systematic review

I only recently came across this review; it was published a few years ago but is still highly relevant. It summarizes the evidence of controlled clinical studies of TCM for cancer.

The authors searched all the controlled clinical studies of TCM therapies for all kinds of cancers published in Chinese in four main Chinese electronic databases from their inception to November 2011. They found a total of 2964 reports (involving 253,434 cancer patients) including 2385 randomized controlled trials and 579 non-randomized controlled studies.

The top seven cancer types treated were lung cancer, liver cancer, stomach cancer, breast cancer, esophagus cancer, colorectal cancer and nasopharyngeal cancer by both study numbers and case numbers. The majority of studies (72%) applied TCM therapy combined with conventional treatment, whilst fewer (28%) applied only TCM therapy in the experimental groups. Herbal medicine was the most frequently applied TCM therapy (2677 studies, 90.32%). The most frequently reported outcome was clinical symptom improvement (1667 studies, 56.24%) followed by biomarker indices (1270 studies, 42.85%), quality of life (1129 studies, 38.09%), chemo/radiotherapy induced side effects (1094 studies, 36.91%), tumour size (869 studies, 29.32%) and safety (547 studies, 18.45%).

The authors concluded that data from controlled clinical studies of TCM therapies in cancer treatment is substantial, and different therapies are applied either as monotherapy or in combination with conventional medicine. Reporting of controlled clinical studies should be improved based on the CONSORT and TREND Statements in future. Further studies should address the most frequently used TCM therapy for common cancers and outcome measures should address survival, relapse/metastasis and quality of life.

This paper is important, in my view, predominantly because it exemplifies the problem with TCM research from China and with uncritical reviews on this subject. If a cancer patient, who does not know the background, reads this paper, (s)he might think that TCM is worth trying. This conclusion could easily shorten his/her life.

The often-shown fact is that TCM studies from China are not reliable. They are almost invariably positive, their methodological quality is low, and they are frequently based on fabricated data. In my view, it is irresponsible to publish a review that omits discussing these facts in detail and issuing a stark warning.

TCM FOR CANCER IS A VERY BAD CHOICE!

I regularly scan the new publications in alternative medicine hoping that I find some good quality research. And sometimes I do! In such happy moments, I write a post and make sure that I stress the high standard of a paper.

Sadly, such events are rare. Usually, my searches locate a multitude of deplorably poor papers. Most of the time, I ignore them. Sometime, I do write about exemplarily bad science, and often I report about articles that are not just bad but dangerous as well. The following paper falls into this category, I fear.

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the efficacy and safety of herbal medicines for the induction of labor (IOL). The researchers considered experimental and non-experimental studies that compared relevant pregnancy outcomes between users and non-user of herbal medicines for IOL.

A total of 1421 papers were identified and 10 studies, including 5 RCTs met the authors’ inclusion criteria. Papers not published in English were not considered. Three trials were conducted in Iran, two in the USA and one each in South Africa, Israel, Thailand, Australia and Italy.

The quality of the included trial, even of the 5 RCTs, was poor. The results suggest, according to the authors of this paper, that users of herbal medicine – raspberry leaf and castor oil – for IOL were significantly more likely to give birth within 24 hours than non-users. No significant difference in the incidence of caesarean section, assisted vaginal delivery, haemorrhage, meconium-stained liquor and admission to nursery was found between users and non-users of herbal medicines for IOL.

The authors concluded that the findings suggest that herbal medicines for IOL are effective, but there is inconclusive evidence of safety due to lack of good quality data. Thus, the use of herbal medicines for IOL should be avoided until safety issues are clarified. More studies are recommended to establish the safety of herbal medicines.

As I stated above, I am not convinced that this review is any good. It included all sorts of study designs and dismissed papers that were not in English. Surely this approach can only generate a distorted or partial picture. The risks of herbal remedies for mother and baby are not well investigated. In view of the fact that even the 5 RCTs were of poor quality, the first sentence of this conclusion seems most inappropriate.

On the basis of the evidence presented, I feel compelled to urge pregnant women NOT to consent to accept herbal remedies for IOL.

And on the basis of the fact that far too many papers on alternative medicine that emerge every day are not just poor quality but also dangerously mislead the public, I urge publishers, editors, peer-reviewers and researchers to pause and remember that they all have a responsibility. This nonsense has been going on for long enough; it is high time to stop it.

Homeopathy for depression? A previous review concluded that the evidence for the effectiveness of homeopathy in depression is limited due to lack of clinical trials of high quality. But that was 13 years ago. Perhaps the evidence has changed?

