symptom-relief

This single-blind, randomized, clinical trial was aimed at determining the long-term clinical effects of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) or mobilization (MOB) as an adjunct to neurodynamic mobilization (NM) in the management of individuals with Lumbar Disc Herniation with Radiculopathy (DHR).

Forty participants diagnosed as having a chronic DHR (≥3 months) were randomly allocated into two groups with 20 participants each in the SMT and MOB groups.

Participants in the SMT group received high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation, while those in the MOB group received Mulligans’ spinal mobilization with leg movement. Each treatment group also received NM as a co-intervention, administered immediately after the SMT and MOB treatment sessions. Each group received treatment twice a week for 12 weeks.

The following outcomes were measured at baseline, 6, 12, 26, and 52 weeks post-randomization; back pain, leg pain, activity limitation, sciatica bothersomeness, sciatica frequency, functional mobility, quality of life, and global effect. The primary outcomes were pain and activity limitation at 12 weeks post-randomization.

The results indicate that the MOB group improved significantly better than the SMT group in all outcomes (p < 0.05), and at all timelines (6, 12, 26, and 52 weeks post-randomization), except for sensory deficit at 52 weeks, and reflex and motor deficits at 12 and 52 weeks. These improvements were also clinically meaningful for neurodynamic testing and sensory deficits at 12 weeks, back pain intensity at 6 weeks, and for activity limitation, functional mobility, and quality of life outcomes at 6, 12, 26, and 52 weeks of follow-ups. The risk of being improved at 12 weeks post-randomization was 40% lower (RR = 0.6, CI = 0.4 to 0.9, p = 0.007) in the SMT group compared to the MOB group.

The authors concluded that this study found that individuals with DHR demonstrated better improvements when treated with MOB plus NM than when treated with SMT plus NM. These improvements were also clinically meaningful for activity limitation, functional mobility, and quality of life outcomes at long-term follow-up.

Yet again, I find it hard to resist playing the devil’s advocate: had the researchers added a third group with sham-MOB, they would have perhaps found that this group would have recovered even faster. In other words, this study might show that SMT is no good for DHR (which I find unsurprising), but it does NOT demonstrate MOB to be an effective therapy.

Low back pain (LBP) affects almost all of us at some stage. It is so common that it has become one of the most important indications for most forms of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). In the discussions about the value (or otherwise) of SCAMs for LBP, we sometimes forget that there are many conventional medical options to treat LBP. It is therefore highly relevant to ask how effective they are. This overview aimed to summarise the evidence from Cochrane Reviews of the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of systemic pharmacological interventions for adults with non‐specific LBP.

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was searched from inception to 3 June 2021, to identify reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated systemic pharmacological interventions for adults with non‐specific LBP. Two authors independently assessed eligibility, extracted data, and assessed the quality of the reviews and certainty of the evidence using the AMSTAR 2 and GRADE tools. The review focused on placebo comparisons and the main outcomes were pain intensity, function, and safety.

Seven Cochrane Reviews that included 103 studies (22,238 participants) were included. There was high confidence in the findings of five reviews, moderate confidence in one, and low confidence in the findings of another. The reviews reported data on six medicines or medicine classes: paracetamol, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, opioids, and antidepressants. Three reviews included participants with acute or sub‐acute LBP and five reviews included participants with chronic LBP.

Acute LBP

Paracetamol

There was high‐certainty evidence for no evidence of difference between paracetamol and placebo for reducing pain intensity (MD 0.49 on a 0 to 100 scale (higher scores indicate worse pain), 95% CI ‐1.99 to 2.97), reducing disability (MD 0.05 on a 0 to 24 scale (higher scores indicate worse disability), 95% CI ‐0.50 to 0.60), and increasing the risk of adverse events (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.33).

NSAIDs

There was moderate‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring NSAIDs compared to placebo at reducing pain intensity (MD ‐7.29 on a 0 to 100 scale (higher scores indicate worse pain), 95% CI ‐10.98 to ‐3.61), high‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference for reducing disability (MD ‐2.02 on a 0‐24 scale (higher scores indicate worse disability), 95% CI ‐2.89 to ‐1.15), and very low‐certainty evidence for no evidence of an increased risk of adverse events (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0. 63 to 1.18).

Muscle relaxants and benzodiazepines

There was moderate‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring muscle relaxants compared to placebo for a higher chance of pain relief (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.76), and higher chance of improving physical function (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.77), and increased risk of adverse events (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1. 14 to 1.98).

Opioids

None of the included Cochrane Reviews aimed to identify evidence for acute LBP.

Antidepressants

No evidence was identified by the included reviews for acute LBP.

Chronic LBP

Paracetamol

No evidence was identified by the included reviews for chronic LBP.

