spinal manipulation

We have discussed the tragic case of John Lawler before. Today, the Mail carries a long article about it. Here I merely want to summarise the sequence of events and highlight the role of the GCC.

- In 2017, Mr Lawler, aged 79 at the time, has a history of back problems, including back surgery with metal implants and suffers from pain in his leg.

- His GP recommends to consult a physiotherapist.

- As waiting lists are too long, Mr Lawler sees a chiropractor shortly after his 80th birthday who calls herself ‘doctor’ and who he assumes to be a medic specialising in back pain.

- The chiropractor uses a spinal manipulation of the neck with the drop table.

- There is no evidence that this treatment is effective for pain in the leg.

- No informed consent is obtained from the patient.

- This is acutely painful and brakes the calcified ligaments of Mr Lawler’s upper spine.

- Mr Lawler is immediately paraplegic.

- The chiropractor who had no training in resuscitation is panicked tries mouth to mouth.

- Bending the patient’s neck backwards the chiropractor further compresses his spinal cord.

- When ambulance arrives, the chiropractor misleads the paramedics telling them nothing about a forceful neck manipulation with the drop and suspecting a stroke.

- Thus the paramedics do not stabilise the patient’s neck which could have saved his life.

- Mr Lawler dies the next day in hospital.

- The chiropractor is arrested immediately by the police but then released on bail.

- The expert advising the police is a prominent chiropractor.

- One bail condition is not to practise, pending a hearing by the GCC.

- The GCC decide not to take any action.

- The police therefore release the bail conditions and she goes back to practising.

- The interim suspension hearing of the GCC is being held in September 2017.

- The deceased’s son wants to attend but is not allowed to be present at the hearing even though such events are normally public.

- The coroner’s inquest starts in 2019.

- In November 2019, a coroner rules that Mr Lawler died of respiratory depression.

- The coroner also calls on the GCC to bring in pre-treatment imaging to protect vulnerable patients.

- The GCC announce that they will now continue their inquiry to determine whether or not chiropractor will be struck off the register.

The son of the deceased is today quoted stating that the GCC “seems to be a little self-regulatory chiropractic bubble where chiropractors regulate chiropractors.”

I sympathise with this statement. On this blog, I have repeatedly voiced my concerns about the GCC – see here, for instance – which I therefore do not need to repeat. My opinion of the GCC is also coloured by a personal experience which I will quickly recount now:

A long time ago (I estimate 10 – 15 years), the GCC invited me to give a lecture and I accepted. I do not remember the exact subject they had given me, but I clearly recall elaborating on the risks of spinal manipulation. This was not too well received. When I had finished, a discussion ensued in which I was accused of not knowing my subject and aggressed for daring to ctiticise chiropractic. I had, of couse, given the lecture assuming they wanted to hear my criticism. In the end, I left with the impression that this assumption was wrong and that they really just wanted to lecture, humiliate and punish me for having been a long-term critic of their trade.

I therefore can fully understand of David Lawler’s opinion about the GCC. To me, they certainly behaved as though their aim was not to protect the public, but to defend chiropractors from criticism.

Yes, chiropractic spinal manipulation shows promise to alleviate symptoms of infant colic! At least, this is the result of an overview of systematic reviews of so-called alternative medicines (SCAMs) for infant colic. Here I focus merely on the part that deals with chiropractic spinal manipulation. The authors of the overview come to this result based mainly on the statement:

Spinal manipulation was assessed in six reviews [22, 23, 25,26,27,28]. Two multiple CAM reviews assessed manipulation but did not pool the results [22, 25]. Both found three trials to be effective [68, 69, 72, 73, or] with the exception of one [71].

And here are the references they cite (all the primary studies are on chiropractic manipulation):

22.Perry R, Hunt K, Ernst E. Nutritional supplements and other complementary medicines for infantile colic: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:720–33.

23.Bruyas-Bertholo V, Lachaux A, Dubois J-P, Fourneret P, Letrilliart L. Quels traitements pour les coliques du nourrisson. Presse Med. 2012;41:e404–10.

24.Harb T, Matsuyama M, David M, Hill RJ. Infant colic—what works: a systematic review of interventions for breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(5):668–86.

25.Gutiérrez-Castrellón P, Indrio F, Bolio-Galvis A, et al. Efficacy of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 for infantile colic. Systematic review with network meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(51):e9375.

26.Dobson D, Lucassen PLBJ, Miller JJ, Vlieger AM, Prescott P, Lewith G. Manipulative therapies for infantile colic. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(Issue 12. Art. No.: CD004796)

27.Gleberzon BJ, Arts J, Mei A, McManus EL. The use of spinal manipulative therapy for pediatric health conditions: a systematic review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56(2):128–41.

28.Carnes D, Plunkett A, Ellwood J, et al. Manual therapy for unsettled, distressed and excessively crying infants: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019040.

