migraine

NICE helps practitioners and commissioners get the best care to patients, fast, while ensuring value for the taxpayer. Internationally, NICE has a reputation for being reliable and trustworthy. But is that also true for its recommendations regarding the use of acupuncture? NICE currently recommends that patients consider acupuncture as a treatment option for the following conditions:

- chronic (long-term) pain

- chronic tension-type headaches

- migraines

- prostatitis symptoms

- hiccups

Confusingly, on a different site, NICE also recommends acupuncture for retinal migraine, a very specific type of migraine that affect normally just one eye with symptoms such as vision loss lasting up to one hour, a blind spot in the vision, headache, blurred vision and seeing flashing lights, zigzag patterns or coloured spots or lines, as well as feeling nauseous or being sick.

I think this perplexing situation merits a look at the evidence. Here I quote the conclusions of recent, good quality, and (where possible) independent reviews:

- Chronic pain: Acupuncture is efficacious for reducing pain in patients with LBP… Further research needs to be done to evaluate acupuncture’s efficacy in these conditions, especially for abdominal pain, as many of the current studies have a risk of bias due to lack of blinding and small sample size.

- Chronic tension-type headaches (TTH): Acupuncture may be an effective and safe treatment for TTH patients. Due to low or very low certainty of evidence and high heterogeneity, more rigorous RCTs are needed to verify the effect and safety of acupuncture in the management of TTH.

- Migraines: Many studies suggest that acupuncture is a safe, helpful and available alternative therapy that may be beneficial to certain migraine patients. Nevertheless, further large-scale RCTs are warranted to further consolidate these findings and provide further support for the clinical value of acupuncture. Despite previous studies that have analyzed the effects of acupuncture on migraine, there is still a need for further investigation to ensure that the incorporation of acupuncture into migraine treatment management will have a positive outcome on patients.

- Prostatitis: This meta-analysis indicated that acupuncture has measurable benefits on CP/CPPS, and security has also been ensured. However, this meta-analysis only included 10 RCTs; thus, RCTs with a larger sample size and longer-term observation are required to verify the effectiveness of acupuncture further in the future.

- Hiccups: All of these studies sought to determine the effectiveness of different acupuncture techniques in the treatment of persistent and intractable hiccups. All four studies had a high risk of bias, did not compare the intervention with placebo, and failed to report side effects or adverse events for either the treatment or control groups.

- Retinal migraine: no evidence

So, what do we make of this? I think that, on the basis of the evidence:

- a positive recommendation for all types of chromic pain is not warranted;

- a positive recommendation for the treatment of TTH is questionable;

- a positive recommendation for migraine is questionable;

- a positive recommendation for prostatitis is questionable;

- a positive recommendation for hiccups is not warranted;

- a positive recommendation for retinal migraine is not warranted.

But why did NICE issue positive recommendations despite weak or even non-existent evidence?

SEARCH ME!

.

The ‘American Heart Association News’ recently reported the case of a 33-year-old woman who suffered a stroke after consulting a chiropractor. I take the liberty of reproducing sections of this article:

Kate Adamson liked exercising so much, her goal was to become a fitness trainer. She grew up in New Zealand playing golf and later, living in California, she worked out often while raising her two young daughters. Although she was healthy and ate well, she had occasional migraines. At age 33, they were getting worse and more frequent. One week, she had the worst headache of her life. It went on for days. She wasn’t sleeping well and got up early to take a shower. She felt a wave of dizziness. Her left side seemed to collapse. Adamson made her way down to the edge of the tub to rest. She was able to return to bed, where she woke up her husband, Steven Klugman. “I need help now,” she said.

Her next memory was seeing paramedics rushing into the house while her 3-year-old daughter, Stephanie, was in the arms of a neighbor. Rachel, her other daughter, then 18 months old, was still asleep. When she woke up in the hospital, Adamson found herself surrounded by doctors. Klugman was by her side. She could see them, hear them and understand them. But she could not move or react.