A new review aimed to assess the efficacy, effectiveness and safety of homeopathy in depression. Eighteen studies assessing homeopathy in depression were included. Two double-blind placebo-controlled trials of homeopathic medicinal products (HMPs) for depression were assessed.

- The first trial (N = 91) with high risk of bias found HMPs were non-inferior to fluoxetine at 4 and 8 weeks.

- The second trial (N = 133), with low risk of bias, found HMPs was comparable to fluoxetine and superior to placebo at 6 weeks.

The remaining research had unclear/high risk of bias. A non-placebo-controlled RCT found standardised treatment by homeopaths comparable to fluvoxamine; a cohort study of patients receiving treatment provided by GPs practising homeopathy reported significantly lower consumption of psychotropic drugs and improved depression; and patient-reported outcomes showed at least moderate improvement in 10 of 12 uncontrolled studies. Fourteen trials provided safety data. All adverse events were mild or moderate, and transient. No evidence suggested treatment was unsafe.

The authors concluded that limited evidence from two placebo-controlled double-blinded trials suggests HMPs might be comparable to antidepressants and superior to placebo in depression, and patients treated by homeopaths report improvement in depression. Overall, the evidence gives a potentially promising risk benefit ratio. There is a need for additional high quality studies.

I beg to differ!

What these data really show amounts to far less than the authors imply:

- The two ‘double-blind’ trials are next to meaningless. As equivalence studies they were far too small to produce meaningful results. Any decent review should discuss this fact in full detail. Moreover, these studies cannot have been double-blind, because the typical adverse-effects of anti-depressants would have ‘de-blinded’ the trial participants. Therefore, these results are almost certainly false-positive.

- The other studies are even less rigorous and therefore do also not allow positive conclusions.

This review was authored by known proponents of homeopathy. It is, in my view, an exercise in promotion rather than a piece of research. I very much doubt that a decent journal with a responsible peer-review system would have ever published such a biased paper – it had to appear in the infamous EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE.

So what?

Who cares? No harm done!

Again, I beg to differ.

Why?

The conclusion that homeopathy has a ‘promising risk/benefit profile’ is frightfully dangerous and irresponsible. If seriously depressed patients follow it, many lives might be lost.

Yet again, we see that poor research has the potential to kill vulnerable individuals.

One theory as to how acupuncture works is that it increases endorphin levels in the brain. These ‘feel-good’ chemicals could theoretically be helpful for weaning alcohol-dependent people off alcohol. So, for once, we might have a (semi-) plausible mechanism as to how acupuncture could be clinically effective. But a ‘beautiful hypothesis’ does not necessarily mean acupuncture works for alcohol dependence. To answer this question, we need clinical trials or systematic reviews of clinical trials.

A new systematic review assessed the effects and safety of acupuncture for alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS). All RCTs of drug plus acupuncture or acupuncture alone for the treatment of AWS were included. Eleven RCTs with a total of 875 participants were included. In the acute phase, two trials reported no difference between drug plus acupuncture and drug plus sham acupuncture in the reduction of craving for alcohol; however, two positive trials reported that drug plus acupuncture was superior to drug alone in the alleviation of psychological symptoms. In the protracted phase, one trial reported acupuncture was superior to sham acupuncture in reducing the craving for alcohol, one trial reported no difference between acupuncture and drug (disulfiram), and one trial reported acupuncture was superior to sham acupuncture for the alleviation of psychological symptoms. Adverse effects were tolerable and not severe.

The authors concluded that there was no significant difference between acupuncture (plus drug) and sham acupuncture (plus drug) with respect to the primary outcome measure of craving for alcohol among participants with AWS, and no difference in completion rates (pooled results). There was limited evidence from individual trials that acupuncture may reduce alcohol craving in the protracted phase and help alleviate psychological symptoms; however, given concerns about the quantity and quality of included studies, further large-scale and well-conducted RCTs are needed.

There is little to add here. Perhaps just two short points:

1. The quality of the trials was poor; only one study of the 11 trials was of acceptable rigor. Here is its abstract:

We report clinical data on the efficacy of acupuncture for alcohol dependence. 503 patients whose primary substance of abuse was alcohol participated in this randomized, single blind, placebo controlled trial. Patients were assigned to either specific acupuncture, nonspecific acupuncture, symptom based acupuncture or convention treatment alone. Alcohol use was assessed, along with depression, anxiety, functional status, and preference for therapy. This article will focus on results pertaining to alcohol use. Significant improvement was shown on nearly all measures. There were few differences associated with treatment assignment and there were no treatment differences on alcohol use measures, although 49% of subjects reported acupuncture reduced their desire for alcohol. The placebo and preference for treatment measures did not materially effect the results. Generally, acupuncture was not found to make a significant contribution over and above that achieved by conventional treatment alone in reduction of alcohol use.

