study design

This study assessed the effectiveness of Oscillococcinum in the protection from upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) in patients with COPD who had been vaccinated against influenza infection over the 2018-2019 winter season.

A total of 106 patients were randomized into two groups:

- group V received influenza vaccination only

- group OV received influenza vaccination plus Oscillococcinum® (one oral dose per week from inclusion in the study until the end of follow-up, with a maximum of 6 months follow-up over the winter season).

The primary endpoint was the incidence rate of URTIs (number of URTIs/1000 patient-treatment exposure days) during follow-up compared between the two groups.

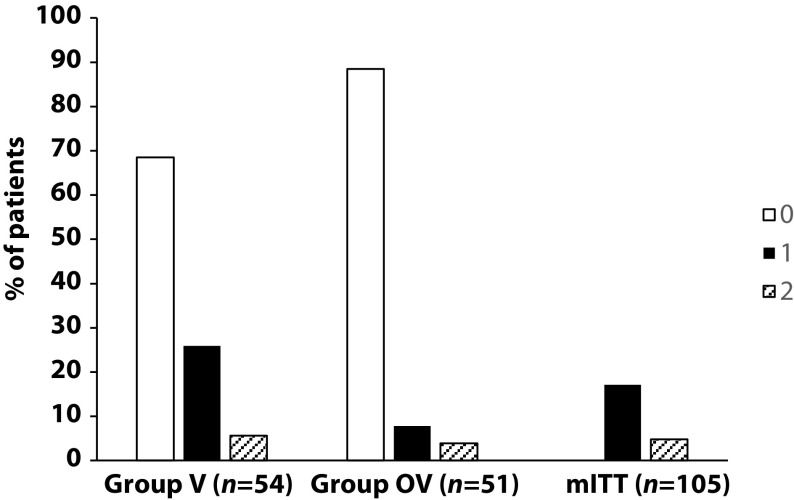

There was no significant difference in any of the demographic characteristics, baseline COPD, or clinical data between the two treatment groups (OV and V). The URTI incidence rate was significantly higher in group V than in group OV (2.9 versus 1.2 episodes/1000 treatment days, difference OV-V = -1.7; p=0.0312). There was a significant delay in occurrence of an URTI episode in the OV group versus the V group (mean ± standard error: 48.7 ± 3.0 versus 67.0 ± 2.8 days, respectively; p=0.0158). Limitations to this study include its small population size and the self-recording by patients of the number and duration of URTIs and exacerbations.

The authors concluded that the use of Oscillococcinum in patients with COPD led to a significant decrease in incidence and a delay in the appearance of URTI symptoms during the influenza-exposure period. The results of this study confirm the impact of this homeopathic medication on URTIs in patients with COPD.

Primary endpoint, comparison of the number of upper respiratory tract infections in the two treatment groups during follow-up

This prospective, randomized, single-center study was funded by Laboratoires Boiron, was conducted in the Pneumology Department of Charles Nicolle Hospital, Tunis, and was written up by a commercial firm specializing in writing for the pharmaceutical industry. The latter point may explain why it reads well and elegantly glosses over the many flaws of the trial.

If I did not know better, I might suspect that the study was designed to deceive us (Boiron would, of course, never do this!): The primary endpoint was the incidence rate of URTIs (number of URTIs/1000 patient-treatment exposure days) in the two groups during the follow-up period. This rate is calculated as the number of episodes of URTIs per 1000 days of follow-up/treatment exposure. The rates were then compared between the OV and V groups. The following symptoms were considered indicative of an URTI: fever, shivering, runny or blocked nose, sneezing, muscular aches/pain, sore throat, watery eyes, headaches, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, fatigue and loss of appetite.

This means that there was no verification whatsoever of the primary endpoint. In itself, this flaw would perhaps not be so bad. But put it together with the fact that patients were not blinded (there were no placebos!), it certainly is fatal.

In essence, the study shows that patients who perceive to receive treatment will also perceive to have fewer URTIs.

SURPRISE, SURPRISE!

This systematic review summarized the evidence of the effects of dance/movement therapy (DMT) on mental health outcomes and quality of life in breast cancer patients.

Ninety-four articles were found. Only empirical interventional studies (N = 6) were selected for the review:

- randomised controlled trials (RCT) (n = 5)

- non-RCT (n = 1).

