neck-pain

Japanese neurosurgeons reported the case of A 55-year-old man who presented with progressive pain and expanding swelling in his right neck. He had no history of trauma or infectious disease. The patient had undergone chiropractic manipulations once in a month and the last manipulation was done one day before the admission to hospital.

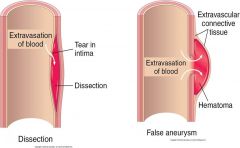

On examination by laryngeal endoscopy, a swelling was found on the posterior wall of the pharynx on the right side. The right piriform fossa was invisible. CT revealed hematoma in the posterior wall of the right oropharynx compressing the airway tract. Aneurysm-like enhanced lesion was also seen near the right common carotid artery. Ultrasound imaging revealed a fistula of approximately 1.2 mm at the posterior wall of the external carotid artery and inflow image of blood to the aneurysm of a diameter of approximately 12 mm. No dissection or stenosis of the artery was found. Jet inflow of blood into the aneurysm was confirmed by angiography. T1-weighted MR imaging revealed presence of hematoma on the posterior wall of the pharynx and the aneurysm was recognized by gadolinium-enhancement.

The neurosurgeons performed an emergency operation to remove the aneurysm while preserving the patency of the external carotid artery. The pin-hole fistula was sutured and the wall of the aneurysm was removed. Histopathological assessment of the tissue revealed a pseudoaneurysm (also called a false aneurism), a collection of blood that forms between the two outer layers of an artery.

The patient was discharged after 12 days without a neurological deficit. Progressively growing aneurysm of the external carotid artery is caused by various factors and early intervention is recommended. Although, currently, intravascular surgery is commonly indicated, direct surgery is also feasible and has advantages with regard to pathological diagnosis and complete repair of the parent artery.

The relationship between the pseudoaneurysm and the chiropractic manipulations seems unclear. The way I see it, there are the following three possibilities:

- The manipulations have causally contributed to the pseudo-aneurysm.

- They have exacerbated the condition and/or its symptoms.

- They are unrelated to the condition.

If someone is able to read the Japanese full text of this paper, please let us know what the neurosurgeons thought about this.

Osteopathy is a tricky subject:

- Osteopathic manipulations/mobilisations are advocated mainly for spinal complaints.

- Yet many osteopaths use them also for a myriad of non-spinal conditions.

- Osteopathy comprises two entirely different professions; in the US, osteopaths are very similar to medically trained doctors, and many hardly ever employ osteopathic manual techniques; outside the US, osteopaths are alternative practitioners who use mainly osteopathic techniques and believe in the obsolete gospel of their guru Andrew Taylor Still (this post relates to the latter type of osteopathy).

- The question whether osteopathic manual therapies are effective is still open – even for the indication that osteopaths treat most, spinal complaints.

- Like chiropractors, osteopaths now insist that osteopathy is not a treatment but a profession; the transparent reason for this argument is to gain more wriggle-room when faced with negative evidence regarding they hallmark treatment of osteopathic manipulation/mobilisation.

A new paper authored by osteopaths is an attempt to shed more light on the effectiveness of osteopathy. The aim of this systematic review evaluated the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints. Only randomized controlled trials conducted in high-income Western countries were considered. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts. Primary outcomes included ‘pain’ and ‘functional status’, while secondary outcomes included ‘medication use’ and ‘health status’.

Nineteen studies were included and qualitatively synthesized. Nine studies were from the US, followed by Germany with 7 studies. The majority of studies (n = 13) focused on low back pain.

In general, mixed findings related to the impact of osteopathic care on primary and secondary outcomes were observed. For the primary outcomes, a clear distinction between US and European studies was found, where the latter RCTs reported positive results more frequently. Studies were characterized by substantial methodological differences in sample sizes, number of treatments, control groups, and follow-up.

The authors concluded that “the findings of the current literature review suggested that osteopathic care may improve pain and functional status in patients suffering from spinal complaints. A clear distinction was observed between studies conducted in the US and those in Europe, in favor of the latter. Today, no clear conclusions of the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints can be drawn. Further studies with larger study samples also assessing the long-term impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints are required to further strengthen the body of evidence.”

