yoga

While many of us are wondering what SCAM will be promoted next for the corona pandemic, the editor of the infamous JCAM thought it wise to publish this note along with an article advertising the wonders of Ayurvedic medicine and yoga for the corona-virus entitled: ‘Public Health Approach of Ayurveda and Yoga for COVID-19 Prophylaxis‘.

Here are John Weeks’ remarks:

National governments are deeply divided over whether traditional, complementary and integrative practices have value for human beings relative to COVID-19. We witness a double standard. Medical doctors explore off-label uses of pharmaceutical agents that may have some suggestive research while evidence that indicates potential utility of natural products, practices and practitioners is often dismissed. In this Invited Commentary, a long-time JACM Editorial Board member Bhushan Patwardhan, PhD, from the AYUSH Center of Excellence, Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at the Savitribai Phule Pune University, India and colleagues from multiple institutions make a case for the potential roles of Ayurvedic medicine and Yoga as supportive measures in self-care and treatment. Patwardhan is a warrior for enhancing scientific standards in traditional medicine in India. Patwardhan was recently appointed by the Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India, as Chairman of an 18 member expert group known as “Interdisciplinary AYUSH Research and Development Taskforce” for initiating, coordinating and monitoring efforts against COVID-19. He was last seen here in an invited commentary entitled “Contesting Predators: Cleaning Up Trash in Science” (JACM, October 2019). We are pleased to have this opportunity to share the recommended approaches, the science, and the historic references as part of the global effort to leave no stone unturned in best preparing our populations to withstand COVID-19 and future viral threats. – John Weeks, Editor-in-Chief, JACM

His remarks are, I think, worthy of four very brief comments:

- As far as I can see, national governments and their advisors struggle to make sense of the rapidly changing situation. In all the confusion, they are, however, very clear about one thing: traditional, complementary and integrative practices have no real value for human beings relative to COVID-19.

- The double standards Weeks bemoans do not exist. There are dozens of studies currently on their way testing virtually any therapeutic option that shows even the smallest shimmer of hope. Testing implausible options only because some quacks feel neglected would be the last thing the world needs in the present situation.

- Weeks claims that ‘evidence that indicates potential utility of natural products, practices and practitioners is often dismissed’. What evidence? The article published alongside his remarks is free of what anyone with a thinking brain might call ‘evidence’. If there is evidence, Weeks or anyone else should approach the experts responsible for conducting the current trials; I am sure that they would listen and be only too happy to consider any reasonable option.

- The Indian Ministry of AYUSH has indeed been promoting all sorts of quackery for the corona-virus. This behaviour is likely to cause many fatalities in India. It should be squarely condemned and not promoted as Weeks seem to think.

Today is Valentine’s Day, a good moment to take a critical look at some of the libido-boosters so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) has to offer. The Internet offers plenty; this website, for instance, advertises over 20 different natural (mostly botanical) products. But such sites are typically thin on evidence.

A quick Medline search locates plenty of research. Much of it seems to be on rats which is not so relevant – unless, of course, your husband is a rat. In terms of clinical trials, Medline too is not all that informative. Here are some of the studies I found:

Eurycoma longifolia is reputed as an aphrodisiac and remedy for decreased male libido. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, parallel group study was carried out to investigate the clinical evidence of E. longifolia in men. The 12-week study in 109 men between 30 and 55 years of age consisted of either treatment of 300 mg of water extract of E. longifolia (Physta) or placebo. Primary endpoints were the Quality of Life investigated by SF-36 questionnaire and Sexual Well-Being investigated by International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and Sexual Health Questionnaires (SHQ); Seminal Fluid Analysis (SFA), fat mass and safety profiles. Repeated measures ANOVA analysis was used to compare changes in the endpoints. The E. longifolia (EL) group significantly improved in the domain Physical Functioning of SF-36, from baseline to week 12 compared to placebo (P = 0.006) and in between group at week 12 (P = 0.028). The EL group showed higher scores in the overall Erectile Function domain in IIEF (P < 0.001), sexual libido (14% by week 12), SFA- with sperm motility at 44.4%, and semen volume at 18.2% at the end of treatment. Subjects with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m(2) significantly improved in fat mass lost (P = 0.008). All safety parameters were comparable to placebo.