To me, this does not sound all that encouraging.

2. Of the 11 RCTs, 8 failed to report on adverse effects of acupuncture. In my book, this means these trials were in violation with basic research ethics.

My conclusion of all this: another ugly fact kills a beautiful hypothesis.

Homotoxicology is sometimes praised as the ‘best kept detox secret‘, often equated with homeopathy, and even more often not understood at all.

But what is it really?

Homotoxicology is the science of toxins and their removal from the human body. It offers a theory of disease which describes the severity and duration of an illness or disorder based on toxin-loading relative to our body’s ability to detoxify. In other words, it tells you how sick you’ll get when what stays inside progressively overwhelms our ability to get the garbage out. It explains what you can expect to see as you start removing toxins.

And yes, there is a hierarchy of toxic substances. Homotoxicology says you should remove the gentler ones first. As the body strengthens, it will be able to handle the really bad stuff (i.e., heavy metals). This explains why some people do really well on the same detox treatments that take others out at the knees.

Yes, I know!

This sounds very much like promotional BS!!!

So, what is it really, and what evidence is there to support it?

Homotoxicolgy is a therapy developed by the German physician and homeopath Hans Reckeweg. It is strongly influenced by (but not identical with) homoeopathy. Proponents of homotoxicology understand it as a modern extension of homoeopathy developed partly in response to the effects of the Industrial Revolution, which imposed chemical pollutants on the human body.

„Ich möchte einmal die Homöopathie mit der Schulmedizin verschmelzen H.-H. Reckeweg Küstermann/Auriculotherapie_2008.

According to the assumptions of homotoxicology, any human disease is the result of toxins, which originate either from within the body or from its environment. Allegedly, each disease process runs through six specific phases and is the expression of the body’s attempt to cope with these toxins. Diseases are thus viewed as biologically useful defence mechanisms. Health, on the other hand, is the expression of the absence of toxins in our body. It seems obvious that these assumptions are not based on science and bear no relationship to accepted principles of toxicology or therapeutics. In other words, homotoxicology is not plausible.

According to the assumptions of homotoxicology, any human disease is the result of toxins, which originate either from within the body or from its environment. Allegedly, each disease process runs through six specific phases and is the expression of the body’s attempt to cope with these toxins. Diseases are thus viewed as biologically useful defence mechanisms. Health, on the other hand, is the expression of the absence of toxins in our body. It seems obvious that these assumptions are not based on science and bear no relationship to accepted principles of toxicology or therapeutics. In other words, homotoxicology is not plausible.

The therapeutic strategies of homotoxicology are essentially threefold:

• prevention of further homotoxicological challenges,

• elimination of homotoxins,

• treatment of existing ‘homotoxicoses’.

Frequently used homotoxicological remedies are fixed combinations of homeopathically prepared remedies such as nosodes, suis-organ preparations and conventional drugs. All these remedies are diluted and potentised according to the rules of homoeopathy. Proponents of homotoxicology claim that they activate what Reckeweg called the ‘greater defence system’— a concerted neurological, endocrine, immunological, metabolic and connective tissue response that can give rise to symptoms and thus excretes homotoxins. Homotoxicological remedies are produced by Heel, Germany and are sold in over 60 countries. The crucial difference between homotoxicology and homoeopathy is that the latter follows the ‘like cures like’ principle, while the former does not. As this is the defining principle of homeopathy, it would be clearly wrong to assume that homotoxicology is a form of homeopathy.

Several clinical trials of homotoxicology are available. They are usually sponsored or conducted by the manufacturer. Independent research is very rare. In most major reviews, these studies are reviewed together with trials of homeopathic remedies which is obviously not correct. Our systematic review purely of studies of homotoxicology included 7 studies, all of which had major flaws. We concluded that the placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trials of homotoxicology fail to demonstrate the efficacy of this therapeutic approach.

So, I ask again: what is homotoxicology?

It is little more than homeopathic nonsense + detox nonsense + some more nonsense.

My advice is to say well clear of it.