Data from 6 studies including 385 participants who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, were of an average age of 55.7 years, and had participated in DMT programmes for 3–24 weeks were analysed.

In each study, the main outcomes that were measured were

- quality of life,

- physical activity,

- stress,

- emotional and social well-being.

Different questionnaires were used for the evaluation of outcomes. The mental health of the participants who received DMT intervention improved: they reported a better quality of life and decreased stress, symptoms, and fatigue.

The authors concluded that DMT could be successfully used as a complimentary therapy in addition to standard cancer treatment for improving the quality of life and mental health of women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer. More research is needed to evaluate the complexity of the impact of complimentary therapies. It is possible that DMT could be more effective if used with other therapies.

The American Dance Therapy Association defines DMT as a multidimensional approach that integrates body awareness, creative expression, and the psychotherapeutic use of movement to promote the emotional, social, cognitive, and physical integration of the individual to improve health and well-being. The European Association of Dance Movement Therapy adds “spiritual integration” to this list. The types of dance used in the primary studies varied (from traditional Greek to belly dancing), and for none was there more than one study. No study of eurythmy (the anthroposophical dance therapy) was included.

I do not find it hard to imagine that DMT helps some cancer patients. Yet, I find the rigor of both the review and the primary studies somewhat wanting. The review authors, for instance, claimed that they followed the PRISMA guidelines; this is, however, not the case. The primary studies tested DMT mostly against no therapy at all which means that no attempts were made to control for non-specific effects.

I think the most obvious conclusion is that, during their supportive care, cancer patients can benefit from

- attention,

- empathy

- movement,

- self-expression,

- social interaction,

- etc.

This, however, is not the same as claiming that DMT is the best option for them.

The ‘Control Group Cooperative Ltd‘ is a UK Company (Registration Number: 13477806) is registered at 117 Dartford Road, Dartford, Kent DA1 3EN, UK. On its website, it provides the following statement:

The Vaccine Control Group is a Worldwide independent long-term study that is seeking to provide a baseline of data from unvaccinated individuals for comparative analysis with the vaccinated population, to evaluate the success of the Covid-19 mass vaccination programme and assist future research projects. This study is not, and will never be, associated with any pharmaceutical enterprise as its impartiality is of paramount importance.

The VaxControlGroup is a community cooperative, for the people. All monies raised will be re-invested into the project and its community.

Volunteers for this study are welcome from around the world, providing they have not yet received any of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and are not planning to do so.

So, the Vaccine Control Group (VCC) aims at recruiting people who refuse COVID vaccinations. The VCC issues downloadable and printable COVID-19 Vaccine self exemption forms that you can complete (either online or by hand) supplied by: Professionals for Medical Informed Consent and Non-Discrimination (PROMIC). The form contains the following text:

COVID-19 vaccines, that have been administered to the public under emergency use authorisation, have been

associated with moderate to severe adverse events and deaths in a small proportion of recipients. There are currently insufficient available long-term safety data from Phase 3 trials and post-marketing surveillance to be able to predict which population sub-groups are likely to be most vulnerable to these reactions. However, clinical assessments have identified a range of conditions or medical histories that are associated with increased risk of serious adverse events (see Panel B). Individuals with such medical concerns, along with those who have already had COVID-19 and acquired natural immunity, have justifiable grounds to not consent to COVID-19 vaccination. Such individuals may choose to use alternate approaches to reduce their risk of developing serious COVID-19 disease and associated viral transmission. UK and international law enshrines an individual’s right to refuse any medical treatment or intervention without being subjected to penalty, restriction or limitation of protected rights or freedoms, as this would otherwise constitute coercion.

I do wonder, after reading this, what scientific value this ‘study’ might have (nowhere could I find relevant methodological details about the ‘study’). In search of an answer, I found ‘Doctors & Health Professionals supportive of this project’. The only one supportive of the VCC seems to be Prof Harald Walach who offers his support with these words:

A vaccine control group, especially for Covid-19 vaccines, is extremely useful, even necessary, for the following reasons:

- We are dealing with a vaccination technology that has never been used in humans before.

