survey

A substantial proportion of consumers now use healthcare options known as so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). But why? This study aimed to understand the processes and decisional pathways through which chronic illness patients choose treatments outside of regular allopathic medicine.

It employed Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory methods to collect and analyze data. Using theoretical sampling, 21 individuals suffering from chronic illness and who had used SCAM treatments participated in face-to-face in-depth interviews conducted in Miami/USA.

Seven overarching themes emerged from the data to describe how and why people with chronic illness choose SCAM treatments:

- influences,

- desperation,

- being averse to allopathic medicine and allopathic medical practice,

- curiosity and chance,

- ease of access,

- institutional help,

- trial and error.

The author concluded that in selecting treatment options that include SCAM, individuals draw on their social, economic, and biographical situations. Though exploratory, this study sheds light on some of the less examined reasons for SCAM use.

There already is a plethora of research on the reasons why people elect to try SCAM. Our own systematic review of 2011 was, in my view, more informative. Here is the abstract:

The aim of this review is to summarize the published evidence regarding the expectations of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) users. We conducted electronic searches in MEDLINE and a hand search of our own files. Seventy-three articles met our inclusion criteria. A wide range of expectations emerged. In order of prevalence, they included:

- hope to influence the natural history of the disease;

- disease prevention and health/general well-being promotion;

- fewer side effects;

- being in control over one’s health;

- symptom relief;

- boosting the immune system;

- emotional support;

- holistic care;

- improving quality of life;

- relief of side effects of conventional medicine;

- good therapeutic relationship;

- obtaining information;

- coping better with illness;

- supporting the natural healing process;

- availability of treatment.

It is concluded that the expectations of SCAM users are currently not rigorously investigated. Future studies should have a clear focus on specific aspects of this broad question.

As our conclusion stated, the issue is too broad to be easily researchable. The question might need to be narrowed down. And even then, I ask myself, what might such investigations, even if done well, amount to? In what way would the results of such studies benefit anyone? How would they improve the healthcare of the future?

Perhaps someone can help me by suggesting some answers to these questions?

The use of homeopathy in oncological supportive care seems to be progressing. The first French prevalence study, performed in 2005 in Strasbourg, showed that only 17% of the subjects were using it. This descriptive study, using a questionnaire identical to that used in 2005, investigated whether the situation has changed since then.

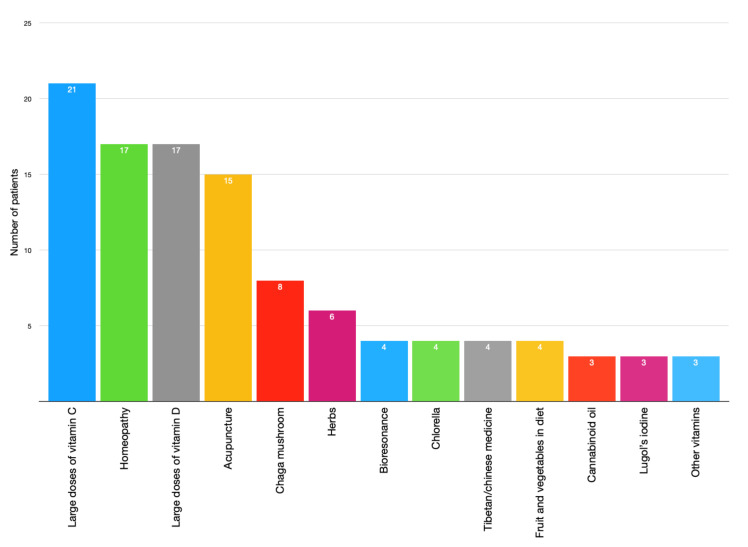

A total of 633 patients undergoing treatment in three anti-cancer centers in Strasbourg were included. The results of the “homeopathy” sub-group were extracted and studied.