Often referred to as “Psychological acupressure”, the emotional freedom technique (EFT) works by releasing blockages within the energy system which are the source of emotional intensity and discomfort. These blockages in our energy system, in addition to challenging us emotionally, often lead to limiting beliefs and behaviours and an inability to live life harmoniously. Resulting symptoms are either emotional and/ or physical and include lack of confidence and self esteem, feeling stuck anxious or depressed, or the emergence of compulsive and addictive behaviours. It is also now finally widely accepted that emotional disharmony is a key factor in physical symptoms and dis-ease and for this reason these techniques are being extensively used on physical issues, including chronic illness with often astounding results. As such these techniques are being accepted more and more in medical and psychiatric circles as well as in the range of psychotherapies and healing disciplines.

An EFT treatment involves the use of fingertips rather than needles to tap on the end points of energy meridians that are situated just beneath the surface of the skin. The treatment is non-invasive and works on the ethos of making change as simple and as pain free as possible.

EFT is a common sense approach that draws its power from Eastern discoveries that have been around for over 5,000 years. In fact Albert Einstein also told us back in the 1920’s that everything (including our bodies) is composed of energy. These ideas have been largely ignored by Western Healing Practices and as they are unveiled in our current times, human process is reopening itself to the forgotten truth that everything is Energy and the potential that this offers us.

END OF QUOTE

If you ask me, this sounds as though EFT combines pseudo-psychological with acupuncture-BS.

But I may be wrong.

What does the evidence tell us?

A systematic review included 14 RCTs of EFT with a total of 658 patients. The pre-post effect size for the EFT treatment group was 1.23 (95% confidence interval, 0.82-1.64; p < 0.001), whereas the effect size for combined controls was 0.41 (95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.67; p = 0.001). Emotional freedom technique treatment demonstrated a significant decrease in anxiety scores, even when accounting for the effect size of control treatment. However, there were too few data available comparing EFT to standard-of-care treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy, and further research is needed to establish the relative efficacy of EFT to established protocols. Meta-analyses indicate large effect sizes for posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety; however, treatment effects may be due to components EFT shares with other therapies.

Another, more recent analysis reviewed whether EFTs acupressure component was an active ingredient. Six studies of adults with diagnosed or self-identified psychological or physical symptoms were compared (n = 403), and three (n = 102) were identified. Pretest vs. posttest EFT treatment showed a large effect size, Cohen’s d = 1.28 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.56 to 2.00) and Hedges’ g = 1.25 (95% CI, 0.54 to 1.96). Acupressure groups demonstrated moderately stronger outcomes than controls, with weighted posttreatment effect sizes of d = -0.47 (95% CI, -0.94 to 0.0) and g = -0.45 (95% CI, -0.91 to 0.0). Meta-analysis indicated that the acupressure component was an active ingredient and outcomes were not due solely to placebo, nonspecific effects of any therapy, or non-acupressure components.

From these and other reviews, one could easily get the impression that my above-mentioned suspicion is erroneous and EFT is an effective therapy. But I still do have my doubts.

Why?

These reviews conveniently forget to mention that the primary studies tend to be of poor or even very poor quality. The most common flaws include tiny sample sizes, wrong statistical approach, lack of blinding, lack of control of placebo and other nonspecific effects. Reviews of such studies thus turn out to be a confirmation of the ‘rubbish in, rubbish out’ principle: any summary of flawed studies are likely to produce a flawed result.

Until I have good quality trials to convince me otherwise, EFT is in my view:

- implausible and

- not of proven effectiveness for any condition.

Fish oil (omega-3 PUFA) preparations are today extremely popular and amongst the best-researched dietary supplement. During the 1970s, two Danish scientists, Bang and Dyerberg, remarked that Greenland Eskimos had a baffling lower prevalence of coronary artery disease than mainland Danes. They also noted that their diet contained large amounts of seal and whale blubber and suggested that this ‘Eskimo-diet’ was a key factor in the lower prevalence. Subsequently, a flurry of research stared to investigate the phenomenon, and it was shown that the ‘Eskimo-diet’ contained unusually high concentrations of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from fish oils (seals and whales feed predominantly on fish).

Initial research also demonstrated that the regular consumption of fish oil has a multitude of cardiovascular and anti-inflammatory effects. This led to the promotion of fish oil supplements for a wide range of conditions. Meanwhile, many of these encouraging findings have been overturned by more rigorous studies, and the enthusiasm for fish oil supplements has somewhat waned. But now, a new paper has come out with surprising findings.

