully understood the laws of physics, chemistry etc. Homeopaths favour this option, of course, but I find it extremely unlikely, and most rational thinkers would discard this possibility outright. It is not that we don’t quite understand homeopathy’s mechanism; the fact is that we understand that there cannot be a mechanism that is in line with the laws of nature.

- The trial in question is the victim of some undetected error.

- The result has come about by chance. Of 100 trials, 5 would produce a positive result at the 5% probability level purely by chance.

- The researchers have cheated.

When we critically assess any given trial, we attempt, in a way, to determine which of the 4 solutions apply. But unfortunately we always have to contend with what the authors of the trial tell us. Publications never provide all the details we need for this purpose, and we are often left speculating which of the explanations might apply. Whatever it is, we assume the result is false-positive.

Naturally, this assumption is hard to accept for homeopaths; they merely conclude that we are biased against homeopathy and conclude that, however, rigorous a study of homeopathy is, sceptics will not accept its result, if it turns out to be positive.

But there might be a way to settle the argument and get some more objective verdict, I think. We only need to remind ourselves of a crucially important principle in all science: INDEPENDENT REPLICATION. To be convincing, a scientific paper needs to provide evidence that the results are reproducible. In medicine, it unquestionably is wise to accept a new finding only after it has been confirmed by other, independent researchers. Only if we have at least one (better several) independent replications, can we be reasonably sure that the result in question is true and not false-positive due to bias, chance, error or fraud.

And this is, I believe, the extremely odd phenomenon about the ‘positive’ and apparently rigorous studies of homeopathic remedies. Let’s look at the recent meta-analysis of Mathie et al. The authors found several studies that were both positive and fairly rigorous. These trials differ in many respects (e. g. remedies used, conditions treated) but they have, as far as I can see, one important feature in common: THEY HAVE NOT BEEN INDEPENDENTLY REPLICATED.

If that is not astounding, I don’t know what is!

Think of it: faced with a finding that flies in the face of science and would, if true, revolutionise much of medicine, scientists should jump with excitement. Yet, in reality, nobody seems to take the trouble to check whether it is the truth or an error.

To explain this absurdity more fully, let’s take just one of these trials as an example, one related to a common and serious condition: COPD

The study is by Prof Frass and was published in 2005 – surely long enough ago for plenty of independent replications to emerge. Its results showed that potentized (C30) potassium dichromate decreases the amount of tracheal secretions was reduced, extubation could be performed significantly earlier, and the length of stay was significantly shorter. This is a scientific as well as clinical sensation, if there ever was one!

The RCT was published in one of the leading journals on this subject (Chest) which is read by most specialists in the field, and it was at the time widely reported. Even today, there is hardly an interview with Prof Frass in which he does not boast about this trial with truly sensational results (only last week, I saw one). If Frass is correct, his findings would revolutionise the lives of thousands of seriously suffering patients at the very brink of death. In other words, it is inconceivable that Frass’ result has not been replicated!

But it hasn’t; at least there is nothing in Medline.

Why not? A risk-free, cheap, universally available and easy to administer treatment for such a severe, life-threatening condition would normally be picked up instantly. There should not be one, but dozens of independent replications by now. There should be several RCTs testing Frass’ therapy and at least one systematic review of these studies telling us clearly what is what.

But instead there is a deafening silence.

Why?

For heaven sakes, why?

The only logical explanation is that many centres around the world did try Frass’ therapy. Most likely they found it does not work and soon dismissed it. Others might even have gone to the trouble of conducting a formal study of Frass’ ‘sensational’ therapy and found it to be ineffective. Subsequently they felt too silly to submit it for publication – who would not laugh at them, if they said they trailed a remedy that was diluted 1: 1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 and found it to be worthless? Others might have written up their study and submitted it for publication, but got rejected by all reputable journals in the field because the editors felt that comparing one placebo to another placebo is not real science.

And this is roughly, how it went with the other ‘positive’ and seemingly rigorous studies of homeopathy as well, I suspect.

Regardless of whether I am correct or not, the fact is that there are no independent replications (if readers know any, please let me know).

Once a sufficiently long period of time has lapsed and no replications of a ‘sensational’ finding did not emerge, the finding becomes unbelievable or bogus – no rational thinker can possibly believe such a results (I for one have not yet met an intensive care specialist who believes Frass’ findings, for instance). Subsequently, it is quietly dropped into the waste-basket of science where it no longer obstructs progress.

