methodology

This study examined the incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs) of patients receiving chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), with the hypothesis that < 1 per 100,000 SMT sessions results in a grade ≥ 3 (severe) AE. A secondary objective was to examine independent predictors of grade ≥ 3 AEs.

The researchers retrospectively identified patients with SMT-related AEs from January 2017 through August 2022 across 30 chiropractic clinics in Hong Kong. AE data were extracted from a complaint log, including solicited patient surveys, complaints, and clinician reports, and corroborated by medical records. AEs were independently graded 1–5 based on severity (1-mild, 2-moderate, 3-severe, 4-life-threatening, 5-death).

Among 960,140 SMT sessions for 54,846 patients, 39 AEs were identified, two were grade 3, both of which were rib fractures occurring in women age > 60 with osteoporosis, while none were grade ≥ 4, yielding an incidence of grade ≥ 3 AEs of 0.21 per 100,000 SMT sessions (95% CI 0.00, 0.56 per 100,000). There were no AEs related to stroke or cauda equina syndrome. The sample size was insufficient to identify predictors of grade ≥ 3 AEs using multiple logistic regression.

The authors concluded that, in this study, severe SMT-related AEs were reassuringly very rare.

This is good news for all patients who consult chiropractors. However, there seem to be several problems with this study:

- Data originated from 30 affiliated chiropractic clinics with 38 chiropractors (New York Chiropractic & Physiotherapy Center, EC Healthcare, Hong Kong). These clinics are integrated into a larger healthcare organization, including several medical specialties and imaging and laboratory testing centers that utilize a shared medical records system. The 38 chiropractors represent only a little more than 10% of all chiropractors working in Hanh Kong and are thus not representative of all chiropractors in that region. Is it possible that the participating chiropractors were better trained, more gentle, or more careful than the rest?

- Data regarding AEs was obtained from a detailed complaint log that was routinely aggregated from several sources by a customer service department. One source of AEs in this log was a custom survey administered to patients after their 1st, 2nd, and 16th visits. Additional AEs derived from follow-up phone calls by a personal health manager. This means that not all AE might have been noted. Some patients might not have complained, others might have been too ill to do so. And, of course, dead patients cannot complain. The authors state that “the response to the SMS questionnaire was low. It is possible that severe AEs occurred but were not reported or recorded through these or other methods of ascertainment”.

- The 39 AEs potentially related to chiropractic SMT included increased symptoms related to the patient’s chief complaint (n = 28), chest pain without a fracture on imaging (n = 4), jaw pain (n = 3), rib fracture confirmed by imaging (n = 2), headache and dizziness without evidence of stroke (n = 1), and new radicular symptoms (n = 1). Of the 39 AEs, grade 2 were most common (n = 32, 82%), followed by grade 1 (n = 5, 13%), and grade 3 (n = 2, 5%). There were no cases of stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), vertebral or carotid artery dissection, cauda equina syndrome, or spinal fracture. Yet, headache and dizziness could be signs of a TIA.

- Calculating the rate of AEs per SMT session might be misleading and of questionable value. Are incidence rates of AEs not usually expressed as AE/patient? In this case, the % rate would be almost 20 times higher.

Altogether, this is a laudable effort to generate evidence for the risks of SMT. The findings seem reassuring but sadly they are not fully convincing.

Migraines are common headache disorders and risk factors for subsequent strokes. Acupuncture has been widely used in the treatment of migraines; however, few studies have examined whether its use reduces the risk of strokes in migraineurs. This study explored the long-term effects of acupuncture treatment on stroke risk in migraineurs using national real-world data.

A team of Taiwanese researchers collected new migraine patients from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2017. Using 1:1 propensity-score matching, they assigned patients to either an acupuncture or non-acupuncture cohort and followed up until the end of 2018. The incidence of stroke in the two cohorts was compared using the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Each cohort was composed of 1354 newly diagnosed migraineurs with similar baseline characteristics. Compared with the non-acupuncture cohort, the acupuncture cohort had a significantly reduced risk of stroke (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.35–0.46). The Kaplan–Meier model showed a significantly lower cumulative incidence of stroke in migraine patients who received acupuncture during the 19-year follow-up (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

The authors concluded that acupuncture confers protective benefits on migraineurs by reducing the risk of stroke. Our results provide new insights for clinicians and public health experts.

After merely 10 minutes of critical analysis, ‘real-world data’ turn out to be real-bias data, I am afraid.