- All studies that have planned a control group long term, i.e. longer than only 6 weeks, have meanwhile been compromised, i.e. there are no real control groups around, because those originally allocated to the control group have mostly been vaccinated now. So there are no real control groups available.

- Covid-19 vaccinations are one of the biggest experiments on mankind ever conducted – without a control group. Hence those, who are either not willing to be vaccinated or have not yet been vaccinated are our only chance to understand whether the vaccines are safe or whether symptoms reported after vaccination are actually due to the vaccination or are only an incidental occurrence or random fluctuation.

Comparing unvaccinated people and those with a vaccination history regarding Covid-19 vaccines long term is important to determine long-term safety, because in many instances in the past some problems only were seen after quite some time. This can happen, if auto-immune processes are triggered, which often occur only in very few people. Hence, it is also important to have a long-term observation period and a large number of people participating.

Prof. Dr. Dr. phil. Harald Walach

This does not alleviate my doubts about the scientific value at all. Prof Walach, promoter of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and pseudoscientist of the year 2012, has in the past drawn our attention to his odd activities around COVID and vaccinations. Here are three recent posts on the subject:

- Prof Harald Walach is really unlucky

- Is Prof Harald Walach incompetent or dishonest?

- COVID-19 vaccinations: Prof Walach wants to “dampen the enthusiasm by sober facts”

In view of all this, I do wonder what the VCC is truly about.

It couldn’t be a front for issuing dodgy exemption certificates, could it?

This review summarized the available evidence on so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) used with radiotherapy. Systematic literature searches identified studies on the use of SCAM during radiotherapy. Inclusion required the following criteria: the study was interventional, SCAM was for human patients with cancer, and SCAM was administered concurrently with radiotherapy. Data points of interest were collected from included studies. A subset was identified as high-quality using the Jadad scale. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the association between study results, outcome measured, and type of SCAM.

Overall, 163 articles met inclusion. Of these, 68 (41.7%) were considered high-quality trials. Articles published per year increased over time. Frequently identified therapies were biologically based therapies (47.9%), mind-body therapies (23.3%), and alternative medical systems (13.5%). Within the subset of high-quality trials, 60.0% of studies reported a favorable change with SCAM while 40.0% reported no change. No studies reported an unfavorable change. Commonly assessed outcome types were patient-reported (41.1%) and provider-reported (21.5%). The rate of favorable change did not differ based on the type of SCAM or outcome measured.

The authors concluded that concurrent SCAM may reduce radiotherapy-induced toxicities and improve quality of life, suggesting that physicians should discuss SCAM with patients receiving radiotherapy. This review provides a broad overview of investigations on SCAM use during radiotherapy and can inform how radiation oncologists advise their patients about SCAM.

In my recent book, I have reviewed the somewhat broader issue of SCAM for palliative and supportive care. My conclusions are broadly in agreement with the above review:

… some forms of SCAM—by no means all— benefit cancer patients in multiple ways… four important points:

• The volume of the evidence for SCAM in palliative and supportive cancer care is currently by no means large.

• The primary studies are often methodologically weak and their findings are contradictory.

• Several forms of SCAM have the potential to be useful in palliative and supportive cancer care.

• Therefore, generalisations are problematic, and it is wise to go by the current best evidence …

One particular finding of the new review struck me as intriguing: The rate of favorable change did not differ based on the type of SCAM. Combined with the fact that most studies are less than rigorous and fail to control for non-specific effects, this indicates to me that, in cancer palliation (and perhaps in other areas as well), SCAM works mostly via non-specific effects. In other words, patients feel better not because the treatment per se was effective but because they needed the extra care, attention, and empathy.

If this is true, it carries an important reminder for oncology: cancer patients are very vulnerable and need all the empathy and compassion they can get. Seen from this perspective, the popularity of SCAM would be a criticism of conventional medicine for not providing enough of it.

Muscular dystrophies are a rare, severe, and genetically inherited disorders characterized by progressive loss of muscle fibers, leading to muscle weakness. The current treatment includes the use of steroids to slow muscle deterioration by dampening the inflammatory response. Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) has been offered as adjunctive therapy in Taiwan’s medical healthcare plan, making it possible to track CHM usage in patients with muscular dystrophies. This investigation explored the long-term effects of CHM use on the overall mortality of patients with muscular dystrophies.