Of the 535 patients included, 164 (30.7%) used homeopathy. The main purpose of its use was to reduce the side effects of cancer treatments (75%). Among the users,

- 82.6% were “somewhat” or “very” satisfied,

- 15.5% were “quite” satisfied,

- 1.9% were “not at all” satisfied.

The homeopathic treatment was prescribed by a doctor in 75.6% of the cases; the general practitioner was kept informed in 87% of the cases and the oncologist in 82%. Fatigue, pain, nausea, anxiety, sadness, and diarrhea were improved in 80% of the cases. Hair-loss, weight disorders, and loss of libido were the least improved symptoms. The use of homeopathy was significantly associated with the female sex.

The authors concluded that with a prevalence of 30.7%, homeopathy is the most used complementary medicine in integrative oncology in Strasbourg. Over 12 years, we have witnessed an increase of 83% in its use in the same city. Almost all respondents declare themselves satisfied and tell their doctors more readily than in 2005.

There is one (possibly only one) absolutely brilliant statement in this abstract:

The use of homeopathy was significantly associated with the female sex.

Why do I find this adorable?

Because to claim that any of the observed outcomes of this study are causally related to homeopathy seems like claiming that homeopathy turns male patients into women.

PS

In case you do not understand my clumsy attempt at humor and satire, rest assured: I do not truly believe that homeopathy turns men into women, and neither do I believe that it improves fatigue, pain, nausea, anxiety, sadness, and diarrhea. Remember: correlation is not causation.

A report just published by the UK GENERAL CHIROPRACTIC COUNCIL (the regulator of chiropractors in the UK) entitled Public perceptions research Enhancing professionalism, February 2021 makes interesting reading. It is based on a consumer survey for which the national online public survey was conducted by djs research in 2020 with a nationally representative sample of 1,002 UK adults (aged 16+). From this sample, 243 UK adults had received chiropractic treatment and were surveyed on their experiences of visiting a chiropractor.

Hidden amongst intensely boring stuff, we find a heading entitled Communicating potential risks. This caught my interest. Here is the unabbreviated section:

The findings show that patients want to understand the potential risks of treatment – alongside information on cost, this is the most important factor for patients considering chiropractic care. In fact, having any risks communicated before embarking on treatment scores 83 out of 100 on a scale of importance.

Many patients report receiving this information from their chiropractor. Seventy per cent of those who have received chiropractic treatment agree that risks were communicated before treatment commenced.

What does that suggest?

- Patients want to know about the risks of the treatments chiropractors administer.

- 30% of all patients are not being given this information.

This roughly confirms what has long been known:

MANY CHIROPRACTORS DO NOT OBTAIN INFORMED CONSENT FROM THEIR PATIENTS AND THUS VIOLATE MEDICAL ETHICS.

The questions that arise from this information are these:

- As the GCC has long known about this situation, why have they not adequately addressed it?

- Now that they are reminded of this flagrant ethical violation, what are they planning to do about it?

- What measures will they put in place to make sure that all chiropractors observe the elementary rules of medical ethics in the future?

- What reprimands do they plan for members who do not comply?

The objective of this survey was to determine the prevalence of Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment (OMT) use, barriers to its use, and factors that correlate with increased use.

The American Osteopathic Association (AOA) distributed its triannual survey on professional practices and preferences of osteopathic physicians, including questions on OMT, to a random sample of 10,000 osteopathic physicians in August 2018 through Survey Monkey (San Mateo, CA). Follow-up efforts included a paper survey mailed to nonrespondents one month after initial distribution and three subsequent email reminders. The survey was available from August 15, 2018, to November 5, 2018. The OMT questions focused on the frequency of OMT use, perceived barriers, and basic demographic information of osteopathic physician respondents. Statistical analysis (including a one-sample test of proportion, chi-square, and Spearman’s rho) was performed to identify significant factors influencing OMT use.