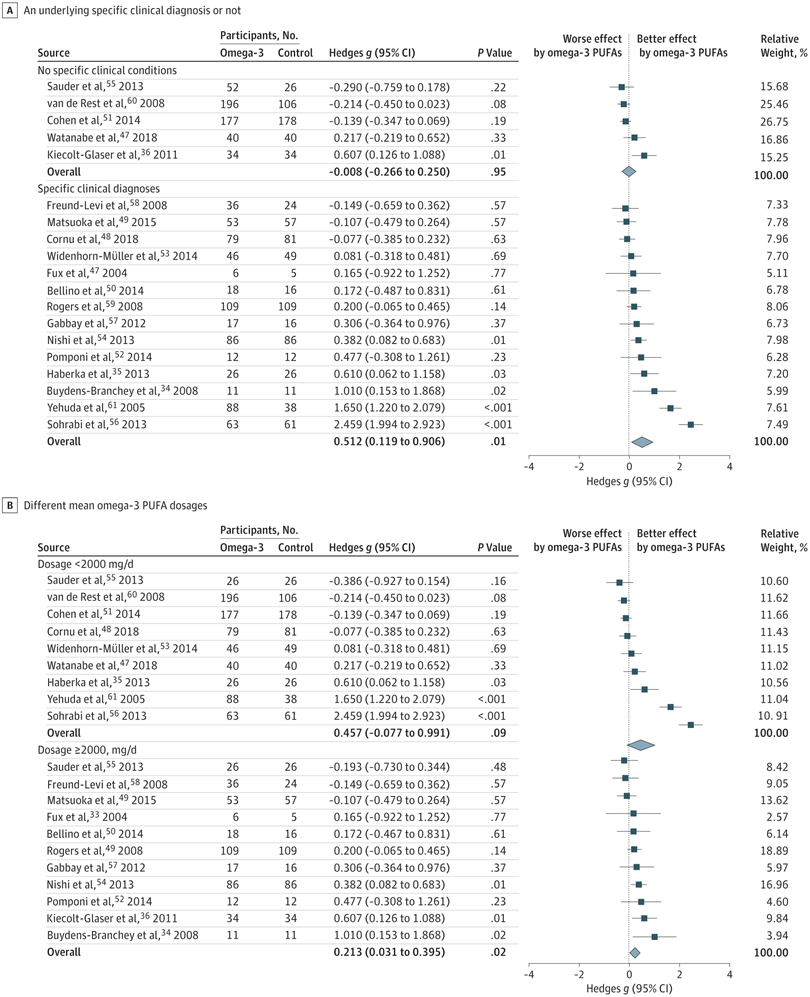

The objective of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the association of anxiety symptoms with omega-3 PUFA treatment compared with controls in varied populations.

A search was performed of clinical trials assessing the anxiolytic effect of omega-3 PUFAs in humans, in either placebo-controlled or non–placebo-controlled designs. Of 104 selected articles, 19 entered the final data extraction stage. Two authors independently extracted the data according to a predetermined list of interests. A random-effects model meta-analysis was performed. Changes in the severity of anxiety symptoms after omega-3 PUFA treatment served as the main endpoint.

In total, 1203 participants with omega-3 PUFA treatment and 1037 participants without omega-3 PUFA treatment showed an association between clinical anxiety symptoms among participants with omega-3 PUFA treatment compared with control arms. Subgroup analysis showed that the association of treatment with reduced anxiety symptoms was significantly greater in subgroups with specific clinical diagnoses than in subgroups without clinical conditions. The anxiolytic effect of omega-3 PUFAs was significantly better than that of controls only in subgroups with a higher dosage (at least 2000 mg/d) and not in subgroups with a lower dosage (<2000 mg/d).

The authors concluded that this review indicates that omega-3 PUFAs might help to reduce the symptoms of clinical anxiety. Further well-designed studies are needed in populations in whom anxiety is the main symptom.

I think this is a fine meta-analysis reporting clear results. I doubt that this paper truly falls under the umbrella of alternative medicine, but fish oil is a popular food supplement and should be mentioned on this blog. Of course, the average effect size is modest, but the findings are nevertheless intriguing.

