pain

This study used a US nationally representative 11-year sample of office-based visits to physicians from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), to examine a comprehensive list of factors believed to be associated with visits where complementary health approaches were recommended or provided.

NAMCS is a national health care survey designed to collect data on the provision and use of ambulatory medical care services provided by office-based physicians in the United States. Patient medical records were abstracted from a random sample of office-based physician visits. The investigators examined several visit characteristics, including patient demographics, physician specialty, documented health conditions, and reasons for a health visit. They ran chi-square analyses to test bivariate associations between visit factors and whether complementary health approaches were recommended or provided to guide the development of logistic regression models.

Of the 550,114 office visits abstracted, 4.43% contained a report that complementary health approaches were ordered, supplied, administered, or continued. Among complementary health visits, 87% of patient charts mentioned nonvitamin nonmineral dietary supplements. The prevalence of complementary health visits significantly increased from 2% in 2005 to almost 8% in 2015. Returning patient status, survey year, physician specialty and degree, menopause, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal diagnoses were significantly associated with complementary health visits, as was seeking preventative care or care for a chronic problem.

The authors concluded that these data confirm the growing popularity of complementary health approaches in the United States, provide a baseline for further studies, and inform subsequent investigations of integrative health care.

The authors used the same dataset for a 2nd paper which examined the reasons why office-based physicians do or do not recommend four selected complementary health approaches to their patients in the context of the Andersen Behavioral Model. Descriptive estimates were employed of physician-level data from the 2012 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) Physician Induction Interview, a nationally representative survey of office-based physicians (N = 5622, weighted response rate = 59.7%). The endpoints were the reasons for the recommendation or lack thereof to patients for:

- herbs,

- other non-vitamin supplements,

- chiropractic/osteopathic manipulation,

- acupuncture,

- mind-body therapies (including meditation, guided imagery, and progressive relaxation).

Differences by physician sex and medical specialty were described.

For each of the four complementary health approaches, more than half of the physicians who made recommendations indicated that they were influenced by scientific evidence in peer-reviewed journals (ranging from 52.0% for chiropractic/osteopathic manipulation [95% confidence interval, CI = 47.6-56.3] to 71.3% for herbs and other non-vitamin supplements [95% CI = 66.9-75.4]). More than 60% of all physicians recommended each of the four complementary health approaches because of patient requests. A higher percentage of female physicians reported evidence in peer-reviewed journals as a rationale for recommending herbs and non-vitamin supplements or chiropractic/osteopathic manipulation when compared with male physicians (herbs and non-vitamin supplements: 78.8% [95% CI = 72.4-84.3] vs. 66.6% [95% CI = 60.8-72.2]; chiropractic/osteopathic manipulation: 62.3% [95% CI = 54.7-69.4] vs. 47.5% [95% CI = 42.3-52.7]).

For each of the four complementary health approaches, a lack of perceived benefit was the most frequently reported reason by both sexes for not recommending. Lack of information sources was reported more often by female versus male physicians as a reason to not recommend herbs and non-vitamin supplements (31.4% [95% CI = 26.8-36.3] vs. 23.4% [95% CI = 21.0-25.9]).

The authors concluded that there are limited nationally representative data on the reasons as to why office-based physicians decide to recommend complementary health approaches to patients. Developing a more nuanced understanding of influencing factors in physicians’ decision making regarding complementary health approaches may better inform researchers and educators, and aid physicians in making evidence-based recommendations for patients.

I am not sure what these papers really offer in terms of information that is not obvious or that makes a meaningful contribution to progress. It almost seems that, because the data of such surveys are available, such analyses get done and published. The far better reason for doing research is, of course, the desire to answer a burning and relevant research question.

A problem then arises when researchers, who perceive the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) as a fundamentally good thing, write a paper that smells more of SCAM promotion than meaningful science. Having said that, I find it encouraging to read in the two papers that

- the prevalence of SCAM remains quite low,

- more than 60% of all physicians recommended SCAM not because they were convinced of its value but because of patient requests,

- the lack of perceived benefit was the most frequently reported reason for not recommending it.

Osteopathic visceral manipulation (VM) is a bizarre so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that has been featured on this blog with some regularity, e.g.:

- Osteopathic visceral manipulation: a new study fails to convince anyone

- Visceral manipulation…you couldn’t make it up

- Intravaginal manipulations by (German) osteopaths: a new low point for clinical research into alternative medicine?

- Visceral osteopathy is implausible and does not work … SO, LET’S FORGET ABOUT IT ONCE AND FOR ALL

Rigorous trials fail to show that it works for anything. So, the obvious solution to this dilemma is to conduct dodgy trials!

