doctors

This paper notes that, according to the World Naturopathic Federation (WNF), the naturopathic profession is based on two fundamental philosophies of medicine (vitalism and holism) and seven principles of practice (healing power of nature; treat the whole person; treat the cause; first, do no harm; doctor as teacher; health promotion and disease prevention; and wellness). The philosophy, theory, and principles are translated to clinical practice through a range of therapeutic modalities. The WNF has identified seven core modalities: (1) clinical nutrition and diet modification/counselling; (2) applied nutrition (use of dietary supplements, traditional medicines, and natural health care products); (3) herbal medicine; (4) lifestyle counselling; (5) hydrotherapy; (6) homeopathy, including complex homeopathy; and (7) physical modalities (based on the treatment modalities taught and allowed in each jurisdiction, including yoga, naturopathic manipulation, and muscle release techniques).

The ‘scoping’ review was to summarize the current state of the research evidence for whole-system, multi-modality naturopathic medicine. Studies were included, if they met the following criteria:

- Controlled clinical trials, longitudinal cohort studies, observational trials, or case series involving five or more cases presented in any language

- Human studies

- Multi-modality treatment administered by a naturopath (naturopathic clinician, naturopathic physician) as an intervention

- Non-English language studies in which an English title and abstract provided sufficient information to determine effectiveness

- Case series in which five or more individual cases were pooled and authors provided a summative discussion of the cases in the context of naturopathic medicine

- All human research evaluating the effectiveness of naturopathic medicine, where two or more naturopathic modalities are delivered by naturopathic clinicians, were included in the review.

- Case studies of five or more cases were included.

Thirty-three published studies with a total of 9859 patients met inclusion criteria (11 US; 4 Canadian; 6 German; 7 Indian; 3 Australian; 1 UK; and 1 Japanese) across a range of mainly chronic clinical conditions. A majority of the included studies were observational cohort studies (12 prospective and 8 retrospective), with 11 clinical trials and 2 case series. The studies predominantly showed evidence for the efficacy of naturopathic medicine for the conditions and settings in which they were based. Overall, these studies show naturopathic treatment results in a clinically significant benefit for treatment of hypertension, reduction in metabolic syndrome parameters, and improved cardiac outcomes post-surgery.

The authors concluded that to date, research in whole-system, multi-modality naturopathic medicine shows that it is effective for treating cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal pain, type 2 diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, depression, anxiety, and a range of complex chronic conditions. Overall, these studies show naturopathic treatment results in a clinically significant benefit for treatment of hypertension, reduction in metabolic syndrome parameters, and improved cardiac outcomes post-surgery.

Where to start?

There are many issues here to choose from:

- The definition of naturopathy used in this review may be the one of the WHF, but it has little resemblance to the one used elsewhere. German naturopathic doctors, for instance, would not consider homeopathy to be a naturopathic treatment. They would also not, like the WNF does, subscribe to the long-obsolete humoral theory of disease. The only German professional organisation that is a member of the WNF is thus not one of naturopathic doctors but one of Heilpraktiker (the notorious German lay-practitioner created by the Nazis during the Third Reich).

- A review that includes observational studies and even case series, while drawing far-reaching conclusions on therapeutic effectiveness is, in my view, little more than embarrassing pseudo-science. Such studies are unable to differentiate between specific and non-specific therapeutic effects and therefore can tell us nothing about the effectiveness of a treatment.

- A review on a subject such as naturopathy (an approach which, after all, originated in Europe) that excludes studies not published in English (and without an English abstract providing sufficient information to determine effectiveness) is likely to be incomplete.

- The authors call their review a ‘scoping review’; they nevertheless draw conclusions not about the scope but the effectiveness of naturopathy.

- Many of the studies included in this review do, in fact, not comply with the inclusion criteria set by the review-authors.

- The review does not assess or even comment on the risks of naturopathic treatments.

- Several of the included studies are not investigations of naturopathy but of approaches that squarely fall under the umbrella of integrative or alternative medicine.

- Of the 33 studies included, only 5 were RCTs, and none of these was free of major limitations.

- None of the RCTs have been independently replicated.

- There is a remarkable absence of negative trials suggestion a strong influence of bias.

- The review lacks any trace of critical thinking.

- The authors are affiliated to institutions of naturopathy but declare no conflicts of interest.