Yoga is a popular form of complementary and alternative treatment. It is practiced both in developing and developed countries. Use of yoga for various bodily ailments is recommended in ancient ayvurvedic (ayus = life, veda = knowledge) texts and is being increasingly investigated scientifically. Many patients and yoga protagonists claim that it is useful in sexual disorders. We are interested in knowing if it works for patients with premature ejaculation (PE) and in comparing its efficacy with fluoxetine, a known treatment option for PE. Aim: To know if yoga could be tried as a treatment option in PE and to compare it with fluoxetine. Methods: A total of 68 patients (38 yoga group; 30 fluoxetine group) attending the outpatient department of psychiatry of a tertiary care hospital were enrolled in the present study. Both subjective and objective assessment tools were administered to evaluate the efficacy of the yoga and fluoxetine in PE. Three patients dropped out of the study citing their inability to cope up with the yoga schedule as the reason. Main outcome measure: Intravaginal ejaculatory latencies in yoga group and fluoxetine control groups. Results: We found that all 38 patients (25-65.7% = good, 13-34.2% = fair) belonging to yoga and 25 out of 30 of the fluoxetine group (82.3%) had statistically significant improvement in PE. Conclusions: Yoga appears to be a feasible, safe, effective and acceptable nonpharmacological option for PE. More studies involving larger patients could be carried out to establish its utility in this condition.

Antidepressants including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are known to cause secondary sexual dysfunction with prevalence rates as high as 50%-90%. Emerging research is establishing that acupuncture may be an effective treatment modality for sexual dysfunction including impotence, loss of libido, and an inability to orgasm. Objectives: The purpose of this study was to examine the potential benefits of acupuncture in the management of sexual dysfunction secondary to SSRIs and SNRIs. Subjects: Practitioners at the START Clinic referred participants experiencing adverse sexual events from their antidepressant medication for acupuncture treatment at the Mood and Anxiety Disorders, a tertiary care mood and anxiety disorder clinic in Toronto. Design: Participants received a Traditional Chinese Medicine assessment and followed an acupuncture protocol for 12 consecutive weeks. The acupuncture points used were Kidney 3, Governing Vessel 4, Urinary Bladder 23, with Heart 7 and Pericardium 6. Participants also completed a questionnaire package on a weekly basis. Outcomes measured: The questionnaire package consisted of self-report measures assessing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and various aspects of sexual function. Results: Significant improvement among male participants was noted in all areas of sexual functioning, as well as in both anxiety and depressive symptoms. Female participants reported a significant improvement in libido and lubrication and a nonsignificant trend toward improvement in several other areas of function. Conclusions: This study suggests a potential role for acupuncture in the treatment of the sexual side-effects of SSRIs and SNRIs as well for a potential benefit of integrating medical and complementary and alternative practitioners.