The absence of independent replications is therefore a most useful mechanism by which science rids itself of falsehoods.

It seems that homeopathy is such a falsehood.

The plethora of dodgy meta-analyses in alternative medicine has been the subject of a recent post – so this one is a mere update of a regular lament.

This new meta-analysis was to evaluate evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation (LDH). (Call me pedantic, but I prefer meta-analyses that evaluate the evidence FOR AND AGAINST a therapy.) Electronic databases were searched to identify RCTs of acupuncture for LDH, and 30 RCTs involving 3503 participants were included; 29 were published in Chinese and one in English, and all trialists were Chinese.

The results showed that acupuncture had a higher total effective rate than lumbar traction, ibuprofen, diclofenac sodium and meloxicam. Acupuncture was also superior to lumbar traction and diclofenac sodium in terms of pain measured with visual analogue scales (VAS). The total effective rate in 5 trials was greater for acupuncture than for mannitol plus dexamethasone and mecobalamin, ibuprofen plus fugui gutong capsule, loxoprofen, mannitol plus dexamethasone and huoxue zhitong decoction, respectively. Two trials showed a superior effect of acupuncture in VAS scores compared with ibuprofen or mannitol plus dexamethasone, respectively.

The authors from the College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, concluded that acupuncture showed a more favourable effect in the treatment of LDH than lumbar traction, ibuprofen, diclofenac sodium, meloxicam, mannitol plus dexamethasone and mecobalamin, fugui gutong capsule plus ibuprofen, mannitol plus dexamethasone, loxoprofen and huoxue zhitong decoction. However, further rigorously designed, large-scale RCTs are needed to confirm these findings.

Why do I call this meta-analysis ‘dodgy’? I have several reasons, 10 to be exact:

- There is no plausible mechanism by which acupuncture might cure LDH.

- The types of acupuncture used in these trials was far from uniform and included manual acupuncture (MA) in 13 studies, electro-acupuncture (EA) in 10 studies, and warm needle acupuncture (WNA) in 7 studies. Arguably, these are different interventions that cannot be lumped together.

- The trials were mostly of very poor quality, as depicted in the table above. For instance, 18 studies failed to mention the methods used for randomisation. I have previously shown that some Chinese studies use the terms ‘randomisation’ and ‘RCT’ even in the absence of a control group.

- None of the trials made any attempt to control for placebo effects.

- None of the trials were conducted against sham acupuncture.

- Only 10 studies 10 trials reported dropouts or withdrawals.

- Only two trials reported adverse reactions.

- None of these shortcomings were critically discussed in the paper.

- Despite their affiliation, the authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

- All trials were conducted in China, and, on this blog, we have discussed repeatedly that acupuncture trials from China never report negative results.

And why do I find the journal ‘dodgy’?

Because any journal that publishes such a paper is likely to be sub-standard. In the case of ‘Acupuncture in Medicine’, the official journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society, I see such appalling articles published far too frequently to believe that the present paper is just a regrettable, one-off mistake. What makes this issue particularly embarrassing is, of course, the fact that the journal belongs to the BMJ group.

… but we never really thought that science publishing was about anything other than money, did we?

The British Homeopathic Association (BHA) is a registered charity founded in 1902 which aims to promote and develop the study and practice of homeopathy and to advance education and research in the theory and practice of homeopathy. The British Homeopathic Association’s overall priority is to ensure that homeopathy is available to all…

One does not need a particularly keen sense of critical thinking to suspect that this aim is not in line with a charitable status. Homeopathy for all would not be an improvement of public health. On the contrary, the best evidence shows that this concept would lead to a deterioration of it. It would mean less money for effective treatments. Who could argue that this is a charitable aim?

Currently, the BHA seems to focus on preventing that the NHS England stops the reimbursement of homeopathic remedies. They even have initiated a petition to this effect. Here is the full text of this petition, entitled ‘Stop NHS England from removing herbal and homeopathic medicines’:

NHS England is consulting on recommendations to remove herbal and homeopathic medicines from GP prescribing. The medicines cost very little and have no suitable alternatives for many patients. Therefore we call on NHS England to continue to allow doctors to prescribe homeopathy and herbal medicine.