Doctors told Klugman that his wife had experienced a massive brain stem stroke. It was later thought to be related to neck manipulations she had received from a chiropractor for the migraines. The stroke resulted in what’s known as locked-in syndrome, a disorder of the nervous system. She was paralyzed except for the muscles that control eye movement. Adamson realized she could answer yes-or-no questions by blinking her eyes.

Klugman was told that Adamson had a very minimal chance of recovery. She was put on a ventilator to breathe, given nutrition through a feeding tube, and had to use a catheter. She learned to coordinate eye movements to an alphabet chart. This enabled her to make short sentences. “Am I going to die?” she asked one of her doctors. “No, we’re going to get you into rehab,” he said.

Adamson stayed in the ICU on life support for 70 days before being transferred to an acute rehabilitation facility. She could barely move a finger, but that small bit of progress gave her hope. In rehab, she slowly started to regain use of her right side; her left side remained paralyzed. Therapists taught her to swallow and to speak. She had to relearn to blow her nose, use the toilet and tie her shoes.

She was particularly fond of a social worker named Amy who would incorporate therapy exercises into visits with her children, such as bubble blowing to help her breathing. Amy, who Adamson became friends with, also helped the children adjust to seeing their mother in a wheelchair.

Adamson changed her dream job from fitness trainer to hospital social worker. She left rehab three and a half months later, still in a wheelchair but able to breathe, eat and use the toilet on her own. She continued outpatient rehab for another year. She assumed her left side would improve as her right side did. But it remained paralyzed. She would need to use a brace on her left leg to walk and couldn’t use her left arm and hand. Still, two years after the stroke, which happened in 1995, Adamson was able to drive with a few equipment modifications…

In 2018, Adamson reached another milestone. She graduated with a master’s degree in social work; she’d started college in 2011 at age 49. “It wasn’t easy going to school. I just had to take it a day at a time, a semester at a time,” she said. “The stroke has taught me I can walk through anything.” …

Now 60, she works with renal transplant and pulmonary patients, helping coordinate their services and care with the rest of the medical team at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “Knowing that you’re making a difference in somebody’s life is very satisfying. It takes me back to when I was a patient – I’m always looking at how I would want to be treated,” she said. “I’ve really come full circle.”

Adamson has adapted to doing things one-handed in a two-handed world, such as cooking and tying her shoes. She also walks with a cane. To stay in shape, she works with a trainer doing functional exercises and strength training. She has a special glove that pulls her left hand into a fist, allowing her to use a rowing machine and stationary bike….

Adamson is especially determined when it comes to helping her patients. “I work really hard to be an example to them, to show that we are all capable of going through difficult life challenges while still maintaining a positive attitude and making a difference in the world.”

________________________

What can we learn from this story?

Mainly two things, in my view:

- We probably should avoid chiropractors and certainly not allow them to manipulate our necks. I know, chiros will say that the case proves nothing. I agree, it does not prove anything, but the mere suspicion that the lock-in syndrome was caused by a stroke that, in turn, was due to upper spinal manipulation plus the plethora of cases where causality is much clearer are, I think, enough to issue that caution.

- Having been in rehab medicine for much of my early career, I feel it is good to occasionally point out how important this sector often neglected part of healthcare can be. Rehab medicine has been a sensible form of multidisciplinary, integrative healthcare long before the enthusiasts of so-called alternative medicine jumped on the integrative bandwagon.

Migraines are common headache disorders and risk factors for subsequent strokes. Acupuncture has been widely used in the treatment of migraines; however, few studies have examined whether its use reduces the risk of strokes in migraineurs. This study explored the long-term effects of acupuncture treatment on stroke risk in migraineurs using national real-world data.

A team of Taiwanese researchers collected new migraine patients from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2017. Using 1:1 propensity-score matching, they assigned patients to either an acupuncture or non-acupuncture cohort and followed up until the end of 2018. The incidence of stroke in the two cohorts was compared using the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Each cohort was composed of 1354 newly diagnosed migraineurs with similar baseline characteristics. Compared with the non-acupuncture cohort, the acupuncture cohort had a significantly reduced risk of stroke (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.35–0.46). The Kaplan–Meier model showed a significantly lower cumulative incidence of stroke in migraine patients who received acupuncture during the 19-year follow-up (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

The authors concluded that acupuncture confers protective benefits on migraineurs by reducing the risk of stroke. Our results provide new insights for clinicians and public health experts.