- No funding source was named but it seems that it was supported by the WNF; their primary goal is to promote and advance the naturopathic profession.

- The review appeared in the notorious Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Prof Dwyer, the founding president of the Australian ‘Friends of Science in Medicine’, said the study damaged Southern Cross University’s reputation. “At the heart of this is the credibility of Southern Cross University,” he said. “There’s been a stand-off between SCU and the rest of the scientific community in Australia for a number of years and there have been challenges to whether they are really upholding the highest standards of evidence-based medicine.” Professor Dwyer also raised questions about the university’s credibility late last year when it accepted a $10 million donation from vitamin company Blackmore’s to establish a National Centre for Naturopathic Medicine.

My conclusion of naturopathy, as defined by the WNF, is that it is an obsolete form of quackery steeped in concepts of vitalism that should be abandoned sooner rather than later. And my conclusion about the new review agrees with Prof Dwyer’s judgement: it is an embarrassment to all concerned.

As you know, I have repeatedly written about integrative cancer therapy (ICT). Yet, to be honest, I was never entirely sure what it really is; it just did not make sense – not until I saw this announcement. It left little doubt about the nature of ICT.

As it is in German, allow me to translate it for you [the numbers added to the text refer to my comments below]:

ICT is a method of treatment that views humans holistically [1]. The approach is characterised by a synergistic application (integration) of all conventional [the actual term used is a derogatory term coined by Hahnemann to denounce the prevailing medicine of his time], immunological, biological and psychological insights [2]. In this spirit, also personal needs and subjective experiences of disease are accounted for [3]. The aim of this special approach is to offer cancer patients an individualised, interdisciplinary treatment [4].

Besides surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, ICT also includes hormone therapy, hyperthermia, pain management, immunotherapy, normalisation of metabolism, stabilisation of the psyche, physical activity, dietary changes, as well as substitution of vital nutrients [5].

With ICT, the newest discoveries of cancer research are being offered [6], that support the aims of ICT. Therefore, the aims of the ICT doctor include continuous research of the world literature on oncology [7]…

Likewise, one has to start immediately with measures that help prevent metastases and tumour progression [8]. Both the maximization of survival and the optimisation of quality of life ought to be guaranteed [9]. Therefore, the alleviation of the side-effects of the aggressive therapies are one of the most important aims of ICT [10]…

HERE IS THE GERMAN ORIGINAL

Die integrative Krebstherapie ist eine Behandlungsmethode, die den Menschen in seiner Ganzheit sieht und sich dafür einsetzt. Ihre Behandlungsweise ist gekennzeichnet durch die synergetische Anwendung (Integration) aller sinnvollen schulmedizinischen, immunologischen, biologischen und psychologischen Erkenntnisse. In diesem Sinne werden auch die persönlichen Bedürfnisse und die subjektiven Krankheitserlebnisse berücksichtigt. Ziel dieser besonderen Therapie ist es, dass dem Krebspatienten eine individuell eingerichtete und interdisziplinär geplante Behandlung angeboten wird.

Zur integrativen Krebstherapie gehört neben der operativen Tumorbeseitigung, Chemotherapie und Strahlentherapie auch die Hormontherapie, Hyperthermie, Schmerzbeseitigung, Immuntherapie, Normalisierung des Stoffwechsels, Stabilisierung der Psyche, körperliche Aktivierung, Umstellung der Ernährung sowie die Ergänzung fehlender lebensnotwendiger Vitalstoffe.

Mit dieser Behandlungsmethode werden auch die neuesten Entdeckungen der Krebsforschung angeboten, die die Ziele der Integrativen Krebstherapie unterstützen. Deshalb sind die ständigen Recherchen der umfangreichen Ergebnisse der Onkologie-Forschung in der medizinischen Weltliteratur auch Aufgabe der Mediziner in der Integrativen Krebstherapie…

Ebenso sollte auch sofort mit den Maßnahmen begonnen werden, die helfen, dieMetastasen Bildung und Tumorprogredienz zu verhindern. Nicht nur die Maximierung des Überlebens, sondern auch die Optimierung der Lebensqualität sollen gewährleistet werden. Deshalb ist auch die Linderung der Nebenwirkungen der aggressiven Behandlungsmethoden eines der wichtigsten Ziele der Integrativen Krebstherapie….

