pseudo-science

Proof of Principle or Concept studies are investigations usually for an early stage of clinical drug development when a compound has shown potential in animal models and early safety testing. This step often links between Phase-I and dose ranging Phase-II studies. These small-scale studies are designed to detect a signal that the drug is active on a patho-physiologically relevant mechanism, as well as preliminary evidence of efficacy in a clinically relevant endpoint.

For therapies that have been in use for many years, proof of concept studies are unusual to say the least. A proof of concept study of osteopathy has never been heard of. This is why I was fascinated by this new paper. The objective of this ‘proof of concept’ study was to evaluate the effect of osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMTh) on chronic symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Patients (n=22) with MS received 5 forty-minute MS health education sessions (control group) or 5 OMTh sessions (OMTh group). All participants completed a questionnaire that assessed their level of clinical disability, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and quality of life before the first session, one week after the final session, and 6 months after the final session. The Extended Disability Status Scale, a modified Fatigue Impact Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory-II, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the 12-item Short Form Health Survey were used to assess clinical disability, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and quality of life, respectively. In the OMTh group, statistically significant improvements in fatigue and depression were found one week after the final session. A non-significant increase in quality of life was also found in the OMTh group one week after the final session.

The authors concluded that the results demonstrate that OMTh should be considered in the treatment of patients with chronic symptoms of MS.

Who said that reading alternative medicine research papers is not funny? I for one laughed heartily when I read this (no need at all to go into the many obvious flaws of the study). Calling a pilot study ‘proof of concept’ is certainly not without hilarity. Drawing definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of OMTh is outright laughable. But issuing a far-reaching recommendation for use of OMTh in MS is just better than the best comedy. This had me in stiches!

I congratulate the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association and the international team of authors for providing us with such fun.

Osteopathy is a form of manual therapy invented by the American Andrew Taylor Still (1828-1917). Today, US osteopaths (doctors of osteopathy or DOs) practise no or little manual therapy; they are fully recognised as medical doctors who can specialise in any medical field after their training which is almost identical with that of MDs. Outside the US, osteopaths practice almost exclusively manual treatments and are considered alternative practitioners. This post deals with the latter category of osteopaths.

Still defined his original osteopathy as a science which consists of such exact, exhaustive, and verifiable knowledge of the structure and function of the human mechanism, anatomical, physiological and psychological, including the chemistry and physics of its known elements, as has made discoverable certain organic laws and remedial resources, within the body itself, by which nature under the scientific treatment peculiar to osteopathic practice, apart from all ordinary methods of extraneous, artificial, or medicinal stimulation, and in harmonious accord with its own mechanical principles, molecular activities, and metabolic processes, may recover from displacements, disorganizations, derangements, and consequent disease, and regained its normal equilibrium of form and function in health and strength.

Based on such vague and largely nonsensical statements, traditional osteopaths feel entitled to offer treatments for most human diseases, conditions and symptoms. The studies they produce to back up their claims tend to be as poor as Still’s original assumptions were fantastic.

Here is an apt example:

The aim of this new study was to study the effect of osteopathic manipulation on pain relief and quality of life improvement in hospitalized oncology geriatric patients.

The researchers conducted a non-randomized controlled clinical trial with 23 cancer patients. They were allocated to two groups: the study group (OMT [osteopathic manipulative therapy] group, N = 12) underwent OMT in addition to physiotherapy (PT), while the control group (PT group, N = 12) underwent only PT. Included were postsurgical cancer patients, male and female, age ⩾65 years, with an oncology prognosis of 6 to 24 months and chronic pain for at least 3 months with an intensity score higher than 3, measured with the Numeric Rating Scale. Exclusion criteria were patients receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment at the time of the study, with mental disorders (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] = 10-20), with infection, anticoagulation therapy, cardiopulmonary disease, or clinical instability post-surgery. Oncology patients were admitted for rehabilitation after cancer surgery. The main cancers were colorectal cancer, osteosarcoma, spinal metastasis from breast and prostatic cancer, and kidney cancer.