The primary objectives were to compare the efficacy of extracts of the plant Tribulus terrestris (TT; marketed as Tribestan), in comparison with placebo, for the treatment of men with erectile dysfunction (ED) and with or without hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), as well as to monitor the safety profile of the drug. The secondary objective was to evaluate the level of lipids in blood during treatment. Participants and design: Phase IV, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in parallel groups. This study included 180 males aged between 18 and 65 years with mild or moderate ED and with or without HSDD: 90 were randomized to TT and 90 to placebo. Patients with ED and hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome were included in the study. In the trial, an herbal medicine intervention of Bulgarian origin was used (Tribestan®, Sopharma AD). Each Tribestan film-coated tablet contains the active substance Tribulus terrestris, herba extractum siccum (35-45:1) 250mg which is standardized to furostanol saponins (not less than 112.5mg). Each patient received orally 3×2 film-coated tablets daily after meals, during the 12-week treatment period. At the end of each month, participants’ sexual function, including ED, was assessed by International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Questionnaire and Global Efficacy Question (GEQ). Several biochemical parameters were also determined. The primary outcome measure was the change in IIEF score after 12 weeks of treatment. Complete randomization (random sorting using maximum allowable% deviation) with an equal number of patients in each sequence was used. This randomization algorithm has the restriction that unequal treatment allocation is not allowed; that is, all groups must have the same target sample size. Patients, investigational staff, and data collectors were blinded to treatment. All outcome assessors were also blinded to group allocation. Results: 86 patients in each group completed the study. The IIEF score improved significantly in the TT group compared with the placebo group (Р<0.0001). For intention-to-treat (ITT) there was a statistically significant difference in change from baseline of IIEF scores. The difference between TT and placebo was 2.70 (95% CI 1.40, 4.01) for the ITT population. A statistically significant difference between TT and placebo was found for Intercourse Satisfaction (p=0.0005), Orgasmic Function (p=0.0325), Sexual Desire (p=0.0038), Overall Satisfaction (p=0.0028) as well as in GEQ responses (p<0.0001), in favour of TT. There were no differences in the incidence of adverse events (AEs) between the two groups and the therapy was well tolerated. There were no drug-related serious AEs. Following the 12-week treatment period, significant improvement in sexual function was observed with TT compared with placebo in men with mild to moderate ED. TT was generally well tolerated for the treatment of ED.

What makes me suspicious about these trials is that:

- they are mostly on the flimsy side,

- there are as good as no independent replications,

- they all report positive outcomes. I was unable to find a single study where the authors concluded: SORRY, BUT THIS STUFF IS USELESS!

Disappointed with the quality and the content of the existing trials, I am now off to buy some oysters!

Some people seem to think that all so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) is ineffective, harmful or both. And some believe that I am hell-bent to make sure that this message gets out there. I recommend that these guys read my latest book or this 2008 article (sadly now out-dated) and find those (admittedly few) SCAMs that demonstrably generate more good than harm.

The truth, as far as this blog is concerned, is that I am constantly on the lookout to review research that shows or suggests that a therapy is effective or a diagnostic technique is valid (if you see such a paper that is sound and new, please let me know). And yesterday, I have been lucky:

This paper has just been presented at the ESC Congress in Paris.

Its authors are: A Pandey (1), N Huq (1), M Chapman (1), A Fongang (1), P Poirier (2)

(1) Cambridge Cardiac Care Centre – Cambridge – Canada

(2) Université Laval, Faculté de Pharmacie – Laval – Canada

Here is the abstract in full:

Yes, this study was small, too small to draw far-reaching conclusions. And no, we don’t know what precisely ‘yoga’ entailed (we need to wait for the full publication to get this information plus all the other details needed to evaluate the study properly). Yet, this is surely promising: yoga has few adverse effects, is liked by many consumers, and could potentially help millions to reduce their cardiovascular risk. What is more, there is at least some encouraging previous evidence.

But what I like most about this abstract is the fact that the authors are sufficiently cautious in their conclusions and even state ‘if these results are validated…’

SCAM-researchers, please take note!

A recent blog-post pointed out that the usefulness of yoga in primary care is doubtful. Now we have new data to shed some light on this issue.

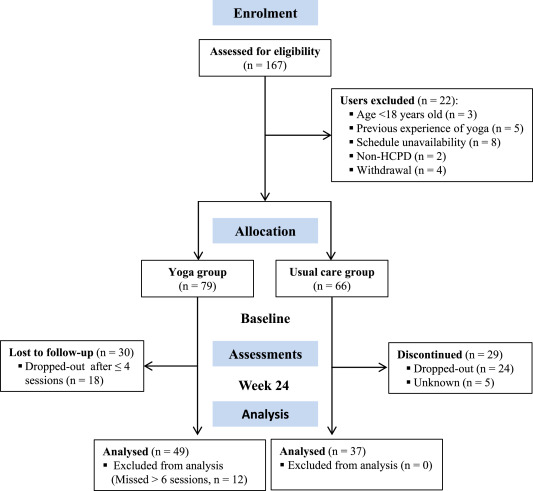

The new paper reports a ‘prospective, longitudinal, quasi-experimental study‘. Yoga group (n= 49) underwent 24-weeks program of one-hour yoga sessions. The control group had no yoga.