NSAIDs

There was low‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring NSAIDs compared to placebo for reducing pain intensity (MD ‐6.97 on a 0 to 100 scale (higher scores indicate worse pain), 95% CI ‐10.74 to ‐3.19), reducing disability (MD ‐0.85 on a 0‐24 scale (higher scores indicate worse disability), 95% CI ‐1.30 to ‐0.40), and no evidence of an increased risk of adverse events (RR 1.04, 95% CI ‐0.92 to 1.17), all at intermediate‐term follow‐up (> 3 months and ≤ 12 months postintervention).

Muscle relaxants and benzodiazepines

There was low‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring benzodiazepines compared to placebo for a higher chance of pain relief (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.93), and low‐certainty evidence for no evidence of difference between muscle relaxants and placebo in the risk of adverse events (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.57).

Opioids

There was high‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring tapentadol compared to placebo at reducing pain intensity (MD ‐8.00 on a 0 to 100 scale (higher scores indicate worse pain), 95% CI ‐1.22 to ‐0.38), moderate‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring strong opioids for reducing pain intensity (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.52 to ‐0.33), low‐certainty evidence for a medium between‐group difference favouring tramadol for reducing pain intensity (SMD ‐0.55, 95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.44) and very low‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring buprenorphine for reducing pain intensity (SMD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐0.57 to ‐0.26).

There was moderate‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring strong opioids compared to placebo for reducing disability (SMD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.15), moderate‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring tramadol for reducing disability (SMD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.29 to ‐0.07), and low‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference favouring buprenorphine for reducing disability (SMD ‐0.14, 95% CI ‐0.53 to ‐0.25).

There was low‐certainty evidence for a small between‐group difference for an increased risk of adverse events for opioids (all types) compared to placebo; nausea (RD 0.10, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.14), headaches (RD 0.03, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.05), constipation (RD 0.07, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.11), and dizziness (RD 0.08, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.11).

Antidepressants

There was low‐certainty evidence for no evidence of difference for antidepressants (all types) compared to placebo for reducing pain intensity (SMD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.17) and reducing disability (SMD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.29).

The authors concluded as follows: we found no high‐ or moderate‐certainty evidence that any investigated pharmacological intervention provided a large or medium effect on pain intensity for acute or chronic LBP compared to placebo. For acute LBP, we found moderate‐certainty evidence that NSAIDs and muscle relaxants may provide a small effect on pain, and high‐certainty evidence for no evidence of difference between paracetamol and placebo. For safety, we found very low‐ and high‐certainty evidence for no evidence of difference with NSAIDs and paracetamol compared to placebo for the risk of adverse events, and moderate‐certainty evidence that muscle relaxants may increase the risk of adverse events. For chronic LBP, we found low‐certainty evidence that NSAIDs and very low‐ to high‐certainty evidence that opioids may provide a small effect on pain. For safety, we found low‐certainty evidence for no evidence of difference between NSAIDs and placebo for the risk of adverse events, and low‐certainty evidence that opioids may increase the risk of adverse events.

This is an important overview, in my opinion. It confirms what I and others have been stating for decades: WE CURRENTLY HAVE NO IDEAL SOLUTION TO LBP.

This is regrettable but true. It begs the question of what one should recommend to LBP sufferers. Here too, I have to repeat myself: (apart from staying as active as possible) the optimal therapy is the one that has the most favourable risk/benefit profile (and does not cost a fortune). And this option is not drugs, chiropractic, osteopathy, acupuncture, or any other SCAM – it is (physio)therapeutic exercise which is cheap, safe, and (mildly) effective.

Guided imagery is said to distract patients from disturbing feelings and thoughts, positively affects emotional well-being, and reduce pain by producing pleasing mental images.

This study aimed to determine the effects of guided imagery on postoperative pain management in patients undergoing lower extremity surgery. This randomized controlled study was conducted between April 2018 and May 2019. It included 60 patients who underwent lower extremity surgery. After using guided imagery, the posttest mean Visual Analog Scale score of patients in the intervention group was found to be 2.56 (1.00 ± 6.00), whereas the posttest mean score of patients in the control group was 4.10 (3.00 ± 6.00), and the difference between the groups was statistically significant (p <.001).

The authors concluded that guided imagery reduces short-term postoperative pain after lower extremity surgery.

I did not want to spend $52 to access the full article. Therefore, I can only comment on what the abstract tells me – and that is regrettably not a lot.

In fact, we don’t even learn what treatment was given to the control group. I guess that both groups receive standard post-op care and the control group received nothing in addition. This would mean that the observed effect might be entirely due to placebo and other non-specific effects. If that is so, the authors’ conclusion is not accurate.

I happen to think that guided imagery is a promising albeit under-researched therapy. Therefore, I am particularly frustrated to see that the few trials that do emerge of this option are woefully inadequate to determine its value.

Sure, the LP is dangerous nonsense, but this begs the question of whether so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) has anything to offer for patients suffering from ME/CFS. If the LP story tells us anything, then it must be this: we should not trust single trials, particularly if they seem dodgy. In other words, we should look at systematic reviews that synthesize ALL clinical trials and evaluate them critically.