Some of the most obvious weaknesses of this review include the following:

- In none of the studies employed blinding of patients, care provider or outcome assessor occurred, or it was unclear. Blinding of outcome assessors is easily implemented and should be standard in any RCT.

- In three studies, the study groups differed to some extent at baseline indicating that randomisation was not successful..

- Five studies were derived from the ‘grey literature’ and were therefore not peer-reviewed.

- One study (the UK BEAM trial) employed not just osteopaths but also chiropractors and physiotherapists for administering the spinal manipulations. It is therefore hardly an adequate test of osteopathy.

- The study was funded by an unrestricted grant from the GNRPO, the umbrella organization of the ‘Belgian Professional Associations for Osteopaths’.

Considering this last point, the authors’ honesty in admitting that no clear conclusions of the impact of osteopathic care for spinal complaints can be drawn is remarkable and deserves praise.

Considering that the evidence for osteopathy is even far worse for non-spinal conditions (numerous trials exist for all sorts of other conditions, but they tend to be flimsy and usually lack independent replications), it is fair to conclude that osteopathy is NOT an evidence-based therapy.

Osteopathic visceral manipulation (OVM) have been our subject several times before. The method has been developed by the French Osteopath and Physical Therapist Jean-Pierre Barral. According to uncounted Internet-sites, books and other promotional literature, OVM is a miracle cure for just about every disease imaginable. Most of us hearing such claims hear alarm bells ringing – rightly so, I think. The evidence for OVM is thin, to put it mildly. But now, there is a new study to consider.

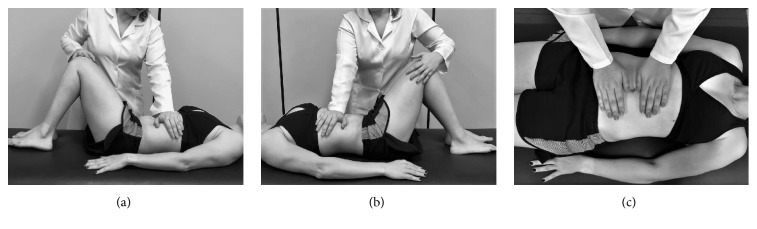

Brazilian researchers designed a placebo-controlled study using placebo visceral manipulation as the control to evaluate the effect of OVM of the stomach and liver on pain, cervical mobility, and electromyographic activity of the upper trapezius (UT) muscle in individuals with nonspecific neck pain (NS-NP) and functional dyspepsia. Twenty-eight NS-NP patients were randomly assigned into two groups: treated with OVM (OVMG; n = 14) and treated with placebo visceral manipulation (PVMG; n = 14). The effects were evaluated immediately and 7 days after treatment through pain, cervical range, and electromyographic activity of the UT muscle.

Significant effects were confirmed immediately after treatment (OVMG and PVMG) for numeric rating scale scores and pain area. Significant increases in EMG amplitude were identified immediately and 7 days after treatment for the OVMG. No differences were identified between the OVMG and the PVMG for cervical range of motion.

The authors concluded that the results of this pilot study indicate that a single session of osteopathic visceral manipulation for the stomach and liver reduces cervical pain and increases the amplitude of the upper trapezius muscle EMG signal immediately and 7 days after treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain and functional dyspepsia. Patients treated with placebo visceral mobilisation reported a significant decrease in pain immediately after treatment. The effect of this intervention on the cervical range of motion was inconclusive. The results of this study suggest that further investigation is necessary.

There are numerous problems with this study:

- The authors call it a pilot study. Such a trial is for exploring the feasibility of a proper study. With the introduction of a placebo-OVM, this would make sense. The relevant question would then be: is the placebo valid and indistinguishable from the real thing? Sadly, this issue is not even addressed in the trial.

- A pilot study certainly is not for evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention. Sadly, this is precisely what the authors used it for. The label ‘pilot’, it seems, was merely given to excuse the many methodological flaws of their trial.

- For an evaluation of treatment effects, the study was far too small. This means the reported results can be discarded as meaningless.

- If we nevertheless took them seriously, we would want to explain how the findings were generated. The authors believe that they were caused by OVM. I find this most unlikely.

- The more plausible explanation would be that patient-blinding was unsuccessful. In other words, the placebo is not indistinguishable from the real OVM. Looking at the pictures above, one can easily see that the patients were able to tell to which group they had been allocated.