This study tested the effects of VM on dysmenorrhea, irregular, delayed, and/or absent menses, and premenstrual symptoms in PCOS patients.

Thirty Egyptian women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), with menstruation-related complaints and free from systematic diseases and/or adrenal gland abnormalities, participated in a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. They were recruited from the women’s health outpatient clinic in the faculty of physical therapy at Cairo University, with an age of 20-34 years, and a body mass index (BMI) ≥25, <30 kg/m2. Patients were randomly allocated into two equal groups (15 patients); the control group received a low-calorie diet for 3 months, and the study group that received the same hypocaloric diet added to VM to the pelvic organs and their related structures for eight sessions over 3 months. Evaluations for body weight, BMI, and menstrual problems were done by weight-height scale, and menstruation-domain of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (PCOSQ), respectively, at baseline and after 3 months from interventions. Data were described as mean, standard deviation, range, and percentage whenever applicable.

Of 60 Egyptian women with PCOS, 30 patients were included, with baseline mean age, weight, BMI, and a menstruation domain score of 27.5 ± 2.2 years, 77.7 ± 4.3 kg, 28.6 ± 0.7 kg/m2, and 3.4 ± 1.0, respectively, for the control group, and 26.2 ± 4.7 years, 74.6 ± 3.5 kg, 28.2 ± 1.1 kg/m2, and 2.9 ± 1.0, respectively, for the study group. Out of the 15 patients in the study group, uterine adhesions were found in 14 patients (93.3%), followed by restricted uterine mobility in 13 patients (86.7%), restricted ovarian/broad ligament mobility (9, 60%), and restricted motility (6, 40%). At baseline, there was no significant difference (p>0.05) in any of the demographics (age, height), or dependent variables (weight, BMI, menstruation domain score) among both groups. Post-study, there was a statistically significant reduction (p=0.000) in weight, and BMI mean values for the diet group (71.2 ± 4.2 kg, and 26.4 ± 0.8 kg/m2, respectively) and the diet + VM group (69.2 ± 3.7 kg; 26.1 ± 0.9 kg/m2, respectively). For the improvement in the menstrual complaints, a significant increase (p<0.05) in the menstruation domain mean score was shown in the diet group (3.9 ± 1.0), and the diet + VM group (4.6 ± 0.5). On comparing both groups post-study, there was a statistically significant improvement (p=0.024) in the severity of menstruation-related problems in favor of the diet + VM group.

The authors concluded that VM yielded greater improvement in menstrual pain, irregularities, and premenstrual symptoms in PCOS patients when added to caloric restriction than utilizing the low-calorie diet alone in treating that condition.

WHERE TO START?

- Tiny sample size.

- A trail design (A+B vs B) which will inevitably generate a positive result.

- Questionable ethics.

VM is a relatively invasive and potentially embarrassing intervention for any woman; I imagine that this is all the more true in Egypt. In such circumstances, it is mandatory to ask whether a planned study is ethically justifiable. I would answer this question related to an implausible treatment like VM with a straight NO!

I realize that there may be people who disagree with me. But even those guys should accept that, at the very minimum, such a study must be designed such that it leads to a clear answer – is VM effective or not? The present trial merely suggests that the placebo effect associated with VM is powerful (which is hardly surprising for a therapy like VM).

Spondyloptosis is a grade V spondylolisthesis – a vertebra having slipped so far with respect to the vertebra below that the two endplates are no longer congruent. It is usually seen in the lower lumbar spine but rarely can be seen in other spinal regions as well. Spondyloptosis is most commonly caused by trauma. It is defined as the dislocation of the spinal column in which the spondyloptotic vertebral body is either anteriorly or posteriorly displaced (>100%) on the adjacent vertebral body. Only a few cases of cervical spondyloptosis have been reported. The cervical cord injury in most patients is complete and irreversible. In most cases of cervical spondyloptosis, regardless of whether there is a neurologic deficit or not, reduction and stabilization of the fracture-dislocation is the management of choice

The case of a 16-year-old boy was reported who had been diagnosed with spondyloptosis of the cervical spine at the C5-6 level with a neurologic deficit following cervical manipulation by a traditional massage therapist. He could not move his upper and lower extremities, but the sensory and autonomic function was spared. The pre-operative American Spinal Cord Injury Association (ASIA) Score was B with SF-36 at 25%, and Karnofsky’s score was 40%. The patient was disabled and required special care and assistance.

The surgeons performed anterior decompression, cervical corpectomy at the level of C6 and lower part of C5, deformity correction, cage insertion, bone grafting, and stabilization with an anterior cervical plate. The patient’s objective functional score had increased after six months of follow-up and assessed objectively with the ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) E or (excellent), an SF-36 score of 94%, and a Karnofsky score of 90%. The patient could carry on his regular activity with only minor signs or symptoms of the condition.