To locate this type of evidence I conducted several Medline searches and found several recent systematic reviews that address the issue:

Context: A variety of interventions have been used in the treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Currently, debate exists among health care professionals and patients about appropriate strategies for management.

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of all interventions that have been evaluated for use in the treatment or management of CFS in adults or children.

Data sources: Nineteen specialist databases were searched from inception to either January or July 2000 for published or unpublished studies in any language. The search was updated through October 2000 using PubMed. Other sources included scanning citations, Internet searching, contacting experts, and online requests for articles.

Study selection: Controlled trials (randomized or nonrandomized) that evaluated interventions in patients diagnosed as having CFS according to any criteria were included. Study inclusion was assessed independently by 2 reviewers. Of 350 studies initially identified, 44 met inclusion criteria, including 36 randomized controlled trials and 8 controlled trials.

Data extraction: Data extraction was conducted by 1 reviewer and checked by a second. Validity assessment was carried out by 2 reviewers with disagreements resolved by consensus. A qualitative synthesis was carried out and studies were grouped according to type of intervention and outcomes assessed.

Data synthesis: The number of participants included in each trial ranged from 12 to 326, with a total of 2801 participants included in the 44 trials combined. Across the studies, 38 different outcomes were evaluated using about 130 different scales or types of measurement. Studies were grouped into 6 different categories. In the behavioral category, graded exercise therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy showed positive results and also scored highly on the validity assessment. In the immunological category, both immunoglobulin and hydrocortisone showed some limited effects but, overall, the evidence was inconclusive. There was insufficient evidence about effectiveness in the other 4 categories (pharmacological, supplements, complementary/alternative, and other interventions).

Conclusions: Overall, the interventions demonstrated mixed results in terms of effectiveness. All conclusions about effectiveness should be considered together with the methodological inadequacies of the studies. Interventions which have shown promising results include cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise therapy. Further research into these and other treatments is required using standardized outcome measures.

Introduction: Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) affects between 0.006% and 3% of the population depending on the criteria of definition used, with women being at higher risk than men.

Methods and outcomes: We conducted a systematic review and aimed to answer the following clinical question: What are the effects of treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome? We searched: Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library, and other important databases up to March 2010 (Clinical Evidence reviews are updated periodically; please check our website for the most up-to-date version of this review). We included harms alerts from relevant organisations such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Results: We found 46 systematic reviews, RCTs, or observational studies that met our inclusion criteria. We performed a GRADE evaluation of the quality of evidence for interventions.

Conclusions: In this systematic review we present information relating to the effectiveness and safety of the following interventions: antidepressants, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), corticosteroids, dietary supplements, evening primrose oil, galantamine, graded exercise therapy, homeopathy, immunotherapy, intramuscular magnesium, oral nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and prolonged rest.

Background: Throughout the world, patients with chronic diseases/illnesses use complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). The use of CAM is also substantial among patients with diseases/illnesses of unknown aetiology. Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also termed myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), is no exception. Hence, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials of CAM treatments in patients with CFS/ME was undertaken to summarise the existing evidence from RCTs of CAM treatments in this patient population.

Methods: Seventeen data sources were searched up to 13th August 2011. All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any type of CAM therapy used for treating CFS were included, with the exception of acupuncture and complex herbal medicines; studies were included regardless of blinding. Controlled clinical trials, uncontrolled observational studies, and case studies were excluded.

Results: A total of 26 RCTs, which included 3,273 participants, met our inclusion criteria. The CAM therapy from the RCTs included the following: mind-body medicine, distant healing, massage, tuina and tai chi, homeopathy, ginseng, and dietary supplementation. Studies of qigong, massage and tuina were demonstrated to have positive effects, whereas distant healing failed to do so. Compared with placebo, homeopathy also had insufficient evidence of symptom improvement in CFS. Seventeen studies tested supplements for CFS. Most of the supplements failed to show beneficial effects for CFS, with the exception of NADH and magnesium.

Conclusions: The results of our systematic review provide limited evidence for the effectiveness of CAM therapy in relieving symptoms of CFS. However, we are not able to draw firm conclusions concerning CAM therapy for CFS due to the limited number of RCTs for each therapy, the small sample size of each study and the high risk of bias in these trials. Further rigorous RCTs that focus on promising CAM therapies are warranted.

Background: There is no curative treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is widely used in the treatment of CFS in China.

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of TCM for CFS.

Methods: The protocol of this review is registered at PROSPERO. We searched six main databases for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on TCM for CFS from their inception to September 2013. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to assess the methodological quality. We used RevMan 5.1 to synthesize the results.