Many NHS patients either suffer such severe side-effects from pharmaceutical drugs they cannot take them, or have been given all other conventional medicines and interventions with no improvement to their health. These patients will continue to need treatment on the NHS and will end up costing the NHS more with conventional prescriptions. There will be no cost savings and patient health will suffer. It is clear stopping homeopathic & herbal prescriptions will not help but hurt the NHS.

I find the arguments and implications of this petition pathetic and misleading. Here is why:

- NHS England is not considering to remove homeopathy from GPs’ prescribing. To the best of my knowledge, the plan is for the NHS to stop paying for homeopathic remedies. If some patients then still want homeopathy, they can get it, but will have to pay for it themselves. That seems entirely fair and rational. Why should we, the tax payers, pay for ineffective treatments?

- Because homeopathic remedies are not effective for any condition, it seems misleading to call them ‘medicines’.

- That homeopathy costs very little is not true; and even if it were correct, it would be neither here or there. The initiative is not primarily about money, it is about the principle: either the NHS adheres to EBM and ethical standards, or not.

- Homeopathy is not a ‘suitable alternative’ for anything, and it is misleading to call it thus.

- Even if NHS England decides against the funding homeopathic remedies, GPs could still be allowed to prescribe them; the only change would be that the NHS would not pay for them.

- Patients who ‘will continue to need treatment on the NHS’ under the described circumstances will not be helped by ineffective treatments like homeopathy.

- It is simply wrong to claim with certainty that there will be no cost savings.

- If the NHS scraps ineffective treatments, patients will suffer not more but less because they might actually receive a treatment that does work.

- It is fairly obvious that stopping to pay for homeopathic remedies will bring progress, help the NHS, patients and the general public.

Nine false or misleading statements in such a short text might well be a new record, even for homeopaths. Perhaps the BHA should apply for an entry in the Guinness Book of Records.

Should we start a petition?

What an odd title, you might think.

Systematic reviews are the most reliable evidence we presently have!

Yes, this is my often-voiced and honestly-held opinion but, like any other type of research, systematic reviews can be badly abused; and when this happens, they can seriously mislead us.

A new paper by someone who knows more about these issues than most of us, John Ioannidis from Stanford university, should make us think. It aimed at exploring the growth of published systematic reviews and meta‐analyses and at estimating how often they are redundant, misleading, or serving conflicted interests. Ioannidis demonstrated that publication of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses has increased rapidly. In the period January 1, 1986, to December 4, 2015, PubMed tags 266,782 items as “systematic reviews” and 58,611 as “meta‐analyses.” Annual publications between 1991 and 2014 increased 2,728% for systematic reviews and 2,635% for meta‐analyses versus only 153% for all PubMed‐indexed items. Ioannidis believes that probably more systematic reviews of trials than new randomized trials are published annually. Most topics addressed by meta‐analyses of randomized trials have overlapping, redundant meta‐analyses; same‐topic meta‐analyses may exceed 20 sometimes.

Some fields produce massive numbers of meta‐analyses; for example, 185 meta‐analyses of antidepressants for depression were published between 2007 and 2014. These meta‐analyses are often produced either by industry employees or by authors with industry ties and results are aligned with sponsor interests. China has rapidly become the most prolific producer of English‐language, PubMed‐indexed meta‐analyses. The most massive presence of Chinese meta‐analyses is on genetic associations (63% of global production in 2014), where almost all results are misleading since they combine fragmented information from mostly abandoned era of candidate genes. Furthermore, many contracting companies working on evidence synthesis receive industry contracts to produce meta‐analyses, many of which probably remain unpublished. Many other meta‐analyses have serious flaws. Of the remaining, most have weak or insufficient evidence to inform decision making. Few systematic reviews and meta‐analyses are both non‐misleading and useful.

The author concluded that the production of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses has reached epidemic proportions. Possibly, the large majority of produced systematic reviews and meta‐analyses are unnecessary, misleading, and/or conflicted.

Ioannidis makes the following ‘Policy Points’:

- Currently, there is massive production of unnecessary, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Instead of promoting evidence‐based medicine and health care, these instruments often serve mostly as easily produced publishable units or marketing tools.

- Suboptimal systematic reviews and meta‐analyses can be harmful given the major prestige and influence these types of studies have acquired.