Of 10,000 surveyed osteopathic physicians, 1,683 (16.83%) responded. Of those respondents, 1,308 (77.74%) reported using OMT on less than 5% of their patients, while 958 (56.95%) did not use OMT on any of their patients. Impactful barriers to OMT use included lack of time, lack of reimbursement, lack of institutional/practice support, and lack of confidence/proficiency. Factors positively correlated with OMT use included female gender, being full owner of a practice, and practicing in an office-based setting.

The authors concluded that OMT use among osteopathic physicians in the US continues to decline. Barriers to its use appear to be related to the difficulty that most physicians have with successfully integrating OMT into the country’s insurance-based system of healthcare delivery. Follow-up investigations on this subject in subsequent years will be imperative in the ongoing effort to monitor and preserve the distinctiveness of the osteopathic profession.

What can one conclude from a three-year-old survey with a 17% response rate?

The answer is almost nothing!

Yet, it seems fair to say that OMT-use by US osteopaths is not huge. It might even be fair to speculate that, in reality, it is smaller than 17%. It stands to reason that the non-responders in this survey were the ones who could not care less about OMT. I would argue that this would be a good thing!

My ‘ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME’ is filling up nicely. But I noticed that so far we have nobody from Spain. That can be rectified ever so easily. I think I found the ideal candidate to join this group of illustrious experts who never bring themselves to publish a negative conclusion: JORGE VAS.

Jorge Vas works at the ‘Pain Treatment Unit, Doña Mercedes Primary Health Care Center, Dos Hermanas’ in Spain. I have long noticed his research which is focused on ACUPUNCTURE. From memory, I had the impression that his findings are always positive.

But is this true? To find out, I did a Medline search and found 11 clinical trials of acupuncture in his name, published between 2006 and 2019. Here are the conclusions:

- After 2 weeks of treatment, ear acupuncture applied by midwives and associated with standard obstetric care significantly reduces lumbar and pelvic pain in pregnant women, improves quality of life and reduces functional disability.

- Individualised acupuncture treatment in primary care in patients with fibromyalgia proved efficacious in terms of pain relief, compared with placebo treatment. The effect persisted at 1 year, and its side effects were mild and infrequent. Therefore, the use of individualised acupuncture in patients with fibromyalgia is recommended.

- The use of acupuncture to treat impingement syndrome seems to be a safe and reliable technique to achieve clinically significant results and could be implemented in the therapy options offered by the health services.

- …all 3 modalities of acupuncture were better than conventional treatment alone…

- Moxibustion treatment applied at acupuncture point BL67 can avoid the need for caesarean section and achieve cost savings for the healthcare system in comparison with conventional treatment.

- The application of auriculopressure in patients with non-specific spinal pain in primary healthcare is effective and safe, and therefore should be considered for inclusion in the portfolio of primary healthcare services.

- The degree of pain relief experienced by patients from acupuncture justifies a more rigorous study.

- Moxibustion at acupuncture point BL67 is effective and safe to correct non-vertex presentation when used between 33 and 35 weeks of gestation. We believe that moxibustion represents a treatment option that should be considered to achieve version of the non-vertex fetus.

- Single-point acupuncture in association with physiotherapy improves shoulder function and alleviates pain, compared with physiotherapy as the sole treatment. This improvement is accompanied by a reduction in the consumption of analgesic medicaments.

- Acupuncture plus diclofenac is more effective than placebo acupuncture plus diclofenac for the symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee.

- In the treatment of the intensity of chronic neck pain, acupuncture is more effective than the placebo treatment and presents a safety profile making it suitable for routine use in clinical practice.

Eleven of 11 trials with a positive conclusion!

That surely is a rare feast.

Actually, I cheated a tiny bit. The unabridged sentence from the conclusion of paper N4 was: In the analysis adjusted for the total sample (true acupuncture relative risk 5.04, 95% confidence interval 2.24-11.32; sham acupuncture relative risk 5.02, 95% confidence interval 2.26-11.16; placebo acupuncture relative risk 2.57 95% confidence interval 1.21-5.46), as well as for the subsample of occupationally active patients, all 3 modalities of acupuncture were better than conventional treatment alone, but there was no difference among the 3 acupuncture modalities, which implies that true acupuncture is not better than sham or placebo acupuncture. Thus this (multicentre) study was negative with just a touch of positivity.