68.Wiberg J, Nordsteen J, Nilsson N. The short-term effect of spinal manipulation in the treatment of infantile colic: a randomized controlled trial with a blinded observer. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1999;22(8):517–22.

69.Mercer C. A study to determine the efficacy of chiropractic spinal adjustments as a treatment protocol in the Management of Infantile Colic [thesis]. Durban: Technikon Natal,Durban University; 1999.

70.Mercer C, Nook B. The efficacy of chiropractic spinal adjustments as a treatment protocol in the management of infantile colic. In: Presented at: 5th Biennial Congress of the World Federation of Chiropractic. Auckland; 1999. p. 170-1.

71.Olafsdottir E, Forshei S, Fluge G, Markestad T. Randomized controlled trial of infantile colic treated with chiropractic spinal manipulation. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84(2):138–41.

And here is the relevant part of the overview’s conclusion:

Spinal manipulation shows promise to alleviate symptoms of colic, although concerns remain as positive effects were only demonstrated when crying was measured by unblinded parent assessors.

I have several concerns about this new overview:

- My comments on the Canes paper are here and do not need repeating.

- My comments on the Dobson paper (according to the overview authors, it is the best of all the reviews) are also available and need no repeating.

- Reference 22 is a systematic review I did together with the lead author of the new overview while she was one of my co-workers at Exeter. It is not focussed on spinal manipulation, but on all SCAMs. Here is the relevant passage from our conclusions regarding spinal manipulation: The evidence for … manual therapies does not indicate an effect.

How the review authors could come to the verdict that spinal manipulation shows promise is thus more than a little mysterious. If we consider the following, it gets positively bewildering. Even the most rudimentary of searches on Medline will deliver a 2009 systematic review by myself entitled ‘Chiropractic spinal manipulation for infant colic: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials‘. It was the first systematic review on the subject but was not included in the new overview.

Why not?

I do not know.

Here are my conclusions from this paper:

Collectively these RCTs fail to demonstrate that chiropractic spinal manipulation is an effective therapy for infant colic. The largest and best reported study failed to show effectiveness (11). Numerous weaknesses of the primary data would prevent firm conclusions, even if the results of all RCTs had been unanimously positive.

And here is what my review stated about the three primary RCTs assessed in all the other review authors:

The trial by Wiberg et al. (10) did not attempt to blind the infants’ parents who acted as the evaluators of the therapeutic success. The paper provides little details about the recruitment process, but it is fair to assume that patients were asked to participate in a trial of spinal manipulation. Thus one might expect a degree of disappointment in parents of the control group whose children did not receive this treatment. This, in turn, could have impacted on the parents’ subjective judgements. In any case, there is no control for placebo effects which can be very different for a physical intervention compared with an oral placebo – dimethicone was administered as a placebo and the authors stress that it is ‘no better than placebo treatment’.

The RCT by Olafsdottir et al. (11) is by far the best-reported study of all the included RCTs. In many ways, it is a replication of Wiberg’s investigation (10) but on a larger scale with twice the sample size. It is the only study where a serious attempt was made to control for the placebo effects of spinal manipulations. For these reasons, its results seem more reliable than those of the other RCTs.

The RCT by Browning and Miller (12) is a comparison of two manual techniques both of which are assumed by the authors to be effective. Thus it is essentially a non-inferiority trial. Yet, it is woefully underpowered for such a design. Even if it had the necessary power, its results would be difficult to interpret because none of the two interventions have been proven to be effective. Thus, one would still be uncertain whether both interventions are similarly ineffective or effective. As it stands, the result simply seems to demonstrate that symptoms of infant colic lessen over time possibly as a result of non-specific therapeutic effects, the natural history of the disease, concomitant treatments, social desirability or a combination of these factors.

So, what should we conclude from all this? I am not sure – except for one thing, of course: I would not call the evidence for chiropractic spinal manipulation promising.

I have reported previously about the tragic death of John Lawler. Now after the inquest into the events leading to it has concluded, I have the permission to publish the statement of Mr Lawler’s family:

We were devastated to lose John in such tragic and unforeseen circumstances two years ago. A much-loved husband, father and grandfather, he continues to be greatly missed by all of us. Having to re-live the circumstances of his death has been particularly difficult for us but we are grateful to have a clearer picture of the events that led to John’s death. We would like to take this opportunity to thank the coroner’s team, our legal representatives and our wider family and friends for their guidance, empathy and sensitivity throughout this process.

There were several events that went very wrong with John’s chiropractic treatment, before, during, and after the actual manipulation that broke his neck.

Firstly, John thought he was being treated by a medically qualified doctor, when he was not. Furthermore, he had not given informed consent to this treatment.