A total of 581 patients with muscular dystrophies were identified from the database of Registry for Catastrophic Illness Patients in Taiwan. Among them, 80 and 201 patients were CHM users and non-CHM users, respectively. Compared to non-CHM users, there were more female patients, more comorbidities, including chronic pulmonary disease and peptic ulcer disease in the CHM user group. After adjusting for age, sex, use of CHM, and comorbidities, patients with prednisolone usage exhibited a lower risk of overall mortality than those who did not use prednisolone. CHM users showed a lower risk of overall mortality after adjusting for age, sex, prednisolone use, and comorbidities. The cumulative incidence of the overall survival was significantly higher in CHM users. One main CHM cluster was commonly used to treat patients with muscular dystrophies; it included Yin-Qiao-San, Ban-Xia-Bai-Zhu-Tian-Ma-Tang, Zhi-Ke (Citrus aurantium L.), Yu-Xing-Cao (Houttuynia cordata Thunb.), Che-Qian-Zi (Plantago asiatica L.), and Da-Huang (Rheum palmatum L.).

The authors concluded that the data suggest that adjunctive therapy with CHM may help to reduce the overall mortality among patients with muscular dystrophies. The identification of the CHM cluster allows us to narrow down the key active compounds and may enable future therapeutic developments and clinical trial designs to improve overall survival in these patients.

I disagree!

What the authors have shown is a CORRELATION, and from that, they draw conclusions implying CAUSATION. This is such a fundamental error that one has to wonder why a respected journal let it go past.

A likely causative explanation of the findings is that the CHM group of patients differed in respect to features that the statistical evaluations could not control for. Statisticians can never control for factors that have not been measured and are thus unknown. A possibility in the present case is that these patients had adopted a different lifestyle together with employing CHM which, in turn, resulted in a longer survival.

Therapeutic touch (TT) is a form of paranormal or energy healing developed by Dora Kunz (1904-1999), a psychic and alternative practitioner, in collaboration with Dolores Krieger, a professor of nursing. TT is popular and practised predominantly by US nurses; it is currently being taught in more than 80 colleges and universities in the U.S., and in more than seventy countries. According to one TT-organisation, TT is a holistic, evidence-based therapy that incorporates the intentional and compassionate use of universal energy to promote balance and well-being. It is a consciously directed process of energy exchange during which the practitioner uses the hands as a focus to facilitate the process.

The question is: does TT work beyond a placebo effect?

This review synthesized recent (January 2009–June 2020) investigations on the effectiveness and safety of therapeutic touch (TT) as a therapy in clinical health applications. A rapid evidence assessment (REA) approach was used to review recent TT research adopting PRISMA 2009 guidelines. CINAHL, PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane databases, Web of Science, PsychINFO, and Google Scholar were screened between January 2009-March 2020 for studies exploring TT therapies as an intervention. The main outcome measures were for pain, anxiety, sleep, nausea, and functional improvement.

Twenty-one studies covering a range of clinical issues were identified, including 15 randomized controlled trials, four quasi-experimental studies, one chart review study, and one mixed-methods study including 1,302 patients. Eighteen of the studies reported positive outcomes. Only four exhibited a low risk of bias. All others had serious methodological flaws, bias issues, were statistically underpowered, and scored as low-quality studies. Over 70% of the included studies scored the lowest score possible on the GSRS weight of evidence scale. No high-quality evidence was found for any of the benefits claimed.

The authors drew the following conclusions:

After 45 years of study, scientific evidence of the value of TT as a complementary intervention in the management of any condition still remains immature and inconclusive:

- Given the mixed result, lack of replication, overall research quality and significant issues of bias identified, there currently exists no good quality evidence that supports the implementation of TT as an evidence‐based clinical intervention in any context.

- Research over the past decade exhibits the same issues as earlier work, with highly diverse poor quality unreplicated studies mainly published in alternative health media.

- As the nature of human biofield energy remains undemonstrated, and that no quality scientific work has established any clinically significant effect, more plausible explanations of the reported benefits are from wishful thinking and use of an elaborate theatrical placebo.

TT turns out to be a prime example of a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that enthusiastic amateurs, who wanted to prove TT’s effectiveness, have submitted to multiple trials. Thus the literature is littered with positive but unreliable studies. This phenomenon can create the impression – particularly to TT fans – that the treatment works.