The first question to ask is, were the groups at all comparable? The answer is, NO; the acupuncture group had

- more young individuals;

- fewer laborers;

- fewer wealthy people;

- fewer people with coronary heart disease;

- fewer individuals with chronic kidney disease;

- fewer people with mental disorders;

- more individuals taking multiple medications.

And that are just the variables that were known to the researcher! There will be dozens that are unknown but might nevertheless impact on a stroke prognosis.

But let’s not be petty and let’s forget (for a minute) about all these inequalities that render the two groups difficult to compare. The potentially more important flaw in this study lies elsewhere.

Imagine a group of people who receive some extra medical attention – such as acupuncture – over a long period of time, administered by a kind and caring therapist; imagine you were one of them. Don’t you think that it is likely that, compared to other people who do not receive this attention, you might feel encouraged to look better after your health? Consequently, you might do more exercise, eat more healthily, smoke less, etc., etc. As a result of such behavioral changes, you would be less likely to suffer a stroke, never mind the acupuncture.

SIMPLE!

I am not saying that such studies are totally useless. What often renders them worthless or even dangerous is the fact that the authors are not more self-critical and don’t draw more cautious conclusions. In the present case, already the title of the article says it all:

Acupuncture Is Effective at Reducing the Risk of Stroke in Patients with Migraines: A Real-World, Large-Scale Cohort Study with 19-Years of Follow-Up

My advice to researchers of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and journal editors publishing their papers is this: get your act together, learn about the pitfalls of flawed science (most of my books might assist you in this process), and stop misleading the public. Do it sooner rather than later!

In this study, the impact of a multimodal integrative oncology pre- and intraoperative intervention on pain and anxiety among patients undergoing gynecological oncology surgery was explored.

Study participants were randomized into three groups:

- Group A received preoperative touch/relaxation techniques, followed by intraoperative acupuncture, plus standard care;

- Group B received preoperative touch/relaxation only, plus standard care;

- Group C (the control group) received standard care.

Pain and anxiety were scored before and after surgery using the Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCAW) and Quality of Recovery (QOR-15) questionnaires, using Part B of the QOR to assess pain, anxiety, and other quality-of-life parameters.

A total of 99 patients participated in the study: 45 in Group A, 25 in Group B, and 29 in Group C. The three groups had similar baseline demographic and surgery-related characteristics. Postoperative QOR-Part B scores were significantly higher in the treatment groups (A and B) when compared with controls (p = .005), including for severe pain (p = .011) and anxiety (p = .007). Between-group improvement for severe pain was observed in Group A compared with controls (p = .011). Within-group improvement for QOR depression subscales was observed in only the intervention groups (p <0.0001). Compared with Group B, Group A had better improvement of MYCAW-reported concerns (p = .025).

The authors concluded that a preoperative touch/relaxation intervention may significantly reduce postoperative anxiety, possibly depression, in patients undergoing gynecological oncology surgery. The addition of intraoperative acupuncture significantly reduced severe pain when compared with controls. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and better understand the impact of intraoperative acupuncture on postoperative pain.

Regular readers of my blog know only too well what I am going to say about this study.

Imagine you have a basket full of apples and your friend has the same plus a basket full of pears. Who do you think has more fruit?

Dumb question, you say?

Correct!

Just as dumb, it seems, as this study: therapy A and therapy B will always generate better outcomes than therapy B alone. But that does not mean that therapy A per se is effective. Because therapy A generates a placebo effect, it might just be that it has no effect beyond placebo. And that acupuncture can generate placebo effects has been known for a very long time; to verify this we need no RCT.

As I have so often pointed out, the A+B versus B study design never generates a negative finding.

This is, I fear, precisely the reason why this design is so popular in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM)! It enables promoters of SCAM (who are not as dumb as the studies they conduct) to pretend they are scientists testing their therapies in rigorous RCTs.

The most disappointing thing about all this is perhaps that more and more top journals play along with this scheme to mislead the public!

Gut microbiota can influence health through the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Meditation can positively impact the regulation of an individual’s physical and mental health. However, few studies have investigated fecal microbiota following long-term (several years) deep meditation. Therefore, this study tested the hypothesis that long-term meditation may regulate gut microbiota homeostasis and, in turn, affect physical and mental health.