The authors concluded that this case report highlights severe complications following cervical manipulation, a summary of the clinical presentation, surgical treatment choices, and a review of the relevant literature. In addition, the sequential improvement of the patient’s functional outcome after surgical correction will be discussed.

This is a dramatic and interesting case. Looking at the above pre-operative CT scan, I am not sure how the patient could have survived. I am also not aware of previous similar cases. This does, however, not mean they don’t exist. Perhaps most affected patients simply died without being diagnosed. So, do we need to add spondyloptosis to the (hopefully) rare but severe complications of spinal manipulation?

I know, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is not really a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) but it is used by many SCAM practitioners and pain patients. It is, therefore, worth knowing whether it works.

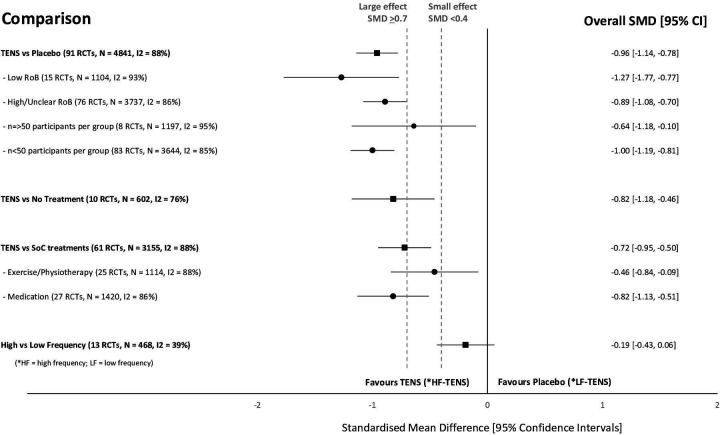

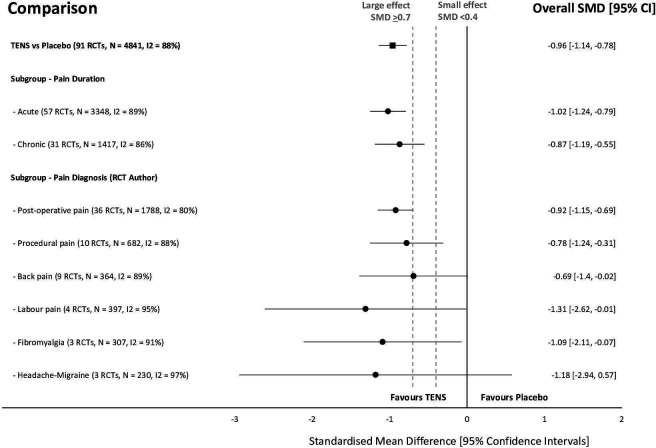

This systematic review investigated the efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for the relief of pain in adults. All randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were considered which compared strong non-painful TENS at or close to the site of pain versus placebo or other treatments in adults with pain, irrespective of diagnosis.

Reviewers independently screened, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias (RoB, Cochrane tool) and certainty of evidence (Grading and Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation). The outcome measures were the mean pain intensity and the proportions of participants achieving reductions of pain intensity (≥30% or >50%) during or immediately after TENS. Random effect models were used to calculate standardized mean differences (SMD) and risk ratios. Subgroup analyses were related to trial methodology and characteristics of pain.

The review included 381 RCTs (24 532 participants). Pain intensity was lower during or immediately after TENS compared with placebo (91 RCTs, 92 samples, n=4841, SMD=-0·96 (95% CI -1·14 to -0·78), moderate-certainty evidence). Methodological (eg, RoB, sample size) and pain characteristics (eg, acute vs chronic, diagnosis) did not modify the effect. Pain intensity was lower during or immediately after TENS compared with pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments used as part of standard of care (61 RCTs, 61 samples, n=3155, SMD = -0·72 (95% CI -0·95 to -0·50], low-certainty evidence). Levels of evidence were downgraded because of small-sized trials contributing to imprecision in magnitude estimates. Data were limited for other outcomes including adverse events which were poorly reported, generally mild, and not different from comparators.

The authors concluded that there was moderate-certainty evidence that pain intensity is lower during or immediately after TENS compared with placebo and without serious adverse events.

This is an impressive review, not least because of its rigorous methodology and the large number of included trials. Its results are clear and convincing. In the words of the authors: “TENS should be considered in a similar manner to rubbing, cooling or warming the skin to provide symptomatic relief of pain via neuromodulation. One advantage of TENS is that users can adjust electrical characteristics to produce a wide variety of TENS sensations such as pulsate and paraesthesiae to combat the dynamic nature of pain. Consequently, patients need to learn how to use a systematic process of trial and error to select electrode positions and electrical characteristics to optimise benefits and minimise problems on a moment to moment basis.”