Results: 23 RCTs involving 1776 participants were identified. The risk of bias of the included studies was high. The types of TCM interventions varied, including Chinese herbal medicine, acupuncture, qigong, moxibustion, and acupoint application. The results of meta-analyses and several individual studies showed that TCM alone or in combination with other interventions significantly alleviated fatigue symptoms as measured by Chalder’s fatigue scale, fatigue severity scale, fatigue assessment instrument by Joseph E. Schwartz, Bell’s fatigue scale, and guiding principle of clinical research on new drugs of TCM for fatigue symptom. There was no enough evidence that TCM could improve the quality of life for CFS patients. The included studies did not report serious adverse events.

Conclusions: TCM appears to be effective to alleviate the fatigue symptom for people with CFS. However, due to the high risk of bias of the included studies, larger, well-designed studies are needed to confirm the potential benefit in the future.

Background: As the etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is unclear and the treatment is still a big issue. There exists a wide range of literature about acupuncture and moxibustion (AM) for CFS in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). But there are certain doubts as well in the effectiveness of its treatment due to the lack of a comprehensive and evidence-based medical proof to dispel the misgivings. Current study evaluated systematically the effectiveness of acupuncture and moxibustion treatments on CFS, and clarified the difference among them and Chinese herbal medicine, western medicine and sham-acupuncture.

Methods: We comprehensively reviewed literature including PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CBM (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database) and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) up to May 2016, for RCT clinical research on CFS treated by acupuncture and moxibustion. Traditional direct meta-analysis was adopted to analyze the difference between AM and other treatments. Analysis was performed based on the treatment in experiment and control groups. Network meta-analysis was adopted to make comprehensive comparisons between any two kinds of treatments. The primary outcome was total effective rate, while relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used as the final pooled statistics.

Results: A total of 31 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were enrolled in analyses. In traditional direct meta-analysis, we found that in comparison to Chinese herbal medicine, CbAM (combined acupuncture and moxibustion, which meant two or more types of acupuncture and moxibustion were adopted) had a higher total effective rate (RR (95% CI), 1.17 (1.09 ~ 1.25)). Compared with Chinese herbal medicine, western medicine and sham-acupuncture, SAM (single acupuncture or single moxibustion) had a higher total effective rate, with RR (95% CI) of 1.22 (1.14 ~ 1.30), 1.51 (1.31-1.74), 5.90 (3.64-9.56). In addition, compared with SAM, CbAM had a higher total effective rate (RR (95% CI), 1.23 (1.12 ~ 1.36)). In network meta-analyses, similar results were recorded. Subsequently, we ranked all treatments from high to low effective rate and the order was CbAM, SAM, Chinese herbal medicine, western medicine and sham-acupuncture.

Conclusions: In the treatment of CFS, CbAM and SAM may have better effect than other treatments. However, the included trials have relatively poor quality, hence high quality studies are needed to confirm our finding.

Objectives: This meta-analysis aimed to assess the effectiveness and safety of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) in treating chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Methods: Nine electronic databases were searched from inception to May 2022. Two reviewers screened studies, extracted the data, and assessed the risk of bias independently. The meta-analysis was performed using the Stata 12.0 software. Results: Eighty-four RCTs that explored the efficacy of 69 kinds of Chinese herbal formulas with various dosage forms (decoction, granule, oral liquid, pill, ointment, capsule, and herbal porridge), involving 6,944 participants were identified. This meta-analysis showed that the application of CHM for CFS can decrease Fatigue Scale scores (WMD: -1.77; 95%CI: -1.96 to -1.57; p < 0.001), Fatigue Assessment Instrument scores (WMD: -15.75; 95%CI: -26.89 to -4.61; p < 0.01), Self-Rating Scale of mental state scores (WMD: -9.72; 95%CI:-12.26 to -7.18; p < 0.001), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale scores (WMD: -7.07; 95%CI: -9.96 to -4.19; p < 0.001), Self-Rating Depression Scale scores (WMD: -5.45; 95%CI: -6.82 to -4.08; p < 0.001), and clinical symptom scores (WMD: -5.37; 95%CI: -6.13 to -4.60; p < 0.001) and improve IGA (WMD: 0.30; 95%CI: 0.20-0.41; p < 0.001), IGG (WMD: 1.74; 95%CI: 0.87-2.62; p < 0.001), IGM (WMD: 0.21; 95%CI: 0.14-0.29; p < 0.001), and the effective rate (RR = 1.41; 95%CI: 1.33-1.49; p < 0.001). However, natural killer cell levels did not change significantly. The included studies did not report any serious adverse events. In addition, the methodology quality of the included RCTs was generally not high. Conclusion: Our study showed that CHM seems to be effective and safe in the treatment of CFS. However, given the poor quality of reports from these studies, the results should be interpreted cautiously. More international multi-centered, double-blinded, well-designed, randomized controlled trials are needed in future research.

What does all that tell us?

Disappointingly, it tells me that SCAM has preciously little to offer for ME/CFS patients.

