methodology

Cupping is a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that has been around for millennia in many cultures. We have discussed it repeatedly on this blog (see, for instance, here, here, and here). This new study tested the effects of dry cupping on pain intensity, physical function, functional mobility, trunk range of motion, perceived overall effect, quality of life, psychological symptoms, and medication use in individuals with chronic non-specific low back pain.

Ninety participants with chronic non-specific low back pain were randomized. The experimental group (n = 45) received dry cupping therapy, with cups bilaterally positioned parallel to the L1 to L5 vertebrae. The control group (n = 45) received sham cupping therapy. The interventions were applied once a week for 8 weeks.

Participants were assessed before and after the first treatment session, and after 4 and 8 weeks of intervention. The primary outcome was pain intensity, measured with the numerical pain scale at rest, during fast walking, and during trunk flexion. Secondary outcomes were physical function, functional mobility, trunk range of motion, perceived overall effect, quality of life, psychological symptoms, and medication use.

On a 0-to-10 scale, the between-group difference in pain severity at rest was negligible: MD 0.0 (95% CI -0.9 to 1.0) immediately after the first treatment, 0.4 (95% CI -0.5 to 1.5) at 4 weeks and 0.6 (95% CI -0.4 to 1.6) at 8 weeks. Similar negligible effects were observed on pain severity during fast walking or trunk flexion. Negligible effects were also found on physical function, functional mobility, and perceived overall effect, where mean estimates and their confidence intervals all excluded worthwhile effects. No worthwhile benefits could be confirmed for any of the remaining secondary outcomes.

The authors concluded that dry cupping therapy was not superior to sham cupping for improving pain, physical function, mobility, quality of life, psychological symptoms or medication use in people with non-specific chronic low back pain.

These results will not surprise many of us; they certainly don’t baffle me. What I found interesting in this paper was the concept of sham cupping therapy. How did they do it? Here is their explanation:

For the experimental group, a manual suction pump and four acrylic cups size one (internal diameter = 4.5 cm) were used for the interventions. The cups were applied to the lower back, parallel to L1 to L5 vertebrae, with a 3-cm distance between them, bilaterally. The dry cupping application consisted of a negative pressure of 300 millibars (two suctions in the manual suction pump) sustained for 10 minutes once a week for 8 weeks.

In the control group, the exact same procedures were used except that the cups were prepared with small holes < 2 mm in diameter to release the negative pressure in approximately 3 seconds. Double-sided adhesive tape was applied to the border of the cups in order to keep them in contact with the participants’ skin.

So, sham-controlled trials of cupping are doable. Future trialists might now consider the inclusion of testing the success of patient-blinding when conducting trials of cupping therapy.

I came across this article via a German secondary report about it entitled “Scientists discover what else protects from severe symptoms” (Forscher finden heraus, was noch vor schweren Symptomen schützt). The article rightly stressed that vaccination is paramount and then explains that, once you have caught COVID, nutrition can prevent serious symptoms.

Even though I rarely discuss standard nutritional issues on my blog (nutrition belongs to mainstream not so-called alternative medicine [SCAM], in my view), this subject did attract my attention. Here are the essentials of the original scientific paper:

Australian scientists studied the association between habitual frequency of food intake of certain food groups during the COVID-19 pandemic and manifestations of COVID-19 symptoms in adult outpatients with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection. They included 236 patients who attended an outpatient clinic for suspected COVID-19 evaluation. Severity of symptoms, habitual food intake frequency, demographics and Bristol chart scores were obtained before diagnostic confirmation with real-time reverse transcriptase PCR using nasopharyngeal swab.

The results of the COVID-19 diagnostic tests were positive for 103 patients (44%) and negative for 133 patients (56%). In the SARS-CoV-2-positive group, symptom severity scores had significant negative correlations with the habitual intake frequency of specific food groups. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, and occupation confirmed that SARS-CoV-2-positive patients showed a significant negative association between having higher symptom severity and the habitual intake frequency of legumes and grains, bread, and cereals.

The authors concluded that an increase in habitual frequency of intake of ‘legumes’, and ‘grains, bread and cereals’ food groups decreased overall symptom severity in patients with COVID-19. This study provides a framework for designing a protective diet during the COVID-19 pandemic and also establishes a hypothesis of using a diet-based intervention in the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may be explored in future studies.

So, the authors seem to think that they found a causal relationship: A CHANGE IN DIET DECREASES SYMPTOMS. In different sections of the article, they seem to confirm this notion, and they state that they tested the hypothesis of the effect of diet on SARS-CoV-2 infection symptom severity.