Given the high prevalence of burdensome symptoms in palliative care (PC) and the increasing use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) therapies, research is needed to determine how often and what types of SCAM therapies providers recommend to manage symptoms in PC.

This survey documented recommendation rates of SCAM for target symptoms and assessed if, SCAM use varies by provider characteristics. The investigators conducted US nationwide surveys of MDs, DOs, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners working in PC.

Participants (N = 404) were mostly female (71.3%), MDs/DOs (74.9%), and cared for adults (90.4%). Providers recommended SCAM an average of 6.8 times per month (95% CI: 6.0-7.6) and used an average of 5.1 (95% CI: 4.9-5.3) out of 10 listed SCAM modalities. Respondents recommended mostly:

- mind-body medicines (e.g., meditation, biofeedback),

- massage,

- acupuncture/acupressure.

The most targeted symptoms included:

- pain,

- anxiety,

- mood disturbances,

- distress.

Recommendation frequencies for specific modality-for-symptom combinations ranged from little use (e.g. aromatherapy for constipation) to occasional use (e.g. mind-body interventions for psychiatric symptoms). Finally, recommendation rates increased as a function of pediatric practice, noninpatient practice setting, provider age, and proportion of effort spent delivering palliative care.

The authors concluded that to the best of our knowledge, this is the first national survey to characterize PC providers’ SCAM recommendation behaviors and assess specific therapies and common target symptoms. Providers recommended a broad range of SCAM but do so less frequently than patients report using SCAM. These findings should be of interest to any provider caring for patients with serious illness.

Initially, one might feel encouraged by these data. Mind-body therapies are indeed supported by reasonably sound evidence for the symptoms listed. The evidence is, however, not convincing for many other forms of SCAM, in particular massage or acupuncture/acupressure. So encouragement is quickly followed by disappointment.

Some people might say that in PC one must not insist on good evidence: if the patient wants it, why not? But the point is that there are several forms of SCAMs that are backed by good evidence for use in PC. So, why not follow the evidence and use those? It seems to me that it is not in the patients’ best interest to disregard the evidence in medicine – and this, of course, includes PC.

Acupuncture for animals has a long history in China. In the West, it was introduced in the 1970s when acupuncture became popular for humans. A recent article sums up our current knowledge on the subject. Here is an excerpt:

Acupuncture is used mainly for functional problems such as those involving noninfectious inflammation, paralysis, or pain. For small animals, acupuncture has been used for treating arthritis, hip dysplasia, lick granuloma, feline asthma, diarrhea, and certain reproductive problems. For larger animals, acupuncture has been used for treating downer cow syndrome, facial nerve paralysis, allergic dermatitis, respiratory problems, nonsurgical colic, and certain reproductive disorders.Acupuncture has also been used on competitive animals. There are veterinarians who use acupuncture along with herbs to treat muscle injuries in dogs and cats. Veterinarians charge around $85 for each acupuncture session.[8]Veterinary acupuncture has also recently been used on more exotic animals, such as chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)[9] and an alligator with scoliosis,[10] though this is still quite rare.

To put it in a nutshell: acupuncture for animals is not evidence-based.

How can I be so sure?

Because ref 1 in the text above refers to our paper. Here is its abstract:

Acupuncture is a popular complementary treatment option in human medicine. Increasingly, owners also seek acupuncture for their animals. The aim of the systematic review reported here was to summarize and assess the clinical evidence for or against the effectiveness of acupuncture in veterinary medicine. Systematic searches were conducted on Medline, Embase, Amed, Cinahl, Japana Centra Revuo Medicina and Chikusan Bunken Kensaku. Hand-searches included conference proceedings, bibliographies, and contact with experts and veterinary acupuncture associations. There were no restrictions regarding the language of publication. All controlled clinical trials testing acupuncture in any condition of domestic animals were included. Studies using laboratory animals were excluded. Titles and abstracts of identified articles were read, and hard copies were obtained. Inclusion and exclusion of studies, data extraction, and validation were performed independently by two reviewers. Methodologic quality was evaluated by means of the Jadad score. Fourteen randomized controlled trials and 17 nonrandomized controlled trials met our criteria and were, therefore, included. The methodologic quality of these trials was variable but, on average, was low. For cutaneous pain and diarrhea, encouraging evidence exists that warrants further investigation in rigorous trials. Single studies reported some positive intergroup differences for spinal cord injury, Cushing’s syndrome, lung function, hepatitis, and rumen acidosis. These trials require independent replication. On the basis of the findings of this systematic review, there is no compelling evidence to recommend or reject acupuncture for any condition in domestic animals. Some encouraging data do exist that warrant further investigation in independent rigorous trials.