After merely 10 minutes of critical analysis, ‘real-world data’ turn out to be real-bias data, I am afraid.

The first question to ask is, were the groups at all comparable? The answer is, NO; the acupuncture group had

- more young individuals;

- fewer laborers;

- fewer wealthy people;

- fewer people with coronary heart disease;

- fewer individuals with chronic kidney disease;

- fewer people with mental disorders;

- more individuals taking multiple medications.

And that are just the variables that were known to the researcher! There will be dozens that are unknown but might nevertheless impact on a stroke prognosis.

But let’s not be petty and let’s forget (for a minute) about all these inequalities that render the two groups difficult to compare. The potentially more important flaw in this study lies elsewhere.

Imagine a group of people who receive some extra medical attention – such as acupuncture – over a long period of time, administered by a kind and caring therapist; imagine you were one of them. Don’t you think that it is likely that, compared to other people who do not receive this attention, you might feel encouraged to look better after your health? Consequently, you might do more exercise, eat more healthily, smoke less, etc., etc. As a result of such behavioral changes, you would be less likely to suffer a stroke, never mind the acupuncture.

SIMPLE!

I am not saying that such studies are totally useless. What often renders them worthless or even dangerous is the fact that the authors are not more self-critical and don’t draw more cautious conclusions. In the present case, already the title of the article says it all:

Acupuncture Is Effective at Reducing the Risk of Stroke in Patients with Migraines: A Real-World, Large-Scale Cohort Study with 19-Years of Follow-Up

My advice to researchers of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and journal editors publishing their papers is this: get your act together, learn about the pitfalls of flawed science (most of my books might assist you in this process), and stop misleading the public. Do it sooner rather than later!

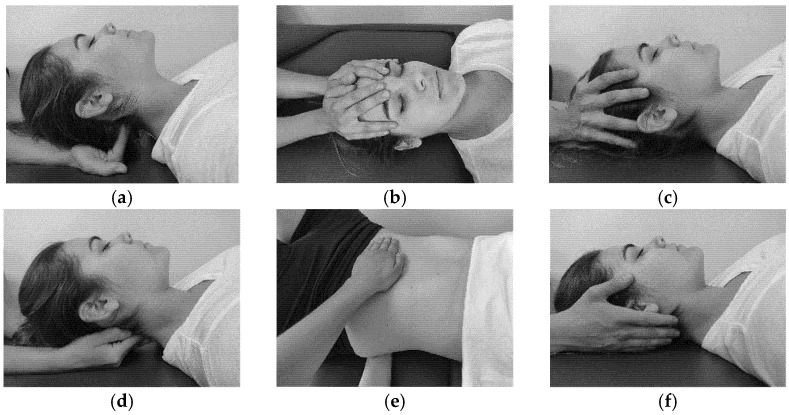

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of craniosacral therapy on different features in migraine patients.

Fifty individuals with migraine were randomly divided into two groups (n = 25 per group):

- craniosacral therapy group (CTG),

- sham control group (SCG).

The interventions were carried out with the patient in the supine position. The CTG received a manual therapy treatment focused on the craniosacral region including five techniques, and the SCG received a hands-on placebo intervention. After the intervention, individuals remained supine with a neutral neck and head position for 10 min, to relax and diminish tension after treatment. The techniques were executed by the same experienced physiotherapist in both groups.

The analyzed variables were pain, migraine severity, and frequency of episodes, functional, emotional, and overall disability, medication intake, and self-reported perceived changes, at baseline, after a 4-week intervention, and at an 8-week follow-up.

After the intervention, the CTG significantly reduced pain (p = 0.01), frequency of episodes (p = 0.001), functional (p = 0.001) and overall disability (p = 0.02), and medication intake (p = 0.01), as well as led to a significantly higher self-reported perception of change (p = 0.01), when compared to SCG. The results were maintained at follow-up evaluation in all variables.