- The publication of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses should be realigned to remove biases and vested interests and to integrate them better with the primary production of evidence.

Obviously, Ioannidis did not have alternative medicine in mind when he researched and published this article. But he easily could have! Virtually everything he stated in his paper does apply to it. In some areas of alternative medicine, things are even worse than Ioannidis describes.

Take TCM, for instance. I have previously looked at some of the many systematic reviews of TCM that currently flood Medline, based on Chinese studies. This is what I concluded at the time:

Why does that sort of thing frustrate me so much? Because it is utterly meaningless and potentially harmful:

- I don’t know what treatments the authors are talking about.

- Even if I managed to dig deeper, I cannot get the information because practically all the primary studies are published in obscure journals in Chinese language.

- Even if I did read Chinese, I do not feel motivated to assess the primary studies because we know they are all of very poor quality – too flimsy to bother.

- Even if they were formally of good quality, I would have my doubts about their reliability; remember: 100% of these trials report positive findings!

- Most crucially, I am frustrated because conclusions of this nature are deeply misleading and potentially harmful. They give the impression that there might be ‘something in it’, and that it (whatever ‘it’ might be) could be well worth trying. This may give false hope to patients and can send the rest of us on a wild goose chase.

So, to ease the task of future authors of such papers, I decided give them a text for a proper EVIDENCE-BASED conclusion which they can adapt to fit every review. This will save them time and, more importantly perhaps, it will save everyone who might be tempted to read such futile articles the effort to study them in detail. Here is my suggestion for a conclusion soundly based on the evidence, not matter what TCM subject the review is about:

OUR SYSTEMATIC REVIEW HAS SHOWN THAT THERAPY ‘X’ AS A TREATMENT OF CONDITION ‘Y’ IS CURRENTLY NOT SUPPORTED BY SOUND EVIDENCE.

On another occasion, I stated that I am getting very tired of conclusions stating ‘…XY MAY BE EFFECTIVE/HELPFUL/USEFUL/WORTH A TRY…’ It is obvious that the therapy in question MAY be effective, otherwise one would surely not conduct a systematic review. If a review fails to produce good evidence, it is the authors’ ethical, moral and scientific obligation to state this clearly. If they don’t, they simply misuse science for promotion and mislead the public. Strictly speaking, this amounts to scientific misconduct.

In yet another post on the subject of systematic reviews, I wrote that if you have rubbish trials, you can produce a rubbish review and publish it in a rubbish journal (perhaps I should have added ‘rubbish researchers).

And finally this post about a systematic review of acupuncture: it is almost needless to mention that the findings (presented in a host of hardly understandable tables) suggest that acupuncture is of proven or possible effectiveness/efficacy for a very wide array of conditions. It also goes without saying that there is no critical discussion, for instance, of the fact that most of the included evidence originated from China, and that it has been shown over and over again that Chinese acupuncture research never seems to produce negative results.

The main point surely is that the problem of shoddy systematic reviews applies to a depressingly large degree to all areas of alternative medicine, and this is misleading us all.

So, what can be done about it?

My preferred (but sadly unrealistic) solution would be this:

STOP ENTHUSIASTIC AMATEURS FROM PRETENDING TO BE RESEARCHERS!

Research is not fundamentally different from other professional activities; to do it well, one needs adequate training; and doing it badly can cause untold damage.

A few days ago, the German TV ‘FACT’ broadcast a film (it is in German, the bit on homeopathy starts at ~min 20) about a young woman who had her breast cancer first operated but then decided to forfeit subsequent conventional treatments. Instead she chose homeopathy which she received from Dr Jens Wurster at the ‘Clinica Sta Croce‘ in Lucano/Switzerland.

Elsewhere Dr Wurster stated this: Contrary to chemotherapy and radiation, we offer a therapy with homeopathy that supports the patient’s immune system. The basic approach of orthodox medicine is to consider the tumor as a local disease and to treat it aggressively, what leads to a weakening of the immune system. However, when analyzing all studies on cured cancer cases it becomes evident that the immune system is always the decisive factor. When the immune system is enabled to recognize tumor cells, it will also be able to combat them… When homeopathic treatment is successful in rebuilding the immune system and reestablishing the basic regulation of the organism then tumors can disappear again. I’ve treated more than 1000 cancer patients homeopathically and we could even cure or considerably ameliorate the quality of life for several years in some, advanced and metastasizing cases.