This evidence is in sharp contrast to the misinformation published by the ‘IVAS’ (International Veterinary Acupuncture Society). Under the heading “For Which Conditions is Acupuncture Indicated?“, they propagate the following myth:

Acupuncture is indicated for functional problems such as those that involve paralysis, noninfectious inflammation (such as allergies), and pain. For small animals, the following are some of the general conditions which may be treated with acupuncture:

- Musculoskeletal problems, such as arthritis, intervertebral disk disease, or traumatic nerve injury

- Respiratory problems, such as feline asthma

- Skin problems such as lick granulomas and allergic dermatitis

- Gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea

- Selected reproductive problems

For large animals, acupuncture is again commonly used for functional problems. Some of the general conditions where it might be applied are the following:

- Musculoskeletal problems such as sore backs or downer cow syndrome

- Neurological problems such as facial paralysis

- Skin problems such as allergic dermatitis

- Respiratory problems such as heaves and “bleeders”

- Gastrointestinal problems such as nonsurgical colic

- Selected reproductive problems

In addition, regular acupuncture treatment can treat minor sports injuries as they occur and help to keep muscles and tendons resistant to injury. World-class professional and amateur athletes often use acupuncture as a routine part of their training. If your animals are involved in any athletic endeavor, such as racing, jumping, or showing, acupuncture can help them keep in top physical condition.

And what is the conclusion?

Perhaps this?

Never trust the promotional rubbish produced by SCAM organizations.

There is a lack of data describing the state of naturopathic or complementary veterinary medicine in Germany. This survey maps the currently used treatment modalities, indications, existing qualifications, and information pathways. It records the advantages and disadvantages of these medicines as experienced by veterinarians. Demographic influences are investigated to describe the distributional impacts of using veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine.

A standardized questionnaire was used for the cross-sectional survey. It was distributed throughout Germany in a written and digital format from September 2016 to January 2018. Because of the open nature of data collection, the return rate of questionnaires could not be calculated. To establish a feasible timeframe, active data collection stopped when the previously calculated limit of 1061 questionnaires was reached.

With the included incoming questionnaires of that day, a total of 1087 questionnaires were collected. Completely blank questionnaires and those where participants did not meet the inclusion criteria were not included, leaving 870 out of 1087 questionnaires to be evaluated. A literature review and the first test run of the questionnaire identified the following treatment modalities:

- homeopathy,

- phytotherapy,

- traditional Chinese medicine (TCM),

- biophysical treatments,

- manual treatments,

- Bach Flower Remedies,

- neural therapy,

- homotoxicology,

- organotherapy,

- hirudotherapy.

These were included in the questionnaire. Categorical items were processed using descriptive statistics in absolute and relative numbers based on the population of completed answers provided for each item. Multiple choices were possible.

Overall 85.4% of all the questionnaire participants used naturopathy and complementary medicine. The treatments most commonly used were:

- complex homoeopathy (70.4%, n = 478),

- phytotherapy (60.2%, n = 409),

- classic homoeopathy (44.3%, n = 301),

- biophysical treatments (40.1%, n = 272).

The most common indications were:

- orthopedic (n = 1798),

- geriatric (n = 1428),

- metabolic diseases (n = 1124).

Over the last five years, owner demand for naturopathy and complementary treatments was rated as growing by 57.9% of respondents (n = 457 of total 789). Veterinarians most commonly used scientific journals and publications as sources for information about naturopathic and complementary contents (60.8%, n = 479 of total 788). These were followed by advanced training acknowledged by the ATF (Academy for Veterinary Continuing Education, an organisation that certifies independent veterinary continuing education in Germany) (48.6%, n = 383). The current information about naturopathy and complementary medicine was rated as adequate or nearly adequate by many (39.5%, n = 308) of the respondents.

The most commonly named advantages in using veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine were:

- expansion of treatment modalities (73.5%, n = 566 of total 770),

- customer satisfaction (70.8%, n = 545),

- lower side effects (63.2%, n = 487).

The ambiguity and unclear evidence of the mode of action and effectiveness (62.1%, n = 483) and high expectations of owners (50.5%, n = 393) were the disadvantages mentioned most frequently. Classic homoeopathy, in particular, has been named in this context (78.4%, n = 333 of total 425). Age, gender, and type of employment showed a statistically significant impact on the use of naturopathy and complementary medicine by veterinarians (p < 0.001). The university of final graduation showed a weaker but still statistically significant impact (p = 0.027). Users of veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine tended to be older, female, self-employed and a higher percentage of them completed their studies at the University of Berlin. The working environment (rural or urban space) showed no statistical impact on the veterinary naturopathy or complementary medicine profession.