To examine the intestinal flora, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed on fecal samples of 56 Tibetan Buddhist monks and neighboring residents. Based on the sequencing data, linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was employed to identify differential intestinal microbial communities between the two groups. Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) analysis was used to predict the function of fecal microbiota. In addition, we evaluated biochemical indices in the plasma.

The α-diversity indices of the meditation and control groups differed significantly. At the genus level, Prevotella and Bacteroides were significantly enriched in the meditation group. According to the LEfSe analysis, two beneficial bacterial genera (Megamonas and Faecalibacterium) were significantly enriched in the meditation group. The functional predictive analysis further showed that several pathways—including glycan biosynthesis, metabolism, and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis—were significantly enriched in the meditation group. Moreover, plasma levels of clinical risk factors were significantly decreased in the meditation group, including total cholesterol and apolipoprotein B.

The Chinese authors concluded that the intestinal microbiota composition was significantly altered in Buddhist monks practicing long-term meditation compared with that in locally recruited control subjects. Bacteria enriched in the meditation group at the genus level had a positive effect on human physical and mental health. This altered intestinal microbiota composition could reduce the risk of anxiety and depression and improve immune function in the body. The biochemical marker profile indicates that meditation may reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases in psychosomatic medicine. These results suggest that long-term deep meditation may have a beneficial effect on gut microbiota, enabling the body to maintain an optimal state of health. This study provides new clues regarding the role of long-term deep meditation in regulating human intestinal flora, which may play a positive role in psychosomatic conditions and well-being.

This study is being mentioned on the BBC new-bulletins today – so I thought I have a look at it and check how solid it is. The most obvious question to ask is whether the researchers compared comparable samples.

The investigators collected a total of 128 samples. Subsequently, samples whose subjects had taken antibiotics and yogurt or samples of poor quality were excluded, resulting in 56 eligible samples. To achieve mind training, Tibetan Buddhist monks performed meditation practices of Samatha and Vipassana for at least 2 hours a day for 3–30 years (mean (SD) 18.94 (7.56) years). Samatha is the Buddhist practice of calm abiding, which steadies and concentrates the mind by resting the individual’s attention on a single object or mantra. Vipassana is an insightful meditation practice that enables one to enquire into the true nature of all phenomena. Hardly any information about the controls was provided.

This means that dozens of factors other than meditation could very easily be responsible for the observed differences; nutrition and lifestyle factors are obvious prime candidates. The fact that the authors fail to even discuss these possibilities and more than once imply a causal link between meditation and the observed outcomes is more than a little irritating, in my view. In fact, it amounts to very poor science.

I am dismayed that a respected journal published such an obviously flawed study without a critical comment and that the UK media lapped it up so naively.

It has been reported that a German consumer association, the ‘Verbraucherzentrale NRW’, has first cautioned the manufacturer MEDICE Arzneimittel Pütter GmbH & Co. and then sued them for misleading advertising statements. The advertisement in question gave the wrong impression that their homeopathic remedy MEDITONSIN would:

- for certain generate a health improvement,

- have no side effects,

- be superior to “chemical-synthetic drugs”.

The study used by the manufacturer in support of such claims was not convincing according to the Regional Court of Dortmund. The results of a “large-scale study with more than 1,000 patients” presented a pie chart indicating that 90% of the patients were satisfied or very satisfied with the effect of Meditonsin. However, this was only based on a “pharmacy-based observational study” with little scientific validity, as pointed out by the consumer association. Despite the lack of evidence, the manufacturer claimed that their study “once again impressively confirms the good efficacy and tolerability of Meditonsin® Drops”. The Regional Court of Dortmund disagreed with the manufacturer and agreed with the reasoning of the consumer association.

“It is not permitted to advertise with statements that give the false impression that a successful treatment can be expected with certainty, as suggested by the advertising for Meditonsin Drops,” emphasizes Gesa Schölgens, head of “Faktencheck Gesundheitswerbung,” a joint project of the consumer centers of North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate. According to German law, this is prohibited. In addition, the Regional Court of Dortmund considered consumers to be misled by the advertising because the false impression was created that no harmful side effects are to be expected when Meditonsin Drops are taken. The package insert of the drug lists several side effects, according to which there could even be an initial worsening of symptoms after taking the drug.

The claim of advantages of the “natural remedy” represented by the manufacturer in comparison with “chemical-synthetic medicaments, which merely suppress the symptoms”, was also deemed to be inadmissible. Such comparative advertising is inadmissible.