Participation was voluntary and the enrolment strategy was based on invitations by health professionals and advertising in the community (e.g., local newspaper, health unit website and posters). Users willing to participate were invited to complete a registration form to verify eligibility criteria.

The endpoints of the study were:

- quality of life,

- psychological distress,

- satisfaction level,

- adherence rate.

The yoga routine consisted of breathing exercises, progressive articular and myofascial warming-up, followed by surya namascar (sun salutation sequence; adapted to the physical condition of each participant), alignment exercises, and postural awareness. Practice also included soft twists of the spine, reversed and balance postures, as well as concentration exercises. During the sessions, the instructor discussed some ethical guidelines of yoga, as for example, non-violence (ahimsa) and truthfulness (satya), to allow the participant to have a safer and integrated practice. In addition, the participants were encouraged to develop their awareness of the present moment and their body sensations, through a continuous process of self-consciousness, keeping a distance between body sensations and the emotional experience. The instructor emphasized the connection between breathing and movement. Each session ended with a guided deep relaxation (yoga nidra; 5–10 min), followed by a meditation practice (5–10 min).

The results of the study showed that the patients in the yoga group experienced a significant improvement in all domains of quality of life and a reduction of psychological distress. Linear regression analysis showed that yoga significantly improved psychological quality of life.

The authors concluded that yoga in primary care is feasible, safe and has a satisfactory adherence, as well as a positive effect on psychological quality of life of participants.

Are the authors’ conclusions correct?

I think not!

Here are some reasons for my judgement:

- The study was far to small to justify far-reaching conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of yoga.

- There were relatively high numbers of drop-outs, as seen in the graph above. Despite this fact, no intention to treat analysis was used.

- There was no randomisation, and therefore the two groups were probably not comparable.

- Participants of the experimental group chose to have yoga; their expectations thus influenced the outcomes.

- There was no attempt to control for placebo effects.

- The conclusion that yoga is safe would require a sample size that is several dimensions larger than 49.

In conclusion, this study fails to show that yoga has any value in primary care.

PS

Oh, I almost forgot: and yoga is also satanic, of course (just like reading Harry Potter!).

You probably know what yoga is. But what is FODMAP? It stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols, more commonly known as carbohydrates. In essence, FODMAPs are carbohydrates found in a wide range of foods including onions, garlic, mushrooms, apples, lentils, rye and milk. These sugars are poorly absorbed, pass through the small intestine and enter the colon . There they are fermented by bacteria a process that produces gas which stretches the sensitive bowel causing bloating, wind and sometimes even pain. This can also cause water to move into and out of the colon, causing diarrhoea, constipation or a combination of both. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) makes people more susceptible to such problems.

During a low FODMAP diet these carbohydrates are eliminated usually for six to eight weeks. Subsequently, small amounts of FODMAP foods are gradually re-introduced to find a level of symptom-free tolerance. The question is, does the low FODMAP diet work?

This study examined the effect of a yoga-based intervention vs a low FODMAP diet on patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Fifty-nine patients with IBS undertook a randomised controlled trial involving yoga or a low FODMAP diet for 12 weeks. Patients in the yoga group received two sessions weekly, while patients in the low FODMAP group received a total of three sessions of nutritional counselling. The primary outcome was a change in gastrointestinal symptoms (IBS-SSS). Secondary outcomes explored changes in quality of life (IBS-QOL), health (SF-36), perceived stress (CPSS, PSQ), body awareness (BAQ), body responsiveness (BRS) and safety of the interventions. Outcomes were examined in weeks 12 and 24 by assessors “blinded” to patients’ group allocation.

No statistically significant difference was found between the intervention groups, with regard to IBS-SSS score, at either 12 or 24 weeks. Within-group comparisons showed statistically significant effects for yoga and low FODMAP diet at both 12 and 24 weeks. Comparable within-group effects occurred for the other outcomes. One patient in each intervention group experienced serious adverse events and another, also in each group, experienced nonserious adverse events.