The authors concluded that this is the first study to provide German data on the actual use of naturopathy and complementary medicine in small animal science. Despite a potential bias due to voluntary participation, it shows a large number of applications for various indications. Homoeopathy was mentioned most frequently as the treatment option with the most potential disadvantages. However, it is also the most frequently used treatment option in this study. The presented study, despite its restrictions, supports the need for a discussion about evidence, official regulations, and the need for acknowledged qualifications because of the widespread application of veterinary naturopathy and complementary medicine. More data regarding the effectiveness and the mode of action is needed to enable veterinarians to provide evidence-based advice to pet owners.

I can only hope that the findings are seriously biased and not a true reflection of the real situation. The methodology used for recruiting participants (it is fair to assume that those vets who had no interest in SCAM did not bother to respond) strongly indicates that this might be the case. If, however, the findings were true, one would have to conclude that, for German vets, evidence-based healthcare is still an alien concept. The evidence that the preferred SCAMs are effective for the listed conditions is very weak or even negative. If the findings were true, one would need to wonder how much of veterinary SCAM use amounts to animal abuse.

The objective of this study was to compare chronic low back pain patients’ perspectives on the use of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) compared to prescription drug therapy (PDT) with regard to health-related quality of life (HRQoL), patient beliefs, and satisfaction with treatment.

Four cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries were assembled according to previous treatment received as evidenced in claims data:

- The SMT group began long-term management with SMT but no prescribed drugs.

- The PDT group began long-term management with prescription drug therapy but no spinal manipulation.

- This group employed SMT for chronic back pain, followed by initiation of long-term management with PDT in the same year.

- This group used PDT for chronic back pain followed by initiation of long-term management with SMT in the same year.

A total of 1986 surveys were sent out and 195 participants completed the survey. The respondents were predominantly female and white, with a mean age of approx. 77-78 years. Outcome measures used were a 0-to-10 numeric rating scale to measure satisfaction, the Low Back Pain Treatment Beliefs Questionnaire to measure patient beliefs, and the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey to measure HRQoL.

Recipients of SMT were more likely to be very satisfied with their care (84%) than recipients of PDT (50%; P = .002). The SMT cohort self-reported significantly higher HRQoL compared to the PDT cohort; mean differences in physical and mental health scores on the 12-item Short Form Health Survey were 12.85 and 9.92, respectively. The SMT cohort had a lower degree of concern regarding chiropractic care for their back pain compared to the PDT cohort’s reported concern about PDT (P = .03).

The authors concluded that among older Medicare beneficiaries with chronic low back pain, long-term recipients of SMT had higher self-reported rates of HRQoL and greater satisfaction with their modality of care than long-term recipients of PDT. Participants who had longer-term management of care were more likely to have positive attitudes and beliefs toward the mode of care they received.

The main issue here is that the ‘study’ was a mere survey which by definition cannot establish cause and effect. The groups were different in many respects which rendered them not comparable. For instance, participants who received SMT had higher self-reported physical and mental health on average than those who received PDT. Differences also existed between the SMT and the PDT groups for agreement with the notion that “spinal manipulation for LBP makes a lot of sense”; 96% of the SMT group and 35% of the PDT group agreed with it. Compare this with another statement, “taking /having prescription drug therapy for LBP makes a lot of sense” and we find that only 13% of the SMT cohort agreed with, 95% of the PDT cohort agreed. Thus, a powerful bias exists toward the type of therapy that each person had chosen. Another determinant of the outcome is the fact that SMT means hands-on treatments with time, compassion, and empathy given to the patient, whereas PDT does not necessarily include such features. Add to these limitations the dismal response rate, recall bias, and numerous potential confounders and you have a survey that is hardly worth the paper it is printed on. In fact, it is little more than a marketing exercise for chiropractic.

In summary, the findings of this survey are influenced by a whole range of known and unknown factors other than the SMT. The authors are clever to avoid causal inferences in their conclusions. I doubt, however, that many chiropractors reading the paper think critically enough to do the same.

This study describes the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) among older adults who report being hampered in daily activities due to musculoskeletal pain. The characteristics of older adults with debilitating musculoskeletal pain who report SCAM use is also examined. For this purpose, the cross-sectional European Social Survey Round 7 from 21 countries was employed. It examined participants aged 55 years and older, who reported musculoskeletal pain that hampered daily activities in the past 12 months.

Of the 4950 older adult participants, the majority (63.5%) were from the West of Europe, reported secondary education or less (78.2%), and reported at least one other health-related problem (74.6%). In total, 1657 (33.5%) reported using at least one SCAM treatment in the previous year.