Yey, the investigation was merely a correlative study that cannot establish cause and effect. There are many other variables that might be linked to dietary habits which could be the true cause of the observed phenomenon (or contributors to it).

What’s the harm? If the article makes people adopt a healthier diet, all is pukka!

Perhaps, in this case, that might be true (even though one could argue that this paper might support anti-vax notions arguing that vaccination is not important if it is possible to prevent severe symptoms through dietary changes). But the confusion of correlation with causality is both frequent and potentially harmful. And it is unquestionably poor science!

I feel that we need to be concerned about the fact that even reputable journals let such things pass – not least because the above example shows what the popular press subsequently can make of such misleading messages.

This study assessed the effectiveness of Oscillococcinum in the protection from upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) in patients with COPD who had been vaccinated against influenza infection over the 2018-2019 winter season.

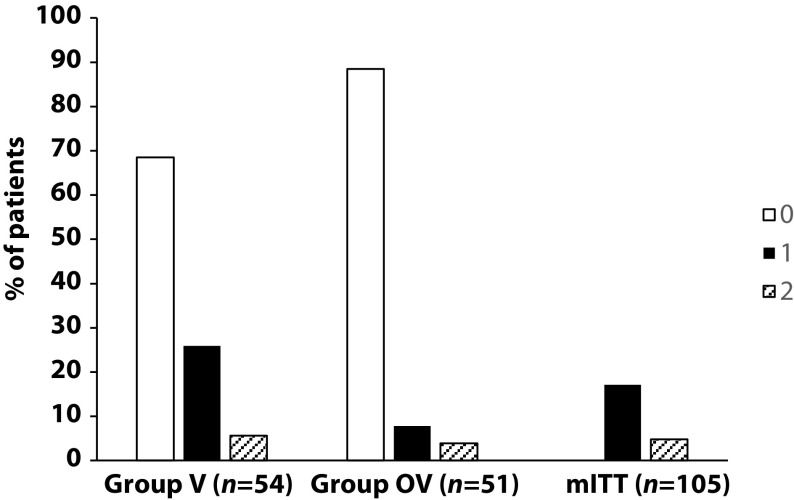

A total of 106 patients were randomized into two groups:

- group V received influenza vaccination only

- group OV received influenza vaccination plus Oscillococcinum® (one oral dose per week from inclusion in the study until the end of follow-up, with a maximum of 6 months follow-up over the winter season).

The primary endpoint was the incidence rate of URTIs (number of URTIs/1000 patient-treatment exposure days) during follow-up compared between the two groups.

There was no significant difference in any of the demographic characteristics, baseline COPD, or clinical data between the two treatment groups (OV and V). The URTI incidence rate was significantly higher in group V than in group OV (2.9 versus 1.2 episodes/1000 treatment days, difference OV-V = -1.7; p=0.0312). There was a significant delay in occurrence of an URTI episode in the OV group versus the V group (mean ± standard error: 48.7 ± 3.0 versus 67.0 ± 2.8 days, respectively; p=0.0158). Limitations to this study include its small population size and the self-recording by patients of the number and duration of URTIs and exacerbations.

The authors concluded that the use of Oscillococcinum in patients with COPD led to a significant decrease in incidence and a delay in the appearance of URTI symptoms during the influenza-exposure period. The results of this study confirm the impact of this homeopathic medication on URTIs in patients with COPD.

Primary endpoint, comparison of the number of upper respiratory tract infections in the two treatment groups during follow-up

This prospective, randomized, single-center study was funded by Laboratoires Boiron, was conducted in the Pneumology Department of Charles Nicolle Hospital, Tunis, and was written up by a commercial firm specializing in writing for the pharmaceutical industry. The latter point may explain why it reads well and elegantly glosses over the many flaws of the trial.

If I did not know better, I might suspect that the study was designed to deceive us (Boiron would, of course, never do this!): The primary endpoint was the incidence rate of URTIs (number of URTIs/1000 patient-treatment exposure days) in the two groups during the follow-up period. This rate is calculated as the number of episodes of URTIs per 1000 days of follow-up/treatment exposure. The rates were then compared between the OV and V groups. The following symptoms were considered indicative of an URTI: fever, shivering, runny or blocked nose, sneezing, muscular aches/pain, sore throat, watery eyes, headaches, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, fatigue and loss of appetite.

This means that there was no verification whatsoever of the primary endpoint. In itself, this flaw would perhaps not be so bad. But put it together with the fact that patients were not blinded (there were no placebos!), it certainly is fatal.

In essence, the study shows that patients who perceive to receive treatment will also perceive to have fewer URTIs.

SURPRISE, SURPRISE!