But still, look at the range of conditions that respond positively to acupuncture in Vas’ hands. Is there anyone who doubts that Jorge Vas does not deserve to join all these other geniuses in THE ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME?

- Andreas Michalsen ( various SCAMs, Germany)

- Jennifer Jacobs (homeopath, US)

- Jenise Pellow (homeopath, South Africa)

- Adrian White (acupuncturist, UK)

- Michael Frass (homeopath, Austria)

- Jens Behnke (research officer, Germany)

- John Weeks (editor of JCAM, US)

- Deepak Chopra (entrepreneur, US)

- Cheryl Hawk (US chiropractor)

- David Peters (osteopathy, homeopathy, UK)

- Nicola Robinson (TCM, UK)

- Peter Fisher (homeopathy, UK)

- Simon Mills (herbal medicine, UK)

- Gustav Dobos (various SCAMs, Germany)

- Claudia Witt (homeopathy, Germany/Switzerland)

- George Lewith (acupuncture, UK)

- John Licciardone (osteopathy, US)

I am sure that Vas has more than merited to join them.

WELCOME JORGE VAS!

There are skeptics who keep claiming that there is no research in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). And there are plenty of SCAM enthusiasts who claim that there is an abundance of good research in SCAM.

Who is right and who is wrong?

I submit that both camps are incorrect.

To demonstrate the volume of SCAM research I looked into Medline to find the number of papers published in 2020 for the SCAMs listed below:

- acupuncture 2 752

- anthroposophic medicine 29

- aromatherapy 173

- Ayurvedic medicine 183

- chiropractic 426

- dietary supplement 5 739

- essential oil 2 439

- herbal medicine 5 081

- homeopathy 154

- iridology 0

- Kampo medicine 132

- massage 824

- meditation 780

- mind-body therapies 968

- music therapy 539

- naturopathy 68

- osteopathic manipulation 71

- Pilates 97

- qigong 97

- reiki 133

- tai chi 397

- Traditional Chinese Medicine 15 277

- yoga 698

I think the list proves anyone wrong who claims there is no (or very little) research into SCAM.

As to the enthusiasts who claim that there is plenty of good evidence, I am afraid, I disagree with them too. The above-quoted numbers are perhaps impressive to some SCAM proponents, but they are not large. To make my point more clearly, let me show you the 2020 volumes for a few topics in conventional medicine:

- psychiatry 668,492

- biologicals 300,679

- chemotherapy 109,869

- radiotherapy 17,964

- rehabilitation 21,751

- rehabilitation medicine 21,751

- surgery 256,958

I think we can agree that these figures make the SCAM numbers look pitifully small.

But the more important point is, I think, not the quantity but the quality of the SCAM research. As this whole blog is about the often dismal rigor of SCAM research, I do surely not need to produce further evidence to convince you that it is poor, often even very poor.

So, both camps tend to be incorrect when they speak about SCAM research. The truth is that there is quite a lot, but sadly reliable studies are like gold dust.

But actually, when I started writing this post and doing all these Medline searches to produce the above-listed volumes of SCAM research, I was thinking of a different subject entirely. I wanted to see which areas of SCAM were research-active and which are not. This is why I chose terms for my list that do not overlap with others (yet we need to realize that the figures are not precise due to misclassification and other factors). And in this respect, the list is interesting too, I find.

It identifies the SCAMs that are remarkably research-inactive:

- anthroposophic medicine

- iridology

- naturopathy

- osteopathy

- Pilates

- qigong

Perhaps more interesting are the areas that show a relatively high research activity:

- acupuncture

- dietary supplements

- essential oils

- herbal medicine

- massage

- meditation

- mind-body therapies

- TCM

- yoga

This, in turn, suggests two things:

- It is not true that only commercial interests drive research activity.