The chiropractor diagnosed so-called ‘vertebral subluxation complex’ which she aimed to treat by manipulating his neck. We heard this week from medical experts that John had ossified ligaments in his spine, where previously flexible ligaments had turned to bone and become rigid. This condition is not uncommon, and is present in about 10% of those over 50. It would have showed on an X-ray or other imaging technique. The chiropractor did not ask for any images before commencing treatment and was seemingly unaware of the risks of doing a manual manipulation on an elderly patient.

It has become clear that the chiropractor did the manipulation incorrectly, and broke these rigid ligaments during a so-called ‘drop table’ manipulation, causing discs in the cervical spine to rupture and the spinal cord to become crushed. Although these manipulations are done frequently by chiropractors, we have heard that the force applied to his neck by the chiropractor would have had to have been “significant”.

Immediately John reported loss of sensation and paralysis in his arms. At this stage the only safe and appropriate response was to leave him on the treatment bed and await the arrival of the paramedics, and provide an accurate history to the ambulance controller and paramedics. The chiropractor, in fact, manhandled John from the treatment bed into a chair; then tipped his head backwards and gave “mouth to mouth” breaths. She provided an inaccurate and misleading history to the paramedic and ambulance controller, causing the paramedic to treat the incident as “medical” not “traumatic” and to transport John downstairs to the ambulance without stabilising his neck. If the paramedics had been given the full and accurate story, they would have stabilised his neck in situ and transported him on a scoop stretcher – and he would have subsequently survived.

The General Chiropractic Council decided not to suspend the chiropractor from practicing in September 2017. They heard evidence from the chiropractor that she had “not touched the neck during the appointment” and from an expert chiropractor that it would be “physically impossible” for the treatment provided to cause the injury which followed. We have heard this week that this is incorrect. The family was not allowed to attend or give evidence at that hearing, and we are waiting – now 2 years further on – for the GCC to complete their investigations.

We hope that the publicity surrounding this event will highlight the dangers of chiropractic, especially in the elderly and those with already compromised spines. We would again urge the regulator to take immediate measures to ensure that the profession is properly controlled: that chiropractors are prevented from styling themselves as medical professionals; that patients are fully informed and consent to the risks involved; that imaging is done before certain procedures and on high risk clients; and that the limits of the benefits chiropractic can provide are fully explored.

___________________________________________________________________

Before someone comments pointing out that this is merely a single case which does not amount to evidence, let me remind you of the review of cervical manipulation prepared for the Manitoba Health Professions Advisory Council. Here is the abstract:

Neck manipulation or adjustment is a manual treatment where a vertebral joint in the cervical spine—comprised of the 7 vertebrae C1 to C7—is moved by using high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) thrusts that cannot be resisted by the patient. These HVLA thrusts are applied over an individual, restricted joint beyond its physiological limit of motion but within its anatomical limit. The goal of neck manipulation, referred to throughout this report as cervical spine manipulation (CSM), is to restore optimal motion, function, and/or reduce pain. CSM is occasionally utilized by physiotherapists, massage therapists, naturopaths, osteopaths, and physicians, and is the hallmark treatment of chiropractors; however the use of CSM is controversial. This paper aims to thoroughly synthesize evidence from the academic literature regarding the potential risks and benefits of cervical spine manipulation utilizing a rapid literature review method.

METHODS Individual peer-reviewed articles published between January 1990 and November 2016 concerning the safety and efficacy of cervical spine manipulation were identified through MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library.

KEY FINDINGS

- A total of 159 references were identified and cited in this review: 86 case reports/ case series, 37 reviews of the literature, 9 randomized controlled trials, 6 surveys/qualitative studies, 5 case-control studies, 2 retrospective studies, 2 prospective studies and 12 others.

- Serious adverse events following CSM seem to be rare, whereas minor adverse events occur frequently.

- Minor adverse events can include transient neurological symptoms, increased neck pain or stiffness, headache, tiredness and fatigue, dizziness or imbalance, extremity weakness, ringing in the ears, depression or anxiety, nausea or vomiting, blurred or impaired vision, and confusion or disorientation.

- Serious adverse events following CSM can include the following: cerebrovascular injury such as cervical artery dissection, ischemic stroke, or transient ischemic attacks; neurological injury such as damage to nerves or spinal cord (including the dura mater); and musculoskeletal injury including injury to cervical vertebral discs (including herniation, protrusion, or prolapse), vertebrae fracture or subluxation (dislocation), spinal edema, or issues with the paravertebral muscles.

- Rates of incidence of all serious adverse events following CSM range from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in several million cervical spine manipulations, however the literature generally agrees that serious adverse events are likely underreported.

- The best available estimate of incidence of vertebral artery dissection of occlusion attributable to CSM is approximately 1.3 cases for every 100,000 persons <45 years of age receiving CSM within 1 week of manipulative therapy. The current best incidence estimate for vertebral dissection-caused stroke associated with CSM is 0.97 residents per 100,000.