The authors concluded that a protocol based on craniosacral therapy is effective in improving pain, frequency of episodes, functional and overall disability, and medication intake in migraineurs. This protocol may be considered as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients.

Sorry, but I disagree!

And I have several reasons for it:

- The study was far too small for such strong conclusions.

- For considering any treatment as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients, we would need at least one independent replication.

- There is no plausible rationale for craniosacral therapy to work for migraine.

- The blinding of patients was not checked, and it is likely that some patients knew what group they belonged to.

- There could have been a considerable influence of the non-blinded therapists on the outcomes.

- There was a near-total absence of a placebo response in the control group.

Altogether, the findings seem far too good to be true.

Two recent reviews have evaluated the evidence for acupuncture as a means of preventing migraine attacks.

The first review assessed the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of episodic or chronic migraine in adult patients compared to pharmacological treatment.

The authors included randomized controlled trials published in western languages that compared any treatment involving needle insertion (with or without manual or electrical stimulation) at acupuncture points, pain points or trigger points, with any pharmacological prophylaxis in adult (≥18 years) with chronic or episodic migraine with or without aura according to the criteria of the International Headache Society.

Nine randomized trials were included encompassing 1,484 patients. At the end of the intervention, a small reduction was found in favor of acupuncture for the number of days with migraine per month: (SMD: -0.37; 95% CI -1.64 to -0.11), and for response rate (RR: 1.46; 95% CI 1.16-1.84). A moderate effect emerged in the reduction of pain intensity in favor of acupuncture (SMD: -0.36; 95% CI -0.60 to -0.13), and a large reduction in favor of acupuncture in both the dropout rate due to any reason (RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.84) and the dropout rate due to adverse event (RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.74). The quality of the evidence was moderate for all these primary outcomes. Results at longest follow-up confirmed these effects.

The authors concluded that, based on moderate certainty of evidence, we conclude that acupuncture is mildly more effective and much safer than medication for the prophylaxis of migraine.

The second review aimed to perform a network meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness and acceptability between topiramate, acupuncture, and Botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT-A).

The authors searched OVID Medline, Embase, the Cochrane register of controlled trials (CENTRAL), the Chinese Clinical Trial Register, and clinicaltrials.gov for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared topiramate, acupuncture, and BoNT-A with any of them or placebo in the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. A network meta-analysis was performed by using a frequentist approach and a random-effects model. The primary outcomes were the reduction in monthly headache days and monthly migraine days at week 12. Acceptability was defined as the number of dropouts owing to adverse events.

A total of 15 RCTs (n = 2545) could be included. Eleven RCTs were at low risk of bias. The network meta-analyses (n = 2061) showed that acupuncture (2061 participants; standardized mean difference [SMD] -1.61, 95% CI: -2.35 to -0.87) and topiramate (582 participants; SMD -0.4, 95% CI: -0.75 to -0.04) ranked the most effective in the reduction of monthly headache days and migraine days, respectively; but they were not significantly superior over BoNT-A. Topiramate caused the most treatment-related adverse events and the highest rate of dropouts owing to adverse events.

The authors concluded that Topiramate and acupuncture were not superior over BoNT-A; BoNT-A was still the primary preventive treatment of chronic migraine. Large-scale RCTs with direct comparison of these three treatments are warranted to verify the findings.

Unquestionably, these are interesting findings. How reliable are they? Acupuncture trials are in several ways notoriously tricky, and many of the primary studies were of poor quality. This means the results are not as reliable as one would hope. Yet, it seems to me that migraine prevention is one of the indications where the evidence for acupuncture is strongest.

A second question might be practicability. How realistic is it for a patient to receive regular acupuncture sessions for migraine prevention? And finally, we might ask how cost-effective acupuncture is for that purpose and how its cost-effectiveness compares to other options.

The objective of this trial, just published in the BMJ, was to assess the efficacy of manual acupuncture as prophylactic treatment for acupuncture naive patients with episodic migraine without aura. The study was designed as a multi-centre, randomised, controlled clinical trial with blinded participants, outcome assessment, and statistician. It was conducted in 7 hospitals in China with 150 acupuncture naive patients with episodic migraine without aura.