MY COMMENTS

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

- Actually, this describes conventional oncology!

ICT might sound fine to many consumers. I can imagine that it gives confidence to some patients. But it really is nothing other than the adoption of the principles of good conventional cancer care?

No!

But in this case, ICT is just a confidence trick!

It is a confidence trick that allows the trickster to smuggle no end of SCAM into routine cancer care!

Or did I miss something here?

Am I perhaps mistaken?

Please, do tell me!

The American Chiropractic Association (ACA) have just published new guidelines for chiropractors entitled ‘Guidelines for Disaster Service by Doctors of Chiropractic’. Let me show you a few short quotes from this remarkable document:

… Doctors of Chiropractic are uniquely qualified to serve in emergency situations in various capacities.

… their assessment and treatments can be performed in austere environments, on site or at staging areas providing rapid attention to the injury, accelerating healing and often decreasing or substituting the need for pharmaceutical intervention…

Through their education as primary care physicians, Doctors of Chiropractic have demonstrated competence in first aid and resuscitation skills and are able to assess, diagnose and triage so they may serve as first responders in the immediate care of victims at a disaster site…

During and after the disaster, the local Doctors of Chiropractic should interface with the state association and ACA to report on execution of action and outcome of the situation, make suggestions for response to future disasters and report any significant contacts made.

END OF QUOTES

Please allow me to make just 10 corrections and clarifications:

- Chiropractors are not medical doctors; to use the title in any medical context is misleading, to use it in the context of medical emergencies is quite simply reckless.

- Chiropractors are certainly not qualified to serve in emergency situations. This would require a totally different training, experience and set of skills.

- I am not aware of any good evidence that chiropractic can accelerate healing of any medical condition.

- I am also not aware that chiropractic might decrease or substitute the need for pharmaceutical interventions in emergency situations.

- Chiropractors are not primary care physicians.

- Chiropractors have not demonstrated competence in first aid and resuscitation skills.

- Chiropractors are not trained to diagnose the complex and often life-threatening conditions that occur in disaster situations.

- Chiropractors are not trained as first responders in disaster situations.

- Chiropractors are not qualified or trained to report on execution of action and outcome of disaster situation.

- Chiropractors are not qualified or trained to make suggestions for response to future disasters.

The new ACA guidelines are but a thinly disguised attempt to boost chiropractic. They have the potential to endanger lives. And they are an insult to those professionals who have trained hard to acquire the skills to respond to emergencies and disaster situations.

In other words, they are guidelines not for dealing with disasters, but for creating them.

The notion that ‘chiropractic adds years to your life’ is often touted, particularly of course by chiropractors (in case you doubt it, please do a quick google search). It is logical to assume that chiropractors themselves are the best informed about what they perceive as the health benefits of chiropractic care. Chiropractors would therefore be most likely to receive some level of this ‘life-prolonging’ chiropractic care on a long-term basis. If that is so, then chiropractors themselves should demonstrate longer life spans than the general population.

The notion that ‘chiropractic adds years to your life’ is often touted, particularly of course by chiropractors (in case you doubt it, please do a quick google search). It is logical to assume that chiropractors themselves are the best informed about what they perceive as the health benefits of chiropractic care. Chiropractors would therefore be most likely to receive some level of this ‘life-prolonging’ chiropractic care on a long-term basis. If that is so, then chiropractors themselves should demonstrate longer life spans than the general population.

Sounds logical?

Perhaps, but is the theory supported by evidence?

Back in 2004, a chiropractor, Lon Morgan, courageously tried to test the theory and published an interesting paper about it.

He used two separate data sources to examine the mortality rates of chiropractors. One source used obituary notices from past issues of Dynamic Chiropractic from 1990 to mid-2003. The second source used biographies from Who Was Who in Chiropractic – A Necrology covering a ten year period from 1969-1979. The two sources yielded a mean age at death for chiropractors of 73.4 and 74.2 years respectively. The mean ages at death of chiropractors is below the national average of 76.9 years; it also is below the average age at death of their medical doctor counterparts which, at the time, was 81.5.

So, one might be tempted to conclude that ‘chiropractic substracts years from your life’. I know, this would be not very scientific – but it would probably be more evidence-based than the marketing gimmick of so many chiropractors trying to promote their trade by saying: ‘chiropractic adds years to your life’!