- While CSM is used by manual therapists for a large variety of indications including neck, upper back, and shoulder/arm pain, as well as headaches, the evidence seems to support CSM as a treatment of headache and neck pain only. However, whether CSM provides more benefit than spinal mobilization is still contentious.

- A number of factors may make certain types of patients at higher risk for experiencing an adverse cerebrovascular event after CSM, including vertebral artery abnormalities or insufficiency, atherosclerotic or other vascular disease, hypertension, connective tissue disorders, receiving multiple manipulations in the last 4 weeks, receiving a first CSM treatment, visiting a primary care physician, and younger age. Patients whom have experience prior cervical trauma or neck pain may be at particularly higher risk of experiencing an adverse cerebrovascular event after CSM.

CONCLUSION The current debate around CSM is notably polarized. Many authors stated that the risk of CSM does not outweigh the benefit, while others maintained that CSM is safe—especially in comparison to conventional treatments—and effective for treating certain conditions, particularly neck pain and headache. Because the current state of the literature may not yet be robust enough to inform definitive prohibitory or permissive policies around the application of CSM, an interim approach that balances both perspectives may involve the implementation of a harm-reduction strategy to mitigate potential harms of CSM until the evidence is more concrete. As noted by authors in the literature, approaches might include ensuring manual therapists are providing informed consent before treatment; that patients are provided with resources to aid in early recognition of a serious adverse event; and that regulatory bodies ensure the establishment of consistent definitions of adverse events for effective reporting and surveillance, institute rigorous protocol for identifying high-risk patients, and create detailed guidelines for appropriate application and contraindications of CSM. Most authors indicated that manipulation of the upper cervical spine should be reserved for carefully selected musculoskeletal conditions and that CSM should not be utilized in circumstances where there has not yet been sufficient evidence to establish benefit.

___________________________________________________________________

Just three points which, in my view, sand out most in relation to Mr Lawler’s death:

- Mr Lawler had no proven indication (and at least one very important contra-indication) for neck manipulation.

- He did not give infromed consent.

- The neck manipulation was not within the limits of the physiological range of motion.

The tragic case of John Lawler who died after being treated by a chiropractor has been discussed on this blog before. Naturally, it generated much discussion which, however, left many questions unanswered. Today, I am able to answer some of them.

- Mr Lawler died because of a tear and dislocation of the C4/C5 intervertebral disc caused by considerable external force.

- The pathologist’s report also shows that the deceased’s ligaments holding the vertebrae of the upper spine in place were ossified.

- This is a common abnormality in elderly patients and limits the range of movement of the neck.

- There was no adequately informed consent by Mr Lawler.

- Mr Lawler seemed to have been under the impression that the chiropractor, who used the ‘Dr’ title, was a medical doctor.

- There is no reason to assume that the treatment of Mr Lawler’s neck would be effective for his pain located in his leg.

- The chiropractor used an ‘activator’ which applies only little and well-controlled force. However, she also employed a ‘drop table’ which applies a larger and not well-controlled force.

I have the permission to publish the submissions made to the coroner by the barrister representing the family of Mr Lawler. The barrister’s evidence shows that:

- Chiropractors are not medical doctors and should make this perfectly clear to all of their patients.

- Elderly patients can have several contra-indications to spinal manipulations. They should therefore think twice before consulting a chiropractor.

- A limited range of spinal movement usually is the sign for a chiropractor to intervene. However, this may lead to dramatically bad consequences, if the patient’s para-vertebral ligaments are ossified which happens in about 10% of all elderly individuals.

- Chiropractors are by no means exempt from obtaining informed consent. (In the case of Mr Lawler, this would have had to include the information that the neck manipulation carries serious risks and has not shown to work for any type of pain in the leg and might have saved his life, as he then might have refused to accept the treatment.)

- Chiropractors are not trained to deal with medical emergencies and must leave that to those healthcare professionals who are fully trained.

The Telegraph published an article entitled ‘Crack or quack: what is the truth about chiropractic treatment?’ and is motivated by the story of Mr Lawler, the 80-year-old former bank manager who died after a chiropractic therapy. Here are 10 short quotes from this article which, in the context of this blog and the previous discussions on the Lawler case, are worthy further comment:

1. … [chiropractic] was established in the late 19th century by D.D. Palmer, an American magnetic healer.

“A lot of people don’t realise it’s a form of alternative medicine with some pretty strange beliefs at heart,” says Michael Marshall, project director at the ‘anti-quack’ charity the Good Thinking Society. “Palmer came to believe he was able to cure deafness through the spine, by adjusting it. The theory behind chiropractic is that all disease and ill health is caused by blockages in the flow of energy through the spine, and by adjusting the spine with these grotesque popping sounds, you can remove blockages, allowing the innate energy to flow freely.” Marshall says this doesn’t really chime with much of what we know about human biology…“There is no reason to believe there’s any possible benefit from twisting vertebra. There is no connection between the spine and conditions such as deafness and measles.”…

Michael Marshall is right, chiropractic was built on sand by Palmer who was little more than a charlatan. The problem with this fact is that today’s chiros have utterly failed to leave Palmer’s heritage behind.