The authors concluded that patients with irritable bowel syndrome might benefit from yoga and a low-FODMAP diet, as both groups showed a reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms. More research on the underlying mechanisms of both interventions is warranted, as well as exploration of potential benefits from their combined use.

Technically, this study is an equivalence study comparing two interventions. Such trials only make sense, if one of the two treatments have been proven to be effective. This is, however, not the case. Moreover, equivalence studies require much larger sample sizes than the 59 patients included here.

What follows is that this trial is pure pseudoscience and the positive conclusion of this study is not warranted. The authors have, in my view, demonstrated a remarkable level of ignorance regarding clinical research. None of this is all that unusual in the realm of alternative medicine; sadly, it seems more the rule than the exception.

What might make this lack of research know-how more noteworthy is something else: starting in January 2019, one of the lead authors of this piece of pseudo-research (Prof. Dr. med. Jost Langhorst) will be the director of the new Stiftungslehrstuhl “Integrative Medizin” am Klinikum Bamberg (clinic and chair of integrative medicine in Bamberg, Germany).

This does not bode well, does it?

I came across this article; it is neither new nor particularly scientific. Yet I believe it is sufficiently remarkable to alert you to it, quote a little from it, and hopefully make you chuckle a bit:

The Vatican’s top exorcist has spoken out in condemnation of yoga … , branding [it] as “Satanic” acts that lead[s] to “demonic possession”. Father Cesare Truqui has warned that the Catholic Church has seen a recent spike in worldwide reports of people becoming possessed by demons and that the reason for the sudden uptick is the rise in popularity of pastimes such as watching Harry Potter movies and practicing Vinyasa.

Professor Giuseppe Ferrari … says that … activities such as yoga, “summon satanic spirits” … Monsignor Luigi Negri, the archbishop of Ferrara-Comacchio, who also attended the Vatican crisis meeting, claimed that homosexuality is “another sign” that “Satan is in the Vatican”. The Independent reports: Father Cesare says he’s seen many an individual speaking in tongues and exhibiting unearthly strength, two attributes that his religion says indicate the possibility of evil spirits inhabiting a person’s body. “There are those who try to turn people into vampires and make them drink other people’s blood, or encourage them to have special sexual relations to obtain special powers,” stated Professor Ferrari at the meeting. “These groups are attracted by the so-called beautiful young vampires that we’ve seen so much of in recent years.”

Is yoga about worshiping Hindu gods, or is it about engaging in advanced stretching and exercise? At its roots, yoga is said to have originated from the ancient worship of Hindu gods, with the various poses representing unique forms of paying homage to these entities. From this, other religions such as Catholicism and Christianity have concluded that the practice is out of sync with their own and that it may result in demonic spirits entering a person’s body.

… Father Truqui sees yoga as being satanic, claiming that “it leads to evil just like reading Harry Potter.” And in order to deal with the consequences of this, his religion has had to bring on an additional six exorcists, bringing the total number to 12, just to deal with what he says is a 100% rise in the number of requests for exorcisms over the past 15 years. “The ministry of performing an exorcism is little known among priests … It’s like training to be a journalist without knowing how to do an interview.” At the same time, Father Amorth admits that the Roman Catholic Church’s notoriety for all kinds of perverted sex scandals is also indicative of demonic activity – he stated that it represents proof that “the Devil is at work inside the Vatican.” “There’s homosexual marriage, homosexual adoption, IVF [in vitro fertilization] and a host of other things,” added Monsignor Luigi Negri, the archbishop of Ferrara-Comacchio, about what he says is evidence of the existential evil in society. “There’s the glamorous appearance of the negation of man as defined by the Bible.”

END OF QUOTES

Speechless?

Me too!

Just one thought, if I may: according to Father Truqui, the most satanic man must be a ‘perverted’ catholic priest practising Yoga and reading Harry Potter!