In any case, Morgan, the author of the paper, concluded that this paper assumes chiropractors should, more than any other group, be able to demonstrate the health and longevity benefits of chiropractic care. The chiropractic mortality data presented in this study, while limited, do not support the notion that chiropractic care “Adds Years to Life …”, and it fact shows male chiropractors have shorter life spans than their medical doctor counterparts and even the general male population. Further study is recommended to discover what factors might contribute to lowered chiropractic longevity.

Another beautiful theory killed by an ugly fact!

The German Association of Medical Homeopaths (Deutscher Zentralverein homöopathischer Ärzte (DZVhÄ)) have recently published an article where, amongst other things, they lecture us about evidence-based medicine (EBM). If you feel that this might be a bit like an elephant teaching Fred Astaire how to step-dance, you could have a point. Here is their relevant paragraph:

… das Konzept der modernen Evidenzbasierte Medizin nach Sackett [stützt sich] auf drei Säulen: auf die klinischen Erfahrung der Ärzte, auf die Werte und Wünsche des Patienten und auf den aktuellen Stand der klinischen Forschung. Homöopathische Ärzte wehren sich gegen einen verengten Evidenzbegriff der Kritiker, der Evidenz allein auf die Säule der klinischen Forschung bzw. ausschließlich auf RCT verengen möchte und die anderen beiden Säulen ausblendet. Experten schätzen, dass bei einer solchen Auffassung von EbM rund 70 Prozent aller Leistungen der GKV nicht evidenzbasiert sei. Nötiger als eine Homöopathie-Debatte hat die deutsche Ärzteschaft aus unserer Sicht eine klare Verständigung darüber, welcher Evidenzbegriff nun gilt.

For those who cannot understand the full splendour of their argument because of the language problem, I translate as literally as I can:

… the concept of the modern EBM according to Sackett is based on three pillars: on the clinical experience of the doctors, on the values and wishes of the patient and on the current state of the clinical research. Homeopaths defend themselves against the narrowed understanding of ‘evidence’ of the critics which aims at narrowing evidence solely to the pillar of the clinical research or exclusively to RCT, while eliminating the other two pillars. Experts estimate that, with such an view of EBM, about 70% of all treatments reimbursed by our health insurances would not be evidence-based. We feel that we more urgently need a clear understanding which evidence definition applies than a debate about homeopathy.

END OF MY TRANSLATION

So, where is the hilarity in this?

I don’t know about you, but I find the following things worth a giggle:

- ‘narrowed understanding of evidence’ – this is a classical strawman; non-homeopaths tend to apply Sackett’s definition which states that ‘evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical experience with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research‘;

- as we see, Sackett’s definition is quite different from the one cited by the homeopaths;

- the three pillars cited by the homeopaths are those subsequently developed for Evidence Based Practice (EBP) and include: A) patient values, B) clinical expertise and C) external best evidence;

- as we see, these three pillars are also not quite the same as those suggested by the homeopaths;

- non-homeopaths do certainly not aim at eliminating the ‘other two pillars’;

- current best evidence clearly includes much more than just RCTs – to mention RCTs in this context therefore suggests that the ones guilty of narrowing anything might, in fact, be the homeopaths;

- even if it were true that 70% of reimbursable treatments are not evidence-based, this would hardly be a good reason to employ homeopathic remedies of which 100% are not even remotely evidence-based;

- unbeknown to the German homeopaths, the discussion about a valid definition of EBM has been intense, is as old as EBM itself, and would by now probably fill a mid-size library;

- this discussion does, however, in no way abolish the need to bring the debate about homeopathy to the only evidence-based conclusion possible, namely the discontinuation of reimbursement of this and all other bogus therapies.

In conclusion, I do thank the German homeopaths for being such regular contributors to fun and hilarity. I shall miss them, once they have fully understood EBM and are thus compelled to stop prescribing placebos.