I remember reading this paper entitled ‘Comparison of acupuncture and other drugs for chronic constipation: A network meta-analysis’ when it first came out. I considered discussing it on my blog, but then decided against it for a range of reasons which I shall explain below. The abstract of the original meta-analysis is copied below:

The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and side effects of acupuncture, sham acupuncture and drugs in the treatment of chronic constipation. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of acupuncture and drugs for chronic constipation were comprehensively retrieved from electronic databases (such as PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, CNKI, Wanfang Database, VIP Database and CBM) up to December 2017. Additional references were obtained from review articles. With quality evaluations and data extraction, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was performed using a random-effects model under a frequentist framework. A total of 40 studies (n = 11032) were included: 39 were high-quality studies and 1 was a low-quality study. NMA showed that (1) acupuncture improved the symptoms of chronic constipation more effectively than drugs; (2) the ranking of treatments in terms of efficacy in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome was acupuncture, polyethylene glycol, lactulose, linaclotide, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, prucalopride, sham acupuncture, tegaserod, and placebo; (3) the ranking of side effects were as follows: lactulose, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, polyethylene glycol, prucalopride, linaclotide, placebo and tegaserod; and (4) the most commonly used acupuncture point for chronic constipation was ST25. Acupuncture is more effective than drugs in improving chronic constipation and has the least side effects. In the future, large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to prove this. Sham acupuncture may have curative effects that are greater than the placebo effect. In the future, it is necessary to perform high-quality studies to support this finding. Polyethylene glycol also has acceptable curative effects with fewer side effects than other drugs.

END OF 1st QUOTE

This meta-analysis has now been retracted. Here is what the journal editors have to say about the retraction:

After publication of this article [1], concerns were raised about the scientific validity of the meta-analysis and whether it provided a rigorous and accurate assessment of published clinical studies on the efficacy of acupuncture or drug-based interventions for improving chronic constipation. The PLOS ONE Editors re-assessed the article in collaboration with a member of our Editorial Board and noted several concerns including the following:

- Acupuncture and related terms are not mentioned in the literature search terms, there are no listed inclusion or exclusion criteria related to acupuncture, and the outcome measures were not clearly defined in terms of reproducible clinical measures.

- The study included acupuncture and electroacupuncture studies, though this was not clearly discussed or reported in the Title, Methods, or Results.

- In the “Routine paired meta-analysis” section, both acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups were reported as showing improvement in symptoms compared with placebo. This finding and its implications for the conclusions of the article were not discussed clearly.

- Several included studies did not meet the reported inclusion criteria requiring that studies use adult participants and assess treatments of >2 weeks in duration.

- Data extraction errors were identified by comparing the dataset used in the meta-analysis (S1 Table) with details reported in the original research articles. Errors included aspects of the study design such as the experimental groups included in the study, the number of study arms in the trial, number of participants, and treatment duration. There are also several errors in the Reference list.

- With regard to side effects, 22 out of 40 studies were noted as having reported side effects. It was not made clear whether side effects were assessed as outcome measures for the other 18 studies, i.e. did the authors collect data clarifying that there were no side effects or was this outcome measure not assessed or reported in the original article. Without this clarification the conclusion comparing side effect frequencies is not well supported.

- The network geometry presented in Fig 5 is not correct and misrepresents some of the study designs, for example showing two-arm studies as three-arm studies.

- The overall results of the meta-analysis are strongly reliant on the evidence comparing acupuncture versus lactulose treatment. Several of the trials that assessed this comparison were poorly reported, and the meta-analysis dataset pertaining to these trials contained data extraction errors. Furthermore, potential bias in studies assessing lactulose efficacy in acupuncture trials versus lactulose efficacy in other trials was not sufficiently addressed.

While some of the above issues could be addressed with additional clarifications and corrections to the text, the concerns about study inclusion, the accuracy with which the primary studies’ research designs and data were represented in the meta-analysis, and the reporting quality of included studies directly impact the validity and accuracy of the dataset underlying the meta-analysis. As a consequence, we consider that the overall conclusions of the study are not reliable. In light of these issues, the PLOS ONE Editors retract the article. We apologize that these issues were not adequately addressed during pre-publication peer review.

LZ disagreed with the retraction. YM and XD did not respond.

END OF 2nd QUOTE

Let me start by explaining why I initially decided not to discuss this paper on my blog. Already the first sentence of the abstract put me off, and an entire chorus of alarm-bells started ringing once I read further.

- A meta-analysis is not a ‘study’ in my book, and I am somewhat weary of researchers who employ odd or unprecise language.

- We all know (and I have discussed it repeatedly) that studies of acupuncture frequently fail to report adverse effects (in doing this, their authors violate research ethics!). So, how can it be a credible aim of a meta-analysis to compare side-effects in the absence of adequate reporting?

- The methodology of a network meta-analysis is complex and I know not a lot about it.

- Several things seemed ‘too good to be true’, for instance, the funnel-plot and the overall finding that acupuncture is the best of all therapeutic options.

- Looking at the references, I quickly confirmed my suspicion that most of the primary studies were in Chinese.