They were given the following treatments:

- 20 sessions of manual acupuncture at true acupuncture points plus usual care,

- 20 sessions of non-penetrating sham acupuncture at heterosegmental non-acupuncture points plus usual care,

- usual care alone over 8 weeks.

The main outcome measures were change in migraine days and migraine attacks per 4 weeks during weeks 1-20 after randomisation compared with baseline (4 weeks before randomisation).

A total of 147 were included in the final analyses. Compared with sham acupuncture, manual acupuncture resulted in a significantly greater reduction in migraine days at weeks 13 to 20 and a significantly greater reduction in migraine attacks at weeks 17 to 20. The reduction in mean number of migraine days was 3.5 (SD 2.5) for manual versus 2.4 (3.4) for sham at weeks 13 to 16 and 3.9 (3.0) for manual versus 2.2 (3.2) for sham at weeks 17 to 20. At weeks 17 to 20, the reduction in mean number of attacks was 2.3 (1.7) for manual versus 1.6 (2.5) for sham. No severe adverse events were reported. No significant difference was seen in the proportion of patients perceiving needle penetration between manual acupuncture and sham acupuncture (79% v 75%).

The authors concluded that twenty sessions of manual acupuncture was superior to sham acupuncture and usual care for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine without aura. These results support the use of manual acupuncture in patients who are reluctant to use prophylactic drugs or when prophylactic drugs are ineffective, and it should be considered in future guidelines.

Considering the many flaws in most acupuncture studies discussed ad nauseam on this blog, this is a relatively rigorous trial. Yet, before we accept the conclusions, we ought to evaluate it critically.

The first thing that struck me was the very last sentence of its abstract. I do not think that a single trial can ever be a sufficient reason for changing existing guidelines. The current Cochrance review concludes that the available evidence suggests that adding acupuncture to symptomatic treatment of attacks reduces the frequency of headaches. Thus, one could perhaps argue that, together with the existing data, this new study might strengthen its conclusion.

In the methods section, the authors state that at the end of the study, we determined the maintenance of blinding of patients by asking them whether they thought the needles had penetrated the skin. And in the results section, they report that they found no significant difference between the manual acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups for patients’ ability to correctly guess their allocation status.

I find this puzzling, since the authors also state that they tried to elicit acupuncture de-qi sensation by the manual manipulation of needles. They fail to report data on this but this attempt is usually successful in the majority of patients. In the control group, where non-penetrating needles were used, no de-qi could be generated. This means that the two groups must have been at least partly de-blinded. Yet, we learn from the paper that patients were not able to guess to which group they were randomised. Which statement is correct?

This may sound like a trivial matter, but I fear it is not.

Like this new study, acupuncture trials frequently originate from China. We and others have shown that Chinese trials of acupuncture hardly ever produce a negative finding. If that is so, one does not need to read the paper, one already knows that it is positive before one has even seen it. Neither do the researchers need to conduct the study, one already knows the result before the trial has started.

You don’t believe the findings of my research nor those of others?

Excellent! It’s always good to be sceptical!

But in this case, do you believe Chinese researchers?

In this systematic review, all RCTs of acupuncture published in Chinese journals were identified by a team of Chinese scientists. An impressive total of 840 trials were found. Among them, 838 studies (99.8%) reported positive results from primary outcomes and two trials (0.2%) reported negative results. The authors concluded that publication bias might be major issue in RCTs on acupuncture published in Chinese journals reported, which is related to high risk of bias. We suggest that all trials should be prospectively registered in international trial registry in future.

So, at least three independent reviews have found that Chinese acupuncture trials report virtually nothing but positive findings. Is that enough evidence to distrust Chinese TCM studies?

Perhaps not!