2. According to the British Chiropractic Association (BCA), the industry body, “chiropractors are well placed to deliver high quality evidence-based care for back and neck pain.” …

They would say so, wouldn’t they? The BCA has a long history of problems with knowing what high quality evidence-based care is.

3. But it [chiropractic] isn’t always harmless – as with almost any medical treatment, there are possible side effects. The NHS lists these as aches and pains, stiffness, and tiredness; and then mentions the “risk of more serious problems, such as stroke”….

Considering that 50% of patients suffer adverse effects after chiropractic spinal manipulations, this seems somewhat of an understatement.

4. According to one systematic review, spinal manipulation, “particularly when performed on the upper body, is frequently associated with mild to moderate adverse effects. It can also result in serious complications such as vertebral artery dissection followed by stroke.” …

Arterial dissection followed by a stroke probably is the most frequent serious complication. But there are many other risks, as the tragic case of Mr Lawler demonstrates. He had his neck broken by the chiropractor which resulted in paraplegia and death.

5. “There have been virtually hundreds of published cases where neck manipulations have led to vascular accidents, stroke and sometimes death,” says Prof Ernst. “As there is no monitoring system, this is merely the tip of a much bigger iceberg. According to our own UK survey, under-reporting is close to 100 per cent.” …

The call for an effective monitoring system has been loud and clear since many years. It is nothing short of a scandal that chiros have managed to resist it against the best interest of their patients and society at large.

6. Chiropractors are regulated by the General Chiropractic Council (GCC). Marshall says the Good Thinking Society has looked into claims made on chiropractors’ websites, and found that 82 per cent are not compliant with advertising law, for example by saying they can treat colic or by using the misleading term ‘doctor’…

Yes, and that is yet another scandal. It shows how serious chiropractors are about the ‘evidence-based care’ mentioned above.

7. According to GCC guidelines, “if you use the courtesy title ‘doctor’ you must make it clear within the text of any information you put into the public domain that you are not a registered medical practitioner but that you are a ‘Doctor of Chiropractic’.”…

True, and the fact that many chiropractors continue to ignore this demand presenting themselves as doctors and thus misleading the public is the third scandal, in my view.

8. A spokesperson for the BCA said “Chiropractic is a registered primary healthcare profession and a safe form of treatment. In the UK, chiropractors are regulated by law and required to adhere to strict codes of practice, in exactly the same ways as dentists and doctors. Chiropractors are trained to diagnose, treat, manage and prevent disorders of the musculoskeletal system, specialising in neck and back pain.”…

Chiropractors also like to confuse the public by claiming they are primary care physicians. If we understand this term as describing a clinician who is a ‘specialist in Family Medicine, Internal Medicine or Paediatrics who provides definitive care to the undifferentiated patient at the point of first contact, and takes continuing responsibility for providing the patient’s comprehensive care’, we realise that chiropractors fail to fulfil these criteria. The fact that they nevertheless try to mislead the public by calling themselves ‘primary healthcare professionals’ and ‘doctors’ is yet another scandal, in my opinion.

9. The spokesperson said, “medication, routine imaging and invasive surgeries are all commonly used to manage low back pain, despite limited evidence that these methods are effective treatments. Therefore, ensuring there are other options available for patients is paramount.”…

Here the spokesperson misrepresents mainstream medicine to make chiropractic look good. He should know that imaging is used also by chiros for diagnosing back problems (but not for managing them). And he must know that surgery is never used for the type of non-specific back pain that chiros tend to treat. Finally, he should know that exercise is a cheap, safe and effective therapy which is the main conventional option to treat and prevent back pain.

10. According to the European Chiropractors’ Union, “serious harm from chiropractic treatment is extremely rare.”

How do they know, if there is no system to capture cases of adverse effects?

_________________________________________________________

So, what needs to be done? How can we make progress? I think the following five steps would be a good start in the interest of public health:

- Establish an effective monitoring system for adverse effects that is accessible to the public.

- Make sure all chiros are sufficiently well trained to know about the contra-indications of spinal manipulation, including those that apply to elderly patients and infants.

- Change the GCC from a body defending chiros and their interests to one regulating, controlling and, if necessary, reprimanding chiros.

- Make written informed consent compulsory for neck manipulations, and make sure it contains the information that neck manipulations can result in serious harm and are of doubtful efficacy.

- Prevent chiros from making therapeutic claims that are not based on sound evidence.

If these measures had been in place, Mr Lawler might still be alive today.