- The failure to blind patients (and, of course, the therapists), in turn, would mean that the verum group were better motivated to out-perform the placebo group in the outcome measures.

- Finally, I disagree with the authors’ view that the results of this study suggest that further investigation is necessary. On the contrary, I think that any further investment into OVM is ill-advised.

My conclusion: OVM is an implausible, non-evidence-based SCAM, and dodgy science is not going to make it look any more convincing.

In 1995, Dabbs and Lauretti reviewed the risks of cervical manipulation and compared them to those of non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They concluded that the best evidence indicates that cervical manipulation for neck pain is much safer than the use of NSAIDs, by as much as a factor of several hundred times. This article must be amongst the most-quoted paper by chiropractors, and its conclusion has become somewhat of a chiropractic mantra which is being repeated ad nauseam. For instance, the American Chiropractic Association states that the risks associated with some of the most common treatments for musculoskeletal pain—over-the-counter or prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and prescription painkillers—are significantly greater than those of chiropractic manipulation.

As far as I can see, no further comparative safety-analyses between cervical manipulation and NSAIDs have become available since this 1995 article. It would therefore be time, I think, to conduct new comparative safety and risk/benefit analyses aimed at updating our knowledge in this important area.

Meanwhile, I will attempt a quick assessment of the much-quoted paper by Dabbs and Lauretti with a view of checking how reliable its conclusions truly are.

The most obvious criticism of this article has already been mentioned: it is now 23 years old, and today we know much more about the risks and benefits of these two therapeutic approaches. This point alone should make responsible healthcare professionals think twice before promoting its conclusions.

Equally important is the fact that we still have no surveillance system to monitor the adverse events of spinal manipulation. Consequently, our data on this issue are woefully incomplete, and we have to rely mostly on case reports. Yet, most adverse events remain unpublished and under-reporting is therefore huge. We have shown that, in our UK survey, it amounted to exactly 100%.

To make matters worse, case reports were excluded from the analysis of Dabbs and Lauretti. In fact, they included only articles providing numerical estimates of risk (even reports that reported no adverse effects at all), the opinion of exerts, and a 1993 statistic from a malpractice insurer. None of these sources would lead to reliable incidence figures; they are thus no adequate basis for a comparative analysis.

In contrast, NSAIDs have long been subject to proper post-marketing surveillance systems generating realistic incidence figures of adverse effects which Dabbs and Lauretti were able to use. It is, however, important to note that the figures they did employ were not from patients using NSAIDs for neck pain. Instead they were from patients using NSAIDs for arthritis. Equally important is the fact that they refer to long-term use of NSAIDs, while cervical manipulation is rarely applied long-term. Therefore, the comparison of risks of these two approaches seems not valid.

Moreover, when comparing the risks between cervical manipulation and NSAIDs, Dabbs and Lauretti seemed to have used incidence per manipulation, while for NSAIDs the incidence figures were bases on events per patient using these drugs (the paper is not well-constructed and does not have a methods section; thus, it is often unclear what exactly the authors did investigate and how). Similarly, it remains unclear whether the NSAID-risk refers only to patients who had used the prescribed dose, or whether over-dosing (a phenomenon that surely is not uncommon with patients suffering from chronic arthritis pain) was included in the incidence figures.

It is worth mentioning that the article by Dabbs and Lauretti refers to neck pain only. Many chiropractors have in the past broadened its conclusions to mean that spinal manipulations or chiropractic care are safer than drugs. This is clearly not permissible without sound data to support such claims. As far as I can see, such data do not exist (if anyone knows of such evidence, I would be most thankful to let me see it).

To obtain a fair picture of the risks in a real life situation, one should perhaps also mention that chiropractors often fail to warn patients of the possibility of adverse effects. With NSAIDs, by contrast, patients have, at the very minimum, the drug information leaflets that do warn them of potential harm in full detail.

Finally, one could argue that the effectiveness and costs of the two therapies need careful consideration. The costs for most NSAIDs per day are certainly much lower than those for repeated sessions of manipulations. As to the effectiveness of the treatments, it is clear that NSAIDs do effectively alleviate pain, while the evidence seems far from being conclusively positive in the case of cervical manipulation.

