methodology

On Twitter and elsewhere, homeopaths have been celebrating: FINALLY A PROOF OF HOMEOPATHY HAS BEEN PUBLISHED IN A TOP SCIENCE JOURNAL!!!

Here is just one example:

#homeopathy under threat because of lack of peer reviewed studies in respectable journals? Think again. Study published in the most prestigious journal Nature shows efficacy of rhus tox in pain control in rats.

But what exactly does this study show (btw, it was not published in ‘Nature’)?

The authors of the paper in question evaluated antinociceptive efficacy of Rhus Tox in the neuropathic pain and delineated its underlying mechanism. Initially, in-vitro assay using LPS-mediated ROS-induced U-87 glioblastoma cells was performed to study the effect of Rhus Tox on reactive oxygen species (ROS), anti-oxidant status and cytokine profile. Rhus Tox decreased oxidative stress and cytokine release with restoration of anti-oxidant systems. Chronic treatment with Rhus Tox ultra dilutions for 14 days ameliorated neuropathic pain revealed as inhibition of cold, warm and mechanical allodynia along with improved motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV) in constricted nerve. Rhus Tox decreased the oxidative and nitrosative stress by reducing malondialdehyde (MDA) and nitric oxide (NO) content, respectively along with up regulated glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase activity in sciatic nerve of rats. Notably, Rhus Tox treatment caused significant reductions in the levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) as compared with CCI-control group. Protective effect of Rhus Tox against CCI-induced sciatic nerve injury in histopathology study was exhibited through maintenance of normal nerve architecture and inhibition of inflammatory changes. Overall, neuroprotective effect of Rhus Tox in CCI-induced neuropathic pain suggests the involvement of anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

END OF QUOTE

I am utterly under-whelmed by in-vitro experiments (which are prone to artefacts) and animal studies (especially those with a sample size of 8!) of homeopathy. I think they have very little relevance to the question whether homeopathy works.

But there is more, much more!

It has been pointed out that there are several oddities in this paper which are highly suspicious of scientific misconduct or fraud. It has been noted that the study used duplicated data figures that claimed to show different experimental results, inconsistently reported data and results for various treatment dilutions in the text and figures, contained suspiciously identical data points throughout a series of figures that were reported to represent different experimental results, and hinged on subjective, non-blinded data from a pain experiment involving just eight rats.

Lastly, others pointed out that even if the data is somehow accurate, the experiment is unconvincing. The fast timing differences of paw withdraw is subjective. It’s also prone to bias because the researchers were not blinded to the rats’ treatments (meaning they could have known which animals were given the control drug or the homeopathic dilution). Moreover, eight animals in each group is not a large enough number from which to draw firm conclusions, they argue.

As one consequence of these suspicions, the journal has recently added the following footnote to the publication:

10/1/2018 Editors’ Note: Readers are alerted that the conclusions of this paper are subject to criticisms that are being considered by the editors. Appropriate editorial action will be taken once this matter is resolved.

WATCH THIS SPACE!

Aromatherapy usually involves the application of diluted essential (volatile) oils via a gentle massage of the body surface. The chemist Rene-Maurice Gattefosse (1881-1950) coined the term ‘aromatherapy’ after experiencing that lavender oil helped to cure a severe burn of his hand. In 1937, he published a book on the subject: Aromathérapie: Les Huiles Essentielles, Hormones Végétales. Later, the French surgeon Jean Valnet used essential oils to help heal soldiers’ wounds in World War II.

Aromatherapy is currently one of the most popular of all alternative therapies. The reason for its popularity seems simple: it is an agreeable, luxurious form of pampering. Whether it truly merits to be called a therapy is debatable.

The authors of this systematic review stated that they wanted to critically assess the effect of aromatherapy on the psychological symptoms as noted in the postmenopausal and elderly women. They conducted electronic literature searches and fount 4 trials that met their inclusion criteria. The findings demonstrated that aromatherapy massage significantly improves psychological symptoms in menopausal, elderly women as compared to controls. In one trial, aromatherapy massage was no more effective than the untreated group regarding their experience of symptoms such as nervousness.

The authors concluded that aromatherapy may be beneficial in attenuating the psychological symptoms that these women may experience, such as anxiety and depression, but it is not considered as an effective treatment to manage nervousness symptom among menopausal women. This finding should be observed in light of study limitations.

In the discussion section, the authors state that to the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis evaluating the effect of aromatherapy on the psychological symptoms. I believe that they might be mistaken. Here are two of my own papers (other researchers have published further reviews) on the subject:

- Aromatherapy is the therapeutic use of essential oil from herbs, flowers, and other plants. The aim of this overview was to provide an overview of systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of aromatherapy. We searched 12 electronic databases and our departmental files without restrictions of time or language. The methodological quality of all systematic reviews was evaluated independently by two authors. Of 201 potentially relevant publications, 10 met our inclusion criteria. Most of the systematic reviews were of poor methodological quality. The clinical subject areas were hypertension, depression, anxiety, pain relief, and dementia. For none of the conditions was the evidence convincing. Several SRs of aromatherapy have recently been published. Due to a number of caveats, the evidence is not sufficiently convincing that aromatherapy is an effective therapy for any condition.