But what about the TCM treatments? Aren’t the above reviews quite positive TCM?

Yes, they are but I nevertheless recommend taking them with a healthy pinch of salt.

Why?

Because we have seen many times before that, for a range of reasons, Chinese researchers of TCM draw false positive conclusions. That may sound unfair, harsh, or even racist, but I think it’s true. If you disagree, please show me a couple of systematic reviews of TCM for any human disease by Chinese researchers that have drawn negative conclusions.

And what is my advice to patients suffering from ME/CSF?

I think the best I can offer is this: be very cautious about the many claims made by SCAM enthusiasts; if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is!

Cervical spondylosis (CS) is a general term for wear and tear affecting the spinal disks in the neck. As these disks age, they shrink and signs of osteoarthritis can develop, including bony projections along the edges of bones (bone spurs). CS is very common and worsens with age. About 85% of people over 60 are affected by cervical spondylosis. For most of them, it causes no symptoms. When symptoms do occur, non-surgical treatments often are effective. I think there are not many so-called alternative treatments that are not being promoted as effective for CS – often with the support of some lousy clinical trials. Homeopathy does not seem to be an exception.

This trial attempted evaluating the efficacy of individualized homeopathic medicines (IHMs) against placebos in the treatment of CS.

A 3-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at the Organon of Medicine outpatient department of the National Institute of Homoeopathy, India. Patients were randomized to receive either IHMs (n = 70) or identical-looking placebos (n = 70) in the mutual context of concomitant conservative and standard physiotherapeutic care. Primary outcome measures were 0-10 Numeric Rating Scales (NRSs) for pain, stiffness, numbness, tingling, weakness, and vertigo, and the secondary outcome was the Neck Disability Index (NDI), measured at baseline and every month until 3 months. The intention-to-treat sample was analyzed to detect group differences and effect sizes.

Overall, improvements were clinically significant and higher in the IHM group than in the placebo group, but group differences were statistically nonsignificant with small effect sizes (all p > 0.05, two-way repeated measure analysis of variance). After 2 months of time points, improvements observed in the IHM group were significantly higher than placebo on a few occasions (e.g., pain NRS: p < 0.001; stiffness NRS: p = 0.024; weakness NRS: p = 0.003). Sulfur (n = 21; 15%) was the most frequently prescribed medication. No harm, unintended effects, or any serious adverse events were reported from either group.

The authors concluded that an encouraging but nonsignificant direction of effect was elicited favoring IHMs against placebos in the treatment of CS.

I agree that it is encouraging that Indian homeopaths have recently dared to publish also negative findings! However, I do not agree that the findings are encouraging in the sense that they indicate anything other than that homeopathy is a placebo therapy.

Unfortunately, I cannot access the full article without paying for it. Thus I am unable to provide detailed criticism of this study – sorry.

Cervical radiculopathy is a common condition that is usually due to compression or injury to a nerve root by a herniated disc or other degenerative changes of the upper spine. The C5 to T1 levels are the most commonly affected. In such cases local and radiating pains, often with neurological deficits, are the most prominent symptoms. Treatment of this condition is often difficult.

The purpose of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness and safety of conservative interventions compared with other interventions, placebo/sham interventions, or no intervention on disability, pain, function, quality of life, and psychological impact in adults with cervical radiculopathy (CR).

MEDLINE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO were searched from inception to June 15, 2022, to identify studies that were randomized clinical trials, had at least one conservative treatment arm, and diagnosed participants with CR through confirmatory clinical examination and/or diagnostic tests. Studies were appraised using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool and the quality of the evidence was rated using the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach.

Of the 2561 records identified, 59 trials met our inclusion criteria (n = 4108 participants). Due to clinical and statistical heterogeneity, the findings were synthesized narratively. The results show very-low certainty evidence supporting the use of

- acupuncture,

- prednisolone,

- cervical manipulation,

- low-level laser therapy

for pain and disability in the immediate to short-term, and thoracic manipulation and low-level laser therapy for improvements in cervical range of motion in the immediate term.

There is low to very-low certainty evidence for multimodal interventions, providing inconclusive evidence for pain, disability, and range of motion. There is inconclusive evidence for pain reduction after conservative management compared with surgery, rated as very-low certainty.

The authors concluded that there is a lack of high-quality evidence, limiting our ability to make any meaningful conclusions. As the number of people with CR is expected to increase, there is an urgent need for future research to help address these gaps.

The fact that we cannot offer a truly effective therapy for CR has long been known – except, of course, to chiropractors, acupuncturists, osteopaths, and other SCAM providers who offer their services as though they are a sure solution. Sometimes, their treatments seem to work; but this could be just because the symptoms of CR can improve spontaneously, unrelated to any intervention.

The question thus arises what should these often badly suffering patients do if spontaneous remission does not occur? As an answer, let me quote from another recent systematic review of the subject: The 6 included studies that had low risk of bias, providing high-quality evidence for the surgical efficacy of Cervical Spondylotic Radiculopathy. The evidence indicates that surgical treatment is better than conservative treatment … and superior to conservative treatment in less than one year.