__________________________________

This ruling is, I think, interesting in several ways. The marketing claims of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) products seem all too often not within the limits of the laws. One can therefore hope that this case might inspire many more legal cases against the inadmissible advertising of SCAMs.

You, the readers of this blog, have spoken!

The WORST PAPER OF 2022 competition has concluded with a fairly clear winner.

To fill in those new to all this: over the last year, I selected articles that struck me as being of particularly poor quality. I then published them with my comments on this blog. In this way, we ended up with 10 papers, and you had the chance to nominate the one that, in your view, stood out as the worst. Votes came in via comments to my last post about the competition and via emails directly to me. A simple count identified the winner.

It is PAUL VARNAS, DC, a graduate of the National College of Chiropractic, US. He is the author of several books and has taught nutrition at the National University of Health Sciences. His award-winning paper is entitled “What is the goal of science? ‘Scientific’ has been co-opted, but science is on the side of chiropractic“. In my view, it is a worthy winner of the award (the runner-up was entry No 10). Here are a few memorable quotes directly from Paul’s article:

- Most of what chiropractors do in natural health care is scientific; it just has not been proven in a laboratory at the level we would like.

- In many ways we are more scientific than traditional medicine because we keep an open mind and study our observations.

- Traditional medicine fails to be scientific because it ignores clinical observations out of hand.

- When you think about it, in natural health care we are much better at utilizing the scientific process than traditional medicine.

But I am surely doing Paul an injustice. To appreciate his article, please read his article in full.

I am especially pleased that this award goes to a chiropractor who informs us about the value of science and research. The two research questions that undoubtedly need answering more urgently than any other in the realm of chiropractic relate to the therapeutic effectiveness and risks of chiropractic. I just had a quick look in Medline and found an almost complete absence of research from 2022 into these two issues. This, I believe, makes the award for the WORST PAPER OF 2022 all the more meaningful.

PS

Yesterday, I wrote to Paul informing him about the good news (as yet, no reply). Once he provides me with a postal address, I will send him a copy of my recent book on chiropractic as his well-earned prize. I have also invited him to contribute a guest post to this blog. Watch this space!

This meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) was aimed at evaluating the effects of massage therapy in the treatment of postoperative pain.

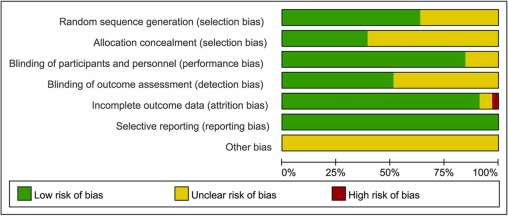

Three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) were searched for RCTs published from database inception through January 26, 2021. The primary outcome was pain relief. The quality of RCTs was appraised with the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool. The random-effect model was used to calculate the effect sizes and standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidential intervals (CIs) as a summary effect. The heterogeneity test was conducted through I2. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were used to explore the source of heterogeneity. Possible publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry.

The analysis included 33 RCTs and showed that MT is effective in reducing postoperative pain (SMD, -1.32; 95% CI, −2.01 to −0.63; p = 0.0002; I2 = 98.67%). A similarly positive effect was found for both short (immediate assessment) and long terms (assessment performed 4 to 6 weeks after the MT). Neither the duration per session nor the dose had a significant impact on the effect of MT, and there was no difference in the effects of different MT types. In addition, MT seemed to be more effective for adults. Furthermore, MT had better analgesic effects on cesarean section and heart surgery than orthopedic surgery.

The authors concluded that MT may be effective for postoperative pain relief. We also found a high level of heterogeneity among existing studies, most of which were compromised in the methodological quality. Thus, more high-quality RCTs with a low risk of bias, longer follow-up, and a sufficient sample size are needed to demonstrate the true usefulness of MT.

The authors discuss that publication bias might be possible due to the exclusion of all studies not published in English. Additionally, the included RCTs were extremely heterogeneous. None of the included studies was double-blind (which is, of course, not easy to do for MT). There was evidence of publication bias in the included data. In addition, there is no uniform evaluation standard for the operation level of massage practitioners, which may lead to research implementation bias.

Patients who have just had an operation and are in pain are usually thankful for the attention provided by carers. It might thus not matter whether it is provided by a massage or other therapist. The question is: does it matter? For the patient, it probably doesn’t; However, for making progress, it does, in my view.