- Aromatherapy is becoming increasingly popular; however there are few clear indications for its use. To systematically review the literature on aromatherapy in order to discover whether any clinical indication may be recommended for its use, computerised literature searches were performed to retrieve all randomised controlled trials of aromatherapy from the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, British Nursing Index, CISCOM, and AMED. The methodological quality of the trials was assessed using the Jadad score. All trials were evaluated independently by both authors and data were extracted in a pre-defined, standardised fashion. Twelve trials were located: six of them had no independent replication; six related to the relaxing effects of aromatherapy combined with massage. These studies suggest that aromatherapy massage has a mild, transient anxiolytic effect. Based on a critical assessment of the six studies relating to relaxation, the effects of aromatherapy are probably not strong enough for it to be considered for the treatment of anxiety. The hypothesis that it is effective for any other indication is not supported by the findings of rigorous clinical trials.

Omitting previous research may be odd, but it is not a fatal flaw. What makes this review truly dismal is the fact that the authors fail to discuss the poor quality of the primary studies. They are of such deplorable rigor that one can really not draw any conclusion at all from them. I therefore find the conclusions of this new paper unacceptable and think that our statement (even though a few years old) is much more accurate: the evidence is not sufficiently convincing that aromatherapy is an effective therapy for any condition.

Evening primrose oil (EPO) is amongst the best-selling herbal remedies of all times. It is marketed in most countries as a dietary supplement. It is being promoted for eczema, rheumatoid arthritis, premenstrual syndrome, breast pain, menopause symptoms, and many other conditions. EPO seems to be a prime example for the fact that, in alternative medicine, the commercial success of a remedy is not necessarily determined by the strength of the evidence but by the intensity and cleverness of the marketing activities.

Evening primrose oil has been extensively tested in clinical trials for a wide range of conditions, including eczema (atopic dermatitis), postmenopausal symptoms, asthma, psoriasis, cellulite, hyperactivity, multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, obesity, chronic fatigue syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and mastalgia. As I have reported previously, these data were burdened with mischief and scientific misconduct, and it is therefore not easy to differentiate between science, pseudoscience and fraud. The results of the more reliable investigations fail to show that it is effective for any condition. A Cochrane review of 2013, for instance, concluded that supplements of evening primrose oil lack effect on eczema; improvement was similar to respective placebos used in trials.

But now, a new study has emerged that casts doubt on this conclusion. The aim of this double-blinded, placebo-controlled RCT is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EPO in Korean patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).

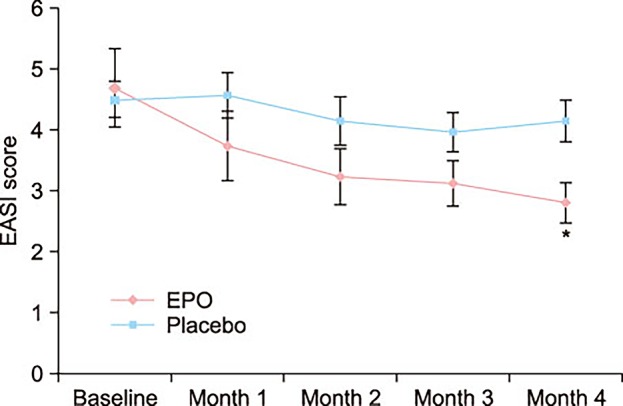

Fifty mild AD patients with an Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) score of 10 or less were randomly divided into two groups. The first group received an oval unmarked capsule containing 450 mg of EPO (40 mg of GLA) per capsule, while placebo capsules identical in appearance and containing 450 mg of soybean oil were given to the other group. Treatment continued for a period of 4 months. EASI scores, transepidermal water loss (TEWL), and skin hydration were evaluated in all the AD patients at the baseline, and in months 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the study.

At the end of month 4, the patients of the EPO group showed a significant improvement in the EASI score, whereas the patients of the placebo group did not. There was a significant difference in the EASI score between the EPO and placebo groups. Although not statistically significant, the TEWL and skin hydration also slightly improved in the EPO patients group. Adverse effect were not found in neither the experimental group nor the control group during the study period.

The authors concluded by suggesting that EPO is a safe and effective medicine for Korean patients with mild AD.

I find this study odd for several reasons:

- One cannot possibly draw conclusions based on such a small sample.

- The authors state that a total of 69 mild AD patients were enrolled and randomized into either the control group (14 males and 17 females) or the EPO group (20 males and 18 females). Six patients in the control group and 13 patients in the EPO group dropped out due to follow up loss. No patient dropped out because the disease worsened. Should this not have necessitated an intention-to-treat analysis? And, if 19 patients were lost to follow-up, how do the authors know that their disease did not worsen?