Menopausal symptoms are a domaine of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), not least because many women are worried about hormone treatments and therefore want ‘something natural’. TCM practitioners are only too keen to offer their services. But do their treatments really work?

This study aimed to analyze the effectiveness of acupuncture combined with Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) on mood disorder symptoms for menopausal women.

A total of 95 qualified Chinese participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups:

- 31 in the acupuncture combined with CHM group (combined group),

- 32 in the acupuncture combined with CHM placebo group (acupuncture group),

- 32 in the CHM combined with sham acupuncture group (CHM group).

The patients were treated for 8 weeks and followed up for 4 weeks. The data were collected using the Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS), self-rating depression scale (SDS), self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), and safety index.

The three groups each showed significant decreases in the GCS, SDS, and SAS after treatment (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the effect on the GCS total score and the anxiety domain lasted until the follow-up period in the combined group (p < 0.05). Within the three groups, there was no difference in GCS and SAS between the three groups after treatment (p > 0.05). However, the combined group showed significant improvement in the SDS, compared with both the acupuncture group and the CHM group at 8 weeks and 12 weeks (p < 0.05). No obvious abnormal cases were found in any of the safety indexes.

The authors concluded that the results suggest that either acupuncture, or CHM or combined therapy offer safe improvement of mood disorder symptoms for menopausal women. However, the combination therapy was associated with more stable effects in the follow-up period and a superior effect on improving depression symptoms.

Previous reviews have drawn conclusions that are far less positive, e.g.:

- the observed clinical benefit associated with acupuncture may be due, in part, or in whole to nonspecific effects.

- the evidence gathered was not sufficient to affirm the effectiveness of traditional acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture.

- For natural menopause, one large study has shown acupuncture to be superior to self-care alone in reducing the number of hot flushes and improving the quality of life; five small studies have been unable to demonstrate that the effect of acupuncture is limited to any particular points, as traditional theory would suggest; and one study showed acupuncture was superior to blunt needle for flash frequency but not intensity.

- Sham-controlled RCTs fail to show specific effects of acupuncture for control of menopausal hot flushes.

It seems therefore wise to take the conclusions of the new study with a pinch of salt. The intergroup difference observed in this trial may well be due to residual biases, multiple testing, or coincidence. And the reported intragroup differences are in complete accord with the fact that the employed therapies are mere placebos.

This, of course, begs the question of whether SCAM has anything else to offer for women suffering from menopausal symptoms. To answer it, I can refer you to one of our systematic reviews:

Some evidence exists in favour of phytosterols and phytostanols for diminishing LDL and total cholesterol in postmenopausal women. Similarly, regular fiber intake is effective in reducing serum total cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women. Clinical evidence also exists on the effectiveness of vitamin K, a combination of calcium and vitamin D or a combination of walking with other weight-bearing exercise in reducing bone mineral density loss and the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal women. Black cohosh appears to be effective therapy for relieving menopausal symptoms, primarily hot flashes, in early menopause. Phytoestrogen extracts, including isoflavones and lignans, appear to have only minimal effect on hot flashes but have other positive health effects, e.g. on plasma lipid levels and bone loss. For other commonly used CAMs, e.g. probiotics, prebiotics, acupuncture, homeopathy and DHEA-S, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are scarce and the evidence is unconvincing. More and better RCTs testing the effectiveness of these treatments are needed.

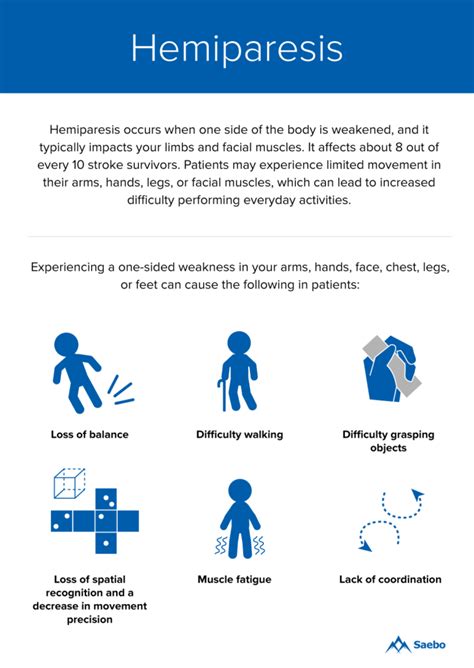

Hemiparesis is a severe impairment following a stroke that affects the majority of stroke patients. Rehabilitation is usually at least partly successful. But might results be improved with homeopathy?

This trial tested the efficacy of individualized homeopathic medicines (IHMs) in comparison with identical-looking placebos in the treatment of post-stroke hemiparesis (PSH) in the mutual context of standard physiotherapy (SP).