The recent TV programme showed a doctor at this establishment confirming that homeopathy alone can cure cancer. Dr Wurster (who currently seems to be a star amongst European homeopaths) is seen lecturing at the 2017 World Congress of Homeopathic Physicians in Leipzig and stating that a ‘particularly rigorous study’ conducted by conventional scientists (the senior author is Harald Walach!, hardly a conventional scientist in my book) proved homeopathy to be effective for cancer. Specifically, he stated that this study showed that ‘homeopathy offers a great advantage in terms of quality of life even for patients suffering from advanced cancers’.

This study did, of course, interest me. So, I located it and had a look. Here is the abstract:

BACKGROUND:

Many cancer patients seek homeopathy as a complementary therapy. It has rarely been studied systematically, whether homeopathic care is of benefit for cancer patients.

METHODS:

We conducted a prospective observational study with cancer patients in two differently treated cohorts: one cohort with patients under complementary homeopathic treatment (HG; n = 259), and one cohort with conventionally treated cancer patients (CG; n = 380). For a direct comparison, matched pairs with patients of the same tumour entity and comparable prognosis were to be formed. Main outcome parameter: change of quality of life (FACT-G, FACIT-Sp) after 3 months. Secondary outcome parameters: change of quality of life (FACT-G, FACIT-Sp) after a year, as well as impairment by fatigue (MFI) and by anxiety and depression (HADS).

RESULTS:

HG: FACT-G, or FACIT-Sp, respectively improved statistically significantly in the first three months, from 75.6 (SD 14.6) to 81.1 (SD 16.9), or from 32.1 (SD 8.2) to 34.9 (SD 8.32), respectively. After 12 months, a further increase to 84.1 (SD 15.5) or 35.2 (SD 8.6) was found. Fatigue (MFI) decreased; anxiety and depression (HADS) did not change. CG: FACT-G remained constant in the first three months: 75.3 (SD 17.3) at t0, and 76.6 (SD 16.6) at t1. After 12 months, there was a slight increase to 78.9 (SD 18.1). FACIT-Sp scores improved significantly from t0 (31.0 – SD 8.9) to t1 (32.1 – SD 8.9) and declined again after a year (31.6 – SD 9.4). For fatigue, anxiety, and depression, no relevant changes were found. 120 patients of HG and 206 patients of CG met our criteria for matched-pairs selection. Due to large differences between the two patient populations, however, only 11 matched pairs could be formed. This is not sufficient for a comparative study.

CONCLUSION:

In our prospective study, we observed an improvement of quality of life as well as a tendency of fatigue symptoms to decrease in cancer patients under complementary homeopathic treatment. It would take considerably larger samples to find matched pairs suitable for comparison in order to establish a definite causal relation between these effects and homeopathic treatment.

_________________________________________________________________

Even the abstract makes several points very clear, and the full text confirms further embarrassing details:

- The patients in this study received homeopathy in addition to standard care (the patient shown in the film only had homeopathy until it was too late, and she subsequently died, aged 33).

- The study compared A+B with B alone (A=homeopathy, B= standard care). It is hardly surprising that the additional attention of A leads to an improvement in quality of life. It is arguably even unethical to conduct a clinical trial to demonstrate such an obvious outcome.

- The authors of this paper caution that it is not possible to conclude that a causal relationship between homeopathy and the outcome exists.

- This is true not just because of the small sample size, but also because of the fact that the two groups had not been allocated randomly and therefore are bound to differ in a whole host of variables that have not or cannot be measured.

- Harald Walach, the senior author of this paper, held a position which was funded by Heel, Baden-Baden, one of Germany’s largest manufacturer of homeopathics.

- The H.W.& J.Hector Foundation, Germany, and the Samueli Institute, provided the funding for this study.

In the film, one of the co-authors of this paper, the oncologist HH Bartsch from Freiburg, states that Dr Wurster’s interpretation of this study is ‘dishonest’.

I am inclined to agree.