- The Chinese (TCM and acupuncture) are pushing the ferociously hard to conquer SCAM research.

The last point is worrying, in my view, because we know from several independent studies that Chinese studies are often the flimsiest and least reliable of all the SCAM literature. As I have suggested recently, the unreliability of SCAM research might one day be its undoing: This self-destructive course of SCAM might be applauded by some skeptics. However, if you believe (as I do) that there are a few good things to be found in SCAM, this development can only be regrettable. I fear that the growing dominance of Chinese research will help to speed up this process.

The purpose of this survey (the authors call it a ‘study’) was to evaluate the patient-perceived benefit of yoga for symptoms commonly experienced by breast cancer survivors.

A total of 1,049 breast cancer survivors who had self-reported use of yoga on a follow-up survey, in an ongoing prospective Mayo Clinic Breast Disease Registry (MCBDR), received an additional mailed yoga-focused survey asking about the impact of yoga on a variety of symptoms. Differences between pre-and post- scores were assessed using Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

802/1,049 (76%) of women who were approached to participate, consented and returned the survey. 507/802 (63%) reported use of yoga during and/or after their cancer diagnosis. The vast majority of respondents (89.4%) reported some symptomatic benefit from yoga. The most common symptoms that prompted the use of yoga were breast/chest wall pain, lymphedema, and anxiety. Only 9% of patients reported that they had been referred to yoga by a medical professional. While the greatest symptom improvement was reported with breast/chest wall pain and anxiety, significant improvement was also perceived in joint pain, muscle pain, fatigue, headache, quality of life, hot flashes, nausea/vomiting, depression, insomnia, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy, (all p-values <0.004).

The authors concluded that data supporting the use of yoga for symptom management after cancer are limited and typically focus on mental health. In this study, users of yoga often reported physical benefits as well as mental health benefits. Further prospective studies investigating the efficacy of yoga in survivorship are warranted.

I have little doubt that yoga is helpful during palliative and supportive cancer care (but all the more doubts that this new paper will further the reputation of research in this area). In fact, contrary to what the conclusions state, there is quite good evidence for this assumption:

- A 2009 systematic review included 10 clinical trials. Its authors concluded that although some positive results were noted, variability across studies and methodological drawbacks limit the extent to which yoga can be deemed effective for managing cancer-related symptoms.

- A 2017 systematic review with 25 clinical trials concluded that among adults undergoing cancer treatment, evidence supports recommending yoga for improving psychological outcomes, with potential for also improving physical symptoms. Evidence is insufficient to evaluate the efficacy of yoga in pediatric oncology.

- A 2017 Cochrane review included 24 studies and found that moderate-quality evidence supports the recommendation of yoga as a supportive intervention for improving health-related quality of life and reducing fatigue and sleep disturbances when compared with no therapy, as well as for reducing depression, anxiety and fatigue, when compared with psychosocial/educational interventions. Very low-quality evidence suggests that yoga might be as effective as other exercise interventions and might be used as an alternative to other exercise programmes.[3]

So, why publish a paper like the one above?

Search me!

To be able to add one more publication to the authors’ lists?

And why would the journal editor go along with this nonsense?

Search me again!

No, hold on: Global Advances in Health and Medicine, the journal that carried the survey, is published in association with Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine & Health.

Yes, that explains a lot.

As I have pointed out several times before, surveys of this nature are like going into a Mac Donald’s and asking the customers whether they like Hamburgers. You might then also find that “the vast majority of respondents (89.4%) reported”… blah, blah, blah.

The title of the paper is ‘Real-World Experiences With Yoga on Cancer-Related Symptoms in Women With Breast Cancer‘.

PS

NOTE TO MYSELF: never touch a paper with ‘real-world experience’ in the title.