But there are even more compelling reasons for taking evidence from China with a pinch of salt:

A survey of clinical trials in China has revealed fraudulent practice on a massive scale. China’s food and drug regulator carried out a one-year review of clinical trials. They concluded that more than 80 percent of clinical data is “fabricated“. The review evaluated data from 1,622 clinical trial programs of new pharmaceutical drugs awaiting regulator approval for mass production. According to the report, much of the data gathered in clinical trials are incomplete, failed to meet analysis requirements or were untraceable. Some companies were suspected of deliberately hiding or deleting records of adverse effects, and tampering with data that did not meet expectations. “Clinical data fabrication was an open secret even before the inspection,” the paper quoted an unnamed hospital chief as saying. Chinese research organisations seem have become “accomplices in data fabrication due to cutthroat competition and economic motivation.”

So, am I claiming the new acupuncture study just published in the BMJ is a fake?

No!

Am I saying that it would be wise to be sceptical?

Yes.

Sadly, my scepticism is not shared by the BMJ’s editorial writer who concludes that the new study helps to move acupuncture from having an unproven status in complementary medicine to an acceptable evidence based treatment.

Call me a sceptic, but that statement is, in my view, hard to justify!

Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (CSMT) for migraine?

Why?

There is no good evidence that it works!

On the contrary, there is good evidence that it does NOT work!

A recent and rigorous study (conducted by chiropractors!) tested the efficacy of chiropractic CSMT for migraine. It was designed as a three-armed, single-blinded, placebo -controlled RCT of 17 months duration including 104 migraineurs with at least one migraine attack per month. Active treatment consisted of CSMT (group 1) and the placebo was a sham push manoeuvre of the lateral edge of the scapula and/or the gluteal region (group 2). The control group continued their usual pharmacological management (group 3). The results show that migraine days were significantly reduced within all three groups from baseline to post-treatment. The effect continued in the CSMT and placebo groups at all follow-up time points (groups 1 and 2), whereas the control group (group 3) returned to baseline. The reduction in migraine days was not significantly different between the groups. Migraine duration and headache index were reduced significantly more in the CSMT than in group 3 towards the end of follow-up. Adverse events were few, mild and transient. Blinding was sustained throughout the RCT. The authors concluded that the effect of CSMT observed in our study is probably due to a placebo response.

One can understand that, for chiropractors, this finding is upsetting. After all, they earn a good part of their living by treating migraineurs. They don’t want to lose patients and, at the same time, they need to claim to practise evidence-based medicine.

What is the way out of this dilemma?

Simple!

They only need to publish a review in which they dilute the irritatingly negative result of the above trial by including all previous low-quality trials with false-positive results and thus generate a new overall finding that alleges CSMT to be evidence-based.

This new systematic review of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) evaluated the evidence regarding spinal manipulation as an alternative or integrative therapy in reducing migraine pain and disability.

The searches identified 6 RCTs eligible for meta-analysis. Intervention duration ranged from 2 to 6 months; outcomes included measures of migraine days (primary outcome), migraine pain/intensity, and migraine disability. Methodological quality varied across the studies. The results showed that spinal manipulation reduced migraine days with an overall small effect size as well as migraine pain/intensity.

The authors concluded that spinal manipulation may be an effective therapeutic technique to reduce migraine days and pain/intensity. However, given the limitations to studies included in this meta-analysis, we consider these results to be preliminary. Methodologically rigorous, large-scale RCTs are warranted to better inform the evidence base for spinal manipulation as a treatment for migraine.

Bob’s your uncle!

Perhaps not perfect, but at least the chiropractic profession can now continue to claim they practice something akin to evidence-based medicine, while happily cashing in on selling their unproven treatments to migraineurs!

But that’s not very fair; research is not for promotion, research is for finding the truth; this white-wash is not in the best interest of patients! I hear you say.

Who cares about fairness, truth or conflicts of interest?

Christine Goertz, one of the review-authors, has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the Director of the Inter‐Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR). Peter M. Wayne, another author, has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the co‐Director of the Inter‐Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR)

And who the Dickens are the NCMIC and the IINCR?

At NCMIC, they believe that supporting the chiropractic profession, including chiropractic research programs and projects, is an important part of our heritage. They also offer business training and malpractice risk management seminars and resources to D.C.s as a complement to the education provided by the chiropractic colleges.