The OMT, based on osteopathic principles of body unit, structure-function relationship, and homeostasis, was designed for each patient on the basis of the results of the osteopathic examination. Diagnosis and treatment were founded on 5 models: biomechanics, neurologic, metabolic, respiratory-circulatory, and behaviour. The OMT protocol was administered by an osteopath with clinical experience of 10 years in one-on-one individual sessions. The techniques used were: dorsal and lumbar soft tissue, rib raising, back and abdominal myofascial release, cervical spine soft tissue, sub-occipital decompression, and sacroiliac myofascial release. Back and abdominal myofascial release techniques are used to improve back movement and internal abdominal pressure. Sub-occipital decompression involves traction at the base of the skull, which is considered to release restrictions around the vagus nerve, theoretically improving nerve function. Sacroiliac myofascial release is used to improve sacroiliac joint movement and to reduce ligament tension. Strain-counter-strain and muscle energy technique are used to diminish the presence of trigger points and their pain intensity. OMT was repeated once every week during 4 weeks for each group, for a total of 4 treatments. Each treatment lasted 45 minutes.

At enrolment (T0), the patients were evaluated for pain intensity and quality of life by an external examiner. All patients were re-evaluated every week (T1, T2, T3, and T4) for pain intensity, and at the end of the study treatment (T4) for quality of life.

The OMT added to physiotherapy produced a significant reduction in pain both at T2 and T4. The difference in quality of life improvements between T0 and T4 was not statistically significant. Pain improved in the PT group at T4. Between-group analysis of pain and quality of life did not show any significant difference between the two treatments.

The authors concluded that our study showed a significant improvement in pain relief and a nonsignificant improvement in quality of life in hospitalized geriatric oncology patients during osteopathic manipulative treatment.

GOOD GRIEF!

Where to begin?

Even if there had been a difference in outcome between the two groups, such a finding would not have shown an effect of OMT per se. More likely, it would have been due to the extra attention and the expectation in the OMT group (or caused by the lack of randomisation). The A+B vs B design used for this study does not control for non-specific effects. Therefore it is incapable of establishing a causal relationship between the therapy and the outcome.

As it turns out, there were no inter-group differences. How can this be? I have often stated that A+B is always more than B alone. And this is surely true!

So, how can I explain this?

As far as I can see, there are two possibilities:

- The study was underpowered, and thus an existing difference was not picked up.

- The OMT had a detrimental effect on the outcome measures thus neutralising the positive effects of the extra attention and expectation.

And which possibility does apply in this case?

Nobody can know from these data.

Integrative Cancer Therapies, the journal that published this paper, states that it focuses on a new and growing movement in cancer treatment. The journal emphasizes scientific understanding of alternative and traditional medicine therapies, and the responsible integration of both with conventional health care. Integrative care includes therapeutic interventions in diet, lifestyle, exercise, stress care, and nutritional supplements, as well as experimental vaccines, chrono-chemotherapy, and other advanced treatments. I feel that the editors should rather focus more on the quality of the science they publish.

My conclusion from all this is the one I draw so depressingly often: fatally flawed science is not just useless, it is unethical, gives clinical research a bad name, hinders progress, and can be harmful to patients.

I remember reading this paper entitled ‘Comparison of acupuncture and other drugs for chronic constipation: A network meta-analysis’ when it first came out. I considered discussing it on my blog, but then decided against it for a range of reasons which I shall explain below. The abstract of the original meta-analysis is copied below:

The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and side effects of acupuncture, sham acupuncture and drugs in the treatment of chronic constipation. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of acupuncture and drugs for chronic constipation were comprehensively retrieved from electronic databases (such as PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, CNKI, Wanfang Database, VIP Database and CBM) up to December 2017. Additional references were obtained from review articles. With quality evaluations and data extraction, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was performed using a random-effects model under a frequentist framework. A total of 40 studies (n = 11032) were included: 39 were high-quality studies and 1 was a low-quality study. NMA showed that (1) acupuncture improved the symptoms of chronic constipation more effectively than drugs; (2) the ranking of treatments in terms of efficacy in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome was acupuncture, polyethylene glycol, lactulose, linaclotide, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, prucalopride, sham acupuncture, tegaserod, and placebo; (3) the ranking of side effects were as follows: lactulose, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, polyethylene glycol, prucalopride, linaclotide, placebo and tegaserod; and (4) the most commonly used acupuncture point for chronic constipation was ST25. Acupuncture is more effective than drugs in improving chronic constipation and has the least side effects. In the future, large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to prove this. Sham acupuncture may have curative effects that are greater than the placebo effect. In the future, it is necessary to perform high-quality studies to support this finding. Polyethylene glycol also has acceptable curative effects with fewer side effects than other drugs.