The ‘Control Group Cooperative Ltd‘ is a UK Company (Registration Number: 13477806) is registered at 117 Dartford Road, Dartford, Kent DA1 3EN, UK. On its website, it provides the following statement:

The Vaccine Control Group is a Worldwide independent long-term study that is seeking to provide a baseline of data from unvaccinated individuals for comparative analysis with the vaccinated population, to evaluate the success of the Covid-19 mass vaccination programme and assist future research projects. This study is not, and will never be, associated with any pharmaceutical enterprise as its impartiality is of paramount importance.

The VaxControlGroup is a community cooperative, for the people. All monies raised will be re-invested into the project and its community.

Volunteers for this study are welcome from around the world, providing they have not yet received any of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and are not planning to do so.

So, the Vaccine Control Group (VCC) aims at recruiting people who refuse COVID vaccinations. The VCC issues downloadable and printable COVID-19 Vaccine self exemption forms that you can complete (either online or by hand) supplied by: Professionals for Medical Informed Consent and Non-Discrimination (PROMIC). The form contains the following text:

COVID-19 vaccines, that have been administered to the public under emergency use authorisation, have been

associated with moderate to severe adverse events and deaths in a small proportion of recipients. There are currently insufficient available long-term safety data from Phase 3 trials and post-marketing surveillance to be able to predict which population sub-groups are likely to be most vulnerable to these reactions. However, clinical assessments have identified a range of conditions or medical histories that are associated with increased risk of serious adverse events (see Panel B). Individuals with such medical concerns, along with those who have already had COVID-19 and acquired natural immunity, have justifiable grounds to not consent to COVID-19 vaccination. Such individuals may choose to use alternate approaches to reduce their risk of developing serious COVID-19 disease and associated viral transmission. UK and international law enshrines an individual’s right to refuse any medical treatment or intervention without being subjected to penalty, restriction or limitation of protected rights or freedoms, as this would otherwise constitute coercion.

I do wonder, after reading this, what scientific value this ‘study’ might have (nowhere could I find relevant methodological details about the ‘study’). In search of an answer, I found ‘Doctors & Health Professionals supportive of this project’. The only one supportive of the VCC seems to be Prof Harald Walach who offers his support with these words:

A vaccine control group, especially for Covid-19 vaccines, is extremely useful, even necessary, for the following reasons:

- We are dealing with a vaccination technology that has never been used in humans before.

- All studies that have planned a control group long term, i.e. longer than only 6 weeks, have meanwhile been compromised, i.e. there are no real control groups around, because those originally allocated to the control group have mostly been vaccinated now. So there are no real control groups available.

- Covid-19 vaccinations are one of the biggest experiments on mankind ever conducted – without a control group. Hence those, who are either not willing to be vaccinated or have not yet been vaccinated are our only chance to understand whether the vaccines are safe or whether symptoms reported after vaccination are actually due to the vaccination or are only an incidental occurrence or random fluctuation.

Comparing unvaccinated people and those with a vaccination history regarding Covid-19 vaccines long term is important to determine long-term safety, because in many instances in the past some problems only were seen after quite some time. This can happen, if auto-immune processes are triggered, which often occur only in very few people. Hence, it is also important to have a long-term observation period and a large number of people participating.

Prof. Dr. Dr. phil. Harald Walach

This does not alleviate my doubts about the scientific value at all. Prof Walach, promoter of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and pseudoscientist of the year 2012, has in the past drawn our attention to his odd activities around COVID and vaccinations. Here are three recent posts on the subject:

- Prof Harald Walach is really unlucky

- Is Prof Harald Walach incompetent or dishonest?

- COVID-19 vaccinations: Prof Walach wants to “dampen the enthusiasm by sober facts”

In view of all this, I do wonder what the VCC is truly about.

It couldn’t be a front for issuing dodgy exemption certificates, could it?

Ovariohysterectomy (OH) is one of the most frequent elective surgical procedures in routine veterinary practice. The aim of this study was to evaluate analgesia with Arnica montana 30cH during the postoperative period after elective OH.

Thirty healthy female dogs, aged 1 to 3 years, weighing 7 to 14 kg, were selected at the Veterinary Hospital in Campo Mourão, Paraná, Brazil. The dogs underwent the surgical procedure with an anaesthetic protocol and analgesia that had the aim of maintaining the patient’s wellbeing. After the procedure, they were randomly divided into three groups of 10. One group received Arnica montana 30cH; another received 5% hydroalcoholic solution; and the third group, 0.9% NaCl saline solution. All animals received four drops of the respective solution sublingually and under blinded conditions, every 10 minutes for 1 hour, after the inhalational anaesthetic had been withdrawn. The Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scale was used to analyse the effect of therapy. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test was used to evaluate the test data. Statistical differences were deemed significant when p ≤0.05.