Having yesterday been to a ‘Skeptics in the Pub’ event on MEDITATION in Cambridge (my home town since last year) I had to think about the subject quite a bit. As I have hardly covered this topic on my blog, I am today trying to briefly summarise my view on it.

The first thing that strikes me when looking at the evidence on meditation is that it is highly confusing. There seem to be:

- a lack of clear definitions,

- hundreds of studies, most of which are of poor or even very poor quality,

- lots of people with ’emotional baggage’,

- plenty of strange links to cults and religions,

- dozens of different meditation methods and regimen,

- unbelievable claims by enthusiasts,

- lots of weirdly enthusiastic followers.

What was confirmed yesterday is the fact that, once we look at the reliable medical evidence, we are bound to find that the health claims of various meditation techniques are hugely exaggerated. There is almost no strong evidence to suggest that meditation does affect any condition. The small effects that do emerge from some meta-analyses could easily be due to residual bias and confounding; it is not possible to rigorously control for placebo effects in clinical trials of meditation.

Another thing that came out clearly yesterday is the fact that meditation might not be as risk-free as it is usually presented. Several cases of psychoses after meditation are on record; some of these are both severe and log-lasting. How often do they happen? Nobody knows! Like with most alternative therapies, there is no reporting system in place that could possibly give us anything like a reliable answer.

For me, however, the biggest danger with (certain forms of) meditation is not the risk of psychosis. It is the risk of getting sucked into a cult that then takes over the victim and more or less destroys his or her personality. I have seen this several times, and it is a truly frightening phenomenon.

In our now 10-year-old book THE DESKTOP GUIDE TO COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE, we included a chapter on meditation. It concluded that “meditation appears to be safe for most people and those with sufficient motivation to practise regularly will probably find a relaxing experience. Evidence for effectiveness in any indication is week.” Even today, this is not far off the mark, I think. If I had to re-write it now, I would perhaps mention the potential for harm and also add that, as a therapy, the risk/benefit balance of meditation fails to be convincingly positive.

PS

I highly recommend ‘Skeptics in the Pub’ events to anyone who likes stimulating talks and critical thinking.

The media have (rightly) paid much attention to the three Lancet-articles on low back pain (LBP) which were published this week. LBP is such a common condition that its prevalence alone renders it an important subject for us all. One of the three papers covers the treatment and prevention of LBP. Specifically, it lists various therapies according to their effectiveness for both acute and persistent LBP. The authors of the article base their judgements mainly on published guidelines from Denmark, UK and the US; as these guidelines differ, they attempt a synthesis of the three.

Several alternative therapist organisations and individuals have consequently jumped on the LBP bandwagon and seem to feel encouraged by the attention given to the Lancet-papers to promote their treatments. Others have claimed that my often critical verdicts of alternative therapies for LBP are out of line with this evidence and asked ‘who should we believe the international team of experts writing in one of the best medical journals, or Edzard Ernst writing on his blog?’ They are trying to create a division where none exists,

The thing is that I am broadly in agreement with the evidence presented in Lancet-paper! But I also know that things are a bit more complex.

Below, I have copied the non-pharmacological, non-operative treatments listed in the Lancet-paper together with the authors’ verdicts regarding their effectiveness for both acute and persistent LBP. I find no glaring contradictions with what I regard as the best current evidence and with my posts on the subject. But I feel compelled to point out that the Lancet-paper merely lists the effectiveness of several therapeutic options, and that the value of a treatment is not only determined by its effectiveness. Crucial further elements are a therapy’s cost and its risks, the latter of which also determines the most important criterion: the risk/benefit balance. In my version of the Lancet table, I have therefore added these three variables for non-pharmacological and non-surgical options:

| EFFECTIVENESS ACUTE LBP | EFFECTIVENESS PERSISTENT LBP | RISKS | COSTS | RISK/BENEFIT BALANCE | |

| Advice to stay active | +, routine | +, routine | None | Low | Positive |

| Education | +, routine | +, routine | None | Low | Positive |

| Superficial heat | +/- | Ie | Very minor | Low to medium | Positive (aLBP) |

| Exercise | Limited | +/-, routine | Very minor | Low | Positive (pLBP) |

| CBT | Limited | +/-, routine | None | Low to medium | Positive (pLBP) |

| Spinal manipulation | +/- | +/- | vfbmae sae |

High | Negative |

| Massage | +/- | +/- | Very minor | High | Positive |

| Acupuncture | +/- | +/- | sae | High | Questionable |

| Yoga | Ie | +/- | Minor | Medium | Questionable |

| Mindfulness | Ie | +/- | Minor | Medium | Questionable |

| Rehab | Ie | +/- | Minor | Medium to high | Questionable |

Routine = consider for routine use

+/- = second line or adjunctive treatment

Ie = insufficient evidence

Limited = limited use in selected patients

vfbmae = very frequent, minor adverse effects

sae = serious adverse effects, including deaths, are on record

aLBP = acute low back pain

The reason why my stance, as expressed on this blog and elsewhere, is often critical about certain alternative therapies is thus obvious and transparent. For none of them (except for massage) is the risk/benefit balance positive. And for spinal manipulation, it even turns out to be negative. It goes almost without saying that responsible advice must be to avoid treatments for which the benefits do not demonstrably outweigh the risks.

I imagine that chiropractors, osteopaths and acupuncturists will strongly disagree with my interpretation of the evidence (they might even feel that their cash-flow is endangered) – and I am looking forward to the discussions around their objections.

As I have stated repeatedly, I am constantly on the look-out for positive news about alternative medicine. Usually, I find plenty – but when I scrutinise it, it tends to crumble in the type of misleading report that I often write about on this blog. Truly good research in alternative medicine is hard to find, and results that are based on rigorous science and show a positive finding are a bit like gold-dust.

But hold on, today I have something!

This systematic review was aimed at determining whether physical exercise is effective in improving cognitive function in the over 50s. The authors evaluated all randomised controlled trials of physical exercise interventions in community-dwelling adults older than 50 years with an outcome measure of cognitive function.

39 studies were included in the systematic review. Analysis of 333 dependent effect sizes from 36 studies showed that physical exercise improved cognitive function. Interventions of aerobic exercise, resistance training, multicomponent training and tai chi, all had significant point estimates. When exercise prescription was examined, a duration of 45–60 min per session and at least moderate intensity, were associated with benefits to cognition. The results of the meta-analysis were consistent and independent of the cognitive domain tested or the cognitive status of the participants.

The authors concluded that physical exercise improved cognitive function in the over 50s, regardless of the cognitive status of participants. To improve cognitive function, this meta-analysis provides clinicians with evidence to recommend that patients obtain both aerobic and resistance exercise of at least moderate intensity on as many days of the week as feasible, in line with current exercise guidelines.

But this is not alternative medicine, I hear you say.

You are right, mostly, it isn’t. There were a few RCTs of tai chi and yoga, but the majority was of conventional exercise. Moreover, most of these ‘alternative’ RCTs were less convincing than the conventional RCTs; here is one of the former category:

Community-dwelling older adults (N = 118; mean age = 62.0) were randomized to one of two groups: a Hatha yoga intervention or a stretching-strengthening control. Both groups participated in hour-long exercise classes 3×/week over the 8-week study period. All participants completed established tests of executive function including the task switching paradigm, n-back and running memory span at baseline and follow-up. Analysis of covariances showed significantly shorter reaction times on the mixed and repeat task switching trials (partial η(2) = .04, p < .05) for the Hatha yoga group. Higher accuracy was recorded on the single trials (partial η(2) = .05, p < .05), the 2-back condition of the n-back (partial η(2) = .08, p < .001), and partial recall scores (partial η(2) = .06, p < .01) of running span task.

I just wanted to be generous and felt the need to report a positive result. I guess, this just shows how devoid of rigorous research generating a positive finding alternative medicine really is.

Of course, there are many readers of this blog who are convinced that their pet therapy is supported by excellent evidence. For them, I have this challenge: if you think you have good evidence for an alternative therapy, show it to me (send it to me via the ‘contact’ option of this blog or post the link as a comment below). Please note that any evidence I would consider analysing in some detail (writing a full blog post about it) would need to be recent, peer-reviewed and rigorous.