We have repeatedly discussed the journal ‘Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine’ (see for instance here and here). The journal has recently done something remarkable and seemingly laudable: it retracted an article titled “Psorinum Therapy in Treating Stomach, Gall Bladder, Pancreatic, and Liver Cancers: A Prospective Clinical Study” due to concerns about the ethics, authorship, quality of reporting, and misleading conclusions.***

Aradeep and Ashim Chatterjee own and manage the Critical Cancer Management Research Centre and Clinic (CCMRCC), the private clinic to which they are affiliated. The methods state “The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB approval Number: 2001–05) of the CCMRCC” in 2001, but a 2014 review of Psorinum therapy said CCMRCC was founded in 2008. The study states “The participants received the drug Psorinum along with allopathic and homeopathic supportive treatments without trying conventional or any other investigational cancer treatments”; withholding conventional cancer treatment raises ethical concerns.

We asked the authors and their institutions for documentation of the ethics approval, the study protocol, and a blank copy of the informed consent form. However, the corresponding author, Aradeep Chatterjee, was reported to have been arrested in June 2017 for allegedly practising medicine without the correct qualifications and his co-author and father Ashim Chatterjee was reported to have been arrested in August; the Chatterjees and their legal representative did not respond to our queries. The co-authors Syamsundar Mandal, Sudin Bhattacharya, and Bishnu Mukhopadhyay said they did not agree to be authors of the article and were not aware of its submission; co-author Jaydip Biswas did not respond.

A member of the editorial board noted that although the discussion stated that “The limitation of this study is that it did not have any placebo or treatment control arm; therefore, it cannot be concluded that Psorinum Therapy is effective in improving the survival and the quality of life of the participants due to the academic rigours of the scientific clinical trials”, the abstract was misleading because it implied Psorinum therapy is effective in cancer treatment. The study design was described as a “prospective observational clinical trial”, but it cannot have been both observational and a clinical trial.

(*** while I wrote this blog (13/3/18) the abstract of this paper was still available on Medline without a retraction notice)

________________________________________________________________________________

In case you wonder what ‘psorinum therapy’ is, this website explains:

A cancer specialist and Psorinum clinical researcher, Aurodeep Chaterjee, believes Psorinum Therapy is less time consuming and more economical for treatment of cancer. ‘The advantage of this treatment is that the patient can continue this treatment while staying home and the hospitalization is less required,’ said Chaterjee. He added that it’s an immunotherapy treatment in which the medicine is in liquid form and the technique of consumption is oral.

Though no chemo or radiation sessions are required in it but they can be used parallel to it depending upon the stage of the cancer. He claimed that more than 30 types of cancers could be treated from this therapy. Some of them include gastrointestinal cancer, liver cancer, gall bladder cancer, ovarian cancer, stomach cancer, etc. The process requires two months duration in which the patient has to undergo 12 cycles and the cost is just Rs 5000. Moli Rapoor 55, software engineer from USA who is suffering from ovarian cancer said on Thursday (June 20) that after three chemo cycles when her cancer did not cure after being diagnosed in 2008, she decided to take up Psorinum therapy.

_________________________________________________________________________________

I am sorry, but the retraction of such a paper is far less laudable than it seems – it should not have been retracted, but it should have never been published in the first place. There are multiple points where the reviewers’ and editors’ alarm bells should have started ringing loud and clear. Take, for instance, this note at the end of the paper:

Funding

Dr. Rabindranath Chatterjee Memorial Cancer Trust provided funding for this study.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

I think that this should have been a give-away, considering the names of the authors: Chatterjee A1, Biswas J, Chatterjee A, Bhattacharya S, Mukhopadhyay B, Mandal S.

What this story shows, in my view, is that the journal ‘Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine’ (EBCAM) operates an unacceptably poor system of peer-review, and is led by an editor who seems to shut both eyes when deciding about publication or rejection. And why would an editor shut his/her eyes to abuse? Perhaps the journal’s interesting business model provides an explanation? Here is what I wrote about it previously:

What I fail to understand is why so many researchers send their papers to this journal. In 2015, EBCAM published just under 1000 (983 to be exact) papers. This is not far from half of all Medline-listed articles on alternative medicine (2056 in total).

To appreciate these figures – and this is where it gets not just puzzling but intriguing, in my view – we need to know that EBCAM charges a publication fee of US$ 2500. That means the journal has an income of about US$ 2 500 000 per annum!

END OF QUOTE

To put it in a nutshell: in healthcare, fraud and greed can cause enormous harm.