The results show that the Arnica montana 30cH group maintained analgesia on average for 17.8 ± 3.6 hours, whilst the hydroalcoholic solution group did so for 5.1 ± 1.2 hours and the saline solution group for 4.1 ± 0.9 hours (p ≤0.05).

The authors concluded that these data demonstrate that Arnica montana 30cH presented a more significant analgesic effect than the control groups, thus indicating its potential for postoperative analgesia in dogs undergoing OH.

I do not have access to the full article (I was fired by the late Peter Fisher from the editorial board of the journal ‘HOMEOPATHY’) which puts me in a somewhat difficult position:

- not reporting this study could be construed as an anti-homeopathy bias,

- and reporting it handicaps me as I cannot assess essential details.

So, if anyone has access, please send the full paper to me and I will then study it and revise this post accordingly.

Judging from the abstract, I have to say that the results seem far too good to be true. I doubt that any oral remedy can have the effect that is being described here – let alone one that has been diluted (sorry, potentised) at a rate of 1: 1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000. That fact alone reduces the plausibility of the finding to zero.

At this stage, I do wonder who peer-reviewed the study and ask myself whether the rough data have been checked for reliability.

Well-conducted systematic reviews (SRs) should in principle provide the most reliable evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture. However, limitations on the methodological rigour of SRs may impact the trustworthiness of their conclusions. This cross-sectional study was aimed at evaluating the methodological quality of recent SRs of acupuncture.

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, and EMBASE were searched for SRs focusing on manual acupuncture or electro-acupuncture published during January 2018 and March 2020. Eligible SRs needed to contain at least one meta-analysis and be published in the English language. Two independent reviewers extracted the bibliographical characteristics of the included SRs with a pre-designed questionnaire and appraised the methodological quality of the reviews with the validated AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews 2). The associations between bibliographical characteristics and methodological quality ratings were explored using Kruskal-Wallis rank tests and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients.

A total of 106 SRs were appraised. The results were as follows:

- one (0.9%) SR was of high methodological quality,

- no review (0%) was of moderate quality,

- six (5.7%) were of low quality,

- 99 (93.4%) were of critically low quality.

Only ten (9.4%) provided an a priori protocol, only four (3.8%) conducted a comprehensive literature search, only five (4.7%) provided a list of excluded studies, and only six (5.7%) performed a meta-analysis appropriately. Cochrane SRs, updated SRs, and SRs that did not search non-English databases had relatively higher overall quality. The vast majority (87.7%) of the 106 reviews included in this analysis originated from Asia. Conflicts of interest of the review authors were declared in only 2 of the 106 reviews.

The authors concluded that the methodological quality of SRs on acupuncture is unsatisfactory. Future reviewers should improve critical methodological aspects of publishing protocols, performing comprehensive search, providing a list of excluded studies with justifications for exclusion, and conducting appropriate meta-analyses. These recommendations can be implemented via enhancing the technical competency of reviewers in SR methodology through established education approaches as well as quality gatekeeping by journal editors and reviewers. Finally, for evidence users, skills in SR critical appraisal remain to be essential as relevant evidence may not be available in pre-appraised formats.

On this blog, I have often complained about the lack of critical input and the poor quality of systematic reviews of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), particularly of acupuncture, and especially of Chinese reviews, and even more especially Chinese reviews of (mostly) Chinese studies. This new paper is a valuable confirmation of this fast-growing deficit.

One does not need to be a prophet to predict that this pollution of the literature with complete rubbish will have detrimental effects. Because poor reviews almost always draw an over-optimistic picture of the value of acupuncture, this phenomenon must seriously mislead the public. The end result will be that the public believes acupuncture to be effective.

I cannot help thinking that this is, in fact, the intended aim of the authors of such poor, false-positive reviews. Moreover, a glance at the subject areas of the reviews in the list below gives the impression that China is heavily promoting the idea that acupuncture is a panacea. Yet there is good evidence to show that acupuncture is little more than placebo therapy.

In my last post, I have reported that I am an author of many of the frequently-cited systematic acupuncture reviews. You might thus assume that I am a significant part of this pollution by rubbish reviews. This would, however, be an entirely wrong conclusion. The above analysis covers a period when my unit had already been closed, and I am thus not responsible for a single of the papers included in the above analysis.