In the end, we have to realize that, with clinical trials of certain treatments, scientific rigor can reach its limits. It is not possible to conduct double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of MT. Thus we can only conclude that, for some indications, massage seems to be helpful (and almost free of adverse effects).

This is also the conclusion that has been drawn long ago in some countries. In Germany, for instance, where I trained and practiced in my younger years, Swedish massage therapy has always been an accepted, conventional form of treatment (while exotic or alternative versions of massage therapy had no place in routine care). And in Vienna where I was chair of rehab medicine I employed about 8 massage therapists in my department.

This pilot study tested the feasibility of using US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–recommended endpoints to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of IBS. It was designed as a multicenter randomized clinical trial, conducted in 4 tertiary hospitals in China from July 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021, and 14-week data collection was completed in March 2021. Individuals with a diagnosis of IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) were randomized to 1 of 3 groups:

- acupuncture groups 1 (using specific acupoints [SA])

- acupuncture group 2 (using nonspecific acupoints [NSA])

- sham acupuncture group (non-acupoints [NA])

Patients in all groups received twelve 30-minute sessions over 4 consecutive weeks at 3 sessions per week, ideally every other day.

The primary outcome was the response rate at week 4, which was defined as the proportion of patients whose worst abdominal pain score (score range, 0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating unbearable severe pain) decreased by at least 30% and the number of type 6 or 7 stool days decreased by 50% or greater.

Ninety patients (54 male [60.0%]; mean [SD] age, 34.5 [11.3] years) were enrolled, with 30 patients in each group. There were substantial improvements in the primary outcomes for all groups

- response rates in the SA group = 46.7% [95% CI, 28.8%-65.4%]

- response rate in the NSA group = 46.7% [95% CI, 28.8%-65.4%]

- response rate in the NA group = 26.7% [95% CI, 13.0%-46.2%]

The difference between the groups was not statistically significant (P = .18). The response rates of adequate relief at week 4 were 64.3% (95% CI, 44.1%-80.7%) in the SA group, 62.1% (95% CI, 42.4%-78.7%) in the NSA group, and 55.2% (95% CI, 36.0%-73.0%) in the NA group (P = .76). Adverse events were reported in 2 patients (6.7%) in the SA group and 3 patients (10%) in NSA or NA group.

The authors concluded that acupuncture in both the SA and NSA groups showed clinically meaningful improvement in IBS-D symptoms, although there were no significant differences among the 3 groups. These findings suggest that acupuncture is feasible and safe; a larger, sufficiently powered trial is needed to accurately assess efficacy.

WHAT A LOAD OF TOSH!

Here are some of the most obvious issues I have with this new study:

- A pilot study is not about reporting effectiveness/efficacy but about testing the feasibility of a study.

- That acupuncture is feasible has been known for ~2000 years.

- The conclusion that acupuncture is safe is not warranted on the basis of the data; for that we would need a much larger investigation.

- The authors seem to have used our sham needle without acknowledging it.

- The authors are affiliated with the International Acupuncture and Moxibustion Innovation Institute, School of Acupuncture-Moxibustion and Tuina, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, yet they state that they have no conflicts of interest.

- The results are clearly negative, yet the authors seem to attempt to draw a positive conclusion.

The main question that occurs to me is this: how low has the JAMA sunk to publish such junk?