On 11/11/2019, the York Press reported from coroner’s inquest regarding a chiropractor who allegedly killed a patient. John Lawler suffered a broken neck while being treated by a chiropractor for an aching leg, an inquest has been told. His widow told how her husband was on the treatment table when things started to go wrong. She said he started shouting at chiropractor Dr Arleen Scholten: “You are hurting me. You are hurting me.” Then he began moaning and then said: “I can’t feel my arms.”

Mrs Lawler said Scholten tried to turn him over and then manoeuvred him into a chair next to the treatment table but he had become unresponsive. “He was like a rag doll,” she said. “His lips looked a little bit blue but I knew he was breathing. “I said ‘Has he had a stroke?’ She put his head back and said ‘no, his features are symmetrical’.

When the paramedics arrived, they treated Mr Lawler and to hospital. He had an MRI scan and a doctor told Mrs Lawler that he had suffered a broken neck. She was then informed that her husband was a paraplegic and he could undergo a 14 hour operation which would be traumatic but even before that could happen he “faded away” and died.

__________________________________________

There are, as far as I can see, four issues of interest here:

- It could be that Mr Lawler had osteoporosis; we will no doubt hear about this in the course of the inquest. If so, normal force could have led to the fracture, and the chiropractor would claim that she is not to blame for the fracture and the subsequent death of her patient. The question then would be whether she was under an obligation to check whether, in a man of Mr Lawler’s age, his bone density was normal or whether she could just assume that it was. In my view, any clinician applying a potentially harmful therapy has the obligation to make sure there are no contra-indications to it. If that all is so, the chiropractor might have been both negligent and reckless.

- Has neck manipulation been shown to be effective for any type of pain in the leg? That’s an easy one: No!

- Has the chiropractor obtained informed consent from her patient before commencing the treatment? The inquest will no doubt verify this. As many chiropractors fail to do it, I would not be too surprised if, in the present case, this was also not done. Should that be so, the chiropractor would have been negligent.

- One might be surprised to hear that the chiropractor manipulated the neck of a patient who consulted her not because of neck pain but because of a condition seemingly unrelated to the neck. This is an issue that comes up regularly and which is therefore importan; some people might be aware that it is dangerous to see a chiropractor when suffering from neck pain because he/she is bound to manipulate the neck. By contrast, most people would probably think it is ok to consult a chiropractor when suffering from lower back pain, because manipulations in that region is far less risky. The truth, however, is that chiropractors have been taught that the spine is one organ and one entity. Thus they tend to check for subluxations (or whatever name they give to the non-existing condition they all aim to treat) in every region of the spine. If they find one in the neck – and they usually do – they would ‘adjust’ it, meaning they would apply one or more high-velocity, low-amplitude thrusts and manipulate the neck. This could well be, I think, how the chiropractor in the case that is before the court at present came to manipulate the neck of her patient. And this might be how poor Mr Lawler lost his life.

Is there a lesson to be learnt from this tragic case?

Yes, I think there is: if you want to make sure that a chiropractor does not break your neck, don’t go and consult one – whatever your health problem happens to be.

Spinal epidural haematoma is a potentially serious condition that can occur due to trauma, such as spinal manipulation, particularly in the presence of a blood clotting abnormality. A case has been published of a patient who, after performing self-neck manipulation, suffered spinal epidural haematoma and subsequent paralysis of all 4 limbs.

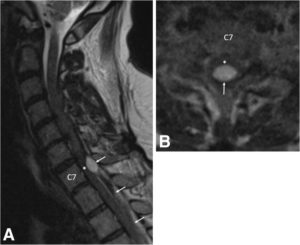

A 63-year-old man presented to the emergency department with worsening inter-scapular pain radiating to his neck one day after performing self-manipulation of his cervical spine. He was anti-coagulated with warfarin therapy for the management of his atrial fibrillation. Approximately 48 h after the manipulation, the patient became acutely quadriparetic and hypotensive. Urgent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a multilevel spinal epidural haematoma from the lower cervical to thoracic spine.

a Pre-operative sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the cervical spine demonstrates an epidural hematoma (arrows) with the cranial extent at the C6/7 level. The hematoma is mixed signal intensity, consistent with various stages of bleeding. Severe spinal cord (asterisk) compression is present at the C7 level. b Pre-operative axial T2-weighted MRI at the C7 level demonstrates a loculated epidural hematoma (arrow) compressing the spinal cord (asterisk). Due to the urgent nature of the MRI, image quality is degraded

With identification of an active bleed and an INR remaining close to 7.0, the patient’s hypercoaguable state was reversed prior to emergency surgery. The patient underwent partial C7, complete T1 and T2, and partial T3 bilateral laminectomy for evacuation of haematoma. Placement of an epidural drainage catheter was also performed.

During the first 6 days following surgery, the patient recovered some function of the upper and lower extremities while undergoing hospital-based physical therapy. Post-operative MRI showed resolution of the haematoma and cord compression without resultant cord damage.