This course of events shows in an exemplary fashion that research is not always something that creates progress. In fact, poor research often has the opposite effect. Eventually, a proper scientific analysis is required to put the record straight (the findings of which enthusiasts are unlikely to accept).

In view of all this, and considering the utter implausibility of TT, it seems an unethical waste of resources to continue researching the subject. Similarly, continuing to use TT in clinical settings is unethical and potentially dangerous.

Kneipp therapy goes back to Sebastian Kneipp (1821-1897), a catholic priest who was convinced to have cured himself of tuberculosis by using various hydrotherapies. Kneipp is often considered by many to be ‘the father of naturopathy’. Kneipp therapy consists of hydrotherapy, exercise therapy, nutritional therapy, phototherapy, and ‘order’ therapy (or balance). Kneipp therapy remains popular in Germany where whole spa towns live off this concept.

The obvious question is: does Kneipp therapy work? A team of German investigators has tried to answer it. For this purpose, they conducted a systematic review to evaluate the available evidence on the effect of Kneipp therapy.

A total of 25 sources, including 14 controlled studies (13 of which were randomized), were included. The authors considered almost any type of study, regardless of whether it was a published or unpublished, a controlled or uncontrolled trial. According to EPHPP-QAT, 3 studies were rated as “strong,” 13 as “moderate” and 9 as “weak.” Nine (64%) of the controlled studies reported significant improvements after Kneipp therapy in a between-group comparison in the following conditions:

- chronic venous insufficiency,

- hypertension,

- mild heart failure,

- menopausal complaints,

- sleep disorders in different patient collectives,

- as well as improved immune parameters in healthy subjects.

No significant effects were found in:

- depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients with climacteric complaints,

- quality of life in post-polio syndrome,

- disease-related polyneuropathic complaints,

- the incidence of cold episodes in children.

Eleven uncontrolled studies reported improvements in allergic symptoms, dyspepsia, quality of life, heart rate variability, infections, hypertension, well-being, pain, and polyneuropathic complaints.

The authors concluded that Kneipp therapy seems to be beneficial for numerous symptoms in different patient groups. Future studies should pay even more attention to methodologically careful study planning (control groups, randomisation, adequate case numbers, blinding) to counteract bias.

On the one hand, I applaud the authors. Considering the popularity of Kneipp therapy in Germany, such a review was long overdue. On the other hand, I am somewhat concerned about their conclusions. In my view, they are far too positive:

- almost all studies had significant flaws which means their findings are less than reliable;

- for most indications, there are only one or two studies, and it seems unwarranted to claim that Kneipp therapy is beneficial for numerous symptoms on the basis of such scarce evidence.

My conclusion would therefore be quite different:

Despite its long history and considerable popularity, Kneipp therapy is not supported by enough sound evidence for issuing positive recommendations for its use in any health condition.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) causes a range of different symptoms. Patients with MS have looked for alternative therapies to control their MS progress and treat their symptoms. Non-invasive therapeutic approaches such as massage can have benefits to mitigate some of these symptoms. However, there is no rigorous review of massage effectiveness for patients suffering from MS.

The present systematic review was aimed at examining the effectiveness of different massage approaches on common MS symptoms, including fatigue, pain, anxiety, depression, and spasticity.

A total of 12 studies met the inclusion criteria. The authors rated 5 studies as being of fair and 7 studies of good methodological quality. Fatigue was improved by different massage styles, such as reflexology, nonspecific therapeutic massage, and Swedish massage. Pain, anxiety, and depression were effectively improved by reflexology techniques. Spasticity was reduced by Swedish massage and reflexology techniques.

The authors concluded that different massage approaches effectively improved MS symptoms such as fatigue, pain, anxiety, depression, and spasticity.

Clinical trials of massage therapy face formidable obstacles including:

- difficulties in obtaining funding,

- difficulties in finding expert researchers who are interested in the subject,

- difficulties to control for placebo effects,

- difficulties in blinding patients,

- impossibility of blinding therapists,

- confusion about the plethora of different massage techniques.