- The graph shows impressively the lack of a placebo-response. I don’t understand why there was none.

- The authors state that there were no adverse effects at all. I find this implausible; we know that even taking placebos will prompt patients to report adverse effects.

So, what to make out of this?

I am not at all sure, but one thing is certain: this study does not alter my verdict on EPO; as far as I am concerned, the effectiveness of EPO for AD is unproven.

The aim of this RCT was to investigate the effects of an osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) which includes a diaphragm intervention compared to the same OMT with a sham diaphragm intervention in chronic non-specific low back pain (NS-CLBP).

Participants (N=66) with a diagnosis of NS-CLBP lasting at least 3 months were randomized to receive either an OMT protocol including specific diaphragm techniques (n=33) or the same OMT protocol with a sham diaphragm intervention (n=33), conducted in 5 sessions provided during 4 weeks.

The primary outcomes were pain (evaluated with the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire [SF-MPQ] and the visual analog scale [VAS]) and disability (assessed with the Roland-Morris Questionnaire [RMQ] and the Oswestry Disability Index [ODI]). Secondary outcomes were fear-avoidance beliefs, level of anxiety and depression, and pain catastrophization. All outcome measures were evaluated at baseline, at week 4, and at week 12.

A statistically significant reduction was observed in the experimental group compared to the sham group in all variables assessed at week 4 and at week 12. Moreover, improvements in pain and disability were clinically relevant.

The authors concluded that an OMT protocol that includes diaphragm techniques produces significant and clinically relevant improvements in pain and disability in patients with NS-CLBP compared to the same OMT protocol using sham diaphragm techniques.

This seems to be a rigorous study. The authors describe in detail their well-standardised interventions in the full text of their paper. This, of course, will be essential, if someone wants to repeat the trial.

I have but a few points to add:

- What I fail to understand is this: why the authors call the interventions osteopathic? The therapist was a physiotherapist and the techniques employed are, if I am not mistaken, as much physiotherapeutic as osteopathic.

- The findings of this trial are encouraging but almost seem a little too good to be true. They need, of course, to be independently replicated in a larger study.

- If that is done, I would suggest to check whether the blinding of the patient was successful. If not, there is a suspicion that the diaphragm technique works partly or mostly via a placebo effect.

- I would also try to make sure that the therapist cannot influence the results in any way, for instance, by verbal or non-verbal suggestions.

- Finally, I suggest to employ more than one therapist to increase generalisability.

Once all these hurdles are taken, we might indeed have made some significant progress in the manual therapy of NS-CLBP.

Fish oil (omega-3 PUFA) preparations are today extremely popular and amongst the best-researched dietary supplement. During the 1970s, two Danish scientists, Bang and Dyerberg, remarked that Greenland Eskimos had a baffling lower prevalence of coronary artery disease than mainland Danes. They also noted that their diet contained large amounts of seal and whale blubber and suggested that this ‘Eskimo-diet’ was a key factor in the lower prevalence. Subsequently, a flurry of research stared to investigate the phenomenon, and it was shown that the ‘Eskimo-diet’ contained unusually high concentrations of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from fish oils (seals and whales feed predominantly on fish).

Initial research also demonstrated that the regular consumption of fish oil has a multitude of cardiovascular and anti-inflammatory effects. This led to the promotion of fish oil supplements for a wide range of conditions. Meanwhile, many of these encouraging findings have been overturned by more rigorous studies, and the enthusiasm for fish oil supplements has somewhat waned. But now, a new paper has come out with surprising findings.