END OF 1st QUOTE

This meta-analysis has now been retracted. Here is what the journal editors have to say about the retraction:

After publication of this article [1], concerns were raised about the scientific validity of the meta-analysis and whether it provided a rigorous and accurate assessment of published clinical studies on the efficacy of acupuncture or drug-based interventions for improving chronic constipation. The PLOS ONE Editors re-assessed the article in collaboration with a member of our Editorial Board and noted several concerns including the following:

- Acupuncture and related terms are not mentioned in the literature search terms, there are no listed inclusion or exclusion criteria related to acupuncture, and the outcome measures were not clearly defined in terms of reproducible clinical measures.

- The study included acupuncture and electroacupuncture studies, though this was not clearly discussed or reported in the Title, Methods, or Results.

- In the “Routine paired meta-analysis” section, both acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups were reported as showing improvement in symptoms compared with placebo. This finding and its implications for the conclusions of the article were not discussed clearly.

- Several included studies did not meet the reported inclusion criteria requiring that studies use adult participants and assess treatments of >2 weeks in duration.

- Data extraction errors were identified by comparing the dataset used in the meta-analysis (S1 Table) with details reported in the original research articles. Errors included aspects of the study design such as the experimental groups included in the study, the number of study arms in the trial, number of participants, and treatment duration. There are also several errors in the Reference list.

- With regard to side effects, 22 out of 40 studies were noted as having reported side effects. It was not made clear whether side effects were assessed as outcome measures for the other 18 studies, i.e. did the authors collect data clarifying that there were no side effects or was this outcome measure not assessed or reported in the original article. Without this clarification the conclusion comparing side effect frequencies is not well supported.

- The network geometry presented in Fig 5 is not correct and misrepresents some of the study designs, for example showing two-arm studies as three-arm studies.

- The overall results of the meta-analysis are strongly reliant on the evidence comparing acupuncture versus lactulose treatment. Several of the trials that assessed this comparison were poorly reported, and the meta-analysis dataset pertaining to these trials contained data extraction errors. Furthermore, potential bias in studies assessing lactulose efficacy in acupuncture trials versus lactulose efficacy in other trials was not sufficiently addressed.

While some of the above issues could be addressed with additional clarifications and corrections to the text, the concerns about study inclusion, the accuracy with which the primary studies’ research designs and data were represented in the meta-analysis, and the reporting quality of included studies directly impact the validity and accuracy of the dataset underlying the meta-analysis. As a consequence, we consider that the overall conclusions of the study are not reliable. In light of these issues, the PLOS ONE Editors retract the article. We apologize that these issues were not adequately addressed during pre-publication peer review.

LZ disagreed with the retraction. YM and XD did not respond.

END OF 2nd QUOTE

Let me start by explaining why I initially decided not to discuss this paper on my blog. Already the first sentence of the abstract put me off, and an entire chorus of alarm-bells started ringing once I read further.

- A meta-analysis is not a ‘study’ in my book, and I am somewhat weary of researchers who employ odd or unprecise language.

- We all know (and I have discussed it repeatedly) that studies of acupuncture frequently fail to report adverse effects (in doing this, their authors violate research ethics!). So, how can it be a credible aim of a meta-analysis to compare side-effects in the absence of adequate reporting?

- The methodology of a network meta-analysis is complex and I know not a lot about it.

- Several things seemed ‘too good to be true’, for instance, the funnel-plot and the overall finding that acupuncture is the best of all therapeutic options.

- Looking at the references, I quickly confirmed my suspicion that most of the primary studies were in Chinese.

In retrospect, I am glad I did not tackle the task of criticising this paper; I would probably have made not nearly such a good job of it as PLOS ONE eventually did. But it was only after someone raised concerns that the paper was re-reviewed and all the defects outlined above came to light.

While some of my concerns listed above may have been trivial, my last point is the one that troubles me a lot. As it also related to dozens of Cochrane reviews which currently come out of China, it is worth our attention, I think. The problem, as I see it, is as follows:

- Chinese (acupuncture, TCM and perhaps also other) trials are almost invariably reporting positive findings, as we have discussed ad nauseam on this blog.

- Data fabrication seems to be rife in China.

- This means that there is good reason to be suspicious of such trials.

- Many of the reviews that currently flood the literature are based predominantly on primary studies published in Chinese.

- Unless one is able to read Chinese, there is no way of evaluating these papers.

- Therefore reviewers of journal submissions tend to rely on what the Chinese review authors write about the primary studies.