The objective of this survey was to determine

- which patients’ characteristics are associated with the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) during cancer treatment,

- their pattern of use,

- and if it has any association with its safety profile.

A total of 316 patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment in cancer centers in Poland between 2017 and 2019 were asked about their use of SCAM.

Patients’ opinion regarding the safety of unconventional methods is related to the use of SCAM. Moreover, patients’ thinking that SCAM can replace conventional therapy was correlated with his/her education. Moreover, the researchers performed analyses to determine factors associated with SCAM use including sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Crucially, they also conducted a survival analysis of patients undergoing chemotherapy with 42 months of follow-up. Using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank analysis, they found no statistical difference in overall survival between the groups that used and did not use any form of SCAM.

The authors concluded that SCAM use is common among patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment and should be considered by medical teams as some agents may interact with chemotherapy drugs and affect their efficacy or cause adverse effects.

As I have stated before, I find most surveys of SCAM use meaningless. This article is no exception – except for the survival analysis. It would have merited a separate, more detailed paper, yet the authors hardly comment on it. The analysis shows that SCAM users do not live longer than non-users. Previously, we have discussed several studies that suggested they live less long than non-users.

While this aspect of the new study is interesting, it proves very little. There are, of course, multiple factors involved in the survival of cancer patients, and even if SCAM use were a determinant, it is surely less important than many other factors. To get a better impression of the role SCAM plays, we need studies that carefully match patients according to the most obvious prognostic variables (RCTs would be problematic, difficult to do and unethical). Such studies do exist and they too fail to show that SCAM use prolongs survival, some even suggest it might shorten survival.

The state of acupuncture research has long puzzled me. The first thing that would strike who looks at it is its phenomenal increase:

- Until around the year 2000, Medline listed about 200 papers per year on the subject.

- From 2005, there was a steep, near-linear increase.

- It peaked in 2020 when we had a record-breaking 20515 acupuncture papers currently listed in Medline.

Which this amount of research, one would expect to get somewhere. In particular, one would hope to slowly know whether acupuncture works and, if so, for which conditions. But this is not the case.

On the contrary, the acupuncture literature is a complete mess in which it gets more and more difficult to differentiate the reliable from the unreliable, the useful from the redundant, and the truth from the lies. Because of this profound confusion, acupuncture fans are able to claim that their pet-therapy is demonstrably effective for a wide range of conditions, while skeptics insist it is a theatrical placebo. The consumer might listen in bewilderment.

Yesterday (18/1/2021), I had a quick (actually, it was not that quick after all) look into what Medline currently lists in terms of new acupuncture research published in 2021 and found a few other things that are remarkable:

- There were already 100 papers dated 2021 (today, there were even 118); that corresponds to about 5 new articles per day and makes acupuncture one of the most research-active areas of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

- Of these 100 papers, only 7 were clinical trials (CTs). In my view, clinical trials would be more important than any other type of research on acupuncture. To see that they amount to just 7% of the total is therefore disappointing.

- Twelve papers were systematic reviews (SRs). It is odd, I find, to see almost twice the amount of SRs than CTs.

- Eighteen papers referred to protocols of studies of SRs. In particular protocols of SRs are useless in my view. It seems to me that the explanation for this plethora of published protocols might be the fact that Chinese researchers are extremely keen to get papers into Western journals; it is an essential boost to their careers.

- Seven papers were surveys. This multitude of survey research is typical for all types of SCAM.

- Twenty-four articles were on basic research. I find basic research into an ancient therapy of questionable clinical use more than a bit strange.

- The rest of the articles were other types of publications and a few were misclassified.

- The vast majority (n = 81) of the 100 papers were authored exclusively by Chinese researchers (and a few Korean). In view of the fact that it has been shown repeatedly that practically all acupuncture studies from China report positive results and that data fabrication seems rife in China, this dominance of China could be concerning indeed.