In conclusion, the much-cited paper by Dabbs and Lauretti is out-dated, poor quality, and heavily biased. It provides no sound basis for an evidence-based judgement on the relative risks of cervical manipulation and NSAIDs. The notion that cervical manipulations are safer than NSAIDs is therefore not based on reliable data. Thus, it is misleading and irresponsible to repeat this claim.

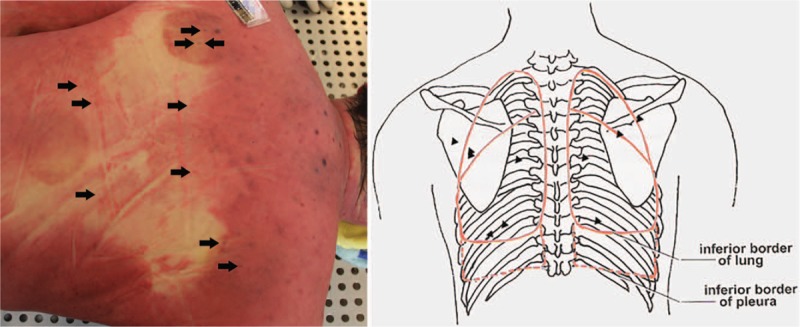

The most frequent of all potentially serious adverse events of acupuncture is pneumothorax. It happens when an acupuncture needle penetrates the lungs which subsequently deflate. The pulmonary collapse can be partial or complete as well as one or two sided. This new case-report shows just how serious a pneumothorax can be.

A 52-year-old man underwent acupuncture and cupping treatment at an illegal Chinese medicine clinic for neck and back discomfort. Multiple 0.25 mm × 75 mm needles were utilized and the acupuncture points were located in the middle and on both sides of the upper back and the middle of the lower back. He was admitted to hospital with severe dyspnoea about 30 hours later. On admission, the patient was lucid, was gasping, had apnoea and low respiratory murmur, accompanied by some wheeze in both sides of the lungs. Because of the respiratory difficulty, the patient could hardly speak. After primary physical examination, he was suspected of having a foreign body airway obstruction. Around 30 minutes after admission, the patient suddenly became unconscious and died despite attempts of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Whole-body post-mortem computed tomography of the victim revealed the collapse of the both lungs and mediastinal compression, which were also confirmed by autopsy. More than 20 pinprick injuries were found on the skin of the upper and lower back in which multiple pinpricks were located on the body surface projection of the lungs. The cause of death was determined as acute respiratory and circulatory failure due to acupuncture-induced bilateral tension pneumothorax.

The authors caution that acupuncture-induced tension pneumothorax is rare and should be recognized by forensic pathologists. Postmortem computed tomography can be used to detect and accurately evaluate the severity of pneumothorax before autopsy and can play a supporting role in determining the cause of death.

The authors mention that pneumothorax is the most frequent but by no means the only serious complication of acupuncture. Other adverse events include:

- central nervous system injury,

- infection,

- epidural haematoma,

- subarachnoid haemorrhage,

- cardiac tamponade,

- gallbladder perforation,

- hepatitis.

No other possible lung diseases that may lead to bilateral spontaneous pneumothorax were found. The needles used in the case left tiny perforations in the victim’s lungs. A small amount of air continued to slowly enter the chest cavities over a long period. The victim possibly tolerated the mild discomfort and did not pay attention when early symptoms appeared. It took 30 hours to develop into symptoms of a severe pneumothorax, and then the victim was sent to the hospital. There he was misdiagnosed, not adequately treated and thus died. I applaud the authors for nevertheless publishing this case-report.

This case occurred in China. Acupuncturists might argue that such things would not happen in Western countries where acupuncturists are fully trained and aware of the danger. They would be mistaken – and alarmingly, there is no surveillance system that could tell us how often serious complications occur.

A pain in the neck is just that: A PAIN IN THE NECK! Unfortunately, this symptom is both common and often difficult to treat. Chiropractors pride themselves of treating neck pain effectively. Yet, the evidence is at best thin, the costs are high and, as often-discussed, the risks might be considerable. Thus, any inexpensive, effective and safe alternative would be welcome.