The most commonly used SCAMs were:

- manual body-based therapies (MBBTs) including massage therapy (17.9%),

- osteopathy (7.0%),

- homeopathy (6.5%)

- herbal treatments (5.3%).

SCAM use was positively associated with:

- younger age,

- physiotherapy use,

- female gender,

- higher levels of education,

- being in employment,

- living in West Europe,

- multiple health problems.

(Many years ago, I have summarized the most consistent determinants of SCAM use with the acronym ‘FAME‘ [female, affluent, middle-aged, educated])

The authors concluded that a third of older Europeans with musculoskeletal pain report SCAM use in the previous 12 months. Certain subgroups with higher rates of SCAM use could be identified. Clinicians should comprehensively and routinely assess SCAM use among older adults with musculoskeletal pain.

I often mutter about the plethora of SCAM surveys that report nothing meaningful. This one is better than most. Yet, much of what it shows has been demonstrated before.

I think what this survey confirms foremost is the fact that the popularity of a particular SCAM and the evidence that it is effective are two factors that are largely unrelated. In my view, this means that more, much more, needs to be done to inform the public responsibly. This would entail making it much clearer:

- which forms of SCAM are effective for which condition or symptom,

- which are not effective,

- which are dangerous,

- and which treatment (SCAM or conventional) has the best risk/benefit balance.

Such information could help prevent unnecessary suffering (the use of ineffective SCAMs must inevitably lead to fewer symptoms being optimally treated) as well as reduce the evidently huge waste of money spent on useless SCAMs.

There is hardly a form of therapy under the SCAM umbrella that is not promoted for back pain. None of them is backed by convincing evidence. This might be because back problems are mostly viewed in SCAM as mechanical by nature, and psychological elements are thus often neglected.