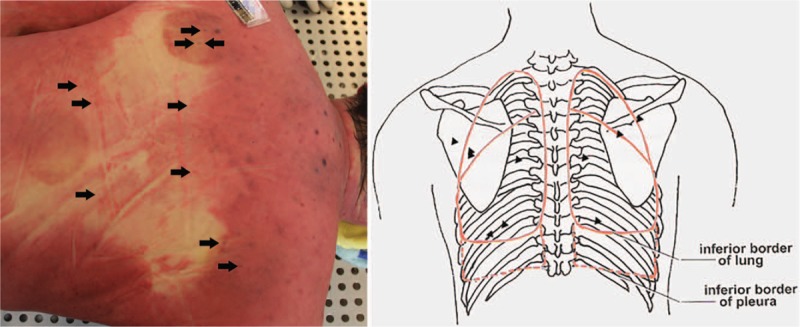

The most frequent of all potentially serious adverse events of acupuncture is pneumothorax. It happens when an acupuncture needle penetrates the lungs which subsequently deflate. The pulmonary collapse can be partial or complete as well as one or two sided. This new case-report shows just how serious a pneumothorax can be.

A 52-year-old man underwent acupuncture and cupping treatment at an illegal Chinese medicine clinic for neck and back discomfort. Multiple 0.25 mm × 75 mm needles were utilized and the acupuncture points were located in the middle and on both sides of the upper back and the middle of the lower back. He was admitted to hospital with severe dyspnoea about 30 hours later. On admission, the patient was lucid, was gasping, had apnoea and low respiratory murmur, accompanied by some wheeze in both sides of the lungs. Because of the respiratory difficulty, the patient could hardly speak. After primary physical examination, he was suspected of having a foreign body airway obstruction. Around 30 minutes after admission, the patient suddenly became unconscious and died despite attempts of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Whole-body post-mortem computed tomography of the victim revealed the collapse of the both lungs and mediastinal compression, which were also confirmed by autopsy. More than 20 pinprick injuries were found on the skin of the upper and lower back in which multiple pinpricks were located on the body surface projection of the lungs. The cause of death was determined as acute respiratory and circulatory failure due to acupuncture-induced bilateral tension pneumothorax.

The authors caution that acupuncture-induced tension pneumothorax is rare and should be recognized by forensic pathologists. Postmortem computed tomography can be used to detect and accurately evaluate the severity of pneumothorax before autopsy and can play a supporting role in determining the cause of death.

The authors mention that pneumothorax is the most frequent but by no means the only serious complication of acupuncture. Other adverse events include:

- central nervous system injury,

- infection,

- epidural haematoma,

- subarachnoid haemorrhage,

- cardiac tamponade,

- gallbladder perforation,

- hepatitis.

No other possible lung diseases that may lead to bilateral spontaneous pneumothorax were found. The needles used in the case left tiny perforations in the victim’s lungs. A small amount of air continued to slowly enter the chest cavities over a long period. The victim possibly tolerated the mild discomfort and did not pay attention when early symptoms appeared. It took 30 hours to develop into symptoms of a severe pneumothorax, and then the victim was sent to the hospital. There he was misdiagnosed, not adequately treated and thus died. I applaud the authors for nevertheless publishing this case-report.

This case occurred in China. Acupuncturists might argue that such things would not happen in Western countries where acupuncturists are fully trained and aware of the danger. They would be mistaken – and alarmingly, there is no surveillance system that could tell us how often serious complications occur.

The inventor of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, was a German physician. It is therefore not surprising that homeopathy quickly took hold in Germany. After its initial success, homeopathy’s history turned out to be a bit of a roller coaster. But only recently, a vocal and effective opposition has come to the fore (see my previous post).

Despite the increasing opposition, the advent of EBM, and the much-publicised fact that the best evidence fails to show homeopathy’s effectiveness, there are many doctors who still practice it. According to one website, there are 4330 doctor homeopaths in Germany (plus, of course, almost the same number of Heilpraktiker who also use homeopathy). This figure is, however, out-dated. The German Medical Association told a friend that, at the end of 2017, there were 5612 doctors practising in Germany who hold the additional qualification (‘Zusatz-Weiterbildung’) homeopathy.

That’s a lot, I find.

Why so many?

Whenever I give lectures on the subject, this is the question that comes up with unfailing regularity. Many people who ask would also imply that, if so many doctors use it, homeopathy must be fine, because doctors have studied and know what they are doing.