In retrospect, I am glad I did not tackle the task of criticising this paper; I would probably have made not nearly such a good job of it as PLOS ONE eventually did. But it was only after someone raised concerns that the paper was re-reviewed and all the defects outlined above came to light.

While some of my concerns listed above may have been trivial, my last point is the one that troubles me a lot. As it also related to dozens of Cochrane reviews which currently come out of China, it is worth our attention, I think. The problem, as I see it, is as follows:

- Chinese (acupuncture, TCM and perhaps also other) trials are almost invariably reporting positive findings, as we have discussed ad nauseam on this blog.

- Data fabrication seems to be rife in China.

- This means that there is good reason to be suspicious of such trials.

- Many of the reviews that currently flood the literature are based predominantly on primary studies published in Chinese.

- Unless one is able to read Chinese, there is no way of evaluating these papers.

- Therefore reviewers of journal submissions tend to rely on what the Chinese review authors write about the primary studies.

- As data fabrication seems to be rife in China, this trust might often not be justified.

- At the same time, Chinese researchers are VERY keen to publish in top Western journals (this is considered a great boost to their career).

- The consequence of all this is that reviews of this nature might be misleading, even if they are published in top journals.

I have been struggling with this problem for many years and have tried my best to alert people to it. However, it does not seem that my efforts had even the slightest success. The stream of such reviews has only increased and is now a true worry (at least for me). My suspicion – and I stress that it is merely that – is that, if one would rigorously re-evaluate these reviews, their majority would need to be retracted just as the above paper. That would mean that hundreds of papers would disappear because they are misleading, a thought that should give everyone interested in reliable evidence sleepless nights!

So, what can be done?

Personally, I now distrust all of these papers, but I admit, that is not a good, constructive solution. It would be better if Journal editors (including, of course, those at the Cochrane Collaboration) would allocate such submissions to reviewers who:

- are demonstrably able to conduct a CRITICAL analysis of the paper in question,

- can read Chinese,

- have no conflicts of interest.

In the case of an acupuncture review, this would narrow it down to perhaps just a handful of experts worldwide. This probably means that my suggestion is simply not feasible.

But what other choice do we have?

One could oblige the authors of all submissions to include full and authorised English translations of non-English articles. I think this might work, but it is, of course, tedious and expensive. In view of the size of the problem (I estimate that there must be around 1 000 reviews out there to which the problem applies), I do not see a better solution.

(I would truly be thankful, if someone had a better one and would tell us)

Psoriasis is one of those conditions that is

- chronic,

- not curable,

- irritating to the point where it reduces quality of life.

In other words, it is a disease for which virtually all alternative treatments on the planet are claimed to be effective. But which therapies do demonstrably alleviate the symptoms?

This review (published in JAMA Dermatology) compiled the evidence on the efficacy of the most studied complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities for treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis and discusses those therapies with the most robust available evidence.

PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov searches (1950-2017) were used to identify all documented CAM psoriasis interventions in the literature. The criteria were further refined to focus on those treatments identified in the first step that had the highest level of evidence for plaque psoriasis with more than one randomized clinical trial (RCT) supporting their use. This excluded therapies lacking RCT data or showing consistent inefficacy.

A total of 457 articles were found, of which 107 articles were retrieved for closer examination. Of those articles, 54 were excluded because the CAM therapy did not have more than 1 RCT on the subject or showed consistent lack of efficacy. An additional 7 articles were found using references of the included studies, resulting in a total of 44 RCTs (17 double-blind, 13 single-blind, and 14 nonblind), 10 uncontrolled trials, 2 open-label nonrandomized controlled trials, 1 prospective controlled trial, and 3 meta-analyses.

Compared with placebo, application of topical indigo naturalis, studied in 5 RCTs with 215 participants, showed significant improvements in the treatment of psoriasis. Treatment with curcumin, examined in 3 RCTs (with a total of 118 participants), 1 nonrandomized controlled study, and 1 uncontrolled study, conferred statistically and clinically significant improvements in psoriasis plaques. Fish oil treatment was evaluated in 20 studies (12 RCTs, 1 open-label nonrandomized controlled trial, and 7 uncontrolled studies); most of the RCTs showed no significant improvement in psoriasis, whereas most of the uncontrolled studies showed benefit when fish oil was used daily. Meditation and guided imagery therapies were studied in 3 single-blind RCTs (with a total of 112 patients) and showed modest efficacy in treatment of psoriasis. One meta-analysis of 13 RCTs examined the association of acupuncture with improvement in psoriasis and showed significant improvement with acupuncture compared with placebo.