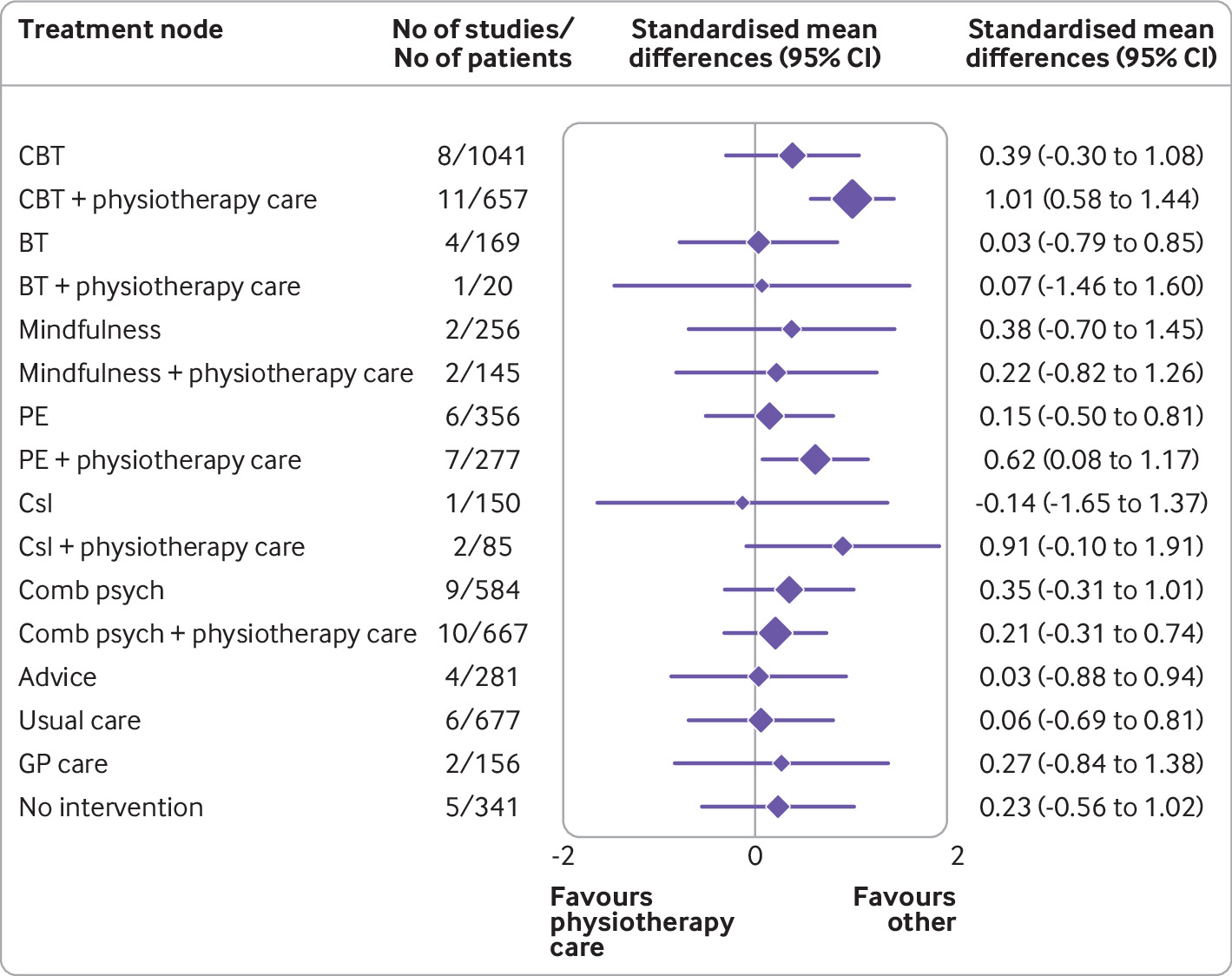

This systematic review with network meta-analysis determined the comparative effectiveness and safety of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Randomised controlled trials comparing psychological interventions with any comparison intervention in adults with chronic, non-specific low back pain were included.

A total of 97 randomised controlled trials involving 13 136 participants and 17 treatment nodes were included. Inconsistency was detected at short term and mid-term follow-up for physical function, and short term follow-up for pain intensity, and were resolved through sensitivity analyses. For physical function, cognitive behavioural therapy (standardised mean difference 1.01, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 1.44), and pain education (0.62, 0.08 to 1.17), delivered with physiotherapy care, resulted in clinically important improvements at post-intervention (moderate-quality evidence). The most sustainable effects of treatment for improving physical function were reported with pain education delivered with physiotherapy care, at least until mid-term follow-up (0.63, 0.25 to 1.00; low-quality evidence). No studies investigated the long term effectiveness of pain education delivered with physiotherapy care. For pain intensity, behavioural therapy (1.08, 0.22 to 1.94), cognitive behavioural therapy (0.92, 0.43 to 1.42), and pain education (0.91, 0.37 to 1.45), delivered with physiotherapy care, resulted in clinically important effects at post-intervention (low to moderate-quality evidence). Only behavioural therapy delivered with physiotherapy care maintained clinically important effects on reducing pain intensity until mid-term follow-up (1.01, 0.41 to 1.60; high-quality evidence).

Forest plot of network meta-analysis results for physical function at post-intervention. *Denotes significance at p<0.05. BT=behavioural therapy; CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy; Comb psych=combined psychological approaches; Csl=counselling; GP care=general practitioner care; PE=pain education; SMD=standardised mean difference. Physiotherapy care was the reference comparison group

The authors concluded that for people with chronic, non-specific low back pain, psychological interventions are most effective when delivered in conjunction with physiotherapy care (mainly structured exercise). Pain education programmes (low to moderate-quality evidence) and behavioural therapy (low to high-quality evidence) result in the most sustainable effects of treatment; however, uncertainty remains as to their long term effectiveness. Although inconsistency was detected, potential sources were identified and resolved.

The authors’ further comment that their review has identified that pain education, behavioural therapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy are the most effective psychological interventions for people with chronic, non-specific LBP post-intervention when delivered with physiotherapy care. The most sustainable effects of treatment for physical function and fear avoidance are achieved with pain education programmes, and for pain intensity, they are achieved with behavioural therapy. Although their clinical effectiveness diminishes over time, particularly in the long term (≥12 months post-intervention), evidence supports the clinical benefits of combining physiotherapy care with these specific types of psychological interventions at the onset of treatment. The small total sample size at long term follow-up (eg, for physical function, n=6986 at post-intervention v n=2469 for long term follow-up; for pain intensity, n=6963 v n=2272) has resulted in wide confidence intervals at this time point; however, the magnitude and direction of the pooled effects seemed to consistently favour the psychological interventions delivered with physiotherapy care, compared with physiotherapy care alone.

Commenting on their paper, two of the authors, Ferriera and Ho, said they would like to see the guidelines on LBP therapy updated to provide more specific recommendations, the “whole idea” is to inform patients, so they can have conversations with their GP or physiotherapist. Patients should not come to consultations with a passive attitude of just receiving whatever people tell them because unfortunately people still receive the wrong care for chronic back pain,” Ferreira says. “Clinicians prescribe anti-inflammatories or paracetamol. We need to educate patients and clinicians about options and more effective ways of managing pain.”

Is there a lesson here for patients consulting SCAM practitioners for their back pain? Perhaps it is this: it is wise to choose the therapy that has been demonstrated to be effective while having the least potential for harm! And this is not chiropractic or any other form of SCAM. It could, however, well be a combination of physiotherapeutic exercise and psychological therapy.