Yes, I find all this quite concerning. I feel that we are swamped with plenty of pseudo-research on acupuncture that is of doubtful (in many cases very doubtful) reliability. Eventually, this will create an overall picture for the public that is misleading to the extreme (to check the validity of the original research is a monster task and way beyond what even an interested layperson can do).

And what might be the solution? I am not sure I have one. But for starters, I think, that journal editors should get a lot more discerning when it comes to article submissions from (Chinese) acupuncture researchers. My advice to them and everyone else:

if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is!

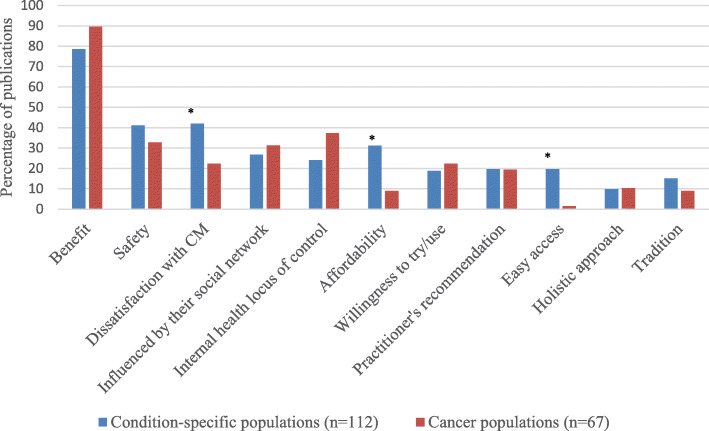

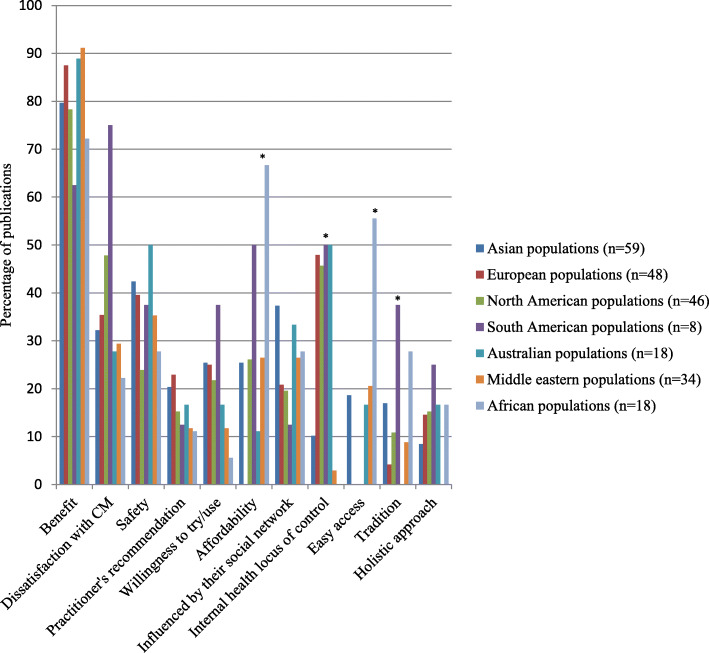

The authors of this review wanted to determine similarities and differences in the reasons for using or not using so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) amongst general and condition-specific populations, and amongst populations in each region of the globe.

Quantitative or qualitative original articles in English, published between 2003 and 2018 were reviewed. Conference proceedings, pilot studies, protocols, letters, and reviews were excluded. Papers were appraised using valid tools and a ‘risk of bias’ assessment was also performed. Thematic analysis was conducted. Reasons were coded in each paper, then codes were grouped into categories. If several categories reported similar reasons, these were combined into a theme. Themes were then analysed using χ2 tests to identify the main factors related to reasons for CAM usage.

A total of 231 publications were included. Reasons for SCAM use amongst general and condition-specific populations were similar. The top three reasons were:

- (1) having an expectation of benefits of SCAM (84% of publications),

- (2) dissatisfaction with conventional medicine (37%),

- (3) the perceived safety of SCAM (37%).