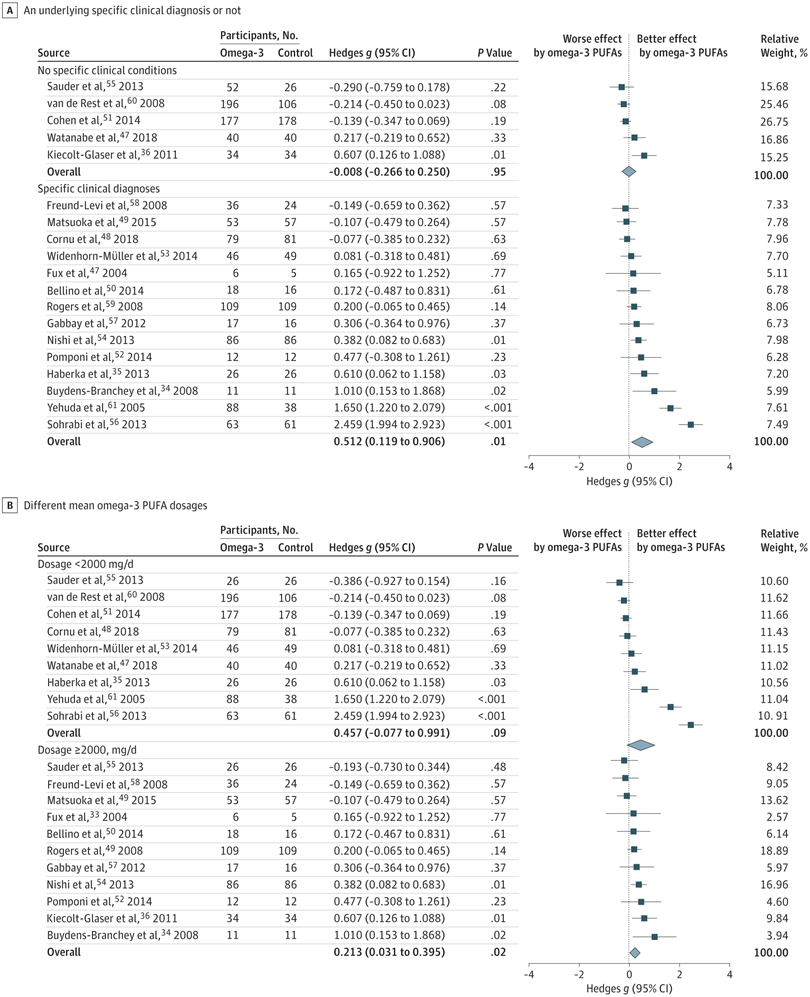

The objective of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the association of anxiety symptoms with omega-3 PUFA treatment compared with controls in varied populations.

A search was performed of clinical trials assessing the anxiolytic effect of omega-3 PUFAs in humans, in either placebo-controlled or non–placebo-controlled designs. Of 104 selected articles, 19 entered the final data extraction stage. Two authors independently extracted the data according to a predetermined list of interests. A random-effects model meta-analysis was performed. Changes in the severity of anxiety symptoms after omega-3 PUFA treatment served as the main endpoint.

In total, 1203 participants with omega-3 PUFA treatment and 1037 participants without omega-3 PUFA treatment showed an association between clinical anxiety symptoms among participants with omega-3 PUFA treatment compared with control arms. Subgroup analysis showed that the association of treatment with reduced anxiety symptoms was significantly greater in subgroups with specific clinical diagnoses than in subgroups without clinical conditions. The anxiolytic effect of omega-3 PUFAs was significantly better than that of controls only in subgroups with a higher dosage (at least 2000 mg/d) and not in subgroups with a lower dosage (<2000 mg/d).

The authors concluded that this review indicates that omega-3 PUFAs might help to reduce the symptoms of clinical anxiety. Further well-designed studies are needed in populations in whom anxiety is the main symptom.

I think this is a fine meta-analysis reporting clear results. I doubt that this paper truly falls under the umbrella of alternative medicine, but fish oil is a popular food supplement and should be mentioned on this blog. Of course, the average effect size is modest, but the findings are nevertheless intriguing.

Proof of Principle or Concept studies are investigations usually for an early stage of clinical drug development when a compound has shown potential in animal models and early safety testing. This step often links between Phase-I and dose ranging Phase-II studies. These small-scale studies are designed to detect a signal that the drug is active on a patho-physiologically relevant mechanism, as well as preliminary evidence of efficacy in a clinically relevant endpoint.

For therapies that have been in use for many years, proof of concept studies are unusual to say the least. A proof of concept study of osteopathy has never been heard of. This is why I was fascinated by this new paper. The objective of this ‘proof of concept’ study was to evaluate the effect of osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMTh) on chronic symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Patients (n=22) with MS received 5 forty-minute MS health education sessions (control group) or 5 OMTh sessions (OMTh group). All participants completed a questionnaire that assessed their level of clinical disability, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and quality of life before the first session, one week after the final session, and 6 months after the final session. The Extended Disability Status Scale, a modified Fatigue Impact Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory-II, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the 12-item Short Form Health Survey were used to assess clinical disability, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and quality of life, respectively. In the OMTh group, statistically significant improvements in fatigue and depression were found one week after the final session. A non-significant increase in quality of life was also found in the OMTh group one week after the final session.

The authors concluded that the results demonstrate that OMTh should be considered in the treatment of patients with chronic symptoms of MS.

Who said that reading alternative medicine research papers is not funny? I for one laughed heartily when I read this (no need at all to go into the many obvious flaws of the study). Calling a pilot study ‘proof of concept’ is certainly not without hilarity. Drawing definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of OMTh is outright laughable. But issuing a far-reaching recommendation for use of OMTh in MS is just better than the best comedy. This had me in stiches!

I congratulate the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association and the international team of authors for providing us with such fun.

Osteopathy is a form of manual therapy invented by the American Andrew Taylor Still (1828-1917). Today, US osteopaths (doctors of osteopathy or DOs) practise no or little manual therapy; they are fully recognised as medical doctors who can specialise in any medical field after their training which is almost identical with that of MDs. Outside the US, osteopaths practice almost exclusively manual treatments and are considered alternative practitioners. This post deals with the latter category of osteopaths.