List of included systematic reviews

| ID | Included systematic reviews |

| 1 | Acupuncture for primary insomnia: An updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials |

| 2 | Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for essential hypertension: A meta-analysis |

| 3 | Acupuncture for the treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Acupuncture for SSNHL |

| 4 | Effectiveness of Acupuncturing at the Sphenopalatine Ganglion Acupoint Alone for Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 5 | Acupuncture and clomiphene citrate for anovulatory infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 6 | Acupuncture for primary trigeminal neuralgia: A systematic review and PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis |

| 7 | Acupuncture as an adjunctive treatment for angina due to coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis |

| 8 | Conventional treatments plus acupuncture for asthma in adults and adolescent: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 9 | Optimizing acupuncture treatment for dry eye syndrome: A systematic review |

| 10 | Acupuncture using pattern-identification for the treatment of insomnia disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 11 | Efficacy and Safety of Auricular Acupuncture for Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Systematic Review |

| 12 | Acupuncture for cognitive impairment in vascular dementia, alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 13 | Effectiveness of pharmacopuncture for cervical spondylosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 14 | Acupuncture combined with swallowing training for poststroke dysphagia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials |

| 15 | Scalp acupuncture treatment for children’s autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 16 | Acupuncture for Post-stroke Shoulder-Hand Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 17 | Systematic review of acupuncture for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome |

| 18 | Acupuncture for hip osteoarthritis |

| 19 | Clinical Benefits of Acupuncture for the Reduction of Hormone Therapy-Related Side Effects in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review |

| 20 | Combination therapy of scalp electro-acupuncture and medication for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 21 | Acupuncture for migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 22 | Acupuncture to Promote Recovery of Disorder of Consciousness after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 23 | Acupuncture Compared with Intramuscular Injection of Neostigmine for Postpartum Urinary Retention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials |

| 24 | Acupuncture for the relief of hot flashes in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies |

| 25 | Effectiveness and Safety of Acupuncture for Perimenopausal Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials |

| 26 | Acupuncture plus Chinese Herbal Medicine for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 27 | Electroacupuncture as an adjunctive therapy for motor dysfunction in acute stroke survivors: A systematic review and meta-analyses |

| 28 | Acupuncture for Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis |

| 29 | Acupuncture for chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 30 | Compare the efficacy of acupuncture with drugs in the treatment of Bell’s palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs |

| 31 | The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for the treatment of myasthenia gravis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 32 | Acupuncture therapy for fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 33 | The effectiveness of acupuncture therapy in patients with post-stroke depression: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 34 | Fire needling for herpes zoster: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials |

| 35 | Comparison between the Effects of Acupuncture Relative to Other Controls on Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis |

| 36 | Manual Acupuncture for Optic Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 37 | Effect of warm needling therapy and acupuncture in the treatment of peripheral facial paralysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 38 | The Effect of Acupuncture in Breast Cancer-Related Lymphoedema (BCRL): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 39 | The Efficacy of Acupuncture in Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 40 | The maintenance effect of acupuncture on breast cancer-related menopause symptoms: a systematic review |

| 41 | The effectiveness of acupuncture in the management of persistent regional myofascial head and neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 42 | Acupuncture for the Treatment of Adults with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 43 | The effectiveness of superficial versus deep dry needling or acupuncture for reducing pain and disability in individuals with spine-related painful conditions: a systematic review with meta-analysis |

| 44 | Effects of dry needling trigger point therapy in the shoulder region on patients with upper extremity pain and dysfunction: a systematic review with meta-analysis |

| 45 | Is dry needling effective for low back pain?: A systematic review and PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis |

| 46 | The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for patients with atopic eczema: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 47 | Comparing verum and sham acupuncture in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 48 | Acupuncture for symptomatic gastroparesis |

| 49 | The Efficacy and Safety of Acupuncture for the Treatment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 50 | Acupuncture Versus Sham-acupuncture: A Meta-analysis on Evidence for Non-immediate Effects of Acupuncture in Musculoskeletal Disorders |

| 51 | Acupuncture Treatment for Post-Stroke Dysphagia: An Update Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials |

| 52 | Effectiveness of Acupuncture Used for the Management of Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 53 | Clinical effects and safety of electroacupuncture for the treatment of post-stroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials |

| 54 | Placebo effect of acupuncture on insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 55 | Acupuncture for Chronic Pain-Related Insomnia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 56 | Evidence for Dry Needling in the Management of Myofascial Trigger Points Associated With Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 57 | Warm needle acupuncture in primary osteoporosis management: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 58 | Acupuncture for overactive bladder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 59 | Traditional acupuncture for menopausal hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 60 | The effectiveness of acupuncture for osteoporosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 61 | Long-term effects of acupuncture for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Systematic review and single-Arm meta-Analyses |