Thus, the evidence is often less convincing than one would hope. This, however, does not mean that massage therapy does not have considerable potential for a range of indications. One could easily argue that this situation is similar to spinal manipulation. Yet, there are at least three important differences:

- massage therapy is not as heavily burdened with frequent adverse effects and potentially life-threatening complications,

- massage therapy has a rational basis,

- the existing evidence is more uniformly encouraging.

Consequently, massage therapy (particularly, classic or Swedish massage) is more readily being accepted even in the absence of solid evidence. In fact, in some countries, e.g. Germany and Austria, massage therapy is considered to be a conventional treatment.

This multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled trial was aimed at assessing the long-term efficacy of acupuncture for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). Men with moderate to severe CP/CPPS were recruited, regardless of prior exposure to acupuncture. They received sessions of acupuncture or sham acupuncture over 8 weeks, with a 24-week follow-up after treatment. Real acupuncture treatment was used to create the typical de qi sensation, whereas the sham acupuncture treatment (the authors state they used the Streitberger needle, but the drawing looks more as though they used our device) does not generate this feeling.

The primary outcome was the proportion of responders, defined as participants who achieved a clinically important reduction of at least 6 points from baseline on the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index at weeks 8 and 32. Ascertainment of sustained efficacy required the between-group difference to be statistically significant at both time points.

A total of 440 men (220 in each group) were recruited. At week 8, the proportions of responders were:

- 60.6% (95% CI, 53.7% to 67.1%) in the acupuncture group

- 36.8% (CI, 30.4% to 43.7%) in the sham acupuncture group (adjusted difference, 21.6 percentage points [CI, 12.8 to 30.4 percentage points]; adjusted odds ratio, 2.6 [CI, 1.8 to 4.0]; P < 0.001).

At week 32, the proportions were:

- 61.5% (CI, 54.5% to 68.1%) in the acupuncture group

- 38.3% (CI, 31.7% to 45.4%) in the sham acupuncture group (adjusted difference, 21.1 percentage points [CI, 12.2 to 30.1 percentage points]; adjusted odds ratio, 2.6 [CI, 1.7 to 3.9]; P < 0.001).

Twenty (9.1%) and 14 (6.4%) adverse events were reported in the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups, respectively. No serious adverse events were reported. No significant difference was found in changes in the International Index of Erectile Function 5 score at all assessment time points or in peak and average urinary flow rates at week 8.

The authors concluded that, compared with sham therapy, 20 sessions of acupuncture over 8 weeks resulted in greater improvement in symptoms of moderate to severe CP/CPPS, with durable effects 24 weeks after treatment.

The study was sponsored by the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The trialists originate from the following institutions:

- 1Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China (Y.S., B.L., Z.Q., J.Z., J.W., X.L., W.W., R.P., H.C., X.W., Z.L.).

- 2Key Laboratory of Chinese Internal Medicine of Ministry of Education, Dongzhimen Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China (Y.L.).

- 3ThedaCare Regional Medical Center – Appleton, Appleton, Wisconsin (K.Z.).

- 4Hengyang Hospital Affiliated to Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Hengyang, China (Z.Y.).

- 5The First Hospital of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, China (W.Z.).

- 6Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China (W.F.).

- 7The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, Hefei, China (J.Y.).

- 8West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, China (N.L.).

- 9China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China (L.H.).

- 10Yantai Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Yantai, China (Z.Z.).

- 11Shaanxi Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Xi’an, China (T.S.).

- 12The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China (J.F.).

- 13Beijing Fengtai Hospital of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, Beijing, China (Y.D.).

- 14Xi’an TCM Brain Disease Hospital, Xi’an, China (H.S.).

- 15Dongfang Hospital Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China (H.H.).

- 16Luohu District Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shenzhen, China (H.Z.).

- 17Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guiyang, China (Q.M.).

These facts, together with the previously discussed notion that clinical trials from China are notoriously unreliable, do not inspire confidence. Moreover, one might well wonder about the authors’ claim that patients were blinded. As pointed out above, the real and sham acupuncture were fundamentally different: the former did generate de qi, while the latter did not! A slightly pedantic point is my suspicion that the trial did not test the efficacy but the effectiveness of acupuncture, if I am not mistaken. Finally, one might wonder what the rationale of acupuncture as a treatment of CP/CPPS might be. As far as I can see, there is no plausible mechanism (other than placebo) to explain the effects.