Still defined his original osteopathy as a science which consists of such exact, exhaustive, and verifiable knowledge of the structure and function of the human mechanism, anatomical, physiological and psychological, including the chemistry and physics of its known elements, as has made discoverable certain organic laws and remedial resources, within the body itself, by which nature under the scientific treatment peculiar to osteopathic practice, apart from all ordinary methods of extraneous, artificial, or medicinal stimulation, and in harmonious accord with its own mechanical principles, molecular activities, and metabolic processes, may recover from displacements, disorganizations, derangements, and consequent disease, and regained its normal equilibrium of form and function in health and strength.

Based on such vague and largely nonsensical statements, traditional osteopaths feel entitled to offer treatments for most human diseases, conditions and symptoms. The studies they produce to back up their claims tend to be as poor as Still’s original assumptions were fantastic.

Here is an apt example:

The aim of this new study was to study the effect of osteopathic manipulation on pain relief and quality of life improvement in hospitalized oncology geriatric patients.

The researchers conducted a non-randomized controlled clinical trial with 23 cancer patients. They were allocated to two groups: the study group (OMT [osteopathic manipulative therapy] group, N = 12) underwent OMT in addition to physiotherapy (PT), while the control group (PT group, N = 12) underwent only PT. Included were postsurgical cancer patients, male and female, age ⩾65 years, with an oncology prognosis of 6 to 24 months and chronic pain for at least 3 months with an intensity score higher than 3, measured with the Numeric Rating Scale. Exclusion criteria were patients receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment at the time of the study, with mental disorders (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] = 10-20), with infection, anticoagulation therapy, cardiopulmonary disease, or clinical instability post-surgery. Oncology patients were admitted for rehabilitation after cancer surgery. The main cancers were colorectal cancer, osteosarcoma, spinal metastasis from breast and prostatic cancer, and kidney cancer.

The OMT, based on osteopathic principles of body unit, structure-function relationship, and homeostasis, was designed for each patient on the basis of the results of the osteopathic examination. Diagnosis and treatment were founded on 5 models: biomechanics, neurologic, metabolic, respiratory-circulatory, and behaviour. The OMT protocol was administered by an osteopath with clinical experience of 10 years in one-on-one individual sessions. The techniques used were: dorsal and lumbar soft tissue, rib raising, back and abdominal myofascial release, cervical spine soft tissue, sub-occipital decompression, and sacroiliac myofascial release. Back and abdominal myofascial release techniques are used to improve back movement and internal abdominal pressure. Sub-occipital decompression involves traction at the base of the skull, which is considered to release restrictions around the vagus nerve, theoretically improving nerve function. Sacroiliac myofascial release is used to improve sacroiliac joint movement and to reduce ligament tension. Strain-counter-strain and muscle energy technique are used to diminish the presence of trigger points and their pain intensity. OMT was repeated once every week during 4 weeks for each group, for a total of 4 treatments. Each treatment lasted 45 minutes.

At enrolment (T0), the patients were evaluated for pain intensity and quality of life by an external examiner. All patients were re-evaluated every week (T1, T2, T3, and T4) for pain intensity, and at the end of the study treatment (T4) for quality of life.

The OMT added to physiotherapy produced a significant reduction in pain both at T2 and T4. The difference in quality of life improvements between T0 and T4 was not statistically significant. Pain improved in the PT group at T4. Between-group analysis of pain and quality of life did not show any significant difference between the two treatments.

The authors concluded that our study showed a significant improvement in pain relief and a nonsignificant improvement in quality of life in hospitalized geriatric oncology patients during osteopathic manipulative treatment.

GOOD GRIEF!

Where to begin?

Even if there had been a difference in outcome between the two groups, such a finding would not have shown an effect of OMT per se. More likely, it would have been due to the extra attention and the expectation in the OMT group (or caused by the lack of randomisation). The A+B vs B design used for this study does not control for non-specific effects. Therefore it is incapable of establishing a causal relationship between the therapy and the outcome.

As it turns out, there were no inter-group differences. How can this be? I have often stated that A+B is always more than B alone. And this is surely true!

So, how can I explain this?

As far as I can see, there are two possibilities:

- The study was underpowered, and thus an existing difference was not picked up.

- The OMT had a detrimental effect on the outcome measures thus neutralising the positive effects of the extra attention and expectation.

And which possibility does apply in this case?

Nobody can know from these data.

Integrative Cancer Therapies, the journal that published this paper, states that it focuses on a new and growing movement in cancer treatment. The journal emphasizes scientific understanding of alternative and traditional medicine therapies, and the responsible integration of both with conventional health care. Integrative care includes therapeutic interventions in diet, lifestyle, exercise, stress care, and nutritional supplements, as well as experimental vaccines, chrono-chemotherapy, and other advanced treatments. I feel that the editors should rather focus more on the quality of the science they publish.