The IINCR is a collaborative effort between PCCR, Yale Center for Medical Informatics and the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. They aim at creating a chiropractic research portfolio that’s truly translational. Vice Chancellor for Research and Health Policy at Palmer College of Chiropractic Christine Goertz, DC, PhD (PCCR) is the network director. Peter Wayne, PhD (Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School) will join Anthony J. Lisi, DC (Yale Center for Medical Informatics and VA Connecticut Healthcare System) as a co-director. These investigators will form a robust foundation to advance chiropractic science, practice and policy. “Our collective efforts provide an unprecedented opportunity to conduct clinical and basic research that advances chiropractic research and evidence-based clinical practice, ultimately benefiting the patients we serve,” said Christine Goertz.

Really: benefiting the patients?

You could have fooled me!

This systematic review was aimed at evaluating the effects of acupuncture on the quality of life of migraineurs. Only randomized controlled trials that were published in Chinese and English were included. In total, 62 trials were included for the final analysis; 50 trials were from China, 3 from Brazil, 3 from Germany, 2 from Italy and the rest came from Iran, Israel, Australia and Sweden.

Acupuncture resulted in lower Visual Analog Scale scores than medication at 1 month after treatment and 1-3 months after treatment. Compared with sham acupuncture, acupuncture resulted in lower Visual Analog Scale scores at 1 month after treatment.

The authors concluded that acupuncture exhibits certain efficacy both in the treatment and prevention of migraines, which is superior to no treatment, sham acupuncture and medication. Further, acupuncture enhanced the quality of life more than did medication.

The authors comment in the discussion section that the overall quality of the evidence for most outcomes was of low to moderate quality. Reasons for diminished quality consist of the following: no mentioned or inadequate allocation concealment, great probability of reporting bias, study heterogeneity, sub-standard sample size, and dropout without analysis.

Further worrisome deficits are that only 14 of the 62 studies reported adverse effects (this means that 48 RCTs violated research ethics!) and that there was a high level of publication bias indicating that negative studies had remained unpublished. However, the most serious concern is the fact that 50 of the 62 trials originated from China, in my view. As I have often pointed out, such studies have to be categorised as highly unreliable.

In view of this multitude of serious problems, I feel that the conclusions of this review must be re-formulated:

Despite the fact that many RCTs have been published, the effect of acupuncture on the quality of life of migraineurs remains unproven.

A new study published in JAMA investigated the long-term effects of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture and being placed in a waiting-list control group for migraine prophylaxis. The trial was a 24-week randomized clinical trial (4 weeks of treatment followed by 20 weeks of follow-up). Participants were randomly assigned to 1) true acupuncture, 2) sham acupuncture, or 3) a waiting-list control group. The trial was conducted from October 2012 to September 2014 in outpatient settings at three clinical sites in China. Participants 18 to 65 years old were enrolled with migraine without aura based on the criteria of the International Headache Society, with migraine occurring 2 to 8 times per month.

Participants in the true acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups received treatment 5 days per week for 4 weeks for a total of 20 sessions. Participants in the waiting-list group did not receive acupuncture but were informed that 20 sessions of acupuncture would be provided free of charge at the end of the trial. Participants used diaries to record migraine attacks. The primary outcome was the change in the frequency of migraine attacks from baseline to week 16. Secondary outcome measures included the migraine days, average headache severity, and medication intake every 4 weeks within 24 weeks.

A total of 249 participants 18 to 65 years old were enrolled, and 245 were included in the intention-to-treat analyses. Baseline characteristics were comparable across the 3 groups. The mean (SD) change in frequency of migraine attacks differed significantly among the 3 groups at 16 weeks after randomization; the mean (SD) frequency of attacks decreased in the true acupuncture group by 3.2 (2.1), in the sham acupuncture group by 2.1 (2.5), and the waiting-list group by 1.4 (2.5); a greater reduction was observed in the true acupuncture than in the sham acupuncture group (difference of 1.1 attacks; 95% CI, 0.4-1.9; P = .002) and in the true acupuncture vs waiting-list group (difference of 1.8 attacks; 95% CI, 1.1-2.5; P < .001). Sham acupuncture was not statistically different from the waiting-list group (difference of 0.7 attacks; 95% CI, −0.1 to 1.4; P = .07).