A 3-months, open-label, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (n = 60) was conducted at the Organon of Medicine outpatient departments of the ‘National Institute of Homoeopathy’, West Bengal, India. Patients were randomized to receive IHMs plus SP (n = 30) or identical-looking placebos plus SP (n = 30). The primary outcome measure was Medical Research Council (MRC) muscle strength grading scale; secondary outcomes were Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) version 2.0, Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS), and stroke recovery 0-100 visual analog scale (VAS) scores; all measured at baseline and 3 months after the intervention. Group differences and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated on the intention-to-treat sample.

Although overall improvements were higher in the IHMs group than in the placebo group with small to medium effect sizes, the group differences were statistically non-significant (all P>0.05, unpaired t-tests). Improvement in SIS physical problems was significantly higher with IHM than with placebo (mean difference 2.0, 95% confidence interval 0.3 to 3.8, P = 0.025, unpaired t-test). Causticum, Lachesis mutus, and Nux vomica were the most frequently prescribed medicines. No harms, unintended effects, homeopathic aggravations, or any serious adverse events were reported from either group.

The authors concluded that there was a small, but non-significant direction of effect favoring homeopathy against placebos in treatment of post-stroke hemiparesis.

Considering the fact that homeopathy has become the holy cow of India which led to the phenomenon that almost no negative homeopathy trials are being reported by Indian researchers, this article is a happy surprise. Its authors clearly report that IHM had no effect on the primary outcome measure.

Bravo!

But who had the bizarre idea that it might?

I have heard many outlandish claims by homeopaths but the one about PSH was a new one to me.

Equally puzzling is, in my view, the design of this study: it was an “open-label, randomized, placebo-controlled trial”. The reason for having a placebo group is to blind the patients, i.e. not let them know whether they receive the verum or the placebo. In an open-label trial, however, the patient is given exactly that information. I totally fail to understand the logic of this. Can someone enlighten me, please?

I had come across them so often that I had almost stopped noticing them: the ‘little extras‘ that make ineffective so-called alternative medicines (SCAMs) seem effective. Then, recently, during an interview about detox diets, the interviewer responded to my explanation of the ineffectiveness of these treatments by saying: “but these diets include stopping the consumption of alcohol, cigarettes, and other harmful stuff; therefore they must be good.” This seemingly convincing argument reminded me of a phenomenon – I call it here the ‘little extra‘ – that applies to so many (if not most) SCAMs.

Let me schematically summarise it as follows:

- A practitioner applies an ineffective SCAM to a patient.

- Because it is ineffective, it has little effect other than a small placebo response.

- The ineffective SCAM comes with a ‘little extra‘ which is unrelated to the SCAM.

- The ‘little extra‘ is effective.

- The end result is that the ineffective SCAM appears to be effective.

The above example makes it quite clear: the detox diet is utter nonsense but, as it goes hand in hand with effective lifestyle changes, it appears to be effective. A classic case. But SCAM offers no end of similar examples:

- Acupuncture is useless but it involves touch, time, attention, and empathy all of which are effective in making a patient feel better.

- Chiropractic is useless but it involves touch, time, attention, and empathy all of which are effective in making a patient feel better.

- Homeopathy is useless but it involves a long, empathic consultation and attention which are effective in making a patient feel better.

- Osteopathy is useless but it involves touch, time, attention, and empathy all of which are effective in making a patient feel better.

- Reflexology is useless but it involves touch, time, attention, and empathy all of which are effective in making a patient feel better.

Do I need to continue?

Probably not!

The ‘little extras‘ are often forgotten or subsumed under the heading ‘placebo’. Yet, they are not part of the placebo effect. Strictly speaking, they are concomitant treatments comparable to a pain patient using SCAM and also taking a few paracetamols. In the end, she forgets about the painkillers and thinks that her SCAM worked wonders.

Even ardent SCAM proponents have long realized this phenomenon. Here, for example, is a paper entitled ‘Acupuncture as a complex intervention: a holistic model’ by ex-colleagues of mine at Exeter looking at it but coming up with a very different perspective:

Objectives: Our understanding of acupuncture and Chinese medicine is limited by a lack of inquiry into the dynamics of the process. We used a longitudinal research design to investigate how the experience, and the effects, of a course of acupuncture evolved over time.

Design and outcome measures: This was a longitudinal qualitative study, using a constant comparative method, informed by grounded theory. Each person was interviewed three times over 6 months. Semistructured interviews explored people’s experiences of illness and treatment. Across-case and within-case analysis resulted in themes and individual vignettes.

Subjects and settings: Eight (8) professional acupuncturists in seven different settings informed their patients about the study. We interviewed a consecutive sample of 23 people with chronic illness, who were having acupuncture for the first time.