My conclusion from all this is the one I draw so depressingly often: fatally flawed science is not just useless, it is unethical, gives clinical research a bad name, hinders progress, and can be harmful to patients.

I remember reading this paper entitled ‘Comparison of acupuncture and other drugs for chronic constipation: A network meta-analysis’ when it first came out. I considered discussing it on my blog, but then decided against it for a range of reasons which I shall explain below. The abstract of the original meta-analysis is copied below:

The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and side effects of acupuncture, sham acupuncture and drugs in the treatment of chronic constipation. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of acupuncture and drugs for chronic constipation were comprehensively retrieved from electronic databases (such as PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, CNKI, Wanfang Database, VIP Database and CBM) up to December 2017. Additional references were obtained from review articles. With quality evaluations and data extraction, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was performed using a random-effects model under a frequentist framework. A total of 40 studies (n = 11032) were included: 39 were high-quality studies and 1 was a low-quality study. NMA showed that (1) acupuncture improved the symptoms of chronic constipation more effectively than drugs; (2) the ranking of treatments in terms of efficacy in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome was acupuncture, polyethylene glycol, lactulose, linaclotide, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, prucalopride, sham acupuncture, tegaserod, and placebo; (3) the ranking of side effects were as follows: lactulose, lubiprostone, bisacodyl, polyethylene glycol, prucalopride, linaclotide, placebo and tegaserod; and (4) the most commonly used acupuncture point for chronic constipation was ST25. Acupuncture is more effective than drugs in improving chronic constipation and has the least side effects. In the future, large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to prove this. Sham acupuncture may have curative effects that are greater than the placebo effect. In the future, it is necessary to perform high-quality studies to support this finding. Polyethylene glycol also has acceptable curative effects with fewer side effects than other drugs.

END OF 1st QUOTE

This meta-analysis has now been retracted. Here is what the journal editors have to say about the retraction:

After publication of this article [1], concerns were raised about the scientific validity of the meta-analysis and whether it provided a rigorous and accurate assessment of published clinical studies on the efficacy of acupuncture or drug-based interventions for improving chronic constipation. The PLOS ONE Editors re-assessed the article in collaboration with a member of our Editorial Board and noted several concerns including the following:

- Acupuncture and related terms are not mentioned in the literature search terms, there are no listed inclusion or exclusion criteria related to acupuncture, and the outcome measures were not clearly defined in terms of reproducible clinical measures.

- The study included acupuncture and electroacupuncture studies, though this was not clearly discussed or reported in the Title, Methods, or Results.

- In the “Routine paired meta-analysis” section, both acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups were reported as showing improvement in symptoms compared with placebo. This finding and its implications for the conclusions of the article were not discussed clearly.

- Several included studies did not meet the reported inclusion criteria requiring that studies use adult participants and assess treatments of >2 weeks in duration.

- Data extraction errors were identified by comparing the dataset used in the meta-analysis (S1 Table) with details reported in the original research articles. Errors included aspects of the study design such as the experimental groups included in the study, the number of study arms in the trial, number of participants, and treatment duration. There are also several errors in the Reference list.

- With regard to side effects, 22 out of 40 studies were noted as having reported side effects. It was not made clear whether side effects were assessed as outcome measures for the other 18 studies, i.e. did the authors collect data clarifying that there were no side effects or was this outcome measure not assessed or reported in the original article. Without this clarification the conclusion comparing side effect frequencies is not well supported.

- The network geometry presented in Fig 5 is not correct and misrepresents some of the study designs, for example showing two-arm studies as three-arm studies.

- The overall results of the meta-analysis are strongly reliant on the evidence comparing acupuncture versus lactulose treatment. Several of the trials that assessed this comparison were poorly reported, and the meta-analysis dataset pertaining to these trials contained data extraction errors. Furthermore, potential bias in studies assessing lactulose efficacy in acupuncture trials versus lactulose efficacy in other trials was not sufficiently addressed.

While some of the above issues could be addressed with additional clarifications and corrections to the text, the concerns about study inclusion, the accuracy with which the primary studies’ research designs and data were represented in the meta-analysis, and the reporting quality of included studies directly impact the validity and accuracy of the dataset underlying the meta-analysis. As a consequence, we consider that the overall conclusions of the study are not reliable. In light of these issues, the PLOS ONE Editors retract the article. We apologize that these issues were not adequately addressed during pre-publication peer review.

LZ disagreed with the retraction. YM and XD did not respond.

END OF 2nd QUOTE

Let me start by explaining why I initially decided not to discuss this paper on my blog. Already the first sentence of the abstract put me off, and an entire chorus of alarm-bells started ringing once I read further.

- A meta-analysis is not a ‘study’ in my book, and I am somewhat weary of researchers who employ odd or unprecise language.