The authors concluded that among patients with migraine without aura, true acupuncture may be associated with long-term reduction in migraine recurrence compared with sham acupuncture or assigned to a waiting list.

Note the cautious phraseology: “… acupuncture may be associated with long-term reduction …”

The authors were, of course, well advised to be so atypically cautious:

- Comparisons to the waiting list group are meaningless for informing us about the specific effects of acupuncture, as they fail to control for placebo-effects.

- Comparisons between real and sham acupuncture must be taken with a sizable pinch of salt, as the study was not therapist-blind and the acupuncturists may easily have influenced their patients in various ways to report the desired result (the success of patient-blinding was not reported but would have gone some way to solving this problem).

- The effect size of the benefit is tiny and of doubtful clinical relevance.

My biggest concern, however, is the fact that the study originates from China, a country where virtually 100% of all acupuncture studies produce positive (or should that be ‘false-positive’?) findings and data fabrication has been reported to be rife. These facts do not inspire trustworthiness, in my view.

So, does acupuncture work for migraine? The current Cochrane review included 22 studies and its authors concluded that the available evidence suggests that adding acupuncture to symptomatic treatment of attacks reduces the frequency of headaches. Contrary to the previous findings, the updated evidence also suggests that there is an effect over sham, but this effect is small. The available trials also suggest that acupuncture may be at least similarly effective as treatment with prophylactic drugs. Acupuncture can be considered a treatment option for patients willing to undergo this treatment. As for other migraine treatments, long-term studies, more than one year in duration, are lacking.

So, maybe acupuncture is effective. Personally, I am not convinced and certainly do not think that the new JAMA study significantly strengthened the evidence.

A new study tested the efficacy of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (CSMT) for migraine. It was designed as a three-armed, single-blinded, placebo -controlled RCT of 17 months duration including 104 migraineurs with at least one migraine attack per month. Active treatment consisted of CSMT (group 1) and the placebo was a sham push manoeuvre of the lateral edge of the scapula and/or the gluteal region (group 2). The control group continued their usual pharmacological management (group 3).

The RCT began with a one-month run-in followed by three months intervention. The outcome measures were quantified at the end of the intervention and at 3, 6 and 12 months of follow-up. The primary end-point was the number of migraine days per month. Secondary end-points were migraine duration, migraine intensity and headache index, and medicine consumption.

The results show that migraine days were significantly reduced within all three groups from baseline to post-treatment (P < 0.001). The effect continued in the CSMT and placebo groups at all follow-up time points (groups 1 and 2), whereas the control group (group 3) returned to baseline. The reduction in migraine days was not significantly different between the groups. Migraine duration and headache index were reduced significantly more in the CSMT than in group 3 towards the end of follow-up. Adverse events were few, mild and transient. Blinding was strongly sustained throughout the RCT.

The authors concluded that it is possible to conduct a manual-therapy RCT with concealed placebo. The effect of CSMT observed in our study is probably due to a placebo response.

Chiropractors often cite clinical trials which suggest that CSMT might be effective. The effects sizes are rarely impressive, and it is tempting to suspect that the outcomes are mostly due to bias. Chiropractors, of course, deny such an explanation. Yet, to me, it seems fairly obvious: trials of CSMT are not blind, and therefore the expectation of the patient is likely to have major influence on the outcome.

Because of this phenomenon (and several others, of course), sceptics are usually unconvinced of the value of chiropractic. Chiropractors often respond by claiming that blind studies of physical intervention such as CSMT are not possible. This, however, is clearly not true; there have been several trials that employed sham treatments which adequately mimic CSMT. As these frequently fail to show what chiropractors had hoped, the methodology is intensely disliked by chiropractors.

The above study is yet another trial that adequately controls for patients’ expectation, and it shows that the apparent efficacy of CSMT disappears when this source of bias is properly accounted for. To me, such findings make a lot of sense, and I suspect that most, if not all the ‘positive’ studies of CSMT would turn out to be false positive, once such residual bias is eliminated.