- As data fabrication seems to be rife in China, this trust might often not be justified.

- At the same time, Chinese researchers are VERY keen to publish in top Western journals (this is considered a great boost to their career).

- The consequence of all this is that reviews of this nature might be misleading, even if they are published in top journals.

I have been struggling with this problem for many years and have tried my best to alert people to it. However, it does not seem that my efforts had even the slightest success. The stream of such reviews has only increased and is now a true worry (at least for me). My suspicion – and I stress that it is merely that – is that, if one would rigorously re-evaluate these reviews, their majority would need to be retracted just as the above paper. That would mean that hundreds of papers would disappear because they are misleading, a thought that should give everyone interested in reliable evidence sleepless nights!

So, what can be done?

Personally, I now distrust all of these papers, but I admit, that is not a good, constructive solution. It would be better if Journal editors (including, of course, those at the Cochrane Collaboration) would allocate such submissions to reviewers who:

- are demonstrably able to conduct a CRITICAL analysis of the paper in question,

- can read Chinese,

- have no conflicts of interest.

In the case of an acupuncture review, this would narrow it down to perhaps just a handful of experts worldwide. This probably means that my suggestion is simply not feasible.

But what other choice do we have?

One could oblige the authors of all submissions to include full and authorised English translations of non-English articles. I think this might work, but it is, of course, tedious and expensive. In view of the size of the problem (I estimate that there must be around 1 000 reviews out there to which the problem applies), I do not see a better solution.

(I would truly be thankful, if someone had a better one and would tell us)

Psoriasis is one of those conditions that is

- chronic,

- not curable,

- irritating to the point where it reduces quality of life.

In other words, it is a disease for which virtually all alternative treatments on the planet are claimed to be effective. But which therapies do demonstrably alleviate the symptoms?

This review (published in JAMA Dermatology) compiled the evidence on the efficacy of the most studied complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities for treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis and discusses those therapies with the most robust available evidence.

PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov searches (1950-2017) were used to identify all documented CAM psoriasis interventions in the literature. The criteria were further refined to focus on those treatments identified in the first step that had the highest level of evidence for plaque psoriasis with more than one randomized clinical trial (RCT) supporting their use. This excluded therapies lacking RCT data or showing consistent inefficacy.

A total of 457 articles were found, of which 107 articles were retrieved for closer examination. Of those articles, 54 were excluded because the CAM therapy did not have more than 1 RCT on the subject or showed consistent lack of efficacy. An additional 7 articles were found using references of the included studies, resulting in a total of 44 RCTs (17 double-blind, 13 single-blind, and 14 nonblind), 10 uncontrolled trials, 2 open-label nonrandomized controlled trials, 1 prospective controlled trial, and 3 meta-analyses.

Compared with placebo, application of topical indigo naturalis, studied in 5 RCTs with 215 participants, showed significant improvements in the treatment of psoriasis. Treatment with curcumin, examined in 3 RCTs (with a total of 118 participants), 1 nonrandomized controlled study, and 1 uncontrolled study, conferred statistically and clinically significant improvements in psoriasis plaques. Fish oil treatment was evaluated in 20 studies (12 RCTs, 1 open-label nonrandomized controlled trial, and 7 uncontrolled studies); most of the RCTs showed no significant improvement in psoriasis, whereas most of the uncontrolled studies showed benefit when fish oil was used daily. Meditation and guided imagery therapies were studied in 3 single-blind RCTs (with a total of 112 patients) and showed modest efficacy in treatment of psoriasis. One meta-analysis of 13 RCTs examined the association of acupuncture with improvement in psoriasis and showed significant improvement with acupuncture compared with placebo.

The authors concluded that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis are indigo naturalis, curcumin, dietary modification, fish oil, meditation, and acupuncture. This review will aid practitioners in advising patients seeking unconventional approaches for treatment of psoriasis.

I am sorry to say so, but this review smells fishy! And not just because of the fish oil. But the fish oil data are a good case in point: the authors found 12 RCTs of fish oil. These details are provided by the review authors in relation to oral fish oil trials: Two double-blind RCTs (one of which evaluated EPA, 1.8g, and DHA, 1.2g, consumed daily for 12 weeks, and the other evaluated EPA, 3.6g, and DHA, 2.4g, consumed daily for 15 weeks) found evidence supporting the use of oral fish oil. One open-label RCT and 1 open-label non-randomized controlled trial also showed statistically significant benefit. Seven other RCTs found lack of efficacy for daily EPA (216mgto5.4g)or DHA (132mgto3.6g) treatment. The remainder of the data supporting efficacy of oral fish oil treatment were based on uncontrolled trials, of which 6 of the 7 studies found significant benefit of oral fish oil. This seems to support their conclusion. However, the authors also state that fish oil was not shown to be effective at several examined doses and duration. Confused? Yes, me too!