- We all know (and I have discussed it repeatedly) that studies of acupuncture frequently fail to report adverse effects (in doing this, their authors violate research ethics!). So, how can it be a credible aim of a meta-analysis to compare side-effects in the absence of adequate reporting?

- The methodology of a network meta-analysis is complex and I know not a lot about it.

- Several things seemed ‘too good to be true’, for instance, the funnel-plot and the overall finding that acupuncture is the best of all therapeutic options.

- Looking at the references, I quickly confirmed my suspicion that most of the primary studies were in Chinese.

In retrospect, I am glad I did not tackle the task of criticising this paper; I would probably have made not nearly such a good job of it as PLOS ONE eventually did. But it was only after someone raised concerns that the paper was re-reviewed and all the defects outlined above came to light.

While some of my concerns listed above may have been trivial, my last point is the one that troubles me a lot. As it also related to dozens of Cochrane reviews which currently come out of China, it is worth our attention, I think. The problem, as I see it, is as follows:

- Chinese (acupuncture, TCM and perhaps also other) trials are almost invariably reporting positive findings, as we have discussed ad nauseam on this blog.

- Data fabrication seems to be rife in China.

- This means that there is good reason to be suspicious of such trials.

- Many of the reviews that currently flood the literature are based predominantly on primary studies published in Chinese.

- Unless one is able to read Chinese, there is no way of evaluating these papers.

- Therefore reviewers of journal submissions tend to rely on what the Chinese review authors write about the primary studies.

- As data fabrication seems to be rife in China, this trust might often not be justified.

- At the same time, Chinese researchers are VERY keen to publish in top Western journals (this is considered a great boost to their career).

- The consequence of all this is that reviews of this nature might be misleading, even if they are published in top journals.

I have been struggling with this problem for many years and have tried my best to alert people to it. However, it does not seem that my efforts had even the slightest success. The stream of such reviews has only increased and is now a true worry (at least for me). My suspicion – and I stress that it is merely that – is that, if one would rigorously re-evaluate these reviews, their majority would need to be retracted just as the above paper. That would mean that hundreds of papers would disappear because they are misleading, a thought that should give everyone interested in reliable evidence sleepless nights!

So, what can be done?

Personally, I now distrust all of these papers, but I admit, that is not a good, constructive solution. It would be better if Journal editors (including, of course, those at the Cochrane Collaboration) would allocate such submissions to reviewers who:

- are demonstrably able to conduct a CRITICAL analysis of the paper in question,

- can read Chinese,

- have no conflicts of interest.

In the case of an acupuncture review, this would narrow it down to perhaps just a handful of experts worldwide. This probably means that my suggestion is simply not feasible.

But what other choice do we have?

One could oblige the authors of all submissions to include full and authorised English translations of non-English articles. I think this might work, but it is, of course, tedious and expensive. In view of the size of the problem (I estimate that there must be around 1 000 reviews out there to which the problem applies), I do not see a better solution.

(I would truly be thankful, if someone had a better one and would tell us)

Psoriasis is one of those conditions that is

- chronic,

- not curable,

- irritating to the point where it reduces quality of life.

In other words, it is a disease for which virtually all alternative treatments on the planet are claimed to be effective. But which therapies do demonstrably alleviate the symptoms?

This review (published in JAMA Dermatology) compiled the evidence on the efficacy of the most studied complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities for treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis and discusses those therapies with the most robust available evidence.

PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov searches (1950-2017) were used to identify all documented CAM psoriasis interventions in the literature. The criteria were further refined to focus on those treatments identified in the first step that had the highest level of evidence for plaque psoriasis with more than one randomized clinical trial (RCT) supporting their use. This excluded therapies lacking RCT data or showing consistent inefficacy.

A total of 457 articles were found, of which 107 articles were retrieved for closer examination. Of those articles, 54 were excluded because the CAM therapy did not have more than 1 RCT on the subject or showed consistent lack of efficacy. An additional 7 articles were found using references of the included studies, resulting in a total of 44 RCTs (17 double-blind, 13 single-blind, and 14 nonblind), 10 uncontrolled trials, 2 open-label nonrandomized controlled trials, 1 prospective controlled trial, and 3 meta-analyses.

Compared with placebo, application of topical indigo naturalis, studied in 5 RCTs with 215 participants, showed significant improvements in the treatment of psoriasis. Treatment with curcumin, examined in 3 RCTs (with a total of 118 participants), 1 nonrandomized controlled study, and 1 uncontrolled study, conferred statistically and clinically significant improvements in psoriasis plaques. Fish oil treatment was evaluated in 20 studies (12 RCTs, 1 open-label nonrandomized controlled trial, and 7 uncontrolled studies); most of the RCTs showed no significant improvement in psoriasis, whereas most of the uncontrolled studies showed benefit when fish oil was used daily. Meditation and guided imagery therapies were studied in 3 single-blind RCTs (with a total of 112 patients) and showed modest efficacy in treatment of psoriasis. One meta-analysis of 13 RCTs examined the association of acupuncture with improvement in psoriasis and showed significant improvement with acupuncture compared with placebo.