This RCT tested two hypotheses:

1) that denneroll cervical traction (a very simple device for the rehabilitation of sagittal cervical alignment) will improve the sagittal alignment of the cervical spine.

2) that restoration of normal cervical sagittal alignment will improve both short and long-term outcomes in cervical myofascial pain syndrome patients.

The study included 120 (76 males) patients with chronic myofascial cervical pain syndrome (CMCPS) and defined cervical sagittal posture abnormalities. They were randomly assigned to the control or an intervention group. Both groups received the Integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique (INIT); additionally, the intervention group received the denneroll cervical traction device. Alignment outcomes included two measures of sagittal posture: cervical angle (CV), and shoulder angle (SH). Patient relevant outcome measures included: neck pain intensity (NRS), neck disability (NDI), pressure pain thresholds (PPT), cervical range of motion using the CROM. Measures were assessed at three intervals: baseline, 10 weeks, and 1 year after the 10 week follow up.

After 10 weeks of treatment, between group statistical analysis, showed equal improvements for both the intervention and control groups in NRS and NDI. However, at 10 weeks, there were significant differences between groups favouring the intervention group for PPT and all measures of CROM. Additionally, at 10 weeks the sagittal alignment variables showed significant differences favouring the intervention group for CV and SH indicating improved CSA. Importantly, at the 1-year follow-up, between group analysis identified a regression back to baseline values for the control group for the non-significant group differences (NRS and NDI) at the 10-week mark. Thus, all variables were significantly different between groups favouring the intervention group at 1-year follow up.

The authors concluded that the addition of the denneroll cervical orthotic to a multimodal program positively affected CMCPS outcomes at long term follow up. We speculate the improved sagittal cervical posture alignment outcomes contributed to our findings.

Yes, I know, this study is far from rigorous or conclusive. And the evidence for traction is largely negative. But the device has one huge advantage over chiropractic: it cannot cause much harm. The harm to the wallet is less than that of endless sessions chiropractors or other manual therapists (conceivably, a self-made cushion will have similar effects without any expense); and the chances that patients suffer a stroke are close to zero.

On this blog, I have repeatedly discussed chiropractic research that, on closer examination, turns out to be some deplorable caricature of science. Today, I have another example of what I would call pseudo-research.

This RCT compared short-term treatment (12 weeks) versus long-term management (36 weeks) of back and neck related disability in older adults using spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) combined with supervised rehabilitative exercises (SRE).

Eligible participants were aged 65 and older with back and neck disability for more than 12 weeks. Co-primary outcomes were changes in Oswestry and Neck Disability Index after 36 weeks. An intention to treat approach used linear mixed-model analysis to detect between group differences. Secondary analyses included other self-reported outcomes, adverse events and objective functional measures.

A total of 182 participants were randomized. The short-term and long-term groups demonstrated significant improvements in back and neck disability after 36 weeks, with no difference between groups. The long-term management group experienced greater improvement in neck pain at week 36, self-efficacy at week 36 and 52, functional ability and balance.

The authors concluded that for older adults with chronic back and neck disability, extending management with SMT and SRE from 12 to 36 weeks did not result in any additional important reduction in disability.

What renders this paper particularly fascinating is the fact that its authors include some of the foremost researchers in (and most prominent proponents of) chiropractic today. I therefore find it interesting to critically consider the hypothesis on which this seemingly rigorous study is based.

As far as I can see, it essentially is this:

36 weeks of chiropractic therapy plus exercise leads to better results than 12 weeks of the same treatment.

I find this a most remarkable hypothesis.

Imagine any other form of treatment that is, like SMT, not solidly based on evidence of efficacy. Let’s use a new drug as an example, more precisely a drug for which there is no solid evidence for efficacy or safety. Now let’s assume that the company marketing this drug publishes a trial based on the hypothesis that:

36 weeks of therapy with the new drug plus exercise leads to better results than 12 weeks of the same treatment.

Now let’s assume the authors affiliated with the drug manufacturer concluded from their findings that for patients with chronic back and neck disability, extending drug therapy plus exercise from 12 to 36 weeks did not result in any additional important reduction in disability.

WHAT DO YOU THINK SUCH A TRIAL CAN TELL US?

My answer is ‘next to nothing’.