Even more confusing is their failure to mention a single trial of Mahonia aquifolium. A 2013 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Dermatology included 5 RCTs of Mahonia aquifolium which, according to these authors, provided ‘limited support’ for its effectiveness. How could they miss that?

More importantly, how could the reviewers miss to conduct a proper evaluation of the quality of the studies they included in their review (even in their abstract, they twice speak of ‘robust evidence’ – but how can they without assessing its robustness? [quantity is not remotely the same as quality!!!]). Without a transparent evaluation of the rigour of the primary studies, any review is nearly worthless.

Take the 12 acupuncture trials, for instance, which the review authors included based not on an assessment of the studies but on a dodgy review published in a dodgy journal. Had they critically assessed the quality of the primary studies, they could have not stated that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis …[include]… acupuncture. Instead they would have had to admit that these studies are too dubious for any firm conclusion. Had they even bothered to read them, they would have found that many are in Chinese (which would have meant they had to be excluded in their review [as many pseudo-systematic reviewers, the authors only considered English papers]).

There might be a lesson in all this – well, actually I can think of at least two:

- Systematic reviews might well be the ‘Rolls Royce’ of clinical evidence. But even a Rolls Royce needs to be assembled correctly, otherwise it is just a heap of useless material.

- Even top journals do occasionally publish poor-quality and thus misleading reviews.

If you thought that Chinese herbal medicine is just for oral use, you were wrong. This article explains it all in some detail: Injections of traditional Chinese herbal medicines are also referred to as TCM injections. This approach has evolved during the last 70 years as a treatment modality that, according to the authors, parallels injections of pharmaceutical products.

The researchers from China try to provide a descriptive analysis of various aspects of TCM injections. They used the the following data sources: (1) information retrieved from website of drug registration system of China, and (2) regulatory documents, annual reports and ADR Information Bulletins issued by drug regulatory authority.

As of December 31, 2017, 134 generic names for TCM injections from 224 manufacturers were approved for sale. Only 5 of the 134 TCM injections are documented in the present version of Ch.P (2015). Most TCM injections are documented in drug standards other than Ch.P. The formulation, ingredients and routes of administration of TCM injections are more complex than conventional chemical injections. Ten TCM injections are covered by national lists of essential medicine and 58 are covered by China’s basic insurance program of 2017. Adverse drug reactions (ADR) reports related to TCM injections account for over 50% of all ADR reports related to TCMs, and the percentages have been rising annually.

The authors concluded that making traditional medicine injectable might be a promising way to develop traditional medicines. However, many practical challenges need to be overcome by further development before a brighter future for injectable traditional medicines can reasonably be expected.

I have to admit that TCM injections frighten the hell out of me. I feel that before we inject any type of substance into patients, we ought to know as a bare minimum:

- for what conditions, if any, they have been proven to be efficacious,

- what adverse effects each active ingredient can cause,

- with what other drugs they might interact,

- how reliable the quality control for these injections is.

I somehow doubt that these issues have been fully addressed in China. Therefore, I can only hope the Chinese manufacturers are not planning to export their dubious TCM injections.

This could (and perhaps should) be a very short post:

I HAVE NO QUALIFICATIONS IN HOMEOPATHY!

NONE!!!

[the end]The reason why it is not quite as short as that lies in the the fact that homeopathy-fans regularly start foaming from the mouth when they state, and re-state, and re-state, and re-state this simple, undeniable fact.

The latest example is by our friend Barry Trestain who recently commented on this blog no less than three times about the issue:

- Falsified? You didn’t have any qualifications falsified or otherwise according to this. In quotes as well lol. Perhaps you could enlighten us all on this. Edzard Ernst, Professor of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) at Exeter University, is the most frequently cited „expert‟ by critics of homeopathy, but a recent interview has revealed the astounding fact that he “never completed any courses” and has no qualifications in homeopathy. What is more his principal experience in the field was when “After my state exam I worked under Dr Zimmermann at the Münchner Krankenhaus für Naturheilweisen” (Munich Hospital for Natural Healing Methods). Asked if it is true that he only worked there “for half a year”, he responded that “I am not sure … it is some time ago”!