The title of the press-release was impressive: ‘Columbia and Harvard Researchers Find Yoga and Controlled Breathing Reduce Depressive Symptoms’. It certainly awoke my interest and I looked up the original article. Sadly, it also awoke the interest of many journalists, and the study was reported widely – and, as we shall see, mostly wrongly.

According to its authors, the aims of this study were “to assess the effects of an intervention of Iyengar yoga and coherent breathing at five breaths per minute on depressive symptoms and to determine optimal intervention yoga dosing for future studies in individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD)”.

Thirty two subjects were randomized to either the high-dose group (HDG) or low-dose group (LDG) for a 12-week intervention of three or two intervention classes per week, respectively. Eligible subjects were 18–64 years old with MDD, had baseline Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) scores ≥14, and were either on no antidepressant medications or on a stable dose of antidepressants for ≥3 months. The intervention included 90-min classes plus homework. Outcome measures were BDI-II scores and intervention compliance.

Fifteen HDG and 15 LDG subjects completed the intervention. BDI-II scores at screening and compliance did not differ between groups. BDI-II scores declined significantly from screening (24.6 ± 1.7) to week 12 (6.0 ± 3.8) for the HDG (–18.6 ± 6.6; p < 0.001), and from screening (27.7 ± 2.1) to week 12 (10.1 ± 7.9) in the LDG. There were no significant differences between groups, based on response (i.e., >50% decrease in BDI-II scores; p = 0.65) for the HDG (13/15 subjects) and LDG (11/15 subjects) or remission (i.e., number of subjects with BDI-II scores <14; p = 1.00) for the HDG (14/15 subjects) and LDG (13/15 subjects) after the 12-week intervention, although a greater number of subjects in the HDG had 12-week BDI-II scores ≤10 (p = 0.04).

The authors concluded that this dosing study provides evidence that participation in an intervention composed of Iyengar yoga and coherent breathing is associated with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms for individuals with MDD, both on and off antidepressant medications. The HDG and LDG showed no significant differences in compliance or in rates of response or remission. Although the HDG had significantly more subjects with BDI-II scores ≤10 at week 12, twice weekly classes (plus home practice) may rates of response or remission. Although the HDG, thrice weekly classes (plus home practice) had significantly more subjects with BDI-II scores ≤10 at week 12, the LDG, twice weekly classes (plus home practice) may constitute a less burdensome but still effective way to gain the mood benefits from the intervention. This study supports the use of an Iyengar yoga and coherent breathing intervention as a treatment to alleviate depressive symptoms in MDD.

The authors also warn that this study must be interpreted with caution and point out several limitations:

- the small sample size,

- the lack of an active non-yoga control (both groups received Iyengar yoga plus coherent breathing),

- the supportive group environment and multiple subject interactions with research staff each week could have contributed to the reduction in depressive symptoms,

- the results cannot be generalized to MDD with more acute suicidality or more severe symptoms.

In the press-release, we are told that “The practical findings for this integrative health intervention are that it worked for participants who were both on and off antidepressant medications, and for those time-pressed, the two times per week dose also performed well,” says The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine Editor-in-Chief John Weeks

At the end of the paper, we learn that the authors, Dr. Brown and Dr. Gerbarg, teach and have published Breath∼Body∼Mind©, a technique that uses coherent breathing. Dr. Streeter is certified to teach Breath∼Body∼Mind©. No competing financial interests exist for the remaining authors.

Taking all of these issues into account, my take on this study is different and a little more critical:

- The observed effects might have nothing at all to do with the specific intervention tested.

- The trial was poorly designed.

- The aims of the study are not within reach of its methodology.

- The trial lacked a proper control group.

- It was published in a journal that has no credibility.

- The limitations outlined by the authors are merely the tip of an entire iceberg of fatal flaws.

- The press-release is irresponsibly exaggerated.

- The authors have little incentive to truly test their therapy and seem to use research as a means of promoting their business.