I think, it merely tells us that

- daft hypotheses lead to daft research,

- even ‘top’ chiropractors have problems with critical thinking,

- SMT might not be the solution to neck and back related disability.

I REST MY CASE.

This study was aimed at evaluating group-level and individual-level change in health-related quality of life among persons with chronic low back pain or neck pain receiving chiropractic care in the United States.

A 3-month longitudinal study was conducted of 2,024 patients with chronic low back pain or neck pain receiving care from 125 chiropractic clinics at 6 locations throughout the US. Ninety-one percent of the sample completed the baseline and 3-month follow-up survey (n = 1,835). Average age was 49, 74% females, and most of the sample had a college degree, were non-Hispanic White, worked full-time, and had an annual income of $60,000 or more. Group-level and individual-level changes on the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) v2.0 profile measure were evaluated: 6 multi-item scales (physical functioning, pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, social health, emotional distress) and physical and mental health summary scores.

Within group t-tests indicated significant group-level change for all scores except for emotional distress, and these changes represented small improvements in health. From 13% (physical functioning) to 30% (PROMIS-29 Mental Health Summary Score) got better from baseline to 3 months later.

The authors concluded that chiropractic care was associated with significant group-level improvement in health-related quality of life over time, especially in pain. But only a minority of the individuals in the sample got significantly better (“responders”). This study suggests some benefits of chiropractic on functioning and well-being of patients with low back pain or neck pain.

These conclusions are worded carefully to avoid any statement of cause and effect. But I nevertheless feel that the authors strongly imply that chiropractic caused the observed outcomes. This is perhaps most obvious when they state that this study suggests some benefits of chiropractic on functioning and well-being of patients with low back pain or neck pain.

To me, it is obvious that this is wrong. The data are just as consistent with the opposite conclusion. There was no control group. It is therefore conceivable that the patients would have improved more and/or faster, if they had never consulted a chiropractor. The devil’s advocate therefore concludes this: the results of this study suggest that chiropractic has significant detrimental effects on functioning and well-being of patients with low back pain or neck pain.

Try to prove me wrong!

PS

I am concerned that a leading journal (Spine) publishes such rubbish.

Do musculoskeletal conditions contribute to chronic non-musculoskeletal conditions? The authors of a new paper – inspired by chiropractic thinking, it seems – think so. Their meta-analysis was aimed to investigate whether the most common musculoskeletal conditions, namely neck or back pain or osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, contribute to the development of chronic disease.

The authors searched several electronic databases for cohort studies reporting adjusted estimates of the association between baseline neck or back pain or osteoarthritis of the knee or hip and subsequent diagnosis of a chronic disease (cardiovascular disease , cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease or obesity).

There were 13 cohort studies following 3,086,612 people. In the primary meta-analysis of adjusted estimates, osteoarthritis (n= 8 studies) and back pain (n= 2) were the exposures and cardiovascular disease (n=8), cancer (n= 1) and diabetes (n= 1) were the outcomes. Pooled adjusted estimates from these 10 studies showed that people with a musculoskeletal condition have a 17% increase in the rate of developing a chronic disease compared to people without a musculoskeletal condition.

The authors concluded that musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease. In particular, osteoarthritis appears to increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Prevention and early

treatment of musculoskeletal conditions and targeting associated chronic disease risk factors in people with long

standing musculoskeletal conditions may play a role in preventing other chronic diseases. However, a greater

understanding about why musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease is needed.

For the most part, this paper reads as if the authors are trying to establish a causal relationship between musculoskeletal problems and systemic diseases at all costs. Even their aim (to investigate whether the most common musculoskeletal conditions, namely neck or back pain or osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, contribute to the development of chronic disease) clearly points in that direction. And certainly, their conclusion that musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease confirms this suspicion.

In their discussion, they do concede that causality is not proven: While our review question ultimately sought to assess a causal connection between common musculoskeletal conditions and chronic disease, we cannot draw strong conclusions due to poor adjustment, the analysis methods employed by the included studies, and a lack of studies investigating conditions other than OA and cardiovascular disease…We did not find studies that satisfied all of Bradford Hill’s suggested criteria for casual inference (e.g. none estimated dose–response effects) nor did we find studies that used contemporary causal inference methods for observational data (e.g. a structured identification approach for selection of confounding variables or assessment of the effects of unmeasured or residual confounders. As such, we are unable to infer a strong causal connection between musculoskeletal conditions and chronic diseases.