- I don’t know what you got. I’m only going by your quotes above. You didn’t pass ANY exams. “Never completed any courses and has no qualifications in Homeopathy.” Those aren’t my words.

- LOL qualification for their cat? You didn’t even get a psuedo qualification and on top of that you practiced Homeopathy for 20 years eremember. With no qualifications. You are a fumbling and bumbling Proffessor of Cam? LOL. In fact I think I’ll make my cat a proffessor of Cam. Why not? He’ll be as qualified as you.

Often, these foaming (and in their apoplectic fury badly-spelling) defenders of homeopathy state or imply that I lied about all this. Yet, it is they who are lying, if they say so. I never claimed that I got any qualifications in homeopathy; I was trained in homeopathy by doctors of considerable standing in their field just like I was trained in many other clinical skills (what is more, I published a memoir where all this is explained in full detail).

In my bewilderment, I sometimes ask my accusers why they think I should have got a qualification in homeopathy. Sadly, so far, I have not received a logical answer (most of the time not even an illogical one).

So, today I ask the question again: WHY SHOULD I HAVE NEEDED ANY QUALIFICATION IN HOMEOPATHY?

My answers are here:

- I consider such qualifications as laughable. A proper qualification in nonsense is just nonsense!

- For practising homeopathy (which I did for a while), I did not need such qualifications; as a licensed physician, I was at liberty to use the treatments I felt to be adequate.

- For researching homeopathy (which I did too and published ~120 Medline-listed papers as a result of it), I do not need them either. Anyone can research homeopathy, and some of the most celebrated heroes of homeopathy research (e. g. Klaus Linde and Robert Mathie) do also have no such qualifications.

I am therefore truly puzzled and write this post to give everyone the chance to name the reasons why they feel I needed qualifications in homeopathy.

Please do tell me!

In one of his many comments, our friend Iqbal just linked to an article that unquestionably is interesting. Here is its abstract (the link also provides the full paper):

Objective: The objective was to assess the usefulness of homoeopathic genus epidemicus (Bryonia alba 30C) for the prevention of chikungunya during its epidemic outbreak in the state of Kerala, India.

Materials and Methods: A cluster- randomised, double- blind, placebo -controlled trial was conducted in Kerala for prevention of chikungunya during the epidemic outbreak in August-September 2007 in three panchayats of two districts. Bryonia alba 30C/placebo was randomly administered to 167 clusters (Bryonia alba 30C = 84 clusters; placebo = 83 clusters) out of which data of 158 clusters was analyzed (Bryonia alba 30C = 82 clusters; placebo = 76 clusters) . Healthy participants (absence of fever and arthralgia) were eligible for the study (Bryonia alba 30 C n = 19750; placebo n = 18479). Weekly follow-up was done for 35 days. Infection rate in the study groups was analysed and compared by use of cluster analysis.

Results: The findings showed that 2525 out of 19750 persons of Bryonia alba 30 C group suffered from chikungunya, compared to 2919 out of 18479 in placebo group. Cluster analysis showed significant difference between the two groups [rate ratio = 0.76 (95% CI 0.14 – 5.57), P value = 0.03]. The result reflects a 19.76% relative risk reduction by Bryonia alba 30C as compared to placebo.

Conclusion: Bryonia alba 30C as genus epidemicus was better than placebo in decreasing the incidence of chikungunya in Kerala. The efficacy of genus epidemicus needs to be replicated in different epidemic settings.

________________________________________________________________________________

I have often said the notion that homeopathy might prevent epidemics is purely based on observational data. Here I stand corrected. This is an RCT! What is more, it suggests that homeopathy might be effective. As this is an important claim, let me quickly post just 10 comments on this study. I will try to make this short (I only looked at it briefly), hoping that others complete my criticism where I missed important issues:

- The paper was published in THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN HOMEOPATHY. This is not a publication that could be called a top journal. If this study really shows something as revolutionarily new as its conclusions imply, one must wonder why it was published in an obscure and inaccessible journal.

- Several of its authors are homeopaths who unquestionably have an axe to grind, yet they do not declare any conflicts of interest.

- The abstract states that the trial was aimed at assessing the usefulness of Bryonia C30, while the paper itself states that it assessed its efficacy. The two are not the same, I think.