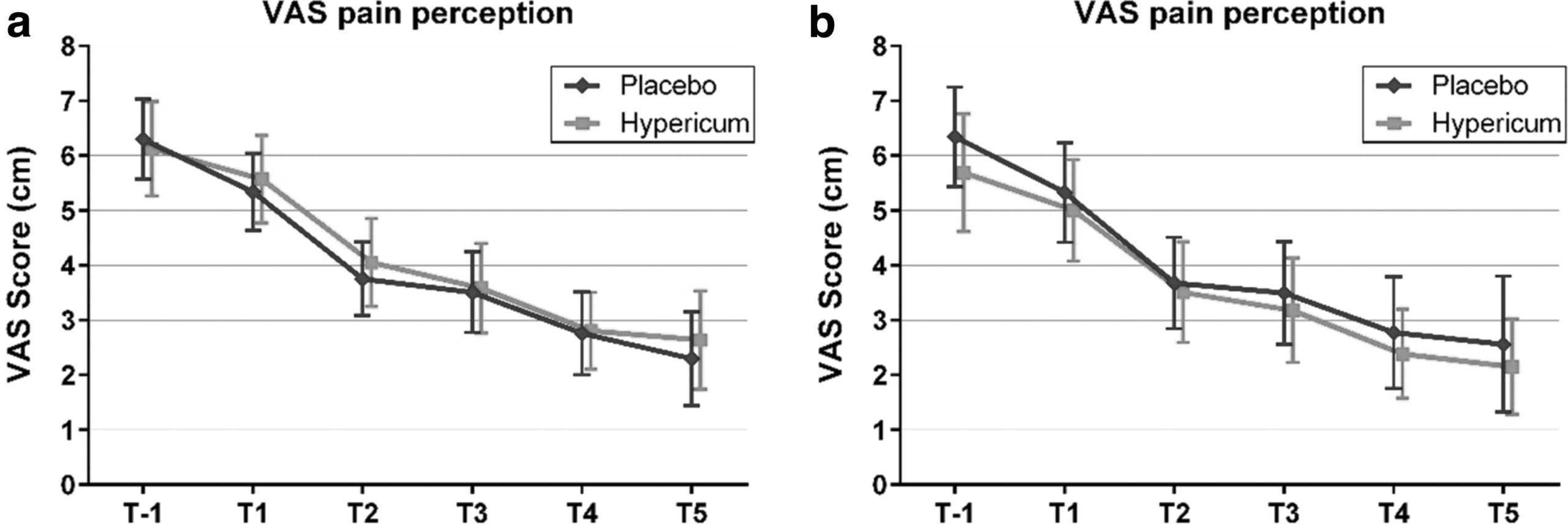

Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) is often recommended as a remedy to relieve pain caused by nerve damage. This trial investigated whether homeopathic Hypericum leads to a reduction in postoperative pain and a decrease in pain medication compared with placebo.

The study was designed as a randomized double-blind, monocentric, placebo-controlled clinical trial with inpatients undergoing surgery for lumbar sequestrectomy. Homeopathic treatment was compared to placebo, both in addition to usual pain management. The primary endpoint was pain relief measured with a visual analog scale. Secondary endpoints were the reduction of inpatient postoperative analgesic medication and change in sensory and affective pain perception.

The results show that the change in pain perception between baseline and day 3 did not significantly differ between the study arms. With respect to pain medication, total morphine equivalent doses did not differ significantly. However, a statistical trend and a moderate effect (d = 0.432) in the decrease of pain medication consumption in favor of the Hypericum group was observed.

The authors concluded that this is the first trial of homeopathy that evaluated the efficacy of Hypericum C200 after lumbar monosegmental spinal sequestrectomy. Although no significant differences between the groups could be shown, we found that patients who took potentiated Hypericum in addition to usual pain management showed lower consumption of analgesics. Further investigations, especially with regard to pain medication, should follow to better classify the described analgesic reduction.

For a number of reasons, this is a remarkably mysterious and quite hilarious study:

- Hypericum is recommended as an analgesic for neuropathic pain.

- According to the ‘like cures like’ axiom of homeopathy, it therefore must increase pain in such situations.

- Yet, the authors of this trial mounted an RCT to see whether it reduces pain.

- Thus they either do not understand homeopathy or wanted to sabotage it.

- As they are well-known pro-homeopathy researchers affiliated with a university that promotes homeopathy (Witten/Herdecke University, Herdecke, Germany), both explanations are highly implausible.

- The facts that the paper was published in a pro-SCAM journal (J Integr Complement Med), and the study was sponsored by the largest German firm of homeopathics (Deutsche Homoeopathische Union) renders all this even more puzzling.

- However, these biases do explain that the authors do their very best to mislead us by including some unwarranted ‘positive’ findings in their overall conclusions.

In the end, none of this matters, because the results of the study reveal that firstly the homeopathic ‘law of similars’ is nonsense, and secondly one homeopathic placebo (i.e. Hypericum C200) produces exactly the same outcomes as another, non-homeopathic placebo.

It’s again the season for nine lessons, I suppose. So, on the occasion of Christmas Eve, let me rephrase the nine lessons I once gave (with my tongue firmly lodged in my cheek) to those who want to make a pseudo-scientific career in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) research.