In all honesty, I would see this a little differently: If their review question ultimately sought to assess a causal connection between common musculoskeletal conditions and chronic disease, it was quite simply daft and unscientific. All they could ever hope is to establish associations. Whether these are causal or not is an entirely different issue which is not answerable on the basis of the data they searched for.

An example might make this clearer: people who have yellow stains on their 2nd and 3rd finger often get lung cancer. The yellow fingers are associated with cancer, yet the link is not causal. The association is due to the fact that smoking stains the fingers and causes cancer. What the authors of this new article seem to suggest is that, if we cut off the stained fingers of smokers, we might reduce the cancer risk. This is clearly silly to the extreme.

So, how might the association between musculoskeletal problems and systemic diseases come about? Of course, the authors might be correct and it might be causal. This would delight chiropractors because DD Palmer, their founding father, said that 95% of all diseases are caused by subluxation of the spine, the rest by subluxations of other joints. But there are several other and more likely explanations for this association. For instance, many people with a systemic disease might have had subclinical problems for years. These problems would prevent them from pursuing a healthy life-style which, in turn, resulted is musculoskeletal problems. If this is so, musculoskeletal conditions would not increase the risk of chronic disease, but chronic diseases would lead to musculoskeletal problems.

Don’t get me wrong, I am not claiming that this reverse causality is the truth; I am simply saying that it is one of several possibilities that need to be considered. The fact that the authors failed to do so, is remarkable and suggests that they were bent on demonstrating what they put in their conclusion. And that, to me, is an unfailing sign of poor science.

It is no secret to regular readers of this blog that chiropractic’s effectiveness is unproven for every condition it is currently being promoted for – perhaps with two exceptions: neck pain and back pain. Here we have some encouraging data, but also lots of negative evidence. A new US study falls into the latter category; I am sure chiropractors will not like it, but it does deserve a mention.

This study evaluated the comparative effectiveness of usual care with or without chiropractic care for patients with chronic recurrent musculoskeletal back and neck pain. It was designed as a prospective cohort study using propensity score-matched controls.

Using retrospective electronic health record data, the researchers developed a propensity score model predicting likelihood of chiropractic referral. Eligible patients with back or neck pain were then contacted upon referral for chiropractic care and enrolled in a prospective study. For each referred patient, two propensity score-matched non-referred patients were contacted and enrolled. We followed the participants prospectively for 6 months. The main outcomes included pain severity, interference, and symptom bothersomeness. Secondary outcomes included expenditures for pain-related health care.

Both groups’ (N = 70 referred, 139 non-referred) pain scores improved significantly over the first 3 months, with less change between months 3 and 6. No significant between-group difference was observed. After controlling for variances in baseline costs, total costs during the 6-month post-enrollment follow-up were significantly higher on average in the non-referred versus referred group. Adjusting for differences in age, gender, and Charlson comorbidity index attenuated this finding, which was no longer statistically significant (p = .072).

The authors concluded by stating this: we found no statistically significant difference between the two groups in either patient-reported or economic outcomes. As clinical outcomes were similar, and the provision of chiropractic care did not increase costs, making chiropractic services available provided an additional viable option for patients who prefer this type of care, at no additional expense.

This comes from some of the most-renowned experts in back pain research, and it is certainly an elaborate piece of investigation. Yet, I find the conclusions unreasonable.

Essentially, the authors found that chiropractic has no clinical or economical advantage over other approaches currently used for neck and back pain. So, they say that it a ‘viable option’.

I find this odd and cannot quite follow the logic. In my view, it lacks critical thinking and an attempt to produce progress. If it is true that all treatments were similarly (in)effective – which I can well believe – we still should identify those that have the least potential for harm. That could be exercise, massage therapy or some other modality – but I don’t think it would be chiropractic care.

References

Elder C, DeBar L, Ritenbaugh C, Dickerson J, Vollmer WM, Deyo RA, Johnson ES, Haas M.

J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4539-y. [Epub ahead of print]

PMID: 29943109