The patient completed a 2-week course of acute interdisciplinary rehabilitation. The epidural drainage catheter remained in place for most of his post-operative stay. His neurogenic bladder with urinary retention resolved. At hospital discharge, the patient’s greatest deficits remained his fine motor skills to his right hand along with residual paraesthesia in his lower extremities. He also exhibited mild dyspraxia with finger-to-nose testing on the right and heel-to-shin testing bilaterally. The patient regained full manual muscle strength of all 4 extremities and ultimately returned to his baseline functional status, which included ambulating independently with a cane and independence with activities of daily living.

The authors concluded that partial C7, complete T1 and T2, and partial T3 bilateral laminectomy was performed for evacuation of the spinal epidural hematoma. Following a 2-week course of acute inpatient rehabilitation, the patient returned to his baseline functional status. This case highlights the risks of self-manipulation of the neck and potentially other activities that significantly stretch or apply torque to the cervical spine. It also presents a clinical scenario in which practitioners of spinal manipulation therapy should be aware of patients undergoing anticoagulation therapy.

In the present case, the spinal manipulation was self-inflicted. Usually it is performed by a chiropractor, and there are published case reports where chiropractic spinal manipulations have caused epidural haematoma. No matter who does this treatment, it is, I think, wise to consider the fact that the risks of spinal manipulations do not demonstrably outweigh its benefits.

This systematic review was aimed at investigating the current evidence to determine whether there is an association between chiropractic use and opioid receipt.

Controlled studies, cohort studies, and case-control studies including adults with noncancer pain were eligible for inclusion. Studies reporting opioid receipt for both subjects who used chiropractic care and nonusers were included. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment were completed independently by pairs of reviewers. Meta-analysis was performed and presented as an odds ratio with 95% confidence interval.

In all, 874 articles were identified. After detailed selection, 26 articles were reviewed in full, and 6 met the inclusion criteria. Five studies focused on back pain and one on neck pain. The prevalence of chiropractic care among patients with spinal pain varied between 11.3% and 51.3%. The proportion of patients receiving an opioid prescription was lower for chiropractic users (range = 12.3-57.6%) than nonusers (range = 31.2-65.9%). In a random-effects analysis, chiropractic users had a 64% lower odds of receiving an opioid prescription than nonusers (odds ratio = 0.36, 95% confidence interval = 0.30-0.43, P < 0.001, I2 = 92.8%).

The authors concluded that this review demonstrated an inverse association between chiropractic use and opioid receipt among patients with spinal pain. Further research is warranted to assess this association and the implications it may have for case management strategies to decrease opioid use.

These results are in line with a previous study showing that among New Hampshire adults with office visits for noncancer low-back pain, the likelihood of filling a prescription for an opioid analgesic was significantly lower for recipients of services delivered by doctors of chiropractic compared with nonrecipients. The underlying cause of this correlation remains unknown, indicating the need for further investigation.

The question is: what do such findings tell us?

I have no doubt that chiropractors will claim that using their services will reduce the opioid problem. But this is, of course, wishful thinking. The thing that will reduce it is not more chiro use but quite simply less opioid use!

The important thing to remember here is CORRELATION IS NOT CAUSATION!

People who drive a VW car are less likely to buy a Mercedes.

People who have ordered fish in a restaurant are unlikely to also order a steak.

People who use physiotherapy for back pain will probably use less opioids than those who don’t consult physios.

People who treat their back pain with massage therapy are less likely to also use opioids.

Etc.

Etc.

This is all very obvious, self-evident and perhaps even boring.

The most interesting finding here is in my view the fact that 31.2-65.9% of patients using chiropractic for their neck/back pain also took opioids. This seems to confirm what we often have discussed before:

CHIROPRACTIC TREATMENT IS NOT NEARLY AS EFFECTIVE AS CHIROS WANT US TO BELIEVE.

Spinal manipulation is a treatment employed by several professions, including physiotherapists and osteopaths; for chiropractors, it is the hallmark therapy.

- They use it for (almost) every patient.

- They use it for (almost) every condition.

- They have developed most of the techniques.

- Spinal manipulation is the focus of their education and training.

- All textbooks of chiropractic focus on spinal manipulation.

- Chiropractors are responsible for most of the research on spinal manipulation.

- Chiropractors are responsible for most of the adverse effects of spinal manipulation.

Spinal manipulation has traditionally involved an element of targeting the technique to a level of the spine where the proposed movement dysfunction is sited. This study evaluated the effects of a targeted manipulative thrust versus a thrust applied generally to the lumbar region.

Sixty patients with low back pain were randomly allocated to two groups: one group received a targeted manipulative thrust (n=29) and the other a general manipulation thrust (GT) (n=31) to the lumbar spine. Thrust was either localised to a clinician-defined symptomatic spinal level or an equal force was applied through the whole lumbosacral region. The investigators measured pressure-pain thresholds (PPTs) using algometry and muscle activity (magnitude of stretch reflex) via surface electromyography. Numerical ratings of pain and Oswestry Disability Index scores were collected.