| 62 | Does acupuncture the day of embryo transfer affect the clinical pregnancy rate? Systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 63 | Acupuncture treatments for infantile colic: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of blinding test validated randomised controlled trials |

| 64 | Acupuncture performed around the time of embryo transfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 65 | Is Acupuncture Effective for Improving Insulin Resistance? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis |

| 66 | Efficacy of acupuncture in the management of post-apoplectic aphasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 67 | Acupuncture for lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 68 | Traditional Chinese acupuncture and postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 69 | Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Update of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis |

| 70 | Acupuncture Therapy for Functional Effects and Quality of Life in COPD Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 71 | Electroacupuncture for Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy after Stroke: A Meta-Analysis |

| 72 | The Effect of Patient Characteristics on Acupuncture Treatment Outcomes |

| 73 | The efficacy and safety of acupuncture in women with primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 74 | Role of acupuncture in the treatment of insulin resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 75 | Appropriateness of sham or placebo acupuncture for randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for nonspecific low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 76 | Evidence of efficacy of acupuncture in the management of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo- or sham-controlled trials |

| 77 | The effects of acupuncture on pregnancy outcomes of in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 78 | Acupuncture for migraine without aura: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 79 | Acupuncture for acute stroke |

| 80 | Acupuncture at Tiaokou (ST38) for Shoulder Adhesive Capsulitis: What Strengths Does It Have? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials |

| 81 | Acupuncture for hypertension |

| 82 | The effect of acupuncture on Bell’s palsy: An overall and cumulative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 83 | Effects of acupuncture on cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis |

| 84 | Acupuncture for adults with overactive bladder |

| 85 | Electroacupuncture for Postoperative Urinary Retention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 86 | Meta-Analysis of Electroacupuncture in Cardiac Anesthesia and Intensive Care |

| 87 | Acupuncture therapy improves health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 88 | The effect of acupuncture on the quality of life in patients with migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 89 | Cognitive improvement effects of electro-acupuncture for the treatment of MCI compared with Western medications: A systematic review and Meta-analysis 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1103 Clinical Sciences |

| 90 | Oriental herbal medicine and moxibustion for polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis |

| 91 | The Effect of Acupuncture and Moxibustion on Heart Function in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 92 | Acupuncture therapy for the treatment of stable angina pectoris: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 93 | Traditional manual acupuncture combined with rehabilitation therapy for shoulder hand syndrome after stroke within the Chinese healthcare system: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 94 | Effects of moxibustion on pain behaviors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis |

| 95 | Acupuncture Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials |

| 96 | The effectiveness of dry needling for patients with orofacial pain associated with temporomandibular dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 97 | Acupuncture for postherpetic neuralgia systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 98 | Acupoint selection for the treatment of dry eye: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 99 | Warm-needle moxibustion for spasticity after stroke: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials |

| 100 | Acupuncture for menstrual migraine: a systematic review |

| 101 | The efficacy of acupuncture for stable angina pectoris: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 102 | Acupuncture and weight loss in Asians: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 103 | Effects of Acupuncture on Breast Cancer-Related lymphoedema: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| 104 | Acupuncture for infertile women without undergoing assisted reproductive techniques (ART): A systematic review and meta-analysis |

| 105 | Moxibustion for alleviating side effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy in people with cancer |

| 106 | Acupuncture for stable angina pectoris: A systematic review and meta-analysis |

Therapeutic touch (TT) is a form of paranormal or energy healing developed by Dora Kunz (1904-1999), a psychic and alternative practitioner, in collaboration with Dolores Krieger, a professor of nursing. TT is popular and practised predominantly by US nurses; it is currently being taught in more than 80 colleges and universities in the U.S., and in more than seventy countries. According to one TT-organisation, TT is a holistic, evidence-based therapy that incorporates the intentional and compassionate use of universal energy to promote balance and well-being. It is a consciously directed process of energy exchange during which the practitioner uses the hands as a focus to facilitate the process.

The question is: does TT work beyond a placebo effect?

This review synthesized recent (January 2009–June 2020) investigations on the effectiveness and safety of therapeutic touch (TT) as a therapy in clinical health applications. A rapid evidence assessment (REA) approach was used to review recent TT research adopting PRISMA 2009 guidelines. CINAHL, PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane databases, Web of Science, PsychINFO, and Google Scholar were screened between January 2009-March 2020 for studies exploring TT therapies as an intervention. The main outcome measures were for pain, anxiety, sleep, nausea, and functional improvement.