- The trial was conducted in 2007 and published only 7 years later; why the delay?

- The criteria for the main outcome measure were less than clear and had plenty of room for interpretation (“Any participant who suffered from fever and arthralgia (characteristic symptoms of chikungunya) during the follow-up period was considered as a case of chikungunya”).

- I fail to follow the logic of the sample size calculation provided by the authors and therefore believe that the trial was woefully underpowered.

- As a cluster RCT, its unit of assessment is the cluster. Yet the significant results seem to have been obtained by using single patients as the unit of assessment (“At the end of follow-ups it was observed that 12.78% (2525 out of 19750) healthy individuals, administered with Bryonia alba 30 C, were presented diagnosed as probable case of chikungunya, whereas it was 15.79% (2919 out of 18749) in the placebo group”).

- The p-value was set at 0.05. As we have often explained, this is far too low considering that the verum was a C30 dilution with zero prior probability.

- Nine clusters were not included in the analysis because of ‘non-compliance’. I doubt whether this was the correct way of dealing with this issue and think that an intention to treat analysis would have been better.

- This RCT was published 4 years ago. If true, its findings are nothing short of a sensation. Therefore, one would have expected that, by now, we would see several independent replications. The fact that this is not the case might mean that such RCTs were done but failed to confirm the findings above.

As I said, I would welcome others to have a look and tell us what they think about this potentially important study.

Kinesiology tape KT is fashionable, it seems. Gullible consumers proudly wear it as decorative ornaments to attract attention and show how very cool they are.

Am I too cynical?

Perhaps.

But does KT really do anything more?

A new trial might tell us.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether adding kinesiology tape (KT) to spinal manipulation (SM) can provide any extra effect in athletes with chronic non-specific low back pain (CNLBP).

Forty-two athletes (21males, 21females) with CNLBP were randomized into two groups of SM (n = 21) and SM plus KT (n = 21). Pain intensity, functional disability level and trunk flexor-extensor muscles endurance were assessed by Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Oswestry pain and disability index (ODI), McQuade test, and unsupported trunk holding test, respectively. The tests were done before and immediately, one day, one week, and one month after the interventions and compared between the two groups.

After treatments, pain intensity and disability level decreased and endurance of trunk flexor-extensor muscles increased significantly in both groups. Repeated measures analysis, however, showed that there was no significant difference between the groups in any of the evaluations.

The authors, physiotherapists from Iran, concluded that the findings of the present study showed that adding KT to SM does not appear to have a significant extra effect on pain, disability and muscle endurance in athletes with CNLBP. However, more studies are needed to examine the therapeutic effects of KT in treating these patients.

Regular readers of my blog will be able to predict what I have to say about this study design: A+B versus B is not a meaningful test of anything. I used to claim that it cannot possibly produce a negative result – and yet, here it seems to have done exactly that!

How come?

The way I see it, there are two possibilities to explain this:

- the KT has a mildly negative effect on CNLBP; thus the expected positive placebo-effect was neutralised to result in a null-effect overall;

- the study was under-powered such that the true inter-group difference could not manifest itself.

I think the second possibility is more likely, but it does really not matter at all. Because the only lesson we can learn from this trial is this: inadequate study designs will hardly ever generate anything worthwhile.

And this is, I think, a lesson that would be valuable for many researchers.

_______________________________________________________________________

Reference

Comparing spinal manipulation with and without Kinesio Taping® in the treatment of chronic low back pain.

I have often cautioned my readers about the ‘evidence’ supporting acupuncture (and other alternative therapies). Rightly so, I think. Here is yet another warning.

This systematic review assessed the clinical effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD). Nine trials involving 653 women were selected. A meta-analysis demonstrated that the acupuncture group had a significantly greater overall effective rate compared with the control group. Moreover, acupuncture significantly increased oestradiol levels compared with the control group. Regarding the HAMD and EPDS scores, no difference was found between the two groups. The Chinese authors concluded that acupuncture appears to be effective for postpartum depression with respect to certain outcomes. However, the evidence thus far is inconclusive. Further high-quality RCTs following standardised guidelines with a low risk of bias are needed to confirm the effectiveness of acupuncture for postpartum depression.

What a conclusion!

What a review!

What a journal!

What evidence!

Let’s start with the conclusion: if the authors feel that the evidence is ‘inconclusive’, why do they state that ‘acupuncture appears to be effective for postpartum depression‘. To me this does simply not make sense!