Results: People described their experience of acupuncture in terms of the acupuncturist’s diagnostic and needling skills; the therapeutic relationship; and a new understanding of the body and self as a whole being. All three of these components were imbued with holistic ideology. Treatment effects were perceived as changes in symptoms, changes in energy, and changes in personal and social identity. The vignettes showed the complexity and the individuality of the experience of acupuncture treatment. The process and outcome components were distinct but not divisible, because they were linked by complex connections. The paper depicts these results as a diagrammatic model that illustrates the components and their interconnections and the cyclical reinforcement, both positive and negative, that can occur over time.

Conclusions: The holistic model of acupuncture treatment, in which “the whole being greater than the sum of the parts,” has implications for service provision and for research trial design. Research trials that evaluate the needling technique, isolated from other aspects of process, will interfere with treatment outcomes. The model requires testing in different service and research settings.

I think the perspective of viewing SCAMs as complex interventions is needlessly confusing and deeply unhelpful. The truth is that there is no treatment that is not complex. Take a surgical treatment, for instance, it involves dozens of ‘little extras‘ that are known to be effective. Should we, therefore, try to use this fact for justifying useless surgical interventions? Or take a simple prescription of medication from a doctor. It involves time, empathy, attention, explanations, etc. all of which will affect the patient’s symptoms. Should we thus use this to justify a useless drug? Certainly not!

And for the same reason, it is nonsense to use the ‘little extras‘ that come with all the numerous ineffective SCAMs as a smokescreen that makes them look effective.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common condition that often frustrates all attempts of treatment. This is an ideal situation for homeopaths who claim to have the solution. Yet the evidence fails to support their optimism. The two systematic reviews on the subject are not encouraging:

- There was insufficient evidence to make recommendations on maternal allergen avoidance for disease prevention, oral antihistamines, Chinese herbs, dietary restriction in established atopic eczema, homeopathy, house dust mite reduction, massage therapy, hypnotherapy, evening primrose oil, emollients, topical coal tar and topical doxepin.

- The evidence from controlled clinical trials therefore fails to show that homeopathy is an efficacious treatment for eczema.

But now, a new study has emerged and it seems to contradict the previous conclusions. This study compared the efficacy of individualized homeopathic medicines (IHMs) against placebos in the treatment of AD.

In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 6 months duration (n = 60), adult patients were randomized to receive either IHMs (n = 30) or identical-looking placebos (n = 30). All participants received concomitant conventional care, which included the application of olive oil and maintaining local hygiene. The primary outcome measure was disease severity using the Patient-Oriented Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD) scale; secondary outcomes were the Atopic Dermatitis Burden Scale for Adults (ADBSA) and Dermatological Life Quality Index (DLQI) – all were measured at baseline and every month, up to 6 months. Group differences were calculated on the intention-to-treat sample.

After 6 months of intervention, inter-group differences became statistically significant on PO-SCORAD, the primary outcome (−18.1; 95% confidence interval, −24.0 to −12.2), favoring IHMs against placebos (F 1, 52 = 14.735; p <0.001; two-way repeated measures analysis of variance). Inter-group differences for the secondary outcomes favored homeopathy, but were overall statistically non-significant (ADBSA: F 1, 52 = 0.019; p = 0.891; DLQI: F 1, 52 = 0.692; p = 0.409).

The authors concluded that IHMs performed significantly better than placebos in reducing the severity of AD in adults, though the medicines had no overall significant impact on AD burden or DLQI.

I was unable to access the full paper, or more precisely unwilling to pay for it (in case someone has access, please post the link in the comments section below). From what can be gleaned from the abstract, this study is rigorous and clearly reported.

So, why is the outcome positive?

Pehaps one clue lies in the origin of the study. Here are the affiliations of the authors:

- 1Department of Materia Medica, Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Howrah, West Bengal, India.

- 2Department of Pathology and Microbiology, D. N. De Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

- 3Department of Pathology and Microbiology, Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal, Howrah, West Bengal, India.

- 4Department of Repertory, JIMS Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Shamshabad, Telangana, India.

- 5Department of Repertory, Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal, Howrah, West Bengal, India.

- 6Department of Health and Family Welfare, Homoeopathic Medical Officer, Rajganj State Homoeopathic Dispensary, Rajganj Government Medical College and Hospital, Uttar Dinajpur, West Bengal, India.

- 7Department of Pathology and Microbiology, National Tuberculosis Elimination Program Wing, Imambara Sadar Hospital, Hooghly, Govt. of West Bengal, India.

- 8Department of Organon of Medicine and Homoeopathic Philosophy, D. N. De Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

- 9Department of Repertory, The Calcutta Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

- 10Department of Health and Family Welfare, East Bishnupur State Homoeopathic Dispensary, Chandi Daulatabad Block Primary Health Centre, Govt. of West Bengal, India.

- 11Department of Repertory, D. N. De Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

I have previously noted that Indian studies of homeopathy (almost) never report a negative result. Why? Are the Indian homeopaths better than those elsewhere, or are they just less honest?