My answer usually is that the phenomenon is due to many factors:

- history,

- regulation,

- misinformation,

- powerful lobby groups,

- patient demand,

- homeopathy’s image of being gentle, safe and holistic,

- patients’ need to believe in something more than ‘just science’,

- the fact that most German health insurances reimburse it,

- political support,

- etc.

But, in fact, the true explanation, as I have learnt recently, might be much simpler and more profane: MONEY!

A German GP gets 4.36 Euros for taking a conventional history.

If he is a homeopath taking an initial homeopathic history, (s)he gets 130 € according to the ‘Selektivvertrag’.

So, yes, doctors have studied and know that the difference between the two amounts is significant.

In the latest issue of ‘Simile’ (the Faculty of Homeopathy‘s newsletter), the following short article with the above title has been published. I took the liberty of copying it for you:

Members of the Faculty of Homeopathy practising in the UK have the opportunity to take part in a trial of a new homeopathic remedy for treating infant colic. An American manufacturer of homeopathic remedies has made a registration application for the new remedy to the MHRA (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency) under the UK “National Rules” scheme. As part of its application the manufacturer is seeking at least two homeopathic doctors who would be willing to trial the product for about a year, then write a short report about using the remedy and its clinical results. If you would like to take part in the trial, further details can be obtained from …

END OF QUOTE

A homeopathic remedy for infant colic?

Yes, indeed!

The British Homeopathic Association and many similar ‘professional’ organisations recommend homeopathy for infant colic: Infantile colic is a common problem in babies, especially up to around sixteen weeks of age. It is characterised by incessant crying, often inconsolable, usually in the evenings and often through the night. Having excluded underlying pathology, the standard advice given by GPs and health visitors is winding technique, Infacol or Gripe Water. These measures are often ineffective but fortunately there are a number of homeopathic medicines that may be effective. In my experience Colocynth is the most successful; alternatives are Carbo Veg, Chamomilla and Nux vomica.

SO, IT MUST BE GOOD!

But hold on, I cannot find a single clinical trial to suggest that homeopathy is effective for infant colic.

Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh, I see, that’s why they now want to conduct a trial!

They want to do the right thing and do some science to see whether their claims are supported by evidence.

How very laudable!

After all, the members of the Faculty of Homeopathy are doctors; they have certain ethical standards!

After all, the Faculty of Homeopathy aims to provide a high level of service to members and members of the public at all times.

Judging from the short text about the ‘homeopathy for infant colic trial’, it will involve a few (at least two) homeopaths prescribing the homeopathic remedy to patients and then writing a report. These reports will unanimously state that, after the remedy had been administered, the symptoms improved considerably. (I know this because they always do improve – with or without treatment.)

These reports will then be put together – perhaps we should call this a meta-analysis? – and the overall finding will be nice, positive and helpful for the American company.

And now, we all understand what homeopaths, more precisely the Faculty of Homeopathy, consider to be evidence.

The Clinic for Complementary Medicine and Diet in Oncology was opened, in collaboration with the oncology department, at the Hospital of Lucca (Italy) in 2013. It uses a range of alternative therapies aimed at reducing the adverse effects of conventional oncology treatments.

Their latest paper presents the results of complementary medicine (CM) treatment targeted toward reducing the adverse effects of anticancer therapy and cancer symptoms, and improving patient quality of life. Dietary advice was aimed at the reduction of foods that promote inflammation in favour of those with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

This is a retrospective observational study on 357 patients consecutively visited from September 2013 to December 2017. The intensity of symptoms was evaluated according to a grading system from G0 (absent) to G1 (slight), G2 (moderate), and G3 (strong). The severity of radiodermatitis was evaluated with the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) scale. Almost all the patients (91.6%) were receiving or had just finished some form of conventional anticancer therapy.

The main types of cancer were breast (57.1%), colon (7.3%), lung (5.0%), ovary (3.9%), stomach (2.5%), prostate (2.2%), and uterus (2.5%). Comparison of clinical conditions before and after treatment showed a significant amelioration of all symptoms evaluated: nausea, insomnia, depression, anxiety, fatigue, mucositis, hot flashes, joint pain, dysgeusia, neuropathy.

The authors concluded that the integration of evidence-based complementary treatments seems to provide an effective response to cancer patients’ demand for a reduction of the adverse effects of anticancer treatments and the symptoms of cancer itself, thus improving patient’s quality of life and combining safety and equity of access within public healthcare systems. It is, therefore, necessary for physicians (primarily oncologists) and other healthcare professionals in this field to be appropriately informed about the potential benefits of CMs.