Such oddities are abundant in the review. The abstract does not mention the fact that all trials were from China (published in Chinese which means that people who cannot read Chinese are unable to check any of the reported findings), and their majority was of very poor quality – two good reasons to discard the lot without further ado and conclude that there is no reliable evidence at all.

The authors also tell us very little about the treatments used in the control groups. In the paper, they state that “the control group needed to have received a placebo or any type of herb, drug and psychological intervention”. But was acupuncture better than all or any of these treatments? I could not find sufficient data in the paper to answer this question.

Moreover, only three trials seem to have bothered to mention adverse effects. Thus the majority of the studies were in breach of research ethics. No mention is made of this in the discussion.

In the paper, the authors re-state that “this meta-analysis showed that the acupuncture group had a significantly greater overall effective rate compared with the control group. Moreover, acupuncture significantly increased oestradiol levels compared with the control group.” This is, I think, highly misleading (see above).

Finally, let’s have a quick look at the journal ‘Acupuncture in Medicine’ (AiM). Even though it is published by the BMJ group (the reason for this phenomenon can be found here: “AiM is owned by the British Medical Acupuncture Society and published by BMJ”; this means that all BMAS-members automatically receive the journal which thus is a resounding commercial success), it is little more than a cult-newsletter. The editorial board is full of acupuncture enthusiasts, and the journal hardly ever publishes anything that is remotely critical of the wonderous myths of acupuncture.

My conclusion considering all this is as follows: we ought to be very careful before accepting any ‘evidence’ that is currently being published about the benefits of acupuncture, even if it superficially looks ok. More often than not, it turns out to be profoundly misleading, utterly useless and potentially harmful pseudo-evidence.

Reference

Acupunct Med. 2018 Jun 15. pii: acupmed-2017-011530. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2017-011530. [Epub ahead of print]

Effectiveness of acupuncture in postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Li S, Zhong W, Peng W, Jiang G.

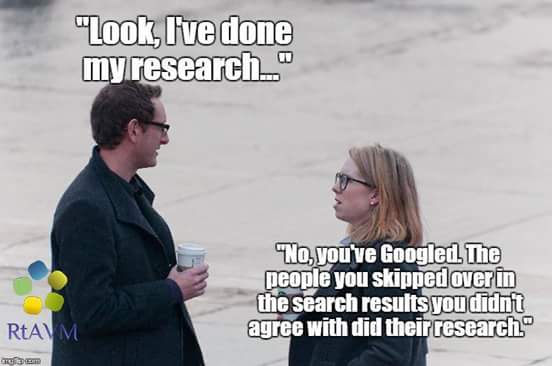

How often do we hear this sentence: “I know, because I have done my research!” I don’t doubt that most people who make this claim believe it to be true.

But is it?

What many mean by saying, “I know, because I have done my research”, is that they went on the internet and looked at a few websites. Others might have been more thorough and read books and perhaps even some original papers. But does that justify their claim, “I know, because I have done my research”?

The thing is, there is research and there is research.

The dictionary defines research as “The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions.” This definition is helpful because it mentions several issues which, I believe, are important.

Research should be:

- systematic,

- an investigation,

- establish facts,

- reach new conclusions.

To me, this indicates that none of the following can be truly called research:

- looking at a few randomly chosen papers,

- merely reading material published by others,

- uncritically adopting the views of others,

- repeating the conclusions of others.

Obviously, I am being very harsh and uncompromising here. Not many people could, according to these principles, truthfully claim to have done research in alternative medicine. Most people in this realm do not fulfil any of those criteria.

As I said, there is research and research – research that meets the above criteria, and the type of research most people mean when they claim: “I know, because I have done my research.”

Personally, I don’t mind that the term ‘research’ is used in more than one way:

- there is research meeting the criteria of the strict definition

- and there is a common usage of the word.

But what I do mind, however, is when the real research is claimed to be as relevant and reliable as the common usage of the term. This would be a classical false equivalence, akin to putting experts on a par with pseudo-experts, to believing that facts are no different from fantasy, or to assume that truth is akin to post-truth.

Sadly, in the realm of alternative medicine (and alarmingly, in other areas as well), this is exactly what has happened since quite some time. No doubt, this might be one reason why many consumers are so confused and often make wrong, sometimes dangerous therapeutic decisions. And this is why I think it is important to point out the difference between research and research.