So, is the evidence that emerged from the new study convincing?

No, in my view, it is not!

In fact, I am surprised that a journal as reputable as the Annals of Internal Medicine published it.

Recently, I received this comment from a reader:

Edzard-‘I see you do not understand much of trial design’ is true BUT I wager that you are in the same boat when it comes to a design of a trial for LBP treatment: not only you but many other therapists. There are too many variables in the treatment relationship that would allow genuine , valid criticism of any design. If I have to pick one book of the several listed elsewhere I choose Gregory Grieve’s ‘Common Vertebral Joint Problems’. Get it, read it, think about it and with sufficient luck you may come to realize that your warranted prejudices against many unconventional ‘medical’ treatments should not be of the same strength when it comes to judging the physical therapy of some spinal problems as described in the book.

And a chiro added:

EE: I see that you do not understand much of trial design

Perhaps it’s Ernst who doesnt understand how to research back pain.

“The identification of patient subgroups that respond best to specific interventions has been set as a key priority in LBP research for the past 2 decades.2,7 In parallel, surveys of clinicians managing LBP show that there are strong views against generic treatment and an expectation that treatment should be individualized to the patient.6,22.”

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy

Published Online:January 31, 2017Volume47Issue2Pages44-48

Do I need to explain why the Grieve book (yes, I have it and yes, I read it) is not a substitute for evidence that an intervention or technique is effective? No, I didn’t think so. This needs to come from a decent clinical trial.

And how would one design a trial of LBP (low back pain) that would be a meaningful first step and account for the “many variables in the treatment relationship”?

How about proceeding as follows (the steps are not necessarily in that order):

- Study the previously published literature.

- Talk to other experts.

- Recruit a research team that covers all the expertise you need (and don’t have yourself).

- Formulate your research question. Mine would be IS THERAPY XY MORE EFFECTIVE THAN USUAL CARE FOR CHRONIC LBP? I know LBP is but a vague symptom. This does, however, not necessarily matter (see below).

- Define primary and secondary outcome measures, e.g. pain, QoL, function, as well as the validated methods with which they will be quantified.

- Clarify the method you employ for monitoring adverse effects.

- Do a small pilot study.

- Involve a statistician.

- Calculate the required sample size of your study.

- Consider going multi-center with your trial if you are short of patients.

- Define chronic LBP as closely as you can. If there is evidence that a certain type of patient responds better to the therapy xy than others, that might be considered in the definition of the type of LBP.

- List all inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Make sure you include randomization in the design.

- Randomization should be to groups A and B. Group A receives treatment xy, while group B receives usual care.

- Write down what A and B should and should not entail.

- Make sure you include blinding of the outcome assessors and data evaluators.

- Define how frequently the treatments should be administered and for how long.

- Make sure all therapists employed in the study are of a high standard and define the criteria of this standard.

- Train all therapists of both groups such that they provide treatments that are as uniform as possible.

- Work out a reasonable statistical plan for evaluating the results.

- Write all this down in a protocol.

Such a trial design does not need patient or therapist blinding nor does it require a placebo. The information it would provide is, of course, limited in several ways. Yet it would be a rigorous test of the research question.

If the results of the study are positive, one might consider thinking of an adequate sham treatment to match therapy xy and of other ways of firming up the evidence.

As LBP is not a disease but a symptom, the study does not aim to include patients that all are equal in all aspects of their condition. If some patients turn out to respond better than others, one can later check whether they have identifiable characteristics. Subsequently, one would need to do a trial to test whether the assumption is true.

Therapy xy is complex and needs to be tailored to the characteristics of each patient? That is not necessarily an unsolvable problem. Within limits, it is possible to allow each therapist the freedom to chose the approach he/she thinks is optimal. If the freedom needed is considerable, this might change the research question to something like ‘IS THAT TYPE OF THERAPIST MORE EFFECTIVE THAN THOSE EMPLOYING USUAL CARE FOR CHRONIC LBP?’

My trial would obviously not answer all the open questions. Yet it would be a reasonable start for evaluating a therapy that has not yet been submitted to clinical trials. Subsequent trials could build on its results.

I am sure that I have forgotten lots of details. If they come up in discussion, I can try to incorporate them into the study design.