Twenty-one studies covering a range of clinical issues were identified, including 15 randomized controlled trials, four quasi-experimental studies, one chart review study, and one mixed-methods study including 1,302 patients. Eighteen of the studies reported positive outcomes. Only four exhibited a low risk of bias. All others had serious methodological flaws, bias issues, were statistically underpowered, and scored as low-quality studies. Over 70% of the included studies scored the lowest score possible on the GSRS weight of evidence scale. No high-quality evidence was found for any of the benefits claimed.

The authors drew the following conclusions:

After 45 years of study, scientific evidence of the value of TT as a complementary intervention in the management of any condition still remains immature and inconclusive:

- Given the mixed result, lack of replication, overall research quality and significant issues of bias identified, there currently exists no good quality evidence that supports the implementation of TT as an evidence‐based clinical intervention in any context.

- Research over the past decade exhibits the same issues as earlier work, with highly diverse poor quality unreplicated studies mainly published in alternative health media.

- As the nature of human biofield energy remains undemonstrated, and that no quality scientific work has established any clinically significant effect, more plausible explanations of the reported benefits are from wishful thinking and use of an elaborate theatrical placebo.

TT turns out to be a prime example of a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that enthusiastic amateurs, who wanted to prove TT’s effectiveness, have submitted to multiple trials. Thus the literature is littered with positive but unreliable studies. This phenomenon can create the impression – particularly to TT fans – that the treatment works.

This course of events shows in an exemplary fashion that research is not always something that creates progress. In fact, poor research often has the opposite effect. Eventually, a proper scientific analysis is required to put the record straight (the findings of which enthusiasts are unlikely to accept).

In view of all this, and considering the utter implausibility of TT, it seems an unethical waste of resources to continue researching the subject. Similarly, continuing to use TT in clinical settings is unethical and potentially dangerous.

Kneipp therapy goes back to Sebastian Kneipp (1821-1897), a catholic priest who was convinced to have cured himself of tuberculosis by using various hydrotherapies. Kneipp is often considered by many to be ‘the father of naturopathy’. Kneipp therapy consists of hydrotherapy, exercise therapy, nutritional therapy, phototherapy, and ‘order’ therapy (or balance). Kneipp therapy remains popular in Germany where whole spa towns live off this concept.

The obvious question is: does Kneipp therapy work? A team of German investigators has tried to answer it. For this purpose, they conducted a systematic review to evaluate the available evidence on the effect of Kneipp therapy.

A total of 25 sources, including 14 controlled studies (13 of which were randomized), were included. The authors considered almost any type of study, regardless of whether it was a published or unpublished, a controlled or uncontrolled trial. According to EPHPP-QAT, 3 studies were rated as “strong,” 13 as “moderate” and 9 as “weak.” Nine (64%) of the controlled studies reported significant improvements after Kneipp therapy in a between-group comparison in the following conditions:

- chronic venous insufficiency,

- hypertension,

- mild heart failure,

- menopausal complaints,

- sleep disorders in different patient collectives,

- as well as improved immune parameters in healthy subjects.

No significant effects were found in:

- depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients with climacteric complaints,

- quality of life in post-polio syndrome,

- disease-related polyneuropathic complaints,

- the incidence of cold episodes in children.

Eleven uncontrolled studies reported improvements in allergic symptoms, dyspepsia, quality of life, heart rate variability, infections, hypertension, well-being, pain, and polyneuropathic complaints.

The authors concluded that Kneipp therapy seems to be beneficial for numerous symptoms in different patient groups. Future studies should pay even more attention to methodologically careful study planning (control groups, randomisation, adequate case numbers, blinding) to counteract bias.

On the one hand, I applaud the authors. Considering the popularity of Kneipp therapy in Germany, such a review was long overdue. On the other hand, I am somewhat concerned about their conclusions. In my view, they are far too positive:

- almost all studies had significant flaws which means their findings are less than reliable;

- for most indications, there are only one or two studies, and it seems unwarranted to claim that Kneipp therapy is beneficial for numerous symptoms on the basis of such scarce evidence.

My conclusion would therefore be quite different:

Despite its long history and considerable popularity, Kneipp therapy is not supported by enough sound evidence for issuing positive recommendations for its use in any health condition.

Cannabis seems often to be an emotional subject where more heat than light is generated. Does it work for chronic pain? This cannot be such a difficult question to answer definitively. Yet, systematic reviews have provided conflicting results due, in part, to limitations of analytical approaches and interpretation of findings.

A new systematic review is therefore both necessary and welcome. It aimed at determining the benefits and harms of medical cannabis and cannabinoids for chronic pain. Included were all randomised clinical trials of medical cannabis or cannabinoids versus any non-cannabis control for chronic pain at ≥1-month follow-up.