The authors concluded that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis are indigo naturalis, curcumin, dietary modification, fish oil, meditation, and acupuncture. This review will aid practitioners in advising patients seeking unconventional approaches for treatment of psoriasis.

I am sorry to say so, but this review smells fishy! And not just because of the fish oil. But the fish oil data are a good case in point: the authors found 12 RCTs of fish oil. These details are provided by the review authors in relation to oral fish oil trials: Two double-blind RCTs (one of which evaluated EPA, 1.8g, and DHA, 1.2g, consumed daily for 12 weeks, and the other evaluated EPA, 3.6g, and DHA, 2.4g, consumed daily for 15 weeks) found evidence supporting the use of oral fish oil. One open-label RCT and 1 open-label non-randomized controlled trial also showed statistically significant benefit. Seven other RCTs found lack of efficacy for daily EPA (216mgto5.4g)or DHA (132mgto3.6g) treatment. The remainder of the data supporting efficacy of oral fish oil treatment were based on uncontrolled trials, of which 6 of the 7 studies found significant benefit of oral fish oil. This seems to support their conclusion. However, the authors also state that fish oil was not shown to be effective at several examined doses and duration. Confused? Yes, me too!

Even more confusing is their failure to mention a single trial of Mahonia aquifolium. A 2013 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Dermatology included 5 RCTs of Mahonia aquifolium which, according to these authors, provided ‘limited support’ for its effectiveness. How could they miss that?

More importantly, how could the reviewers miss to conduct a proper evaluation of the quality of the studies they included in their review (even in their abstract, they twice speak of ‘robust evidence’ – but how can they without assessing its robustness? [quantity is not remotely the same as quality!!!]). Without a transparent evaluation of the rigour of the primary studies, any review is nearly worthless.

Take the 12 acupuncture trials, for instance, which the review authors included based not on an assessment of the studies but on a dodgy review published in a dodgy journal. Had they critically assessed the quality of the primary studies, they could have not stated that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis …[include]… acupuncture. Instead they would have had to admit that these studies are too dubious for any firm conclusion. Had they even bothered to read them, they would have found that many are in Chinese (which would have meant they had to be excluded in their review [as many pseudo-systematic reviewers, the authors only considered English papers]).

There might be a lesson in all this – well, actually I can think of at least two:

- Systematic reviews might well be the ‘Rolls Royce’ of clinical evidence. But even a Rolls Royce needs to be assembled correctly, otherwise it is just a heap of useless material.

- Even top journals do occasionally publish poor-quality and thus misleading reviews.

The aim of palliative care is to improve quality of life for patients with serious illnesses by treating their symptoms, often in situations where all the possible causative therapeutic options have been exhausted. In many palliative care settings, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is used for this purpose. In fact, this is putting it mildly; my impression is that CAM seems to have flooded palliative care. The question is therefore whether this approach is based on sufficiently good evidence.

This review was aimed at evaluating the available evidence on the use of CAM in hospice and palliative care and to summarize their potential benefits. The researchers conducted thorough literature searches and located 4682 studies of which 17 were identified for further evaluation. The therapies considered included:

- acupressure,

- acupuncture,

- aromatherapy massage,

- breathing,

- hypnotherapy,

- massage,

- meditation,

- music therapy,

- reflexology,

- reiki.

Many studies demonstrated a short-term benefit in symptom improvement from baseline with CAM, although a significant benefit was not found between groups.

The authors concluded that CAM may provide a limited short-term benefit in patients with symptom burden. Additional studies are needed to clarify the potential value of CAM in the hospice or palliative setting.

When reading research articles in CAM, I often have to ask myself: ARE THEY TAKING THE MIKEY?

??? “Many studies demonstrated a short-term benefit in symptom improvement from baseline with CAM, although a significant benefit was not found between groups.” ???

Really?!?!?

Controlled clinical trials are only about comparing the outcomes between the experimental and the control groups (and not about assessing improvements from baseline which can be [and often is] unrelated to any effect caused by the treatment per se). Therefore, within-group changes are irrelevant and should not even deserve a mention in the abstract. Thus the only finding worth reporting in the abstract is this:

No significant benefit was found.

It follows that the above conclusions are totally out of line with the data.

They should, according to what the researchers report in their abstract, read something like this:

CAM HAS NO PROVEN BENEFIT IN PALLIATIVE CARE. ITS USE IN THIS AREA IS THEREFORE HIGHLY PROBLEMATIC.