Why do I call this ‘wishful thinking’?

I have several reasons:

- A retrospective observational study cannot establish cause and effect. It is likely that the findings were due to a range of factors unrelated to the interventions used, including time, extra attention, placebo, social desirability, etc.

- Some of the treatments in the therapeutic package were not CM, reasonable and evidence-based. Therefore, it is likely that these interventions had positive effects, while CM might have been totally useless.

- To claim that the integration of evidence-based complementary treatments seems to provide an effective response to cancer patients’ is pure fantasy. Firstly, some of the CMs were certainly not evidence-based (the clinic’s prime focus is on homeopathy). Secondly, as already pointed out, the study does not establish cause and effect.

- The notion that it is necessary for physicians (primarily oncologists) and other healthcare professionals in this field to be appropriately informed about the potential benefits of CMs is not what follows from the data. The paper shows, however, that the authors of this study are in need to be appropriately informed about EBM as well as CM.

I stumbled across this paper because a homeopath cited it on Twitter claiming that it proves the effectiveness of homeopathy for cancer patients. This fact highlights why such publications are not just annoyingly useless but acutely dangerous. They mislead many cancer patients to opt for bogus treatments. In turn, this demonstrates why it is important to counterbalance such misinformation, critically evaluate it and minimise the risk of patients getting harmed.

Twenty years ago (5 years into my post at Exeter), I published this little article (BJGP, Sept 1998). It was meant as a sort of warning – sadly, as far as I can see, it has not been heeded. Oddly, the article is unavailable on Medline, I therefore take the liberty of re-publishing it here without alterations (if I had to re-write it today, I would not change much) or comment:

Once the omnipotent heroes in white, physicians today are at risk of losing the trust of their patients. Medicine, some would say, is in a deep crisis. Shouldn’t we start to worry?

The patient-doctor relationship, it seems, is at the heart of this argument. Many patients are deeply dissatisfied with this aspect of medicine. A recent survey on patients consulting GPs and complementary practitioners in parallel and for the same problem suggested that most patients are markedly more happy with all facets of the therapeutic encounter as offered by complementary practitioners. This could explain the extraordinary rise of complementary medicine during recent years. The neglect of the doctor-patient relationship might be the gap in which complementary treatments build their nest.

Poor relationships could be due to poor communication. Many books have been written about communications skills with patients. But never mind the theory, the practice of all this may be less optimal than we care to believe. Much of this may simply relate to the usage of language. Common terms such as ‘stomach’, ‘palpitations’, ‘lungs’, for instance, are interpreted in different ways by lay and professional people. Words like ‘anxiety’, ‘depression’, and ‘irritability’ are well defined for doctors, while patients view them as more or less interchangeable. At a deeper level, communication also relates to concepts and meanings of disease and illness. For instance, the belief that a ‘blockage of the bowel’ or an ‘imbalance of life forces’ lead to disease is as prevalent with patients as it is alien to doctors. Even on the most obvious level of interaction with patients, physicians tend to fail. Doctors often express themselves unclearly about the nature, aim or treatment schedule of their prescriptions.

Patients want to be understood as whole persons. Yet modern medicine is often seen as emphazising a reductionistic and mechanistic approach, merely treating a symptom or replacing a faulty part, or treating a ‘case’ rather than an individual. In the view of some, modern medicine has become an industrial behemoth shifted from attending the sick to guarding the economic bottom line, putting itself on a collision course with personal doctoring. This has created a deeply felt need which complementary medicine is all too ready to fill. Those who claim to know the reason for a particular complaint (and therefore its ultimate cure) will succeed in satisfying this need. Modern medicine has identified the causes of many diseases while complementary medicine has promoted simplistic (and often wrong) ideas about the genesis of health and disease. The seductive message usually is as follows: treating an illness allopathically is not enough, the disease will simply re-appear in a different guise at a later stage. One has to tackle the question – why the patient has fallen ill in the first place. Cutting off the dry leaves of a plant dying of desiccation won’t help. Only attending the source of the problem, in the way complementary medicine does, by pouring water on to the suffering plant, will secure a cure. This logic is obviously lop-sided and misleading, but it creates trust because it is seen as holistic, it can be understood by even the simplest of minds, and it generates a meaning for the patient’s otherwise meaningless suffering.