A total of 32 trials with 5174 adult patients were included, 29 of which compared medical cannabis or cannabinoids with placebo. Medical cannabis was administered orally (n=30) or topically (n=2). Clinical populations included chronic non-cancer pain (n=28) and cancer-related pain (n=4). Length of follow-up ranged from 1 to 5.5 months.

Compared with placebo, non-inhaled medical cannabis probably results in a small increase in the proportion of patients experiencing at least the minimally important difference (MID) of 1 cm (on a 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS)) in pain relief (modelled risk difference (RD) of 10% (95% confidence interval 5% to 15%), based on a weighted mean difference (WMD) of −0.50 cm (95% CI −0.75 to −0.25 cm, moderate certainty)). Medical cannabis taken orally results in a very small improvement in physical functioning (4% modelled RD (0.1% to 8%) for achieving at least the MID of 10 points on the 100-point SF-36 physical functioning scale, WMD of 1.67 points (0.03 to 3.31, high certainty)), and a small improvement in sleep quality (6% modelled RD (2% to 9%) for achieving at least the MID of 1 cm on a 10 cm VAS, WMD of −0.35 cm (−0.55 to −0.14 cm, high certainty)). Medical cannabis taken orally does not improve emotional, role, or social functioning (high certainty). Moderate certainty evidence shows that medical cannabis taken orally probably results in a small increased risk of transient cognitive impairment (RD 2% (0.1% to 6%)), vomiting (RD 3% (0.4% to 6%)), drowsiness (RD 5% (2% to 8%)), impaired attention (RD 3% (1% to 8%)), and nausea (RD 5% (2% to 8%)), but not diarrhoea; while high certainty evidence shows greater increased risk of dizziness (RD 9% (5% to 14%)) for trials with <3 months follow-up versus RD 28% (18% to 43%) for trials with ≥3 months follow-up; interaction test P=0.003; moderate credibility of subgroup effect).

The authors concluded that moderate to high certainty evidence shows that non-inhaled medical cannabis or cannabinoids results in a small to very small improvement in pain relief, physical functioning, and sleep quality among patients with chronic pain, along with several transient adverse side effects, compared with placebo.

This is a high-quality review. Its findings will disappoint the many advocates of cannabis as a therapy for chronic pain management. The bottom line, I think, seems to be that cannabis works but the effect is not very powerful, while we have treatments for managing chronic pain that are both more effective and arguably less risky. So, its place in clinical routine is debatable.

PS

Cannabis is, of course, a herbal remedy and therefore belongs to so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Yet, I am aware that the medical cannabis preparations used in most studies are based on single cannabinoids which makes them conventional medicines.

This systematic review assessed the effect of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), the hallmark therapy of chiropractors, on pain and function for chronic low back pain (LBP) using individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses.

Of the 42 RCTs fulfilling the inclusion criteria, the authors obtained IPD from 21 (n=4223). Most trials (s=12, n=2249) compared SMT to recommended interventions. The analyses showed moderate-quality evidence that SMT vs recommended interventions resulted in similar outcomes on

- pain (MD -3.0, 95%CI: -6.9 to 0.9, 10 trials, 1922 participants)

- and functional status at one month (SMD: -0.2, 95% CI -0.4 to 0.0, 10 trials, 1939 participants).

Effects at other follow-up measurements were similar. Results for other comparisons (SMT vs non-recommended interventions; SMT as adjuvant therapy; mobilization vs manipulation) showed similar findings. SMT vs sham SMT analysis was not performed, because data from only one study were available. Sensitivity analyses confirmed these findings.

The authors concluded that sufficient evidence suggest that SMT provides similar outcomes to recommended interventions, for pain relief and improvement of functional status. SMT would appear to be a good option for the treatment of chronic LBP.

In 2019, this team of authors published a conventional meta-analysis of almost the same data. At this stage, they concluded as follows: SMT produces similar effects to recommended therapies for chronic low back pain, whereas SMT seems to be better than non-recommended interventions for improvement in function in the short term. Clinicians should inform their patients of the potential risks of adverse events associated with SMT.

Why was the warning about risks dropped in the new paper?

I have no idea.

But the risks are crucial here. If we are told that SMT is as good or as bad as recommended therapies, such as exercise, responsible clinicians need to decide which treatment they should recommend to their patients. If effectiveness is equal, other criteria come into play:

- cost,

- risk,

- availability.

Can any reasonable person seriously assume that SMT would do better than exercise when accounting for costs and risks?

I very much doubt it!