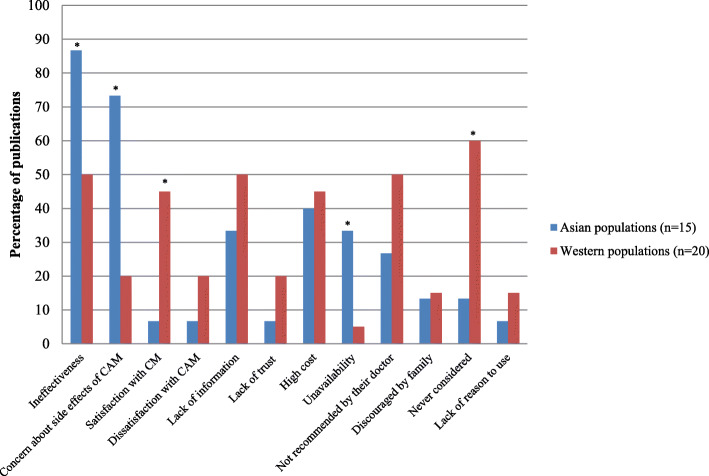

Internal health locus of control as an influencing factor was more likely to be reported in Western populations, whereas the social networks was a common factor amongst Asian populations (p < 0.05). Affordability, easy access to SCAM and tradition were significant factors amongst African populations (p < 0.05). Negative attitudes towards SCAM and satisfaction with conventional medicine were the main reasons for non-use (p < 0.05).

The authors concluded that dissatisfaction with conventional medicine and positive attitudes toward SCAM, motivate people to use SCAM. In contrast, satisfaction with conventional medicine and negative attitudes towards SCAM are the main reasons for non-use.

At this point, I thought: so what? This is all very obvious and does not necessitate an extensive review of the published literature. What it actually shows is that the realm of SCAM is obsessed with conducting largely useless surveys, a phenomenon, I once called ‘survey mania‘. But a closer look at the review does reveal some potentially interesting findings.

In less developed parts of the world, like Africa, SCAM use seems to be determined by affordability, accessibility and tradition. This makes sense and ties in with my impression that consumers in such countries would give up SCAM as soon as they can afford proper medicine.

This notion seems to be further supported by the reasons for not using SCAM. Asian consumers claim overwhelmingly that this is because they consider SCAM ineffective and unsafe.

In our review of 2011 (not cited in the new review), we looked at some of the issues from a slightly different angle and evaluated the expectations of SCAM users. Seventy-three articles met our inclusion criteria of our review. A wide range of expectations emerged. In order of prevalence, they included:

- the hope to influence the natural history of the disease;

- the desire to prevent disease and promote health/general well-being;

- the hope of fewer side effects;

- the wish to be in control over one’s health;

- the hope for symptom relief;

- the ambition to boost the immune system;

- the hope to receive emotional support;

- the wish to receive holistic care;

- the hope to improve quality of life;

- the expectation to relief of side effects of conventional medicine;

- the desire for a good therapeutic relationship;

- the hope to obtain information;

- the hope of coping better with illness;

- the expectation of supporting the natural healing process;

- the availability of SCAM.

All of these aspects, issues and notions might be interesting, even fascinating to some, but we should not forget three important caveats:

- Firstly, SCAM is such a diverse area that any of the above generalisations are highly problematic; the reasons and expectations of someone trying acupuncture may be entirely different from those of someone using homeopathy, for instance.

- Secondly (and more importantly), the ‘survey mania’ of SCAM researchers has not generated the most reliable data; in fact, most of the papers are hardly worth the paper they were printed on.

- Thirdly (and even more importantly, in my view), why should any of this matter? We have known about some of these issues for at least 3 decades. Has this line of research changed anything? Has it prevented consumers getting exploited by scrupulous SCAM entrepreneurs? Has it made consumers, politicians or anyone else more aware of the risks associated with SCAM? Has it saved many lives? I doubt it!