Repeated measures of analysis of covariance revealed no between-group differences in self-reported pain or PPT for any of the muscles studied. The authors concluded that a GT procedure—applied without any specific targeting—was as effective in reducing participants’ pain scores as targeted approaches.

The authors point out that their data are similar to findings from a study undertaken with a younger, military sample, showing no significant difference in pain response to a general versus specific rotation, manipulation technique. They furthermore discuss that, if ‘targeted’ manipulation proves to be no better than ‘general’ manipulation (when there has been further research, more studies), it would challenge the need for some current training courses that involve comprehensive manual skill training and teaching of specific techniques. If simple SM interventions could be delivered with less training, than the targeted approach currently requires, it would mean a greater proportion of the population who have back pain could access those general manipulation techniques.

Assuming that the GT used in this trial was equivalent to a placebo control, another interpretation of these results is that the effects of spinal manipulation are largely or even entirely due to a placebo response. If this were confirmed in further studies, it would be yet one more point to argue that spinal manipulation is not a treatment of choice for back pain or any other condition.

A systematic review of the evidence for effectiveness and harms of specific spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) techniques for infants, children and adolescents has been published by Dutch researchers. I find it important to stress from the outset that the authors are not affiliated with chiropractic institutions and thus free from such conflicts of interest.

They searched electronic databases up to December 2017. Controlled studies, describing primary SMT treatment in infants (<1 year) and children/adolescents (1–18 years), were included to determine effectiveness. Controlled and observational studies and case reports were included to examine harms. One author screened titles and abstracts and two authors independently screened the full text of potentially eligible studies for inclusion. Two authors assessed risk of bias of included studies and quality of the body of evidence using the GRADE methodology. Data were described according to PRISMA guidelines and CONSORT and TIDieR checklists. If appropriate, random-effects meta-analysis was performed.

Of the 1,236 identified studies, 26 studies were eligible. In all but 3 studies, the therapists were chiropractors. Infants and children/adolescents were treated for various (non-)musculoskeletal indications, hypothesized to be related to spinal joint dysfunction. Studies examining the same population, indication and treatment comparison were scarce. Due to very low quality evidence, it is uncertain whether gentle, low-velocity mobilizations reduce complaints in infants with colic or torticollis, and whether high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulations reduce complaints in children/adolescents with autism, asthma, nocturnal enuresis, headache or idiopathic scoliosis. Five case reports described severe harms after HVLA manipulations in 4 infants and one child. Mild, transient harms were reported after gentle spinal mobilizations in infants and children, and could be interpreted as side effect of treatment.

The authors concluded that, based on GRADE methodology, we found the evidence was of very low quality; this prevented us from drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of specific SMT techniques in infants, children and adolescents. Outcomes in the included studies were mostly parent or patient-reported; studies did not report on intermediate outcomes to assess the effectiveness of SMT techniques in relation to the hypothesized spinal dysfunction. Severe harms were relatively scarce, poorly described and likely to be associated with underlying missed pathology. Gentle, low-velocity spinal mobilizations seem to be a safe treatment technique in infants, children and adolescents. We encourage future research to describe effectiveness and safety of specific SMT techniques instead of SMT as a general treatment approach.

We have often noted that, in chiropractic trials, harms are often not mentioned (a fact that constitutes a violation of research ethics). This was again confirmed in the present review; only 4 of the controlled clinical trials reported such information. This means harms cannot be evaluated by reviewing such studies. One important strength of this review is that the authors realised this problem and thus included other research papers for assessing the risks of SMT. Consequently, they found considerable potential for harm and stress that under-reporting remains a serious issue.

Another problem with SMT papers is their often very poor methodological quality. The authors of the new review make this point very clearly and call for more rigorous research. On this blog, I have repeatedly shown that research by chiropractors resembles more a promotional exercise than science. If this field wants to ever go anywhere, if needs to adopt rigorous science and forget about its determination to advance the business of chiropractors.

I feel it is important to point out that all of this has been known for at least one decade (even though it has never been documented so scholarly as in this new review). In fact, when in 2008, my friend and co-author Simon Singh, published that chiropractors ‘happily promote bogus treatments’ for children, he was sued for libel. Since then, I have been legally challenged twice by chiropractors for my continued critical stance on chiropractic. So, essentially nothing has changed; I certainly do not see the will of leading chiropractic bodies to bring their house in order.

May I therefore once again suggest that chiropractors (and other spinal manipulators) across the world, instead of aggressing their critics, finally get their act together. Until we have conclusive data showing that SMT does more good than harm to kids, the right thing to do is this: BEHAVE LIKE ETHICAL HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS: BE HONEST ABOUT THE EVIDENCE, STOP MISLEADING PARENTS AND STOP TREATING THEIR CHILDREN!