Doctors, it is said, treat diseases but patients suffer from illnesses. Disease is something an organ has; illness is something an individual has. An illness has more dimensions than disease. Modern medicine has developed a clear emphasis on the physical side of disease but tends to underrate aspects like the patient’s personality, beliefs and socioeconomic environment. The body/mind dualism is (often unfairly) seen as a doctrine of mainstream medicine. Trust, it seems, will be given to those who adopt a more ‘holistic’ approach without dissecting the body from the mind and spirit.

Empathy is a much neglected aspect in today’s medicine. While it has become less and less important to doctors, it has grown more and more relevant to patients. The literature on empathy is written predominantly by nurses and psychologists. Is the medical profession about to delegate empathy to others? Does modern, scientific medicine lead us to neglect the empathic attitude towards our patients? Many of us are not even sure what empathy means and confuse empathy with sympathy. Sympathy with the patient can be described as a feeling of ‘I want to help you’. Empathy, on these terms, means ‘I am (or could be) you’; it is therefore some sort of an emotional resonance. Empathy has remained somewhat of a white spot on the map of medical science. We should investigate it properly. Re-integrating empathy into our daily practice can be taught and learned. This might help our patients as well as us.

Lack of time is another important cause for patients’ (and doctors’) dissatisfaction. Most patients think that their doctor does not have enough time for them. They also know from experience that complementary medicine offers more time. Consultations with complementary practitioners are appreciated, not least because they may spend one hour or so with each patient. Obviously, in mainstream medicine, we cannot create more time where there is none. But we could at least give our patients the feeling that, during the little time available, we give them all the attention they require.

Other reasons for patients’ frustration lie in the nature of modern medicine and biomedical research. Patients want certainty but statistics provides probabilities at best. Some patients may be irritated to hear of a 70% chance that a given treatment will work; or they feel uncomfortable with the notion that their cholesterol level is associated with a 60% chance of suffering a heart attack within the next decade. Many patients long for reassurance that they will be helped in their suffering. It may be ‘politically correct’ to present patients with probability frequencies of adverse effects and numbers needed to treat, but anybody who (rightly or wrongly) promises certainty will create trust and have a following.

Many patients have become wary of the fact that ‘therapy’ has become synonymous with ‘pharmacotherapy’ and that many drugs are associated with severe adverse reactions. The hope of being treated with ‘side-effect-free’ remedies is a prime motivator for turning to complementary medicine.

Complementary treatments are by no means devoid of adverse reactions, but this fact is rarely reported and therefore largely unknown to patients. Physicians are regularly attacked for being in league with the pharmaceutical industry and the establishment in general. Power and money are said to be gained at the expense of the patient’s well-being. The system almost seems to invite dishonesty. The ‘conspiracy theory’ goes as far as claiming that ‘scientific medicine is destructive, extremely costly and solves nothing. Beware of the octopus’. Spectacular cases could be cited which apparently support it. Orthodox medicine is described as trying to ‘inhibit the development of unorthodox medicine’, in order to enhance its own ‘power, status and income’. Salvation, it is claimed, comes from the alternative movement which represents ‘… the most effective assault yet on scientific biomedicine’. Whether any of this is true or not, it is perceived as the truth by many patients and amounts to a serious criticism of what is happening in mainstream medicine today.

In view of such criticism, strategies for overcoming problems and rectifying misrepresentations are necessary. Mainstream medicine might consider discovering how patients view the origin, significance, and prognosis of the disease. Furthermore, measures should be considered to improve communication with patients. A diagnosis and its treatment have to make sense to the patient as much as to the doctor – if only to enhance adherence to therapy. Both disease and illness must be understood in their socio-economic context. Important decisions, e.g. about treatments, must be based on a consensus between the patient and the doctor. Scientists must get better in promoting their own messages, which could easily be far more attractive, seductive, and convincing than those of pseudo-science.These goals are by no means easy to reach. But if we don’t try, trust and adherence will inevitably deteriorate further. I submit that today’s unprecedented popularity of complementary medicine reflects a poignant criticism of many aspects of modern medicine. We should take it seriously