The authors concluded that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis are indigo naturalis, curcumin, dietary modification, fish oil, meditation, and acupuncture. This review will aid practitioners in advising patients seeking unconventional approaches for treatment of psoriasis.

I am sorry to say so, but this review smells fishy! And not just because of the fish oil. But the fish oil data are a good case in point: the authors found 12 RCTs of fish oil. These details are provided by the review authors in relation to oral fish oil trials: Two double-blind RCTs (one of which evaluated EPA, 1.8g, and DHA, 1.2g, consumed daily for 12 weeks, and the other evaluated EPA, 3.6g, and DHA, 2.4g, consumed daily for 15 weeks) found evidence supporting the use of oral fish oil. One open-label RCT and 1 open-label non-randomized controlled trial also showed statistically significant benefit. Seven other RCTs found lack of efficacy for daily EPA (216mgto5.4g)or DHA (132mgto3.6g) treatment. The remainder of the data supporting efficacy of oral fish oil treatment were based on uncontrolled trials, of which 6 of the 7 studies found significant benefit of oral fish oil. This seems to support their conclusion. However, the authors also state that fish oil was not shown to be effective at several examined doses and duration. Confused? Yes, me too!

Even more confusing is their failure to mention a single trial of Mahonia aquifolium. A 2013 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Dermatology included 5 RCTs of Mahonia aquifolium which, according to these authors, provided ‘limited support’ for its effectiveness. How could they miss that?

More importantly, how could the reviewers miss to conduct a proper evaluation of the quality of the studies they included in their review (even in their abstract, they twice speak of ‘robust evidence’ – but how can they without assessing its robustness? [quantity is not remotely the same as quality!!!]). Without a transparent evaluation of the rigour of the primary studies, any review is nearly worthless.

Take the 12 acupuncture trials, for instance, which the review authors included based not on an assessment of the studies but on a dodgy review published in a dodgy journal. Had they critically assessed the quality of the primary studies, they could have not stated that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis …[include]… acupuncture. Instead they would have had to admit that these studies are too dubious for any firm conclusion. Had they even bothered to read them, they would have found that many are in Chinese (which would have meant they had to be excluded in their review [as many pseudo-systematic reviewers, the authors only considered English papers]).

There might be a lesson in all this – well, actually I can think of at least two:

- Systematic reviews might well be the ‘Rolls Royce’ of clinical evidence. But even a Rolls Royce needs to be assembled correctly, otherwise it is just a heap of useless material.

- Even top journals do occasionally publish poor-quality and thus misleading reviews.

Medline is the biggest electronic databank for articles published in medicine and related fields. It is therefore the most important source of information in this area. I use it regularly to monitor what new papers have been published in the various fields of alternative medicine.

As the number of Medline-listed papers dated 2018 on homeopathy has just reached 100, I thought it might be the moment to run a quick analysis on this material. The first thing to note is that it took until August for 100 articles dated 2018 to emerge. To explain how embarrassing this is, we need a few comparative figures. At the same moment (6/9/18), we have, for instance:

- 126576 articles for surgery

- 5001 articles or physiotherapy

- 30215 articles for psychiatry

- 60161 articles for pharmacology

Even compared to other types of alternative medicine, homeopathy is being dwarfed. Currently the figures are, for instance:

- 2232 for herbal medicine

- 1949 for dietary supplements

- 1222 for acupuncture

This does not look as though homeopathy is a frightfully active area of research, if I may say so. Looking at the type of articles (yes, I did look at all the 100 papers and categorised them the best I could) published in homeopathy, things get even worse:

- 29 were comments, letters, editorials, etc.

- 16 were basic and pre-clinical papers,

- 12 were non-systematic reviews,

- 10 were surveys,

- 7 were case-reports,

- 5 were pilot or feasibility studies,

- 5 were systematic reviews,

- 5 were controlled clinical trials,

- 2 were case series,

- the rest of the articles was not on homeopathy at all.

I find this pretty depressing. Most of the 100 papers turn out to be no real research at all. Crucial topics are not being covered. There was, for example, not a single paper on the risks of homeopathy (no, don’t tell me it is harmless; it can and does regularly cost the lives of patients who trust the bogus claims of homeopaths). There was no article investigating the important question whether the practice of homeopathy does not violate the rules of medical ethics (think of informed consent or the imperative to do more harm than good). And a mere 5 clinical trials is just a dismal amount, in my view.

In a previous post, I have already shown that, in 2015, homeopathy research was deplorable. My new analysis suggests that the situation has become much worse. One might even go as far as asking whether 2018 might turn out to be the year when homeopathy research finally died a natural death.

PROGRESS AT LAST!!!