- Throw yourself into qualitative research. For instance, focus groups are a safe bet. They are not difficult to do: you gather 5 -10 people, let them express their opinions, record them, extract from the diversity of views what you recognize as your own opinion and call it a ‘common theme’, and write the whole thing up, and – BINGO! – you have a publication. The beauty of this approach is manifold:

-

- you can repeat this exercise ad nauseam until your publication list is of respectable length;

- there are plenty of SCAM journals that will publish your articles;

- you can manipulate your findings at will;

- you will never produce a paper that displeases the likes of King Charles;

- you might even increase your chances of obtaining funding for future research.

- Conduct surveys. They are very popular and highly respected/publishable projects in SCAM. Do not get deterred by the fact that thousands of similar investigations are already available. If, for instance, there already is one describing the SCAM usage by leg-amputated policemen in North Devon, you can conduct a survey of leg-amputated policemen in North Devon with a medical history of diabetes. As long as you conclude that your participants used a lot of SCAMs, were very satisfied with it, did not experience any adverse effects, thought it was value for money, and would recommend it to their neighbour, you have secured another publication in a SCAM journal.

- In case this does not appeal to you, how about taking a sociological, anthropological or psychological approach? How about studying, for example, the differences in worldviews, the different belief systems, the different ways of knowing, the different concepts about illness, the different expectations, the unique spiritual dimensions, the amazing views on holism – all in different cultures, settings or countries? Invariably, you must, of course, conclude that one truth is at least as good as the next. This will make you popular with all the post-modernists who use SCAM as a playground for enlarging their publication lists. This approach also has the advantage to allow you to travel extensively and generally have a good time.

- If, eventually, your boss demands that you start doing what (in his narrow mind) constitutes ‘real science’, do not despair! There are plenty of possibilities to remain true to your pseudo-scientific principles. Study the safety of your favourite SCAM with a survey of its users. You simply evaluate their experiences and opinions regarding adverse effects. But be careful, you are on thin ice here; you don’t want to upset anyone by generating alarming findings. Make sure your sample is small enough for a false negative result, and that all participants are well-pleased with their SCAM. This might be merely a question of selecting your patients wisely. The main thing is that your conclusions do not reveal any risks.

- If your boss insists you tackle the daunting issue of SCAM’s efficacy, you must find patients who happened to have recovered spectacularly well from a life-threatening disease after receiving your favourite form of SCAM. Once you have identified such a person, you detail her experience and publish this as a ‘case report’. It requires a little skill to brush over the fact that the patient also had lots of conventional treatments, or that her diagnosis was never properly verified. As a pseudo-scientist, you will have to learn how to discretely make such details vanish so that, in the final paper, they are no longer recognisable.

- Your boss might eventually point out that case reports are not really very conclusive. The antidote to this argument is simple: you do a large case series along the same lines. Here you can even show off your excellent statistical skills by calculating the statistical significance of the difference between the severity of the condition before the treatment and the one after it. As long as this reveals marked improvements, ignores all the many other factors involved in the outcome and concludes that these changes are the result of the treatment, all should be tickety-boo.

- Your boss might one day insist you conduct what he narrow-mindedly calls a ‘proper’ study; in other words, you might be forced to bite the bullet and learn how to do an RCT. As your particular SCAM is not really effective, this could lead to serious embarrassment in the form of a negative result, something that must be avoided at all costs. I, therefore, recommend you join for a few months a research group that has a proven track record in doing RCTs of utterly useless treatments without ever failing to conclude that it is highly effective. In other words, join a member of my ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME. They will teach you how to incorporate all the right design features into your study without the slightest risk of generating a negative result. A particularly popular solution is to conduct a ‘pragmatic’ trial that never fails to produce anything but cheerfully positive findings.

- But even the most cunningly designed study of your SCAM might one day deliver a negative result. In such a case, I recommend taking your data and running as many different statistical tests as you can find; chances are that one of them will produce something vaguely positive. If even this method fails (and it hardly ever does), you can always focus your paper on the fact that, in your study, not a single patient died. Who would be able to dispute that this is a positive outcome?

- Now that you have grown into an experienced pseudo-scientist who has published several misleading papers, you may want to publish irrefutable evidence of your SCAM. For this purpose run the same RCT over again, and again, and again. Eventually, you want a meta-analysis of all RCTs ever published (see examples here and here). As you are the only person who conducted studies on the SCAM in question, this should be quite easy: you pool the data of all your dodgy trials and, bob’s your uncle: a nice little summary of the totality of the data that shows beyond doubt that your SCAM works and is safe.